9,59 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Batsford

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

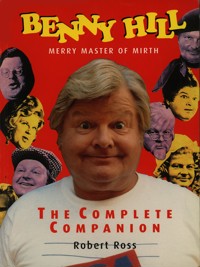

Benny Hill is the best known and best loved British comedian on world television - from the USA to the Pacific Rim. Feted for his unique brand of coy awareness, innuendo and saucy songs - but seemingly out of favour in his homeland before his death - Benny Hill can now be rated as having had one of the foremost careers in comedy. Robert Ross tracks Hill's career through the landmark Independent Television specials, early parody sketches for the BBC, film appearances, radio shows and recordings - including the No. 1 hit 'Ernie, the Fastest Milkman in the West'. Ross examines Hill's skillful use of the fledgling TV medium, and celebrates the support of his regular back-up team (Bob Todd, Henry McGee and Nicholas Parsons). The truth is revealed about Hill's Angels and the alternative comedy backlash that saw Hill pushed off the small screen in the UK. Benny Hill is the ultimate guide to the most widely recognised funny man since Charlie Chaplin.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Ähnliche

BENNY HILL

Merry Master of Mirth

THE COMPLETE COMPANION

Robert Ross

DEDICATION

To that great character actor, Norman Mitchell, a vital part of the indispensable band of players who made postwar British film and television such a rich treasure trove of delights. A wonderful friend, encouraging voice and cheerful spirit, you won’t find your name anywhere beyond this page, but this book is for you, Norman.

First published in the United Kingdom as an eBook in 2014 by Batsford 1 Gower Street London WC1E 6HD An imprint of Pavilion Books Company Ltdwww.batsford.com © Robert Ross 1999

First published 1999

The moral rights of the author have been asserted.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the copyright owner.

eBook ISBN 9781849942584

FOREWORD

‘He touched the funny bone of the whole world!’

Henry McGee

‘One thing that should be mentioned about his career is its sheer longevity – it was quite amazing. He was an extremely generous, kind man. Anything he set his mind to, he could do. His work had to be just right but he was always modest. He was a kind, lovely man whom I miss greatly – a great liver who lived his own way.’

Peter Charlesworth

‘That small group of people who worked with him, we would have done anything for him, because we really did love him. He was totally unpretentious, kind and all the things that weren’t like the man the press made him out to be. A great man, a wonderful man, and an enormous talent. I know I’ll go to my grave knowing my shows will be screened all over again – when they’re all watching it on kid’s television in 2090.’

Dennis Kirkland

‘Benny was great fun to work with.’

June Whitfield

‘I think he had this deep concern that some people hated his comedy because it was branded sexist. Benny continually said, ‘My comedy is not like that – I never chase the girls, the girls chase me!’ He was marvellous.’

Phil Collins

‘Benny was imbued with the knowledge and understanding of comedy tradition. He knew instinctively as a professional, and learning from others, what was right for his work. People to this day, say, “Oh, Benny Hill was so politically incorrect.” Well, maybe some of it isn’t acceptable by today’s standards, but if you say, “Was Benny Hill a funny man?”, the answer is “Yes, he was.” That’s all you need to know. He was of the music hall and the saucy postcard. He wasn’t consciously trying to offend, he was simply of his time, and that humour doesn’t date, however much our moral consciousness may change. He made millions laugh – end of story.’

Nicholas Parsons

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I owe tremendous thanks to Benny’s major BBC collaborator, Dave Freeman, and major Thames Television collaborator, Dennis Kirkland, for giving so much of their time and support to this project, also to Ian Carmichael, Peter Charlesworth, Phil Collins, Pamela Cundell, Nicholas Parsons, Graham Stark, Frank Thornton, Stanley Unwin, June Whitfield, Alec Brgonzi and Norman Rossington for their incisive, affectionate memories. Thanks also to Henry McGee, Gary Morecombe for his enthused encouragement, Barry Took for being such a legend and still having time for a newcomer like me . . .

