Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Icon Books

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

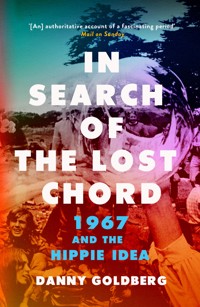

'Danny Goldberg is probably one of the purest, most reasonable guides you could ask for to 1967.' Ex-Rolling Stones manager Andrew Loog Oldham. 'Weaves together rollicking, rousing, wonderfully colourful and disparate narratives to remind us how the energies and aspirations of the counterculture were intertwined with protest and reform … mesmerising.' The Nation It was the year that saw the release of the Beatles' Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band, and of debut albums from the Doors, the Grateful Dead, Jimi Hendrix and Janis Joplin. The year of the Summer of Love and LSD; the Monterey Pop Festival and Black Power; Muhammad Ali's conviction for draft avoidance and Martin Luther King Jr's public opposition to war in Vietnam. On its 50th anniversary, music business veteran Danny Goldberg analyses 1967, looking not only at the political influences, but also the spiritual, musical and psychedelic movements that defined the era, providing a unique perspective on how and why its legacy lives on today. Exhaustively researched and informed by interviews including Allen Ginsberg, Timothy Leary and Gil Scott-Heron, In Search of the Lost Chord is the synthesis of a fascinating and complicated period in our social and countercultural history that was about so much more than sex, drugs and rock n roll.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 456

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

More Critical Praise for Danny Goldberg

for Bumping into Geniuses

“Goldberg reminds us that the recording industry was remade in the late sixties and seventies by businessman-hippies seeking not just profit but proximity to artists they admired and a role in the countercultural ferment. It is one of many insights in this surprisingly excellent book, an engaging, droll, and … largely demystifying look at the evolution of the rock trade from Woodstock to grunge.”

—New York Times Book Review

“An insightful behind-the-scenes view of the music industry from 1969 through 2004 … like having a laminated backstage pass to the music business, intertwined with a juicy slice of countercultural history.”

—Paul Krassner, Los Angeles Times Book Review

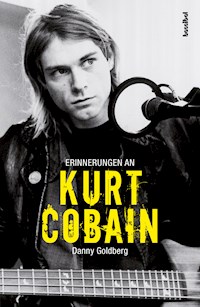

“Danny Goldberg chronicles the phases of his career—rock journalist, record-company president, manager to musicians ranging from Kurt Cobain to Warren Zevon—with the sort of candor few record-biz execs would attempt … Admirably blunt, but also spiked with tart humor.”

—Entertainment Weekly

“A behemoth in the rock and roll industry.”

—Vanity Fair

“Since I first met Danny Goldberg in 1970, he has had an honest relationship with the music business. He believes in the transcendent beauty and power of rock and roll and at the same time has a unique perspective on the business which has presented and preserved it. Danny writes about rock and roll with his characteristic mix of intelligence, reverence, and humor.”

—Patti Smith

“Inside the industry for almost four decades, Goldberg now looks back at those he bumped into during his rise from rock writer to public relations to personal management, plus heading three major record companies … Goldberg summons up some fascinating anecdotes as he writes about these performers with much honesty and compassion, bringing it all back home.”

—Publishers Weekly

“Goldberg tells of his adventures in the music business with insight, humor, and compassion.”

—Seattle Times

for Dispatches from the Culture Wars

“The Democratic Party has two choices: get a clue or die. Danny Goldberg’s new book is a stirring, brilliant, last-chance plea to Democrats that if they are unwilling to do their job—be a voice for working people, young people, women, the elderly, the poor, and people of color (in other words, from the MAJORITY of the country)—then their days as a party are numbered. Years from now, if the Democrats have long faded from American memory, anthropologists and historians will ask, Didn’t any of them read this book by Danny Goldberg?”

—Michael Moore

“Goldberg authoritatively dissects the disconnect between progressive politics and younger voters.”

—Time Out New York

“An affecting memoir of Goldberg’s experiences within the clash of popular culture and politics … The great value of his book is as an insider’s tour of American cultural life from the sixties to the present.”

—Library Journal

“Danny Goldberg’s searing insights and straightforward recommendations for the future of the left should be required reading for anyone concerned with the state of democratic politics in this country. This book exemplifies the notion that the pen truly is mightier than the sword.”

—Reverend Jesse L. Jackson Sr.

“Rock, rap, reactionaries, and liberals all get a thrashing in Goldberg’s insightful Dispatches from the Culture Wars.”

—Vanity Fair

“Lively and intelligent … Goldberg reminds us once again how the battle for freedom of expression needs to be refought every day.”

—Eric Alterman

“Danny Goldberg’s memoir contains the powerful reflections of the most progressive activist in the recording industry. His candor, vision, and sense of humor are infectious.”

—Cornel West

“If Lester Bangs and Maureen Dowd had a love child, he’d have written this book.”

—Arianna Huffington

For Paul Krassner, Wavy Gravy, and Ram Dass

TABLE OF CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

“There is a mysterious cycle in human events,” my parents’ idol Franklin Delano Roosevelt proclaimed in the speech in which he also said that their generation had a “rendezvous with destiny.” The mystery that informed my own adult life revolves around a different rendezvous several decades after Roosevelt’s speech. I was sixteen and wide-eyed and there really was a moment when “peace and love” was not meant or taken ironically. In terms of mass popular American culture, that moment peaked in 1967. Where did it come from? Where did it go?

The hippie movement that swept through the Western world was like a galloping horse in the wild. A few dozen people were able to ride it for a while, some even steering it for a brief period, but no one—no philosopher, no spiritual figure, no dope dealer, no songwriter or artist, and certainly no political leader—ever controlled it. It was the original “open source.” From the influence of psychedelics to a widespread rebellious ethos that resisted any kind of authority within various countercultures, the era can only be understood through a collection of disparate, sometimes contradictory narratives.

