22,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The Crowood Press

- Kategorie: Fachliteratur

- Sprache: Englisch

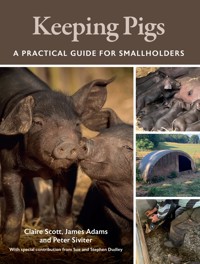

Written by experts in the field, Keeping Pigs – A Practical Guide for Smallholders is the only pig-keeping book aimed both at the small-scale producer and at keepers of pigs as pets that is written from a veterinary and keeper perspective. It offers practical and achievable advice about all aspects of pig husbandry and health, enabling readers to understand how their pigs cannot just survive, but also thrive. This detailed guide is an invaluable source of reference for anyone considering keeping pigs, as well as those who have already embarked on their porcine adventure. With hundreds of photos and diagrams, this book provides everything you need to know.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 425

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Ähnliche

First published in 2023 by

The Crowood Press Ltd

Ramsbury, Marlborough

Wiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2023

© James Adams, Claire Scott and Peter Siviter 2023

All rights reserved. This e-book is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 7198 4258 0

Cover design by Blue Sunflower Creative

CONTENTS

Introduction

1 Pig Choices

2 Legislation and Regulation around UK Pig Keeping

3 Biosecurity

4 Pig Housing and Environment

5 Feeding

6 Handling

7 Transporting Pigs

8 Making the Most of Your Vet

9 Diseases of Pigs

10 Medicines

11 Vaccinations

12 Parasite Control

13 Breeding

14 Pig to Pork

15 Common Procedures

16 Pig Death and Euthanasia

Conclusion

Glossary

References and Resources

About the Authors

Index

INTRODUCTION

The British pig can be characterised as a determined protagonist in a constantly evolving story. After World War II, a spate of notifiable disease and animal farming crises arose. ‘Mad cow disease’, ‘Foot and Mouth’ and salmonellosis led to distrust in the commercial meat-producing market. Alongside this, concerns of animal welfare on farms came to the fore. This has resulted in three movements that are of intense relevance to this book. They are as follows:

Sue and Stephen’s pigs are raised for meat, but are kept with intense love and dedication.

Pigs deserve better: Rearing and growing your own food is, to many, the best way to ensure confidence in its production. Barbara and Tom have inspired the masses to create their very own ‘Good Life’. Pigs, and buyers of their produce, should expect dignity and individual care throughout life and in death. In addition, such holdings are crucial for the preservation of rare breeds. This might sound a noble and romantic endeavour, but don’t forget that it can only be achieved with much hard work.

Tightening of red tape: In response to mistrust in commercially reared meat, the agricultural sector has strived to reassure consumers with changing legislation, introduction of farm assurance schemes, and strict supermarket contracts.

Pigs as equals: A growing group has moved towards a goal of equality amongst all living creatures, resulting in pigs occupying spaces in animal sanctuaries, gardens, stables, garages, conservatories and living rooms. They can be companions, best friends, surrogate children, or simply pasture ornaments.

So why is it important that our readers acknowledge these three dimensions? Firstly because it got us here, in the context of this book, a book that hopes to be read by, and to cater for, both the pet pig owner and the small-scale pig producer. This is no mean feat we are sure you will agree, but we hope that readers will identify with our common goal: to encourage the keeping of the happiest and healthiest pigs possible, no matter what their intended function or lifespan might be.

These pet pigs have no ‘job’ other than to provide amusement and joy to those around them.

Secondly, because it is important for you to know what you are up against, given that most smallholders aim to provide a better life for a pig than the life they would receive on a commercial pig farm. Therefore we will make reference to commercial farming, because we have learnt so much about pigs by farming them for so many years.

Throughout, we have strived to provide the most current and relevant information for smallholders keeping pigs in the UK. Due to the quickly moving and progressive nature of the pig sector, much of this has changed even during the two-and-a-half year writing process for this book. Therefore, readers must ensure that they are using the most up-to-date practices and following current legislation for their area. This will generally be achieved by consulting the extensive sources that we provide as reference material. Whilst we will try to update the book where possible, we can’t be held liable for this changing climate.

In the following chapters we will focus on preventing pigs from suffering from disease, which we regard as the best way to ensure happy and healthy lives. This encompasses ensuring that pigs have suitable nutrition and appropriate housing, as well as using vaccines and medicines appropriately.

By preventing health problems, first and foremost we protect our pigs from unnecessary pain and suffering. Secondly, preventing disease saves money, for example by avoiding the costs of emergency veterinary visits and unnecessary medicines, or by allowing pigs to achieve their growth and reproductive potential. Finally, treating disease is often attempted using an antibiotic. Preventing disease is therefore an excellent way to reduce the risk of the development of antibiotic resistance, which is a global health concern.

In this way we aim to equip you with some of the knowledge and practices that you will need to keep pigs. Mistakes will be made along the way, but learning from these will ensure a higher standard of welfare on your holding, and we urge you to keep striving for the best that you can possibly achieve.

These piglets are provided with everything they could need.

CHAPTER 1

PIG CHOICES

SHOULD I KEEP PIGS?

Before sourcing pigs, you must consider whether you can provide an appropriate home for them, by evaluating whether you can meet their needs. Keepers of pigs are required by law to have a copy of, and be familiar with, the ‘Code of Practice for the Welfare of Pigs’.1 Much of this book has been informed by the Code of Practice (which is how we will refer to it from now), but we aim to translate it into what is pertinent for smallholders and provide the tools to meet it.

