7,19 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Allison & Busby

- Kategorie: Krimi

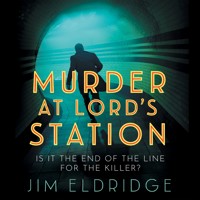

- Serie: London Underground Station Mysteries

- Sprache: Englisch

Christmas, 1940. A temporary truce between the German and Allied forces is a welcome respite from the relentless air raids over London. Down Street underground station, in the heart of Mayfair, is now a secret retreat for Prime Minister Winston Churchill and his cabinet. In this supposedly secure location, the body of a woman is found, stabbed in the heart. Detective Chief Inspector Coburg and Sergeant Lampson are called to investigate. However, whispers of treason as well as the suspicion of insidious Russian plots muddy the waters of the case, and personal resentments strike far too close to home. Everything is on the line for Coburg and Lampson as the body count steadily rises.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 405

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Ähnliche

5

MURDER AT DOWN STREET STATION

JIM ELDRIDGE

To my wife, Lynne, who has been my rock and my support for so many years.

CONTENTS

CHAPTER ONE

Wednesday 25th December 1940

Detective Chief Inspector the Right Honourable Edgar Saxe-Coburg and his wife, Rosa, known to the public as the jazz singer Rosa Weeks, raised their glasses of red wine and toasted one another across the dining table.

‘Happy Christmas,’ said Coburg.

‘At least for one day,’ said Rosa. ‘Do you think they might extend the truce?’

A truce for Christmas Day had been agreed between Berlin and London. After three months of constant bombing, mainly at night, the skies above London were clear of enemy planes. Most people had spent Christmas Eve in their deep shelters, which for Coburg and Rosa meant the air raid shelter in the basement of their small block of flats in Piccadilly, while most Londoners had sought refuge on the platforms of the capital’s Underground stations. For all of them sleep had been difficult to achieve with the heavy bombing pounding the city, the vibrations felt deep below ground, making everyone worry that at any moment the shelter may collapse and tumble down on them, along with thousands of tons and earth and bricks and rubble from the buildings above them. And then, almost as if someone had thrown a switch, at midnight the pounding ceased. There had been talk of a truce between the two warring nations, Britain and Germany, but most people had been sceptical. ‘You can’t trust Hitler,’ was the phrase on most people’s lips, with the word ‘Blitzmas’ being used to describe this festive season. The year before, 1939, Christmas had been normal, despite war having been declared at the start of September: festivities, parties, presents, carol singers in the streets, Christmas lights, turkey with all the trimmings for Christmas dinner, followed by Christmas pudding. This year there were no Christmas lights, no carol singers, the blackout was strictly enforced and rationing had meant no turkey for Christmas dinner. Instead, it was very small portions of lamb or mutton or – if you knew a butcher who had some – rabbit. With no dried fruit available, Christmas pudding was made from carrots.

Most people had refused to believe there really was a truce and had remained in their Underground station shelters rather than risk coming out. After all, it was now after midnight; the streets were completely dark due to the blackout and torches were forbidden and there was always the risk of someone falling into a bomb crater in the darkness. But as dawn came and still no more bombs fell, gradually people emerged from the shelters and made their way home.

Coburg and Rosa opted to leave their underground shelter at half past midnight and made their way up the stairs to their flat by the light of a torch, deciding to risk it, although it took a while for them both to get to sleep.

When they woke on Christmas morning they listened to the wireless for a while, the news to get confirmation that the Christmas Day truce was still holding, then music, while they made breakfast of toast. They’d decided to leave opening their Christmas presents until they sat down for Christmas dinner, so the morning was spent telephoning Rosa’s parents in Edinburgh to wish them happy Christmas, then Edgar’s elder brother, Magnus, the Earl of Dawlish at Dawlish Hall, before they settled down to prepare the Christmas dinner together: roast mutton, roast potatoes with cabbage and carrots. The meal eaten, they each handed the other the presents they’d bought, wrapped in thin brown paper because restrictions meant there was no actual Christmas wrapping paper available. Rosa had bought Coburg a diary for 1941, and Coburg had bought Rosa a bath set with special scented soaps.

‘This is fantastic!’ exclaimed Rosa as she undid the wrapping. ‘Exactly what I was hoping for. They said in the papers that soap was in such short supply, anyone hoping to receive it as a present was going to be unlucky. How did you manage to get this?’

‘The Eton network.’ Coburg smiled. ‘An old school chum of mine is married to a woman who’s someone important in a big cosmetics company.’ He looked down at his empty plate and said, ‘I’m feeling guilty. It’s Christmas Day. I should have taken you to The Savoy or The Ritz or somewhere for Christmas dinner. Or we should have made the trip to Dawlish Hall. Magnus and Malcolm will be sitting down to roast chicken with all the trimmings with a spread by Mrs Hilton that will have nothing spared. It’s one of the advantages of living in the country. Fresh eggs, bacon, vegetables. We could have driven there on Christmas Eve late afternoon after I’d finished work and then come back this afternoon.’

‘No,’ said Rosa. ‘I wanted our first Christmas together to be just us, here at our own home. But, if there really is a truce in place, we can go out for a walk this afternoon.’

