5,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

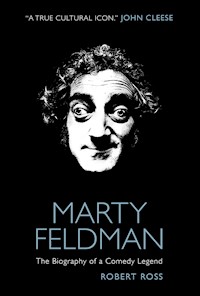

Mike Myers thinks he was "a genius", while John Cleese regards him as "a true cultural icon". He was an architect of British comedy, paving the way for Monty Python, and then became a major Hollywood star, forever remembered as Igor in Mel Brooks' Young Frankenstein. A writer, director, performer and true pioneer of his art, he died aged only 48. His name was Marty Feldman, and here, at last, is the first ever biography. Acclaimed author Robert Ross has interviewed Marty's friends and family, including his sister Pamela, Tim Brooke-Taylor, Michael Palin and Terry Jones, and also draws from extensive, previously unpublished and often hilarious interviews with Marty himself, taped in preparation for the autobiography he never wrote. No one before or since has had a career quite like Marty's. Beginning in the dying days of variety theatre, he went from the behind-the-scenes scriptwriting triumphs of Round the Horne and The Frost Report to onscreen stardom in At Last the 1948 Show and his own hit TV series, Marty. That led to transatlantic success, his work with Mel Brooks including his iconic performance of Igor in Young Frankenstein, and a five-picture deal to write and direct his own movies. From his youth as a tramp on the streets of London, to the height of his fame in America - where he encountered everyone from Orson Welles to Kermit the Frog, before his Hollywood dream became a nightmare - this is the fascinating story of a key figure in the history of comedy, fully told for the first time.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Ähnliche

“Every Saturday evening I would watch The Marty Feldman Comedy Machine. Igor in Young Frankenstein was written for Marty. I was thinking of him all the time. No-one else could have played that part.”

GENE WILDER

“When you’re a comedy writer you pray for Marty Feldman. He not only met your material, he lifted it. He gave it that magic touch.”

MEL BROOKS

“Marty had one of the sharpest comedy brains in anybody I have ever met. He was a lovely man as well. Almost unique.”

MICHAEL PALIN

“Marty was the perfect comedy script editor. The veteran centre half who steered the new defence.”

SIR DAVID FROST

“He had a wonderful comedy presence. He is a true cultural icon.”

JOHN CLEESE

“I love British comedy. I learnt from it. Marty Feldman was a genius. Crossed eyes are funny!”

MIKE MYERS

MARTY FELDMAN: THE BIOGRAPHY OF A COMEDY LEGEND

9780857686022

Published by

Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd.

144 Southwark St.

London

SE1 0UP

First edition: September, 2011

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Marty Feldman: The Biography of a Comedy Legend © 2011 Robert Ross. All rights reserved.

Did you enjoy this book? We love to hear from our readers. Please e-mail us at: [email protected] or write to Reader Feedback at the above address. To receive advance information, news, competitions, and exclusive offers online, please sign up for the Titan newsletter on our website: www.titanbooks.com

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

Printed and bound in the UK by CPI William Clowes, Beccles, NR34 7TL.

MARTY FELDMAN

The Biography of a Comedy Legend

ROBERT ROSS

TITAN BOOKS

“I have a Holy Trinity, which is Buster Keaton the Father, Stan Laurel the Son and Harpo Marx the Holy Ghost.”

For Lauretta and Barry, Marty’s other halves.

CONTENTS

Acknowledgements

Prologue:

“It doesn’t bother me how they describe me. I’m me and that’s it.”

Chapter One:

“Money can’t buy poverty.”

Chapter Two:

“I won the award for being the best loser.”

Chapter Three:

“I feel about Keaton the way an organist thinks of Bach.”

Chapter Four:

“I don’t think of myself as a comedian or a clown.”

Chapter Five:

“I don’t enjoy anything while I’m doing it. I enjoy having done things, though.”

Chapter Six:

“Other artists can put over my material better than I can.”

Chapter Seven:

“... stuffing live nightingales down my throat until their beaks stick out of my ankles.”

Chapter Eight:

“Comedy, like sodomy, is an unnatural act.”

Chapter Nine:

“I can’t tell jokes. I’m the character in the joke.”

Chapter Ten:

“Once you’ve realised you’ve got the kind of face people laugh at, rather than swoon over, you concentrate on making people laugh.”

Chapter Eleven:

“One of the nicest things about success is that I’ve been able to get tickets very easily to see Chelsea play.”

Chapter Twelve:

“I let my energy express itself in physical terms that often leads to broken bones and injuries.”

Chapter Thirteen:

“If it’s overnight success it’s been a very long night.”

Chapter Fourteen:

“I don’t want to be a director, I want to direct. There’s a difference.”

Chapter Fifteen:

“I won’t eat anything that has intelligent life, but I’d gladly eat a network executive or a politician.”

Chapter Sixteen:

“I’m too old to die young, too old to grow up.”

Epilogue:

“I do not disbelieve in anything. I start from the premise that everything is true until proved false. Everything is possible.”

Marty’s Credits

Notes

Index

Acknowledgements

“Just before they made me, they broke the mould.”