Thanks again to Mr Richard Reynolds, my main man at B.T. Batsford, for continuing to pay me for something I would probably (I said probably) do for nothing, his assistant Andrie Morris, Max Tyler of the British Music Hall Society for pointing me in the right direction, those gloriously helpful folk at the British Film Institute Library, and latterly those other helpful folk at the Newspaper Library in Colindale, Alan Coles for a wonderfully dodgy copy of a wonderfully dodgy movie, that cool dude Rick Blackman for a cool dude-like programme for Fine Fettle, the late George W. Brown and my selfless friend Maxine Ventham of The Goon Show Preservation Society for invaluable information regarding Third Division – Some Vulgar Fractions, David Graham of Comic Heritage for valued support, me darlin’ Annalie Howlett for those glorious university days (remember when a session in The Vulture’s Perch seemed much more attractive than an evening of Benny Hill at the National Film Theatre?), Mum, Dad and Fiona for everything, and a fond farewell salute to Mr Cool himself, Frank Sinatra, who, apart from touching the human soul with everything from ‘One For My Baby’ to ‘That’s Life’, was a dedicated Benny Hill fan. Sock it to ’em ....

Stills are copyright to the production comapanies as credited in the accompanying text. The author would like to thank the British Film Institute, The BBC, Pearson and Canal+ for their help with illustrations.

INTRODUCTION

‘In relations between the sexes, the male is always disappointed.’Benny Hill

As Jimi Hendrix some time before 1970, a big-wig at RCA in 1977 and some bloke at Parlophone in 1980 all reputedly said: to die young is the best career move you can make. Benny Hill, for many years British television’s most successful comedian, died in 1992 at the age of 68. His youth and golden years gone, Hill was trapped in a twilight zone, rejected by the new blood of programme planning, held up as the epitome in tired, old-fashioned and offensive comedy by the new breed of comedian, and fast disappearing from the collective consciousness of the new generation of home viewers. While Tony Hancock, Eric Morecambe and Peter Sellers saw their legends soar and Frankie Howerd was riding the crest of a wave with renewed student stardom, Benny Hill had become the forgotten giant of British comedy.

In over a hundred countries across the world, the story could not have been more different. From Angola to Belgium, his shows were screened constantly. In France, his genius for mime was considered to be on a par with Chaplin and Keaton, in Russia his television shows were one of the few Western images to break through the Iron Curtain, and most importantly of all, in America he was by far the most popular comic import with his classic ITV Thames Television shows re-edited for repeated prime-time screenings. However, despite a strong, loyal following in Britain, the work of Benny Hill is still in limbo, stereotyped and castigated as embodying all that’s bad about British comedy.

But there was far more to his work than a never-ending line of suspender-clad dolly birds. This book will attempt to redress the balance by simply detailing the varied and endearing work of one of Britain’s best-loved clowns. Unlike biographies written by those family and friends close to Hill, this book is not a life story, nor is it a hagiography of the man – indeed, it’s impossible to deny that in later years, with his freedom restricted by the moral minority, Hill’s comedy became jaded and uninspiring. But writing all his own material, performing it with pride and embracing a trusted, tested troupe of colleagues, Hill was the all-conquering Citizen Kane of his own Xanadu before Thames Television finally pulled the plug.

His much-celebrated work for Thames between 1969 and 1989 typifies his enormous contribution to popular culture, and programmes from his 1970s golden age capture him at his assured peak. However, it must not be forgotten that Hill was the first comedian to attain stardom through the medium of television with his hugely popular BBC series from 1955 – programmes that, due to both the BBC’s distaste for all-out smut and the more restrained social climate of the time, allowed Hill to cleverly inject innuendo into his comedy. His radio assignments of the 1950s reveal a fine patter comedian in the mould of Max Miller, excellent character work opposite Archie Andrews, and latterly, the starring vehicle Benny Hill Time, which, heard today, reinforces the brilliance of his 1960s writing. Hill attempted cinema stardom with one of the last Ealing comedies, played Shakespeare, sparred with Michael Caine in an archetypal swinging sixties heist comedy and soared to number one in the British pop charts with his comic lament, Ernie (The Fastest Milkman in the West).

