Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Allison & Busby

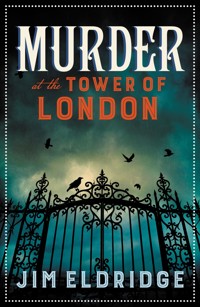

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Serie: Museum Mysteries

- Sprache: Englisch

London, 1899. A shocking murder is discovered at the heart of the Tower of London. The dead body of a Yeoman Warder is found inside a suit of armour belonging to Henry VIII, having been run through with a sword, and when details of this outrage are reported to the Prince of Wales, he fears this may be an expression of Republican unrest striking at the very home of the Crown Jewels. In the hopes of hampering the spread of news about the crime, the Prince reluctantly calls upon the services of Daniel Wilson and Abigail Fenton, the museum detectives, to investigate further. As their inquiries proceed, Wilson and Fenton learn about the long and bloody history of the Tower of London, but dark deeds are not confined to the Tower's shadowy past. More bones will see the light of day and the twists and turns of a dastardly plot will unravel before the museum detectives' case is closed.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 432

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Sammlungen

Ähnliche

MURDER AT THE TOWER OF LONDON

Jim Eldridge

This one, again, is for Lynne, without whom there’d be nothing.

CONTENTS

CHAPTER ONE

London, August 1899

His Royal Highness Prince Albert Edward Saxe-Coburg-Gotha, the Prince of Wales and heir to the throne of Great Britain and Ireland, looked anxiously at Viscount Harold Dillon, the curator of the armouries at the Tower of London as he unburdened himself of his dreadful news.

‘Murder?’ the Prince repeated, shocked. ‘At the Tower?’

‘The body was found in the Line of Kings,’ confirmed Dillon. ‘Though we’re not sure if he was actually killed there.’

The Line of Kings, thought the Prince. The impressive display of life-sized carved wooden horses in the White Tower, installed in the Seventeenth century, during the reign of Charles II, with the armour of each king atop a carved horse. The monarchs depicted were: William the Conqueror, Edward I, Edward III, Henry IV, Henry V, Henry VI, Edward IV, Edward V, Henry VII, Henry VIII, Edward VI, James I, Charles I, Charles II, William III, George I and George II. And me alongside them, thought the Prince, but first I have to become king, which was not looking as certain as it had a few years ago. The Prince was approaching sixty, and his mother, the Queen, seemed as mentally alert as ever at the age of eighty. Yes, she was slower and creaked more, but those who thought she would not last long after her beloved Prince Albert died had been proved wrong. Albert had died almost forty years before, but Victoria seemed determined to live and rule for ever.

‘The victim?’ the Prince enquired.

‘The dead man was one of the Yeoman Warders of the Tower. His name was Eric James. He was found inside the suit of armour belonging to Henry VIII. He had been run through with a sword.’

‘Ghastly!’ groaned the Prince. ‘The police have been informed?’

Dillon nodded. ‘I initially received the report of this tragedy from the resident constable of the Tower, General Sir Frederick Stephenson, and the major of the Tower, Sir George Bryan Milman. They decided that it would be better for the investigation to come under my direction as curator of the armouries. Accordingly, I arranged for Scotland Yard to attend, but I’ve told them that nothing is to be released to the general public, and especially the press. My concern is that a situation such as this – a royal employee murdered on royal premises – might have sinister connotations. As you know, Your Highness, there have been some … activities of late by those people who oppose the very idea of monarchy.’

‘Irish Republicans.’ The Prince nodded unhappily.

‘Not just Irish, I’m afraid. There are radical homegrown elements harbouring the same disgraceful sentiments. My concern is that publicity about this tragic event might encourage those who seek to damage the person and the reputation of the monarchy.’

Prince Albert Edward fell silent for a thoughtful moment, then he turned to look at his private secretary, Michael Shanks, who stood in dutiful attendance, waiting for a command from his master.

‘What do you think, Shanks?’ he asked.

‘Regretfully, I have to agree with the viscount, sir,’ he said. ‘We live in turbulent and unsettled times. We must be constantly vigilant to ensure that what happened in France does not happen here.’

The Prince nodded. ‘Unhappy times indeed. But surely instructing the police not to make the public aware of this hampers their investigations.’

‘That is, unfortunately, a possibility,’ agreed Dillon. ‘I would therefore suggest we look at an alternative.’

‘Private investigators?’ queried the Prince doubtfully. ‘By definition they are limited. They do not have the resources of the police.’

‘True, but there are some who have had great successes in such cases, especially where museums seem to be involved. And the Tower of London is the oldest museum in England.’

Prince Albert Edward looked at Dillon with concern.

‘If you’re suggesting the people I think you are, I must inform you that I have had difficult relations with the gentleman in question, not just in the past but as recently as this year.’

‘But they did prove extremely successful when answering Her Majesty’s request to undertake an enquiry. It was not only successful but it was conducted as Her Majesty had insisted, with the greatest discretion. No mention of it ever appeared in the press.’

The Prince looked unhappy at the prospect, but he deliberated on it, and eventually gave a reluctant affirmative nod.

‘Very well,’ he said. He turned to his private secretary. ‘Shanks,’ he said, ‘send a letter.’

CHAPTER TWO

Daniel Wilson looked full of trepidation as he and his wife, Abigail – known to the public at large as ‘the Museum Detectives’ – approached Marlborough House, the London residence of the Prince of Wales and his wife, Princess Alexandra of Denmark.

‘The last time I was here, the Prince had me thrown out.’

‘But not literally,’ Abigail pointed out.