A salute to the inspirational comedy of Marty Feldman has been a pet project of mine for several years, so firstly many thanks to Adam Newell at Titan Books for sharing my passion for the subject. I am eternally grateful to the late Barry Took. After my first book was published in 1996 I got to know Barry well, meeting up at countless screenings, signings, Broadcasting House assignments and memorial services. These always ended with a pint or two in the nearest public house and, unless otherwise stated, Barry’s memories come from those impromptu chats. I am also greatly indebted to Marty’s friends, and fellow performers and writers Dick Clement OBE, Bernard Cribbins OBE, Barry Cryer OBE, Vera Day, Harry Fowler MBE, Ray Galton OBE, Derek Griffiths, Bill Harman, Terry Jones, Denis King, Ian La Frenais OBE, Warren Mitchell, Bill Oddie OBE, Michael Palin CBE, Alan Simpson OBE, Alan Spencer, Graham Stark, Sheila Steafel, Brian Trenchard-Smith, David Weddle, Ronnie Wolfe, Rose Wolfe and Nicholas Young for insightful memories and encouraging words. A very special thank you goes to Tim Brooke-Taylor OBE, who not only shared his many Marty stories but also made the initial connection with Tony Hobbs. Tony’s preservation of the interview tapes conducted by his late father, Jack Hobbs, has proved invaluable. A writer, editor and jazz pianist, Jack Hobbs and Marty were kindred spirits of the Soho jazz spots and drinking clubs. As a result “The Marty Tapes” are both relaxed and candid; as Marty says, “It’s all very rambly. Just things that happened.” If no source is given, Marty’s comments come from these. I am hugely indebted to Marty’s sister Pamela Franklin and his niece Suzannah Galland who provided me with wonderful memories and insights. Telephone conversations with them both have been hilarious, informative and heart-warming. They have also sifted through the family archive and provided some truly unique photographs for the book. Their support has been totally invaluable. I also thank Jeff Walden at the BBC Written Archives and Sarah Currant at the British Film Institute Library who was particularly enthused during many googlyeyed sessions. I gratefully acknowledge the kind permission of General Media Communications, Inc., a subsidiary of FriendFinder Networks, for the quotations from ‘The Penthouse interview – Marty Feldman’ by Richard Kleiner, published in the October, 1980 US Edition of Penthouse magazine. Many thanks to Larry Sutter for arranging this. Thanks to Sharon Gosling for her Battlestar Galactica connections. I thank those stalwart people Alan Coles, Henry Holland, Melanie Clark, Paul Cole, Dick Fiddy, Andrew Pixley and Bob Golding for being supportive. Love and thanks to Abby (Normal) Naylor. And lastly to my Mum, Eileen, who is invariably the first person to read anything I write. Thank you!

Prologue

“Good Lord Boyet, my beauty, though but mean, Needs not the painted flourish of your praise: Beauty is bought by judgement of the eye, Not utter’d by base sale of chapmen’s tongues” William Shakespeare

“It doesn’t bother me how they describe me. I’m me and that’s it. I have to admit my face helps me in my work as a comedian. It used to worry me a bit when I was seventeen or eighteen, when I was trying to pull the birds. But now I don’t worry any more.”

Today if you mention the name Marty Feldman to even the most ardent of comedy fans, the chances are you will get one of two responses. Either an affectionate chuckle at those lop-sided eyes of his as he gallantly crusades through psychedelic sixties countryside, usually with a golf club firmly gripped in his hand; or, more likely, an affectionate chuckle at those lop-sided eyes of his as he channels old-school vaudeville within a vintage Universal horror setting, with a cry of “What hump?”, or one of a dozen or so other deliciously quotable lines from Mel Brooks’ Young Frankenstein.

For Young Frankenstein remains the most celebrated and accessible example of Marty’s work: an international, block-busting comedy success that made him a Hollywood favourite at the age of forty.

“Marty was saddled with this title of clown,” says his friend Bill Oddie. “It was almost as if God had given him the make up and the costume: ‘We’ll have these googly eyes and the Harpo Marx hair and the slightly odd accent – a bit of cockney, a bit of Jewish. The slightly crooked nose. And you were made to play hunchbacks and other comedy weirdoes. There you go, son.’ It was like this was the way he was delivered to the world. Like a clown in kit form.”1

Marty was painfully conscious that his features shaped his life: “I have always been idiosyncratic and something of an aberration,” he said. “I’ve always been treated as a freak anyway, and in a sense I am. I’ve always felt like an alien who never belonged anywhere: just a temporary member of the human race.”2

But for Marty, despite the international success of Young Frankenstein, life didn’t begin at forty. Although he had reached fulfilment as a film star and his future in Hollywood looked guaranteed, never again was he as relaxed, creative, popular or just plain likeable on screen. Bitter clashes with studio executives and an endearing refusal to compromise his integrity saw his most personal projects scuppered by corporate politics. Almost as soon as he tasted fame in America he began missing the “hungry” years in England. But not in that glorious, all-conquering winter of 1974.

Marty had made it. This was the pinnacle he had worked so hard to achieve. “I’m driven,” he said. “The impulsion is from behind me. I go where that takes me and it takes me to some strange places!” As the California sunshine shone and the palm trees swayed, an endless line of media interviewers clamoured for his thoughts on the film industry and life in general; not that Hollywood was that interested in life in general. Still, throughout it all, Marty doggedly retained his Englishness. Talking to the Daily Express Hollywood reporter, Ivor Davis, Marty sported his prized Chelsea football shirt – once worn by Charlie Cooke circa 19703 – and his favourite pair of blue jeans. He had upped sticks from Hampstead to Hollywood simply to be where the film industry was but, typically, he didn’t feel at home in either place. He was “a martian – like most comics.”4 Even his dream destination of Hollywood was an empty sham. His home in the Beverly Hills was rented and rumours of a nod from the Academy for his iconic performance as Igor came to nought. He wasn’t even nominated.5

Still, he was in Hollywood and that wasn’t all bad. It was a long way from the thankless slog around British variety theatres as part of Morris, Marty and Mitch. In 1974 he was more likely to be spotted at the Hollywood Bowl than the Chiswick Empire. His friends and colleagues were the likes of Dean Martin, Orson Welles and Groucho Marx rather than bottom of the bill variety turns.

But Marty retained his affection for his early days. That far-off time when a combined passion for jazz and silent comedy propelled him through a myriad of dead-end jobs and half-realised ambitions. He was most content in his favourite London haunt, Ronnie Scott’s jazz club, or as Tim Brooke-Taylor says: “Marty would be at his happiest in a Paris café, smoking and talking about the latest French film or obscure jazz artist.”6

As he sipped fruity-flavoured alcohol and mapped out his first big solo Hollywood project, Marty could look back on a twenty-year long stint of writing comedy. Throughout the 1950s he had written solid situation comedy and radio variety for the big names of the day. He had brought fresh blood to ITV’s flagship show The Army Game and put words into the wooden mouth of Peter Brough’s badly behaved ventriloquist dummy Archie Andrews.

