4,95 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: T2Pneuma Publishers LLC

- Kategorie: Religion und Spiritualität

- Serie: Christian Spirituality

- Sprache: Englisch

What does it mean to be created in the image of God? This is the core question in Christian anthropology and it is surprisingly important in understanding everything else. Anthropology is the study of human beings, the who question of philosophy. As Christians, our identity is found in Jesus Christ, but exactly what does this imply?

Because we are created in the image of God, he is familiar and we immediately recognize him (metaphysics). Because we worship the God who created the universe, we expect the universe to be orderly and worthy of scientific study (epistemology). Because God loves us, we can love those around us who make up God's family (ethics). Our anthropology is accordingly an interpretive key that colors how we see everything else.

In exploring this question, Image and Illumination offers over forty devotions containing a reflection, prayer, and questions for discussion. These devotions are organized into these chapters: Introduction, Image, Fall from Grace, Illumination, and Restoration.

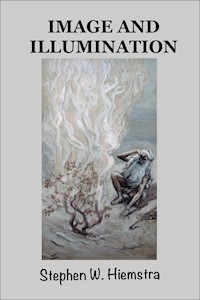

Cover art is by James Tissot (1836-1902): Moses Adores God in the Burning Bush. French Jewish Museum, New York.

Hear the words; walk the steps; experience the joy!

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 256

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Ähnliche

Contents

Endorsements

Other Books by the Author

Title Page

Copyright

Preface

Introduction

The Divine Image

The Fall from Grace

Illumination

Restoration

The Image

Image and Illumination

Image of God

God's Attributes

Trinity

Surface and Depth

Heart and Mind

Image and Personhood

Discernment

Music as Image

God's Image in Christ

Fall from Grace

Image and Stability

Sin and Evil

Diminishing the Divine Image

Meta-Narrative Angst

Obsessing about Unconditional Love

Mankurt Phenomena

Obsession with Youth

Mass Shootings

Apathy and Difficult People

Lost Opportunities

Limits to Progress

Lost Transcendance

Illumination

Illumination and Ethics

Image and Word

Christ Extends the Law

Faith and Works

Intrinsic and Market Values

Creation and Stewardship

Image and Consciousness

Kingdom of God

The Church

Restoration

Centering on God

Measured Blessings

Complete Restoration

Spiritual Disciplines

Numbering Our Days

Under God

Conclusion

Parting Words

References

About

Notes

ENDORSEMENTS

Image and Illumination is a book you'll want to read and reread, a treasure trove of spiritual insight. Through thoughtful interpretation of Scripture, the author applies insight in a way to challenge the believer to a greater appreciation of their faith.

Linda Wood Rondeau

Author of Who Put the Vinegar in the Salt

Stephen Hiemstra has written a series of brief textual expositions on a variety of interesting, important, and sometimes difficult theological issues. He brings to the task his own lively imagination that makes some fresh thinking possible. The book is written in a way that invites readers into the probes as well. Readers may expect to be led in new directions by this book.

Walter Brueggemann

Columbia Theological Seminary

My good friend Stephen Hiemstra continues his journey to write books on Christian spirituality that anyone can understand. He has a way of writing that not only brings clarity to these complex theological topics but brings them home to the reader, so they connect with these truths on a personal level. One of his first books, A Christian Guide to Spirituality, is a foundational classic that I have used to teach several Bible studies. In this latest book, he explores the divine realm and God’s intrinsic connection with humanity. Not afraid to take on complex topics, Stephen confronts several mainstream issues head-on. Each chapter concludes with several thought-provoking questions, so I expect this book to be added to my collection of discipleship resources. You will thoroughly enjoy this latest classic, and I encourage you to read his other books.

Eric Teitelman

House of David Ministries

In Image and Illumination, Stephen W. Hiemstra tackles that most basic of human questions: What does it mean to be created in the image of God? Through modern-day examples and scripture, he draws the reader ever closer to the answer found in Christ. A must-read for anyone wrestling with this question.