‘He would have if I’d refused to leave,’ said Daniel. ‘I could tell by the look on his face. His man, Shanks, would have summoned a few more servants and I’d have been sitting on the pavement with my dignity in tatters. Yet today, here we are calling at the Prince’s invitation. I don’t understand it. What’s going on?’

‘The last time you came here it was to question him on his relationship with one of his mistresses,’ Abigail pointed out. ‘That is not the case this time.’

‘I’m still doubtful, about us being here,’ said Daniel. ‘He doesn’t like me.’

‘But he invited both of us,’ pointed out Abigail. And she took the brass bellpull beside the black oak door in her hand and gave it a tug.

At Scotland Yard, Chief Superintendent Armstrong slammed a big beefy fist down hard on the top of his desk.

‘The commissioner himself has ordered a blanket of silence over this matter!’ he snarled, enraged.

Inspector John Feather looked on in what he hoped appeared like sympathy. The fact was that over the years he’d seen the chief superintendent in similar rages when he’d been barred from what he saw as his right to publicity – in this case, the murder of a Yeoman Warder at the Tower of London.

‘A murder in royal premises!’ Armstrong raged. ‘The Tower of London, no less! There could be honours arising out of this case.’

‘We haven’t been barred from investigating the murder,’ Feather pointed out.

‘As good as!’ snorted Armstrong indignantly. ‘No involving the press. No talking to anyone. How are we supposed to catch the killer with our hands tied?’ He looked sharply at Feather. ‘This Dillon character. What’s he like?’

‘Viscount Harold Dillon, sir. The curator of the Tower of London. Quite a reserved sort of man. Very cautious in his manner and his speech. At least, that’s the impression I got when I met him.’

‘Has he got the ear of the royal family?’

‘Definitely, sir. The curator of the Tower is a royal appointee.’

Armstrong scowled. ‘We’ve got to get him to change his mind. We can’t solve this without talking to people. We need information.’

‘Yes, sir,’ agreed Feather, thinking to himself even as he said it: no chance.

‘You’ve got to find a way round this, Inspector,’ said Armstrong firmly. ‘We need to unmask this murderer. As I say, there could be honours at stake here.’

And I have a good idea who’ll be getting them if we do, thought Feather, and it won’t be me.

‘You’re investigating the murder of that Salvation Army officer in Whitechapel, aren’t you?’ asked Armstrong thoughtfully.

‘Yes, sir,’ said Feather. ‘Captain Merchant. He was found beaten to death not far from a pub, the Blind Beggar. By all accounts, the local publicans have no love for the Salvation Army; they accuse them of costing them money with their drive to stop people drinking.’

‘So, the publicans are the chief suspects?’

‘I wouldn’t say chief suspects, sir. There are rumours concerning the immigrant communities in the area, notably the Ashkenazi Jews and the Irish.’

‘No matter,’ said Armstrong dismissively. ‘The point is that Whitechapel is right next door to the Tower of London, so you’ll be over there, on site, so to speak. You can pop in and out without upsetting the curator, this bloke Dillon. Tell him you’re investigating the Salvation Army killing, and you’ve come to update him about the murdered Yeoman. See what he’s got.’

‘But if I say I’m there to update him, he’ll expect some progress,’ pointed out Feather doubtfully.

‘Make something up,’ said Armstrong. ‘The important thing is to be seen to be doing something, so that when a lead pops up at the Tower, it’ll be recalled that we – the Metropolitan Police – were the ones who were there. It was us who cracked the case.’

‘Yes, sir,’ said Feather.

‘Good,’ said Armstrong. ‘We have a plan.’

Daniel and Abigail perched on the sofa in the Prince of Wales’s library and listened attentively as he told them the reason for his summons. A Yeoman Warder had been murdered at the Tower of London and his body stuffed into the suit of armour that had once adorned the body of King Henry VIII, and was now on display in the White Tower as part of the famed Line of Kings.

‘Viscount Harold Dillon, the curator of the armouries at the Tower, feels it could be an act of violent sedition aimed at the royal family,’ said the Prince. ‘The concern is that it may be the tip of the iceberg, and there could be even more dangerous acts to follow. Assaults on members of the royal family themselves.’

Including you, thought Daniel.

‘I would like to commission you to conduct an investigation into this tragic affair and get to the bottom of it. Find out who is behind it. But …’ And as he stressed the word, he fixed them both with a determined look. ‘This must be done with no publicity of any sort. Such publicity could possibly inflame the situation, if it is republican anti-monarchists at work here, and encourage others to follow suit. It is important no word of this outrage leaks out. Not just to the press, but it must be kept from the public at all costs, by whatever means.’

‘We understand, Your Highness,’ said Abigail. ‘We assume the police have been informed. It is a legal requirement …’

‘Yes, yes,’ said the Prince impatiently. ‘They have. Viscount Dillon has been in touch with Scotland Yard. In fact, it was he who suggested we commission you to carry out his investigation, in parallel with the police. But, and I stress again, with no information going out to the press or the general public. That is paramount.’ He looked towards his secretary, Shanks, who sat at a nearby desk. ‘My secretary has prepared a letter to Harold Dillon authorising your investigation. He’ll give you that and you can make yourselves known to Dillon at the Tower. He’ll give you everything you need to know. And you’ll report to him.’

Shanks stood up and said, ‘If you’ll follow me to my office, Mr and Mrs Wilson, I’ll give you the letter, and at the same time fill you in on the background of the organisation of the Tower, which I feel may be of help.’

As Daniel and Abigail followed the Prince’s secretary along the corridor to his office, Daniel mouthed quizzically at Abigail, ‘The organisation of the Tower?’

Abigail nodded and put a discreet finger to her lips, followed by a wink to let him know that she would explain to him later if there was anything he didn’t understand.