‘Putney,’ proposed Coburg. ‘A peaceful stroll along the river before midnight comes and we’re once again under the bombers.’ He grinned. ‘Or, before that, we could return to our bed and take advantage of an absence of air raids to disturb us.’

Rosa got up and took his hand.

‘This is what I call a perfect Christmas.’ She smiled as she led him towards the bedroom.

Deep below ground at the Down Street Headquarters of the Railway Executive Committee in the disused Underground station, Edward Pennington walked through the empty offices towards the small section of railway platform that had been added on when the former Underground station had been reallocated. As a senior officer of the REC, Pennington was able to flag down a passing train to get to the next station on the Piccadilly line for onward travel. He was glad to be finishing his twelve-hour shift and get home. Not that Christmas Day held any special meaning for him. He was a bachelor, so there was no young family that needed him at home to entertain them, nor a wife to share the day with, just his very elderly, housebound mother waiting for him so that she could moan to him about their neighbours. Pennington had always found the neighbours on both sides to be amenable, not unduly noisy, polite whenever he passed them in the street, but his mother was convinced they were doing their best to make her life a misery.

‘They make faces at me as they pass our window,’ she complained to him. ‘You ought to report them to the police. They could be German agents.’

In vain he had tried to reason with her that none of their neighbours were Germans, nor were they sympathetic to the Nazi cause, but she resolutely refused to be convinced. If only I had a sister, or Mother had relatives, who could take her in, thought Pennington.

He passed through the outer office into the smaller one with the door that would take him out onto the small railway platform. He stopped beside the door marked ‘Access To Track’ and pressed the red switch on the wall, before opening the door and stepping out onto the platform. The blue light requesting the next train to stop was now alight, and in its blue haze he could see what looked like a bundle of rags lying on the platform by the edge.

For Heaven’s sake, he thought, outraged. Who’s dumped their rubbish here? One of the train drivers, he supposed.

He stopped by the pile of rags and prodded it with the toe of his shoe, and was surprised to strike something solid. Curious, he peeled a piece of cloth back, and was shocked to uncover a woman’s white face. He saw at once that she was dead; he’d seen enough dead people since this war had started to recognise death.

He turned and ran back to the door and into the office. Once inside he pressed the red switch to turn off the blue light, then hurried to the telephone and dialled 999.

‘Police,’ he said urgently when the operator answered. ‘There’s a dead woman here at Down Street.’

CHAPTER TWO

Thursday 26th December 1940

Coburg pulled the police car in to the kerb outside Ted Lampson’s terraced house in Somers Town and slid across to the passenger seat to let his detective sergeant get behind the wheel. Lampson loved cars, but couldn’t afford one of his own. The journeys he and Coburg made gave him a rare opportunity to drive, sharing driving duties as they did.

‘How was your Christmas, guv?’ asked Lampson as he put the car in gear and made for Scotland Yard.

‘Excellent,’ said Coburg. ‘How was yours? Did Terry have a good day?’

‘He did,’ said Lampson. Terry was Lampson’s ten-year-old son, who Lampson, a widower, was bringing up on his own with the help of his elderly parents. ‘Me and my dad took him to White Hart Lane.’ He gave a broad grin. ‘We thrashed Everton. Good old Spurs!’

‘It’s a strange day to have football matches,’ mused Coburg. ‘Christmas Day.’

‘It’s traditional,’ said Lampson.

‘But with so many teams having players away in the services, I don’t see how some of them can field a team.’

‘Well, that’s true,’ said Lampson. ‘Did you hear about Brighton and Hove Albion?’

‘No,’ said Coburg.

‘They played Norwich, but Brighton only had five players, so they had to cobble together a team from the crowd who were watching.’

‘Spectators?’

Lampson nodded. ‘It was a brave effort, but hardly worth it.’ He chuckled. ‘Norwich won eighteen–nil.’ Then, thoughtful, he added, ‘It seems strange going to work on a Boxing Day. I know we used to do it if we drew that kind of shift, but everyone’s going back to work today. It don’t seem like Christmas.’

‘It isn’t,’ said Coburg. ‘This year was a one-day Christmas. They need to get the munitions factories back to work.’

‘Still, at least we were spared the bombing for a day. Pity they can’t make it longer.’

‘It will be once one side wins the war.’

‘You mean when we win the war,’ Lampson rebuked him.

‘Of course,’ said Coburg smoothly. ‘The alternative is unthinkable.’

When they arrived at Scotland Yard, they found Superintendent Allison in their office, writing a note.

‘Ah, good,’ he greeted them. ‘I was just about to leave a note for you.’ He screwed up the piece of paper and threw it in the wastepaper basket. ‘There was a murder yesterday at Down Street Underground station. Or, rather, what used to be the Underground station. It was picked up by Inspector Best, who was on duty on Christmas Day, but unfortunately he was injured last night when a building damaged by bombing collapsed near him.’

‘Was he badly hurt?’

‘A broken leg, which will put him out of action. He’s in hospital and is likely to remain there for a few weeks, at least. It was a bad break. I’d like you to take over the case. You’ve had recent experience of dealing with a dead body found on the Underground, and, like that one, the victim was found at a Tube station that’s been discontinued from active passenger traffic. Although trains still pass through it.’

‘Did you say Down Street?’ asked Coburg.

‘I did,’ said Allison.