Sarah Hamaker

Author of The Cold War Legacy series

Many of us live with the sense that all is not as it should be in this world. That our world is both beautiful and somehow broken. In Image and Illumination Stephen Hiemstra peels back the layers of our modern world to reveal not just what things should be, but what they one day will be through God's work in our world. You will not regret your time immersed in this book.

Aaron McMillan

Pastor, Centreville Presbyterian Church

A Christian Guide to Spirituality

Called Along the Way

Ein Christlicher Leitfaden zur Spiritualität

Everyday Prayers for Everyday People

Life in Tension

Living in Christ

Masquerade

Oraciones

Prayers

Prayers of a Life in Tension

Simple Faith

Spiritual Trilogy

Una Guía Cristiana a la Espiritualidad

Vida en Tensión

IMAGE AND ILLUMINATION:

A Study of Christian Anthropology

Stephen W. Hiemstra

Image and Illumination:A Study of Christian Anthropology

Copyright © 2023 Stephen W. Hiemstra

ISNI: 0000-0000-2902-8171, All rights reserved.

With the exception of short excerpts used in articles and critical reviews, no part of this work may be reproduced, transmitted, or stored in any form whatsoever, printed or electronic, without prior written permission of the publisher.

T2Pneuma Publishers LLC

P.O. Box 230564, Centreville, Virginia 20120

www.T2Pneuma.com

Names: Hiemstra, Stephen W., author. Title: Image and illumination : a study of Christian anthropology / Stephen W. Hiemstra. Series: Christian Spirituality Description: Includes bibliographical references and index. | Centreville, VA: T2Pneuma Publishers LLC, 2023. Identifiers: LCCN: 2023900608 | ISBN: 978-1-942199-43-4 (paperback) | 978-1-942199-90-8 (Kindle) | 978-1-942199-71-7 (epub) Subjects: LCSH Spiritual life--Christianity. | Spirituality--Biblical teaching. | Theological anthropology. | Theology, Doctrinal. | Image of God. | BISAC RELIGION / Spirituality | RELIGION / General Classification: LCC BV4501.3 .H45 2023 | DDC 233--dc23

All Scripture quotations, unless otherwise indicated, are taken from The Holy Bible, English Standard Version, Copyright © 2000; 2001 by Crossway Bibles, a division of Good News Publishers. Used by permission. All rights reserved.

Special thanks go to my editors: Jean Arnold, Sarah Hamaker, and Nohemi Zerbi

Cover art is by James Tissot (1836-1902): Moses Adores God in the Burning Bush. French Jewish Museum, New York (https://TheJewishMuseum.org). Used with permission (© SuperStock; www.agefotostock.com)

Cover by SWH

PREFACE

What does it mean to be created in the image of God? This is the core question in Christian anthropology and it is surprisingly important in understanding everything else. Anthropology is the study of human beings, the who question of philosophy.

When René Descartes (1596–1650) wrote, “I think therefore I am,” he neglected to talk about the preconditions for his statement, which must have annoyed his parents. Why did he have time to consider the question? Where did he get the words to express the thought? Why did anyone else pay attention? Who was this guy anyway?

While we might neglect to consider who Descartes was, his role in modern philosophy is undeniably critical in the development of the modern era and, by inference, the postmodern era. The who question is all about identity, something obsessed about in this narcissistic age.

As Christians, our identity is found in Jesus Christ, but exactly what does this imply?

The Image

Probably the most inconvenient verse in the Bible is this: “So God created man in his own image, in the image of God he created him; male and female he created them.” (Gen 1:27) We participate in God’s eternal nature and reflect God’s image primarily when we are joined with our spouses to accomplish God’s creative mission: “Be fruitful and multiply and fill the earth.” (Gen 1:28) What could be more inconvenient in this narcissistic age that we live in than to be bound to a spouse in accomplishing our most basic purpose in life?