David Crosby, Paul Kantner, and Robin Williams are among those who have been credited with the saying, “If you remember the sixties, then you weren’t really there.” The quote is usually deployed as a laugh line, as if anyone truly immersed in hippie culture would have been so stoned that they would have forgotten it all.

On the other hand, perhaps some chose not to talk about certain nuances that seemed too fragile to survive in the public air. In The Varieties of Religious Experience, William James suggests that one quality of a mystical experience is the impossibility of describing it. Yet hints can be found.

“The sixties” is a hybrid of the civil rights and antiwar movements combined with a mystical spirit that worked through some extremely fallible humans. Allen Cohen, a founder and editor of the San Francisco countercultural newspaper the Oracle, referred to hippies as “a prophetic community.” But they were not, for the most part, formally religious or even well behaved. There is no doctrine, just thousands of stories, and a lingering vibe.

I graduated from Fieldston High School in New York City in 1967, and the sixties had a lasting influence on me and many of my closest friends from that time. I attended the University of California, Berkeley, briefly (very briefly), and by the end of 1968 had begun my career in the rock-and-roll business, an industry that itself owes much of its success to sixties culture.

I refer to a “lost chord” in the title of this book because whatever “it” was in 1967 was the result of dozens of separate, sometimes contradictory “notes” from an assortment of political, spiritual, chemical, demographic, historical, and media influences that collectively created a unique energy. It should go without saying that no two people perceived the late sixties in the same way, and that the space limitations of a single volume and my own myopia require me to leave out far more than I include.

This is a subjective and highly selective history, an attempt at trying to remember the culture that mesmerized me, to visit the places and conversations I was not cool enough to have been a part of.

My perspective is that of a straight white male New Yorker from a mostly secular Jewish family. I did very little research on countercultural developments outside of London, California, and New York, the places that fired my imagination at the time. I had little awareness of many vibrant cultural spheres including art, literature, and fashion, limitations that are obvious in my narrative.

Political struggles both on the street and in the corridors of government were central to the era. However, I disagree with numerous left-wing historians who view the “hippie” phenomenon as a secondary sideshow revolving around escapism that did more harm than good to what they regard as the “serious” aspects of the sixties. This conventional lefty wisdom ignores the mystical aspects of the counterculture that were intertwined with protest and reform.

Yet, even though many of us were a lot more into LSD than SDS (Students for a Democratic Society), the overwhelming shadow of the military draft affected tens of millions of young men and their families. There was a widespread loss of faith in authorities who advocated obedience to a Cold War foreign policy. The cauldron of social readjustments for both blacks and whites in the wake of a long overdue dismantling of racist Jim Crow laws was intense. (Needless to say, many Americans of other ethnicities, including Latinos, Native Americans, and Asians, had their own challenges and journeys, but in the cultures of 1967 that reached my teenage brain it was the black/white relationship that predominated.)

The lost chord I am seeking had many other notes in it as well. After all, men in the United Kingdom were not called upon to fight in Vietnam; notwithstanding its colonial karma, the UK did not have racial tensions comparable to America’s. Yet there is no version of “the sixties” in which British rockers like the Beatles, Cream, and Donovan, radical therapists like R.D. Laing, writers like Bertrand Russell, and fashion icons like Mary Quant, were not integral figures. Millions of European, Australian, Canadian, and American teenagers felt they had more in common with each other than they did with anyone else.

In talking to dozens of people of my generation who were affected by the hippie idea, there is a near universal recollection of a period of communal sweetness. There was an instant sense of tribal intimacy one could have even with a stranger. The word that many used was “agape,” the Greek term that distinguishes universal love from interpersonal love.

One personal story I like to tell about the sixties took place in the San Francisco airport in 1967 when I was trying to get on a plane back to New York to see my family for Thanksgiving. I was barefoot and was told by an unpleasant airline employee that I could not board without shoes. With little time to spare, I scanned the airport and made a beeline toward a young guy with long hair who looked cool to me. I explained my predicament and asked if he would lend me his shoes for the flight, and gratefully accepted them when he agreed without a moment’s hesitation. I am still not sure what is more remarkable, the fact that he gave his shoes to a stranger or that I had the certainty that he would do so. I am equally certain that this would not have been possible a year later.

The word “hippie” morphed from a brief source of tribal pride to a cartoon almost immediately. Ronald Reagan, who began his first term as governor of California in 1967, said, “A hippie is someone who looks like Tarzan, walks like Jane, and smells like Cheetah.”

Most of the mainstream liberal establishment of the time was almost as dismissive. In August of 1967, Harry Reasoner delivered a report for the CBS Evening News in which he referred to the Haight-Ashbury section of San Francisco as “ground zero of the hippie movement.” After an interview with members of the Grateful Dead, Reasoner questioned the premise that hippies were doing anything to make the world a better place: “They, at their best, are trying for a kind of group sainthood, and saints running in groups are likely to be ludicrous. They depend on hallucination for their philosophy. This is not a new idea, and it has never worked. And finally, they offer a spurious attraction of the young, a corruption of the idea of innocence. Nothing in the world is as appealing as real innocence, but it is by definition a quality of childhood. People who can grow beards and make love are supposed to move from innocence to wisdom.”

A similar disdain was prevalent in most liberal circles in Washington. After Timothy Leary and Allen Ginsberg testified in front of the US Senate Subcommittee on Juvenile Delinquency, Thomas Dodd, the Democratic committee chair, denounced them as “pseudo-intellectuals who advocate the use of drugs in search for some imaginary freedoms of the mind and in search of higher psychic experiences.”

Fifty years later, reading those sanctimonious put-downs reminds me of the revulsion I had for such “respectable” men. For many of us, the idea of breaking the addiction to climbing the ladder of officially sanctioned “success” was not an “imaginary freedom” but a reason to live. None of us felt, individually, that we were “saints,” but we did believe that there was a growing subculture that could come up with a better value system than the one we were born into. We didn’t see “innocence” and “wisdom” as mutually exclusive, and we bitterly resented it when unhappy authority figures insisted on this false choice.