Family-geared entertainment for the masses, but with Marty’s jet-black comic imagination in the mix, a deceptively mild show could conceal sharp barbs of satire and surrealism. This taste for, in effect, bucking the trend of British comedy found its longest-lasting and most potent home in BBC Radio’s Round the Horne. One of the four cornerstones of radio humour, the show was a Trojan horse of smut, satire and silliness. The English Sunday lunchtime was never quite the same again.

But Marty was nobody’s fool. He knew that success in England meant very little to the majority of his American audience. Indeed, success as a scriptwriter didn’t mean all that much to audiences in England either. Rather than being famous for over a decade, he was simply known; and then only by a relatively select few. He was known as the most inventive, prolific and speediest scriptwriter in the business. His sharp mind and world-weariness captured within those scripts of his. An off -kilter squint at life wrapped in cosy familiarity.

In America, the lengthy list of writers on a television show would whiz past your eyes so fast no one was known except the star of the show. Woody Allen and Neil Simon may have been slaving away behind the scenes but Sid Caesar was the national treasure. It was only when Marty went out on a limb and in front of the cameras that audiences sat up and took notice. Only when colour was added to the mix would American stations begin to bring Marty’s outlandish blend of slapstick and surrealism to an even wider audience. Every decade or so America would pick up an English performer and embrace him. They would almost always become a sideshow freak. The English comic tempted over from his homeland to sit in captivity in Hollywood and entertain studio bosses with their funny accent and outmoded good manners. In effect it was America poking him with a stick and making him dance. However, Marty was only going to dance to his own tune.

It was an approach to comedy that Marty had firmly established during a fairly short period at the BBC. Pied Piper-like, he had a choice collection of writers and stooges who trailed after him wherever he wanted them to go. With his affable charm, softly spoken determination and keen perfectionism he found his niche on British television. Here was a performer unique in every sense of the word. His face was instantly recognisable, his comedy was deeply rooted in the past while continually taking huge strides into the future, and he was a star personality and performer who retained his dignity and humility.

In the late 1960s it was the coolest thing in the world to be English. Marty was at the epicentre of fashion, art, music and politics. He was a satirical hippie with mad hair, mad eyes and a heart full of justice for his fellow man. He was a guru for the comedy children of the revolution.

Michael Palin recalls “being in awe of Marty. He seemed so wise and assured at what he was doing.”7 Marty was perfectly suited to the surreal here and now of London in the late 1960s. He could wear a Flower Power T-shirt or a floral tie and make it look as “in” and “groovy” as John Lennon could. At Last the 1948 Show, the pioneering TV sketch series that made his name, may have been the immediate jump-lead to Monty Python’s Flying Circus and The Goodies but it was Marty and Marty alone who was propelled to almost instant solo stardom.

His name was big enough to put into the title of a television hit. Indeed, his finest work with the BBC was enjoyed under the simple, ego-pleasing title of Marty. Skilfully and lovingly combining the visual dexterity of Buster Keaton with the insane babble of Spike Milligan, Marty became a national figure of some clout and importance. More than just a comedian, he was a symbol for the swinging sixties movement of expression and self-censorship. As much a part of the in-crowd as Keith Richards, David Hockney and Terence Stamp, Marty would wear the latest fashion, support the latest campaign and comment on the latest world events.

He gave evidence for the defence at the Oz magazine decency trial at the Old Bailey and even recorded his own hit album of comedy songs. It was hardly Abbey Road, but still! Marty was the hip comedian. One of the beautiful people.

He could even charm the hard-bitten press. “What really amazed me about Marty,” wrote Lynn Barber of Petticoat, “was how soft-centred he is. His ‘malicious dwarf’ image on telly makes him seem hard and unsentimental, but when he talks he reveals his inner warmth. Unlike some showbiz people who utter a lot of heart-warming gush on stage, but would really boot their grandmother downstairs at the drop of a five pound contract – Marty’s sincerity is the genuine article.”

In some ways it must have seemed a lifetime away as Marty sat discussing his Igor character in Young Frankenstein. The classic television he had produced during the late 1960s and early 1970s was still vibrant and fresh in the States. Indeed, he would often recreate vintage material for American television variety spots. But in England he was already being thought of as yesterday’s man. The British audiences loved success, of course, but weren’t that keen on huge, American-sized success. There was always that danger that he would make a name for himself in Hollywood and never come back. As Marty’s own big film projects later crashed and burned and his presence on English television came to a grinding halt, the major insecurities started to emerge. For a performer who lived on his nerves, this was disastrous for Marty. He was the personification of the neurotic, tortured artist. “Comedy performing, or for me anyway, is a kind of neurosis which I exploit,” he said. “You plagiarise your inadequacies, your hang ups, and you make comic capital out of them.”8

But success on British television had just been a stepping-stone to success in American films. This wasn’t an arrogant attitude on Marty’s part, it was simply what he wanted. Or, as regular writing partner Barry Took noted, “what he thought he wanted. It was Marty’s dream to be making his own starring vehicles in Hollywood. He thought it would be just like the Golden Age of his heroes like Buster Keaton, Harold Lloyd and Laurel and Hardy. But of course it wasn’t. Hollywood in the 1970s was far, far different from what it had been fifty years earlier. It had always been a business but when Marty was making his films the business aspect was all-consuming. Keaton worked bloody hard but he had fun on set. One got the impression that Marty’s Hollywood experience was a pretty depressing one.”

Throughout the wild eighteen months that saw him burn brightest in Britain, Marty had become the most talked about and influential comedian in the country. His family life was his rock and his artistic passion was comedy. As long as there was room for jazz and cigarettes as well he was a very contented man indeed. His ego, though bloated by success, was never completely inflated.

In America, a few remnants of colour television insanity from Hollywood and a much-loved and influential turn for Mel Brooks wasn’t enough to sustain him. His subsequent collaborations with Gene Wilder and Mel Brooks would never equal the razor-sharp, freewheeling, unbridled joy of Young Frankenstein. His own writing and directing projects would turn into a living hell.