By law, all keepers must have a copy of, and be familiar with, Defra’s Code of Practice for the welfare of pigs.1

The Code of Practice is built round a framework called ‘the Five Freedoms’, devised by the Farm Animal Welfare Council – FAWC – in 2007,2 which describes the needs of farmed animals. All pigs, even pets, are covered by farm animal legislation in the UK and are therefore protected by this framework. They are:

1. Freedom from hunger and thirst by ready access to fresh water and a diet to maintain full health and vigour.

2. Freedom from discomfort by providing an appropriate environment including shelter and a comfortable resting area.

3. Freedom from pain, injury or disease by prevention or rapid diagnosis and treatment.

4. Freedom to express normal behaviour by providing sufficient space, proper facilities and company of the animals’ own kind.

5. Freedom from fear and distress by ensuring conditions and treatment to avoid mental suffering.

Seemingly simple on the surface, these can be difficult to achieve simultaneously. To give an example: on indoor commercial pig farms, farrowing sows are often housed in ‘crates’ with their piglets for up to four weeks after the piglets have been born. This allows sow and piglets to be closely monitored, and the keeper can safely intervene when required. The ‘crate’ is designed so that piglets are not squashed and killed when the sow lies down. Rooms are temperature controlled. A heat mat and lamp is provided in a creep area for the piglets to keep them warm, while the sow lies on metal to allow her heat to exude from her. She is fed precisely and her intake monitored closely, as are her piglets. Slatted floors allow faeces to drop away from the pigs, meaning that disease from these faeces is much less likely to pass into the mouth of another pig.

However, these pigs have little opportunity to display natural behaviours. Sows cannot turn round in their crates, and they cannot interact with each other. Slats mean that sows can only be given limited nesting material, as too much straw would block up the slats. Therefore, despite so many measures intended to look after the sow and piglets, her freedoms are compromised for that period.

This more commercial outdoor pig farm looks great when the sun is shining, but can be much more difficult to manage in adverse weather.

Conversely, a farrowing sow kept on an outdoor commercial pig farm (about 40 per cent of UK pig production3) will generally be housed in a tin or plastic pig arc, which in the summer can be sweltering and in the winter will be fairly chilly – however, body heat does a good job at keeping her warm. Monitoring is limited to ensuring that every sow has come out to eat each morning, at which point piglets are briefly checked. In the summer the ground is dusty and rock hard, while in winter sows may be up to their nipples in mud just to leave their arc to eat, drink and defecate. Despite these challenges, these sows and their piglets live with the freedom to act like pigs: to root in the dirt, to wallow, and to frolic in the sun.

In this way, it is important to note that where improvements are achieved in one of the Five Freedoms, there may be a cost to another. It is up to keepers to balance these factors within legal and best practice frameworks.

Unfortunately good stockmanship isn’t always this idyllic!

Is one system better than the other? That is likely to be highly personal. We believe that, once the basics have been achieved, it is good stock(hu)manship that is key to well-kept pigs, rather than the system in which they are kept. To achieve this, pig keepers should embody FAWC’s essentials of stockmanship 365 days of the year (pigs do not care that it is a Sunday morning). These are:2

Knowledge of animal husbandry: Sound knowledge of the biology and husbandry of farm animals, including how their needs may be best provided for in all circumstances.

Skills in animal husbandry: Demonstrable skills in observation, handling, care and treatment of animals, and problem detection and resolution.

Personal qualities: Affinity and empathy with animals, dedication and patience.

Only if you feel that you are able to meet these qualities and fulfil pig needs in a considered and caring way, should you proceed with the idea of keeping pigs.

Before sourcing pigs, it is really important that readers at least understand the basics of pig care to ensure that a suitable home is achieved.

THE SMALL-SCALE PRODUCER

We recommend starting out with two or three recently weaned pigs to rear and send for slaughter. There is so much to learn concerning pig rearing before breeding should be embarked upon. When choosing your weaners, the following questions should be considered:

Rearing three weaners is preferable to two, in case something disastrous happens to one.

How many? Pigs are social creatures and should not be kept alone, so always buy more than one.

What sex? Initially, buy male pigs as you are much less likely to become attached to them and to keep them for breeding. The decision to send your first pigs to the abattoir can be tough - however, adolescent male boars will make that decision as easy as possible. To avoid pregnancies, buy pigs of the same sex. Pigs breed very early and may take you by surprise - and pigs don’t have the same social boundaries as humans, so will breed with their siblings without worry.

When? Start by rearing pigs over the summer, but try a winter batch before breeding any pigs to see how your system copes with the challenges that adverse weather and short days bring.

BOAR TAINT

Well-meaning pig keepers may warn against male pigs due to ‘boar taint’. Boar taint is the smell or taste of male pig meat that can occur from the production of male sex hormones. It is very unusual in rare breed pigs, probably due to their slow maturation rate. Rare breeders we meet have never noticed it, even those who have killed boars that have actually ‘worked’ (served sows). Therefore it is not a good reason to request female weaners or to castrate male weaners.

Even a working male such as this boar at Millhouse Nursery is unlikely to exhibit boar taint.

Where From?