Shanks’s office was small and spartan: a desk, his own chair behind it and two other chairs facing the desk. There were no paintings on the walls, no photographs on the desk, the shelves were filled with imposing reference books and registers of Europe’s aristocratic families.

Shanks gestured to the two empty chairs and they sat. He passed them the letter he had prepared authorising them to investigate the murder. ‘I have already sent a copy to Viscount Dillon by messenger,’ he told them. ‘Have either of you been to the Tower?’

‘Some years ago when I was a detective at Scotland Yard,’ said Daniel.

‘And I visited as part of my studies when I was at Cambridge,’ said Abigail.

Shanks nodded. ‘As I’m sure you know, the Tower is a royal palace. The building of the White Tower began shortly after the Norman invasion of 1066. I understand that you are known as the Museum Detectives. Effectively, the Tower is a museum, the oldest in Britain, but it is also a royal palace, and as such it comes under the authority of the Crown.

‘The most senior person in charge of the Tower is the constable. The constable is always chosen from the most senior ranks of those members of the military who have retired from active service. You may recall that earlier this century, the famed Duke of Wellington was appointed constable of the Tower. The current constable is General Sir Frederick Stephenson, a former commander-in-chief of the British Army of occupation in Cairo. The second most senior officer at the Tower is Sir George Bryan Milman, the current major of the Tower of London, also known as the resident governor.

‘However, Viscount Dillon is the person you will be dealing with. He is the curator of the armouries at the Tower, and as it was at the Line of Kings, which comes under the remit of the armouries, where this heinous crime was discovered, it was felt he will be able to give you the best information.’ He looked at them firmly as he added sternly, ‘There is no need for you to approach Sir Frederick or Sir George directly. Anything you wish them to be informed of will be passed to them by Viscount Dillon. Is that clear?’

‘Very clear,’ said Abigail.

He stood up to indicate that their interview was over.

‘The important thing with this case is discretion,’ he said. ‘His Highness has made it clear that there must be no publicity of any sort about this situation. Certainly not any deliberate leakage to the press or any members of the public. Neither should there be any accidental leakages.’

‘We understand,’ said Abigail. ‘You can rest assured we will keep everything secret.’

CHAPTER THREE

They waited until they were at home before discussing their meeting with the Prince and his secretary.

‘Thank heavens we won’t have to deal with those two knights of the realm who are in charge of the Tower,’ said Daniel. ‘I’ve met some of those retired military types and all they ever do is want to talk about the battles they were in and how many of the enemy they slaughtered. At least we won’t have to endure that with this Viscount Dillon.’

‘You don’t know that,’ said Abigail. ‘For all you know he could well be an ex-soldier, especially as he’s in charge of the armouries at the Tower.’

‘Let’s find out,’ said Daniel. He went to the bookcase and took out a thick copy of Who’s Who.

‘He may not be in that,’ said Abigail.

‘Someone with that kind of job has got to be,’ said Daniel, flicking through the pages. ‘In fact, here he is. Harold Arthur Lee-Dillon, 17th Viscount Dillon. Born in Westminster, January 1844. Educated at private school and the University of Bonn in Germany.’ He scanned the rest of the entry before saying, ‘It looks like he did have a military career, although nothing as grand as the two top men at the Tower. He was in the Rifle Brigade and rose to lieutenant, but resigned his commission in 1874. He then joined the Oxfordshire Militia as a captain, promoted to major in 1885. Retired in 1891. Succeeded his father as 17th Viscount Dillon in 1892, the same year in which he was appointed curator of the Royal Armouries.’ He replaced the book on the shelf. ‘The Prince of Wales, a couple of knights and a viscount. It seems that once again we are moving in exalted company.’

‘Not bad for a workhouse boy.’ Abigail smiled. ‘You have definitely risen in the world.’

Viscount Dillon was in his office when Daniel and Abigail arrived at the Tower. He took from Abigail the letter that the Prince of Wales had given them and studied it at some length, even though both Daniel and Abigail knew that Dillon was perfectly aware of the contents of the letter even before they had given it to him.

The viscount was a man in his mid-fifties, balding, thin-faced, with a look of permanent suspicion, not just with Daniel and Abigail but everything he encountered. Daniel and Abigail struggled to reconcile the wary-looking man in front of them with the fact that it was he, according to Prince Albert Edward, who’d recommended that the Prince commission them to investigate the murder. Dillon stroked his small Van Dyke beard thoughtfully as he handed the letter back to Abigail.

‘As the Prince asks, I will do everything I can to help solve this dreadful crime, providing the Tower is not exposed to publicity of any kind.’

‘Absolutely.’ Daniel nodded. ‘We’d be grateful if you could tell us everything you know about the Yeoman Warder who was killed, and any information you may have that might point towards a motive in this case.’

‘Certainly,’ said Dillon. ‘But before I do, I’d like to bring Algernon Dewberry in on this. He’s my deputy curator here at the Tower. If you’ll excuse me for a moment, I’ll go and fetch him.’

Viscount Dillon left the office and returned a few moments later with a tall, thin man in his early forties. Algernon Dewberry was as serious-looking as the viscount, sallow-faced, clean-shaven and with his hair kept short. He shook hands with Daniel and Abigail as they were introduced, and then seated himself beside Dillon’s desk. The viscount slid the letter from the Prince of Wales to him. Dewberry read it, then handed it back.

‘A tragic situation,’ he said.

‘Indeed,’ said Daniel. ‘What can you tell us about the victim?’

‘The dead man was Eric James,’ said Dillon.

‘Had he been with you long?’

Dillon looked at Dewberry, who replied, ‘Six years.’