But that winter of 1974 must have been wonderful. An international star in a major box-office hit, Marty was fit, funny and forty. If the sun could have slowly sunk in the west and the end credits had rolled there and then, it would have been the perfect Hollywood ending. But, alas, that doesn’t happen: particularly not in Hollywood.

Chapter One

“Money can’t buy poverty.”

Ever since Marty Feldman’s face became public property in the swinging sixties, a thousand and one journalists have started interviews and appraisals with a pondering on that strange, pop-eyed child from London’s East Ham. Even when Marty was casting his directorial debut, The Last Remake of Beau Geste, and required a junior version of himself, he embraced the myth and tracked down a pop-eyed youth.1

In actual fact, when Marty first appeared, pink and soft and kicking and screaming, on 8th July 1934 he was a perfectly ordinary baby; angelic almost. He would pull interviewers’ legs and convince them that he was adorable. “As a child, I was really quite beautiful – sort of a male Shirley Temple.”2 “A sort of Gothic Shirley Temple. A Jewish Shirley Temple.”3 Looking at baby photographs of Marty you can see his point. Certainly the ringlets were in the right place. “I didn’t always look like this,” he would protest. “My mother tells me I was a very pretty baby with a little snub nose.”4 Even so, he would often later readily dismiss 1934 as “a bad year, nothing else happened.”

Martin Alan Feldman was a product of an honest East End upbringing. A melting pot of cultures and attitudes that instilled in him the value of money, the pain of not having much of it and the heart-pounding thrill of a colourful, cosmopolitan lifestyle. But from the very outset there was something of the outsider about him.

Marty’s Jewish emigrant parents had gratefully settled in London’s Canning Town after journeying from their native Kiev in the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic. “It’s a very stunted family tree,” he said. “It only goes back one generation. Even now I’m not too sure of it. But they were just peasants. I’d liked to have found someone spectacular in my past. I’d like to find one lovely idiot. I’d like a homicidal maniac as an ancestor. I wish I were related to Jack the Ripper. We can’t trace our madness back. The royal family know they’re mad, they’re lucky. How lovely to know you’ve been potty. Authentic lunatics. I like lunatics. I hate eccentrics. My grandfather on my father’s side aspired to be an artist, he re-touched photographs and called himself a painter but before that they were boring peasants, so I have to generate my own lunacy.” The past was meaningless to Marty: “A horse with blinkers on can’t see what’s going on either side, he can just see where he’s going. I can’t even see where I’m going. I can just see where I am!” Although at least he felt wanted. At first, at least. “My father and mother married when they were both sixteen and I came along when they were twenty-one,” he explained. “They had five years to think about it, so they obviously knew what they were doing when they produced me.”5

He would always display a charming, lyrical delight in his lot. He could fall into despair, anger or a heady mixture of both but, as a rule, his view on life was always positive: “When I was about two years old, I was so handsome,” he would say.6

Marty was an optimist, a gentle man and a cheerful Artful Dodger. He certainly needed to be. His childhood was a poor but happy one in which material things weren’t really that important. A family could get by simply by being a family. “I never suffered from poverty,” Marty remembered, “although our environment was far from affluent.” However, like Charlie Chaplin, Marty’s poor beginnings would stay with him throughout his life. Fame was important, fortune even more so, for Marty had experience of being at the bottom of the heap and he wasn’t planning on going back there. Still, if his parents could survive a Russian winter they could certainly survive the East End on a budget. Even when their family was extended to include a new, bouncing baby sister for Marty, namely Pamela, at the end of 1940. “He was a lovely brother,” she remembers. “There was nearly seven years difference between us so he could always get his own way with me. He would hold me over the banisters at home if I didn’t do what he wanted! I would spend time with my friends around Golders Green and he would pop down to make fun of us. He was madcap, even then.”7

“My parents were poor,” Marty said. “They were always slipping out of digs because they couldn’t pay the rent. But you never think you are poor when you are a kid. No one ever says there is nothing for you to eat tonight. You just don’t know that your folks haven’t eaten.”8

Marty lived through it happily, simply because he didn’t know or expect anything better. Years later, surrounded by the wealth that Hollywood had given him, Marty could be more damning of his humble upbringing: “It’s comparable to the East Bronx in New York or New York’s Lower East Side of thirty-five years ago,” he reflected. “The Jews who got on a boat and left Russia or Poland ended up either in the East End of London or in New York. It was a matter of which boat got out first.”9

In actual fact, the full extent of Marty’s poverty-stricken childhood fully depends on which account you believe. During his most successful period in Hollywood Marty himself endorsed the fact that his anxiety “likely derives from a Dickensian youth in London’s East End, the son of a Russian immigrant.”10 Writing shortly after Marty’s death, Barry Took remembered the facts slightly differently. “Marty was born to a moderately well-to-do Jewish family in London’s East End.”

Marty certainly had an affinity with New York. Particularly the jazz tradition. “I’ve been fiddling with music ever since the age of four,” he said. “Music informs everything that I do. I’m audibly orientated.”

Although life in Canning Town in the 1930s was scarcely comparable to the Bowery, it certainly stimulated him audibly. Unfortunately, the sounds were going to get much louder. Death and destruction was just around the corner for hard-bitten Londoners. When the war in Europe erupted in the autumn of 1939 the conflict might as well have been on another planet, but by 1940 the ‘phoney war’ was over and the East End was a prime target. The narrow streets and bustling marketplaces that had become Marty’s playground were now a “waste-land”. Barry Took asserted that: “When he was six years old the war came and Feldman senior departed for the RAF, and Marty and his younger sister, Pamela, were left in the sole charge of their deep-voiced, super-competent mother.”11 In fact, it was soon after his father’s departure that the young Marty was evacuated to live with a family near Nottingham. Along with millions of other threatened Londoners, he discovered a new, fresh, open-air life in the countryside. Peace and quiet replaced the drone of bombers and the yell of street-vendors. Muddy ditches and hayloft s replaced craters and shelters as the setting for his play. “I used to put on a one-man show for the local kids,” he remembered. “Chasing a butterfly and falling over, doing whatever I felt like. It made them laugh.” The experience would change his life. For the first time he actually realised where his food was coming from. A salt beef sandwich in the East End was one thing but when you had been patting the head of a friendly, dewy-eyed creature the day before you sat down to eat well-done, severed portions of it, that was something else entirely. “I realised that I was eating something that had been running round happily the day before,” he said. “It seemed immoral.” That attitude didn’t falter. At that young, impressionable age, Marty became a vegetarian, for good.