Rearing weaner pigs for meat is critical to the survival of rare breeds. Only the best pigs from each litter should be used for breeding, and therefore the others are destined for a dinner table. The phrase ‘the only way to keep rare pig breeds is to eat them’ really is true. Beyond that, we believe that choice of breeder is more important than choice of breed. You will have time to try different breeds before you think about breeding any pigs yourself, and therefore we would most like you to find the perfect breeder, in preference to the perfect breed.

When deciding on a breeder look for someone who:

• birth notifies their piglets: without this, pigs may well not be pedigree and you are not acting to preserve a breed.

• is local to you: not only will logistics such as your initial movement be easier, but you can benefit from their network and utilise relationships that they have built up, such as a vet or an abattoir.

• provides mentorship and support: good breeders want to know that their pigs are going to an excellent home.

Several breeders also run pig courses where you can get to know their pigs, learn about pig management, and ask lots of questions. Sue and Stephen’s course promises that you will be Large Black enthusiasts by the end of the day!

Alternatively, contact a few breeders and arrange to see their holding. To make sure that you aren’t spreading diseases, leave at least three days between visits, and wear clean clothes, and thoroughly clean wellies. If you are not happy that their pigs’ needs are met, walk away. You don’t want your first pig-keeping experience to end in tears. If you want to rescue a pig, there are many farm animal sanctuaries happy to assist you.

QUESTIONS TO ASK THE BREEDER

The following questions are useful to discuss with breeders:

Timing

• When are they expecting litters? They should have a good idea if running a tight ship.

• At what age do they wean?

• At what age do they sell weaners?

• At what age do they sell pigs for market?

This will give you an idea of how long you will have to keep the pigs before they are finished.

Networks

• Do they have a good relationship with a vet that you could also use? Be wary of keepers who don’t advocate cultivating a good working relationship with a vet.

• What abattoir do they use?

• How do they get there?

• Do they have a trailer they could lend you for the day of marketing?

Husbandry

• What do they feed the pigs?

• How do they enclose their pigs?

• Will pigs arrive electric-fence trained?

• What is their health routine, especially in terms of vaccines, worming and husbandry procedures?

• Are there any diseases to be aware of?

KEEPING PIGS AS PETS

The decision to keep pigs as pets is very different from that of a producer, not because they are different animals, but because we place different requirements on them and often place them in environments that are not designed for a pig. Therefore very specific attention must be paid to meeting their specific species needs so that unintended issues do not arise over the many, many years that they are likely to live for.

Pigs have a need to express natural behaviour, such as rooting and investigating their space as well as roughly playing with pen mates. Treating pigs inappropriately, or not giving them a suitable outlet for these behaviours, is likely to lead to behavioural ‘problems’ such as aggression or destruction. Punishing pigs that express these behaviours will only make these worse.

It is also likely that others will not see your pig as they would a dog. A pig’s noisy and destructive natural behaviours may lead to issues around neighbours’ complaints, lack of holiday care, unsympathetic landlords, and life changes meaning that a pig is no longer suitable for you.

Even pet pigs are best kept with other pigs in grassy paddocks where they can express natural behaviours.

For these reasons, rescue organisations are currently filled with pigs purchased as pets that were no longer suitable for their first home. Many will be ‘micropigs’ that outgrew their name. Many will be accidental families from brother-sister matings. Others will be in dire straits after being given completely inappropriate care in their first home. Therefore it is imperative to do the appropriate research before bringing home pet pigs. A large part of this will be considering how you will allow your pet pigs to be pigs.

If you are considering pet pigs, please reach out to a rescue organisation or farm animal sanctuary near you. By purchasing from a rescue organisation you are likely to acquire an older pig that is more predictable behaviourally. For example, if you would like pigs that are less likely to destroy ground, a sanctuary can show you pigs that do not do this.

Adopting a fully grown pig will also be preferable, to avoid any ‘micropig’ mishaps where a pig grows to a much larger size than expected. A ‘minipig’ or ‘micropig’ is not a breed, but a mixture of small pig breeds where the smallest pigs from each litter were bred together over generations (often also resulting in genetic problems from inbreeding). This means that ‘large pig’ genes can still be in the mix and can crop up sporadically. Furthermore, unscrupulous breeders will lie about the age of pigs or hugely restrict feeding of their own pigs so that their growth is stunted. In different hands these pigs can grow to be much bigger!

There are some fantastic farm animal sanctuaries where those who run them will mentor and guide you to ensure that you will make an appropriate home for their pigs – but be sure always to do your own research, and check advice with your vet.

Wherever you do source pet pigs, it is absolutely imperative that pigs are not housed alone. They are highly social creatures that need other pig company. Housing pigs alone will eventually cause behavioural and aggression problems. Pet male pigs must be castrated to avoid unwanted pregnancies and to reduce boarish behaviour, such as aggression or mounting, later in life.

ANIMAL SANCTUARY CHECKS

Before giving you a pig, a farm animal sanctuary should do the following:

• Check your premises, and not rehome to a holding where pigs will be kept exclusively indoors.

• Demand details such as a CPH number and other legislative adherence.

• Not rehome lone pigs unless there is a very specific reason in a particular pig.

• Be able to discuss pig-specific husbandry needs at length.

