10,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: John Wiley & Sons

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

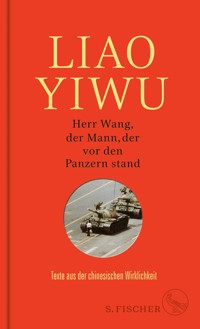

As a writer, poet, musician and dissident, Liao Yiwu is one of the most important chroniclers and analysts of contemporary China. In his books, he draws on his own experiences of imprisonment and mistreatment at the hands of the Chinese state to criticise abuses of power and give a voice to the downtrodden and disenfranchised.

In this powerful memoir, Liao Yiwu reflects on his own journey from imprisonment in Sichuan to his current life in Berlin, where he now works as a full-time writer. As China’s presence and influence on the international stage grows, this small book is a poignant reminder of the human cost of authoritarianism and of the power of the written word to bear witness to evil.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 70

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Ähnliche

CONTENTS

Cover

Table of Contents

Title Page

Copyright

The text

Notes

Appendix

End User License Agreement

Guide

Cover

Table of Contents

Title Page

Copyright

Begin Reading

Appendix

End User License Agreement

Pages

iii

iv

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

73

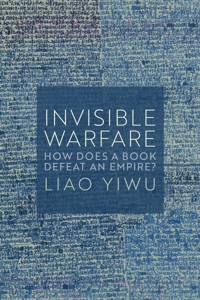

Invisible Warfare

How Does a Book Defeat an Empire?The Stuttgart Future Speech

Liao Yiwu

Translated by Michael Martin Day

polity

Originally published in German as Unsichtbare Kriegsführung. Copyright © 2023 Klett-Cotta – J. G. Cotta’sche Buchhandlung Nachfolger GmbH, gegr. 1659, Stuttgart

This English edition © Polity Press, 2024

Polity Press65 Bridge StreetCambridge CB2 1UR, UK

Polity Press111 River StreetHoboken, NJ 07030, USA

All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purpose of criticism and review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher.

ISBN-13: 978-1-5095-6295-4

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2023947422

The publisher has used its best endeavours to ensure that the URLs for external websites referred to in this book are correct and active at the time of going to press. However, the publisher has no responsibility for the websites and can make no guarantee that a site will remain live or that the content is or will remain appropriate.

Every effort has been made to trace all copyright holders, but if any have been overlooked the publisher will be pleased to include any necessary credits in any subsequent reprint or edition.

For further information on Polity, visit our website:politybooks.com

If one person engages in a game of chance with an empire, then the forces seem very unevenly stacked, but I won’t necessarily lose. As national memory is something abstract and easy to change in accordance with the needs of the regime, the original material evidence that constitutes history can be constantly altered, replaced, and destroyed … but the memory of personal disgrace will seep into the blood, instinctively affecting an individual’s speech and behavior – and this stigma can never be erased.

Most of my manuscripts are locked up in the filing cabinets of the Ministry of Security, and the agents there study and ponder them repeatedly, more carefully than the creator himself. The guys working this racket have superb memories; a certain chief of the Chengdu Public Security Bureau can still recite the poems I published in an underground magazine in the 1980s. While the literati write nostalgically, hoping to go down in literary history, the real history may be locked in the vaults of the security department.

The above two paragraphs are excerpted from pages 127 and 128 of the traditional Chinese-character version of June 4: My Testimony, published by Taiwan Yunchen Culture Company in 2011.1 Why do I write like this? I’ve forgotten. Like an old movie of past times and places, each shot is blurred due to damaged film stock. I rack my brains as I replay it, but to no avail – yes, I wrote the draft of that book three times, and the paper later was much better than the paper I used for writing in prison, which was so soft and brittle I had to write very lightly. Paper outside prison has adequate solidity and flexibility, so you don’t have to worry about puncturing it with the tip of a pen. Thus, I restrained myself and filled in a page of paper, and then how many thousand? Ten thousand? More? How many ant-sized words can be packed onto a page? Who knows.

I spent four years in prison for two poems, “Massacre”2 and “Requiem,” both of which railed against and condemned the Tiananmen massacre that began in the early hours of June 4, 1989. Fueled by extreme anger, I recited “Massacre” with the assistance of the Canadian Sinologist Michael Martin Day, who was living in my home at the time, and made it into an audiotape, which was distributed to over twenty cities across the country; then, after mustering a mob of sorts, we made “Requiem” into a performance art film. On March 16, 1990, I was arrested and imprisoned. About two dozen underground poets and writers were detained and interrogated, but only eight would be named as defendants in the first indictment in the case against this “counter-revolutionary clique.”

I passed through an interrogation center, a detention center, No. 2 Prison, and No. 3 Prison in Sichuan Province. During the two years and two months in the detention center, I wrote and preserved twenty-eight short poems and eight letters, which I hid in the spine of a hardcover edition of the medieval novel Romance of the Three Kingdoms. I used paste to “repair” and restore it before it was eventually taken out of the prison after passing through many hands. In the last prison, No. 3 Prison in northeast Sichuan, I secretly wrote more than two hundred pages of manuscripts. Over the years, the names and contents of these novel manuscripts have been changed and expanded many times. Now their names are fixed as The Transmigration of Ants, Love in the Time of Mao, and Underground Poets in the Time of Deng. They’re all linked to For a Song and a Hundred Songs, written after I was released from prison, to form a four-volume book with a collective title of Go on Living. The process of smuggling the first three volumes of Go on Living out of the prison was extremely complicated. During the sixteen years from January 31, 1994 until September 14, 2010, when I was out of prison and was approved to go abroad for the first time, these prison manuscripts were all hidden in a certain place, thickly camouflaged in all sorts of stuff (such as used diapers). I never thought of doing anything with them, and mentioned them to no one, so I was never really in any danger.

The epilogue of Underground Poets in the Time of Deng describes the sudden death of Hu Yaobang, the most enlightened general secretary in the history of the CCP (Chinese Communist Party), in the spring of 1989, which triggered a movement for political reform and spurred millions to take to the streets in demonstrations in dozens of major cities across the country. One of my contemporaries, an avant-garde poet with the pen name Haizi, committed suicide by lying on the rails at Guojiaying Railway Station in Shanhaiguan, a coastal town marking the start of the Great Wall, not too far from Beijing. After that, I was out of prison writing A Song and a Hundred Songs.

In the winter of 1992, I was transferred to No. 3 Prison, where many political prisoners related to the June 4 Tiananmen massacre were detained. I slept on a top bunk in a group cell. In the beginning, I wrote some irrelevant random thoughts that I let everyone pass around, but I had secret ulterior motives.

Originally, it was impossible for me to keep these secret manuscripts myself as the cells were subject to random searches. But I knew a paramedic downstairs who had been locked up there since the start of “liberation” in the 1950s. He had been a reporter from the Kuomintang’s Saodangbao (“Mop-Up Daily”). As he had been detained for so long, the prison guards ignored him. He was well read, and everyone called him Old Man Yang. Every time I finished writing a fragment, I handed over the manuscript to him to hide.