He was almost misty-eyed when recounting that pivotal moment for Dutch television in 1977. His vegetarian lifestyle was completely an issue of morals, not health: “It has to do with... when I was a child,” he revealed. “I was brought up in the slums of London, in the city, and in the city as a child you don’t see animals except cats, dogs, pigeons, horses. None of which you eat. When the war came I was evacuated into the country onto a farm and I got to play with the animals and one day George the rabbit was George, lunch.”

As usual with Marty, his persona as a comedian with the laughterinducing features meant that almost everything he uttered was greeted with a snigger. The studio audience in 1977 was no exception. He looked hurt and rather resentful but kept his focus and continued: “Really. And that was the end of it. I don’t mean it to be a joke. It’s a joke now. It’s a bitter joke to me but it was traumatic as a kid.”12

In fact, Marty had had his stomach turned off meat from an even earlier age, when his mother would force feed him Jewish staples of chopped liver and chicken as a child. As an adult he lived on a diet of eggs, salads, vegetables, spaghetti, bread, coffee and cigarettes. Even if the smallest bit of meat got in to his food he would turn green and throw up.13 Barry Took maintained there was a more rudimentary reason for Marty’s lifelong commitment to vegetarianism: “Later Marty was sent to a ‘Dotheboys Hall’ sort of boarding school, and his loathing for the food they served there was the start of a lifelong adherence to vegetarianism.”14

However, Took did remark that he found Marty’s commitment to vegetarianism later became variable to say the least. “We would go abroad on working holidays together,” he said. “Marty would try bits of the local cuisine. He was a geographical vegetarian. The further away we were from London, the more meat he would eat!”

School life had made Marty’s eating regime extremely difficult: “It was hard. At mealtimes, we weren’t allowed to leave the table at school until our plate was clean. Meat was always served so I spent most of the time stuffing my pockets with meat in order to smuggle it out of the building. I felt like I was digging a tunnel in a prisoner-of-war camp!” It may have been one life lesson that Marty never forgot but his formal education was a mess, and not simply because of the upheaval caused by world events. After the conflict Marty had returned to the trams-and-craters life in London’s East End. The family had survived the war and that post-war austerity that affected so many seemingly passed the Feldman clan by. In truth, they couldn’t sink much lower than they had, but Marty’s father had invested cleverly. A pushcart peddler made good, he had taken charge of a dressmaker’s and was making a real success of the business. So much so that he decided to give his son the head start he hadn’t had himself. As a result Marty single-handedly took on the British education system. “He put me into one school after the other,” recalled Marty ruefully. “All over the country. I was thrown out of a few and left others.” And it wasn’t just the food that turned Marty’s stomach. Whether it was Heathcote School in Danbury or an Orthodox Jewish public school, no educational establishment could keep him interested for long. “I ran away from one harsh boarding school three times. The fourth time they expelled me. That was what I was trying to tell them in the beginning: that I didn’t want to go to their school. But they kept bringing me back and beating me, bringing me back and beating me again.”15 Marty’s disjointed education also kept him apart from his sibling for much of the time: “I know he was very upset to be sent away to boarding school in Brighton,” says his sister Pamela Franklin. “It wasn’t that long after I was born and he always thought it was because of me. It wasn’t, of course. It’s just what people did in those days. He was a bit angry about that. Between the time he was aged eight and eleven we didn’t see much of each other at all.”

An inattentive and obstinate pupil, his academic prowess ranged from ninety per cent in an English test to a big fat zero in Mathematics.16 Despite this early aptitude for the written word, typically the British educational system still penalised the young Marty: “I used to write a lot of poetry. I was first punished for writing at the age of eleven. My school accused me of copying a poem I wrote. It wasn’t very good, but it scanned and rhymed, and it might have come out of a book of children’s verse or something. They said I wouldn’t be punished if I admitted I copied it. I said, ‘But I did write it,’ and so I got punished for writing. That may have gotten me on to it. The masochist in me may have said, ‘Hey! People punish you for writing – I’ll be a writer!’ So I started writing then.” Marty’s youthful imagination and delight in baiting authority led to a passion for fiction, even within his regimented homework assignments: “Writing came easy for me,” he explained. “I’d be asked to write an essay on what I did on my half-day’s vacation. Well, I didn’t do anything interesting. So I just filled the whole exercise book with a story that I’d made up – a child’s novel, set during the war, in which I parachuted into occupied France and captured a German general and brought him back. I filled the whole fucking exercise book with this. Again I was punished. They said, ‘That isn’t what you did.’ And I said, ‘No, but what I did was boring.’”17

Marty’s features were also getting the battle scars that would make his fortune: “My face reflects the sum total of the disasters of my life,” he said. “My eyes are the product of a thyroid condition caused by an accident when somebody stuck a pencil in one eye when I was a boy,”18 and “I got hit with a cricket ball, and some bones were re-arranged.”19His fragmented school days also taught him a vivid life lesson: selfpreservation: “When you are small and at school you have to move fast. I had to get the first punch in and then run like hell because if the guy could have caught up with me he would have killed me.”20 A quick wit also paid dividends in this: “You’ll find that most comics are small and physically strange-looking,” he said. “If you’re small and funny-looking and you don’t have great scholastic genius – which I certainly didn’t have – you retreat to the position of comic. It’s the only possible position you can take and survive among your peers. Unless you’re great at sports. At sports I was like I am at drums – enthusiastic but not talented.”21 He did, somehow, pass his eleven plus exam in spite of rather than because of his teacher. “There were good teachers,” he admitted. One in particular greatly encouraged his love of art and music. “But I know that many of the teachers that taught me were ill-equipped. Let alone to teach but to be outside of jails. They were lucky criminals who had never been caught. They were con men and bullies and all kinds of villains.”