There was indeed a danger from indiscriminately using hallucinogens, but we also knew that for most people they were nowhere near as dangerous as the corrosive effects of legal drugs like beer, and gin and tonics, or tranquilizers like Librium, which were inexplicably accepted by many of the same people who were so down on pot and acid—the criminalization of which further eroded the credibility of their authority for many of us.

As for Senator Dodd’s condescending use of the word “pseudo-intellectuals,” he was among the majority of Democrats who sided with the supposedly wise Ivy League “intellectuals” in the Kennedy and Johnson administrations who were responsible for the escalation of the Vietnam War.

I first used the phrase “the hippie idea” after Gil Scott-Heron died. Gil was one of the great R&B/jazz poets of the seventies and eighties and considered one of the progenitors of hip-hop. But I first met him in 1964 when we were in the same tenth-grade English class. Gil’s mother was strict enough that he wasn’t taking acid with us in high school. A lot of his identity in those days revolved around being a jock—the center on the basketball team and a wide receiver on the football team.

But Gil also befriended “heads” like me and breathed the air of the hippie idea along with the rest of us. (A “head” was someone who smoked dope. “Straight” in the pre–gay liberation era meant someone who didn’t get high.) Gil joined several pickup rock bands and sang contemporary hits like “Wooly Bully” and “Like a Rolling Stone.” He was always up for a conversation about the meaning of life and already had the seeds of a leftist radical critique of racism and the ugly side of capitalism that would inform his extraordinary body of work. Shortly after we graduated, Gil released the classic song “The Revolution Will Not Be Televised.” For decades the song was used in film montages of protests and riots. Yet a year before he died, Gil did an interview where he sardonically explained that the lyrics were often misunderstood: “It meant that the revolution is inside you.” (As this book was being written, the song was repurposed over the opening credits in the sixth season of the Showtime series Homeland.)

What I mean by “the hippie idea” is the internal essence of the tribal feeling separate and apart from the external symbols which soon became overused, distorted, co-opted, and thus, understandably, satirized. The conceit is that if you subtract long hair, hip language, tie-dyed clothing, beads, buttons, music, demonstrations, and even drugs, there was still a distinctive notion of what it meant to be a happy and good person, and a sense of connection to others was the invisible force behind those things. It included the moral imperative to fight for civil rights and against the war, and the spiritual notion that there were deeper values than fame and fortune. Peace and love.

The derisive term for what one didn’t like was “plastic.” At the same time, the hippie idea was also a joyous contrast to pessimistic postwar existentialists and Marxist intellectuals. They wore black. Hippies liked colors.

To some, the counterculture offered an alternative to organized religions that too often seemed preoccupied with rules and conformity, especially on sexual matters. (One reason Eastern religious traditions resonated with many hippies was because they carried no American family baggage.) But for millions like me, it was a deeply felt rejection of the secular religion of fifties and early sixties America: Mad Men materialism, along with Ayn Rand’s social Darwinism and, to some extent, the Freudian doctrine that reinforced it. Much of the “established” world seemed removed from the deepest aspects of human consciousness.

Martin Luther King Jr.’s devotion to Christianity, Muhammad Ali’s commitment to Islam, Timothy Leary’s reverence for The Tibetan Book of the Dead, the connection to Buddhism and Hinduism that inspired Allen Ginsberg and many of the other beats, the fascination of the Beatles with meditation and the Hare Krishna movement, the metaphysical metaphors in many Bob Dylan songs, the guitar solos of Jimi Hendrix, the ripple effect of John Coltrane, and millions of individual psychedelic experiences framed the counterculture of the sixties with a level of mysticism far more intense and meaningful than had been prevalent in the previous postwar era. (Atheists and agnostics fit right into the hippie idea as long as they were cool. As Grateful Dead manager Rock Scully said, the Dead had one cardinal rule: “Do not impose your trip on anyone else.”)

American bohemianism went back at least as far as Emerson and the transcendentalists and reemerged in the fifties in beatnik literature, a few anarchic comedians, and the folk and jazz scenes. But these were all marginalized subcultures, dwarfed in most of America by network TV, pop radio, sports, advertising, money, and mainstream religion.

The distinguishing characteristic of the sixties that emerged after the assassination of President Kennedy was that ideas which had previously been quarantined to a few avant-garde enclaves and ghettos now collided with a giant and prosperous “baby boomer” generation. Allen Ginsberg said that when he heard Bob Dylan’s song “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall,” he wept, because the bohemian torch of illumination and self-empowerment had been passed on to a new generation.

In 1967, previously esoteric ideas burst briefly into the center of mass culture, influencing the thoughts of millions more people than any American counterculture before or since. Changes in the technology of stereo recordings (and a newly portable ability to hear them), FM radio, and the mimeograph machine fostered “underground” media at an unprecedented level. The sheer magnitude of the baby boomer generation, coupled with advertisers’ hunger for the young demographic, created a climate of mainstream media in which the counterculture made good copy and got high ratings.

1967 was the year of Be-Ins and the Summer of Love, when tens of thousands of teenagers flocked to the small hippie neighborhood of Haight-Ashbury in San Francisco. LSD had been made illegal in California in October 1966, with the rest of the country soon to follow. The antidrug laws, like other forms of prohibition, immediately increased the demand and use of acid, dwarfing the previous interest in and availability of it.

1967 was the year of the Monterey International Pop Festival, which introduced Jimi Hendrix, Otis Redding, Ravi Shankar, and Janis Joplin to a big American rock audience. Hendrix, Joplin (as part of Big Brother and the Holding Company), Pink Floyd, the Velvet Underground, Country Joe and the Fish, the Doors, the Grateful Dead, and Sly & the Family Stone all released their debut albums that year. Among the year’s classic singles were Van Morrison’s “Brown Eyed Girl,” the Turtles’ “Happy Together,” Procol Harum’s “A Whiter Shade of Pale,” Scott McKenzie’s “San Francisco (Be Sure to Wear Some Flowers in Your Hair),” and the Youngbloods’ hit version of “Get Together” with the chorus, “Come on people now, smile on your brother, everybody get together, try to love one another right now.”

