Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Atlantic Books

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

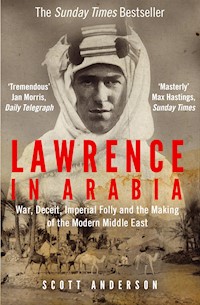

The Sunday Times Top Ten Bestseller 2014 New York Times top ten bestseller 2014 Amazon.com's Top Ten History Books of the Year 2014 New York Times Book of the Year 2014 The Arab Revolt against the Turks in World War One was, in the words of T.E. Lawrence, 'a sideshow of a sideshow'. Amidst the slaughter in European trenches, the Western combatants paid scant attention to the Middle Eastern theatre. As a result, the conflict was shaped to a remarkable degree by a small handful of adventurers and low-level officers far removed from the corridors of power. At the centre of it all was Lawrence. In early 1914 he was an archaeologist excavating ruins in the sands of Syria; by 1917 he was battling both the enemy and his own government to bring about the vision he had for the Arab people. Operating in the Middle East at the same time, but to wildly different ends, were three other important players: a German attaché, an American oilman and a committed Zionist. The intertwined paths of these four young men - the schemes they put in place, the battles they fought, the betrayals they endured and committed - mirror the grandeur, intrigue and tragedy of the war in the desert.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 1328

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Lawrence in Arabia

First published in the United States of America in 2013 by Doubleday,a division of Random House, Inc.

First published in Great Britain in 2014 by Atlantic Books,an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright © Scott Anderson, 2013

The moral right of Scott Anderson to be identified as the authorof this work has been asserted by him in accordance withthe Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced,stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means,electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise,without the prior permission of both the copyright ownerand the above publisher of this book

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Hardback ISBN: 978-1-78239-199-9Trade paperback ISBN: 978-1-78239-200-2E-book ISBN: 978-1-78239-201-9Paperback ISBN: 978-1-78239-202-6

Book design by Maria CarellaFrontispiece photograph copyright © Imperial War Museum (Q58838)Maps designed by John T. Burgoyne

Printed in Great Britain

Atlantic BooksAn Imprint of Atlantic Books LtdOrmond House26–27 Boswell StreetLondonWC1N 3 JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

To the two loves of my life,Nanette and Natasha

Contents

Author’s Note

Maps

Introduction

| Part One |

CHAPTER 1

Playboys in the Holy Land

CHAPTER 2

A Very Unusual Type

CHAPTER 3

Another and Another Nice Thing

CHAPTER 4

To the Last Million

CHAPTER 5

A Despicable Mess

CHAPTER 6

The Keepers of Secrets

CHAPTER 7

Treachery

| Part Two |

CHAPTER 8

The Battle Joined

CHAPTER 9

The Man Who Would Be Kingmaker

CHAPTER 10

Neatly in the Void

CHAPTER 11

A Mist of Deceits

CHAPTER 12

An Audacious Scheme

CHAPTER 13

Aqaba

| Part Three |

CHAPTER 14

Hubris

CHAPTER 15

To the Flame

CHAPTER 16

A Gathering Fury

CHAPTER 17

Solitary Pursuits

CHAPTER 18

Damascus

Epilogue: Paris

Acknowledgments

Notes

Bibliography

Index

Author’s Note

In war, language itself often becomes a weapon, and that was certainly true in the Middle Eastern theater of World War I. For example, while the Allied powers tended to use “the Ottoman Empire” and “Turkey” interchangeably, they displayed a marked preference for the latter designation as the war went on, undoubtedly to help fortify the notion that the non-Turkish populations of the Ottoman Empire were somehow “captive peoples” in need of liberation. Similarly, while early-war Allied documents often noted that Palestine and Lebanon were provinces of Ottoman Syria, that distinction tended to disappear as the British and French made plans to seize those territories in the postwar era. On a more subtle level, all the Western powers, including the Ottoman Empire’s/Turkey’s chief ally in the war, Germany, continued to refer to the city of “Constantinople” (its name under a Christian empire overthrown by the Muslim Ottomans in 1453) rather than the locally preferred “Istanbul.”

As many Middle East historians rightly point out, the use of these Western-preferred labels—Turkey rather than the Ottoman Empire, Constantinople instead of Istanbul—is indicative of a Eurocentric perspective that, in its most pernicious form, serves to validate the European (read imperialist) view of history.

This poses a dilemma for historians focusing on the Western role in that war theater—as I do in this book—since the bulk of their research will naturally be drawn from Western sources. In such a situation, it would seem a writer must choose between clarity and political sensitivity; since I feel many readers would find it confusing if, for example, I consistently referred to “Istanbul” when virtually all cited material refers to “Constantinople,” I have opted for clarity.

I was aided in this decision, however, by the fact that these language distinctions were not nearly so clear-cut at the time as some contemporary Middle East historians contend. Even the wartime leadership of the Ottoman Empire/Turkey frequently referred to the city of “Constantinople,” and also tended to use “Ottoman” and “Turkey” synonymously (see the epigraph from Djemal Pasha in Chapter One). To dwell on all this too long is only to invite more complications. As Ottoman historian Mustafa Aksakal readily concedes in The Ottoman Road to War (pp. x–xi), “it seems anachronistic to speak of an ‘Ottoman government’ and an ‘Ottoman cabinet’ in 1914 when the major players had explicitly repudiated ‘Ottomanism’ and were set on constructing a government by and for the Turks . . .”

In sum, like the principals in this book, I’ve used “Ottoman Empire” and “Turkey” somewhat interchangeably, guided mostly by what sounds right in a particular context, while for simplicity, I refer exclusively to “Constantinople.”

On a different language-related matter, Arabic names can be transliterated in a wide variety of ways. For purposes of consistency, I have adopted the spellings that appear most often in quoted material, and have standardized those spellings within quoted material. In most cases, this adheres to Egyptian Arabic pronunciation. For example, a man named Mohammed al-Faroki, whose surname appeared in different documents of the time also as Faruqi, Farogi, Farookee, Faroukhi, etc., will appear as Faroki throughout. The one exception to this standardizing process involves T. E. Lawrence’s chief Arab ally, Faisal ibn Hussein, consistently referred to as Feisal by Lawrence, but as Faisal by most others, including historians. In this case, I’ve retained ‘Feisal’ in Lawrence’s quotations, but changed all others to the preferred ‘Faisal.’