BREED CHOICES

As discussed, we believe that your breeder choice and future mentor is far more important than the choice of breed. However, we also think that preserving rare breeds is an admirable part of small-scale pig keeping, and therefore we would like to devote some time to discussing some of the breeds available to you. So whilst keeping weaners, before you consider branching into the world of breeding, keep a few different breeds from different breeders (not at the same time – you shouldn’t mix weaners from different sources for health reasons) and see which you prefer and what suits your system.

Informing Your Choice of Breed

Size and Character

Big pigs are powerful, and some breeds are boisterous. Your own situation will inform what is appropriate in this respect, and whether you want a smaller breed such as a Middle White or Berkshire, or a large pig such as a Gloucester Old Spot or Large White. Obviously, any pig breed can be kept as a pet given appropriate conditions, but a very large pig is far less practical. The Kunekune, for example, is a classic pet pig breed.

Rooting and investigating the ground around them is a natural behaviour for pigs.

Rooting

Do you want pigs to clear a patch of land, or would you like the least destruction possible? Bear in mind that any pig can root, but in general, the shorter its snout, the less power and destruction it will bring, looking to the Kunekune and Middle White as examples.

Rarity

The vast majority of commercial pig producers breed mixed-breed pigs and rarely have pure bloodlines on farm. Therefore our only credible chance of maintaining these pure breeds is through our network of small-scale pig producers. Details of these rare breeds are found from the Rare Breeds Survival Trust (RBST).4 Do remember that rare things are often rare for a reason, and you may need to accept some poor litter numbers or conception rates from the rarest options.

If this is your intent, please only buy stock from breeders who register their pedigrees. If they are not registered, they are worthless to this intent. There are different rules for different classes of BPA members, but in essence the following rules apply:

• Pigs that could be used for breeding should be bought from a pedigree breeder. Each pig should be birth notified and identified by an individual ear number.

• Weaners bought for fattening should be birth notified but need not be individually identified. This is to ensure that the parents are pedigree and that the breed is therefore being preserved. Buying cross-breeds as fattening weaners will still act to preserve rare breeds as long as both parents are pedigree. However, these pigs cannot be herdbook-registered breeding stock and must not be bred from in order to maintain the breed.

• When weaners are bought, they must be transferred to you on the BPA Grassroots database, which will enable you to sell the meat with ‘Pedigree Pork’ certificates. To sell pork as ‘Pedigree Pork’ you also need to have joined the BPA’s Pedigree Pork Scheme.

Meat Characteristics

We have yet to meet a breeder who doesn’t think that their pig meat is the best, but some will profess to extra qualities such as fat marbling.

SOME RARE UK PIG BREEDS

Once you have narrowed your choice into some kind of specification, you may find it helpful to build up a certain knowledge on each breed. The details of many breeds are found through the British Pig Association (BPA), although British Kunekunes and British Lops have their own separate societies. We have also provided a brief snapshot of each breed from some of our most esteemed keepers and champions of each breed. We thank them for their amazing contributions.

The Berkshire

Thought to have originated around the Thames Valley in the 1790s, the Berkshire was a large, tawny red pig, spotted with black, with a long body, ears that were lopped, short in the leg, and larger and coarser than today’s Berkshire. Asian blood was introduced in the 1800s, making the body shorter and deeper, and the ears much smaller and more in line with what we see today. Modern Berkshires must have six white points, namely the face, all four feet and the tail. They have fine, dished faces of medium length and fairly large pricked ears; the head should not be coarse.

A Berkshire sow

They are kind, docile pigs that produce good litters and milk well, and are easy to manage. One of the smaller of the traditional breeds, they are quick to finish to pork weight, killing out at between 60 and 70kg. They are good food converters, and do well whether living in or out. Like any pig they will root, and so enough space to rotate their rooting ground is needed. The delicious meat is very sought after by butchers and restaurants. Popular with the Japanese, Berkshires command a good price as Kurobuta pork. Pigs producing this pork must have a pedigree from an established herd in either England or Japan. The fat is marbled throughout each cut, allowing the meat to cook evenly and giving a much juicier result; it also has a sweeter taste.

Sharon Barnfield, Kilcot Pedigree Pigs

The British Landrace

The British Landrace is a white breed with short, lopped ears. The breed first came to the UK from Sweden in 1949. Other imports followed from 1953 onwards, and the British Landrace Society was created. New bloodlines were then imported in the 1980s from Norway. The breed expanded rapidly, and is one of the UK’s most popular breeds, however it has suffered with low numbers of pedigree registrations. With only twenty-six registered pedigree breeders, sow numbers have now dropped to 121, with only 152 registered from the last breed survey in 2021; they are now on the RBST priority list.

A fine British Landrace sow.

The breed performs well in both indoor and outdoor management systems. Sows are able to rear large litters, and make fantastic mothers. The Landrace has a good temperament, but sows can be very protective of their piglets, so are best suited to more experienced pig keepers.

One of the greatest strengths of the British Landrace is its undisputed ability to improve other breeds when used to produce hybrid gilts. Over 90 per cent of hybrid gilts in Western Europe and North America contain a Landrace bloodline to help with meat production. Piglets have a good daily weight gain and a high lean-meat content. They have a superbly fleshed carcass, and are ideal for bacon and pork production.