It was also the year in which the Beatles released the singles “All You Need Is Love” (introduced via the world’s first global satellite TV transmission) and “Strawberry Fields Forever,” in addition to the album Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. Rolling Stone began publishing in 1967 and “underground rock radio” started broadcasting.

Rhythm and blues (increasingly called “soul music”) was growing on a parallel track through the minds of geniuses like Smokey Robinson, Marvin Gaye, and Aretha Franklin, while at the same time there was a cluster of jazz musicians who dove into the hippie ocean and greatly affected it, including Ornette Coleman, Sun Ra, and Pharoah Sanders.

It was the year that Richard Alpert, who had helped popularize LSD, first went to India, met his guru, and was renamed Ram Dass. It was also the year that the Beatles met the Maharishi, putting the word “meditation” on the front pages of newspapers around the world.

Many pivotal political moments took place in 1967. In the spring, Muhammad Ali refused induction into the army, and Martin Luther King Jr. parted company with mainstream civil rights leaders and publicly denounced the Vietnam War.

In October there was an antiwar march in Washington in which some hippies fancifully insisted they would levitate the Pentagon. That same month, Huey P. Newton got arrested for murder in Oakland, elevating the Black Panther leader to international celebrity status. Stokely Carmichael and Charles V. Hamilton published Black Power. The summer produced the worst race riots in American cities since the Civil War. (The word “riot” itself was, and remains, a source of controversy. Many activists prefer “revolt” or “rebellion.”)

1967 was to be the last full year of power for Lyndon B. Johnson. Allard K. Lowenstein searched for an antiwar Democrat to run against Johnson, and Senator Eugene McCarthy stepped into that role. Che Guevara was killed in Bolivia and overnight became a left-wing icon. Israel won the Six-Day War.

Yet, for all that happened in this pivotal year, my focus is on the feeling, not on the calendar, and there are moments integral to the story that occurred both before and after 1967. Nevertheless, 1968, taken as a whole, was much darker—Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert Kennedy (who joined the presidential race early in the year) were both assassinated, and that year’s primary political legacy was the violent police reaction to protests outside of the Democratic National Convention, and the subsequent election of Richard Nixon.

Forces in the government and corporate America conspired to crush the cultural rebellions, but they were aided by infighting on the political left, a syndrome which, legend has it, led Che Guevara to quip that if you asked American leftists to form a firing squad, they’d get into a circle.

Hubris and/or paranoia distorted the behavior of would-be leaders, while in many corners of the subculture there developed smug, hip parochialism that grew rancid over time. Too often, “heads” looked down on “straights,” which caused more polarization than brotherhood.

By 1968, heroin and speed were ubiquitous in hippie culture. An assortment of lowlife parasites rushed in to exploit the explosive hippie scene and virtually erased the fragile, intense meaning the word “hippie” had embodied just a year earlier. Undercover FBI agents could grow their hair long and wear brightly colored clothes.

The market for products that hippies liked created a class of hip capitalists who had varying degrees of commitment to ethical and spiritual ideals. The shallower aspects of Hollywood started to take their toll. Words like “cool” and “groovy” and sitar riffs could all be dumbed down to support sitcom gags and could be appropriated by superficial bullshit artists.

As the decades passed, the music of the period would prove to be the most resilient trigger of authentic memories, but even some of the songs of the era were gradually drained of meaning by repetitive use in TV shows, movies, and commercials, all trying to leverage nostalgia. Nostalgia for what?

The efforts of millions of peace activists were sometimes overshadowed by the destructive, violent acts of a few dozen delusional radicals. An earnest spiritual movement became obscured to most observers by stoned, pontificating buffoons. No wonder the punk movement that began in the midseventies detested the cartoon distortion of hippies.

Even so, every other belief system has had its pretenders. If one extends the religious metaphor to the hippie idea, it’s not really surprising that its existence didn’t eliminate most of the darkness of the world. Neither did Christianity nor the Enlightenment. But the counterculture did broaden the idea of what it is to be a human being in the Western world.

There is a direct line from many of the leaders of 1967 to contemporary figures such as Steve Jobs, Mark Zuckerberg, Bernie Sanders, Judd Apatow, and Oprah Winfrey, all of whom acknowledge important influences from the figures I am writing about. The environmental movement, which is a direct offshoot of hippie ideas, continues to be a major social force, and “mindfulness” and yoga are even more prevalent in the United States of 2017 than veggie burgers.

Researching 1967 has been a roller coaster ride for me. Sometimes it rekindles the “lost chord” and inspires me. At other moments I yearn to go back in time and warn my heroes that they are about to walk down a path they will regret.

As I explored the forgotten intricacies of 1967, the hippie idea that entranced me as a teenager still seems like an alchemy that produced something unique and special out of the energies and aspirations of dozens of disparate, intense, and cantankerous people, many of them deeply damaged, all of them in one way or another very far out.

That line—if you remember the sixties, you weren’t really there—does have some truth to it. In addition to hallucinogens, the drug of fame often led to fanciful mythmaking. Some stories have been repeated so many times that they have taken on a life of their own. Even close friends have different versions of well-known events. The underground press, whose writers were often the only public witnesses to countercultural activities, had little or no fact-checking capabilities. I have done my best to get it right, but apologize in advance for any faulty assumptions.

Examined up close, there were dozens of separate subcultures, each of which felt it owned the late sixties. San Francisco and Los Angeles rock-and-roll people were deeply suspicious of each other. The Beatles lived in their own world. New York hip life was more intellectual. Black nationalism, the nonviolent civil rights movement led by Dr. King, Muhammad Ali, and the Nation of Islam had fierce disagreements with each other, and they all had different views of the antiwar movement. Student radicals, the old left, liberal antiwar Democrats like Bobby Kennedy and Gene McCarthy, and anarchists often detested each other. Beatniks, psychedelic evangelists, and mystics were often on separate planets.