His film publicity blurb in the 1970s would reveal that Marty had become “hooked on comedy” during this time, whether through simple survival in various school playgrounds or burgeoning interest in amateur dramatics. But comedy was actually more of an escape from formal education. Marty would as often as not skip lesson after lesson in order to sneak into his local cinema to see the films of his Hollywood-based idols: the Marx Brothers, Laurel and Hardy, Red Skelton, Danny Kaye. Even the ultra-rare opportunity to see Buster Keaton in full flow.

His love of comedy took him in directions far beyond the educational system he found himself trapped in, including his first attempt at being a stand-up comedian at the age of twelve: “I’d been to see Danny Kaye at the Palladium. Having seen Danny Kaye I thought what I had to do is quite simple. I have to sit on the edge of the stage and talk to the audience with a cigarette in my hand. I stole jokes from everybody. It was an amalgam from jokes I had nicked from Max Miller, Danny Kaye, Jack Carson, Mickey Rooney; people I had seen on stage. I performed them once at a Bar Mitzvah for pocket money. I didn’t see anything incongruous in a twelve year old smoking a cigarette and talking about my wife: ‘Now she’s a lovely woman, let me tell you about the kids...’ I couldn’t understand why they got annoyed with me!”

However, arguably his most prized and inspirational possession was a paperback copy of scripts from Take It From Here, a pioneering BBC radio comedy penned by the architects of the form, Denis Norden and Frank Muir, whom Marty would cite as influences throughout his career. Tellingly, his heroes were often writers first and foremost. He considered himself privileged to be counted within their number. Indeed, as a teenager and perhaps in petulant reaction to his school’s accusation of cribbing, Marty sat himself down and scripted his own episodes of Take It From Here.

“When I first started writing humour, I decided I would read everything I could on it to find out what I was doing. And that will totally destroy you. You read all these different theories of humour, and they all contradict each other... It’s all theory. No good. Books and theories about humour have rarely been written by people who practice it. Freud had theories of humour. Whether one questions those theories or not, I do question the standard of the jokes he quotes – they’re pretty bad. Yes, they’ll all work, but so will their opposites. None of them will define humour... All of the theories about humour are true to an extent, but then there’s a greater truth than that, and I don’t know what it is. There’s a kind of Zen of humour, and if somebody is going to write it, then they’ll have to write it from the Zen point of view. Except that Zen is noticeably humour-less – it really is.”22 Marty’s was an obsessed and precocious talent.

A 1970 profile of Marty by John Hall noted: “As a result of this early specialisation Feldman never made the science sixth. In fact he never managed to stay in one school for very long, and notched up twelve alma maters before his fifteenth birthday. It is his proud boast that he has been kicked out of some of the worst schools in London.”23 This was no myth either. Marty’s inability to follow the rules resulted in monthly upheavals to yet another leaky fountain of knowledge.

“I have been expelled a few times,” he remembered, “but many times it was suggested that it would be a good idea if my parents didn’t bring me back next term. I could never resist a dare. I would be ringing the bell and a teacher came in to class and said if you think that’s clever go and ring it outside the headmaster’s door. I knew that was exactly what I had to do. I had to pick up that big bloody bell, go and stand outside the headmaster’s door and ring it as hard as I knew how. The school did come pouring out. I did get whacked. There’s this kind of awful foreknowledge of what I do. It’s going to work out to be a disaster and yet I kind of commit to the disaster. Actually, I think I ought to be declared a disaster area.”

This lifelong feeling of alienation had stemmed from his fraught school days. “That goes back to being the only Jew in my class, being the alien,” he said. “That’s how I was treated. I should have been issued a green card then. When they had prayers, I was sent outside. I wasn’t allowed to be there for prayers. They gave me extra maths. That’s obviously how they thought of their religion – it was as complicated and as dull as maths. That’s the English attitude towards Protestantism: cold showers and mathematics. It’s totally sexless. Cold. The British produced a great number of mass murderers, you know? England and Germany. Passionless mass murderers. Little bank clerks. My neighbourhood doctor. They all have sort of bald, bony heads and wear pebbledash lenses and raincoats. You find out that nice little guy in fact slaughtered a hundred people and ate them or something. I think it has a lot to do with Protestant repression.”

At first he was an enforced and devout follower of the Jewish faith: “I got Bar Mitzvahed, the whole thing. I was very good. I learned Hebrew. I was very attracted to Judaism, to the ritualism, the theatre of Judaism. Like Catholics. They do it even better – it’s grand opera. The same country that produced Verdi produced Roman Catholicism. The costumes and the lighting are the same. I suppose some of my early feelings towards theatre were conditioned by going to synagogue and by the Hasidim who lived in the neighbourhood. They were always singing and playing the violins. They were like Sufis to me. I’m still attracted to Hasidim. I love them, although I’m no longer a Jew in any religious sense, and there is no other sense in which you can be one. It’s a love of magic that Jews have. Also, a natural sense of money! Jews are storytellers, too. I can’t think of White Anglo-Saxon Protestant storytellers that would go from village to village, telling the legends of the people, like the Jewish storytellers in the shtetls.”24 “My parents were very religious, very orthodox,” says Pamela Franklin. “When Marty was young he too was very orthodox. He went to the synagogue regularly with me every week on a Saturday. I vividly remember walking with him to the temple. We also attended Hebrew studies on Sundays. As he got older he became less and less interested. He was obsessed about getting into show business.”

In order to escape the sense of alienation of being a Jew in England during the Second World War, Marty’s parents took a drastic step, according to Barry Took: “Around this time the family changed its name – from what I don’t remember – to Feldman, a change which upset the sensitive Marty. It seemed to him like the loss of identity. Later came the bourgeois family home in North Finchley, and time spent at a sedate north London grammar school, Woodhouse, which contrived to push [him] into the tame kind of rebellion that was commonplace among middleclass youths in the late forties and early fifties.”25 As Marty testified: “There’s a lot of anarchy in my comedy.”26

This anarchy fully erupted during his school days. “I didn’t do Bible class because I was a Jew,” he remembered. “I used to get annoyed about this and get a Bible and put graffiti all over it. Some awful copperplate saint; some androgynous creature with his hand out pointing the way in an awful school Bible. I drew glasses and buckteeth and a moustache, and they didn’t like that. Again I got whacked for it.”

