18,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: John Wiley & Sons

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Serie: Themes in History

- Sprache: Englisch

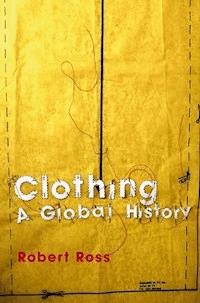

In virtually all the countries of the world, men, and to a lesser extent women, are today dressed in very similar clothing. This book gives a compelling account and analysis of the process by which this has come about. At the same time it takes seriously those places where, for whatever reason, this process has not occurred, or has been reversed, and provides explanations for these developments.

The first part of this story recounts how the cultural, political and economic power of Europe and, from the later nineteenth century North America, has provided an impetus for the adoption of whatever was at that time standard Western dress. Set against this, Robert Ross shows how the adoption of European style dress, or its rejection, has always been a political act, performed most frequently in order to claim equality with colonial masters, more often a male option, or to stress distinction from them, which women, perhaps under male duress, more frequently did.

The book takes a refreshing global perspective to its subject, with all continents and many countries being discussed. It investigates not merely the symbolic and message-bearing aspects of clothing, but also practical matters of production and, equally importantly, distribution.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 454

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Ähnliche

Table of Contents

Cover

Dedication

Title page

Copyright page

Acknowledgements

Illustrations

Picture Credits

1 Introduction

Structure of the book

2 The Rules of Dress

3 Redressing the Old World

4 First Colonialisms

5 The Production, Care and Distribution of Clothing

6 The Export of Europe

7 Reclothed in Rightful Minds: Christian Missions and Clothing

8 Re-forming the Body; Reforming the Mind

9 The Clothing of Colonial Nationalism

10 The Emancipation of Dress

11 Engendered Acceptance and Rejection

12 Conclusion

Index

For Janneke

with love

Copyright © Robert Ross 2008

The right of Robert Ross to be identified as Author of this Work has been asserted in accordance with the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

First published in 2008 by Polity Press

Polity Press

65 Bridge Street

Cambridge CB2 1UR, UK.

Polity Press

350 Main Street

Malden, MA 02148, USA

All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purpose of criticism and review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher.

ISBN-13: 978-0-7456-3186-8

ISBN-13: 978-0-7456-3187-5(pb)

ISBN-13: 978-0-7456-5753-0 (Multi-user ebook)

ISBN-13: 978-0-7456-5754-7 (Single-user ebook)

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

The publisher has used its best endeavours to ensure that the URLs for external websites referred to in this book are correct and active at the time of going to press. However, the publisher has no responsibility for the websites and can make no guarantee that a site will remain live or that the content is or will remain appropriate.

Every effort has been made to trace all copyright holders, but if any have been inadvertently overlooked the publishers will be pleased to include any necessary credits in any subsequent reprint or edition.

For further information on Polity, visit our website: www.polity.co.uk

Acknowledgements

I owe thanks to a number of people for their help in the writing of this book; first to the Netherlands Institute for Advanced Study, Wassenaar, its Rector, Wim Blockmans, its executive director, Wouter Hugenholtz, and its staff, particularly in the library. The half-year fellowship I enjoyed gave me the opportunity to break the back of the research and to begin the writing; to my own employers, Leiden University, and in particular to the department of African languages and cultures for their forbearance with work which does not centrally deal with the concerns of the department; to Anna Beerens, Jan-Bart Gewald, Mieke Jansen, Rudy Kousbroek, Kirsten McKenzie, Giacomo Macola, Mina Roces, Anjana Singh, Nettie Tichelaar, Ruth Watson, and Thera Wijsenbeek for references and comments on a number of sections; to seminar audiences in Basel, Sydney, Pretoria and Canberra who have heard, and made useful comments on, various of the chapters; to Polity for suggesting a topic which I would never have chosen myself and for their patience in awaiting the manuscript; to their anonymous readers for informed and helpful comments from which I have taken confidence and advice; and to librarians in a number of places, particularly in Leiden, for their help.