Also, the use of English punctuation has changed quite dramatically over the past century, and Lawrence in particular had an extremely idiosyncratic—some might say antagonistic—approach to it in his writing. In quotations where I believed the original punctuation might obscure meaning for modern readers, I have adopted the modern norm. These changes apply only to punctuation; no words have been added or deleted from quotations except where indicated by brackets or ellipses.

Finally, two versions of Seven Pillars of Wisdom were published in T. E. Lawrence’s lifetime. The first, a handprinted edition of only eight copies, was produced in 1922 and is commonly referred to as the “Oxford Text,” while a revised edition of approximately two hundred copies was produced in 1926; it is this latter version that is most commonly read today. Since Lawrence made clear that he regarded the Oxford Text as a rough draft, I have quoted almost exclusively from the 1926 version. In those few instances where I’ve quoted from the Oxford Text, the endnote citation is marked “(Oxford).”

Introduction

On the morning of October 30, 1918, Colonel Thomas Edward Lawrence received a summons to Buckingham Palace. The King had requested his presence.

The collective mood in London that day was euphoric. For the past four years and three months, Britain and much of the rest of the world had been consumed by the bloodiest conflict in recorded history, one that had claimed the lives of some sixteen million people across three continents. Now, with a speed that scarcely could have been imagined mere weeks earlier, it was all coming to an end. On that same day, one of Britain’s three principal foes, the Ottoman Empire, was accepting peace terms, and the remaining two, Germany and Austria-Hungary, would shortly follow suit. Colonel Lawrence’s contribution to that war effort had been in its Middle Eastern theater, and he too was caught quite off guard by its rapid close. At the beginning of that month, he had still been in the field assisting in the capture of Damascus, an event that heralded the collapse of the Ottoman army. Back in England for less than a week, he was already consulting with those senior British statesmen and generals tasked with mapping out the postwar borders of the Middle East, a once-fanciful endeavor that had now become quite urgent. Lawrence was apparently under the impression that his audience with King George V that morning was to discuss those ongoing deliberations.

He was mistaken. Once at the palace, the thirty-year-old colonel was ushered into a ballroom where, flanked by a half dozen dignitaries and a coterie of costumed courtiers, the King and Queen soon entered. A low cushioned stool had been placed just before the King’s raised dais, while to the monarch’s immediate right, the Lord Chamberlain held a velvet cushion on which an array of medals rested. After introductions were made, George V fixed his guest with a smile: “I have some presents for you.”

Colonel Lawrence knew precisely what was about to occur. The pedestal was an investiture stool, upon which he was to kneel as the King performed the elaborate, centuries-old ceremony—the laying of the sword on the right and then left shoulder, and the presentation of the insignia of the Order—of conferring a knighthood.

It was a moment Lawrence had long dreamed of. As a boy, he had been obsessed with medieval history and the tales of King Arthur’s court, and his greatest ambition, he once wrote, was to be knighted by the age of thirty. On that morning, his youthful aspiration was about to be fulfilled.

A couple of details added to the honor. Over the past four years, George V had given out so many commendations and medals to his nation’s soldiers that even knighthoods were now generally bestowed en masse; in the autumn of 1918, a private investiture like Lawrence’s was practically unheard of. Also unusual was the presence of Queen Mary. She normally eschewed these sorts of ceremonies, but she had been so stirred by the accounts of T. E. Lawrence’s wartime deeds as to make an exception in his case.

Except Lawrence didn’t kneel. Instead, just as the ceremony got under way, he quietly informed the King that he was refusing the honor.

There followed a moment of confusion. Over the nine-hundred-year history of the monarchy, the refusal of a knighthood was such an extraordinary event that there was no protocol for how to handle it. Eventually, the King returned to the cushion the medal he had been awkwardly holding, and under the baleful gaze of a furious Queen Mary, Lawrence turned and walked away.

TODAY, MORE THAN seven decades after his death, and nearly a century since the exploits that made him famous, Thomas Edward Lawrence—“Lawrence of Arabia,” as he is better known—remains one of the most enigmatic and controversial figures of the twentieth century. Despite scores of biographies, countless scholarly studies, and at least three movies, including one considered a masterpiece, historians have never quite decided what to make of the young, bashful Oxford scholar who rode into battle at the head of an Arab army and changed history.

One reason for the contentiousness over his memory has to do with the terrain he traversed. Lawrence was both eyewitness to and participant in some of the most pivotal events leading to the creation of the modern Middle East, and this is a corner of the earth where even the simplest assertion is dissected and parsed and argued over. In the unending debates over the roots of that region’s myriad fault lines, Lawrence has been alternately extolled and pilloried, sanctified, demonized, even diminished to a footnote, as political goals require.

Then there was Lawrence’s own personality. A supremely private and hidden man, he seemed intent on baffling all those who would try to know him. A natural leader of men, or a charlatan? A man without fear, or both a moral and physical coward? Long before any of his biographers, it was Lawrence who first attached these contradictory characteristics—and many others—to himself. Joined to this was a mischievous streak, a storyteller’s delight in twitting those who believed in and insisted on “facts.” The episode at Buckingham Palace is a case in point. In subsequent years, Lawrence offered several accounts of what had transpired in the ballroom, each at slight variance with the others and at even greater variance to the recollections of eyewitnesses. Earlier than most, Lawrence seemed to embrace the modern concept that history was malleable, that truth was what people were willing to believe.

Among writers on Lawrence, these contradictions have often spurred descents into minutiae, arcane squabbles between those seeking to tarnish his reputation and those seeking to defend it. Did he truly make a particular desert crossing in forty-nine hours, as he claimed, or might it have taken a day longer? Did he really play such a signal role in Battle X, or does more credit belong to British officer Y or to Arab chieftain Z? Only slightly less tedious are those polemicists wishing to pigeonhole him for ideological ends. Lawrence, the great defender of the Jewish people or the raging anti-Semite? The enlightened progressive striving for Arab independence or the crypto-imperialist? Lawrence left behind such a large body of writing, and his views altered so dramatically over the course of his life, that it’s possible with careful cherry-picking to both confirm and refute most every accolade and accusation made of him.

Beyond being tiresome, the cardinal sin of these debates is that they obscure the most beguiling riddle of Lawrence’s story: How did he do it? How did a painfully shy Oxford archaeologist without a single day of formal military training become the battlefield commander of a foreign revolutionary army, the political master strategist who foretold so many of the Middle Eastern calamities to come?

