Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Crown House Publishing

- Kategorie: Bildung

- Sprache: Englisch

The first book to focus on the application of language models for classroom management, Making Your Words Work offers a large repertoire of linguistic approaches to improve communication between teacher and pupil. It provides a robust rationale of the causes of anxiety and dysfunctional behaviour. It covers the latest developments in effective teaching through the modification of language use. Previously published as Words Work!: How to Change Your Language to Improve Behaviour in Your Classroom ISBN 978-189983698-7 - resized and reformatted.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 296

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2007

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Making Your Words Work!

Using NLP to Improve Communication, Learning & Behaviour

Terry Mahony

For Danielle and Katherine, who both prompted and contributed to this book

Table of Contents

Title Page

Dedication

Preface

Introduction

Part I: What Am I Going to Learn?

Chapter One General Elements of NLP

The NLP mindset: guiding principles for excellent behaviour managers

Some of the key elements of NLP

1. The simple NLP communication model

2. The levels of meaning

3. Motivational patterns

Key conclusions

Sources and further reading for this chapter

Chapter Two Mind your Language!

Patterns of language

Personally preferred speech patterns

Learning from experience

Visual

Auditory-tonal

Auditory-digital

Kinaesthetic

War and peace – rapport and disharmony

Ways of improving rapport

Linguistic harmony

Conflict and disharmony

Regaining rapport – mediation

“What makes this pupil tick?” – strategies in NLP

Key conclusions

Sources and further reading for this chapter

Part II: Why Should I Learn This?

Chapter Three What’s Happening in Classrooms Now?

Managing behaviour

Discipline versus counselling

The psychology of behaviour and learning – a toolkit of ideas and practices

Brain research

Emotional intelligence – for you and them

The teacher as coach

Key conclusions

Sources and further reading for this chapter

Part III: Just How Do I Do It?

Chapter Four It’s All in the Mind

Getting down to the nitty-gritty – the meta-model of language

Presuppositions

Nominalisations

Developing the “Merlin” in you – hypnotic language approaches

The case for obscurity

Storytelling and metaphoric language

Shaped daydreaming or state-inducing talk

Stories in quotations

Words that change the internal mindscape – other linguistic approaches

Sleight of mouth

Verbal aikido and fogging

Motivational talk

Reframing

The language of choice

NVC – nonviolent communication

Using counselling approaches

Solution-focused brief counselling

“Clean” language

Key conclusions

Sources and further reading for this chapter

Chapter Five The Scripts

Speech to calm the anxieties and raise self-esteem

Centring scripts

Addressing the specific anxieties

Using the meta-program patterns

Using the meta-model

Gestalt approaches

Using the Milton model and other “hypnotic” scripts and strategies

Example of a Milton vague communication

Embedded commands

An example of a guided visualisation

Sleight-of-mouth patterns

A miscellany of useful words

Part IV: What Can I Do With This Learning?

Chapter Six Putting It All Together

Language to improve behaviour – neuro-linguistics in action in your classroom

General rules of engagement

Negative and positive statements

In conclusion

Bibliography

Acknowledgements

Copyright

List of figures

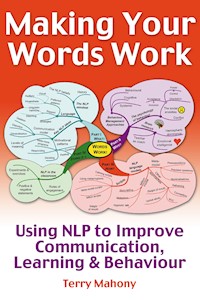

Mind map of the book cover

Figure (i): Reading this book

Figure 1.1: The NLP communication model

Figure 1.2: The conscious–unconscious mind connections

Figure 1.3: The neurological levels (after Dilts)

Figure 1.4: The ladder of inference

Figure 1.5: McCarthy’s 4-MAT

Figure 1.6: The towards/away-motivation meta-program

Figure 1.7: The body-mind connections

Figure 2.1: The NLP language models

Figure 2.2: The zone of proximal development (ZPD)