‘Can you think of any reason why anyone should want to kill him?’

‘Absolutely not,’ said Dewberry. ‘All of our warders have to be of good character. They must have served in the British Army as warrant officers, with at least twenty-two years of service. They must also hold the Long Service and Good Conduct medal.’

‘That’s why I cannot believe his murder was a personal matter,’ said Dillon. ‘It can only have been because he interrupted some criminals engaged in nefarious activity, perhaps some sort of theft, or it was carried out by persons as a form of showing their contempt for all things royal.’

‘Anti-monarchists?’ said Abigail.

‘Sadly, there have been instances recently of such anti-royal actions. You’ll remember the assassination attempts on the Queen?’

Daniel and Abigail nodded. ‘Eight attempts, as I recall,’ said Daniel.

‘And then there was the attempt on the life of the Queen’s second son, Prince Alfred, while he was in Australia.’

Daniel and Abigail both frowned, as they did their best to recall this.

‘It was in 1868,’ said Dillon. ‘He was shot in the back by an Irish republican while he was in Sydney.’

‘That was before our time,’ said Daniel. ‘We were both just infants then.’

‘Was he seriously injured?’ asked Abigail. ‘As Daniel says, it was before our time.’

‘The bullet struck him but glanced off his ribs instead of entering his body. Fortunately, it wasn’t a serious wound and he was nursed back to health. It doesn’t help that certain politicians make speeches calling for the abolition of the monarchy and making Britain a republic.’

Charles Dilke, thought Daniel. The radical Liberal member of parliament who made speeches calling for the abolition of the monarchy. Although a series of scandals in which he’d been named in two divorce cases had lessened his influence on the general public.

Sensing that Dillon was about to enlarge on his theme with more examples of anti-monarchist sentiments, Daniel determined to get the conversation back to the actual murder they were being asked to investigate.

‘What time was Mr James’s body discovered?’ he asked.

‘7.30 a.m. yesterday morning. Another of the warders was starting his rounds and went to the Line of Kings, and noticed that the armour on the effigy of Henry VIII looked as if it had been disturbed. He went to put it back as it should have been, and he became aware there was something inside it. That was how he discovered poor Mr James’s body.’

‘Who was this warder?’

‘Hector Purbright. He was a particular friend of Eric James. He was absolutely devastated by the discovery, but he acted with alacrity and efficiency, as befits a former soldier. He summoned his immediate superior, the divisional sergeant major, who then took over. The sergeant major reported it to me. After discussion with the constable and major of the Tower, it was I who ordered the police to be informed. To avoid tittle-tattle spreading, which might have occurred if we’d summoned a beat constable, I sent one of our warders to Scotland Yard to advise the detective division. He returned with an Inspector Feather and two uniformed officers.’

‘Inspector Feather’s a good man,’ commented Daniel.

‘Yes, that was my impression as well,’ said Dillon.

‘When was the last time anyone saw Mr James alive?’

Dillon looked at Dewberry, who said, ‘We’re still checking on that. Mr Purbright said he spoke to Mr James at about half past nine the previous evening. They were both on their rounds. The warders patrol the grounds while visitors are here to make sure that nothing untoward might be occurring.’

‘So Mr James was killed at some time between a half past nine that evening and seven o’clock the following morning,’ said Daniel.

Dillon shook his head.

‘No,’ he said. ‘The murder must have been committed between half past nine and ten o’clock that night. The main gates are locked every night at ten o’clock without fail. Do you know the ceremony of the keys?’

Daniel shook his head, but Abigail declaimed in dramatic tones, ‘Whose keys are these? Queen Victoria’s keys. Pass then, all is well.’

Dillon nodded. ‘Yes,’ he said. ‘You have witnessed the ceremony?’

‘No, but it came up when I was studying history at Girton College.’

‘Ah.’ Dillon nodded. ‘So you are one of the privileged few.’

‘We had a lecture by one archaeologist who was involved in a dig here at the Tower. They were excavating for Roman remains.’

‘Then you’ll know that once the gates are locked, no one can leave or enter the Tower, except with authorisation, which is recorded in a book. So the only people who would have been inside the Tower would be the resident staff, and I cannot believe that any of them would have committed this outrage. It must have been an outsider who left before the gates were locked for the night.’

‘How many Yeoman Warders are on duty at the Tower?’ asked Daniel.

‘At the present moment, thirty-six,’ said Dewberry.

‘And they all live at the Tower?’

‘They do. Some are bachelors; some are married with families.’

‘Who else lives here?’

‘The constable of the Tower, Sir Frederick Stephenson and his family; the major of the Tower, Sir George Bryan Milman and his family, and Mr Dewberry and his family. It helps to have the deputy curator permanently on site,’ added Dewberry, ‘in case there is an emergency that needs immediate investigation. As the case with the Line of Kings.’

‘Have there been any such emergencies that have called for your attention, Mr Dewberry?’ asked Abigail.

‘Thankfully no,’ said Dewberry. ‘This is the first time it has happened in all the time I’ve been here.’

‘Would it be possible for us to look at the place where the body was discovered?’ asked Daniel. ‘The Line of Kings?’

‘Certainly,’ said Dewberry. ‘I’ll take you there myself.’

Daniel and Abigail followed Dewberry out of Dillon’s office in the New Armouries block and they walked the short distance across a courtyard to the White Tower. Two Beefeaters were on duty at the entrance to the Tower. They stepped aside as they recognised the deputy curator, allowing the three to enter the White Tower. They climbed the wooden staircase to the top floor, where the Line of Kings was on display. Daniel and Abigail exchanged glances, and both knew what the other was thinking: this was a very impressive display. A line of exquisitely carved wooden horses. Astride each was a life-sized suit of armour, each representing a royal ruler.