Above all, I have, and want, to thank Janneke Jansen, for continual encouragement, for constructive engagement, for her critical reading of the various chapters and her valuable advice and for much, much more. And that is only the academic side of things. The rest is far more important.

Leiden

Illustrations

1 World leaders in Evian, 2003

2 A village headman from the Moluccas, Indonesia, 1919

3 Corset advertisement

4 The De Vries family, Batavia, 1915

5 Indonesian nationalists

6 Girls in Mother Hubbards

7 Ratu Sir Kamisese Mara and General Rabuka, Fiji

8 A Christian village near Marianhill, KwaZulu-Natal

9 Herero woman dancing, Windhoek

10 Mustafa Kemal Atatürk

11 Kwame Nkrumah (left) with a member of his cabinet

12 Jaharwalal Nehru and Mahatma Gandhi

13 The New Look

14 James Dean in Rebel Without a Cause

15 Woman in a qipao

16 Girls in Islamic dress, Birmingham, 2002

Picture Credits

The publisher would like to thank the following for permission to reproduce the images in this book:

AFP/Getty Images (World leaders in Evian, 2003; Rati Sir Kamisese Mara and General Rabuka, Fiji)

Koninklijk Institut voor Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde (A village headman from the Moluccas, Indonesia, 1919; The De Vries family, Batavia, 1915; Indonesian nationalists)

Getty Images (Corset advertisement; Mustafa Kemal Atatürk; James Dean in Rebel Without a Cause)

Time & Life Pictures/Getty Images (Girls in Mother Hubbards; Kwame Nkrumah (left) with a member of his cabinet)

Museum voor Volkenkunde, Leiden (A Christian village near Marianhill, KwaZulu-Natal)

The Namibian National Archive (Herero woman dancing, Windhock)

© Bettmann/Corbis (Jawaharlal Nehru and Mahatma Gandhi)

Rex Features (The New Look)

Jamie Jones/Rex Features (Girls in Islamic dress, Birmingham, 2002)

Powerhouse Museum, Sydney (Woman in a qipao)

Every effort has been made to trace all copyright holders, but if any have been inadvertently overlooked the publishers will be pleased to include any necessary credits in any subsequent reprint or edition.

1

Introduction

Take the meeting of world leaders known as the G8, which met in Evian, France, in June 2003. It was a gathering which had important discussions to conduct, and important decisions to make. What is intriguing, though, is the fact that as they emerged to have the collective photograph taken, the political leaders of the eight most powerful countries in the world – though the Chinese were not there – all of whom were men, all wore basically the same outfit – dark suit, light shirt, tie, polished shoes. The Presidents of Russia, France and the United States of America, the Prime Ministers of Japan, Italy, Great Britain and Canada and the Chancellor of Germany had all adopted this uniform. So had the leaders of lesser nations who were allowed to put their case to the mighty, with two exceptions, the President of Nigeria and the representative of Saudi Arabia. Prince Abdullah Ibn Abdul Aziz Al Saud was in flowing Bedouin robes, Olusegun Obasanjo was in equally flowing Yoruba costume. But the South African, Thabo Mbeki, wore a suit as well-tailored as that of any of his confreres, as did the presidents of India, Malaysia and China.

1 World leaders in Evian, 2003

It is instructive, as a thought experiment, to wonder what a gathering of their predecessors four hundred years ago would have looked like. If it had been possible to gather the Kings of France and Spain, the Ottoman Sultan, the Shah of Persia, the Mughal Emperor, the Emperor of China, the Shogun of Japan and whoever might be given the eighth place, perhaps already the Stadhouder of the Netherlands, then there would have been no uniformity in their dress, even though, as in 2003, they were all men. Representatives from lesser powers, say the Alafin of Oyo, the Mwene Mutapa, leaders of the Iroquois confederacy, any remaining Inca notables, would only have added to the sartorial diversity on show. Moreover, none would be dressed as their successors now are.