The short answer might seem somewhat anticlimactic: Lawrence was able to become “Lawrence of Arabia” because no one was paying much attention.

Amid the vast slaughter occurring across the breadth of Europe in World War I, the Middle Eastern theater of that war was of markedly secondary importance. Within that theater, the Arab Revolt to which Lawrence became affiliated was, to use his own words, “a sideshow of a sideshow.” In terms of lives and money and matériel expended, in terms of the thousands of hours spent in weighty consultation between generals and kings and prime ministers, the imperial plotters of Europe were infinitely more concerned over the future status of Belgium, for example, than with what might happen in the impoverished and distant regions of the Middle East. Consequently, in the view of British war planners, if a young army officer left largely to his own devices could sufficiently organize the fractious Arab tribes to harass their Turkish enemy, all to the good. Of course, it wouldn’t be very long before both the Arab Revolt and the Middle East became vastly more important to the rest of the world, but this was a possibility barely considered—indeed, it could hardly have been imagined—at the time.

But this isn’t the whole story either. That’s because the low regard with which British war strategists viewed events in the Middle East found reflection in the other great warring powers. As a result, these powers, too, relegated their military efforts in the region to whatever could be spared from the more important battlefields elsewhere, consigning the task of intelligence gathering and fomenting rebellion and forging alliances to men with résumés just as modest and unlikely as Lawrence’s.

As with Lawrence, these other competitors in the field tended to be young, wholly untrained for the missions they were given, and largely unsupervised. And just as with their more famous British counterpart, to capitalize on their extraordinary freedom of action, these men drew upon a very particular set of personality traits—cleverness, bravery, a talent for treachery—to both forge their own destiny and alter the course of history.

Among them was a fallen American aristocrat in his twenties who, as the only American field intelligence officer in the Middle East during World War I, would strongly influence his nation’s postwar policy in the region, even as he remained on the payroll of Standard Oil of New York. There was the young German scholar who, donning the camouflage of Arab robes, would seek to foment an Islamic jihad against the Western colonial powers, and who would carry his “war by revolution” ideas into the Nazi era. Along with them was a Jewish scientist who, under the cover of working for the Ottoman government, would establish an elaborate anti-Ottoman spy ring and play a crucial role in creating a Jewish homeland in Palestine.

If little remembered today, these men shared something else with their British counterpart. Like Lawrence, they were not the senior generals who charted battlefield campaigns in the Middle East, nor the elder statesmen who drew lines on maps in the war’s aftermath. Instead, their roles were perhaps even more profound: it was they who created the conditions on the ground that brought those campaigns to fruition, who made those postwar policies and boundaries possible. History is always a collaborative effort, and in the case of World War I an effort that involved literally millions of players, but to a surprising degree, the subterranean and complex game these four men played, their hidden loyalties and personal duels, helped create the modern Middle East and, by inevitable extension, the world we live in today.

Yet within this small galaxy of personalities there remain at least two compelling reasons why T. E. Lawrence and his story should reside firmly at its center.

The modern Middle East was largely created by the British. It was they who carried the Allied war effort in the region during World War I and who, at its close, principally fashioned its peace. It was a peace presaged by the nickname given the region by covetous Allied officials in wartime: “the Great Loot.” As one of Britain’s most important and influential agents in that arena, Lawrence was intimately connected to all, good and bad, that was to come.

Second, and as the episode at Buckingham Palace attests, this was an experience that left him utterly changed, unrecognizable in certain respects even to himself. Victory carries a moral burden the vanquished never know, and as an architect of momentous events, Lawrence would be uniquely haunted by what he saw and did during the Great Loot.

Part One

Chapter 1

Playboys in the Holy Land

I consider this new crisis that has emerged to be a blessing. I believe that it is the Turks’ ultimate duty either to live like an honorable nation or to exit the stage of history gloriously.

DJEMAL PASHA, GOVERNOR OF SYRIA,ON TURKEY’S ENTRY INTO WORLD WAR I, NOVEMBER 2, 1914

The storm began as a mild weather disturbance, one fairly common for that time of year. For several days in early January 1914, a hot dry breeze had come off the Sahara Desert to pass over the winter-cooled waters of the eastern Mediterranean. By the morning of the ninth, this convergence had spawned a strong southwesterly wind, one that grew in intensity as it made landfall over southern Palestine. By the time it approached Beersheva, a small village on the edge of the Zin Desert some twenty-five miles inland, this wind threatened to trigger a khamsin, or sandstorm.

For the inexperienced, being caught out in the desert during a khamsin can be unsettling. While it shares some of the properties of a severe thunderstorm—the same drop in barometric pressure beforehand, the same prelude of buffeting wind—the fact that sand is falling rather than water means visibility can rapidly drop to just a few feet, and the constant raking of sand against the body, coating the nose and mouth and collecting in every crevice of clothing, can induce a feeling of suffocation. In the grip of this sensation, the mind can easily seize upon the worst idea—to journey on, to attempt to fight one’s way out of the storm. Men routinely become lost and die acting on this impulse.

But the three young British men waiting in Beersheva that afternoon were not inexperienced. They had lingered an extra day in the village—a lonely outpost of perhaps eight hundred inhabitants best known as a watering hole for passing camel caravans—in expectation of the arrival of an expedition party led by two Americans. By dusk, however, there was still no sign of the Americans, and what had earlier appeared no more threatening than a dull brown haze in the west had now formed up into a mile-high wall of approaching sand. Shortly after dark, the khamsin rolled in.

Throughout that night, the storm raged. In the small house the British men shared, sand spattered against the shuttered windows like driven rain, and all their efforts to seal the place couldn’t prevent them and everything else inside from becoming coated in a fine layer of desert dust. By dawn, the winds had abated somewhat, enough that the risen sun appeared as a pale silvery orb in the eastern sky.

The khamsin finally died off in early afternoon, allowing the residents of Beersheva to emerge from their homes and tents and move about. It was then that the Britons received some news of the Americans. Apparently caught out by the impending storm, they had drawn camp the previous evening in the desert just a few miles east of town. The three men saddled their camels and made for the American camp.

