9,59 €

Mehr erfahren.

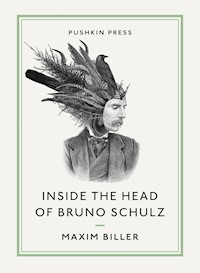

- Herausgeber: Pushkin Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

Do you see what kind of a madhouse this town of Drohobycz is now, Dr Mann? People here never think and act as they should!Locked away in a dimly lit cellar in a provincial Polish town, the writer Bruno Schulz is composing a letter to Thomas Mann, warning him of a sinister impostor who has deceived the gullible inhabitants of Drohobycz. In return, he's hoping that the great writer might help him to escape - from his apocalyptic visions, his bird-brained students, the imminent Nazi invasion, and a sadistic sports mistress called Helena.In Inside the Head of Bruno Schulz, Biller blends biographical fact with surreal fiction to recreate the world as seen through the eyes of one of the most original writers of the twentieth century. The novella is published alongside two short stories by Schulz himself, 'Birds' and 'Cinnamon Shops'.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Ähnliche

MAXIM BILLER

INSIDE THE HEAD OF BRUNO SCHULZ

Translated from the German by Anthea Bell

With two stories by Bruno Schulz

CONTENTS

INSIDE THE HEAD OF BRUNO SCHULZ

Praise be to him who creates strange beings.

S. Y. AGNON,And the Crooked Shall Be Made Straight

“MY HIGHLY ESTEEMED, greatly respected, dear Herr Thomas Mann,” wrote a small, thin, serious man slowly and carefully in his notebook, on a surprisingly warm autumn day in November 1938—and immediately crossed the sentence out again. He rose from the low, softly squealing swivel chair, where he had been sitting since early that afternoon at the desk, also too low, from his father’s old office, he swung his arms upward and sideways a couple of times as if doing morning exercises, and looked for two or three minutes at the narrow, dirty, skylight panes of the top of the window, through which shoes and legs kept appearing, along with the umbrella tips and skirt hems of passers-by up above in Florianska Street. Then he sat down once more and began again.

“My dear sir,” he wrote. “I know that you receive many letters every day, and probably spend more time answering them than writing your wonderful, world-famous novels. I can imagine what that means! I myself have to spend thirty-six hours a week teaching drawing to my beloved but totally untalented boys, and when, at the end of the day, I leave the Jagiełło High School where I am employed, tired and—”. Here he broke off, stood up again, and as he did so knocked the desk with his left knee. However, instead of rubbing the injured knee, or hopping about the small basement room, cursing quietly, he held his head firmly with both hands—it was a very large, almost triangular, handsome head, reminiscent from a distance of those paper kites that his school students had been flying in the Koszmarsko stone quarry since the first windy days of September—and soon afterwards he let go of his head again with a single vigorous movement, as if that could help him to get his thoughts out. It worked, as it almost always did, and then he sat down at the desk again, took a fresh sheet of paper and wrote, quickly and without previous thought: “My dear Dr Thomas Mann! Although we are not personally acquainted, I must tell you that three weeks ago a German came to our town, claiming to be you. As I, like all of us in Drohobycz, know you only from newspaper photographs, I cannot say with complete certainty that he is not you, but the stories he tells alone—not to mention his shabby clothing and his strong body odor—arouse my suspicions.”

Right, very good, that will do for the opening, thought the small, serious man in the basement of the Florianska Street building, satisfied, and he put his pencil—it was a Koh-i-Noor HB, and you could also draw with it if necessary—into the inside pocket of the thick Belgian jacket that he wore all year round. Then he closed the black notebook with the blank label at its first page, and stroked his face as if it did not belong to him. For the first time that day—no, for the first time in many months, maybe even years—he no longer felt that large black lizards and squinting snakes, as green as kerosene and with evil grins, were about to slither out of the walls around him; he did not hear the beating and rushing of gigantic Archaeopteryx wings behind him, as he usually did every few minutes; he was not afraid that soon, very soon indeed, something unimaginably dreadful was going to happen. When he realized that, he was immediately panic-stricken, for it must be a trap set for him by Fate.