This inconvenient verse implies that we cannot answer the who question without considering the family. Because Descartes’ social position—who he was—is a precondition for all that followed, likewise Christian exploration of epistemology and ethics hangs on who God is and who we are together in his image. If Descartes had been an orphaned, penniless drunk in the sixteenth century and thought the same deep thoughts, the modern and postmodern eras may have been nipped in the bud.

Fall From Grace

While God is sinless and we were created sinless, sin has been hardwired into the human psyche since the Garden of Eden. Original sin arises whenever you have two babies sharing one toy: No one is innocent. Worse, our collective sin taints us even when we try to avoid personal sin.

Moses anticipated the course of human development in Deuteronomy 30:1–3. You (plural) will sin; be enslaved; and cry out to the Lord. God will send you a deliverer and restore your fortunes (Brueggemann 2016, 59). This pattern, called the Deuteronomic Cycle, outlines biblical history and with it the rise and fall of nations. The implication for postmoderns is that cultural progress—however defined—is temporary and subject to corruption.

The question posed by scripture when we witness sin and societal decay is: Are we in the community of faith going to pray for sinners like Abraham witnessing Sodom and Gomorrah (Gen 18) or run away from our prophetic duty like the Prophet Jonah? (Jonah 1) Like Abraham and Jonah, we have been told in the Book of Revelation (Rev 20) that the destruction of sinners is coming. How will we respond?

Illumination

Being created in the image of God implies that by nature we want to be like God. This is image theology. What could be more ironic than having human ethics founded on a principle that we normally mock in simians: Monkey see; monkey do? Even, the Lord’s Prayer reiterates this principle in the petition: “Your kingdom come, your will be done, on earth as it is in heaven.” (Matt 6:10)

What is God’s first act of creation after creating the heavens and the earth? The Bible reads: “And God said, Let there be light, and there was light.” (Gen 1:3) Then, God declares the light to be good. Goodness and light are equated as God begins by creating a moral universe. Imitating God implies that we should want to be moral, just like God. It is interesting that Jesus’ parables all sharpen the image of God that we are given to help us pursue that impulse.

Being created in the image of God accordingly implies a moral mandate even before human beings are created. The who question and the primacy of relationships dominate the discussion even before the advent of sin, the introduction of community, and the giving of the law, but morality itself requires thinking and volition—you have to want to be good essentially because we are sinful by nature. God does not discount feelings and relationships: Feelings and thinking are inseparable.

Restoration

Spirituality is faith lived out. After we have repented and been baptized in the name of Jesus Christ, we receive the gift of the Holy Spirit (Acts 2:38), but we are still tempted, still sin, and still live daily in a fallen world.

Life is full of Gethsemane moments where we are confronted with painful choices (Matt 26:39). Do we turn to God in our pain and give it over to him—centering our lives—or do we turn into our pain and sulk—de-centering our lives? Because our personalities and our culture are formed by our daily answers to this question, it is important that we focus on God even as our eternal destiny is secure. Christian joy is a life well-lived where we strive to realize our potential.

It is helpful in this context to distinguish two types of blessings. The first type is obvious: When you win the lottery in life, you feel blessed. This is an example of God’s unmerited grace. The second type is not obvious. You did what God expected of you, like the dutiful servant (Luke 17:7–10), and did not fall into life’s traps, sin, and temptations like those around you. Looking back on a life well-lived, this second type of blessing becomes more obvious because one is more likely to realize one’s potential. Centering our lives on Christ is like having a spiritual compass.

The mark of a de-centered life is greater temptation to sin, yielding to unclean desires, and being gripped by self-destructive tendencies—a life of missed opportunities is poorer, unfocused, and filled with tragedies. Thus, the faith journey is particularly fruitful for those struggling with besetting sins, gender confusion, and mental illness.