Marty’s personal rebellion would be far less pedestrian than most, but the continual attempt on his parents’ part to blur their Jewish roots rankled. It seems to coincide with his father growing prosperous. This attitude just made the young Marty even more cynical. “Jesus was Jewish, I suppose,” he said, “[but] he’s not the kind of Jew who would be accepted by the Hampstead Garden Suburb. He wasn’t a lawyer or a doctor or the kind of Jew my parents would have accepted. He was merely a saviour, which wasn’t a professional. You couldn’t have a brass plate.”

Marty’s niece Suzannah Galland says, “My uncle loved his father very much. My grandfather Myer was a very religious man and a very funny man, so although they didn’t play games Marty did grow up with humour. My grandfather did very well in business. He had a string of beautiful models modelling gowns for his fashion house. He would eventually become so successful that he could afford to buy himself a Bentley, but it was bang in the middle of a social change and Marty wanted to be part of the revolution.”27

As his parents became more affluent, Marty simply became more rebellious. He was completely disinterested in money and position: “By the time I was old enough to realise, we were doing OK.” It was too late for obedience. “Most comedians are either lazy or inefficient. By being the jester of the class I found I could get out of work at school. By doing that I found I didn’t have to compete. You know how competitive the school thing is. I’m basically non-competitive so I just sat there and went ya-boo-sucks.”28

Besides, Marty had long ago found his passion in life: jazz. With just two formal trumpet lessons he, once more, rejected education and taught himself: “I had a trumpet case and I had a bottle of gin. I hated gin. In fact it used to make me puke. But I used to resolutely drink it because I had read [pioneering jazz cornetist] Bix Beiderbecke used to drink gin. By some process of alcoholic osmosis, by the presence of a bottle of gin in my case, [I thought it] might turn me in to Bix Beiderbecke. I was the youngest bandleader in England. I had Marty’s Gin Bottle Seven. I wanted to have a treasured destiny at the age of fourteen. By the age of fifteen I had realised I didn’t have a treasured destiny, I only had a slapstick now. I’ve lived in that ever since.”

Jazz music was hardly the image his parents wanted. Particularly not when the lifestyle invaded their peaceful home: “One night I brought a lot of people back to this house; a load of musicians. A kind of orgy took place in this suburban house and my parents came home and found it. The police were called because a bird fell out of bed onto a broken glass. There was blood everywhere. It was like cleaning up after a murder. My parents came home in the middle of all this and said: ‘These are your friends? These people with beards and bare feet who play trumpets and take drugs and drink!’ I said: ‘Yes, they are!’ They said: ‘You’re giving us a bad name in the neighbourhood!’ So I left home. I left at my and their own volition. I had a choice [but] I knew that I could not go back to that home as long as I was with these people and I felt more at home with these people than I did with the suburban community.”

As throughout his life, Marty gravitated towards Soho and the jazz clubs, cafés and pubs that bred rebellion and the community of skippers: the waifs and strays who became his closest friends. “I’d built a house from deckchairs in Green Park. We would make a house, me and the bums that were with us – me and my trumpet. We would sleep in this tent-like little house made of deckchairs. You would stack them up to make a covering. I used to get up in the morning and blow ‘Reveille’ in the park. It was great. Tramps learn how to sleep in a park under cover. What appeared to be an empty park at five thirty in the morning suddenly was populated. All [these] startled figures would pop up out of the bushes!”

Sleeping rough and doss houses became Marty’s norm. “There were certain waiting rooms and certain stations that were fine. You could sleep in Waterloo. I don’t know why [but] the police were easier there. All you had to do was to have a ticket for a train, so you had a reason to be there and you could sleep there. Waterloo was also very near to the Sally Ann.” Indeed, the Salvation Army came to Marty’s rescue on several occasions. Until he was barred! “You used to tie your boots to the bedpost so they couldn’t get nicked,” he remembered, “and you used to put your jacket and trousers under the blankets so they couldn’t get nicked. So, you’ll be lying in this awful bloody dormitory. One night I was lying in my shitty pit with this smell of carbolic everywhere and a guy got out of the bed next to me and pissed on the floor. [This] was fairly common. I thought: ‘Well, that’s OK.’ I was very tired and drunk. I didn’t realise he had pissed on the floor under my bed. The next morning the guy on the door said: ‘You’re barred!’ And I said: ‘Why?’ ‘For pissing on the floor. There’s piss on the floor under your bed,’ and I said: ‘That wasn’t me. I wouldn’t piss on the floor!’ He said: ‘It’s there. You’re barred.’ Barred from the Salvation Army. It’s the point of no return, really!”

The solution was show business. “I answered an advertisement in The Stage that asked for a ‘personable young man’... and to enclose a photograph. I was fifteen. I enclosed my Bar Mitzvah photograph in fact, from two years earlier. I was going to get paid thirty bob [shillings] a week. I got hired, got on a train to Exeter and was picked up by a very strange looking guy. If Orson Welles were dying of cancer and bought himself a fright wig, he would have looked like this man. He was a hypnotist and he had a strange little wife of about twenty-five – a shrewish little bird. They were playing one-night stands in village halls. On the way back to the caravan where we were going to be staying they both groped me; I had never been groped by two people, never mind one male and one female. I found out they were both bisexual and fancied me from the photo. I fought them off. I said: ‘I don’t want this, I want to be in show business.’ They said: ‘What do you do?’ I said: ‘I don’t know. You asked for a personable young man. I’m young. I’m man, very pointedly, and probably personable. What do you want me to do?’ [He said]: ‘I thought you had an act.’ I didn’t have an act but I said: ‘Oh yeah, I’ve got an act.’ That night I walked on without any idea what I was going to do and tried to remember some jokes that I’d heard. While I was doing this, a lady in the front row started knitting and someone else had fallen asleep. I came off and cried, knowing that I had to go back to this caravan and be groped by these two strange creatures again. [For] the rest of the act I had to put on a record, ‘Legend of the Glass Mountain’, while this hypnotist pretended to hypnotise his wife and then pretend to hypnotise me. He couldn’t hypnotise either of us. We would go to a different town or village each day. In the morning, I would have to go round with posters to the local shops to persuade them to put the poster up. I would unload the scenery, put it all up, get on, do the show. After about two weeks I had developed about ten minutes of chatter. It wasn’t patter. It wasn’t comedy. I didn’t know what it was. It was conversation without anybody to talk to. They fed me on rough Devon cider, trying to get me pissed. If there weren’t enough people in the hall, he would refuse to do a show. He would be drunk every night and when we got back to the caravan he would try and rape me again. All this for thirty bob a week! I said: ‘Look, I’m going. I really can’t stand it.’ They paid me my thirty shillings in silver. My thirty pieces of silver. It was the night’s takings, in fact, and the guy said to me: ‘If you tell anybody about what we did, we’ll blacken your name and you’ll never work again.’ That was my first experience of professional show business. I thought it was all like that, which is why I stayed in it!”