Or take Hluhluwe, a small country town in northern Zululand, in a poor area of South Africa, living off sisal, pineapples, timber and rhinoceroses (via tourists), on a cold winter’s weekday in 2003. It could have been anywhere, except that I happened to be sitting outside the supermarket for half an hour or so. The men there were dressed in cotton trousers – occasionally jeans – shirts and jackets, often of leather. The women generally wore skirts reaching halfway between the knee and the ankle, though a few wore cotton trousers. For the rest, most wore jerseys and woollen jackets, although a very few had blankets round their shoulders, generally to carry a baby. Both men and women wore socks and mass-produced shoes, often sports shoes. A number of men wore woollen hats – it was June, after all – and the women generally had some sort of headscarf or other covering on their heads. The few boys who were not at school, probably because they had no one to pay for their fees and school uniforms, wore knee length trousers and shirts. I saw no girls hanging around there.

The sight was, somehow, South African in its details, in the way the headscarves were tied, in the woolly hats, in the length of the skirts, but even in this politically most ethnic, most Zulu, of areas, there was no one who wore anything which was in any way obviously ethnic, except perhaps for the rather too fat man who had on short shorts and sandals as only a white South African can, and two dancers in Zulu warrior gear who were attracting tourists by the game reserve. For the rest, the people of Hluhluwe had long been accustomed to dressing in a casual version of Western clothing. And no doubt, if they could afford it, the men would wear suits and ties to church on Sundays, and to other important events, and the women smart dresses.

This scene, simple enough, could be replicated in tens of thousands of shopping centres across the globe. There are of course all sorts of minor variations, and often quite substantial ones. In general, I would imagine, the women are more likely to diverge from the standard western norm than are the men.

These two vignettes from the early twenty-first century raise a question that is profoundly historical. How has this cultural homogenization come about? How has it come to be that when the President of France and the Prime Minister of Japan meet they are wearing essentially the same clothes, while their predecessors, say Henri IV and the Shogun Tokugawa leyasu, would not have been? What process has resulted in the people of Hluhluwe wearing clothes that are basically the same as those worn by men and women in Leiden, the Netherlands; in Salta, Argentina; in Bangkok; in Charleston, South Carolina; and indeed in most towns in most countries in the world? Just as importantly, why was it was the President of Nigeria and the first minister of Saudi Arabia who held out against the trend, if that is what they were doing? Where, and why, do large proportions of the population not wear variations of the common mode? Why are bodies covered, almost everywhere? Even in winter, there would have been much more bare flesh in Hluhluwe a century and a half ago. Is it true that women are more constrained by “tradition” than men, and if so how has that come about? Is it true, as Ali Mazrui commented thirty-five years or more ago, that “the most successful cultural bequest from the West to the rest of the world has been precisely Western dress”? He continued: “Mankind is getting rapidly homogenised by the sheer acquisition of the Western shirt and the Western trousers. The Japanese businessman, the Arab Minister, the Indian lawyer, the African civil servant have all found a common denominator in the Western suit.”1 It is to these sorts of question that I hope to give some answers in the course of this book.2

These answers can obviously be subsumed under the term “globalization”, itself a consequence of North American and European technical prowess, economic growth, imperialism and sense of cultural superiority.3 For all its potential modishness, this term does refer to a phenomenon which is real and important. Among many other things, notably in the speed of information movement around the globe, the material culture of the world has become (partially) homogenized. But to demonstrate this obviously requires a global approach, one in which the courts of King Chulalongkorn of Siam and the Meiji Emperor are as central as that of the King-Emperor Edward VII, in which, if it is necessary to find individuals, the most important are perhaps Kemal Atatürk, the Mahatma Gandhi and Jawaharlal Nehru, not Christian Dior, and in which the Herero long dress is as important as the New Look, probably more so because it has lasted much longer.