‘This is one of the oldest exhibits at the museum,’ said Dewberry. ‘It was created in the seventeenth century by Charles II to promote the restored monarchy.’

Daniel walked along the line, reading the name of the monarchs. ‘No queens,’ he observed. ‘No Queen Elizabeth, no Queen Victoria.’

‘Queen Victoria has never worn armour,’ said Dewberry.

‘But Queen Elizabeth did,’ said Daniel.

Dewberry gave an apologetic smile. ‘I believe that King Charles II only wanted kings featured.’

‘A pity, as Elizabeth was one of our strongest and most intelligent monarchs,’ commented Abigail.

Dewberry led them to the armour of Henry VIII.

‘Either this isn’t his real armour, or it’s been made deliberately flattering,’ said Daniel. ‘In portraits I’ve seen of him, he’s a very large man.’

‘It was decided to depict him in his youth. This is the suit of armour he wore as a young man.’

Daniel studied it. The suit of armour was very ornate, but so was the armour that the horse wore. The horse’s chest was protected by what looked like a circular metal skirt with a large boss on each side. The horse’s flank was protected by a wraparound sheet of metal, and on the wooden animal’s head was a metal helmet from its ears – which had their own cone-shaped metal protectors – down to the creature’s mouth.

‘The protection on the horse’s front, around its chest, is called the peytral,’ said Dewberry, noting where Daniel was looking. ‘The metal protecting its rear is known as the crupper. The whole thing is called the bard.’

‘It’s not until you get up close you realise that every inch of the armour, the rider’s and the horse’s, are decorated with very fine engraving,’ said Daniel.

‘The decoration is the work of Paul van Vrelant of Brussels, who was Henry’s harness gilder,’ said Dewberry.

Abigail joined them in examining the intricate engravings on the metal.

‘The work is incredible,’ she said. ‘Beautiful. Delicate and so clear.’

‘The figures depicted are St George and St Barbara, the patron saints of Henry and his then wife, Katharine of Aragon,’ said Dewberry, pointing them out.

‘Is it heavy?’ asked Daniel.

‘Not a heavy as you might think. It’s made of steel, offering enough protection without weighing the wearer down.’

‘It would have taken some difficulty to put a dead body inside that particular suit of armour. How tall was Eric James, and what sort of build did he have?’

‘He was quite a short man, and of narrow build, so I think he would have fitted inside the suit of armour without too much difficulty. The police have removed his body to Scotland Yard, so you’ll be able to examine it there.’

‘Is this area patrolled at night?’ asked Daniel.

‘There’s no real need,’ said Dewberry. ‘Once the gates have been closed for the night, only the residents are on site. He looked at his watch. ‘Is there anything else you need to know at this moment? I know you’ll want to talk to Yeoman Purbright, who found the body, and others who might have been witnesses.’

‘Indeed.’ Daniel nodded. ‘But we think that’s enough for the moment. Thank you for your assistance.’

CHAPTER FOUR

As they walked away from the Tower, Daniel asked, ‘What’s your opinion of that morose-looking pair, Dillon and Dewberry?’

‘As you say, morose. But then, having a dead Beefeater suddenly appear in the White Tower is hardly going to cheer them up. What do you think about what Dillon said – it must have been an outsider?’

‘In my opinion he’s bound to say that,’ said Daniel. ‘His duty is to protect the reputation of the Tower, and that includes everyone who works in it. Personally, I’ve got an open mind. We need to talk to John Feather.’

They decided to take the Underground because there was a direct line from the Tower to the Embankment, which made their journey faster than if they travelled by bus, and also because ever since she’d been introduced to London’s underground railway system, it was Abigail’s preferred choice of getting around the city.

They walked into the large reception area at Scotland Yard, both of them keeping a wary eye open for their particular nemesis, Chief Superintendent Armstrong, and made for the reception desk, which today was manned by an old friend of theirs, Sergeant Callum McDougall.

‘Mr Wilson, Mrs Wilson.’ McDougall beamed. ‘Good to see you again. I trust you are keeping well.’

‘We are indeed, thank you, Sergeant. We’re here to see if Inspector Feather is available.’

‘He’s supposed to be. I can send a message up to his office.’

‘That would be much appreciated. Before you do, is Chief Superintendent Armstrong also in?’

‘He is indeed.’

‘In that case, would you send this up to Inspector Feather?’

Daniel took a sheet of paper and wrote on it:

John, we are in reception and going to Freddy’s. We’d be grateful if you would join us there for coffee. Daniel & Abigail.

McDougal took it and grinned as he read it.

‘You’re not banned again, surely,’ he asked.

‘Not as far as we know, but there’s no sense in tempting providence,’ said Daniel.

McDougall summoned a messenger and gave him the note, folded over, with instructions to take it to Inspector Feather’s office. Abigail pointed to a device on the reception desk, a bulky object with a wire coming from it, and a separate piece of equipment resting in a cradle on the top, also with a length of wire trailing from it.

‘I see Scotland Yard are getting modernised,’ she said. ‘A telephone. We came across them when we were in Manchester.’

‘The plan is to have one in every office in the building,’ said McDougall. ‘But at the moment this is the only one here, and it’s for emergency use only.’ He looked at it suspiciously. ‘To be honest, I’m still not sure how useful it will be.’

‘The ones we saw in Manchester were very useful,’ said Abigail. ‘You can talk to people almost anywhere in the country.’

‘Yes, but they can also talk to you,’ said McDougal doubtfully. ‘And maybe they’re people you don’t want to talk to.’