Figure 2.3: Mindscapes of learning

Figure 2.4: The mindscape-making process

Figure 2.5: Peter’s strategy

Figure 3.1: A model of teacher–pupil interaction

Figure 3.2: Flow

Figure 3.3: Patterns of conflict behaviour

Figure 3.4: Misbehaviour strategy and teacher interventions

Figure 3.5: A linear model of behaviour change

Figure 3.6: The diminishing of full potential

Figure 3.7: The motivational ladder

Figure 4.1: Sleight of mouth – strategies for breaking out of the box

Figure 4.2: Thinking in the box

List of tables

Table (i): The NLP language approaches

Table 2.1: Predicate words and phrases heard in teacher talk in behaviour management

Table 3.1: Classification of behaviour-management approaches

Table 3.2: The three basic social anxieties

Table 3.3: Positive intentions and entitlements

Table 3.4: The spectrum of teaching roles

Table 3.5: Anxiety-driven strategies for handling conflictTable 3.6: Conflict and language

Table 3.7: Questions at the different neurological levels

Table 3.8: The four Fs of behaviour and teacher-distorted responses to conflict

Table 4.1: Meta-model examples

Table 5.1: Motivating language for the “mental” meta-programs

Table 5.2: Precision questions – the meta-model in use

Table 5.3: Gestalt language shifts

Table 5.4: Milton model statements – the meta-model patterns in reverse

List of exercises

Exercise 1.1: Know your linguistic meta-program filters

Exercise 2.1: Psycho-geography!

Exercise 2.2: Being your own mediator – a perceptual-positions exercise

Exercise 2.3: What is your preferred vocabulary?

Exercise 3.1: Anxiety

Exercise 3.2: Personal emotional competence – a tracking exercise

Exercise 3.3: Which is your most likely approach to conflict?

Exercise 4.1: Using the meta-model

Exercise 4.2: Breaking out of the box

Acknowledgements

My thanks to the many teachers who have contributed to this book by testing these methods in their classrooms and to my colleagues, who have read, critiqued and suggested improvements in its format. Thanks to Brian Vince for one of his many poems. And to Marianne, without whom it would never have been finished.

Preface

“We have known for some time that learning (making sense of their experience) is at its best for most children when they are interacting socially and that language and communication is the key to successful learning. ‘Children solve practical tasks with the help of their speech as well as with their hands and eyes.’”

– L S Vygotsky, Thought and Language

Much research has taken place in the last few decades that shows the power of words in shaping people’s worlds However, as with all research, there is a time lag between the discovery of new ideas and relationships and their application in the classroom. A number of books have been written exploring the educational applications of neuro-linguistic programming (NLP) techniques in classrooms, mainly in the area of accelerated learning. However, NLP does have a wider application, because it is a model of human communication and behaviour that comprises three broad elements:

Gaining rapport and communicating with another person;Effective ways of gathering information about the mental world of another person; Strategies for promoting behavioural change.As such it is ideally suited for managing classroom behaviour, especially as it uses both conscious and unconscious ways of relating to and communicating with another person. In particular, it has developed ideas and techniques that will allow you to identify and describe patterns in the verbal and nonverbal behaviour of children. This book explores the NLP ideas relating language to behaviour. Language and communication are the basis of successful learning for children. My belief that the forms of language a teacher uses shape the behaviour and therefore the learning of the children in the classroom prompted this description of the ideas and teaching techniques advocated in this book. Its purpose is to get you a classroom where behaviour supports your children’s learning.

Learning in classrooms is mediated by the teacher and this mediation is language-based. This book is about ensuring that the language you use increases your pupils’ capacity to learn. Carefully chosen language can actively create the mental images and neurological pathways in the brain of the child to produce the desired learning. I have taken the findings of NLP that can be applied to behaviour and converted them into practical ways of talking and behaving in the classroom.

All experienced teachers have watched or listened to an exchange between a student teacher and a pupil and recognised that turning point in the conversation when conflict becomes inevitable, triggered by the student’s inappropriate verbal response to the pupil. I want all teachers to have at their command the widest repertoire of linguistic tools so that they can alter the direction of any exchange with a pupil to move it away from conflict and towards the restoration of a learning climate in the classroom.