‘That’s the one that the Prime Minister’s currently using as an underground bunker, I believe.’

‘You believe right. Which is another reason I’d like you to take on the case. I understand your elder brother, the Earl of Dawlish, is an old friend of Churchill’s.’

‘Yes, sir, he is.’

‘Which might help if there are complications concerning national security. The former station’s been converted into the headquarters of the Railway Executive Committee, the outfit set up to run the country’s railways.’

‘Where was the body found?’

‘On a stretch of platform there.’

‘Does it still have a platform? I thought it had been abandoned as a working station.’

‘Inspector Best will have the details. I’m sure he’ll be able to answer all your questions.’

‘Where is he?’

‘At University College Hospital. I’ve telephoned ahead to alert them that you’ll be coming in to see him so you shouldn’t meet with any of the usual problems about calling on patients out of visiting hours.’ He picked up a cardboard file from the desk. ‘I brought this along for you. It’s the file Inspector Best opened on the case before he was injured. There’s not much there, but I’m sure he’ll be able to fill you in.’

As Lampson drove them to University College Hospital, Coburg read through what little information there was in the slim file. The fact there was so little was understandable; Richard Best had only just caught the case and had little time to make any notes from his visit to the scene to look at the body, before he’d been injured.

‘The victim was a woman in her twenties called Svetlana Rostova,’ Coburg told Lampson. ‘She’d been stabbed. She was a fortune-teller, known as Lady Za Za.’

‘I guess she didn’t see this coming,’ commented Lampson wryly.

The bed Inspector Richard Best was in at UCH had a canopy erected at the foot of it to protect his broken leg. Best was in his fifties and Coburg and Lampson found him leaning back against his pillows and obviously in pain.

‘You’ll have to forgive me if I drop off to sleep while we’re talking,’ he grumbled. ‘They’ve pumped all this morphine into me to ease the pain but it makes me keep nodding off.’

‘We won’t keep you long,’ promised Coburg. ‘How are they treating you in here?’

‘The same way they treat everyone,’ Best said with a scowl. ‘They’re officious and the ward sister is a right tyrant. And don’t get me started on the matron. Awful woman. I’m sure she’s got a moustache. It wouldn’t surprise me to find she’s a draft-dodger posing as a matron.’

Coburg settled himself down on the chair beside the inspector’s bed and opened the file.

‘I’ve read your report,’ he said.

‘That must have taken you all of two minutes,’ said Best. ‘I’d jotted down a few notes then left the office intending to enlarge on it today. Instead of which, this bloody building came down as I was walking past it.’

‘It could have been worse,’ said Coburg sympathetically. ‘You could have been killed.’

Best scowled.

‘Don’t worry, this place’ll finish me off,’ he grumbled. ‘I thought nurses were supposed to be all lovey-dovey and caring.’

‘The ones I’ve experienced have been,’ said Coburg.

‘You were lucky,’ grunted Best. ‘I reckon this lot were trained by the Gestapo. So, what can I tell you?’

‘The body was found on a platform.’

‘That’s right,’ confirmed Best.

‘By a man called Edward Pennington who went out on the platform to catch a train home after his shift had ended.’

Best nodded.

‘As I understand it, his shift had ended and another man had arrived to take over.’

‘Right again,’ said Best.

‘Why didn’t this other man spot the body when he arrived?’

‘Because it was on a different platform,’ said Best. ‘I’m guessing you haven’t been to Down Street since it got rebuilt.’

‘No,’ said Coburg.

‘A platform was added so the senior staff could grab a train to get home, or go somewhere. There are two platforms on opposing sides of the railway tracks: westbound and eastbound. Pennington was leaving on the eastbound platform. The bloke who took over from him arrived on the other platform, the westbound.’

‘Have you spoken to the other man?’

‘No. I didn’t even get a chance to get his name. They’re pretty tight-lipped there, think they’re some kind of secret service. Bunch of petty bureaucrats.’

‘Where was the body taken?’

‘Here,’ said Best. ‘UCH. Dr Welbourne was the attending medic.’

‘Yes, we know Dr Welbourne,’ said Coburg. ‘A good bloke.’

‘I don’t know him well enough to say,’ said Best. ‘He seemed alright.’

‘Is there anything else you can tell us?’ asked Coburg.

‘No. Like I say, I was intending to start on it properly today, but that bloody house falling on me put a stop to that.’

‘Did she have any next of kin?’

‘No idea,’ said Best. ‘That was another thing I was going to look into. She was Russian.’

‘Yes, I gathered that by her name,’ said Coburg.

‘According to her ID card she came here in 1937. I went to the address on her card, which was a house of rooms for rent, but the landlady said she’d left there two weeks before and left no forwarding address. That was as far as I got before I copped this.’

Coburg and Lampson left Best and made their way down to the mortuary in search of Dr Welbourne.

‘Well, there’s one bloke whose Christmas was ruined,’ sighed Lampson.

‘Have you had much to do with Inspector Best before?’ asked Coburg.

‘No,’ said Lampson. ‘I’ve heard about him. People say he’s a miserable sod.’

‘Yes, I’d agree with that.’ Coburg smiled.

‘I thought he was in that mood because he broke his leg,’ said Lampson.

‘No, he’s always like that,’ said Coburg.