Daniel and Abigail made their way to Freddy’s, the coffee bar close to Scotland Yard that served as an unofficial meeting place for police personnel. They ordered three coffees, which were being delivered to their table as the slim figure of John Feather entered the café and joined them.

‘I assume some sort of intrigue is afoot if we’re meeting here,’ said Feather, taking his seat.

‘Yes and no,’ said Abigail. ‘We don’t consider it intrigue, but the chief superintendent might if he knew about our latest commission.’

Feather gave them a broad grin. ‘Let me guess. The Tower of London.’

‘You’ve heard?’ asked Abigail, surprised.

‘No, but it was a logical step in view of how you handled the last case involving the royal family. Who contacted you?’

‘The Prince of Wales,’ said Daniel.

‘So, orders from the very top,’ said Feather, impressed, as he sipped at his coffee.

‘We weren’t sure how Chief Superintendent Armstrong would react once he found out,’ continued Abigail.

‘We thought he might ban us from the Yard again,’ added Daniel. ‘He tends to do that when he gets upset with us. He’s convinced we’re trying to undermine him, but we’re not.’

Feather lapsed into thoughtful mode for a few moments, then said, ‘There may be a way round this, and actually persuade Armstrong to let us work together. Albeit unofficially, but with his personal approval.’

‘How?’ asked Daniel.

‘The royal family have insisted there must be no publicity of any sort. No press, nothing to the general public.’

Abigail nodded. ‘That’s what we were told very firmly by the Prince himself, and by Viscount Dillon.’

‘Which has infuriated the superintendent because it effectively ties our hands. We can’t even talk about it to some of our uniformed officers in case word leaks out. However, if I tell Armstrong that you’ve been commissioned by the Prince himself, and suggest that I keep in close contact with you, finding out what you’re up to in the case and following up any likely leads, we stand a good chance of getting to the bottom of things. And, as there’s been a bar on word about this getting to the press, any arrest would be made by Scotland Yard, so we – or rather, he – gets the credit.’

Daniel and Abigail exchanged looks, and smiled at one another.

‘Do you think he’d agree?’ asked Abigail.

‘I think he’d leap at the opportunity,’ said Feather. ‘After all, we’re getting nowhere with it, and unlikely to with the restrictions placed upon us.’ He smiled. ‘This way, if anything did leak out, he could blame you two.’

‘Not something that would please our patron,’ said Daniel unhappily.

‘I’m confident you two could assure him it wasn’t your fault,’ said Feather. ‘The thing is it would mean we could work together, swap information. After all, there’s no credit to be gained from this if there’s not going to be any publicity. But Armstrong would claim the credit with the commissioner, and at the moment he needs every bit of credit he can get.’

Abigail nodded. ‘That’s agreed, then. You sell him that idea, and you and us keep each other abreast of what’s going on.’

‘Agreed,’ said Feather.

‘So, let’s start by you telling us what you’ve got,’ said Daniel.

‘The biggest thing I’ve got is that James’s twin brother, Paul, was murdered two days before Eric was murdered. Paul James was stabbed to death.’

Daniel and Abigail stared at Feather, shocked at this news.

‘So the murders are connected!’ said Daniel.

‘That’s my feeling,’ said Feather. ‘The problem is that the Prince, and also Viscount Dillon, aren’t being very cooperative about Scotland Yard investigating the murder of Eric James. They’re terrified that news will leak out about the murder and get into the papers. They’re insisting that the two murders could be coincidence.’

‘So the authorities at the Tower are in denial,’ said Abigail.

‘Which ties our hands for investigating both murders as being connected,’ said Feather. ‘It was the people who found Paul James’s body who told us that his twin brother, Eric, was a Yeoman Warder at the Tower. So we got hold of Eric James to identify his brother’s body. But Eric didn’t give any indication that he might know why Paul was killed. He admitted to us that he hadn’t had much to do with his brother, that Paul was a ne’er-do-well, a drunkard who went about with bad companions. Eric was a very respectable Yeoman, a teetotaller.’

‘Yes, Dillon told us he was eminently respectable, a holder of the Good Conduct and Long Service medal as all Yeomen have to be,’ said Abigail.

‘Eric was obviously upset at what had happened to his brother, but he said considering the people he mixed with, his death in that violent way hadn’t come as a surprise,’ added Feather. ‘One thing we didn’t reveal to Eric, because we thought it would only upset him further, was that Paul’s tongue had been cut out.’

‘The underworld warning to others to keep their mouths shut,’ said Daniel.

‘Exactly.’ Feather nodded. ‘Which suggests he was involved in something criminal and someone had got word he was about to grass on them, or they suspected he might. Which is why I’m saying it may not be connected to the killing of Eric James. Having met Eric and learnt about his good character, I don’t believe he would have been a party to any criminal activity involving his brother.’

‘It still sounds like there might be something there,’ said Daniel.

‘If we’re exchanging information, what have you got so far about Eric James’s death?’ asked Feather.

‘Only what we learnt from Harold Dillon. Eric James was a Yeoman Warder of impeccable character. His dead body was found inside the armour of Henry VIII in the Line of Kings in the White Tower. He’d been run through with a sword. Dillon is convinced he must have been killed by an outsider and that the murder happened before ten o’clock at night, when the gates to the Tower are locked, but we have our doubts about that.’

‘The doctor reckons he was killed some time between nine o’clock and eleven o’clock, give or take an hour either side,’ Feather told them.

‘He was last seen alive at half past nine, so that reduces the time-frame,’ said Daniel. ‘It still means it could be an outsider, or one of the residents. Who have you spoken to so far at the Tower?’