It should be obvious that I have not approached the writing of this book as a professional student of clothing, nor even more of the history of cloth. I was amused to discover Max Beerbohm’s comment on Thomas Carlyle, who wrote one of the first treatises on clothing, to the effect that “anyone who dressed so very badly as did Thomas Carlyle should have tried to construct a philosophy of clothing has always seemed to me one of the most pathetic things in literature.”4 In stereotypical gendered behaviour, it was my sisters, not me, who, when we were young, would regularly visit the costume galleries of the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, and I cannot remember having done so until I was well on the way to completing this book.5 Rather I am an African historian, and have taken pleasure from the idea that the continent will no longer be seen as a site of naked savagery. Specifically, I have long worked on colonial South Africa, and in that context I have written about the ways in which aspects of European culture were adopted, and put to their own uses, by the colonized. In this sense, I hope, this book is an extension of that work. If so, it must depart from the assumption that what people wear, like what they believe, can only in part be imposed from above, or outside. Rather, in the long term, the rules for external covering have to be internalized. This book is about how that has happened.

It should be clear that this approach is not the usual one in the history of clothing and dress. While I am in this a “lumper”, generally those concerned with dress and clothing are what would be termed “splitters”, if we were engaged in the study of natural, rather than social, history.6 In other words they emphasize the differences between the various costumes which they study, just as some taxonomists are more likely than others to see the organisms they study as belonging to different species. The reasons for this lie both in the most common reaction of almost anyone, at least in my experience, towards clothing and dress, which is to look for and to stress the particular, and also in the history of the discipline of dress history. On the one hand, the history of textiles has tended, naturally and rightly enough, to be about questions of production and, to some extent, distribution, in other words on the classic subjects of economic history, most notably of course with regard to the origins of the Industrial Revolution but also much more widely. On the other, dress history as such had its origins first in antiquarianism, both temporal and spatial, and then within the broader field of art history. Initially, the study of apparel was one of the ways by which art historians attempted to date, and perhaps to place, paintings.7 The finer the distinctions which could be made between what was being worn in a given year, and the next, and between the costume of one town, and the next, the better this task could be accomplished. As the discipline began to claim a higher status and to establish itself, this was primarily on the basis of work with collections, and on the basis of research into objects. There are of course dangers in such work. In general only the clothes from a tiny minority of the population, primarily from the highest strata, and in the relatively recent past, have survived. Moreover there are on occasion reasons why, even within this selection, certain sorts of clothes are overrepresented (for instance, silk, unlike wool, cotton or linen, cannot be recycled, and therefore garments made of such material are much more likely to have survived). I have the highest regard for the professionalism of such practitioners, who possess skills to which I cannot aspire. It should, however, be evident that their investigations into individual objects – their dating, provenance, manufacture and so forth – must lead to a concentration on the particular, and an avoidance of discussions of long-term similarities. In addition, many such scholars have been trained in schools of fashion, or are in other ways associated with them. The result can be an emphasis on the ephemeral, which fashion, important though it is and has been (as I hope this book will emphasize), of necessity is.

On the other hand, the drive towards the study of dress in general, and indeed dress history in particular, has been fed by ethnographic and anthropological enquiries. At their best, these are concerned with the structures of meaning which are given to dress codes. Thus one of the first, and probably still one of the most innovative, works in this genre, by Petr Bogatyrev on folk costume in Moravian Slovakia, took its inspiration from structural linguistics. However, in order to lay bare the structures in question it was necessary again to stress the differences between the dress worn by individuals of specific statuses – how the headgear of married women differed from that of the unmarried, and how the shame of unmarried mothers was marked sartorially, so that they married in other dress than putatively virgin brides, and so forth.8 Even without the structuralist arguments within which Bogatyrev was working, most ethnographic work on costume was long either in some sense ethno-nationalist or effectively “othering” its subjects. It was rare for the student of ethnographic material culture, in which dress should be included, to follow the admonition – admittedly made only in 1996 – of Claude Lévi-Strauss that “if we really wanted to display the ethnography of New Guinea, we should display a Toyota alongside the masks”.9

In one respect I am attempting to follow the conventional definitions.10 In these, distinction is made between, on the one hand, “dress”, which refers to the complete look, thus including for instance hair styling, tattooing and cosmetic scarification as well as items of apparel, and, on the other, “clothing”, which refers to the items of apparel, generally but by no means always made of some form of textile, leather and so forth. Further, “costume” is used sparingly, and to refer to dress which is donned in order to demonstrate, unambiguously, a specific identity. Finally, there is “fashion”, which of course is not specifically related to dress, but which refers to those things, material or otherwise, which at any given moment are, according to the Oxford English Dictionary the “conventional usage in dress, mode of life, etc., especially as observed in the upper circles of society”. This is a definition which only holds good if the “upper circles of society” are taken very widely, to include, for instance, pop singers just as much as – currently much more than – duchesses. Who sets the fashion can change as quickly as the fashion itself, but the whole point of fashion is that it changes fast, and works to include and to exclude those who do, or do not, adhere to its dictates.

What is clothing for? The Germans describe the uses of clothing as Schutz, Scham and Schmuck – protection, modesty and ornament. These are all relative, even the need for protection against the elements. The inhabitants of Tierra del Fuego, which would seem to be one of the harshest climates in which humans have lived, were usually close to naked, and presumably coped with their need for warmth without clothing. Of course, it is in general much better to be scantily dressed when wet, as the cooling effects of water are exaggerated by soaked clothes. As for the rest, modesty is close to a human universal, and the end of innocence was signified, not only in the Book of Genesis, by the putting on of clothes. What constitutes modest dress, however, could vary from the leather cap covering the glans of the penis, with which a Zulu gentleman, in the past, was decently dressed, to the full body veil, the burqa, of Afghan women. There are equally those who, at a given moment, may wish to flaunt their bodies, rather than conceal them. And as for ornament, the malleability of fashion over the centuries has been extreme. Universals of male and female beauty simply do not exist, nor are there ways to predict what will be seen as enhancing that beauty.11

Though clothing then protects our bodies against the elements and against the unwanted gaze of our fellows and attracts the wanted gaze, it nevertheless does more. It is one of the ways in which we make statements. It forms a language, if a restricted one. There are relatively few things that can be “said” through clothes, but they are very important things. Essentially, people use clothes to make two basic statements: first, this is the sort of person I am; and secondly, this is what I am doing. Such claims, for that is what they are, need not necessarily be true – a sign has after all been defined as something through which it is possible to lie12 – and often include a considerable degree of wishful thinking. They may also be forced upon the wearer of the clothes by some other people, as in the case of those slaves who were not allowed to wear shoes or a hat or, in parts of the Arabian peninsula, a full facial veil, and the choices are almost always constrained by economics. Furthermore, like every language, verbal or otherwise, clothing at any given time and place has a grammar, usually constructed out of a set of oppositions, and can always be analysed as a semiotic system.13 This requires, though, that clothing systems be treated, for the purposes of analysis, as static, while in fact, like the grammars of all living languages, they are in continual flux. Indeed sartorial grammars are likely to change faster than those of many other sorts of language because one of the things that people often want to make clear through their clothing is that they are up to date and in fashion.

They are also languages which have to be learnt, either as a child or as a (young) adult. This may lead to a situation of bilingualism, and potentially interesting moments of “code-switching”, or to the fairly complete replacement of the one code by another. There are two points which need to be made on this: first, individuals can make clear statements by wearing clothes from one sartorial idiom in circumstances which would really call for another; and, secondly, like all those who learn a language, they can make mistakes, which may lead to embarrassment. This may, of course, be a consequence of the fact that dress codes, indeed like verbal and all other codes, are not necessarily constant across all sections of even a “monolingual” society. There are, in other words, usually interacting dialects. And just as it is necessarily possible to understand the meaning of even the most personal piece of verbal art,14 so individual choice in clothing – what I feel happy in, what suits me – can only exist within the contours of the total system, one which may be more or less restrictive of that choice.

There is of course another side to this. As with all language it is possible to be misunderstood, wilfully or otherwise. Indeed it is probably easier for mistakes to be made with non-verbal languages than with verbal ones. There are circumstances in which people do not realize what the message they are sending out may be, or even that they are “saying” anything at all. The failure of communication can cause major difficulties. As against this there are moments in which people are making claims through their clothes which are simply thought presumptuous, and are not accepted. Such occasions can lead to ridicule, to great embarrassment and to considerable social tension.

The things that people say, or are forced to say, through their clothing are thus above all statements about an individual’s identity, which is of course continually shifting, being manipulated and reformulated, by clothing as much as by anything else, and which is likely to be dependent, in part, on the situation in which people find themselves. They are thus about gender, social status, age, occupation and so forth. Like the axes of multivariant statistical analysis, these may be stronger or weaker, and are, to a greater or lesser extent, correlated with each other, so that it may be possible to determine which is dependent on which, and to what extent. Within these, however, one axis is ever-present, namely that of gender. It is hard to conceive of an outfit worn by an adult, anywhere in the world and at any time, which does not in some way, blatantly or subtly, pronounce the gender of its wearer, and this even when the cut of the clothing is ignored.

In this book, I have attempted not to be lured into value judgements on either the aesthetics or the economics of clothing (or indeed on the political or other statements which the wearers of clothes use them to make). There has, however, been a strong streak of puritanism within the analysis of matters sartorial. Thomas Carlyle, in his Sartor Resartus, commented that the “first purpose of Clothes … was not warmth or decency, but ornament”.15 So far as can be judged, given the structure of this work, in which it is difficult always to be certain which opinions are meant to be seen as Carlyle’s own, this was something to be deplored. Marx, as we shall see, was equally critical of the styles of clothing of his day. Again, and more explicitly, Thorstein Veblen saw extravagant clothes as part of the ways in which those who could afford to do so demonstrated that they did not need to labour. It was not a tendency of which he approved.16 More recent authors, notably Pierre Bourdieu17 and Mary Douglas18 from among the canonical theorists, have analysed the ways in which particular societies – what is known as Western, in Bourdieu’s case that of France – have used clothing in the creation and the marking of social differentiation. This is of course a process which is in fact universal, and was never uncontested, although as Mary Douglas commented, consumption was not necessarily competitive but could also be used to allow inclusion. However much those who wished to determine the structure of society might wish it otherwise, the establishment and marking of status gave opportunities and goals for those who wished to take on a better position, as well as for those who wished to deny them the possibility of social mobility. In this sense, the history of most, though not all, hitherto existing sartorial regimes has been the history of struggle – class, gender-based, ethnic or national.

Structure of the book

In this book, I will discuss the history of sartorial globalization from approximately the sixteenth century until the early years of the twenty-first. In chapter 2, I attempt to give a summary survey of the ways in which, some half a millennium ago, the rulers of societies from Peru eastwards to Japan attempted to impose rules correlating, by decree, social status with forms of dress. The regulations, which covered much more than just dress, are collectively known as sumptuary laws. The chapter also discusses how, particularly in Great Britain and the Netherlands, such laws came under fire, and slowly disappeared, allowing the development, much more than before, of a demand-driven economy, at least in clothing. In chapter 3, I discuss how, in England and France above all, the later eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries saw the emergence both of a culture of fashion and of many of the characteristic features of later European dress. In particular, this was the period of what is known as the “Great Masculine Renunciation”, by which male dominance in the public sphere was signalled by sober, mainly dark clothing, and the exclusion of women from public affairs by the brightness of their clothing, and indeed the impracticality of much of what they wore.

Chapter 4 deals with the first expansion of the European sartorial regime outside the European peninsula. Particular attention is paid to how, on the one hand, the early English and Dutch colonists in India and the Indonesian archipelago began by accepting the mores and dress of those among whom they lived, but increasingly, as the colonies became further established felt, on their own skins, the pressure to conform to more general European norms. The further development of this process is described in chapter 6. On the other hand, in the great European colonies of the Americas, South and North, European dress styles were quickly part of the structure of colonial rule, although, as the movements for independence developed, the first forms of colonial nationalism in dress came into being, particularly in the British North American colonies, where resistance against imperial domination was signalled by the demonstrative wearing of “home-spun” cloth.

The spread of European-style clothing throughout the globe was a consequence, in the first instance, of European economic and political power and its associated prestige. However, this could only be achieved through the development of more efficient methods of production and, notably, distribution. In chapter 5, I discuss the introduction of various forms of new distribution and production techniques, notably new ways to provide efficient sizing of clothing, through the tape measure, the development of mail order businesses, the sewing machine and the paper pattern, all first used on a wide scale in North America. In addition, there was the large department store and the beginning of shopping as a leisure activity. Together with the establishment, in Paris, of a competitive market in women’s haute couture (which paralleled the more understated London-based male tailoring industry), and eventually the introduction of ready-to-wear fashion, these trends created the conditions for the clothing market of the developed world in the twentieth century.

The following chapters deal with the uneven adoption of European clothing outside of Europe. In essence, they revolve round the paradox between, on the one hand, the assumption that modernity, in its many facets, and treatment as equals with colonial and other rulers required the adoption of European attire and, on the other, the potential use of African and Asian sartorial symbols to signify nationalist resistance. In chapter 6, I continue the discussion of the sartorial history of the major colonial settlements, arguing that in a number of places, notably in Australia and Latin America, modernity demanded the capture of costume by the suit and the dress, but that this was at best partial. In India and Indonesia, in contrast, European clothing rules might be used within the contexts of local political struggles, but very often it was some version of Asian dress which was employed to make the points of independence. Missionaries, who were among the major spreaders of European cultural norms to other continents, also mainly propagated the sort of dress they were themselves used to in their home countries, although there was often a distinction made between the dress of the missionaries, male and especially female, themselves and that which they allowed their converts to wear. As missionary converts were so frequently at the forefront of anti-colonial nationalism, this could only lead to considerable tensions.

It would be mistaken to believe that the adoption of European attire was inevitably or even primarily a consequence of colonialism. In many of those regions which avoided formal colonization, autocratic rulers required of their subjects that they adopt what was seen as modern clothing, on the assumption that by changing their outward appearance they would also change their habits of mind. As chapter 8 argues, this was the case in eighteenth-century Russia and in twentieth-century Turkey and Iran, and also, though in a less forcible way, in post-Meiji Japan. Perhaps it was the fear of modernity and its accompanying political message which kept colonial rulers from propagating European dress. However, as chapter 9 shows, the political desire for acceptance, an integral part of anti-colonial nationalism, generally led colonial elites to stress their own respectability, in part by adopting the dress of their rulers.

The clothing of the West, to which many outside Europe aspired in their various ways, was, of course, not static. In chapter 10, I discuss a number of the major shifts. While male formal clothing has remained relatively static, clothing for women has changed drastically, becoming much looser and much more revealing. In particular, the old prohibition on women wearing trousers has disappeared. In general, indeed, there has been a relaxation of rules and what was once considered informal wear – including the lounge suit for men – has become acceptable in settings where previously it would have been unthinkable. At the same time, the distribution of clothing in a whole variety of chain stores has become much more sophisticated and much more global, while the production of ready-to-wear garments, as always seeking out the locations for cheap labour, has to a remarkable extent relocated to parts of Asia.

Nevertheless, the globalization process has not been complete. In the last substantive chapter, chapter 11, I discuss how the assumption of Western clothing, or at least particular versions of it, has been tempered by forms of cultural nationalism, by the desire of men to control women and by religious constraints. As a result, in many parts of the world the extent of Westernization has been heavily influenced by considerations of gender. This has led, certainly among Muslims but also in much of Africa, to the creation of alternative modernities, in which a number of the precepts of the assumed homes of modernity, in Europe and North America, are at least partially rejected.