Grace Bretherton, Junior Pig Club Youth Ambassador

The British Lop

As its original name suggests, this pig is long and white, with lop ears reaching to the tip of its nose. The British Lop Pig Society was formed (as the Long White Lop-eared Pig Society) in 1920, and has remained independent ever since, making it the cheapest route to pedigree registration, with both membership and registration fees very low.

A prize-winning British Lop boar.

The breed is very docile and easy to manage; indeed, a single strand of electric fence wire some 30cm above the ground will confine these pigs. Several years ago the writer’s son showed a Lop sow at the age of three! The breed is noted for its large litters of fourteen to sixteen piglets, but it is clumsy, and two or three might be lost when the sow lies down.

Piglets should reach pork weight in about sixteen weeks, when there will be under 10mm of fat cover. Bacon weight is achieved in about twenty-six weeks, when there will be around 25mm of fat. Most importantly, the skin and hair are white so there is no discrimination by the butcher. Conformation is good, with the length and ham size that the butchers prefer. The meat is succulent with intramuscular fat, and in several taste tests has come out top.

Frank J. Miller, former Chairman and Secretary of the British Lop Pig Society

The British Saddleback

The Saddleback is a semi lop-eared pig with ears facing forwards; it is black, with a band of white hair running from one foot over the shoulders and back to the other foot. There can be white on the nose, the tip of the tail and the back feet. The white hind feet are a throwback to the Essex Saddleback, dating from the time before the Essex and Wessex Saddlebacks were amalgamated in 1967.

Champion Saddleback boar ‘Watchingwell Dominator 130’, otherwise known as ‘Dylan’.

The Saddleback sow must have twelve evenly spaced teats, and often has large litters – our first sow, ‘Stripe’, had nineteen in her first litter and raised them all! She gave us a great introduction to showing as it was so easy to do anything with her – and indeed, this is a very strong characteristic of the breed.

Saddlebacks are fantastic mothers, generally being very careful, and they happily tolerate having humans around the piglets. We farrow our Saddlebacks both indoors and out successfully, with and without heat lamps; the average litter is ten to twelve piglets, but is often more. They love grazing; ours have paddocks of about an acre for three, and they also have a wallow to play in.

The Saddleback produces wonderful meat, be it joints, hog roasts, sausages, hams or bacon; it is truly versatile. The weaners reach pork weight in approximately sixteen weeks.

In my opinion the Saddleback is the best pig for those new to the world of pigs.

Sharon Groves, committee member British Saddleback Breeders’ Club, BPA British Saddleback breed representative

The Duroc

A large-framed auburn pig, the Duroc couldn’t be better suited to the smallholder. Originally from America, Durocs were derived from the early ‘Red Hogs’. The breed was unsuccessfully introduced to the UK in the early 1970s, then a decade later was successfully re-imported. It is now popular worldwide in the commercial sector.

Duroc sow ‘Portbredy Lena 1337’.

Attentive and protective mothers, litter sizes range from ten to fourteen; however, for safety, minimal piglet handling is advised – but when they are not suckling, the sows are amongst the most docile. Their thick winter coat ensures they are able to cope with cold, wet winters.

Commonly used as a terminal sire, the Duroc can also be used this way on the smallholding. Thus crossing a Duroc boar with a traditional sow that is cheaper to maintain with less feed required will improve the meat quality of the offspring, with better marbling, flavour and growth rates.

The Duroc grows fast, with good muscle quality, and fat that is marbled throughout the muscle rather than in a layer under the skin. The Duroc can achieve a deadweight of 60kg by eighteen weeks of age, with a subcutaneous fat measurement of less than a quarter of an inch. Durocs need a high-protein, high-energy compound feed. Fruit and vegetables simply limit the feed intake and inhibit potential.

Dr Oliver Giles BVMSci, MRCVS, The Tedfold Herd of Pedigree Pigs

The Gloucester Old Spot

The Gloucester Old Spot is a large pink pig with black spots: these should cover less than 50 per cent of the body. They have a dished face, and lop ears that reach almost to the end of the nose. Spotted pigs were first recorded in 1913. Called Old Spots, they originated around the Berkeley Vale area and were kept in cider orchards and on dairy farms where they were fed on the waste from these enterprises. Folklore has it that the spots are from the apples falling and leaving bruises on the backs of the pigs.

A Gloucester Old Spot sow.

Gloucester Old Spots are good milky mothers, producing litters of eight or more, and are docile around farrowing, which makes them a good beginner’s pig. On top of this, they are attractive pigs, making them sought after by smallholders. All pigs will root and Gloucester Old Spots are no exception, but a good-sized enclosure or two will allow you to rotate them to let the ground recover.

They are a good dual-purpose pig, ideal for producing both pork and bacon, and they are easy to manage, happily living either in or out. They convert food well, and grow to either pork or bacon weight without an excessive amount of expensive concentrate food. The meat is much in demand, making them a good breed on the selling front.

Sharon Barnfield, Kilcot Pedigree Pigs

The Kunekune

Originating from New Zealand, Kunekunes were brought to the UK in the 1990s and quickly became popular. However, there are only seven female bloodlines and four male; one sow line has already been lost, and numbers of some of the other lines are diminishing, making the breed vulnerable.

A Kunekune sow.

There is much variation in colour and coat: they can be bald, smooth or hairy, and sometimes curly! Colours range from light cream through to black, including ginger, brown, ‘gold tip’ and with patches of colour.