In 1994, a UK government circular stated that behavioural problems with children were “often engendered or worsened by the environment, including schools’ or teachers’ responses”. Stop for a moment and remember an exchange with a pupil that didn’t go the way you wanted it to. Was your response to the situation as good as it could have been? What did you say that worsened the situation? Now think of being able to communicate with just the right language to get the positive outcome you intended. This is what the NLP language patterns contained in this book can help you to do. The book will show you how to use these patterns in such a way that you will be able to improve the behaviours of the pupils you teach. They are easily learned ways of talking that you can develop into an unconscious competence in your classroom. With your new competence will come reduced levels of tension and noticeable shifts in the climate of the classroom. Just as different colours have been shown to affect mood, so specific language patterns, vocabulary and ways of talking can shift the emotional state of the listener.

Just think of your own internal dialogue in different situations. What do you say to yourself to wind yourself up from a feeling of mild irritation, through annoyance, to full-blown anger? Equally, just recall what you say in your head to calm yourself down or move into a state of feeling pleased with yourself. We each have our own internal dialogues which affect our mood or emotional state. Some of these have been installed in our behaviour for such a long time that we have probably forgotten the experience that first prompted them. More importantly, they act like preprogrammed tapes that begin to run in our mind’s ear when something triggers them. These messages in turn generate a behavioural response that can sometimes be dysfunctional when we are dealing with a child’s misbehaviour. Recognising your own self-talk tapes from the past and learning to create more appropriate ones is a key emotional-skill development for all teachers.

This book is structured with the reader, and what we know about personal learning, in mind. It falls into four sections appropriate to your learning preference:

Part I covers the bottom right-hand side of the diagram in Figure (i): the what of the book, its main ideas and the background research that have led to the development of these techniques. Chapter One contains the ideas and concepts underpinning neuro-linguistic programming. It gives a brief history and background to the development of NLP as well as a description of its main tenets and how you can implement them into the classroom. This will give you an overview of the field and allow you to decide which ideas can help you most in your classroom. Although this book focuses on the use of the linguistic devices of NLP, the Bibliography lists those authors who have described how these and other powerful NLP techniques can help you enhance children’s learning.

Chapter Two contains recent thinking in brain research applied in the classroom. It is a short wander through some of the key findings of the research of the last decade into the brain’s structure and functioning, as well as the ideas on the use of specific language in modifying behaviour.

Part II (the top right-hand quadrant) explores why you will want to read and learn about these ideas. It surveys some of the current behavioural problems and practices in school. It explores what implications these may have for children’s learning and behaviour. Much of this work has yet to be really tried and tested in the classroom. What findings do you think you can use and change your teaching approach? You can be the experimenter and see the effect of some of the ideas in improving children’s learning.

Figure (i): Reading this book

Part III covers the bottom left-hand side of the diagram, the how of the different techniques and how they are used to gain different goals with the same outcome – better behaviour. This section contains a survey of the words, phrases and scripts of the different NLP approaches to use in the classroom, together with ways of strengthening some of the more common current strategies. Chapter Five has practical examples and conversational “scripts” of the patterns in use. Simply choose a script or a technique and ask yourself if you can remember an occasion when it could have improved the outcome of a confrontation with a pupil.

Part IV concerns what you can do with them in different situations. I suggest you choose one or two specific examples from these, linked to familiar scenarios or situations that are likely to occur in your classroom. You can use them when the appropriate occasion arises. Then note the effect they have and consider how the outcome is different from what it might have been like if you had used your usual way of responding. As you become familiar with them, so you can learn others and gradually extend your repertoire of responses.