Notes

1 Ali A. Mazrui, “The Robes of Rebellion: Sex, Dress, and Politics in Africa”, Encounter, 34, 1970, 22.

2 For some comments on this phenomenon, see C. A. Bayly, The Birth of the Modern World, 1780–1914, Oxford, Blackwell, 2004, 12–19; see also Wilbur Zelinsky, “Globalization Reconsidered: The Historical Geography of Modern Western Male Attire”, Journal of Cultural Geography, 22, 2004.

3 In this book, I take these phenomena for granted, and do not, except incidentally, expand on them, or attempt to provide explanations for them. Places to start which are as good as any, and much better than most, would include Bayly, Birth of the Modern World and A. G. Hopkins (ed.), Globalization in World History, London, Pimlico, 2002.

4 Max Beerbohm, “Dandies and Dandies”, in The Incomparabel Max Beerbohm, London, Icon, 1964, 18, cited in Michael Carter, Fashion Classics: From Carlyle to Barthes, Oxford and New York, Berg, 2003, 10.

5 Our father worked in the Natural History Museum, next door, and we were thus frequent visitors to the South Kensington Museum complex.

6 Even Margaret Maynard, Dress and Globalisation, Manchester, Manchester UP, 2004, tends in fact to stress difference, rather than the basic convergence which lies at the heart of globalization.

7 Lou Taylor, The Study of Dress History, Manchester, Manchester UP, 2002, 116. James Laver, long curator of clothing at the Victoria and Albert Museum, London, and one of the founders of costume studies, wrote that he was drawn to the subject because “I wanted to date the pictures”. Cited in Carter, Fashion Classics, 121.

8 Petr Bogatyrev, The Functions of Folk Costume in Moravian Slovakia; translated by Richard G. Crum, The Hague, Mouton, 1971.

9 Cited by Charles Bremner, article entitled “Chirac’s Monument for Paris”, in Times Online, 17.6.2006.

10 These can be found, for instance, in Mary Ellen Roach-Higgins and Joanne B. Eicher, “Dress and Identity”, first published in Clothing and Textiles Research Journal, 10, 1992, 1–8, and conveniently found in Mary Ellen Roach-Higgins, Joanne B. Eicher and Kim K. P. Johnson, Dress and Identity, New York, Fairchild Publications, 1995, 9–11.

11 For an idea of how things have changed even in North America, Peter N. Stearns, Fat History: Bodies and Beauty in the Modern West, New York and London, New York University Press, 1997. For similar analysis in the world of high fashion, see Valerie Steele, Fashion and Eroticism: Ideals of Feminine Beauty from the Victorian Era to the Jazz Age, New York and Oxford, Oxford University Press, 1985, esp ch. 11.

12 Umberto Eco, A Theory of Semiotics, Bloomington and London, Indiana UP, 1976, 7.

13 Famously, Roland Barthes, The Fashion System, New York, Hill and Wang, 1983 (translation of Système de la mode, Paris, Seuil, 1967); also Marshall Sahlins, Culture and Practical Reason, Chicago and London, Chicago UP, 1976, esp. ch. IV.

14Finnegan’s Wake might, I suppose, be an exception.

15 In the Oxford UP edition (Oxford, 1987), 30.

16 First published by Macmillan in New York, 1899, and reprinted with great frequency ever since.

17Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste, trans. Richard Nice, Cambridge, Mass., Harvard UP, 1984.

18 Mary Douglas and Baron Isherwood, The World of Goods, New York, Basic Books, 1979.

2

The Rules of Dress

Since clothing is inescapably a demonstration of identity, wearing clothes – or for that matter not doing so – is inevitably a political act, in the widest possible sense of that word. There are circumstances in which that politics is more blatant, or more contentious, than in others. Generally men and women say things, through their clothes as well as in other ways, that are acceptable to the mass of their fellows around them, and to the powers that be, and it is in the interest of those who hold power to make that daily practice an unexceptional and unthinking routine. In general, when we get dressed in the morning, we do not think of that as being as political as, say, voting or rioting. All the same, conservatism is just as much a political choice as any radical rejection of the status quo; it is just much more common.

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!