Considering the surrounding desolation, the opulence they found there made for a rather bizarre spectacle. Along with a couple of horse-drawn carts hauling silage for the party’s herd of pack animals were several more to carry its larger “field furniture.” Now that the khamsin had passed, the native orderlies were busily breaking camp, including dismantling the two very fine and spacious Bell tents—undoubtedly purchased from one of the better expedition outfitters in London or New York—that were the habitations of the two young Americans leading the expedition. These men, both in their midtwenties and clad in Western field suits and bowler hats, were named William Yale and Rudolf McGovern. As they explained to their British visitors, they were in southern Palestine as part of a Grand Tour of the Holy Land, an adventure that when the sandstorm hit had become a bit more than they bargained for.

But there was something about the Americans that didn’t quite add up. Although they were well dressed and obviously traveling in high style, there was little about the men—McGovern small and reserved, Yale barrel-chested with a boxer’s rough-hewn face—that suggested them as either natural traveling companions or likely candidates for a pilgrimage tour of biblical sites. Then there was their demeanor. Encountering other foreigners in this lonely corner of Syria was such a novelty that it tended to induce a kind of instant camaraderie, but there was none of this with Yale and McGovern. To the contrary, the Americans appeared flustered, even perturbed, by the arrival of the Britons, and it seemed that only the dictates of desert hospitality compelled Yale—clearly the dominant personality of the two—to invite their guests into the main dining tent and to dispatch one of their camp followers to prepare tea.

But if the Americans seemed peculiar, William Yale had precisely the same reaction to his British visitors. The oldest—and the leader of the group, in Yale’s estimation—was a dark-haired, hawk-faced man in his midthirties clad in a well-worn British army uniform. His companions were in civilian dress and quite a bit younger, one in his midtwenties perhaps, while the third appeared to be a mere teenager. Most puzzling to Yale, the two older men barely spoke. Instead, it was the “teenager” who commandeered the conversation in the tent and chattered like a magpie. He was very slight and slender, with a heavy-featured face that Yale found almost repellent, but his most arresting feature was his eyes; they were light blue and piercingly intense.

The young visitor explained that he and his companions were in the region to conduct an archaeological survey of biblical-era ruins for a British organization called the Palestine Exploration Fund. He then proceeded to regale his American hosts with stories of his own adventures in the Near East, stories so voluble and engaging that it took Yale quite some time to realize they masked a kind of interrogation.

“His chatter was sprinkled with a stream of questions—seemingly quite innocent questions—about us and our plans. He assumed that we were tourists traveling in grand style to see the famous ruins of the Sinai and Palestine. It was not until after our visitors had left that we realized that this seemingly inexperienced, youthful enthusiast had most successfully pumped us dry.”

It would be some time before he knew it, but William Yale had just had his first encounter with Thomas Edward Lawrence, soon to become better known as Lawrence of Arabia. It would also be some time before he learned that Lawrence had only feigned interest in the Americans’ Holy Land tour in order to toy with them, that he had known all along their story was false.

In reality, William Yale and Rudolf McGovern were agents of the Standard Oil Company of New York, and they were in Palestine on a secret mission in search of oil. Under orders from Standard headquarters, they had spent the previous three months posing as wealthy young men of leisure—“playboys,” in the parlance of the day—on the Holy Land tourist circuit. While upholding that cover story, they had quietly slipped off to excavate along the Dead Sea and to take geological soundings in the Judean foothills.

But if the playboy tale had held the ring of plausibility during their earlier wanderings—at least Judea had ruins and the Dead Sea figured prominently in the Bible—it became rather suspect once they veered off for the forlorn outpost of Beersheva. It was downright laughable when considering Yale and McGovern’s ultimate destination: a desolate massif of stone rising up out of the desert some twenty miles southeast of Beersheva known as Kornub.

In fact, it was not the khamsin but the growing improbability of their cover story that had kept the Americans out of Beersheva the night before. As they had approached the village, the oilmen had been alerted to the presence of the three Britons. Anxious to avoid a meeting and the awkward questions likely to arise, they had chosen to pitch camp in the desert instead, with the intention of slipping into Beersheva at first light, quickly gathering up supplies for their onward journey, and stealing away before being detected. The slow-moving khamsin had obviously put an end to that plan, and as he’d waited out the storm that morning, Yale had feared it was only a matter of time before the foreigners in Beersheva learned of their desert campsite and put in an appearance—an apprehension confirmed when the three men rode up.

But what Yale also couldn’t have known was that his efforts at concealment were quite pointless, that this seemingly impromptu meeting in the desert was anything but. The previous day, Lawrence and his colleagues on the archaeological expedition had received a cable from the British consulate in Jerusalem alerting them to the presence of the American oilmen in the area, and they had lingered in Beersheva for the express purpose of intercepting Yale and McGovern and learning what they were up to.

If this seemed an odd mission for an archaeological survey team to undertake, there was rather more to that story, too. Although it was technically true that Lawrence and Leonard Woolley—the other civilian in the tent, and a respected archaeologist—were in southern Palestine in search of biblical ruins, that project was merely a fig leaf for a far more sensitive one, an elaborate covert operation being run by the British military. Ottoman government officials certainly knew of the Palestine Exploration Fund survey in the Zin Desert—they had approved it, after all—but they knew nothing of the five British military survey teams operating under the PEF banner who at that very moment were scattered across the desert quietly mapping the Ottoman Empire’s southwestern frontier. Overseeing that covert operation was the uniformed third visitor to the American camp, Captain Stewart Francis Newcombe of the Royal Engineers.

What had taken place outside Beersheva, then, was a rather complex game of bluff, one in which one side had rummaged about for the truth behind the other’s fiction, even as it sought to uphold its own framework of fiction.

LAWRENCE AND YALE weren’t the only young foreigners with suspect agendas wandering about the Holy Land that mid-January. Just fifty miles to the north of Beersheva, in the city of Jerusalem, a thirty-three-year-old German scholar named Curt Prüfer was also plotting his future.