Yet to many teenagers at the time, this collection of energies somehow harmonized and created a single feeling, the lost chord that lasted briefly, but penetrated deeply into the minds and hearts of those who could hear it. I admired something about all of them. I never felt aligned with just one faction but with the ephemeral collective vibe that permeated the culture. Time was so compressed that many of the signature events of 1967 happened within hours or days of each other. Often they were intertwined. My fascination is with the whole, not merely its parts. However, if I could time travel back to 1967, there is no question that I would begin in the Haight-Ashbury section of San Francisco.

CHAPTER 1

BEING IN

The precursor to the brief cycle in which Haight-Ashbury was the biggest counterculture magnet in the Western world is generally thought to have begun in the summer of 1965 at the Red Dog Saloon in Virginia City, Nevada—just across the border from Northern California—where a rock band called the Charlatans played for several months. They took a lot of acid and created some of the first light shows and psychedelic concert posters. They wore Edwardian clothing, conveyed a weird nostalgia for idealized prenuclear America, and revered Native Americans. Although the Charlatans never developed the national following of other San Francisco bands, they were integral to many of the big rock events in the Bay Area in the late sixties. (Dan Hicks of the Charlatans would go on to form Dan Hicks & His Hot Licks.)

By the end of 1965, the Charlatans had moved to the racially integrated Haight-Ashbury neighborhood of San Francisco. It was near several university campuses and had become a center for artists, beatniks, and other bohemians, primarily because of its cheap rents. There were many large Victorian houses, which had up to six bedrooms and cost as little as $120 a month. By the end of 1966, the twenty-five square blocks had a distinctive culture. One could see mandalas made of yarn and drawings from Native American and Eastern religious traditions in many windows. A group of merchants with names like God’s Eye Ice Cream and Pizza Parlor had sprung up to service the new residents. Members of the new psychedelic rock bands Jefferson Airplane, the Grateful Dead, and Big Brother and the Holding Company all moved into the neighborhood.

On January 3, 1966, the Psychedelic Shop opened on 1535 Haight Street, signaling a turning point in the growth of the area as a countercultural center. The store sold books on Eastern religion and the occult, records of Indian music, beads, incense, posters, pipes, and other paraphernalia. It would be the prototype for hundreds of “head shops” that would open up across America in the coming years. A couple of weeks later, the Trips Festival attracted what was at the time a staggeringly high number of people—six thousand over the course of a weekend—to the Longshoreman’s Hall in San Francisco. Many of the attendees drank fruit punch spiked with LSD while watching performances by popular local bands.

By the end of the summer of 1966, several thousand hippies were living in the Haight, and in the fall a new publication called the San Francisco Oracle appeared. During its brief but glorious eighteen months of existence, the Oracle was as definitive a document as would ever exist of the messianic aspirations of the Haight-Ashbury scene. (Tattered individual copies regularly sell for hundreds of dollars on eBay.) The paper was conceived by editor Allen Cohen and art director Michael Bowen. Cohen said he had a dream of a newspaper with rainbows on it that was read all over the world. Both of the Oracle founders were acidheads. Cohen sold some of famed LSD maker Augustus Owsley Stanley III’s earliest tablets, and Bowen had been arrested with LSD pioneer Timothy Leary in Millbrook, New York.

The initial $500 investment for the Oracle came from Ron Thelin, who ran the Psychedelic Shop with his brother Jay. The Oracle featured brightly colored psychedelic art and essays by and about counterculture luminaries. In its first issue it had a manifesto with a founding-fathers-on-acid declaration: “When in the course of human events it becomes necessary for people to cease [obeying] obsolete social patterns which have isolated man from his consciousness … we the citizens of the earth declare our love and compassion for all hate-carrying men and women.”

The Oracle regularly printed articles by and interviews with luminaries like Allen Ginsberg, Gary Snyder, Alan Watts, Richard Alpert, and Timothy Leary. Within a few months the Oracle could be found in nascent hip communities in every region of the United States and many other parts of the world. With typical grandiosity Leary stated, “If the Buddha were alive, he would read the Oracle.”

However, the Oracle did not speak for most political radicals and it certainly did not represent the vibe of the Diggers, an American collective who took their name from a group of seventeenth-century British radicals opposed to the Church of England and the British Crown.

The sixties Diggers delighted in tormenting brothers and sisters in the hippie and radical political communities for being insufficiently pure. The Diggers did not believe in money or any external measure of accomplishment. They berated head shop owners, concert promoters, and others in San Francisco who made money from the culture, and they detested media coverage of the scene.

The Diggers had emerged from the avant-garde San Francisco Mime Troupe and were more about performance art than politics. On the streets of Haight-Ashbury, the Diggers sometimes wore animal masks, held up traffic, passed out joints to people on the street, and gave away fake dollar bills printed with winged penises. They also organized a lot of the free concerts that helped cohere the Haight-Ashbury community. They got ahold of a mimeograph machine and began printing and distributing a newsletter under the name the Communication Company. One of their flyers read: “To show Love is to fail. To love to fail is the Ideology of Failure. Show Love. Do your thing. Do it for FREE. Do it for Love. We can’t fail.”

The Diggers also felt a moral imperative to address the day-to-day realities of poor people. They made “Digger stew” from day-old food gathered from local markets and gave away hundreds of meals a week. They also briefly operated a “free store” in Haight-Ashbury that gave away donated clothing.

Emmett Grogan of the Diggers was an intense twenty-four-year-old from Brooklyn with movie-star good looks and a fierce vision of cultural revolution. In his memoir Ringolevio, Grogan expressed Digger thinking at the time, railing against “the pansyness of the SF Oracle underground newspaper, and the way it catered to the new, hip, moneyed class by refusing to reveal the overall grime of Haight-Ashbury reality.” He detested the “absolute bullshit implicit in the psychedelic transcendentalism promoted by the self-proclaimed, media-fabricated shamans who espoused the turn-on, tune-in, drop-out, jerk-off ideology of Leary and Alpert.” Grogan wrote that he “immediately dismissed as ridiculous the notion that everything would be all right when everyone turned on to acid.”