Kunekunes are an ideal starter pig as they grow very slowly, making them manageable for longer. They are also docile and intelligent, and can manage on less ground than larger pigs because they are less destructive. They are good, milky mothers, farrowing with ease and producing litters of three to twelve piglets. Regarded by many as a pet pig, they are easy to train to basic commands. Their gentle nature and varied colouring make them ideal for visitor attractions, and although good mothers, they are not too protective, making it easy to interact with young piglets.

A slow grower inclined to fat, they are cheaper to rear for the table, but are not ready to slaughter until twelve to eighteen months of age at 50–70kg, providing small but delicious joints of dark meat. They also make perfect sausage pigs.

Wendy Scudamore, Former Chairman of The British Kunekune Pig Society

The Large Black

The Large Black is a large, black, lop-eared pig whose origins lie with the Old English Hog. The black hair makes them resistant to both sunburn and cold, and pre-war they were exported worldwide. Numbers plummeted post-war and became critical. The active and welcoming Large Black Pig Breeders’ Club was founded in 1996 and gives advice to anyone interested in the breed. Today, Large Blacks are rated ‘priority’ by the RBST, but there are more breeders than might be expected as herd sizes tend to be small.

‘Cerridwen’, a lovely Large Black sow from the particularly rare ‘Queen’ line.

As favourite characteristics, friendliness and flavour both rate highly. Large Blacks have such personalities – you will be constantly laughing at their antics. On the other hand, breeding animals can attain significant size – our boar Bran is around 400kg, so simply scratching can cause damage.

They are not great rooters, and unless confined to areas that are too small, are unlikely to escape, so stock fencing is generally adequate. Quick learners, they can easily be trained to electric fences, and they are friendly, intelligent and curious, enjoying interaction with humans. They are very easy to handle despite their large size. The breed produces litters of eight to ten, and they are excellent, milky mothers.

Slow growing, they can become fat if overfed. With care, they give a dark, succulent meat, marbled with delicious fat, making the breed excellent for charcuterie. Porkers slaughter well at seven months, producing a 65–75kg carcass. Although the hair is black, the skin, and therefore the crackling, is white.

Stephen and Sue Dudley, Black Orchard Large Blacks

The Large White

The Large White is a white pig with pricked ears, a dished face and a straight back. The breed’s origins are in Yorkshire, and in some countries it is known as the Yorkshire pig. Farmers started selecting white pigs with prick ears in the nineteenth century, and in 1884 the first herd book was published. From then onwards the breed increased rapidly in popularity, helped in no small part by the demand for the breed all over the world. In fact, the Large White pig can be found in just about every country in the world where there is a pig industry. In the UK the breed is the foundation of most breeding company programmes. However, pure breed numbers have dropped dramatically in the last twenty years to stand at just 289 sows and forty-five breeders, with some female lines being perilously close to extinction.

A young Large White boar from the ‘Viking’ line.

The Large White is a good mother and will produce litters of ten or more piglets for many years in both indoor and outdoor systems. Kept outdoors, a wallow is essential in the summer months to prevent sunburn. These pigs are easy to handle and have a good temperament.

The Large White is the ultimate meat-producing pig, being ideal for both pork and bacon production. Even if kept to heavier weights they do not lay down excessive amounts of fat, and produce a carcass that grades well at all weights. They grow well, producing an ideal carcass for the modern butcher, with just the right amount of fat covering on the loin. Fed correctly they will reach 90kg liveweight in 150 days.

Nick Kiddy, Solitaire Farm, BPA Large White breed representative

The Mangalitza

An extremely hairy breed, the Mangalitza has three colours, red, blonde and swallow-belly, and when these are bred together huge variations result. Created in the 1830s, each colour produces a different type of meat. Its fat was so prized that the Mangalitza was traded on the Vienna Stock Exchange, but by the 1980s the breed was near extinction. Thankfully it was saved, but it is still rare in the UK, with only eighty-seven sows and twenty-nine boars in 2019. Mangalitzas have black trotters, snouts, teats and tail tassels, and the ears can be pricked or floppy. The piglets are born with stripes, but these soon fade.

A blonde Mangalitza sow from Otterburn Mangalitza.

Whilst they are perfect for smallholders, being placid and friendly, they can be challenging escapologists. They don’t root, they plough and quarry, and will dig under fences. The sows can be protective, so the best thing is to leave them alone - they will introduce you to their piglets when they are ready. Litters average six, but can be as large as ten.

Slow growing, they are not ready to process until they are eighteen months old, when they yield around 120kg. They improve with age, and we have processed pigs as big as 350kg and as old as eight years. The meat is unique, deep red and much nearer beef in taste. It can be heavily marbled, and the back fat is high in monounsaturates, with the ratio of fat to meat as high as 60/40. They are a charcutier’s dream, and an amazing all-rounder for joints, sausages and bacon. The fat is perfect to add moisture to other meats, and can even be used in pastries and cakes, like butter.

Lisa Hodgson, Otterburn Mangalitza, BPA Mangalitza breed representative

The Middle White

The Middle White pig is an early-maturing pork pig, and is one of the most recognisable pigs, with its moderately short face, broad dished snout, and large pricked ears. The breed was first recognised in 1852 at a show in Yorkshire, where the judge decided that some pigs were too small for the Large White classes and too large for the Small White classes, so the ‘Middle’ White class was created. In the 1930s it was the most populous breed in the country, but it is now amongst the rarest British breeds. It is still farmed in Japan, where the quality of its pork is highly prized, and there has even been a shrine erected to honour the excellence of the breed. The pork is popular with chefs in the UK, and it is also used to supply the suckling pig trade.