In Prüfer’s physical appearance were few clues to suggest him as an intriguing figure. Quite to the contrary. The German stood just five foot eight, with narrow, sloping shoulders, and his thin thatch of brownish blond hair framed a bland, thin face most noteworthy for its lack of distinguishing characteristics, the sort of face that naturally blends into a crowd. Adding to this air of innocuousness was Prüfer’s voice. He spoke in a permanent soft, feathery whisper, as if he’d spent his entire life in a library, although this condition was actually the result of a botched throat operation in childhood that had scarred his vocal cords. To many who met the young German scholar, his modest frame together with that voice conveyed an aura of effeminacy, an estimation likely to be fortified should they happen to learn the subject of the dissertation that had earned him his doctorate: a learned study on the Egyptian dramatic form known as shadow plays. In mid-January 1914, Prüfer was waiting in Jerusalem for the arrival of a friend, a Bavarian landscape painter of middling repute, with whom he’d made plans to conduct an extended tour of the Upper Nile aboard a luxury dhow.

But just as with the men gathered in the tent outside Beersheva, there was an altogether different side to Dr. Curt Prüfer. For the previous several years, he had served as the Oriental Secretary to the German embassy in Cairo, a position ideally suited to both his appearance and demeanor. Removed from the policymaking deliberations of the senior diplomatic staff, the Oriental Secretary was tasked to quietly keep tabs on the social and political undercurrents of the country, to maintain a low profile and report back. In that capacity, Prüfer’s life in Cairo had been a never-ending social whirl, a perpetual roster of meetings and teas and dinners with Egypt’s most prominent journalists, businessmen, and politicians.

His social circle had included more controversial figures, too. With Germany vying with its rival, Britain, for influence in the region, Prüfer had surreptitiously cultivated alliances with a wide array of Egyptian dissidents seeking to end British control of their homeland: nationalists, royalists, religious zealots. Fluent in Arabic as well as a half dozen other languages, in 1911 the German Oriental Secretary had traveled across Egypt and Syria disguised as a Bedouin to foment anti-British sentiment among the tribes. The following year, he had attempted to recruit Egyptian mujahideen to join their Arab brethren in Libya against an invading Italian army.

In these varied efforts, Curt Prüfer had eventually fallen foul of the first rule of his position: to stay in the background. Alerted to his agent provocateur activities, the British secret police in Egypt had quietly compiled a lengthy dossier on the Oriental Secretary, and bided their time on when to use it. When finally they did, Prüfer was effectively persona non grata. After enduring the ignominy for as long as he could, he had tendered his resignation from the German diplomatic service in late 1913. It was this that had brought him to Jerusalem that January. Once his friend, the artist Richard von Below, arrived from Germany, the two would depart for Egypt and their luxury cruise up the Nile. That journey was scheduled to last some five months, and while von Below painted, Prüfer intended to busy himself composing travelogue articles for magazines back in Germany, along with updating entries for the famous German travel guide, Baedeker’s. It was to mark something of a return to Prüfer’s academic roots, his extended foray into the messy arena of international politics consigned to the past.

Or maybe not. Maybe his spying activities were just put on hold, for on his upcoming cruise, Curt Prüfer would be traveling along the very lifeline of British-ruled Egypt, would be given the opportunity to glimpse firsthand its defensive fortifications and port facilities, to quietly take the pulse of Egyptian public opinion. And while it might appear that the exposed and disgraced former Oriental Secretary was sailing into an unsettled future that January of 1914, he now held at least one conviction that gave his life a strong sense of direction: it was the British who had destroyed his diplomatic career; it was the British upon whom he would take his revenge.

Toward achieving this, he could draw on another rather surprising aspect of his personality. His aura of innocuousness notwithstanding, Curt Prüfer was a consummate charmer, and had a reputation as a notorious seducer of women. In Cairo, whatever affections he felt for his wife, a doughty American woman thirteen years his senior, had been shared between a string of mistresses. Since arriving in Jerusalem, he had taken up with a young and beautiful Russian Jewish émigré doctor named Minna Weizmann, better known to her friends and family as Fanny. In just a little over a year’s time, as Germany’s counterintelligence chief in wartime Syria, Prüfer would come up with the idea of recruiting Jewish émigrés to infiltrate British-held Egypt and spy for the Fatherland. Among the first spies Prüfer would send into enemy territory would be his lover, Fanny Weizmann.

. . .

JUST SEVENTY MILES to the north of Jerusalem that January, there was another man about to embark on a double life. His name was Aaron Aaronsohn. A thirty-eight-year-old Jewish émigré from Romania, Aaronsohn was already recognized as one of the preeminent agricultural scientists, or agronomists, in the Middle East, a reputation cemented by his 1906 discovery of the genetic forebear to wheat. With funding from American Jewish philanthropists, in 1909 he had established the Jewish Agricultural Experiment Station outside the village of Athlit, and for the past five years had tirelessly experimented with all manner of plants and trees in hopes of returning the arid Palestinian region of Syria to the verdant garden it had once been.

This ambition had a political component. A committed Zionist, as early as 1911 Aaronsohn had begun to articulate a scheme whereby a vast swath of Palestine might be wrested away from the Ottoman Empire and reconstituted as a Jewish homeland. Other Zionists had expressed this vision before, of course, but it was Aaronsohn, with his encyclopedic knowledge of the region’s flora and soil conditions and aquifers, who first appreciated how it might practically be accomplished, how the Jewish diaspora might return to its ancestral homeland and prosper by making the desert bloom.

In the near future, Aaronsohn would perceive the chance to bring this dream closer to fruition, and he would seize it. Under the cover of advising the local government on agricultural matters, he would establish an extensive spy ring across the breadth of Palestine, and provide the Ottomans’ British enemies with some of their most invaluable battlefield intelligence. The agronomist would then go on to play a signal role in promoting the cause of a Jewish homeland in the capitals of Europe. Somewhat ironically, his chief confederate in that endeavor would be the older brother of Curt Prüfer’s lover-spy, Fanny Weizmann, and the future first president of Israel: Chaim Weizmann.

THE LURE OF the East: whether to conquer or explore or exploit, it has exerted its pull on the West for a thousand years. That lure brought wave after wave of Christian Crusaders to the Near East over a three-hundred-year span in the Middle Ages. More recently, it brought a conquering French general with pharaonic fantasies named Napoleon Bonaparte to Egypt in the 1790s, Europe’s greatest archaeologists in the 1830s, and hordes of Western oil barons, wildcatters, and con men to the shores of the Caspian Sea in the 1870s. For a similar variety of reasons, in the early years of the twentieth century it brought together four young men of adventure: Thomas Edward Lawrence, William Yale, Curt Prüfer, and Aaron Aaronsohn.