The other best-known Digger was the twenty-five-year-old Peter Cohon, who would soon change his name to Peter Coyote and in the decades that followed have a successful career as an actor in dozens of Hollywood films including E.T.

One person who was equally at home in the worlds of the beatniks, radicals, acidheads, and rock and roll was Allen Ginsberg. In addition to his explorations of psychedelics, he was an unrelenting critic of militarism. In 1966, he wrote a poem called “Wichita Vortex Sutra,” which mocked Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara, who had described one of his errors in escalating the war in Vietnam as a “bad guess.” The poem included some of the very few public references to the allegedly closeted homosexuality of J. Edgar Hoover and Cardinal Spellman of New York, who was also one of the biggest cheerleaders for the war in Vietnam: “How big is Cardinal Vietnam? / How little the prince of the FBI, unmarried all these years!”

I worked with Ginsberg on his last recordings in the early nineties and asked him if he knew that Hoover was gay. The poet nodded. Why had he not been more outspoken about Hoover’s sexuality at a time when the FBI director was wreaking havoc on the lives of so many decent people? Ginsberg told me he had a friend when he was a college student at Columbia who regularly had sex with Cardinal Spellman and who asked the prelate if he weren’t worried that his career would be ruined if his propensity for having sex with young men was ever made public. Spellman supposedly laughed and said defiantly, “Who would believe it?” Ginsberg explained to me that in the context of the repressive power of the establishment at the time, the words of the poem were as far as he felt he could safely go.

“Wichita Vortex Sutra” also made clear Ginsberg’s antipathy to Soviet-style communism, which, among its many moral shortcomings, was repressive in the arts.

Black Magic language,

formulas for reality—

Communism is a 9 letter word

used by inferior magicians

the wrong alchemical formula for transforming earth into gold

With his black horn-rimmed glasses, long black beard, and white Indian shirt, Ginsberg, despite being forty years old at a moment when youth was ascendant, was one of the most recognizable figures of the counterculture. Although he was often profane, was openly gay, and was an unapologetic left-winger, Ginsberg’s literary brilliance and flair for self-promotion had propelled him to a level of celebrity rarely found in bohemian history. Unique among the beat writers, Ginsberg had embraced sixties rock and roll and the hippie culture. He had taken LSD with Tim Leary and Ken Kesey, and had been befriended by the Beatles and Bob Dylan.

Known primarily for poetry, advocacy of free speech in the arts, and mysticism, Ginsberg was also a peace activist and had withheld a percentage of his taxes as a form of protest against the war. The IRS notified him at some point that they would seize $182.71 from his Howl and Other Poems royalties, which, among other things, was a testament to how little compensation there was in being America’s most famous poet.

When the editors of the Oracle wanted to get the counterculture to the next level in early 1967, Allen Ginsberg was the indispensable man to help them do so.

GATHERING OF THE TRIBES

Ginsberg would later say that the Be-In in San Francisco in early 1967 was “the last purely idealistic hippie event,” but at the time the notion that the spiral of sixties countercultural growth and euphoria was peaking would have seemed absurd to those involved. There were more “heads” every single day.

Organizing an event with self-proclaimed revolutionaries, radicals, and cosmic explorers had not been easy. The very term “Be-In” was a mocking hippie twist on the civil rights movement’s term “sit-in” and the Vietnam War protest’s “teach-in.” The phrase was also a pun—another way of saying “being,” as in “human being.” (Like much hip language, the device had a short shelf life before going mainstream. An NBC network prime-time comedy show called Rowan & Martin’s Laugh-In would debut in September 1968.)

There were intense factions whose conflicts with each other were at the center of day-to-day life at the center of the hippie storm. Hence the subtitle of the 1967 San Francisco Be-In: “A Gathering of the Tribes.” Tribes, plural.

The Be-In sprang from the minds of the Oracle’s Allen Cohen and Michael Bowen. Cohen saw the counterculture in glorious terms. Years later he would write, “The beat and hippie movements brought the values and experiences of an anarchistic, artistic subculture, and a secret and ancient tradition of transcendental and esoteric knowledge and experience, into the mainstream of cultural awareness … [It] gave us back a sense of being the originators of our lives and social forms, instead of hapless robot receptors of a dull and determined conformity.”

A few months earlier, a police shooting of a black youth on September 27, 1966, led to riots in the Hunters Point neighborhood and a curfew was imposed in San Francisco. Bowen put up posters telling hippies to stay inside. Emmett Grogan, on the other hand, posted signs saying, Disobey the Fascist Curfew. Each took down the other’s signs. The two men ran into each other at a telephone pole, and they began an argument which would persist throughout 1967.

“The Diggers were … passionately critical of the commercialization of the Haight,” wrote Cohen. “Generally, the atmosphere around the Diggers was desperate, dark, and tense, while at the ordinary hippie pad, it was light, meditative, and creative, with a mixture of rock and raga music, Oriental aesthetics, and vegetarian food.” Maybe so, but at their peak the Diggers were providing five hundred free meals a week to people in the community, which brought them a lot of credibility on the street.

If Cohen and Bowen were going to be successful in pulling off the Be-In as a true “gathering,” they needed to avoid a torrent of negativity from the Diggers, who initially saw it as a gimmick created by an organization of head shops and a loose conglomeration of “hip stores” called the Haight Independent Proprietors (HIP). The Diggers were suspicious that HIP was hoping to attract national publicity so that they could sell “hippie products” to chain stores and at the same time attract more tourists to Haight-Ashbury.