‘Has he got family?’ asked Lampson.

‘He had, but his wife divorced him and took the kids back up north. She said living with him was making her life a misery.’

‘Well, he’s certainly got a negative view of things. Like nurses, for example. That time I was stabbed and at death’s door they were brilliant.’

They found Dr Welbourne just finishing an autopsy on a dead man.

‘Just give me a minute or so while I sew this one up,’ he said.

‘We’ll wait outside,’ said Coburg, and he and Lampson left Welbourne energetically sewing up a long incision he’d made from the dead man’s chest down to his abdomen.

‘I don’t know how he can do that,’ groaned Lampson. ‘Every day, blood and guts, taking out brains and examining them.’

‘It’s not much different to what we do when we examine a murder victim,’ said Coburg.

‘Yeah, but we only look at their outside. We don’t take them to pieces.’

It was another ten minutes before Welbourne came out of the mortuary, wiping his hands on a towel.

‘Good morning,’ he greeted them cheerfully. ‘To what do I owe the pleasure?’

‘We’ve been assigned the murder of Svetlana Rostova,’ said Coburg.

‘Why, what’s happened to Inspector Best?’

‘He broke his leg last night. He’s currently occupying one of your hospital beds upstairs.’

‘Good heavens! What happened to him?’

‘A building that had been bombed fell on him.’

‘In that case he was lucky to escape with just a broken leg. And he’s in here, you say, at UCH?’

‘Yes. I’m surprised no one told you.’

‘There was no need. He’s alive; I only get informed about the dead.’

‘So, what can you tell us about Svetlana Rostova, who we’re told also worked as a fortune-teller under the name of Lady Za Za?’

Welbourne gestured towards the doors to the mortuary. ‘If you come through I can show you her body, and the possessions she was found with.’

Coburg and Lampson followed Welbourne into the mortuary and he took them to a table where a body lay covered with a sheet. He peeled the sheet off, exposing the naked body of a young woman in her twenties. She was thin, and had been attractive with her high Slavic cheekbones and her jet-black hair. Her body was scarred with large stitches where Welbourne had opened her up to take out her internal organs for examination, and then sewn her up again.

Welbourne pointed to the wound just below her left breast. ‘Stabbed,’ he said. ‘A thin, long-bladed weapon, something similar to a stiletto. Very neat. One thrust straight into the heart. Either the killer knew enough anatomy to avoid the ribs, or they were lucky.’

‘Time of death?’ asked Coburg.

‘From the contents of her stomach I’d say some time between four o’clock and six o’clock yesterday.’ He looked down at her ruefully. ‘Not the best way to spend Christmas Day, getting murdered.’

‘Did you talk to anyone at Down Street yesterday?’

‘The person who found her body, a man called Edward Pennington. He was supposed to leave as his shift was over, but he felt it his duty to wait until I arrived.’

‘Her body was found on a small platform there, we understand.’

‘Yes, that’s right. Have you been to Down Street?’

‘Not yet, we thought we’d come and see you first to get as much information as we could before we talked to them. I got the impression from Inspector Best that the people at Down Street might be difficult. He described them as tight-lipped, petty bureaucrats.’

‘I’m afraid Inspector Best can be quite an abrasive person.’ Welbourne smiled. ‘I think your calmer, friendlier approach might prove more effective in this case.’ He replaced the sheet over Svetlana’s dead body, then took them to a large open cupboard containing a series of drawers. He pulled one of the drawers out and put it on a table. It contained clothes, a handbag and an official visitor’s pass on a lanyard. ‘These are what were found on her.’

Coburg opened the handbag and took out the contents. There were cosmetics, lipstick and face powder, and her ID card. It bore the word ‘alien’ above her name. In the section ‘nationality’ it said ‘Russian’, and ‘date of arrival’ read ‘January 1937’.

‘Can I take this?’ asked Coburg, holding the ID card. ‘I’ll give you a receipt for it.’

‘Of course,’ said Welbourne.

‘Can you make out a receipt for Dr Welbourne, Sergeant?’ asked Coburg.

Lampson nodded and produced a dog-eared receipt book from his inside pocket, and proceeded to fill in one of the slips; while Coburg turned his attention to the visitor’s pass, which bore the stamp of the Railway Executive Committee.

‘It seems that she was at Down Street officially,’ he said.

‘Well, this Edward Pennington didn’t seem to know her,’ said Welbourne. ‘Nor did anyone else. Mind, it was a skeleton staff yesterday, being Christmas Day. I assume you want to take that with you as well.’

‘Yes please,’ said Coburg. ‘Hopefully it will help us find out what she was doing at Down Street.’ He handed the pass to Lampson. ‘And another receipt for this, please, Sergeant.’

CHAPTER THREE

As Rosa and Doris brought their ambulance in through the gates of the Paddington St John Ambulance station, they saw their boss, Chesney Warren, standing by the door to the building, waving to them to hurry.

‘Something’s happened,’ said Doris, concerned.

They’d just returned to the station from delivering a woman with a suspected burst appendix to the nearest hospital. Rosa stopped the ambulance beside Warren and Doris wound her window down.

‘What is it and where is it?’ she asked, reaching out for the usual piece of paper.

‘Neither,’ said Warren. ‘It’s the BBC on the phone for Rosa.’