At the time, the regions these men traveled were still a part of the Ottoman Empire, one of the greatest imperial powers the world had ever known. From its birthplace in a tiny corner of the mountainous region of Anatolia in modern-day Turkey, that empire had steadily expanded until by the early 1600s it encompassed an area rivaling that of the Roman imperium at its height: from the gates of Vienna in the north to the southern tip of the Arabian Peninsula, from the shores of the western Mediterranean clear across to the port of Basra in modern-day Iraq.

But that had been then. By the second decade of the twentieth century, the Ottoman Empire had long been in a state of seemingly terminal decline. The proverbial “sick man of Europe,” its epitaph had begun to be written as far back as the 1850s, and in the intervening years no fewer than five of the imperial powers of Europe had taken turns snatching away great swaths of its territory. That the Ottomans had managed to avoid complete destruction thus far was due both to their skill at playing off those competing European powers and to no small measure of improbable good luck. In 1914, however, all that was about to change. By guessing wrong—very wrong—in the calamitous war just then descending, the Ottomans would not only bring on their own doom but unleash forces of such massive disintegration that the world is still dealing with the repercussions a century later.

Chapter 2

A Very Unusual Type

Can you make room on your excavations next winter for a young Oxford graduate, T. Lawrence, who has been with me at Carchemish? He is a very unusual type, and a man whom I feel quite sure you would approve of and like. . . . I may add that he is extremely indifferent to what he eats or how he lives.

DAVID HOGARTH TO EGYPTOLOGIST FLINDERS PETRIE, 1911

“I think it time I dedicated a letter to you,” Thomas Edward Lawrence wrote his father on August 20, 1906, “although it does not make the least difference in style, since all my letters are equally bare of personal information. The buildings I try to describe will last longer than we will, so it is only fitting that they should have the greater space.”

True to his word, Lawrence spent the rest of that letter imparting absolutely no information about himself, not even bothering to mention how he had spent his eighteenth birthday four days earlier. Instead, he used the space to describe in minute detail the structural peculiarities of a fourteenth-century castle he had just visited.

Lawrence, on holiday from the City of Oxford High School for Boys, was spending that summer bicycling through northwestern France. The bicycle had only recently become widely available to the European general public, a result of design innovations and mass production, and it had sparked something of a craze among the British middle class for cycling tours of the European countryside. Lawrence’s trip was on a wholly different scale, however: a nearly thousand-mile trek that took him to most every notable castle and cathedral in the Normandy region.

The notes he took of these places formed the basis of Lawrence’s letters to his family back in Oxford. While he often prefaced them with brief expressions of concern for his mother’s purportedly frail health, the chief characteristic of most of his correspondence was its utter impersonality, the same disquisitional tone as adopted in that to his father.

In some respects, this element of emotional constriction was probably not unusual for a member of a British middle-class family at the end of the Victorian age. It may have been heightened in the Lawrence household by its male preponderance—a family of five boys and no girls—but this was a segment of society that prized self-control and understatement, where children were expected to be studious and respectful, and where a parent’s greatest gift to those children was not an indulgent affection but rather a sober religious grounding and a good education. It was also a segment of society that held to a simple and comfortable worldview. While radical political ideas were starting to find flower among the working class, the British middle class still adhered to a social hierarchy based less on attained wealth than on ancestry and accent, a caste system that rigidly dictated nearly every aspect of social life—in some respects, even more rigidly than a half century before. If stultifying, this stratification also meant that everyone knew his place, the station in life to which he might reasonably aspire. To the degree possible, social and economic advancement was obtained through the “godly virtues” of modesty, self-reliance, diligence, and thrift.

Perhaps the least questioned tenet of the time was the notion that the British Empire now stood at the very apex of modern civilization, and that it was the special burden of this empire to spread its enlightenment—whether through commerce, the Bible, the gun, or some combination of all three—to the world’s less fortunate cultures and races. While this conviction extended to all segments of British society, it had special resonance for the middle class, since it was from precisely this social stratum that the chief custodians of empire—its midlevel military field officers and colonial administrators—were drawn. This, too, undoubtedly contributed to an emotional distance in such families; from the time of their children’s birth, parents had to steel themselves to the likelihood that some of their offspring, especially the males, might ship out to a remote outpost of empire, not to be seen again for decades, if ever.

It is perhaps not surprising, then, that the British middle-class generation coming of age in the early 1900s was marked by a certain blitheness, so much so that in recalling their growing up many years later, one of Lawrence’s brothers could write without a hint of irony, “We had a very happy childhood, which was never marred by a single quarrel between any of us.”

But in at least one respect, there was something altogether unusual about the Lawrence family on Oxford’s Polstead Road, and it undoubtedly added to the emotional austerity in that household. Quite unbeknownst to the neighbors and to most of their own children, Thomas and Sarah Lawrence were harboring a scandalous secret: they were essentially living as fugitives. The key to that secret began with the family surname, which wasn’t really Lawrence.

Thomas Lawrence’s real name was Thomas Robert Tighe Chapman, and in his prior incarnation he had been a prominent member of the Anglo-Irish landed aristocracy. After being educated at Eton, the future baronet had returned to Ireland and, in the early 1870s, took up the pleasant role of gentleman farmer of his family’s estate in County Westmeath. He married a woman from another wealthy Anglo-Irish family, with whom he soon had four daughters.

But Chapman’s gilded existence began to unravel when he started an affair with the governess to his young daughters, a twenty-four-year-old Scottish woman named Sarah Junner. By the time Chapman’s wife learned of the affair in early 1888, Sarah already had one child with Thomas—an infant son secreted in a rented apartment in Dublin—and a second was on the way. Refused a divorce by his wife, the aristocrat was forced to choose between his two families.

Given the laws and moral strictures of the Victorian era, the consequences of that choice could hardly have been more profound. If he opted to stay with Sarah Junner, Thomas Chapman would not only be stripped of most of his family inheritance, but his four daughters would have great difficulty ever marrying due to the taint of family scandal. Worse was what would lie in store for his and Sarah’s offspring. As illegitimates, they would be effectively barred from many of the better schools and higher professions that, had they been legally born to the Chapman name, would be their birthright. Certainly, the most prudent course was for Thomas to bundle Sarah back to her native Scotland with a supporting stipend for herself and her children, a rather common arrangement of the day when servant girls got “into trouble” with their masters. Instead, Chapman chose to stay with Sarah.