Unlike the ensemble dexterity I have previously tackled in The Carry On Companion and Monty Python Encyclopedia, this is a study of one man’s career. Regardless of the familiarity of his regular team, Benny Hill single-handedly summed up a tradition of saucy sea-side-postcard comedy, delivered at breakneck speed, peppered with knowing grins, rustic comments and innuendo-drenched songs. While the aim of this book is to present in full detail all the television, stage, radio, recording and cinematic ventures which made up Hill’s career, personal autobiographical information will be scattered between the dates and cast lists, sometimes to back up a point, or merely to highlight for the reader what Benny Hill the man was up to, as opposed to Benny Hill the comedian.

Totally aware of his own limitations (although his acting in the film Light Up the Sky! is a revelation that was sadly never repeated), Hill’s ambition was simple. From watching touring revue shows docked at Southampton, Hill remembered: ‘I used to watch comedians in shows like Oo La La always surrounded by pretty girls. That’s going to be the life for me one day!’ ‘The girls’ – like Bob Todd, custard pies or clown shoes – were just part of the act, but in the end they would prove to be his downfall. Despite the fact that Hill correctly argued that ‘My would-be lovers never succeed. A man who succeeds is not funny. A man who fails is funny ... if my sketches teach anything it is that, for the male, sex is a snare and a delusion. What’s so corrupting about that?’, his shows were axed in 1989, to the anguish of his fans and the delight of those who thought him politically incorrect. This book will look at the evidence and opinions from both sides of the argument, as well as Hill’s continued popularity with 100 million viewers in over eighty countries and his place in the annals of British comedy heritage alongside other beloved losers, such as Basil Fawlty, Harold Steptoe, Derek Trotter, Victor Meldrew and Anthony Aloysius St John Hancock.

When Sue Upton called Benny ‘the hapless clown’, she was dead right. Here was a comic talent without malice, bumbling through his own tightly controlled comic universe with the sole aim of making us laugh. He succeeded beyond his wildest dreams. This is the story of one towering comic figure who dominated British television entertainment for over forty years. His name may still be held in unjustified contempt by some, but his legacy, unfolded here, tells a tale of struggle, hard work and sheer talent.

BLUE BENNY HILL:

The early days of a comic legend

‘I’m the saucy comic!’Benny Hill

Benny Hill was destined to became the most universally successful comedian of the modern era. Marching the well-worn path of the European clowning tradition of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, he reshaped visual antics from his childhood cinematic heroes like Buster Keaton, Harry Langdon and, most importantly, Charlie Chaplin. The mixture included BBC radio snatches of music hall comedian Max Miller-like innuendo, thrilling early visits to local stage revues and the healthy tide of Donald McGill’s saucy seaside postcards coming in from Brighton. A transatlantic edge was grafted onto the sub-consciousness with influences from New York arriving at his hometown port of Southampton. The end result: the only British comedian of the post-war era to fully crack the international market, arguably one of the most instantly recognizable British icons, and the one clown who can rightfully challenge Chaplin for his crown.

Born Alfred Hawthorne Hill in a flat above a lamp shop in Bernard Street, Southampton, on 21 January 1924 (not 1925, as several reference books and Hill himself would have had us believe), he was the youngest son of Alfred and Helen. Performance was clearly in the blood of Hill’s family. Helen’s sister, Louise Cave, had been a semi-professional singer, his father’s father, Henry, had been a street clown, his father’s brother, Leonard, had been killed in a circus high-wire accident, and father Alfred Snr himself, born in Leytonstone, London, in 1894, had run away from home at the age of 16 to join in the excitement of Fossett’s Circus. Not surprisingly, throughout his life Benny Hill loved the small-town country circuses of France and Spain. His earliest memories were of his mother making him a clown suit out of an old pair of pyjamas and of his father donning the old make-up and walking on his hands up the stairs. This clownish sense of the absurd contrasted with the military strictness which earned Alfred Snr the title of ‘The Captain’ from his children.