‘For me?’ said Rosa in surprise.

‘Yes. I saw you coming in as I picked the phone up and this chap said, “Excuse me, would it be possible to speak to Rosa Weeks? I’m calling from the BBC.” Very posh-sounding.’

‘How did he get this number?’ asked Rosa.

‘I’ve no idea,’ said Warren, ‘but the fact he did suggests he definitely wants to talk to you.’

Rosa got down from the cab and hurried into the building and Chesney Warren’s office, Warren following her. She picked up the receiver and said, ‘This is Rosa Weeks.’

‘I’m very sorry to trouble you at work, Miss Weeks,’ said a cultured but very gentle man’s voice. ‘My name’s John Fawcett and I’m the producer of Henry Hall’s Guest Night on the BBC Light Programme. I know this is very short notice but I wonder if you might be free next Tuesday, the 31st December, New Year’s Eve, and if you might consider appearing on the show.’

Rosa was momentarily stunned into silence, then she said, doing her best to keep her voice controlled, ‘Yes, I would. Thank you.’

‘It is a live broadcast,’ said Fawcett. ‘Next Tuesday we’ll be at the Finsbury Park Empire. The show is broadcast from 6 p.m., but you’d be needed for rehearsals that afternoon, from one o’clock, if that would be convenient for you.’

‘Yes, indeed, that would be convenient.’ She looked at the intrigued Chesney Warren and mouthed, ‘I’ll tell you in a moment,’ as Fawcett said, ‘That is absolutely wonderful, Miss Weeks. Can we meet to discuss your slot on the programme?’

‘Of course. When do you suggest?’

‘Can you be free for lunch tomorrow? The BBC canteen does reasonable fare.’

‘Yes.’

‘Excellent. It’ll have to be at the Maida Vale studios in Delaware Road. We’ve got a few problems at Broadcasting House. Bomb damage, I’m afraid. Do you know Maida Vale?’

‘Yes,’ said Rosa.

‘Very good. I’ll see you there. Will one o’clock suit you?’

‘One o’clock will be fine.’

Rosa replaced the receiver and looked at Chesney Warren, stunned.

‘That was the BBC,’ she said.

‘I know,’ said Warren. ‘I was the one who told you. What did they want?’

‘They want me to appear on Henry Hall’s Guest Night next Tuesday, live from the Finsbury Park Empire.’ Apologetically, she added, ‘He asked me if I would, and also if I’d meet him for lunch tomorrow to discuss my spot, and I said yes without asking you. I’m very sorry.’

‘Nonsense,’ said Chesney. ‘No apology needed. D’you think you’ll be able to get a mention about the St John Ambulance and that you’re a volunteer driver?’

‘I can certainly ask,’ said Rosa. ‘With a war on they might be pleased to tell the audience that.’

Or they might get upset with me for daring to ask and drop me, thought Rosa. However, John Fawcett had sounded the sort of kind man you could ask things without him taking offence. And it wasn’t as if she was demanding something for herself.

The exterior of Down Street had been kept intact despite its closure as a working Underground station; the three-arched semi-circular window above the entrance, the familiar coloured tiles in general use across the London Underground system were fixed to the walls as décor, and above the arch on the right that led to a rear courtyard a sign still read ‘Down Street’. Coburg and Lampson went to the black door to the left and rang the bell. A disembodied voice came from the grille on the right asking what they wanted.

‘DCI Coburg and DS Lampson from Scotland Yard,’ Coburg said to the speaker. ‘We’re here to investigate the recent murder here.’

‘One moment,’ said the voice.

There was a pause, then the door opened and a man in the uniform of London Underground’s railway police looked out at them. Coburg and Lampson showed him their warrant cards, and were admitted.

‘I’ll take you down to see Mr Purslake,’ said the officer.

They followed the uniformed officer to the head of a circular staircase and then down the winding stairs to deep underground. As they descended, they passed different places where there were exit points from the staircase going off into long corridors. It was at one of these exit points that the uniformed officer stopped. A man in a very smart clerical dark grey suit and bow tie was standing waiting for them.

‘The gentlemen from Scotland Yard, Mr Purslake,’ said the officer.

‘Thank you, Wilkins,’ said Purslake. ‘I’ll take over from here.’

The uniformed officer headed back up the stairs, and Purslake held out his hand in greeting to the two policemen.

‘Jeremy Purslake,’ he announced, shaking their hands. Coburg and Lampson introduced themselves to Purslake, who led the way further down the winding staircase.

‘It’s very deep,’ he said, ‘which is why it was chosen.’

‘No lift?’ asked Coburg.

‘There is a two-person lift, but it’s usually kept for senior personnel in case of emergency. I prefer to use the stairs.’ He gave them an unhappy look. ‘This is all most unpleasant. We’ve never had anything like that here before.’

‘How long have you been here?’ asked Coburg.

‘Since last year.’

‘I thought the station had been closed long before that,’ said Coburg.

‘It had,’ said Purslake. ‘Down Street opened as a station in 1907 and closed in 1932.’

‘Why did it close?’

‘Too few passengers were using it. We believe because, as it was in an affluent area, most of the local residents didn’t use public transport but preferred cars and taxis. The other problem was its close proximity to other Tube stations, Green Park, which was originally called Dover Street, and Hyde Park Corner.