Faith matters; right now it matters a lot because God in his mercy delivers on a familiar promise: “A thousand may fall at your side, ten thousand at your right hand, but it will not come near you.” (Ps 91:7) At this point in time, lost opportunities are a pattern. Life expectancy in the United States is falling due to preventable causes—suicide, drug overdoses, and refusing to be vaccinated. Fertility rates and living standards are also falling, all indicators of a society under stress and under performing.

Return to Christian Spirituality

Anthropology is an important component of Christian spirituality. A complete spirituality addresses each of the four questions typically posed in philosophy:

1. Metaphysics—who is God?

2. Anthropology—who are we?

3. Epistemology—how do we know?

4. Ethics—what do we do about it? (Kreeft 2007, 6)

My first two books—A Christian Guide to Spirituality and Life in Tension—address the metaphysical question. My third book—Called Along the Way—explores the anthropological question in the first person. My fourth book, Simple Faith, examined the epistemological question. My fifth book, Living in Christ, explored the ethics question. Here in Image and Illumination I return to Christian anthropology from a community perspective and in view of my other explorations.

I thought that I was finished with Christian spirituality as a writer, but anthropology is at the heart of many of today’s deepest divisions and I have been repeatedly nudged to write more about it. It affects the other three components of our spirituality—metaphysics, epistemology, and ethics—so profoundly that skipping over a more formal treatment leaves the other components wounded. So here we sit wounded as individuals and as a church.

Again, I take up a subject, not out of expertise, but out of obligation. Each of us must answer the who question, whether thoughtfully or not so thoughtfully. Please accept my reflections on Christian anthropology with ample grace.

Soli Deo Gloria

∞

Heavenly Father,

I believe in Jesus Christ, the son of the living God, who died for our sins and was raised from the dead. Witness to me in my daily life.

Come into my life, help me to renounce and grieve the sin in my life that separates me from you. Define me.

Cleanse me of this sin, renew your Holy Spirit within me so that I will not sin any further. Make me holy.

Bring saints and a faithful church into my life to keep me honest with myself and draw me closer to you. Break any chains that bind me to the past—be they pains or sorrows or grievous temptations, that I might freely welcome God the Father into my life, who through Christ Jesus and the Holy Spirit can bridge any gap and heal any affliction, now and always. Guide me.

Through the power of your Holy Spirit, grant me the strength, grace, and peace to share the Gospel with those around me so your kingdom would come and all might share in its glory together.

In Jesus’ precious name, Amen.

∞

Questions

1. What is anthropology and why is it important?

2. Why is being created in God’s image inconvenient?

3. What is a fundamental principle in human ethics?

4. How would you describe original sin?

5. What is a Gethsemane moment?

Introduction

THE DIVINE IMAGE

And the angel of the LORD appeared to him

in a flame of fire out of the midst of a bush.

He looked, and behold, the bush was burning,

yet it was not consumed.

(Exod 3:2)

The Old Testament offers several glimpses of the divine image. In creation, the image of God’s trinitarian nature underscores the importance of relationship and community. Moses' encounter with God in the burning bush suggests a natural Rorschach test. His time with God on Mount Sinai with the giving of the law provided even more insight into what it means to be created in the image of God.

Trinitarian Creation

Moses is the author of the Books of the Law, also called the Pentateuch (five books), so Moses’ Trinitarian understanding of God in Genesis in the creation accounts informs everything that follows.

God the Father shows up in the first verse of Genesis: “In the beginning, God created the heavens and the earth.” (Gen 1:1) The Holy Spirit shows up in verse two: “And the Spirit of God was hovering over the face of the waters.” (Gen 1:2) Later, in chapter three, we meet a personal God, who walks with us in the Garden. (e.g. Gen 3:9) This is the early image of Christ. Reinforcing the idea of trinity, the primary Hebrew name of God in these accounts, Elohim, appears in the plural.