These ideas can have meaning and worth to you only if you experiment with them in the classroom. An old proverb says that knowledge is only a rumour until it gets into your muscles. In other words, these approaches and scripts have to come alive. Only then can you discover and value the ideas and practices described in this book. As teachers, we tend to experiment most with different strategies in the early part of our careers and gradually sort those that have been tested and worked from those that failed. Many of us rely on these tried and tested ways of teaching and then sometimes, unnecessarily, limit our teaching repertoire to them. Under pressure they become our classroom survival strategies, because no one likes to fail too often. Yet “failure” is part and parcel of the normal learning process. Scientists work with the belief that there is no such thing as a failed experiment. Edison always claimed that he did not have a thousand failed attempts to make a light bulb; he just learned a thousand ways how not to make one! Each experiment was a source of feedback on his path to being successful. If, as professionals we shun “failure” by taking no risks, then we run the real risk of forgetting how to learn. In a rapidly changing environment, learning how to learn is the one skill we need most. So communicate well – or disappear in a struggle to maintain a learning environment. In today’s classrooms, it is vital to be a good communicator.

Getting the most benefit out of this book

Many teachers ignore potentially useful research findings because they do not value them. They do not value them because they have not experienced them for themselves. It does not matter how rational the research, how erudite the analysis and how persuasive rationally the conclusions if you as a teacher have no emotional attachment to them, for you will not convert them into practice. Think of smoking: just reading all the research and knowing the likely implications for future ill health doesn’t necessarily change the individual smoker’s behaviour. Head, heart and hand have to work together to bring about a new behaviour. So, to get the most out of this book, you will need to use the ideas in your classroom. If nothing is said or done, it remains a book. You can begin by reading the sections in any order you wish. Read the one that appeals to you most. If you like to see the big picture or feel the need to grasp the whole thing, before you can feel comfortable with practising something new, then read the book as it is written. If you have a stronger, predominantly “suck it and see” approach to your own learning, then begin with Parts II and III. Become familiar with one or two of the actual patterns and use them in the classroom as appropriate situations arise. Note the outcomes and which of these patterns work for you. Continue to extend your knowledge and use of them – they become easier with practice – until one day you will find yourself using all of them smoothly and effortlessly as and when they are needed. Then, if you are curious about just why they have the effects they do, return and read Part I. If you already have some knowledge about NLP you can leap straight to Part IV and choose some of the experiments with the techniques suggested there.

Introduction

“Words are the main currency of our trade.”

– Dhority, The ACT Approach: the use of suggestion forintegrative learning

What makes a good teacher? Why are some teachers really good behaviour managers? When you stop and think about skilful behaviour management in the classroom, what comes to mind? As in all ages and even in this increasingly electronic age, Dhority’s words are very true for teachers: words are our work! All good teachers are unconsciously skilful in their use of language to engender learning in their students. What changed in the last few decades of the last millennium was the rapid expansion in the scientific knowledge of the brain’s functioning and the importance of language in the development of the maturing brain.

The study of how language and action affect the central nervous system is known as neuro-linguistic programming (NLP). Prior to its scientific underpinnings, it was once defined as an attitude ofcuriosity that leaves behind it a trail of techniques. Different researchers followed their curiosity in this field and discovered a range of patterns from which they developed techniques applicable to education. These techniques are finding their way into the classroom and this book takes what NLP tells us about language and communication and applies it to the daily interaction between teachers and pupils.

Many teachers have already found that, by using the suggestions to change their language and their vocabulary, they get better class control through improved behaviour from their pupils. It’s not just about talking; it is about developing new patterns of conversation (ways of talking) that open up new ways of pupils’ thinking. Words trigger internal representations and start processes in our mind. The “right” words are needed to produce the representations we wish to stimulate. We now know that different languages result in differently organised brains.

As the form of the language is different, so the neural paths that are formed while the young child is learning develop differently according to the language being acquired. Learning English, for example, with its alphabet of only 26 abstract symbols arranged linearly to form hundreds of thousands of words, will produce a differently wired brain from that of a Chinese child acquiring its native language constructed of the combination of thousands of individual pictograms. “Language development changes the landscape of the brain radically” (Carter, 1998). Pacific island peoples with no written language develop a wider range of kinaesthetic or nonverbal means of communication. Recent research (Jensen, 1994) shows that even after the language has developed, words can still alter the physical structure of the brain. Brain scans using positron emission tomography (PET) have demonstrated that carefully chosen words can activate the same areas of the brain, and have the same therapeutic effects, as a proprietary drug such as Prozac!