‘Once it closed as a working station for passengers in 1932, the tracks were altered and the platform tunnels rebuilt to allow a junction to be installed with access from both the eastbound and westbound services to a new siding located between Down Street and Hyde Park Corner. The siding was mainly for westbound trains to reverse into it, but there was enough space for it to be used for servicing the trains. A small foot tunnel was built from the western end of the siding to Hyde Park Corner station. The lifts were taken out and the lift shafts adapted to provide additional ventilation.

‘Early in 1939 the station was chosen as an underground bunker for the use of the government in the event of war. The station’s great depth means it will be safe against bombing. Brick walls were constructed at the edges of the platforms, and the enclosed platform areas, along with the spaces in the passages, were divided up into offices, meeting rooms and dormitories.

‘The small two-person lift I mentioned earlier was installed in the original emergency stairwell and a telephone exchange and bathrooms were added. It was intended that the Railway Executive Committee would be the sole occupants and from here we’d be able to ensure the trains across the country would keep running. That’s why having the switchboard based at the deepest point is so essential: there will always be telephone connections to everywhere on the rail network. Previously the Railway Executive Committee had been based at Fielden House in Westminster, but the basement there was unsuitable. It wouldn’t have been able to withstand heavy bombing.’

They had now reached the lowest level and Purslake led them along a short section of tunnel to an office. Inside the office, ten people were hard at work at desks, some on telephones, some typing, some sorting through reports. The workers gave the visitors brief glances, then returned to their tasks.

At that moment there was the loud rush of a train hurtling past and the wall vibrating. Lights from the passing train flickered in a metal grille set high in the wall for ventilation.

‘As you see trains still pass along this line, the Piccadilly, and very close to the walls that were put up at the edge of the platforms. It’s something we just have to put up with.’

‘And this short platform that was added during the rebuilding is where the woman’s body was found?’

‘Yes. It’s a mystery where she came from. There’s no evidence that she came from inside the building, so we believe she was thrown from a passing train.’

‘But the doors can’t open when the train is moving,’ said Coburg.

‘That’s generally true,’ agreed Purslake. ‘But it is possible. The other option is that her body had been placed on the roof of a carriage and it fell off as it passed here.’

‘Can we see where her body was found?’

Purslake took them through the large office, then out of a door at the far wall and into an adjoining one. This one was smaller, and empty of people, with two desks, a telephone and filing cabinets. A door set in the wall that had been built at the platform’s edge had a large sign on it that said: ‘CAUTION. ACCESS TO TRACK.’ There was a large red switch beside the door.

‘That red switch operates a blue light in the tunnel,’ said Purslake. ‘When a driver sees that blue light is on, he pulls up beside the door and whoever is waiting on the platform gets on the train.’

‘May we see it in operation?’ asked Coburg.

Purslake nodded. He flicked the red switch, then opened the door and stepped out onto a short section of enclosed platform that had been constructed, Coburg and Lampson following. The tunnel was illuminated with the dull glow of overhead lighting, and also by a blue light from a lamp situated near to where they stood. Purslake pulled the door shut behind them. ‘We have to keep it shut otherwise it creates a terrible draught inside the offices.’

Directly opposite, on the other side of the railway tracks, was an identical short platform, also with a lamp – currently not glowing – set in the wall.

‘This side is the eastbound track. That platform is for the westbound one,’ Purslake explained.

They stood there on the short section of platform for about four minutes, and then Coburg heard the sound of a Tube train approaching and saw the glow of its lights as it drew nearer, then heard the sound of its brakes being applied. The train drew to a halt with a screech and a judder, bringing the driver’s cab level to where they were standing. The driver opened the door and looked at them questioningly.

‘Thank you, driver,’ said Purslake. ‘But we won’t be travelling at this time. This is Detective Chief Inspector Coburg from Scotland Yard, who’s making an examination of our systems.’

The driver nodded, pulled his cab door shut, then set the train in motion again. The noise as it raced past them was deafening and the rush of air seemed to suck them forward towards the train lines. Coburg and Lampson noticed that Purslake had stepped back and was by the door, as far away as he could get from the edge of the platform, and they decided to join him.

When the train had disappeared, Purslake opened the door and they went back into the small room. Purslake flicked the switch and checked that the blue light had vanished before closing the door.

‘The door’s not locked?’ Coburg observed.

‘No. If someone arrived on the platform to get to us, they would be able to get in.’

‘So there’s always access between the railway tracks and these offices?’

‘Yes.’ Purslake nodded. ‘Twenty-four hours a day. These premises have to be operational the whole time. We have a staff of forty working in two twelve-hour shifts.’

‘I understand that the Prime Minister is also based here,’ said Coburg.

‘Temporarily,’ said Purslake. ‘His office and facilities are on the next level up. He’s staying here while the Cabinet War Rooms are being renovated.’

‘Renovated?’ asked Coburg. ‘I thought they were already operational.’

‘They were, but they decided the War Rooms needed reinforcing to protect against the heavy bombing, so they began to put in extra layers of concrete. Since late October this has been effectively the Prime Minister’s underground bunker.’

‘So he’s here at the moment?’