After renouncing his claim to the family fortune in favor of his younger brother, Thomas left Ireland with Sarah in mid-1888 for the anonymity of a small village in northern Wales called Tremadoc. There, the couple assumed the alias of Sarah’s mother’s maiden name, Lawrence, and in August of that year Sarah gave birth to their second child, a son they named Thomas Edward.

But Wales brought the couple no peace of mind. Getting by on a modest annuity from the Chapman family estate but living in constant fear that they might one day encounter someone who knew them from their former lives, the Lawrences began a furtive, peripatetic existence: Tremadoc was soon given up for an even more remote village in northern Scotland, then it was on to the Isle of Man, followed by a couple of years in a small French town, followed by two more years in a secluded hunting lodge on the south coast of England. Compounding the isolation in these places—in each, the Lawrences rented homes on village outskirts or surrounded by high stone walls—Thomas severed ties to nearly all his former friends, while Sarah rarely left the security and anonymity of the family home.

“You can imagine how your mother and I have suffered all these years,” Thomas Lawrence would confide in a posthumous letter to his sons, “not knowing what day we might be recognized by some one and our sad history published far and wide.”

In light of this driving fear, the Lawrences’ decision to move to Oxford in 1896 must have been a downright harrowing one. For the first time, the couple would not only be living in the center of a large town but, given Thomas’s aristocratic and educational background, in a place where it was very likely they would cross paths with someone from their past. But against this was the opportunity for their sons—now grown to four in number, with a fifth on the way—to receive a good education, maybe even to be admitted to one of the Oxford colleges, and so the Lawrences took the gamble. The price for this heightened exposure, however, was a family drawn even tighter into itself, the boys’ lives circumscribed in comparison to those of their classmates, but for reasons those boys couldn’t begin to fathom. All except Thomas Edward, that is. With the move to Oxford, the eight-year-old was now settling into the sixth home of his young life, and at some point during his first years at Polstead Road he partially unraveled the family secret. He kept the information to himself, however, never confronting his parents nor confiding in any of his brothers.

At the City of Oxford High School for Boys, Lawrence was known as an exceptionally bright but quiet student, one for whom team sports held no appeal and who, if not engaged in a solitary pursuit, preferred the company of his brothers or just a very small group of close friends. His bookish side—he had been a voracious reader even as a young child—was offset by a love of bicycle riding and a fondness for practical jokes. But there was something else as well. By early adolescence, “Ned,” as he was known to family and friends, had developed the habit of constantly testing the limits of his endurance, whether in how far or fast he could bicycle or how long he could go without food or sleep or water. This wasn’t the usual stuff of boyhood self-testing, but protracted ordeals that, through a kind of iron will, Ned could sustain to the point of collapse. So pronounced was this tendency that even his headmaster in the fourth form (equivalent to American eighth grade) took notice: “He was unlike the boys of his time,” Henry Hall wrote in a remembrance of Lawrence, “for even in his schooldays he had a strong leaning toward the Stoics, an apparent indifference towards pleasure or pain.”

Some of this may have stemmed from an increasingly severe home environment. As the Lawrence boys grew older, Sarah, the disciplinarian of the family, became both more religious and more given to physical punishment. These were not mere spankings, but rather protracted whippings with belts and switches, and in the remembrance of the Lawrence boys, Ned was by far her most frequent target. It established a disturbing pattern between mother and son. That Ned made a point of never crying or asking for leniency during these whippings—to the contrary, he seemed to derive satisfaction from his ability to display no emotion whatsoever—often had the effect of making the punishments worse, so much so that on several occasions the normally cowed Thomas Lawrence intervened to put a stop to them.

At around the age of fifteen, Ned abruptly stopped growing. With his brothers all eventually surpassing him in height, he became acutely aware of his shortness—variously pegged at between five foot three and five foot five—and this seemed to deepen an already pronounced shyness. About the same time, he developed a fascination with the tales of medieval knights, and with archaeology. He began taking long bicycle trips to churches in the English countryside, where he would conduct brass rubbings of memorial plaques. With his best friend of the time, he scoured the construction sites of new buildings going up in Oxford in search of old relics, and came upon a good number of them. These finds, mostly glass and pottery shards from the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, soon led Ned to the Ashmolean Museum in central Oxford.

With the distinction of being the oldest public museum in Britain, and with an emphasis on charting the confluence of Eastern and Western cultures, the Ashmolean was to play a transformative role in Lawrence’s life. Encouraged by its curators to whom he brought his construction site finds, the teenager soon became a familiar figure around the museum, dropping in after school, helping with odd chores on the weekends. For Lawrence, the Ashmolean became a window onto the world that lay beyond Oxford, its artifacts giving physicality to all the places and civilizations he constantly read about. Testament to his fascination with the past, as well as his already fierce streak of self-sufficiency, was that extended bicycle tour of the castles and cathedrals of Normandy in the summer of 1906.

Earning high marks at school, in the autumn of 1907 Lawrence was admitted to Jesus College, Oxford, there to read history. With an abiding interest in both military history and the Middle Ages, he fashioned a thesis focusing on the architecture of medieval castles and fortifications. To that end, for the summer of 1908 recess, he plotted a journey that dwarfed his earlier excursion to Normandy, an elaborate 2,400-mile bicycle trek that would take him to nearly every significant such structure across the breadth of France. Staying in cheap pensions, or camping in the rough, he routinely pedaled more than a hundred miles a day as he went from one ancient castle or battlement to the next. At each, he took photographs, made sketches, and wrote up exhaustive notes before getting back on his bicycle and pedaling on.

Initially, his letters back to Polstead Road assumed the same dry, even tedious tone of those from his earlier travels. But then something changed. It happened on August 2, 1908, when Lawrence reached the village of Aigues-Mortes and he saw the Mediterranean Sea for the first time. In the letter home describing that day, Lawrence displayed an exuberance and sense of wonder that was quite out of character.

“I bathed today in the sea,” he wrote, “the great sea, the greatest in the world; you can imagine my feelings. . . . I felt that at last I had reached the way to the South, and all the glorious East—Greece, Carthage, Egypt, Tyre, Syria, Italy, Spain, Sicily, Crete—they were all there, and all within reach of me. . . . Oh I must get down here—farther out—again! Really this getting to the sea has almost overturned my mental balance; I would accept a passage for Greece tomorrow.”

