7,70 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Modern History Press

- Kategorie: Bildung

- Sprache: Englisch

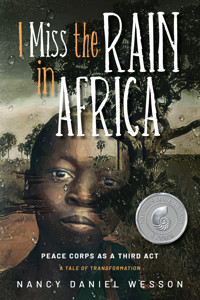

At a time when her friends were planning cushy retirements, Nancy Wesson instead walked away from a comfortable life and business to head out as a Peace Corps Volunteer in post-war Northern Uganda. She embraced wholeheartedly the grand adventure of living in a radically different culture, while turning old skills into wisdom. Returning home becomes a surreal experience in trying to reconcile a life that no longer "fits." This becomes the catalyst for new revelations about family wounds, mystical experiences, and personal foibles.

Nancy shows us the power of stepping into the void to reconfigure life and enter the wilderness of the uncharted territory of our own memories and psyche, to mine the gems hidden therein. Funny, heartbreaking, insightful and tender, I Miss the Rain in Africa is the story of honoring the self, discovering a new lens through which to view life, and finding joy along the path.

"Inspiring and educational when it comes to what we can accomplish when we put our best foot forward, I Miss the Rain in Africa shows how Nancy Daniel Wesson and others are putting the needs of others ahead of themselves-and what we can all do when it comes to stepping out on faith and choosing to act."

-- Cyrus Webb, media personality and author, Conversations Magazine

"I would think that many of us could learn or strive to live life to the fullest by following Nancy's example. Imagine venturing into new realms-especially at a later time in life when we possess meaningful knowledge for analyzing, but also for applying a critical philosophical perspective on new experiences."

--Gary Vizzo, former management & operations director, Peace Corps Community Development: African and Asia

"I Miss the Rain in Africa is an absorbing record of the exploration of self by a woman who, at age 64, enters a remote area of Africa to work with an NGO. Part adventure, part interior monologue, this is an account of a 21st century derring-do by an intrepid, intriguing and always optimistic woman who will, undoubtedly, enjoy a fourth and maybe even a fifth act wherever she may find herself."

--Eileen Purcell, outreach literacy coordinator, Clatsop Community College, Astoria, Oregon

"Wesson offers a montage of stories and experiences that introduces the reader to the colorful people and challenging life in Uganda. Wesson's observations are shared with humor, respect, and compassion. For anyone who has ever wondered what serving in Peace Corps or immersing oneself in a radically different life overseas might be like, this book provides a portal."

--Kathleen Willis, Retired Peace Corps Volunteer-Community Organizer, former organizational development consultant

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 469

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

I Miss the Rain in Africa: Peace Corps as a Third Act

Copyright © 2021 by Nancy Daniel Wesson. All Rights Reserved.

ISBN 978-1-61599-574-5 paperback

ISBN 978-1-61599-575-2 hardcover

ISBN 978-1-61599-576-9 eBook

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Wesson, Nancy Daniel, 1947- author.

Title: I miss the rain in Africa : Peace Corps as a third act / Nancy Daniel Wesson.

Description: Ann Arbor, MI : Modern History Press, 2021. | Includes index. | Summary: "Wesson details her Peace Corps tour of duty as a senior in a remote corner of Uganda starting in 2011. This retrospective, supplemented by blog posts she made in country, is a comprehensive diary of her personal experiences working with a literacy NGO and how it shaped her life after returning to the USA"-- Provided by publisher.

Identifiers: LCCN 2021014909 (print) | LCCN 2021014910 (ebook) | ISBN 9781615995745 (paperback) | ISBN 9781615995752 (hardcover) | ISBN 9781615995769 (pdf) | ISBN 9781615995769 (epub)

Subjects: LCSH: Wesson, Nancy Daniel, 1947- | Peace Corps (U.S.)--Uganda. | Volunteer workers in social service--Uganda--Biography. | Americans--Uganda--Biography. | Uganda--History--1979-

Classification: LCC DT433.287 .W47 2021 (print) | LCC DT433.287 (ebook) | DDC 966.61044092--dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021014909

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021014910

Published by

Modern History Press

www.ModernHistoryPress.com

5145 Pontiac Trail

Ann Arbor, MI 48105

Tollfree 888-761-6268

Fax 734-417-4266

Distributed by: Ingram (USA/CAN/AU), Bertram’s Books (UK/EU)