A Middle White gilt.

It is a friendly pig that is easy to manage, and is therefore ideal for novices and smallholders. Sows make great mothers, milking well and raising litters averaging eight to ten in size. They are hardy, and can live outdoors all year round with no issues and don’t take up a huge amount of space, but like all other pigs, they will root, and so space to rotate them on to fresh pasture and allow restoration of used ground is of benefit.

Youngsters tend to be weaned at eight weeks of age and will achieve pork weight in six months, allowing for variables, on a standard sow and weaner ration. It is also possible to take them on for a bit longer to achieve bacon weight, with careful feeding to prevent excess fat.

Cathy Baker, Rockwood Rare Breeds

The Oxford Sandy and Black

Historically referred to as the ‘plum pudding pig’, the Oxford Sandy and Black is one of the UK’s oldest native breeds. After becoming almost extinct by the 1970s, today there are thirteen sow lines and four boar lines remaining, with approximately 420 breeding sows and 120 boars (2021/2022).

An Oxford Sandy and Black boar from the Broadways herd.

These pigs have a pale sandy to rust-coloured coat with patches of black. They have lopped or semi-lopped ears, a medium-length nose, white socks, a blaze and a tassel, and solid conformation with a good shoulder and hams, and a proud, strong, straight back.

They make excellent mothers, farrowing litters with an average of eight to twelve piglets. They are easy to manage, move and handle due to their docile temperament, so are an excellent choice for a smallholder or new pig keeper. They are slow growing, and medium to large in size, and are very hardy to weather conditions. They like to live outdoors with the freedom to root and roam. An Oxford Sandy and Black will typically finish between six and eight months at 65 to 85kg.

Tania Whittick, Broadways Rare Breed Porkers

The Tamworth

Tamworths originate from Tamworth in the West Midlands. The latest breed survey (2021) showed that there are only 239 registered Tamworth sows, only 300 total registered pigs, with only seventy-nine breeders. It is the only whole-coloured ginger pig, with pricked ears and a lively curiosity.

A fine Tamworth sow.

The Tamworth is a good smallholder’s pig. They make very good mothers, are very milky, and generally just get on with their task. Litters are usually a manageable size (our average is eight reared per litter), and they do it without needing expensive creep feed. With their long noses, they are good at rooting, and clear scrubland very well.

Tamworths are equally delicious for pork and bacon. Over the last twenty years or so they have improved considerably in both conformation and temperament, an achievement due to a small group of dedicated breeders. Pigs reach pork weight (50 to 70kg) between six to eight months, or bacon weight (80 to 100kg) between eight to twelve months.

Bill and Shirley Howes, founding members of the Tamworth Breeders’ Club

The Welsh

The Welsh Pig Society was formed in 1922, and the commercial benefits of the breed were promoted, which led to a steep increase in numbers. In 1950 Landrace lines were introduced, and the government identified the Welsh as one of the three significant breeds to be used in the British pig industry. Currently there are 523 Welsh pigs registered; however, sadly the breed is on the RBST ‘At Risk’ register.

A lovely Welsh sow from Hideaway Farm.

The Welsh pig is a rare breed native to Wales, hardy and an ideal smallholder’s pig. Welsh sows are wonderful, milky mothers, producing large litters. The Welsh pig is placid and easy to handle, white in colour, with lop ears, and pear-shaped with good loins and hams. They are happy indoors but do love to root outside in a well fenced paddock or wood. The Welsh has many positive characteristics: my favourite is their personality, though one downside is that they are prone to sunburn, so stock up on suncream to prevent crispy ears in the summer!

Because the Welsh produces excellent bacon, sausages and pork cuts the piglets are easy to sell to grow on. They reach porker weight at roughly twenty-one weeks, so feed conversion is efficient; the pork has just the right amount of fat, and the flavour is sweet and the meat succulent.

Corinna Taylor, Hideaway Farm Pedigree Pigs

ASSURANCE SCHEMES, INCLUDING ORGANIC PIG REARING

In this label-loving world, it can be tempting to do the same for our pigs. Therefore it is really important to understand what you can and can’t say about your produce, and the steps you need to take to ‘certify’ the holding or the meat.

Organic Pig Production

Organic production aims to use natural substances and processes to minimise the environmental impacts of food production, as well as meet high standards of animal welfare.