However, this was one of many final straws for Marty. “I would try and go home occasionally,” he said, “but things would get in the way. I couldn’t live my parents’ life and they couldn’t countenance my way of life because it involved all kinds of disreputable carryings on. They were right from their point of view.”

At the age of fifteen and completely disillusioned with his place in life he dramatically upped sticks and tried his luck in France. Paris was the European centre of art, poetry and cool jazz. As often was the case in Marty’s life his natural desire to be at the heart of creativity completely over-took him: “Needless to say, I dropped out of school early,” he recalled. “You were supposed to make some half-hearted attempt at a higher education so that you would have some kind of career. Certainly that’s what my parents wanted for me. [But] there were too many things I wanted to do. I wanted to write. I wanted to paint. I went to Paris to write and paint. I thought that if I went there and hung out, the ghosts of Fitzgerald and Hemingway and Henry Miller would sort of rub off on me by osmosis.29 But it doesn’t happen by osmosis; nothing happens by osmosis. I discovered that in a year or so, during which I learned to get rid of the adjectives in my writing. I realised that the verbs or the nouns were important – either the trumpet or the rhythm section.”30

As usual every instinct and reaction to life’s ups and downs was equated to jazz music. But Marty’s rebellion, while dramatic, was reassuringly borne of middle-class boredom. Marty’s was a very British coup.

Chapter Two

“I won the award for being the best loser.”

Like most people between the cradle and the first kiss, Marty’s attitude was that no one else could understand what he was trying to do. A creative mind was already hard at work and a total devotion to silly things and silly people was clouding his vision wonderfully. His mind was full of great literature and majestic pratfalls, off -colour jokes and hilarious slow burns. He had been the class clown and the class joke. He was proud of both achievements.

Indeed, comedy seemed to be his chosen profession. However, rather than the spiralling linguistic trickery of his subsequent scriptwriting, Marty chose to tread the lonely path of the long distance stand-up comedian: “I tried it once, when I was fifteen. But you know the standup comic is a lonely figure who is put in the position of dominating the audience. The same impulse that makes you a stand-up comic probably makes you a dictator. It’s a very lonely way to make a living.”

But a living had to be made. His impulsive abandoning of the educational system was reckless and fun but the harsh reality was less amusing. Away from school and away from his family, Marty was residing in a disused hut in the centre of London’s Soho Square. The Artful Dodger had reared his head again and the excitement of a life living rough wasn’t enough to heat his beans of an evening.

He later admitted that he was something of a middle-class teenage rebel. His Jewish parents had worked their way up through the rag trade in the East End of London until they had owned their own shop. “I suppose I was a bit of a hippie,” Marty reflected at the end of the 1960s.1 More to the point, Marty was a romantic and an artisan to the soles of his wornout shoes. Paris seemed the natural place to be: “I got to Paris because I thought that’s where painters should go. With my trumpet under my arm wrapped in brown paper, because that’s what Bix Beiderbecke did. We got to Paris and I stayed there for about a year.” It was “a completely bizarre, exciting, great period in my life.” Paris was the city an artist really felt he had to experience in order to call himself an artist. Suffering for your art and peace of mind in London was one thing, suffering in Paris was a statement. Marty had little education, even less money and absolutely no French but he picked up a smattering of the language from American G.I.s studying at the Sorbonne although: “They never used to study. They used to sign on the first day, get their grants and get pissed the whole of their period in Paris.” One such G.I. was an American Greek sculptor by the name of “Speedy” Pappofatis. He was: “a very good sculptor – he ended up doing some work on the United Nations building – but he could never sell any of his work. I was student-looking then and used to hang around bars and accost likely looking American tourists. I would tell them I knew a very fine French sculptor and drag them back to his studio. He would put on a French accent and sell them bits of his work and I would get a commission on it. They would buy stuff from a genuine French sculptor but they wouldn’t buy it from a guy called ‘Speedy’ Pappofatis from Illinois!”

A general tout and dogsbody, Marty would model; even make attempts to sculpt but there was always more money to be had. At fifteen, he could be “three people in one day.” He was an assistant to a pavement artiste for a short time. “This guy had a perfectly viable theory that if you paint some pictures on the pavement and you are not sitting there then no one will drop money in the hat. So he used to go round about six in the morning, do about twenty different pitches and put a cap down.” Utilising the indigenous students as well as Marty, “One of us would take one of the pitches and just sit there. Tourists would go by, they would see someone sitting there and they would drop a coin in the hat. We were stand-ins for a pavement artiste. We would divvy up at night.”

“I worked various fringe operations – legal, semi-legal, some illegal activities,” he said. “The usual street hustles, which could never quite get me hanged but could get me sent to reform school if I was caught. I was never caught.” For Marty, Paris was also, naturally, a hotbed of jazz. Since he arrived in 1949, the nightclubs and bars had held a unique fascination for the teenager. He would often claim, with sincere pride, that he was “the world’s worst trumpet player” but it earned him a living, of sorts.