Contents

Uganda Map

Foreword

How It Started

Part One - Muzungu: Foreigner

1 Welcome to Hell

2 WHY: What I knew then

3 Fixin’ to get Ready

4 Boot Camp: You’re in the Army Peace Corps Now

5 HomeStay

6 Pinky, the Teflon Dog

7 Haircuts and Chocolate

8 Gulu Town

9 The Light at the End of Tunnel

Part Two – It Begins

10 Getting to Site

11 Shut Up and Listen

12 New Digs

13 Rain

14 The Quest

15 You Have Been Lost

16 The Teakettle

17 Emotional Rollercoaster

18 Screams

19 A Day in the Life of a Bus

20 The Way Things Are Done

21 Dry Season, Lizards and FIRE

22 Gulu Loves Dolly Parton and The Man in Blue

23 What Fresh Hell Is This?

24 A Loko Leb Acholi ma Nok Nok

25 The Six-Month Trough

26 The United Nations Comes to Town

27 Critters

28 But What Are You Doing There?

Part Three - Settling In

29 Eleven Months in Country: Sober Thoughts

30 Going and Coming: It Came from Where?

31 Peace Camp

32 And Then There Was Ebola

33 Sometimes it Works, Sometimes it Doesn’t

34 Fits and Starts

35 Looking Back at Mid-service

36 Pillowcase Dresses: Literacy in a New Light

37 Ugly Americans?

Part Four The Final Stretch

38 Peter

39 A Library for Children

40 Hearing Aids Déjà Vu

41 Tragedy Strikes

42 Texas in the Rearview Mirror

43 We’ve Been Sleeping Around

44 Keeping Girls in School

45 The Broken Digit

46 Fixin’ to Get Ready

47 A Parallel Universe

Part Five ~ Intermission

48 Reassembling

49 Where Is Home?

50 Jigsaw Puzzle

51 No Going Home

Part Six ~ Answers

52 The Thing That Started It All

53 Casting About

54 Heartbeat

55 Another Cottage

56 Rescripting History

57 Lessons from my Mother

58 Gifts my Father Gave Me

59 The Alchemy of Shift

60 What If…

Apwoyo Matek: Thank You

A Brief History of Northern Uganda: The Horrors of War

About the Author

Glossary

Index

See also:A Brief History of Northern Uganda starting on p. 258

Foreword

I Miss the Rain in Africa: Peace Corps as a Third Act, is an absorbing record of a woman’s literacy work in Northern Uganda. It is also a record of the exploration of self, explored by a woman who enters a remote area of Africa at age 64 to work with a Non-Governmental Organization (NGO). Ugandans were emerging from Joseph Kony’s cruel and bizarre rebel insurgency which had left the Acholi populace brutalized and mired in poverty. Assigned to an outpost in the north of Uganda, “where all bus trips begin with a prayer” and “bathroom breaks can be hazardous to health,” Nancy Wesson begins to live and work with survivors and strivers.

Western privilege and pride in institutional roadmaps to progress have no place here. Daily life for Ugandans is a struggle unimaginable even to the poorest Americans. Life is indeed precarious in Gulu, yet education is highly valued, and solutions hammered out of almost nothing. Season and weather guide life here and everything is “about the relationship, not the clock.” Westerners used to direct and quick solutions must adjust quickly to decisions made through consensus.

But serendipity lives in Africa, too. Nancy gets to know her landlady’s son which leads to literacy materials made of jigsaw puzzles. The residents of Gulu leave a deep imprint on the author; in particular, Peter, whose education she sponsors. On trips to the bush, exhausting and hazardous, Nancy works with teachers to carve out learning spaces. Her work in Uganda would leave her a bit battered and re-entry to the States—shell shocked at the contrasts. “Recalibration” is sought and achieved through another exploratory journey into the maturing self, requiring a reckoning with remembrance, recognition and reconciliation.

With self-deprecating humor, curiosity in all things, and empathy for all, Nancy takes us through an account of acclimation, acceptance, and peace with all the different geographies she encounters—physical, communal, spiritual. “I had devised a portable life with total autonomy and it was daunting. Having infinite possibilities was both the good news and the bad news.” Living in Uganda brought home the knowledge that having choices is the ultimate luxury, to be made “wisely and often.”

Part adventure, part interior monologue, I Miss the Rain in Africa: Peace Corps as a Third Act is an account of 21st century derring-do by an intrepid, intriguing, and always optimistic woman who will undoubtedly enjoy a fourth and maybe even a fifth act wherever she may find herself.

Eileen Purcell, Outreach Literacy Coordinator Clatsop Community College, Astoria, Oregon

How It Started

Curiously, this is not precisely the book I thought I would be writing when I started. It began as the tale of the grand adventure of a sixty-four-year-old white woman (that would be me) in Peace Corps, Uganda, and the reinvention of self that followed. And it certainly is that…

But as I wrote, the story became so much bigger, as one shift in self introduced another—and then another—and another. Leaving it all behind for Peace Corps set in motion a personal transformation that evolved even as I wrote; in fact, the writing itself became a catalyst for transcending life events I thought were hard-wired in my psyche. No one was more shocked than I.

It started when I walked away from a largely successful career and lifestyle that were no longer serving me and stepped into the void—off a virtual cliff, some would say. I was operating on instincts that had never failed me, and trusting that the tools I had at my disposal would serve as a parachute.

Friends called it brave, others called it misguided, but it felt like neither of those. It was simply the next step in what has been an interesting life.

It’s been six years since I returned from Uganda, and it’s taken every bit of that time to understand the multiple layers of insights, gifts and life changes set in motion by that quest. Though the revelations are still unfolding and reshaping a new life, I am often asked what I got from that experience. While I am hard pressed to condense it, I would say I left needing to break free of the gravitational pull that was keeping me in a constrained orbit, andreturned with a new appreciation of who I am, how I can contribute, and the total freedom to reconfigure the life that is still unfolding.

Although I didn’t anticipate it at the time, Peace Corps stripped the veneer I’d accumulated over the years to accommodate jobs, husbands and kids—allowing innate abilities to blossom, masked fears to be reconciled, and profound wounds to be healed, representing nothing short of a total paradigm shift.

I have unearthed a heartfelt appreciation of my past. I had discounted its influence, but it is what helped me to both endure Peace Corps’ hardships, and to mine the experiences for the gems it had to offer.

In the tale that follows, rain is a character in its own right, because of the way it inserted itself into every single aspect of life, emotion, and intellect, and the defining role it played in my unfolding. I still miss the rains in Africa.

Every Peace Corps story is unique and what one chooses to make of it, and while it may have a discreet starting point, the experience never really ends. My personal experiences elicited a depth of compassion, forgiveness, and an ability to be present that had previously eluded me, but have become constant companions in returning home.

In an effort to keep true to the progression of attitudes and emotions, much of what follows is taken either verbatim from or is an extrapolation of my private journal entries or the public blog, (ATexanGoesQuesting.blogspot.com) and are so noted. Other musings are purely mine and reflect the deeper lessons and emotions as I grew through the process.

Re-reading some of the entries is painful in the review of my judgments/feelings at the time. I ask forgiveness for those. I’ve purposely not edited these out, not because I think they are justified, but because they are honest representations of the often ugly difficulty of adjusting to new circumstances, coming from a life of relative privilege we enjoy as Americans. This very discomfort was part of my coming to terms with my own attitudes, blind-spots, and embedded attitudes that needed revealing before they could be acknowledged and examined. I pray you will not judge me too harshly.

I hope you enjoy the adventure.

Part One -

Muzungu: Foreigner

1

Welcome to Hell

We’re pouring off the bus at midnight—black-as-the-inside-of-a-cat, into the first of many rains, ankle deep mud and a buzzing fog of mosquitoes invading every orifice of forty-six disgruntled, sleep deprived, starving trainees. We grope for anything familiar—luggage perhaps—but there is only chaos. “Oh God, what have I done! Please don’t let this be real.” But it is.