While it’s impossible to know the inner motivation of every Haight merchant of the time, the Digger theory does seem to have been an unfair characterization of Ron Thelin, whose shop was part of HIP. Thelin soon thereafter told the Oracle, “The direction I see it taking is getting back to the land and finding out how to take care of ourselves, how to survive, how to live off the land, how to make our own clothes, grow our own food, how to live in a tribal unit.” (In October 1967 the Psychedelic Store would close and Thelin would move to Marin County, where for the rest of his life he worked as a cab driver, a mason, and a carpenter.) At the Oracle, Cohen and his colleagues lived hand-to-mouth and avoided the kinds of tabloid stories that drove up the circulation of typical “underground” newspapers; they rejected sleazy ads as well.

Cohen got HIP to agree that Haight stores would all be closed on the day of the Be-In so at least there wouldn’t be immediate profit from those who came in the name of idealism. The Diggers scored an additional agreement with a different kind of capitalist, Augustus Owsley Stanley III (known mostly as “Owsley” or his nickname “Bear”), who agreed to give three hundred thousand tablets of “White Lightning” LSD to the Diggers to distribute free to attendees of the Be-In. Owsley also provided the seventy-five turkeys from which free sandwiches would be made. Although Grogan would later mock the spiritual aspirations of the Be-In, the Diggers stuck to a commitment not to bad-mouth it beforehand.

Cohen also had to reassure the San Francisco rock musicians who had emerged as key thought leaders in the community. The musicians were a generation younger than the beatniks. Bob Weir of the Grateful Dead was nineteen; Janis Joplin was twenty-three; Jerry Garcia and Marty Balin were twenty-four; Jefferson Airplane’s new singer, Grace Slick, was twenty-seven. The Airplane, the Dead, and Joplin all had houses in the Haight within a few blocks of each other. Their primary concern was maintaining a vibe that fostered creativity.

British folk-rock singer Donovan had followed in Bob Dylan’s footsteps and had gone electric in 1966 with the album Sunshine Superman, which included the song “The Fat Angel,” the chorus of which paid homage to the Haight rockers: “FlyJefferson Airplane, gets you there on time.” The Airplane was the first local band to get a record deal (with RCA). Grace Slick had not been a member on their first album but joined in late 1966. Two songs on which she sang lead on the band’s second album, “Somebody to Love” and “White Rabbit” (which she also wrote), both became massive hits in 1967, the first emanations of the Haight culture to go mainstream.

Yet another “tribe” in the counterculture who initially resisted participation in the Be-In were the Berkeley radicals who by 1967 were primarily focusing on trying to end the Vietnam War. The weekly underground paper across the Bay, the Berkeley Barb, centered far more on radical politics and far less on spirituality than the Oracle.

Cohen explained, “Bowen and I had become concerned about the philosophical split that was developing in the youth movement. The antiwar and free-speech movement in Berkeley thought the hippies were too disengaged and spaced out, and that their influence might draw the young away from resistance to the war. The hippies thought the movement was doomed to endless confrontations with the establishment that would recoil with violence and fascism … In order to have a Human Be-In, we would have to have a powwow.”

The meeting took place at Bowen’s pad at the corner of Haight and Masonic. The Berkeley radical contingent included Max Scherr, who was the publisher of the Berkeley Barb, and antiwar activists Michael Lerner and Jerry Rubin. Rubin was a twenty-eight-year-old native of Cincinnati who had enrolled in the University of California, Berkeley, in time to witness the Free Speech Movement in 1964. Later that year he was among a group of American students who traveled illegally to Cuba and met with Che Guevara. In 1965, he was one of the organizers of the Vietnam Day Committee—a small group who tried to block trains filled with GIs who were ultimately headed for Vietnam. Rubin and fellow radicals Mario Savio and Stew Albert served short jail sentences after being convicted of “public nuisance.”

Rubin and his girlfriend Nancy Kurshan had recently met with then-unknown Eldridge Cleaver, who had been released from prison in late 1966 and would soon join the Black Panther Party, eventually becoming their Minister of Information. In an introduction to Rubin’s book Do It! Cleaver recalled, “Thinking back to that evening in Stew’s pad in Berkeley, I remember the huge poster of W.C. Fields on the ceiling, and the poster of Che on the wall … This was our first meeting. We turned on and talked about the future.” Now the question was whether Rubin could relate equally well to the San Francisco hippies.

While Rubin tried to soak up the hippie ethos, his comrade Michael Lerner earnestly asked the group, “What are your demands?” The hippies and musicians were amused. “Man, there are no demands! It’s a fucking Be-In!” Still, it was agreed that Rubin could make a short speech.

Ginsberg said that the Be-In would be “a gathering together of younger people aware of the planetary fate that we are all sitting in the middle of, imbued with a new consciousness, and desiring of a new kind of society involving prayer, music, and spiritual life together rather than competition, acquisition, and war.”

Bowen and Cohen consulted Gavin Arthur, a philosopher and astrologer who was the grandson of US President Chester Arthur. According to Gene Anthony’s The Summer of Love, Arthur said that January 14 was the day “when communication and society would be most favored for a meld of positive communication for the greatest good.” He also claimed it was “a time when the population of the earth would be equivalent in number to the total of all the dead in human history.”

The Oracle cover story about the upcoming Be-In said, “A new nation has grown inside the robot flesh of the old … Hang your fear at the door and join the future. If you do not believe, please wipe your eyes and see.” The issue featured a centerfold with an ornate trippy drawing by Rick Griffin in which the faces of ancient mystics emerged from hookahs. In its center was a heart-shaped depiction of a lecture Ginsberg had given to Unitarian ministers in Boston the previous November called “Renaissance or Die,” in which he associated his philosophy with that of Thoreau and Emerson and then urged everyone over the age of fourteen to try LSD at least once. The Barb also ran an announcement on their front page.

A poster designed by psychedelic artist Stanley Mouse was put up in Marin County, Berkeley, and the Peninsula, as well as around Haight-Ashbury. It featured a trippy drawing of an Indian sadhu with a third eye, and the typeface used stylized art nouveau lettering that required a great deal of concentration to read.

Saturday, January 14, 1967, 1–5 p.m.