Being created with our spouse in the image of a Triune God, who is in relationship even within himself, suggests that our own identity is revealed in relationship. In ourselves, we are incomplete and we require community to be whole persons, starting with our spouses. Objections to the concept of the trinity as a late development in the New Testament (e.g. Matt 28:19) are simply uninformed.

The Burning Bush

The burning bush incident poses a naturally random set of patterns suggesting a living analogy to inkblots. A Rorschach test, or inkblot test, provides the psychiatrist insight into a patient’s default assumptions about life because the patient is asked to talk about what is seen in random inkblots. An optimistic, happy person might see sunshine and flowers while a fearful, anxious person might see darkness and monsters.

In Moses’ account in Exodus, we learn that God is present, available, and calling Moses into a relationship and Moses responds to God's call. (Exod 3:4) Where God is, is holy ground (Exod 3:5). When God identifies himself, Moses responds in fear. (Exod 3:6) God reads Moses' deepest desire of his heart and acknowledges the suffering of his people in Egypt. (Exod 3:7) God commissions Moses to deliver the people from Pharaoh. (Exod 3:10) Moses again responds with fear. (Exod 3:11)

God first created in Moses a desire to free his people from bondage and then God called on Moses to honor that desire. While the burning bush served as a Rorschach test, it did not project Moses’ attributes on God. Rather, God used the burning bush to teach Moses about himself, laying bare Moses’ own desires.

This encounter with the burning bush served to call Moses into leadership of the people of Israel, which resulted in the Exodus from Egypt out of slavery and the latter establishment of the Nation of Israel. It is interesting that Moses’ launch into ministry started with a divine encounter and dealing with his own fears and inadequacies.

The Second Giving of the Law

Another important encounter that Moses has with God occurs after the second giving of the Ten Commandments. Moses had an anger management problem that led him to destroy the first set of stone tablets when he descended from Mount Sinai and found the people of Israel worshipping a Golden Calf. (Exod 32:19) God gave Moses a second set of tablets, and when Moses asked to see God’s glory. (Exod 33:18) “The LORD passed before him and proclaimed, the LORD, the LORD, a God merciful and gracious, slow to anger, and abounding in steadfast love and faithfulness.” (Exod 34:6)

The revelation of God’s attributes after the giving of the law suggests a modern parallel. When Congress passes significant legislation, the authorizing committee will publish a conference report to give attorneys and other investigators an interpretative guide should questions arise about the legislation itself. In describing his attributes, God effectively gives us an interpretative guide to the Ten Commandments. These moral attributes also suggest what it means to be created in God’s image.

Exodus as Cautionary Tale

Release from the tyranny of Pharaoh started with the crossing of the Red Sea, a kind of communal baptism, and God’s destruction of the Egyptian army. The exodus from Egypt led to temptations, limits on freedom, and the need to rely on God in order to survive in the wilderness.

Self-reliance under God proved challenging for the people of Israel. Freedom did not mean living with abandon and worshipping idols of our own making. The biblical Golden Calf incident underscored the need for law, which had to be instituted by the sword. (Exod 32:27–28) The forty-year curse incident (Num 14:34) demonstrated the power of fear to hold back those unwilling to trust in God’s promises.

Christians live under grace, but those resisting God remain subject exclusively to law. Even for Christians, the temptations of secular society are real, ever-present, and hard to resist. But we have the image of Christ given in scripture to guide us during trials and tribulations when we have no alternative but to rely on God.

∞

Heavenly Father,

We praise you for being present in our lives, available when we are in need, and call us into relationship.

Forgive us when we remain distant from those around us, hide when others need us, and forgo healthy relationships. Forgive our unwarranted anxieties and fear that keep us from loving those around us.

Thank you for your example of a holy life in Jesus Christ, who loved us enough to sacrifice himself on a cross.

In the power of your Holy Spirit, grant us the courage and strength to be good stewards of the love, life, and resources that you have given us. May we mirror the mercy, grace, patience, love, and faithfulness that we first saw in you.