Hill’s father’s life was marred by hardships, near misses and abandoned opportunities. His career in entertainment was prematurely curtailed by First World War service, and having fought on the Western Front, been gased in France at the age of 19 and survived a period as a prisoner of war in Belgium, he nursed an understandable hatred for authority shared by many of his shattered generation, promised homes fit for heroes, but returning as heroes fit for homes. Alfred had met and married Helen Cave in 1920, when he was a clerk at Toogoods Rolling Mills. In the same year as his marriage, a further failed business prospect had really turned Alfred sour – for he was now the sole employee in a company which would make a certain Jack Stanley a millionaire. Alfred had been offered a partnership in the firm, but couldn’t borrow the necessary money from his father. The business, a backstreet affair selling surgical appliances, abdominal supports, vigour-inducing medicines and contraceptives, dealt with many customers by post. With a new wife and just about to start a family, regular pay was far more important than risky business ventures.

Leonard Hill was born in 1921, followed by young Alfie Hill three years later, and sister Diana in 1933. They spent their childhood in a small terraced house, 164 Wilton Road, Southampton, enchanted by their mother’s readings from Bubbles annuals and other Christmas books – throughout his life, Hill maintained that the Giant in Pompety Finds a Needle was the most terrifying creation in literature.

The Future Looks Bright!

As a small boy, Benny faced taunts from schoolyard baiters along the lines of ‘Hillie’s dad sells French letters.’ Latching onto these cheeky jibes, piecing together limited sexual knowledge, and in the clichéd tradition of all great comedians, playing the classroom fool to win appreciation, Hill developed a knowing way with smutty comedy to entertain his contemporaries – he used this technique for the rest of his career. In his 1992 book, Star Turns, Barry Took points out the embarrassment with sexual matters and his father’s position as appliance fitter as the root of the deep-rooted, insecure fear of copulation that prevented Benny’s humour from escaping a nudging, giggling world of childish smut. In my opinion, Hill knew exactly what the score was, playing to his youthful audience, getting the required reaction, and sticking with it.

While his father may have been the dictatorial master of the household, Hill’s mother was open and affectionate, happy to protect her 5-year-old son’s female flirtations at Shirley Infant School, Wilton Road, and eager to discuss at length bodily functions of all kinds. It was hardly a sheltered upbringing, and before long Benny was cracking the first of many risqué treasures:

Teacher: ‘Where have you been?’’

Late Boy: ‘Up Shirley Hill.’

Teacher: ‘Who are you?’

Late Girl: ‘I’m Shirley Hill.’

Just the kind of thing to get the other boys to stop hitting you in the dinner break, this little story was given added credibility as Shirley Hill was a local beauty spot.

Painful experiences that shaped Hill’s comedy include tales of a brief clash with a child molester, dreadful parental rows at home, bereavement (his mother’s parents, Gran and Granpa Sims, died in 1929 and 1930 respectively) and deeply hurtful female rejections, but the star himself would often relate happier times with his father, skipping along to his shop in Market Street with his lunch and playing the Jewish card game Kiobbiyos – which his father would as often as not let him win. However, this myth of an idyllic childhood served the public persona of a star remembering his dead father, as in a 1983 TV Times interview by Jennifer Farley, headed ‘The Clown who Made his Old Dad Very Happy’ (12–18 March), whereas privately, he often confided to his equally embittered brother that he could have cheerfully killed his father!