A Gathering of the Tribes for a Human Be-In

Allen Ginsberg, Timothy Leary, Richard Alpert, Michael Mclure

[sic], Jerry Ruben [sic], Dick Gregory, Gary

Snyder, Jack Weinberg, Lenore Kandel

ALL SF ROCK GROUPS

At the Polo Field, Golden Gate Park

FREE

Bring food to share, bring flowers, beads, costumes,

feathers, bells, cymbals, flags

* * *

It was just past dawn on the morning of the Be-In and Allen Ginsberg wasn’t really worried about the rumors, but he wanted to sanctify the gathering anyway. The day before, word had spread through San Francisco that a satanic cult had put some sort of a curse on Polo Field where the Be-In was scheduled to take place. A couple of hippies who lived near the park had found some chopped-up pieces of meat and bones in the field. In a community with a lot of mystics, many of them high on psychedelics, it hadn’t taken long for the paranoid theory to reach the ears of some of the “elders” who had been planning the event. Suzuki Roshi, founder of the San Francisco Zen Center, had given a blessing, but many in Haight-Ashbury were still a bit unnerved. Ginsberg, who had spent a lot of time in India the previous year, knew just what to do.

It had been an unusually rainy winter in the Bay Area but the sun was shining with barely a cloud in the sky and the temperature was around fifty degrees. Shortly after sunrise, Ginsberg, along with fellow poet Gary Snyder and a few of their close friends, performed a Hindu ritual called “Pradakshina,” which consisted of a slow, solemn walk around the field (which was 480 feet wide by 900 feet long) while reciting sacred prayers. This, the poets explained, was crucial for ensuring that the Be-In would be a mela—a pilgrimage gathering—and not just a big stoned party.

A dozen years earlier at the Six Gallery, which was just five miles away on Fillmore Street, Ginsberg had read his groundbreaking epic poem “Howl” for the first time. (The famous first line of the poem is, “I saw the best minds of my generation destroyed by madness,” but the poet’s own mind, no matter how far out he got, was as sharp as a razor.) Along with his friend Jack Kerouac’s novel On the Road, Ginsberg’s poem expressed a radically different vision of sexual morality, art, and the very meaning of life than that which characterized the prevailing ethos at the peak of the Eisenhower era, which was still under the dark shadow of McCarthyism. In the succeeding decades, Ginsberg and Kerouac became beacons of light for thousands of marginalized smart kids. One of those was Jerry Garcia of the Grateful Dead, who said in the late sixties, “I can’t separate who I am now from what I got from Kerouac … I don’t know if I would ever have had the courage or the vision to do something outside with my life—or even suspected the possibilities existed—if it weren’t for Kerouac opening those doors.” Ironically, Kerouac hated the hippies; he just couldn’t connect with the next generation. But Ginsberg had dived fully into the heart of the hippie movement.

The posters that had been put up around the Bay Area said that the Be-In would start at one in the afternoon, so Ginsberg was pleasantly surprised when dozens of people were already arriving by nine in the morning, just as the Pradakshina was ending. They kept coming and coming and coming. Previously, the biggest hippie gathering had been six thousand at the Trips Festival a year earlier. Before the afternoon was done, at least thirty thousand had shown up “to be.” Where the fuck had they all come from?

Although there were various theories about the best way to take LSD, there was no question that the drug created a powerful inner experience only some aspects of which lent themselves to verbal explanations. Experiences in which small groups of friends discussed the various theories of the meaning of life were not necessarily the same “trips” as those of people doing the same things in different homes, in different neighborhoods. So the idea of a “tribe” did not merely refer to high-profile clusters of hip celebrities like the bands or the Diggers or Ken Kesey’s Merry Pranksters or the Free Speech Movement veterans of Berkeley. It applied to hundreds of small groups with varying notions of community and inner experiences.

One of the reasons the external manifestation of tens of thousands of freaks felt so extraordinary was because of the notion so vividly held at the Be-In that an integrated matrix of hundreds of tribes could function as the nucleus of a new society. Looking back, it is not at all surprising that this turned out not to be the case. What was remarkable was that it ever felt that way on such a mass scale, even for a moment.

Many at the Be-In brought cameras, and within weeks, photos would be seen in magazines and newspapers around the world of the massive crowd, which included barefoot young women in madras saris, folk singers, self-proclaimed shamans, and motorcyclists. Some of the men dressed in Victorian clothes, Edwardian jackets, and velvet cloaks, with stovepipe or porkpie hats. Others looked more like cowboys, or Native Americans, and a few, like Ginsberg, like well-fed sadhus. There were lots of feathers, drums, esoteric flags, soap bubbles, and balloons.

Hundreds of the men had really long hair, way past their shoulders, longer than that of the Beatles. Many of the women wore long dresses, while others wore miniskirts and see-through tops; there were also quite a few mothers with small children. Some had masks and body paint; there were astrologers, jugglers, and a couple with shining eyes passing out tarot cards. But these were the veterans of earlier hippie gatherings. The bulk of this expanded community was still in jeans and khakis and wouldn’t have looked out of place at a folk festival.

Although Haight-Ashbury was a relatively integrated neighborhood, the hip community in the Bay Area at that moment was mostly white. Dick Gregory was the only scheduled African American speaker and he bailed at the last minute to attend a protest at Puget Sound. Jazz virtuosos Dizzy Gillespie and Charles Lloyd, who sat in on a couple of Airplane and Grateful Dead songs, were the only black musicians to perform.

A group of Krishna devotees with their distinctive shaved heads and single braids danced. On the periphery, a sole Christian evangelist with a bullhorn vainly tried to argue that hell and damnation awaited those who followed the lead of the speakers. The hippies smiled sweetly at him as they sauntered by.

Adding to the surreal feeling in the huge crowd was the fact that its transcendental craziness was happening adjacent to apparent normality. Golden Gate Park is one of the largest parks in an American city and a rugby game was being played on the other end of the vast field. A few local cops on horseback surveyed the crowd, but didn’t make any busts. For the moment, it was live and let live.