‘Hardly anyone,’ said Feather with a sigh. ‘Viscount Dillon is being very protective. The only person I was allowed to question was the man who found the body, Yeoman Warder Hector Purbright, but I was only allowed to do that in the presence of Viscount Dillon, which meant that Purbright kept looking at his boss the whole time and only gave very short and not very helpful answers. My advice is for you to talk to Purbright alone. I was told he was Eric James’s closest friend amongst the people at the Tower. You’ve got the backing of the Prince so you should be able to talk to him on his own, away from Dillon. Purbright’s also the Ravenmaster at the Tower.’

‘Ah, the ravens,’ said Abigail with a smile. ‘“If the Tower of London ravens are lost or fly away, the Crown will fall and Britain with it”.’

‘How do you know so much about the Tower?’ asked Daniel.

‘The history of Britain formed part of the Classical Tripos at Cambridge. Only a small part, admittedly, but those of us who found it fascinating did our own research. The Tower is, after all, almost a thousand years old, that’s a large span of this country’s history.’

‘You said you were investigating two murders in the area,’ said Daniel. ‘Whose is the other one?’

‘Edward Merchant, a captain in the Salvation Army,’ Feather told them. ‘He was found beaten to death not far from the Blind Beggar pub on Whitechapel Road. With the Salvation Army’s emphasis on abstinence from alcohol, there have been attacks on Salvation Army officers by thugs hired by pub owners, upset at their loss of revenue in places where the army’s anti-booze campaign has had an effect. This could well be another such attack but one that got out of hand.’ He paused, then added, ‘It was outside the Blind Beggar pub that William Booth gave his first sermon against the evils of the demon drink. I wondered if it was a coincidence that this Salvation Army captain was killed at the same place where General Booth made his speech that launched the Salvation Army. Sending a message, so to speak.’

‘It’s feasible,’ agreed Daniel. ‘Any suspects?’

Feather shook his head. ‘You know what Whitechapel’s like, Daniel, from the time you were there on the Ripper case. No one sees or hears anything. It’s just going to be a matter of painstaking questioning until we catch someone out.’

CHAPTER FIVE

As Feather walked through the main doors of Scotland Yard after leaving Freddy’s, he saw Chief Superintendent Armstrong standing at the reception desk talking to Sergeant McDougall. The superintendent had obviously been asking after Feather, because Feather saw McDougall point towards him. Armstrong turned, saw him, and came striding towards him.

‘Where have you been?’ demanded Armstrong.

‘I’ve been doing as you ordered,’ said Feather. ‘Getting inside information on the dead Beefeater at the Tower.’

‘Who from?’

‘The Wilsons.’

Armstrong looked at Feather, suspicion on his face. ‘How come they’re involved?’

‘The Prince of Wales has hired them to look into the case.’

‘Damn! It would be them!’ Armstrong scowled, and Feather fully expected him to punch a wall or a desk. Fortunately, they were at a distance from either.

‘But this could be to our advantage,’ said Feather quickly.

‘How?’ demanded Armstrong.

‘It might be better if we talked about it in your office,’ said Feather. ‘Away from prying ears.’

‘Yes, good point,’ said Armstrong.

Feather followed the chief superintendent up the wide marble staircase to the first floor, and then into Armstrong’s office, where Feather told him of his conversation with Daniel and Abigail.

‘In short, we work unofficially together, but at the end when we’ve unmasked the killer, the police get the credit because the Wilsons have promised the Prince of Wales there’ll be no publicity,’ Feather finished.

‘So what’s in it for the Wilsons?’ asked Armstrong suspiciously.

‘They get paid. Plus, the top nobs in society will get told about it by the Prince during social chit-chat because he won’t be able to resist telling his cronies how clever he was in hiring the Wilsons to solve the crime.’

Armstrong thought it over, then asked, ‘You sure they’ll tell you whatever they discover?’

‘They have on previous occasions,’ said Feather. ‘I’ve always found them to be honest. And, as I said, they won’t be able to claim any credit for it because of their promise to the Prince.’

Armstrong nodded. ‘Right. Do it. But watch your step. We don’t want to upset the royal family, so no publicity leaks from us.’

‘There won’t be,’ Feather assured him.

Daniel and Abigail returned to the Tower to seek out Yeoman Purbright, but this time Daniel stopped on Tower Green and began to look around him.

‘What’s the matter?’ asked Abigail. ‘Have you had a sudden thought about the case?’

‘No,’ said Daniel. ‘I must admit that when we came here before to talk to Viscount Dillon, my mind was on what we would find. I was thinking about Eric James being killed and stuffed inside that suit of armour. But now, I’m noticing the Tower of London properly and taking it all in.’ He gestured at the old wooden Tudor buildings on the green. ‘Look at them. How long have they been here?’

‘Since Tudor times at least,’ said Abigail. ‘Possibly before that.’

‘Five hundred years,’ said Daniel.

He looked at the high defensive walls that surrounded the vast area of the Tower. ‘Look at the stonework. Can you imagine how long it took to do all this?’

‘It was developed and expanded over hundreds of years,’ said Abigail. She gestured at the huge bulk of the White Tower that dominated the centre of the whole place. ‘The White Tower was started in the 1070s, soon after William had conquered England, and it was completed in 1100. So, almost forty years.

‘The rest of the place was developed a few hundred years later, after Richard the Lionheart came to the throne. He wanted the whole place strengthened. However, as he headed off to the Crusades almost as soon as he became king, he left the work in making the Tower into a proper fortress in the hands of his chancellor, William de Longchamp, the Bishop of Ely. It was the Bishop who doubled the size of the Tower. Later, Henry III went even further. Those very tall defensive curtain walls you admire were his creation.’