If we extrapolate this research it could support the underpinning premise of this book: altering what you say and the way that you say it can stimulate changes in the behaviour of the listener. As a teacher and a mediator, I believe in the persuasive power of language. This research supports that belief.

Professional mediators recognise three sets of skills in conflict management:

Identifying patterns in and behind conflict – patterns in the anxieties that people exhibit; patterns in the individual approaches to conflict as a protagonist. Establishing a climate of nondefensiveness in both parties, which can depend on subskills such as gaining rapport easily, the use of assertive strategies at the appropriate time, the ability to change or modify belief systems and the different ways people see the same facts. Communicating to ensure that conflict prevention and resolution by conversationally redefining positions and issues dampens down the emerging conflict.This book focuses on the last skill: the development of sophisticated language skills and the linguistic devices and specific speech patterns that ensure improved communication. Although its main emphasis is on the language patterns of NLP, it draws on other aspects to aid the first two skill areas. There are three broad fields of language in NLP. They are used deliberately to achieve different outcomes. This book will provide you with a description of the ideas contained in each field, where they can be applied in the classroom and examples of the different speech patterns in all three. Skill in the choice of which mode of language to use and in the specific speech patterns within each field will help create the classroom climate that is conducive to purposeful learning.

Good teachers intuitively use all three ways of communicating when teaching. The aim of this book is to increase your awareness of the greater potential of these approaches when you understand how they can be used deliberately to shape the behaviour of your students. All teachers want to make a difference. Each one of us in education wants to influence for the better the lives of our students. With a greater knowledge of the NLP language patterns, teachers are achieving the positive differences they want, because they understand, first, how the language used shapes the internal world of the listener, and, second, how that drives their outer world, the one of behaviour. And so I wonder how soon it will be before you begin to try out these ideas in a way that will develop the learning behaviour in your classroom.

Part I

What Am I Going to Learn

Chapter One

General Elements of NLP

Having originated some 25 years ago and having developed rapidly over that period, NLP has had an increasing influence on the science and practice of communication. The “technology” of NLP – its conceptual models, its practical methods and techniques – can provide teachers with a wide-ranging understanding of how children think and behave, and therefore how we can help them change. It links what we know about the neurology of our body, mind and senses with our spoken (and unspoken) communication patterns, and helps us to better understand our behaviours. It is based on the knowledge that language does much to determine the development of the neural pathways in our brains and therefore, over time, programs much of our behaviour. This idea of habitual reinforcement of the brain’s physiology through language to strengthen some neural connections in preference to others is evidenced by the assertion that, of the 80,000 or so thoughts you may have today, probably at least 60,000 are the same as yesterday’s!

The set of processes which have been developed in NLP help you to:

Develop relational and influencing skills through improved rapport; Use easily identifiable language patterns to communicate more powerfully; Recognise the motivational patterns of individual children and therefore respond more effectively to their behaviour.Up to now, in education, NLP has impacted mainly in the field of accelerated learning and not in behaviour management. However, experienced teachers already use a range of the wider basic ideas of NLP in an intuitive way, having developed their own personal classroom strategies through trial and error in the hurly-burly of dealing with the year-on-year task of teaching the children in their own classrooms. Since the 1980s, the ideas and techniques of NLP in improving communication have been applied in projects in teaching and learning (e.g., Jacobsen 1983; Grinder, 1991; Blackerby, 1996). They have been found to be very practical ways of improving children’s motivation and therefore their behaviour and their learning. The more you can use the techniques to gain the understanding of the linkage between words and behaviour, to explore your own experience in the classroom and what you do with it, the more you can bring about behavioural change in your students. And your teaching will become more effective.