‘His staff are,’ said Purslake. ‘A smaller staff than he has at the Cabinet War Rooms, but large enough for his needs. He’s mainly here at nights. His sleeping accommodation, dining, bathroom and toilet facilities are in a corridor that had already been converted into rooms. His secretaries and key staff members also have room in the same corridor.’

‘Do you often see him?’

‘Now and then, if he’s bored and feeling trapped in that one corridor, he’ll come down here to see how the trains are running.’

‘The dead woman was wearing a visitor’s pass,’ said Coburg. He took the pass from his pocket and handed it to Purslake. ‘Do you know who authorised it?’

Purslake took the pass and studied it. ‘Svetlana Rostova,’ he murmured. He went to one of the desks and took a ledger from the drawer. On the front was label with the words ‘Visitor Passes’. He looked at the number on the pass, then opened the ledger and ran his eye down the list until he found the number.

‘It was authorised by Grigor Rostov.’ He ran his finger along the entry and said, ‘He’s in the accounts department.’

‘Can we see him?’

Purslake picked up the telephone and dialled a number. When it was answered, he said, ‘Purslake here. I need to speak to Grigor Rostov. Can you ask him to report to me by the platform office.’ He frowned on hearing the reply, then replaced the receiver. ‘It seems he’s not in today,’ he told the detectives. ‘He telephoned in ill, saying he suffered food poisoning as a result of something he ate.’

‘Whatever he had for Christmas dinner, I presume,’ said Coburg. ‘Do you have his address?’

‘Certainly,’ said Purslake, and he took another ledger from the drawer.

‘The fact they have the same surname indicates he’s related to the dead woman,’ said Coburg. ‘Russian women’s names end in an “a” added to the family name. If she was Rostova, he’d be Rostov. He’s Russian, I assume?’

‘I assume so also,’ said Purslake. ‘It’s not a common name among our staff. But whatever their relation is, I don’t know. Husband and wife, brother and sister. I’m afraid I don’t know Grigor Rostov personally.’

CHAPTER FOUR

The address they’d been given for Grigor Rostov was a small terraced house in a back street in Paddington. Coburg was just about to knock at the door, when it opened and a young woman pushing a pram looked at them in surprise.

‘Good morning,’ said Coburg. ‘We’re sorry to trouble you.’ He produced his warrant card and showed it to her. ‘I’m Detective Chief Inspector Coburg from Scotland Yard. This is Detective Sergeant Lampson. We’re looking for Grigor Rostov. Does he live here?’

‘Yes. I’m his wife,’ she said warily. ‘What do you want Grigor for?’

‘We need to ask him some questions about an incident that occurred yesterday at Down Street.’

‘Grigor was here all day yesterday,’ she said. ‘It was Christmas Day. Whatever it is, he can’t have anything to do with it.’

‘Nevertheless, we do need to talk to him,’ said Coburg.

The woman hesitated, then called, ‘Grigor!’

A young man in his twenties appeared from inside the house and walked towards them, but stopped in the passage when he saw the two men standing with his wife on the doorstep.

‘They’re police,’ she said. ‘From Scotland Yard.’

Grigor Rostov looked at them even more warily than his wife had done.

‘May we come in?’ asked Coburg.

Mrs Rostov turned to her husband and said, ‘I’m taking Mary for her walk. She needs the fresh air.’ Then she turned to the two policemen and asked, ‘Or do you want me?’

‘No thank you, Mrs Rostov. We just need to talk to your husband.’ He stepped aside so she could get out of the house. The young woman hesitated, then, with a last worried look at her husband, pushed the pram out into the street and walked off. Coburg and Lampson entered the house, and Rostov gestured for them to go into the front room. The three sat down, and Rostov looked at Coburg and Lampson with deep unhappiness.

‘I know why you are here,’ he said. ‘I had a telephone call last night.’

‘Svetlana Rostova,’ said Coburg.

Rostov nodded. ‘She was my sister.’

‘Who telephoned you?’

‘A colleague from work. They were on the late shift and they heard about this woman who’d been discovered dead there. Stabbed. They guessed she was related to me once they found out her name was Svetlana Rostova.’

‘Does your wife know?’

‘Priscilla?’ Rostov shook his head. ‘I told her it was someone from work telling me about things I’d need to know when I went to work today.’

‘But you didn’t go to work.’

‘No. I thought I’d be questioned. I couldn’t face it.’

‘So you phoned in and pretended you had food poisoning.’

‘I just said I had an upset stomach.’

‘Your wife wasn’t suspicious?’

‘She knows I suffer with my stomach,’ said Rostov. ‘I will tell Priscilla about Svetlana being killed. I will tell her that is why you came to see me today.’

‘Did you see your sister yesterday?’

‘No. I hadn’t seen her for more than a week.’

‘You authorised a visitor’s pass to Down Street for her.’

‘Yes. She was desperate for somewhere to be safe at night during the bombing.’

‘There are plenty of air raid shelters she could have gone to.’

Rostov gave a sad shake of his head. ‘Svetlana wouldn’t go down them. She had had this vision of herself dying in one. She wanted somewhere safer, deeper underground.’

‘The inspector who was first on the scene went to the address on her identity card and was told she no longer lived there. That she left two weeks previously.’

‘She did not leave. She was told to go by the woman who owned the house where she was lodging,’ said Rostov bitterly.

‘Do you know why?’