The power of his father was vitally important to Benny Hill – reflected comically in his stupid, aged, misunderstanding comic sketch parents, and in his fearful respect of police, doctors, lawyers and every other authority figure – but the spectre of female rejection remained the overwhelming aspect of his comic expression, although he had no fear of women, simply respect, and there was no shortage of female playmates and hand-holding in the early years. Aged 5, he would playfully frolic with little Peggy Bell, but later the usual teenage angst led to depressions, nail-biting and long walks.

At the age of 12, Hill discovered his ideal woman. In September 1936, he was staying with his cousin in nearby Eastleigh for Carnival Week when a vision of dark-haired loveliness with a green coat caught his imagination. The crush was, he explained in later years, ‘the biggest I’ve ever had’, and on his return home he would walk six miles just to get a glimpse of her. Four years later, 16, streetwise and much more confident, Hill saw her again, asked her to the pictures, but felt ‘no sparks’ on their date, and called it a day. Now, whether this mysterious young lady is Citizen Hill’s Rosebud is debatable, but the repeated impetuous proposals that marked his life have their roots here. Gallant, caring and kind to women throughout his life, the victim of his humour was always the man – and more importantly, himself, his younger, love-struck 12-year-old self from Southampton adolescence. Therapy, inspiration or self-mockery, Hill the comedian continually used this inner catalogue of emotions to fashion a universal language of classic television comedy.

Coming from a family of frustrated performers and acting the schoolroom clown through necessity and enjoyment, his early years were spent transfixed by cinema. Allegedly, by the age of 3 he had already perfected the staggering walk of Charlie Chaplin! And it wasn’t just the magical movies inside – Hill was fascinated by the cinema building itself, spending many happy childhood days riding his bicycle to new picture palaces just to check out the elaborate decor. But those glorious stories from his mother gave him a love for language, even though his party piece, a ballad concerning Mustapha and Hussan, was hardly his best use of it. Word games with brother Leonard and a shared delight in the world of Damon Runyon pointed him in the right direction.

Hill delighted in entertaining his friends and family, discovering a gift for impersonating everyone from Louis Armstrong to Jack Buchanan, which became his main obsession at the time. BBC radio voices of Max Miller and Robb Wilton delighted him, he perfected the unique vocal delivery of George Bernard Shaw and H.G. Wells, while cinema provided the source for his first female impersonation, Mae West, and his first real character technique as Claude Rains, using a kitchen knife to create a set of false teeth from orange peel and painting on a moustache with his mother’s eyebrow pencil. Performances as sexy Maurice Chevalier, grouchy Edward G. Robinson and buoyant James Cagney, or comic monologues wearing his George Robey hat were all part of his childhood love of becoming somebody else to entertain people. Naturally, this talent would become an important part of his classic television shows, although, on reflection, his inspired performances as W.C. Fields, Peter Lorre and Max Miller himself are unfairly forgotten in light of the clichéd ‘dirty old man’ misunderstanding.

Another important but often underrated string to his performing bow was music, a skill also embraced while Hill was still at school. At an early age, he sang to the accompaniment of his father’s one-string violin, and later, he loved to play music himself, realizing its important place in the overall structure of a show. In later years, Hill would become proficient on guitar and cornet (once playing at a big concert with Ted Heath and His Orchestra), but during these formative days he supported himself by playing drums in a local band – a talent which united him with contemporary struggling comic genius Peter Sellers in nearby Portsmouth.

Always happy to reclaim milk round memories.

The young Hill delighted in sound, and one of his earliest party pieces was a sound-only ‘walk through the countryside’, complete with golf balls hitting animals and other surreal audio pictures. His position of family clown at the age of 9 or 10 even impressed his father, although he would usually walk out of the room to laugh rather than let his son see his appreciation of the performance. Father’s weekly trips to his Freemasons’ lodge would inspire Benny with a flurry of comic observation – sending up his father’s well kitted out attire with mini gangster kaleidoscopes, elongated James Cagney death scenes and George Raft coin-tossing or flamboyant orchestra situations with exaggerated conducting movements and mimed violin solos.