Remember, all the ideas presented here are models. Like all models they are representative of reality, not reality itself. The worth of any model lies in its usefulness in helping us address current problems or issues. Newton’s model of gravity is not our current understanding of the mathematics of the universe; it was replaced by Einstein’s model because his equations solved problems that Newton’s couldn’t. However, that does not detract from the huge leaps forward in our understanding of the world that flowed from Newton’s model. It helped solve three hundred years’ worth of problems. Nor does it alter the fact that it still has application, including the calculations behind first putting a man on the moon’s surface! So it is with the NLP models. There is no claim that they are what really happen inside the mind. As with Newton’s gravity theory, though, applying the NLP ideas has resulted in remarkable achievements over the last thirty years in the fields of health, therapy and, more recently, education. Now is the time to apply them specifically to behaviour management. You can judge their usefulness.

The NLP mindset: guiding principles for excellent behaviour managers

The current practice of neuro-linguistic programming is based on a set of principles or key beliefs. Success in managing children’s behaviour depends on your own attitudes, beliefs and values. They help you to clarify your own values and to notice their effect on your relationships with your students. This set of key beliefs has been selected from the NLP principles most relevant to behaviour management in the classroom. You may not believe them all, yet; for some, just act as if you did believe them. Don’t think that you will always find this easy, but you can notice the changes that occur when you can act as if you believe them all. The practices recommended in this book are based on these principles.

1. Behaviour is the best bit of information about a person Only a fraction of any spoken communication is carried by the actual words. Your tone and other qualities of your voice will carry a message four or five times stronger. All behaviour serves as a communication. Your task is to develop a behavioural “language” that will work in managing pupils. Applying this principle means observing closely what they do, without interpretation, without “mind-reading” – you don’t need to know the why of what they are doing. In NLP answering the question “How do they do what they do?” is considered far more useful in getting to a win/win state than in seeking a reason for why pupils do what they do.

2. People are not their behaviour Be clear of the conceptual level of your thoughts and actions. As a teacher you already take care to describe the child’s behaviours as not acceptable, not the child’s identity as a person. This relates to Robert Dilts’s neurological levels (see “The levels of meaning”).

3. Every behaviour has a positive intention behind it It may not always seem that way to you, but somewhere, at some level, everyone behaves out of a good intention. It may be hard to see it from your viewpoint. You will have to see it from theirs, to get a feel for what it means to them. But, whatever it seems like to you, their behaviour is intended to be useful to them or to be protective of their wellbeing. William Glasser (1998) in describing his “choice theory” makes the same point slightly differently: “We always choose to do what is most satisfying to us at the time.” An important skill in behaviour management is the ability to interpret the underlying message being conveyed by the behaviour and not to focus solely on the behaviour itself. It is good to ask oneself, “What is this behaviour a symptom of?” or “What is the need underlying this behaviour that the student thinks will be met by acting this way?”

4. Emotions are facts Emotions have to be taken into account in your everyday life. They are real, even if self-generated, and will affect your behaviour. Your emotional feelings are the result of an interaction between what you tell yourself about your experience and your basic gut feelings. So you bring them into existence and, once present, they have to be incorporated into the equation of how you interact with children.

5. There are no difficult children, just difficult relationships andinflexible teachers “Difficult” children are those children you give up on when you cease to be flexible in your responses to them and communication is broken off. Resistance is not so much an attribute of them but more a measure of your inflexibility of response. This can be hard to accept, let alone believe, but experiment with behaving as if you did believe it and notice the differences in the responses you get. This book is designed to increase your flexibility by enlarging your repertoire of techniques.

6. The meaning of my communication is the response I get Many communicators are too busy talking to notice the effect of their message. The surest way to know what you have “said” to another person is to listen to the response you get back. You may know what you meant but, if the response does not confirm that your particular message was received, then you know you didn’t convey it – you sent a “missage”. They missed your point. You will have to rephrase it until it becomes a message – something they can understand. When a child asks an off-the-wall question, ask yourself, “How is it possible that this child can ask such a question at this moment?” The answer to that question lies in the question asked. What have you not done or said that could trigger that particular question in the child’s mind?