‘Making it an impregnable fortress,’ said Daniel.

‘Almost,’ said Abigail. ‘In the case of Richard, no sooner were the walls in place than his brother, John, mounted an attack on the Tower, aiming to take control. Longchamp held out as long as he could, but John laid siege and, in the end, when Longchamp’s supplies ran out, he was forced to surrender.’

‘And John became king.’ Daniel nodded.

‘Yes, but not then. When Richard returned form the Crusades, he took control of the Tower, and the country, back from John. John begged his brother’s forgiveness, which Richard granted. He also named John as his successor. And that’s when we have the reign of Bad King John.’

‘Amazing,’ said Daniel. He headed for the White Tower. ‘I’m so glad you’re here to tell me about all this. Not having had a proper education, it’s a place that’s just been here, but I don’t know the details, just the most well-known bits. The Crown Jewels. The Traitor’s Gate.’

‘Oh, there’s a lot more to this place than those,’ said Abigail. ‘If we’re here long enough, I’ll take you on a tour.’

They found Yeoman Purbright patrolling inside the White Tower on the same floor as the Line of Kings. The crowds of visitors had been allowed back in and Purbright was keeping a close watch on them. Daniel produced the letter of authority from the Prince of Wales and handed it to Purbright, who read it then handed it back.

‘As you can see, we’re here at royal command,’ said Daniel. ‘We just need to ask you a few questions, if that’s all right.’

‘What about?’ asked Purbright.

It suddenly struck Daniel that, instead of reassuring him, the Prince’s letter seemed to make Purbright more nervous.

He’s suddenly being asked to take on a responsibility that he doesn’t want, realised Daniel.

‘I suggest we talk outside,’ said Daniel. ‘It’ll be more private.’

Purbright nodded and followed Daniel and Abigail outside to Tower Green.

‘We understand from Inspector Feather at Scotland Yard that Eric’s twin brother, Paul, was killed just two days before Eric himself was murdered, and Eric was the one who identified his brother’s body,’ said Daniel.

‘Yes,’ said Purbright.

‘We’re curious that you didn’t mention this to Inspector Feather when he talked to you after Eric’s death.’

‘He already knew about it,’ said Purbright. ‘Eric told me that an Inspector Feather had taken him to look at Paul’s body.’

‘But you didn’t discuss it with Inspector Feather when he was here after Eric was killed,’ persisted Daniel.

Purbright hesitated, then said reluctantly, ‘Viscount Dillon told me it wasn’t appropriate to talk about it. He said it would have had nothing to do with Eric’s murder. So that was the answer I gave when the inspector asked me about Paul James. That I’d been told by my superiors that it wasn’t a matter to be discussed.’

Daniel and Abigail exchanged concerned looks; this was what Feather obviously meant when he’d told them that the people at the Tower weren’t being co-operative and were tying his hands. Aloud, Daniel said, ‘With respect to the viscount, this information is very appropriate. I think you need to tell us everything you know about Eric James and his brother.’

‘You think it’s connected with Eric’s murder?’

‘Two brothers are killed within two days of one another. That certainly suggests a connection of some sorts.’ He looked thoughtfully at Purbright. ‘Did Eric and Paul have much to do with one another?’

‘No,’ said Purbright. ‘I never met Paul, but from what Eric told me about him, I got the impression they were two very different sorts of men. They would have had nothing in common. That’s what Viscount Dillon said to me before the inspector talked to me in the viscount’s office, which is why it wasn’t considered appropriate to talk about with the inspector.’

Daniel studied the unhappy Yeoman, who seemed to be struggling with some sort of internal turmoil. Then Daniel said, ‘I’m told that Eric was a good man. I can’t believe he just ignored what was happening to his brother. There’s something more, isn’t there?’

The unhappy Purbright looked away from Daniel’s probing gaze.

‘We need to know everything if we’re going to catch Eric’s killer,’ Daniel pressed. ‘Paul was killed, then Eric. We’re sure there’s a connection between both murders. What were Eric and Paul involved in together?’

‘Nothing!’ burst out Purbright. ‘Not in that way. Lately Eric had been trying to help Paul turn his life around and get on the straight and narrow.’

‘How was he doing that?’

‘About a week ago, Eric persuaded Paul to accompany him to a local Salvation Army Mission Hall to listen to General William Booth speak. Eric hoped that listening to General Booth would help him turn away from his life of wickedness. Eric was convinced that Paul’s troubles stemmed from drink. Paul seemed as if he was prepared to take heed, but things must have gone wrong for him again, because he was killed. Stabbed to death.’

‘Was Eric a member of the Salvation Army?’ asked Daniel.

‘No. He went to a few meetings, but he couldn’t join. The Salvation Army expects its officers to work for them full-time. That was out of the question for Eric, so long as he was a Yeoman Warder in the British Army. But Eric was very sympathetic to the Salvation Army and the good work they do.’

‘Before Eric took Paul to that meeting, had they had much to do with one another recently?’ asked Abigail.

‘No,’ said Purbright. ‘I don’t think they’d had any sort of contact for a year.’

‘So who got in touch with who? Did Eric seek out Paul, or Paul seek out Eric?’

Purbright thought about it, then said, ‘It was Paul. He came here to the Tower looking for Eric.’

‘When was this?’

‘About a month ago. Eric told me about it afterwards. He said Paul had turned up looking for him and asked one of the other Yeomen where he could find him. He told the Yeoman he was Eric James’s brother. The Yeoman went and found Eric and brought him to the public area where Paul was. Eric told me that Paul said he’d come to ask Eric for help.’

‘What sort of help? Financial?’