The term ‘organic’ is protected under EU law, meaning that to label a holding or a product as organic you must meet very specific regulations as stipulated by the EU’s Organic Regulations.5 This can only be achieved with the certification of an organic assurance scheme, which will check that you have met the requirements, the most popular of which in the UK is the Soil Association. It is really important to note that you cannot call yourself organic without going through the process of conversion (generally taking two to three years) and without meeting every part of the EU’s Organic Regulations. Stipulations will be detailed and far reaching, from the feed you provide, the way you rotate land, and the way that you use veterinary medicines. Pigs are required to be kept outdoors (unless in the final finishing stage), and are only weaned after forty days, which is much later than most other commercial holdings. If you are interested, have a look at the scheme standards for an organic certification body such as the Soil Association.6

Red Tractor Certified Standards7

The Red Tractor label signifies that a holding has reached a base level of standards so the produce is suitable to be sold by supermarkets in the UK. Standards broadly reflect the Code of Practice, with the extra stipulation that pigs must not be castrated under Red Tractor. The scheme allows a mechanism for checking that the food in our supermarkets is produced to an acceptable standard. For pig producers, that includes a three-monthly visit from their vet to check the pigs and review their health and welfare plan, as well as a yearly audit from a Red Tractor inspector. This three-monthly vet visit means that producers and vets develop very close relationships, and vets understand these units thoroughly from seeing them both routinely and when things go wrong.

Most smallholders selling produce locally or to farm shops and butchers will not be required to show Red Tractor certification. But for those wanting greater support and more checks to ensure that they are meeting the standard, Red Tractor offers a sensible set of guidelines to follow. It is important to note that pork imported to the UK (about 60 per cent of the pork that we eat3) does not have to meet the same standards, and often falls far short of them.

RSPCA Freedom Foods8

This assurance body gives an extra layer of certification and allows produce to be labelled with the ‘RSPCA Assured’ label. It can be thought of as an enhanced Red Tractor. It is written with the Five Freedoms2in mind and has extra stipulations around welfare, such as greater space requirements for all pigs. This is especially pertinent for sows during the suckling period; traditional farrowing crates that limit sow movement to reduce the likelihood of piglets being squashed are not allowed under the scheme. The scheme is a good one for smallholders as it ensures that producers are providing a product at least in line with our higher welfare supermarket producers, who will be required to have both Red Tractor and RSPCA Assured certification.

The Wholesome Food Association9

This scheme markets itself as a low-cost alternative to organic certification with a similar intent to raise natural produce using sustainable, non-polluting methods. They don’t have scheme standards but instead have a set of principles that producers pledge to adhere to. This scheme is built on trust and therefore producers are not inspected but have an ‘open gate’ policy allowing consumers to visit the holding, for example through a yearly open day. Producers are then able to label produce with the Wholesome Food Association symbol.

Sue and Stephen’s beautiful pork, labelled with care.

Other Labelling

Outdoor pigs can feature extra labelling if they meet certain requirements, as described in the Code of Practice for the Labelling of Pork and Pork Products.9 It is important that producers only call or label produce with these terms if they are sure that they meet these descriptions. This is so that consumers can be sure of what they are buying, allowing them to make informed choices about their food. More information can be found on the Pork Provenance website,9 where producers can sign up for this voluntary Code of Practice.

Free range: Pigs are born outside in fields where they remain until they are sent for slaughter. They are free to roam in very generous space allowances within defined boundaries, with good rotational practices. Breeding sows are kept outside in fields with generous minimum space allowances.

Outdoor bred: Pigs are born outside in fields where they are kept until weaning. Breeding sows are kept outside in fields with generous minimum space allowances. Pork and pork products labelled as ‘outdoor bred’ will also contain a statement about how the weaned pigs are subsequently farmed.

Outdoor reared: Pigs are born outside in fields, where they are reared for approximately half their life (defined as having attained at least 30kg). Breeding sows are kept outside in fields. All pigs are provided with generous minimum space allowances. Pork and pork products labelled as ‘outdoor reared’ will also contain a statement about the way the grower pigs are then subsequently farmed.

Assurance schemes tend to come with a cost that you may decide is not warranted for you, especially if you would sell produce regardless of this labelling. However, we do still encourage you to look at the assurance scheme that best aligns with your intent, and to refer to and act to meet that scheme’s standards. Yes, you won’t be able to use their labelling, but you can be more content that you are providing the life for your pigs that you envisaged, which for many is to go above and beyond that of the pig products you can buy in a supermarket.

When consulting scheme standards, be sure that you are consulting the most up-to-date document (which may no longer be the documents on the reference list at the back of this book) as standards change frequently.

SOCIETY MEMBERSHIPS

Networks are hugely important to smallholders; they allow pig keepers to see how it is all put into practice.

Societies for All

Smallholding Vet Schemes

If you aren’t already registered with a livestock vet, try to find one with enthusiasm for pigs, and preferably one that runs a smallholder scheme. A smallholder scheme normally means that a practice will have vets dedicated to it with a specific interest in meeting the needs of smallholders. These needs can be quite different from commercial clients, and it generally means that smallholders and vets will be on a similar page. Pete’s practice, Synergy Farm Health, has a thriving smallholder scheme that provides regular meetings, a newsletter and health planning as part of its membership.

Pete running a smallholder pig meeting in his younger days.

Social Media Groups

There are hundreds of social media groups that pig keepers can join. Generally, each breed will have one, as will other groups, such as minipig keepers. Some are excellent for posting useful tips and resources, and there are often some really experienced and knowledgeable keepers who might be able to answer questions. Conversely, however, please remember that anyone can provide their opinion on these groups, and therefore it is really important to verify what you read. We frequently see illegal, unethical and inappropriate suggestions and practices on these groups due to their lack of regulation. Some group admins are excellent at quashing these, however others can descend into chaos.

Please also remember that only your vet should be consulted for veterinary advice. It is actually illegal for anyone other than a vet to diagnose a disease in an animal,10