7. All children have the resources they need to meet the challenges of everyday living Children are often unable to find within themselves new ways of behaving, because they are in an emotionally unresourceful state. Anxiety distorts behaviour and thinking closes down with high levels of negative emotion. With it goes the ability to find solutions within oneself. Relieving anxiety or reducing its level is the first step in helping a child look for alternative behaviours. This belief in the individual’s own innate resourcefulness is an underpinning principle of “brief counselling” approaches.

8. We all have our own internal map of reality A map is just a symbolic representation, a model, not reality. We create our world by the words we use to describe what our senses tell us. We select from our senses what it is that interests us, and our own past experiences and learning help us decide what we will pay attention to in the world around us, what we will focus on. Two people can look at the same car accident and describe it in two very different ways. Two people can look at the same picture and see two different images. The word pictures we have created in our own mind to describe the picture are just that – in our mind. They are not the original event that prompted them. By the time children have come to you they are likely to have answered three questions for themselves: “What sort of person am I?”; “What sort of world am I in?”; “What happens in a world like mine to someone like me?” The answers to these questions may seem distorted or illogical, but are very real to them; and they will have helped design their internal mental map – their worldview.

9. Children respond to their map of the world – not yours A consequence of the above is that all children do things for their reasons, not yours! It makes sense in their unique maps of the world. And that’s the world you are going to have to enter to make a genuine difference in their behaviour! You may demand compliance in learning, but, if you do, you are unlikely to get commitment to it!

Some of the key elements of NLP

1. The simple NLP communication model

In A Brief History of Everything, Ken Wilber wrote:

The brain physiologist can know every single thing about my brain – he can hook me up to an EEG machine, he can use PET scans, he can use radioactive tracers, he can map the physiology, determine levels of neurotransmitters – he can know what every atom of my brain is doing, and he still won’t know a single thought in my mind … And if he wants to find out what is going on in my mind, there is only one way that he can find out: he must talk to me.

Wilber makes the point that the scientist can know everything about the concrete “exterior” of the mind in terms of the brain and the nervous system, but the “interior” of another’s mind can be revealed only through dialogue with that person. It is a black box to us – we see a container and we see the behaviours it produces, but have little idea what is inside the container that results in that observable output. Scientists are well used to dealing with this problem and circumvent it by constructing a model. Indeed, science is a discipline that spends its time devising better and better models of the observable realities that interest it. NLP has a particularly elegant model of human communication (Figure 1.1). The human mind has to be very selective in what it pays attention to, since it receives up to two million pieces of data every second! It has to reduce the complexity of all this information if it is to make sense of what it is experiencing at any one moment. The brain’s primary task is to keep the body healthy physically (and psychologically). Perceiving the environment demands selection – choosing just what sensory input to pay attention to – and its prioritisation. We therefore disregard what we consider unimportant at that time.

Figure 1.1: The NLP communication model

What we pay attention to depends largely upon our beliefs and values. It is these that help us select the data that fit our mindscape and transfers these as chosen memories for our conscious mind, so that we can easily recall them later on. In the model, these selection and perception processes are represented by the three filters of deletion, distortion and generalisation. (And remember, this is only a model – it is not reality! The idea of filters is only a convenient way of thinking about the internal processes. What they represent is the process by which we choose from all the data surrounding us that which we consider “information”. That is, data that mean something to us and will inform our future behaviour and beliefs.)

Apart from the need to cut down the sheer volume of information bombarding us, the main psychological driver for the deletion, distortion and generalisation processes is to shape the incoming information to fit our internally held view of ourselves and the world we inhabit. In this way, we maintain our beliefs, our values and our own self-image.

Chosen data or pieces of information are often associated with an emotion which makes their recall easier. The rest of the unwanted (unwanted, that is, for right now) two million bits of data may be stored below our threshold of conscious awareness. However, your unconscious mind notes them and, driven by your deep beliefs and values, may prompt you to behave in a way that does not always seem logical to your consciously aware, thinking mind. John Grinder (1991) puts this slightly differently by asserting that the literal part of the message is understood at one level, while its intent is absorbed at another. “We know more than we can tell” (the philosopher Michael Polanyi).