‘The woman who owned the house had taken against her. She didn’t like Svetlana using her room to have customers to tell their fortunes. She said if she’d known she was going to do that, she’d never have let her move in. She said it was against her religion.

‘Svetlana had nowhere to stay and she begged me to find her a safe place to spend the nights during the bombing. She’d had a vision that she’d die in an underground air raid shelter, so she was scared to go to the Underground station or the public shelters. I couldn’t let her stay with us at home – my wife doesn’t like her. Svetlana is – was – odd. She frightened people with her looking into the future.’

‘According to her ID card she arrived in England in 1937. I’m guessing you arrived at the same time?’

‘Yes. We came here together.’

‘Your English is excellent for someone who’s only been in England for three years or so,’ said Coburg.

‘In Russia I worked in the department that monitored British financial transactions.’

‘For the Soviet government?’

‘Yes.’

‘Why did you and your sister leave Russia?’

‘To escape the Terror.’

‘The Terror?’

‘Stalin’s Terror. If we’d stayed in Russia we would have been killed.’ He saw the enquiring expression on their faces, so he enlarged on what had made them flee their native country.

‘Between 1936 and 1938 about three quarters of a million Soviet officials were executed and more than a million sent to the labour camps. Stalin is paranoid, convinced that the people around him are plotting his downfall. Many of them were people who’d been with him during the revolution that had ended the reign of the tsars and brought in a communist government. Nearly all of the old Bolsheviks who’d been with him before 1918 were purged.’

‘Purged?’

‘Killed. Even Trotsky, who’d been an architect of the revolution, was expelled from Russia in 1929.’

‘He was killed a couple of months ago,’ said Coburg. ‘I saw it in the newspapers. In August, I think.’

Rostov nodded. ‘In Mexico. He was killed by one of Stalin’s secret assassins. He was just one of Stalin’s former comrades who suffered that fate. Zinoviev and Kamenev were others who were accused of plotting to overthrow Stalin. They were tortured to make them confess their alleged crimes, and then executed.

‘Several show trials were held in Moscow as an example to local courts throughout the country to show what was expected of them. The Trial of the Sixteen was the first one in December 1936.

‘Our father was a general in the Red Army, completely loyal to Russia, and when he realised what was happening, that key figures in the Soviet establishment were being rounded up, tortured to make them confess, then executed, and that their families were also being killed, he ordered Svetlana and me to leave the country in secret. He managed to get us smuggled out through Scandinavia and we made our way to England, which he said was the only place we would be safe. He ordered our mother to accompany us, but she refused to go, saying she agreed Svetlana and I should leave, but she would stay with him.

‘We managed to reach England in January 1937. That same month there was the second show trial in Moscow, the Trial of the Seventeen. Then, in June of that year came the Trial of the Red Army Generals, including our father. They were all executed. Our mother was shot as well.

‘Following that came the Great Purge of 1937. In this it was ironic that the prosecutors who conducted the cases against the generals were themselves arrested and tried and executed. Stalin got rid of everyone he suspected of plotting against him, which was virtually everyone. In the armed forces alone, thirty-four thousand officers were executed. The entire politburo and most of the central committee were killed. About two million people were killed during the Great Purge.

‘In addition to the official show trials, the NKVD, Stalin’s secret police, arrested and executed anyone suspected of opposing Stalin’s regime, and gossip alone was enough for a death sentence. By the NKVD’s own account, seven hundred thousand people were shot during 1937 and 1938 alone.

‘With that kind of background, I hope you can understand why Svetlana became, as they say, odd.’

‘Who do you think might have a reason to harm your sister?’

‘Stalin,’ replied Rostov.

‘But he’s in Russia,’ pointed out Coburg.

‘Yes, but his assassination squads are everywhere, including here in England. I told you that Stalin is paranoid; he’s fearful that the families of his victims might take revenge on him, so he has them killed.’

‘But what threat would someone like Svetlana pose to him?’ asked Coburg.

‘A paranoid person doesn’t need a reason to fear people,’ said Rostov.

‘How did you meet your wife?’ asked Coburg.

‘At work. At the Railway Executive offices. We went out together, then got married last year when we knew war was coming. It seemed the right time.’

‘What about Svetlana? Did she have any romantic attachments?’

Rostov thought it over, then said, ‘To be honest, I don’t know much about her life. Priscilla didn’t like her so she didn’t come here.’

‘You must have seen her at Down Street? You were working there and you’d got her a visitor’s pass.’

‘We agreed that it was best if we avoided one another there to stop questions about who she was and if we knew one another. We came up with the idea that she was a cleaner working there at night, if she was asked.’

‘What about people she met away from Down Street? Her fortune-telling business?’

‘She used to go to hotels in London and leave her card for people to find. If they wanted a consultation, they left a message in a box at the hotel that had her name on it, leaving their name and address. At first she used to take her clients to her room, until she was turned out. Since then I suppose she went to their houses.’

‘You’re not sure?’

‘As I said, I haven’t seen much of her since I arranged the visitor’s pass for her.’

‘Which hotels did she use?’

‘I know she went to The Dorchester, but I don’t know if she used others.’

‘And The Dorchester allowed her to use their place to get customers?’

‘I think she paid them for each one she got.’

‘Who did she pay?’