Around this time, Hill was briefly part of the choir of St Marks Church, but – typically – solely for the 6d a week fee and a trip to the Isle of Wight. By 1935, he had won a scholarship to the Richard Taunton School, but life there was just boring enough to allow him plenty of day-dreaming moments. Disinterest was reflected in his poor academic achievements at school, although art was a favourite subject, and the boy was good – his old teacher kept a statue from among Benny’s work and bequeathed it back to the star in his will, while actress Connie George bought a carving of an Aztec head by the talented 11-year-old. This artistic bent was pinpointed by a TV Times piece (‘A Dream in the Life of Benny Hill’, 25–31 May 1985) for which Hill posed for a Lord Patrick Lichfield photograph, typically depicting him with a glamorous model reflected in his abstract portrait, and equally typically, balanced by fond memories of his own saucy mind: he had peppered a school project entitled ‘The City of Dreadful Night’ with a montage of prostitutes and sailors looking for action.

School also gave him the chance to play goalkeeper for the football team – which allowed him to fill quiet spells with impromptu gorilla impressions from the crossbar – and to develop a profitable cottage industry removing 14 carot gold nibs from discarded pens and swapping them for gold coins, jewellery, and eventually, semi-precious gemstones. Hill enthralled his small audience with a three-dimensional boot-box peep-show depicting scenes from Treasure Island. He was also a dab hand at flicking his well-worn cigarette cards. Most importantly, school days presented him with his first real taste of theatrics. Apart from art, Hill loved his French lessons, but even more influential than these was English, with his guiding teacher Dr Horace King. Later to enjoy a hugely successful political career, become Speaker of the House of Commons and enjoy the title Lord Maybray-King, King spotted acting potential in his young pupil, encouraged his flamboyant comic expression, and vitally, cast him in his first scripted stage performance. Yes, Hill’s earliest official work was as a rabbit in a school production of Alice In Wonderland. Hardly the most taxing of beginnings, he had to wear a sign round his neck reading ‘Rabbit’, and found his dialogue consisted almost entirely of emitting the occasional squeak, although the role did showcase Hill’s first painful pun – crying out ‘’Ear! ’Ear!’ during the courtroom scene.

From the age of 13, Hill tried his hand as an amateur entertainer in and around Southampton, tuning his natural talent for impression, but overloading his act with the familiar sounds of Harry Roy, Horace Kenny, Claude Dampier and Stainless Steven, giving nothing more than a reheated, albeit impressive, presentation of each artists’ act.

In these days before the Second World War, BBC radio comedy was tightly guarded against smut and innuendo. Before armed conflict allowed Tommy Handley’s It’s That Man Again and Max Miller to become vital home front comforts, BBC Director General Lord John Reith deplored any hint of suggestive material, and Miller was banned from the BBC for allegedly cracking the joke about an optician whose client complained: ‘Every time I see F you see K’ (think about it). Miller found refuge on the less morally censored Radio Luxemburg, and of course, the variety theatres, which were packed for his every performance.

One of those faithful millions who warmed to the cheeky chappie’s irresistible charm was a certain Benny Hill, and without a doubt, no single comic was more influential on him. While eulogizing fans later placed Hill firmly in the tradition of Chaplin and Keaton, it is essential to highlight the influence of Max Miller, Donald McGill’s saucy seaside postcards and Brighton end-of-pier variety shows throughout his work. A fresh, streetwise, confident figure – in contrast to the hugely successful comic characterizations of, say, George Formby or Frank Randle – Miller embraced an air of American-styled fast banter while embodying the British spirit. It’s true that American comedians fascinated the young Hill during trips to the cinema, and as with Liverpool’s 1950s influx of pure rock ’n’ roll, Southampton was full of sailors arriving with the latest recordings from New York. As a result, Hill was brought up on a staple diet of Louis Armstrong, Fanny Brice, The Two Black Crows and Whispering Jack Smith, savoured on the family wind-up gramophone. However, it was Miller, ‘The King of the South of England’, who captivated the young Hill. Miller’s brightly coloured suit, blue and white books and jauntily angled trilby embodied the essence of fish ’n’ chips, kiss-me-quick hats and naughty weekends by the sea.