In Jesus’ precious name, Amen.

∞

Questions

1. What is a Rorschach test and where do we see something similar in the Bible?

2. Why is the Trinity important in understanding the image of God?

3. What is a conference report and where do we see something similar in the Bible?

4. Where did the Israelites learn to rely on God? Where do we?

THE FALL FROM GRACE

Now the serpent was more crafty than any other beast of the field

that the LORD God had made. He said to the woman,

Did God actually say, You shall not eat of any tree in the garden?

(Gen 3:1)

Original sin is introduced in chapter three of Genesis. This conversation begins, not with an explanation of sin, but an alternative to the divine image: the serpent. Adam and Eve are instructed not to eat fruit from the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil. (Gen 2:17) Their freedom extended to all other aspects of life. They do not question God’s authority or even chide at their duty, but they flounder when introduced to someone who does: the serpent.

As postmoderns, we dismiss the personification of evil implied by the serpent without discussion and immediately focus on the first act of disobedience: eating the forbidden fruit.

Conceptual Problems with Original Sin

Our focus on the first act of sin reveals at least three problems. First, the modern preoccupation with original sin limits sin to a single, static act. We then take this conceptualization of sin and debate its reasonableness rather than engaging the text. Second, the context of the immediate text shows intensification of sin over time, but this polluting characteristic of sin is seldom observed or discussed. Third, the introduction of the serpent in the text characterizes sin as rebellion, which is also seldom observed or discussed.

Sin’s dynamic, polluting, and rebellious nature shows up early in the Genesis account. Although Adam and Eve were created in Genesis 1, when God rests on the first Sabbath in Genesis 2 they are not mentioned. (Feinberg 1998, 16) The first sin in scripture is then argued to be a sin of omission (not doing good). It occurred when Adam and Eve refused to participate in Sabbath rest. It was as if God threw a party and they refused to come.

After that, the sin in Genesis escalated from disrespect into open rebellion. In Genesis 3, Adam and Eve commit their first sin of commission (doing evil). In Genesis 4, Cain kills Abel and Lamech takes revenge. In Genesis 5, Noah—which means the man who rested in Hebrew—is born. (Feinberg 1998, 28) In Genesis 6, God tells Noah to build an ark because he planned to send a flood in response to the depth of human corruption and sin. After the flood, only Noah and his family remained, a re-creation event. (Kline 2006, 221–27)

Neglecting sin’s wider context leads us to misunderstand the biblical text, in which sin is pictured as a defining human characteristic.

The Who Question Widens Our Understanding of Sin

The fall from grace is trivialized in characterizing it as a static, one-time event because sin’s dynamic, polluting, and rebellious characteristics are neglected.

If the who question is taken seriously, then the trivialization of the text goes further. Adam’s manhood takes a beating here. What sort of man leaves his wife to contend with a snake? And who does the snake talk to anyway? Eve is also maligned in the text because she first believed the serpent and:

Saw that the tree was good for food, and that it was a delight to the eyes, and that the tree was to be desired to make one wise, she took of its fruit and ate, and she also gave some to her husband who was with her, and he ate. (Gen 3:6)

The text itself makes it easy to believe that the fall from grace occurred because of character deficiencies in both Adam and Eve.

Eager to avoid having to explain these deficiencies in the first family, most postmodern commentators are happy to skip over the who question and debate the reasonableness of a static act of sin. More importantly, focusing on sin as a static act neglects the bigger problem that the who question raises: Sin pollutes our identity and leads us to underestimate the problem of idolatry, which the Bible takes seriously, as suggested by the Second Commandment. (Exod 20:4)

Dynamic Aspects of Sin

The dynamic characteristics of sin deserves further comment. The pollution characteristic of sin occurs because the first act of sin makes the second act easier as we become more callused and develop a taste for sin. An individual sinner may become a serial sinner (the problem of besetting sin), as we see most often in the case of murder and various sexual crimes. However, it can be a problem for any type of sinful behavior.