In the dark, I identify my luggage and separate it from ninety-some-odd other overloaded bags vomited forth from two buses into the slop under a huge tree. Rollers on my carefully chosen bags are useless in this mud and uneven ground strewn with random stepping stones, disjointed walkways, puddles, rocks and grumbling humanity. That tree later proved to be a mango tree. Little did I know that I’d be spending much of the next two-plus years under them.

Weary voices float through the miasma of mosquitoes getting their quart of blood: “Where do we go?” “I need to pee!” “I’m hungry!” Is anyone listening out there?

Someone grabs my bag out of the mud. “My name is Gary. Can I help you with those?”

“Oh God yes! Please!”

He’s smiling and looks calm—obviously not one of us. I plough through the obstacle course of human misery and the mosquito-gauze against my face and finally arrive at the door to a huge room dismally lit by one bare light bulb dangling from a cord. I’m aghast at what I see: wall-to-wall bunk beds and luggage piled so deep no one else can get in without mountaineering equipment. “One bathroom for all these women!” says a panicked voice I can’t pair with a name; we’ve only recently met our other volunteers. Still, I can tell it’s one of us by the tone-ragged desperation.

My mind is reeling with a mini life-review. This can’t be happening! I left a perfectly nice life for THIS! I am definitely not in Texas anymore, and where are Dorothy’s red shoes when I need them? God, I wish I could click my heels and be out of here. Gary motions us toward another cabin and we slog over to a small, round hut with only four bunk beds. I land on the one closest to the bathroom and collapse.

Really? Is this what I was so excited about? Oh shit, is this what we had to change into our “professional” clothes for before even landing? After 18 hours of flight? Before departing, we were told there would be a dinner in honor of our arrival, so we abandon our luggage and thread our way to the main hall filled with long tables—two in the front loaded with WHAT! Stale bread, peanut butter and jelly, with tea to drink turns out to be “dinner.” Oh, this just gets better and better.

The evening comes to an end at around 1:00 AM after a truly forgettable welcome speech. After another hour of finding toothbrush and pajamas, jockeying with seven other women for bathroom privileges and repacking luggage to stash it under the bed, I collapse into bed, tuck in the mosquito net and consider the truly ignominious end to an already exhausting day. I congratulate myself for packing earplugs as the room fills with the sonorous buzz of snoring. I ponder the fact that a cold water trickle-shower and discomfort are foreshadowing things to come. I’m angry, exhausted, and forlorn, but no time for that; hurry up and sleep. Training starts at 8:00 AM and breakfast is offered at 7. Be prompt.

In the words of Dorothy Parker, “What fresh hell is this?”

WELCOME TO PEACE CORPS UGANDA!

Journal: Three Days Ago in Austin

Bleary eyed, nervous and with a lump in my throat, I left Austin after staying up most of the night to be sure neither my business website, Focus On Space, nor my book site, Moving Your Aging Parents, would expire in my absence. Updating contact information so my friend could handle things for a couple of years was the closest I could come to hanging on to any vestiges of what was fast becoming my former life. It was too late for soul-searching.

On our way to the airport, we had to stop and have a Power of Attorney (POA) notarized before I could leave on a morning flight getting me to Philadelphia for a fast and furious introduction to Peace Corps. This final chaos after months of preparation would characterize much of the next ten weeks. The first hurdle was luggage: two 40-pound bags packed to the bursting-point with the paraphernalia for living in the land-that-time-forgot for twenty-seven months. Packed and repacked, I prayed for the first time in my diet-conscious life that my Weight-Watchers scales were right and that I wouldn’t have to jettison anything.

That hurdle passed, I sat and waited—guarding my carry-on filled with life-line items: pictures of my sons, a computer I didn’t know if I would ever be able to use, camera, solar chargers, infra-red water purifier, and six months of any prescription meds I would require until PC supplies clicked in—in short, the things I knew I wouldn’t be able to find in Uganda. Taking deep breaths as I boarded the plane, the reality of what I was about to do began to sink in.

I. AM. LEAVING. EVERYTHING. BEHIND.

In Philly, I checked in, found the impromptu lounge and watched as the other forty-four new recruits straggled in, in different states of fear, excitement and fatigue. Most were young. I wondered, at 64 will I be the oldest? In an assembly line, we signed documents, got our ID packets and walk-around money and were introduced to our first taste of Peace Corps. It was not the welcoming introduction I was hoping for and it took a long time for it to improve.

Already feeling a little undone by the prospect of being out of contact with my previously known life, family and friends for the next two-plus years, what I knew about Uganda didn’t put me at ease. The infamous ruler, Idi Amin, the most notorious in a list of Uganda’s barbaric dictators and immortalized in The Last King of Scotland, was the underpinning of my sense of the country. Somehow, Winston Churchill’s calling Uganda, The Pearl of Africa, provided little solace.

In that frame of mind, I took it as a positive sign when I discovered I’d be sharing a room with the adorable Susie, a perky, twenty-something volunteer from Portland. In my need to find some good omens, I latched onto this one because one of my sons was living near Portland. The next morning started with paperwork, introductions and what would be the first of too many icebreaker games, prodding us into the Peace Corps frame of mind.

Having done years of training in other domains, I groaned. Feeling like I’d landed in a parallel universe between grade school and junior high, I hoped this would get better. It didn’t. It was just a precursor to training in Uganda and a parade of activities I’d left behind decades ago. I’d need some personal attitude adjustment, because I’d leased my house, closed my business, and had a fine going-away party.

The phrase, “Doesn’t play well with others,” came to mind. Crap! Have I become that person?

Simply put, it was time to let go of control and embrace the adventure.

Journal: August 2, Philadelphia

Training in earnest began. I was nearly giddy when I spotted a few gray hairs and wrinkles in the mix and realized roughly a third of our group was age fifty-plus, although the average age of a Peace Corps volunteer hovers around twenty-eight. We were six single women, a couple of single men and the rest, couples. Representing an incredible mix of talent and credentials, we were authors, CEOs, CPAs, professors, activists, speakers, counselors, nurses and entrepreneurs. As children-of-the-sixties, we were vocal, irrepressible, autonomous rule-breakers by nature. The relief was palpable as we identified each other, but bonding wouldn’t take place until much later and would ultimately play a role in revamping Peace Corps training.

For all of us, the decision to step out of our regular lives, careers, businesses and families became more real when we were issued our Peace Corps Passports and Uganda Visas.

That night was spent making a last minute telephone call to Brett, my son still in-country—wishing I could also reach his brother, Travis, in Germany—and sending out a group message, my last email from the US. Not knowing when—or IF I would have access to a charged computer, much less Internet, for the next two years, I was already homesick—a malady I hoped wouldn’t flatten me in Uganda. Although an early Close-of-Service (COS) is always an option, it wasn’t one I would ever consider. I’d already sent out my final So-Long-Farewell-Auf-Wiedersehen-Good-Bye newsletter to the hundreds of clients and friends gathered over a lifetime and 15 years of consulting in Texas, Washington, D.C. and New Zealand.

I waskissing my identity goodbye, kind of likewitness-protection, but without the crime.

Journal: August 3, Philadelphia

Afloat in a sea of emotions, each of us schlepping one carry-on filled with coveted electronics, meds, and enough entertainment to get us through 18 hours of flight, our herd was corralled onto buses that would ferry us to JFK Airport where we would get to flash our new passports. Propelled forward on a flood of adrenaline, we individually and collectively wondered if we would get through luggage check unscathed. We were already dreading the mandate to change into professional clothes in the airplane bathroom, prior to our midnight arrival in Entebbe.

I was mentally hoping I’d not forgotten some essential details about the house I’d left with new tenants and hoping nothing would happen to threaten the owner-finance loan that would come-due in a year. I’m sure I wasn’t alone in this last minute emotional turmoil. The collective holding-of-breath was palpable.

Journal: August 4, Arrival in Uganda

Arrival at Entebbe—for those old enough to remember the 1977 Raid on Entebbe by Israeli troops in response to a hijacking orchestrated by Idi Amin—brought on a frisson of anticipation. Combined with the knowledge that northern Uganda was just pulling out of a grisly twenty-year war, there was more than a little disquiet about what we would be facing. As it turned out, arrival was anti-climatic, and as we walked down the stairs onto the tarmac into a balmy night, there were only a few military guards in sight. Customs was blessedly routine and we were “most welcome,” but where was the welcoming committee we’d heard about?

They were waiting, but I digress…

2

WHY: What I knew then

The Back Story

It seemed like a good idea at the time. No, it wasn’t nearly so cavalier as that in one regard, but it was purely spontaneous in its infancy.

Fast approaching the age when people talk of retiring, traveling, and sipping margaritas, I had no retirement funds; most of my net worth was tied up in my home, and I’d been running a slightly left-of-field consulting business for fifteen years and was facing burnout: physically, spiritually and mentally. My work had been essentially spiritual in nature, but I’d had to cloak it to make it commercially viable. Twenty years ago, it was just too out there, and selling it meant selling me and my credibility.

I recounted the great adventures that had tested me—the year cruising on a sailboat, Europe alone, Tunisia, Morocco—and realized the gypsy in my soul was feeling neglected and thinking the good times were behind her. She had grown bored by both comfort and stress and needed another adventure—one of which stories are born—another year of living “dangerously,” but one that might make a difference in the world.

Following a wine-fueled middle-of-the-night conversation with a friend, who asked, “Why not Peace Corps?”—I laughed, thinking I was too old. A week later, I fired off the first online query and thought: what’s the worst that can happen?

Friends chimed in, some knowing I’d always questioned the status quo, sought the unknown, and embraced change; others were convinced of my stupidity.

As I deliberated about how to catalyze the change I was seeking, a few things became absolutely clear:

I needed stillness.

I needed to step-out to get it.

I needed to live the work, not sell it.

And so, I jumped.

And never looked back.

Hurry Up and Wait…

And so it began. When I got a nibble back from my query, I discussed my idea with my sister, who had, in the early, free rein days of Peace Corps, volunteered in Tunisia with her new husband. She summed-up Peace Corps in two words:

Life-defining.

At my age, would it still be life-defining? Could it redefine the second half of life? Knowing their experience and mine would be radically different didn’t deter me. I gulped and plowed ahead with exhaustive questionnaires and essays designed to glean every tidbit of experience I’d had in my life. And I’d had a lot of experience.

Following a positive response, I had permission to proceed with the medical phase, equally daunting: EKG, colonoscopy, redoing all of my childhood vaccines. (Peace Corps held a low-opinion of baby-book immunization-records.) Medical records for some things had to be excavated from a vault somewhere.

On my end, there were hard deadlines, only to be followed by an interminable wait for PC’s response. They even sent a letter defending the waiting as good practice for what awaited us as volunteers.

I was not amused, but my commitment had taken on a life of its own and there was no backing down at that point.

Off Like a Turd of Hurdles

My initial placement was Belize, with a presumed departure a few months out. I began packing and purging household items, trying to sell my house, and letting clients know of my plans in case they needed to schedule appointments. All they heard was: “She’s gone.” My business shut down at a calamitous speed, the house didn’t sell, and Belize didn’t materialize. What a mess.

After the tentative Belize placement, I consulted a highly touted Australian psychic, who saw me with very dark skinned people in a hot, desert-like area; I dismissed it. I’d told her of a prediction that I would study with a Shaman during my service, to deepen my innate skills, to which she replied, “You are the Shaman you will meet; and you’re not going to Belize.”

Sure enough, the Belize placement was withdrawn and months later, I was offered Eastern Europe or Africa. I knew Eastern Europe, with its frigid winters, would spit me out after the first winter, because I can be a miserable, black-hearted shrew with a tendency to hibernate and whine when I’m cold. Besides, Africa seemed like the more quintessential Peace Corps experience I was seeking.

When the Uganda placement finally came through, the departure date was less than a month away, so life became a fire-drill. With the house still on the market and fully furnished, angst was at full throttle, and I had a decision to make.

I’d bought my home from friends who carried the loan and needed their funds. If I couldn’t sell and pay off the loan, I couldn’t leave. When it came down-to-the-wire, they extended the note for one year, which meant I could leave, but without the cutting of ties I’d wanted. It was a deal.

3

Fixin’ to get Ready

With the requirement to sell off my plate, I needed to haul ass. The to-do list was exhaustive, including everything from finding renters, water-purifiers, medical supplies, and clothes for multiple climates, to updating website contacts. Chaos reigned.

A week before leaving I had the mother-of-all garage sales.

A few days before leaving, I was giving away what didn’t sell and moving everything else into an 8 x 10 storage unit.

The daybefore leaving found me installing automatic soaker hoses to protect the old foundation and giant maple trees.

With that done, I thanked the house for three good years, did a blessing for the future residents, locked the door, turned my back, and walked away. Then I drove to the Subaru dealership, sold them the Impreza I’d bought two years ago, and took a deep breath as I climbed into my friend’s car to drive into the rest of my life.

No car, no house, no clients, no income, and no friggin’ idea of what was coming next, except to climb on a plane to go live in the heart of Africa.

~~~

I had packed my two suitcases a dozen times. My sons helped me with things like a Leatherman multi-tool, solar chargers, first-aid supplies, water purifiers, book lights, etc. Both have had survival and EMT training, do extreme sports, and have learned to pack light, but far beyond their guidance with gear, their encouragement and support meant I could leave knowing they were OK with my decision.

On their recommendations, I revisited my packing choices with the ruthlessness of an assassin and eliminated everything that didn’t have multiple uses. The list of the 110 items that made the final cut included a French Press, antibiotics, haircutting shears, duct-tape, Leatherman tools, and earplugs.

Blog Post: July 31, Pre-Departure

Whew!

Well—it’s here: the night before leaving and a race to the finish. It really has taken a village to get me out the door and I’m filled with gratitude. Closing down the accumulated possessions and detritus of 63 years is daunting, and the requirement to get a house ready to lease created the perfect storm. Still, it is done and what is not—well—I suppose that’s part of the journey: time to let go and trust.

Suitcases have been weighed and measured to conform to Peace Corps regulations—it’s about to get real!

4

Boot Camp: You’re in the Army Peace Corps Now

Week One

Despite the differences implied by their names, the military and Peace Corps have more in common that one might think. For starters, members of both are serving their country, often living overseas in minimalist, if not miserable, conditions. Both put their members in harm’s way, even if unwittingly. In some justifications, both are serving the cause of peace and both can make your life a living hell during training. At least the military owns up to it. Also, the military is paid and has benefits. Peace Corps Volunteers get a stipend averaging about $300 US a month, and there are no post-service benefits. We know this going in, so there’s no defense there, just a topic for discussion.

I am not going to sugarcoat training; ours was not for the weak-of-spirit or constitution. The blogs I wrote in Peace Corps were “politically correct,” since they were public domain and PC let us know they would be read. Required on every blog was the disclaimer: The views expressed herein are not those of the United States Government or Peace Corps. And truthfully, I didn’t really want to alienate Ugandan readers or our trainers, who, as a rule were fun, smart, committed, passionate and compassionate people with our best interests at heart, and who put up with a lot of crap from trainees who entered with a first-world attitude and no real-life experience. True, there were a couple who had either been there too long or whose behaviors telegraphed hostility, but they were in the minority.

In the military, the first thing done to new recruits is to remove as many as possible of the identifiers that make a person unique, starting with clothing and hair style. Military sends personal clothes home in a box. As a mother, receipt of that box after my oldest son enlisted was terrifying, until I realized he was still alive and well, just depersonalized. Then comes the head-shave, and sleeping in dormitories, and enduring the untold indignities and depersonalization known as BOOT CAMP. Alien foods devoid of personality are the order of the day, as close quarters and stress often result in epidemics of various maladies.

And so it was with Peace Corps—with the exception of the head shaving and taking away your street clothes, which have already been left behind in favor of culture-friendly clothing that can endure termites, bleach, possibly being washed on rocks, and other forms of abuse. The mandate is to be as unobtrusive as possible for safety as well as respect. Customary personal hygiene and beauty rituals all but ceased.

We all understood this going in and it was appropriate, but the totality of these changes coupled with being away from our families, flush toilets, showers, familiar food, and sanitation, was the perfect setting for emotional and physical fatigue, dysentery and unhealthy coping behaviors. There was very little adjustment time between our First World lives and the realities of living in the Developing World.

For the first week, we lived in a compound called Banana Village—eight to twenty people per dorm with one bathroom and one cold shower per unit; sanitized drinking water; breakfasts of stale bread, boiled eggs, peanut butter and pineapple—nutritious, but not soul-nourishing.

Lunches became local food pretty quickly, transitioning to starch-heavy meals, and lots of beans. A typical meal, nearly devoid of any salt or seasonings, served every day for ten weeks, could explain why women typically gained ten-to-twenty pounds and men lost the same. It’s an unfair universe. Here was the menu:

•White potatoes

•Sweet potatoes (not a yam, barely sweet)

•Rice (often with bits of rock)

•Posho (hard-cooked grits)

•Matoke (steamed and mashed green bananas)

•Some form of meat butchered by hacking, leaving bone shards

•Beans (with the occasional rock)

•Greens or shredded cabbage

•Water/ hot tea

•Ground-nut paste (a pinkish, peanut gravy)

•Pineapple or bananas

By day three, half of the women’s dorm had serious dysentery and the rest of us had the diarrhea that comes with most foreign travel. Thank goodness for my personal stash of Cipro.

In the midst of all this, though, I was able to step out and marvel at being surrounded by sounds of giggling children, chattering monkeys, and bird-calls that sound like laughter. A few days in, someone apparently dispatched the rooster that had been crowing all day and night; things got quiet, and lots of chicken appeared on the buffet table! An old camel arrived in the village; we hoped camel meat would not follow.

Antimalarial drugs were started immediately, and, although we had to be up to date on the usual childhood vaccinations, plus a last-minute Yellow Fever Vaccine, we hadn’t even begun the multiple rounds of required immunizations: Hepatitis A and B, rabies, flu, meningitis, typhoid, tetanus. A few of us, myself included because of a friend’s ordeal with Guillain-Barre syndrome, tried to opt out of the flu vaccine and were asked when we’d like to go home.

In short, the first week was hell. That, I suppose, should have been expected, but hell just took on greater dimensions as the next two months of training progressed. Had I known…

Just about the time we thought we’d reached our limit, admin arranged a trip to the zoo and botanical gardens; a sorely-needed diversion.

One day, we were taken to Kampala for an introduction to the city—and its taxi parks—that would become the transit hub for travel in-country. It was also to become our go-to city for everything from a haircut to medical care. We treated it as a treasure hunt, and the prize was survival.

Maybe visitors traveling in the US from smaller countries have a similar indictment of New York City or DFW airport, and I suppose it’s all in what you get used to, but it was terrifying at first glance, although a little less so over time.

The Ninth Ring of Hell: Taxi Parks

We were introduced to the two taxi parks, which on the face of it sounds reasonably civilized. Nothing could be further from the truth. Imagine a hornet’s nest that has just been kicked: angry hornets buzzing in all directions, stinging whoever comes near. Now, imagine that those hornets are spread over an acre, and they are now 16-passenger taxis filled with 24 people, all parked or moving in different directions metal-to-metal, honking, drivers yelling. Add a zillion vendors of every known substance, hawking their wares; thieves looking for fresh victims; molesting hands sweeping over you; snarling wild dogs; and begging children, and there you have it: the Kampala taxi park. Because of its location in the lowest part of the city, it floods quickly, liberating latrine sewage and other assorted garbage. Add fumes and other smells.

All of us came back in shock, realizing what we would have to negotiate when transiting Kampala between destinations—essentially a requirement. At the end of that day, I was as near to tears as I had ever been before or since.

Travel in general is not for the faint-hearted. Squalid latrines, goats, chickens, people sitting on top of you, crying babies, suffocating dust, lack of ventilation, and countless other indignities were just part of public transport, but braving the taxi park required a group, or a level chutzpah I did not possess. Some of the younger ones brazened through, but several of those were also robbed, molested, or otherwise accosted.

In short, it was the ninth ring of hell.

Journal: August 8, Training

Monday—the first night’s sleep with no interruption. Wonderful. It’s a gorgeous cool morning with the usual creature cacophony. As an act of self-preservation, I’m learning to love the new coffee drink: instant coffee, sugar and hot milk. I’m a Louisiana girl and was weaned from mother’s-milk to coffee-milk. Dark-roast flows through my veins. Today brings a different perspective of Kampala, now that we’ve survived our trial by fire. We straggle into an open-air thatched gazebo along with the monkeys, and are introduced to Ugandan English (Uganglish)—an interesting blend of proper British English and Luganda expressions. “Now means whenever; “now-now” means NOW sort-of! NOTHING in any language means NOW in Uganda—although chawa adi in Acholi comes closest.

We got our language assignments today and mine is Acholi, meaning I will be in the north, near Gulu, the area hit hardest by a recent war and the same region mentioned on the Peace Corps website as strictly off-limits to PCVs. That was a little unnerving.

At first I was alarmed and a little disappointed, due to its isolation, but I believe it offers great potential and I love our group.

The day was improved by being able to talk to my sons, Travis and Brett, after buying airtime. Knowing we will have greater contact than I first thought will make it easier to deal with other challenges.

~~~

The gazebo was where most of our training occurred, including that day’s medical session and receipt of our medical kits: a plethora of tiny packets of generic antihistamines, antacids, condoms (in brown-camo packaging, the necessity of which I question), and analgesics—any of which would be hard to find in a local pharmacy, where we would likely be “diagnosed” with a touch of the Malaria and be given anti-malarial drugs. For anything beyond the basics, getting to Peace Corps Medical would mean a day’s ride.

For stomach maladies, we were told to give it a day or two, to be sure it was more than just the trots, but by that time, if it was more serious, the ride on public transport with no bathroom could be grim and humiliating. If we were deathly ill, PC would possibly send a car, but sciatica, “normal” dysentery, Malaria, parasites, conjunctivitis, etc. wouldn’t make the cut.

Journal: August 10, Training

This is our last day at Banana Village, so we have time off to repack in preparation for taking only ONE suitcase to HomeStay, our-home-away-from-home for the next two months. We’ve been instructed on what our roles will be there, as well as what we might encounter with our families. I’ve spent little time processing feelings at this juncture, but I’ve been happy about emerging friendships; and being busy contributes to not feeling homesick. Mostly we are just exhausted. There are still six volunteers down with dysentery. Some of it is jet lag I suspect, but we are in such learning, emotional, and sensory turmoil that all systems are stressed to the limit.

Periodically though, we have time to wander through the community, typical of small villages: red dirt roads—impossible to ride a bike on, but people do—boda-bodas (motorcycle taxis) racing everywhere and in all directions at once, cars, dukas (little shops) made of any kind of wood that can be thrown together with a door—selling everything from TP and beer to sim-cards!

We get our HomeStay assignments tomorrow as we move into Wakisu, so tomorrow will be spent in someone’s home.

Alliances have already been formed and it’s clear who the friends will be, although we may not have access to them.

PostScript

There is a saying here that you’re not really in Peace Corps until you’ve “shit your pants.” Just as I was walking to the bus yesterday—it came without warning. Thank god I was wearing a skirt. I stepped out of my underwear, threw them in the garbage, and climbed aboard. Nothing left to do but to go with it.

I’m officially in Peace Corps.

5

HomeStay

The first ten-weeks of Peace Corps Service are dedicated to training on topics ranging from safety, using a night bucket, how to take a bucket bath, and doing laundry (no kidding), to language and customs. What’s a night bucket? Think chamber pot. It’s not safe to go outside to the latrine at night: there’s no light, but there are snakes, feral dogs, holes to step in, and the occasional collapsing latrine. A few years ago a volunteer fell through a latrine floor into four feet of fermenting feces and it was too deep to climb out. I hear he was treated with every known antibiotic and sent home. So compelling was this threat that more than once I chose the bush and the possibility of a venomous Black Mamba over a latrine with a wooden floor.

The initial stage behind us, the remainder of the training took place in the small town of Wakiso, where we lived with families who had applied to have a PCV live in their homes.

Peace Corps pays an allowance to cover food, and some families make out pretty well from this. A few clearly do it for the money, others for the prestige, and others, like mine, because they really love the cultural exchange.

When some friends asked their HomeStay host what prompted her to participate in the program, she replied that she’d tried raising a couple of goats for extra income, but PC paid more, even if volunteers were more trouble!

It would appear that we are one notch above goats on the profit scale.

Florence, My Host

The gods must have been smiling on me, because I hit the jackpot with Florence, a beautiful, educated woman with short-cropped hair, excellent English, a ready smile, and a warm heart. Beaming with excitement, she rushed over to give me a real hug, which I sorely needed. Florence shared her mud-brick home with two of her orphaned grandchildren, Nabossa and Ernest (ages five and eight respectively), and two young adults rescued from dire circumstances. Nearly everyone in Uganda is housing someone outside of family.

As a property owner—a rarity among women—and the only one in her village fluent in reading and writing, Florence was elected Local Commissioner. She was proud of her bookcase displaying books gifted by previous volunteers and let it be known that her dream was to start a library in her home, because she knew the community would never do it. Ugandans are the first to tell you: “If you want to hide something, put it in a book.” Florence, however, as the daughter of a medical doctor who had been the physician for two of Uganda’s presidents, had attended the best schools and married well, so she was a reader.

In one of Uganda’s military coups, her husband was imprisoned for alleged disobedience to the regime that took power. When he died there, Florence, fearing for her life and that of her four young children, fled north, across the Nile, and into the bush where she raised her children in hiding, scavenging for food and shelter.

Sometime later, her brother-in-law discovered them and deeded Florence the small plot of land, including a tiny mud-brick building, inherited by her deceased husband. Since Ugandan wives often inherit nothing and seldom own land, that act of generosity was nothing short of miraculous and gave Florence a fresh start. She raised her children in the shed, surviving off gardens she’d planted, as she made enough bricks from the soil around her hut to build a house, one room at a time.

By the time I met Florence, three of her children had died from HIV and other causes, which is how she came to be raising her grandchildren. Her surviving son is married, has a good job and lives wherever he needs to for work, a common practice in much of Africa.

The House

Florence’s house, situated on a hill, held some prestige with its tin roof and small front porch bordered by flowers (another rarity). Out back was a vegetable garden with lemongrass for stomach aches, elephant grass for the cow, a banana tree, and the standard issue cassava, beans and potatoes. A separate building—the boys’ quarters—large water tank, clothes line, and kitchen shed where the goat slept at night and where Florence had first raised her children, filled in the backyard. A cow for milking and Pinky, the watchdog, completed the ensemble.

Florence’s house boasted a flush toilet and bathing room, both of which were luxuries, because both were usually relegated to the backyard and offered little privacy. The toilet flushed directly into the side-yard, using water poured into the bowl, usually with water left over from a bucket bath.

Although Florence had the foresight to wire the house for electricity as she built it, she couldn’t afford the utility connection fee. Every time she had a few extra shillings, she bought a fixture, then a stove—all waiting until she had the hook up fee: $100 US.

Every task done in the twelve hours of inky, Equatorial darkness is done by the dim glow of a kerosene lantern.

Knowing her story and her steadfast resolve to take care of her family and her community, my gift to her when I left was the money to have power brought to the house. That one simple act changed everything.

My Room and Life During Training

My room—mercifully adjacent to the toilet, had a small window overlooking the backyard, and two bed frames, one of which I used as a rainy-weather clothesline and storage area, the other, my bed. I considered myself extremely lucky.

Peace Corps furnished a foam mattress, insecticide-treated mosquito net, pillow, blanket, bathing bucket, and an itty-bitty solar reading lamp. We provided our own sheets, towels, night bucket, toilet paper and all else. The headlamp I brought with me was a survival essential since, in the rainy season one could never depend on being able to charge the solar lamp. Candles were the soft wax variety that stick to the floor, melted in about three hours and offered functional light, but not enough for studying. Therefore, we all schlepped solar lamps, phones, cameras, and computers to training, in the hope of safely charging there. Florence warned me never to leave my solar pack unguarded at her house, because it would “grow legs and walk off.”

Every couple of days I found a fresh gallon of boiled water at my door; boiled over a wood fire, it always had a smoky taste, as did the mild African tea she boiled for my breakfast. In fact, everything smelled of the smoke that wafted from the outdoor kitchen—infusing freshly washed clothes that hung to dry, bedding and anything hanging in my room, as well as my hair. I would later miss that smoky tea and the emotional comfort it offered in those days.

Along with smoky tea, we were acclimating to Uganda’s equal portions of daylight and dark. We awoke and dressed in the dark, grabbed a backpack loaded with books, extra shoes and other paraphernalia and hiked forty-five minutes through the brush and mud, over streams and barbed wire, past goats and cows and chickens and kids to the training site. Often encountering angry Ankole cows along the way, one member of our motley group was lifted onto the horns of a particularly ill-humored beast, but pulled off by a friend before being harmed.

By the time I’d dressed, Florence had a boiled egg, bread and tea waiting for me on a neat placemat at the dining room table. Pinky-the-dog waited patiently for me to finish.

Arrival at training ushered in eight hours of disorganized presentations and games, interminable waits, and random cancellations. As newcomers used to a westerner’s allegiance to the clock, these delays were infuriating, but the next two years and the realities of life would mellow my perspective. Rain, blowing through the windows, often shut down everything with its deafening roar on the tin roof, and often followed us home.

By the time we walked home and had dinner, it was dark again, time for another bracing bucket bath and hunkering down under the mosquito net to study until the solar lamp died, then sleep.

HomeStay was challenging on many levels, so it was a godsend to be with a good family. Mine was lovely in every respect, but HomeStay pairings were a crapshoot. I assume some families felt the same way in reverse.

Living with a family put us a little ahead of the curve by the time we went to site, by allowing us time to adjust to radically altered circumstances while we still had a safety net. The stresses of training, culture shock, dysentery, having to poop in a fly-infested latrine or a night-bucket, mosquitoes, cold bucket baths, strange diets, being away from home, language, and living under a microscope continued to wipe us out on every level.

Our Ugandan families provided an anchor and a semblance of oversight, since they were aware if we didn’t make it in at night or if we were sick. Florence made me lemongrass tea when my stomach acted up, made sure I had dinner upon my arrival home, and that it was something I liked, not always the case with other volunteers who frequently had to wait until 10:00 PM for whatever food was offered. A fried egg on bread worked for me and also meant we weren’t tied to each other’s schedules. Florence’s flexibility and attitudes were clear evidence of her positive history with foreign visitors, and her innate generosity.

Mud was a constant companion in rainy season, and the powder-like quality of the dirt, when mixed with water, reminded me of my aunt’s favorite expression, “slick-as-goose-shit,” as we tried to keep from slipping on our walks to training. We practically lived in gumboots, which were scrubbed at each end of the daily trek and lugged our regular shoes along to wear at training. I was completely taken aback the first morning I came out to see that Ernest had proudly washed my shoes for me.

I was given such sweet care.

Wakiso

Wakiso treated us well, even though we were all identified as, “Hey, Muzungu!” Small enough that we couldn’t get into too much trouble, it offered a couple of beer joints, one restaurant a serious hike away, and a hardware store that sold the mud-boots we needed.

It was essentially one long, main road through town with a few crossroads, so it was easy to find most of whatever was available (TP and chocolate topping the list) from the dukas or small open-air market. Our focus was pure escape provided in the form of beer, Smirnoff Ice and chips (fried potatoes), sufficient for the most part, because we were too tired on the weekend to do anything but wash clothes, study, and collapse.

During a couple of those weekends, I taught Florence how to knit and make dolls to sell, while the kids watched. In a couple of days, Ernest, with his enviable aptitude for spatial memory and motor skills, had not only produced a doll, but had taught a couple of other people to knit as well. I also read to Ernest and Nabossa, and taught an energy-healing class to a group of PCVs in Florence’s living room.

It felt good to tap into some of my old life. Reading to Ernest and Nabossa was good for the soul and stirred memories of hours spent reading to Travis and Brett, and teaching the healing class tapped into my past as an energy worker, though I was careful to clear it with Florence beforehand. In Uganda, such things can be considered witchcraft, which is still alive and well.

Florence had had her own experience with that, prompting her to have both of her grandchildren marked at birth—piercing her grand-daughter’s ears and making a small cut on Ernest’s arm. Small children were still used in ritual sacrifice, but those with any marks on the body were rejected. That knowledge saved Ernest’s life after a couple of men abducted him while he was walking to school.

Thanks to Florence’s marking, theylet him out and sped away.

6

Pinky, the Teflon Dog

I don’t think I can really do justice to Pinky, whose purpose seemed to be to love Muzungus—and especially this Muzungu. The fact that she has her own chapter is testimony to how much her affection meant during those early days.

First of all, who in Uganda has a dog named Pinky? In fact, most Ugandans don’t have pets, period, but Pinky was loved, and was a good Mama dog even before she became a Mama. Muzungus were her pack and she mothered us well.

Blog Post: September 5, Training

Dogs here are guard-dogs, fed scraps, and often mistreated. Wild dog packs are known to eat livestock and attack people who dare to venture out at night, even the short distance to the latrine. We don’t have a latrine, but if we did, I know Pinky, a nondescript female of unknown years and loyal watchdog, would be at my side. The fact that she is mostly a pet makes her an aberration.

All dogs in Wakiso look alike with few modifications in design, save personality and the look in the eyes. There are no spotted dogs, black dogs, different breeds of dogs. Pinky is happy and gentle, with soft eyes and a sweet personality.

She has adopted me as part of her pack, follows me to school and to town-and-back, likes to curl up next to me anytime I’m outside; even checks on me to see that I’m keeping up and leaving for training on time. She has accepted other Muzungus in her pack as well, but I’m her favorite, until someone offers her a food handout. Then she turns fickle.

Because we are attached to Pinky, it was a great drama when she was hit by a car yesterday. Neither cars nor boda-bodas have any regard for people, much less animals. I heard the car smack Pinky and keep on going as Pinky yelped and was hurled off the road; the whole Peace Corps community knew about it within moments. We searched.

I called Florence, whose response was, “Ah! She is a dog! Don’t be fearing!” Sure enough, Pinky returned home with little more than a scrape on her lower lip. How she was not injured, we don’t know. Except, there’s an expression that everything is tougher in Africa because it has to be.

Pinky is now known as the Teflon Dog and I’m wondering if I will be tougher after two years in Africa.

~~~

Pinky was precise about getting me to training on time and became very agitated on weekends when I took my time at breakfast, often daring to come inside to get me. Her habit of sleeping under my window was a great comfort for both of us.

Dogs were absolutely banned from the training compound, but Pinky expertly wormed her way into the hearts of even the guards by refusing to leave without her Muzungu. She became the surrogate for pets left at home, and the day I left Wakiso ran behind the bus until she couldn’t keep up. There wasn’t a dry eye in the group. Pinky would be missed.

A year or so after I left, Pinky had had her first litter of puppies, some of which went to Peace Corps volunteers, continuing her legacy in the hearts of trainees. She continued to love Muzungus and was often seen trailing along with them through town.

Ultimately, a thief stole Pinky in preparation for his return a few nights later for the family cow. Pinky’s loss was emotional, but the loss of the cow was a serious blow to the family, both nutritionally and financially.

Florence recently let me know they have another dog, but there will never be another Ugandan Village Dog like Pinky.

7

Haircuts and Chocolate

Self-Maintenance