It was almost as if he were describing a religious epiphany. In a way, he was.

When Lawrence returned to Oxford and his studies that autumn, he began to hatch a new—and infinitely more ambitious—journey, one that would take him to the furthermost region of those he had contemplated that day in Aigues-Mortes. Among the first to hear of this new scheme was a man named David Hogarth.

A noted archaeologist who had worked and traveled extensively in the Near East, Hogarth had only recently taken up the position of director, or keeper, of the Ashmolean Museum. From the Ashmolean’s assistant curators he had undoubtedly heard mention of T. E. Lawrence—that the shy Oxford student had been a fixture around the museum since his early teens, that he showed a keen curiosity in archaeological work—but this did not at all prepare Hogarth for the diminutive figure ushered into his office one day in January 1909.

After his tour of the castles in France, Lawrence had now radically expanded the idea for his BA thesis at Oxford. Put simply, there just wasn’t much new to be said or discovered by examining European medieval fortifications in isolation, whereas one of the enduring mysteries in the study of military architecture was the degree to which innovations in medieval battlements were of Western or Eastern origin: had the Christian Crusaders learned from their Muslim enemies while invading the Holy Land, or had the Muslims copied from the Crusaders? As Lawrence explained to Hogarth, what he proposed was a comprehensive survey of the Crusader castles of the Syrian Near East—and, in typical Lawrence fashion, not merely a visit to some of the more notable ones, but a tour of practically all of them. Lawrence planned to make this trek during the next Oxford summer recess, and alone.

Hogarth, already thrown by Lawrence’s modest stature—he was now twenty but could easily pass for fifteen—was aghast at the plan. The expedition Lawrence proposed meant a journey of well over a thousand miles across deserts and rugged mountain ranges, where whatever roads and trails existed had only deteriorated since Roman times. What’s more, summer was the absolute worst time to travel in Syria, a season when temperatures routinely reached 120 degrees in the interior. As Hogarth recounted the conversation to a Lawrence biographer, when he tried to diplomatically raise these issues, he was met with a steely resolve.

“I’m going,” Lawrence said.

“Well, have you got the money?” Hogarth asked. “You’ll want a guide and servants to carry your tent and baggage.”

“I’m going to walk.”

The scheme was becoming more preposterous all the time. “Europeans don’t walk in Syria,” Hogarth explained. “It isn’t safe or pleasant.”

“Well,” Lawrence said, “I do.”

Startled by the young man’s brusque determination, Hogarth implored him to at least seek the counsel of a true expert. This was Charles Montagu Doughty, an explorer who had traversed much of the region Lawrence proposed to visit, and whose book Travels in Arabia Deserta remained the definitive travelogue of the time. When contacted, Doughty was even more dismissive of the plan than Hogarth.

“In July and August the heat is very severe by day and night,” he wrote Lawrence, “even at the altitude of Damascus (over 2,000 feet). It is a land of squalor, where a European can find little refreshment. Long daily marches on foot a prudent man who knows the country would, I think, consider out of the question. The populations only know their own wretched life and look upon any European wandering in their country with at best a veiled ill will.”

In case he hadn’t sufficiently made his point, Doughty continued, “The distances to be traversed are very great. You would have nothing to draw upon but the slight margin of strength which you bring with you from Europe. Insufficient food, rest and sleep would soon begin to tell.”

Such counsel might have dissuaded most people, but not Lawrence. For a young man already driven to test the very limits of his endurance, Doughty’s letter read like a dare.

HE CERTAINLY LOOKED the part. With his bull shoulders, calloused hands, and Teddy Roosevelt handlebar mustache, William Yale, the new engineering level-man hired to work on the Culebra Cut in the summer of 1908, blended right in with the tens of thousands of other workers who had descended upon the jungles of Central America. They had come to take part in the most ambitious construction project in the history of mankind, the building of the Panama Canal.

Few of his coworkers might have guessed that in fact William Yale had no engineering background at all; instead, he had obtained the position of level-man, and the premium salary it garnered, through the efforts of a well-connected college friend. Surely even fewer might have guessed that the twenty-one-year-old—by all accounts a tireless and uncomplaining worker—was operating in an environment utterly alien to him, that as a scion of one of America’s wealthiest and most illustrious families he had until very recently lived a life of privilege extraordinary even by the excessive standards of the day. To the American archetype of the self-made man, William Yale represented the dark and polar opposite, one born to tremendous advantage but who had lost it all in the blink of an eye.

Dating their arrival in America to the mid-1600s, the Yales of New England were a quintessential Yankee blueblood family, one that for 250 years had built an ever greater fortune through shipping, manufacturing, and exploiting all the riches the New World had to offer. True to their Presbyterian ethos, the Yales were also a family that believed in good works and education; in 1701, Elihu Yale, William’s great-great-uncle, helped found the university in New Haven that still bears the family name.

Born in 1887, William certainly appeared destined to live in the familial tradition. The third son of William Henry Yale, an industrialist and Wall Street speculator, he grew up on a four-acre estate in Spuyten Duyvil, the bluff at the southwestern tip of the Bronx in New York City. With its commanding views of both Manhattan and the Hudson River, Spuyten Duyvil had long been favored by New York’s moneyed class seeking to escape the noise and grime of the city, and the Yale estate was among the grandest. Through early childhood, William and his siblings, four brothers and two sisters, were educated by private tutors at the family mansion, took dance and social etiquette classes at Dodsworth’s, Manhattan’s preeminent dancing academy, and spent summers at the family’s vast forested estate in the Black River valley of upstate New York. Like his two older brothers before him, for high school William was shipped off to the prestigious Lawrenceville School outside Princeton.

But even from an early age, the Yale boys probably had broader horizons than most other male offspring of the New York pampered set. This was due to their father. Beyond being an ardent political supporter of Teddy Roosevelt—the Yales fit squarely into the progressive Republican mold—William Henry Yale also subscribed to Roosevelt’s notions of the ideal American man and of the dangers of “over-civilization,” code for effeminacy. The true man, in this worldview, was a rugged individualist, physically fit as well as intellectually cultured, as equally at home leading men into battle or shooting big game on the prairie as chatting with the ladies in the salon. To this end, William Henry frequently took his sons on extended trips into the American wilderness and ensured that they were just as adept at hunting, fishing, and trapping as in displaying the proper manners at a Spuyten Duyvil garden party.