The cycle of killing and revenge killing is another pattern of communal sin that can only be broken once someone decides to practice forgiveness or enemy love, which is Jesus’ focus.

Moses anticipated one communal pattern of sin in Deuteronomy 30:1–3, the Deuteronomic Cycle cited earlier. You (plural) will sin; be enslaved; and cry out to the Lord. God will send you a deliverer and restore your fortunes. (Brueggemann 2016, 59) This pattern outlines biblical history and with it the rise and fall of nations.

What is interesting about the dynamic aspect of sin is how Jesus deals with it in the Parable of the Prodigal Son. (Luke 15) In the parable, the younger son thinks only of himself in asking for his inheritance and leaving home for a faraway country where he squanders it. What is unique about this story is that the suffering that the young man goes through draws attention to his sin and allows him to see the error of his ways. He grows up and learns to love his father. Unlike Moses’ Deuteronomic Cycle, the cycle of sin is broken and his life transformed.

New Testament Treatment of Sin

The transformation of the Prodigal Son requires us to take sin seriously. When Jesus casts out demons, he clearly takes sin and the who question seriously. (e.g. Mark 5:8) Many commentators quietly scoot past such passages or explain them away as first-century psychology. However, if Jesus is truly divine (characterized as omniscient, omnipresent, and omnipotent), then the New Testament’s confession that Jesus died for our sins must be taken seriously. (e.g. Matt 1:21; 1 Cor 15:3) Otherwise, our sins are not forgiven, our salvation is at risk, and our preaching is in vain. (e.g. 1 Cor 15:14)

Jesus as Denominator

The fall from grace is more important than most postmodern Christians are willing to admit. If we cannot admit our sin, we cannot be forgiven. This is why we must make our faith the number-one priority and focus on the divine image. When Jesus becomes our measure of all things, then with the help of the Holy Spirit, we can recognize and resist evil.

∞

Sovereign Father,

All praise and honor are yours, creator of the universe, who fearlessly creates all things and declares them to be good.

Forgive our disrespect, our intensification of evil, and open rebellion. Lift up the symbol of our rebellion and accept our confession that we might participate in your forgiveness, worship only you, and break the chains of sin that bind us to Satan.

We give thanks for the example of Jesus of Nazareth, who lived a holy life, was crucified for our sin, died on the cross, and was raised from the dead. May we accept his sacrifice and learn from it.

In the power of your Holy Spirit, break the power of sin in our lives that we might be free in Christ to live within your healthy, spiritual boundaries.

In Jesus’ precious name, Amen.

∞

Questions

1. Describe original sin. How does the serpent expand our understanding of sin?

2. How does sin pollute?

3. What makes sin dynamic?

4. What is different about Jesus’ treatment of sin?

ILLUMINATION

And God spoke all these words, saying,

I am the LORD your God, who brought you

out of the land of Egypt,

out of the house of slavery.

(Exod 20:1–2)

The giving of the law occurred in the context of divine disclosure and covenant articulation, which makes the law itself an important extension of the divine image and community identity. Which God? The God who brought you initially out of Egyptian slavery but ultimately brought you out of slavery to sin. Which you? The people of Israel initially but ultimately the people who honor the covenant.

The law itself offers concrete boundaries to the covenant community and, by inference, boundaries to the freedom offered in the Gospel. In this sense, I often refer to the law as to what healthy spiritual boundaries look like from God’s perspective. Outside the faith community, the Ten Commandments appear as a list of dos and don’ts, while inside the community the Commandments simply define who we are: We are the people who honor the commandments.

When Jesus offers the double-love command (love God, love neighbor), the Ten Commandments loom in the background. (Matt 22:36–40) The dichotomy often made between law and Gospel simply disappears. Jesus becomes the more important extension of the divine image.

Law as Image Writ Large