The serious face of war-stunning publicity pose for the 1959 filmLight Up The Sky!

Love is in the air... Benny turns on the romantics with Who Done It? co-star Belinda Lee.

The young hopeful...

When at the start of the Second World War he began to experiment with his own material, Hill embraced the cheeky innuendo of his idol. He couldn’t have hoped for a better role model. Hill’s father was less than impressed, introducing bike riding, swimming, boxing and thrilling trips to see American speedway ace Sprouts Elder as diverting distractions – with varying degrees of success – but the excitement of performance was all-consuming. Even Benny’s refereeing of his brother’s scrappy boxing bouts would resolve into a perfect ‘cocky cockney’ routine. Finally, several visits to the music hall culminated in a guided tour of the Southampton Hippodrome. The object of the exercise was to dampen the young man’s ambitions rather than fire his imagination, but predictably, he became even more stagestruck, so his father finally relented and bought him his first professional make-up box. Some sources claim that Hill made his official stage debut as early as the age of 9, with an appearance at Southampton’s Palace Theatre in 1933. Whatever the truth in that, Hill’s performing career really began to take off during the days immediately before the Second World War. His father was secretly impressed by Benny’s talent, and encouraged him with back-handed comments and half-hearted actions, but continually damped the boy’s aspirations with knowing asides that showbusiness was nothing like a Betty Grable picture. His son wasn’t really bothered. In the summer of 1938, he had seen Albert Hunter and the Jitterbugging Maniacs in The Cotton Club Revue at the London Palladium. As J. Worthington Foulfellow was about to sing, ‘It’s an actor’s life for me’, and the young Alfie was hooked.

THE STAGE

Despite the best intentions and best efforts of his father to dissuade him from a career on the stage, the natural clown was in Hill’s genes, he revelled in the buzz an appreciative audience’s laughter gave him, and the glamorous prospects were more than enough to attract a wide-eyed teenager. Along with his older brother, Leonard, Hill had run through his collection of vocal tricks – playing Crosby, Wilton, Durante, Buchanan and the Ritz Brothers in their double act depicting three different radio broadcasts: BBC programming, Radio Luxemburg and American commercial radio. The climax had Benny being bashed over the head with a gong – it was that sort of show. These performances were for charitable events for the Fellowships Supporters Council, but for Leonard, the future lay in teaching, eventually becoming a headmaster.

In 1938, at the age of 14, Hill landed his first semi-professional position with Bobbie’s Concert Party. His two spots were very short, and the deal was only struck because six performances were imminent and nobody else was available, but he relished the chance. Firstly, he would come on in woolly hat and heavy coat, toss a handful of shredded paper in the air to serve as a cheap snow effect, and chatter about the bad weather. A better characterization had him playing a vicar, wearing one of his dad’s collars back to front and made up with lipstick and rouge borrowed from his mother. Hill performed as ‘second comic’, and all the gags were stolen from various source material he had filed away. One-liners such as ‘The Young Mother’s Club seems to have a shortage of young mothers – in spite of all the efforts of myself and the Bishop’ were probably beyond the young comedian’s powers of delivery, but it was invaluable early experience – albeit short-lived, since after the six shows, his contribution was curtailed. However, he was learning the business. Offered the fee of 2s 6d or a bottle of pop and a taxi home, the young Benny took the money and walked!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Tausende von E-Books und Hörbücher

Ihre Zahl wächst ständig und Sie haben eine Fixpreisgarantie.

Sie haben über uns geschrieben: