8,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Atlantic Books

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

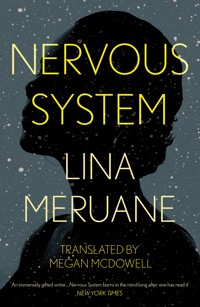

'Nervous System is fast, uncompromising and shimmering with intelligence' Sarah Moss, author of Summerwater 'Meruane is one of the one or two greats in the new generation of Chilean writers who promise to have it all' Roberto Bolaño A young woman struggles to finish her PhD on stars and galaxies. Instead, she obsessively tracks the experience of her own body, listening to its functions and rhythms, finally locating in its patterns the beginning of illness and instability. As she discovers the precarity of her self, she begins to turn her attention to the distant orbits of her family members, each moving away from the familial system and each so different in their experiences, but somehow made similar in their shared history of illness and trauma, both political and personal...

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

Also by Lina Meruane and available in English

Seeing Red

Originally published in 2018 as Sistema nervioso by Penguin Random House Grupo Editorial, Santiago.

First published in hardback in the United States of America in 2021 by Graywolf Press.

First published in hardback in Great Britain in 2021 by Atlantic Books, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright © Lina Meruane, 2018

Translator copyright © Megan McDowell, 2021

The moral right of Lina Meruane to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

The moral right of Megan McDowell to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities, is entirely coincidental.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Hardback ISBN: 978 1 78649 947 9

EBook ISBN: 978 1 78649 948 6

Printed in Great Britain

Atlantic Books

An Imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

To my brothers in orbit.

A system has not just one history but every possible history.

Stephen Hawking on Richard Feynman

contents

black holes *

explosion *

milky way *

stardust *

gravity *

black holes

* restless present *

The country went dark. One giant black hole, no candles.

In another time, another place, her house had been full of long skinny nebulous candles, wrapped in blue paper or tied with string, kept for emergencies.

There were no candles in the country of the present, where the electricity never went out. Never, until it did.

Ella watched as the lamp that half lit her face and scarcely lit the night died. She sat for a moment with her hands hovering over the keyboard, blinking in the light of a screen full of numbers. Ella. She. Wondering whether a fuse had blown. Whether it was just a simple blackout or an attack on the old nuclear power station built and abandoned during the Cold War. Not too far from her building, atomic energy that could explode any minute now.

Forever on the verge of catastrophe, her country of the past used to suffer power outages from floods, or from snow falling on trees and from branches onto electrical posts. Exposed cables electrocuting the wind. Ditches and rivers overflowing. And buildings that shuddered from the constant grinding of subterranean plates. Volcanoes crackled, spraying lava. Forests burned, trees fell, scorched to their roots, houses to their foundations, the signs roads hives melted, birds flapping. Their bodies charred if they didn’t get out fast enough.

Those bodies, possessed by the light.

* * *

This is going to slow me down, Ella cried, throwing up her arms. More, it’s going to slow me down even more, and she howled at El. He. To El, who had surely already heard her in some corner, slamming drawers, searching in vain for a flashlight. She rummaged through papers and keys and she cursed. El’s inflammatory voice rose to tell her, stop that, Electron. It was the same thing he’d been saying to her for months, that she should shut her computer, disavow her doctoral thesis and the anxiety brought on by the life sentence of a project like that.

Working such long hours could set her off. That’s what El said, and he knew about explosions. But he didn’t say explode and he didn’t say collapse. He said, burning his tongue on a fresh cup of coffee he was now balancing in the dark. As though spitting, he said, short-circuit.

And Ella saw a quick spark traverse his nerves. His skin covered with hairs, ignited vibrating electric.

* * *

Now even the most indistinct, insignificant stars spattered the night with their light. They seemed to give off smoke, fiery above the extinguished city. Ella paused at the window to admire them. The radiant constellations, the pulverized physical universe that she couldn’t manage to capture in the dissertation she’d been writing for years. Years without writing. She’d started out studying elliptical orbits and their magnetic fields, the asteroid belts and the remains of millenary supernovas; she’d spent months or maybe even years on the star systems closest to the sun, searching in vain for habitable planets, and she hypothesized the positions of celestial bodies similar to earth. One thing led to another, each refuting the one before, obliging her to start her research all over again.

This final attempt would be spent on stars that had already lost their light and collapsed in on themselves, forming dense black holes.

Except those holes needed an adviser who knew all about them and was willing to guide her dissertation. One who believed Ella was prepared to deal with such density. But not even Ella was sure she could do it, and time was running out.

* * *

And then the bulbs all came on simultaneously, as though electrified by lightning. Reactivated after an interval of hours. Ella opened a can of coke, loaded with sugar and caffeine—she would drink to her own detriment before sinking once more into the screen. She would calculate figures of cosmic deviation and radiation. She would measure the movement of the stars stretched out around the spinning greedy point-of-no-return black hole that would soon swallow them. And she’d type formulas she would later proceed to disprove.

El would see her appear in the doorway, that morning and the ones to come, and the scar across his forehead would wrinkle. Ella would understand that he, too, had stopped believing she could finish.

* * *

It was while thinking about blackouts and bottomless holes that the desire to get sick ignited in her. Ella considered it but couldn’t decide on an illness. A cold or a flu wouldn’t give her the time she needed to finish the thesis. Pneumonia would keep her from working. Cancer was too risky. Then her memory turned to her Father’s bleeding ulcer, which had kept him bedridden for several months: she imagined herself lying in a different bed, computer on her lap, eating poached eggs and insipid crackers and taking irritating sips of coca-cola on the sly.

To fall ill: Ella would ask the favor of her birth mother, her deceased genetic mother. The one she never met. Ella always invoked her when things got hard. Lighting a stick of incense, she begged her mother to infect her with something serious but transitory. Not to die like the mother herself, suddenly. Just enough to take one semester off, to not have to teach all those planetary sciences classes to so many distracted students whom she had to instruct evaluate forget immediately. Just a brief reprieve from that poorly paid job so she could dedicate herself fully to another job that paid nothing at all.

Ella had no one else to ask. Her Father had already given all he had.

* * *

Secret-pact story. No one knew the Father had funded her studies in the country of the present with savings for his future old age. Ella’s three siblings and that Mother who wasn’t hers had been left out of their mutual agreement. Because the Mother who came to fill in for the first would never have allowed it. All that money! she would have cried in defense of her disinherited twins. It’s a fortune! she would argue, fearing the indignities the expense could entail for the Father.

The Father would never have told his second wife that this was the promise he’d made to the first, in critical condition after her daughter’s birth. Promise me Ella will study what she wants, that you’ll pay for whatever program she chooses without any conditions, the first wife murmured in a voice that wavered but knew death was coming. It’s what I would have wanted. What I would have done. Study. If I hadn’t, and she stopped, closed her eyes a long second. Gotten married, she said, the words coming unstrung. So young, to you. What I would have.

* * *

El, hair combed, face freshly shaved, already finishing breakfast, ready to head off to the carbon laboratory to date some newly dusted bones. Ella, dressed but unkempt, dragged herself into the bedroom to choose her teacher’s uniform and assemble her notes for the five classes she would teach that day in three different city schools. Dull-eyed, she sat down at the table and confided in El what she wanted. To get sick. To have six months free. To stay home alone with her two hands, the eighty-two keys under ten fingers tapping intermittently. To leave her fingerprints on a thesis that was missing arduous weeks of work.

Be careful what you wish for, is what El replied in his language, the language of Ella’s present, knitting his brows into a single line. His sharp nose pointed to the empty plate as he murmured his warning. You don’t need your dad’s approval, he said with a weary air, you don’t even need to tell him you haven’t finished, that you might not ever finish. You don’t need that degree, Electronica, not to teach astronomy classes. Extraterrestrial planetary sciences, corrects Ella.

Ella hadn’t admitted to El that she never had a scholarship, or told him where all that money, down to the last red cent, had really come from, from whose pocket, nor had she told him she’d just called her Father to tell him, I’ve defended, dad, I’m a doctor now. Or that her Father replied sadly or perhaps resentfully that it was about time, hija. That her Father had fallen silent before informing her that she was now the only real doctor in the family. A doctor in the true sense of the word, murmured her Father, while Ella’s throat tightened.

Ella didn’t know why she’d lied, but that, too, was a lie.

* * *

Be careful, and El got up from the table and left without saying goodbye.

Nine weeks, sixty-three days, 1,512 hours later, Ella was still the lackluster inhabitant of that apartment where, more than live with El, eat with El, sleep with El, entwine her legs with his until their bodies blended together, she shut herself away to work. The exams had been corrected, her students assigned grades. She’d finished the semester without a sneeze, without a migraine, but now summer was starting and time was entirely her own again, and she would work without interruption.

And Ella typed, yes, but then she stopped, she got distracted, wrote text messages full of typos, found excluded terms in lists, jotted down unconnected words that rhymed but were useless to her, in spite of their strange beauty. And she bit a nail until it bled, or scratched her leg and made a cup of tea with milk and peered out the window and then went back to her chair.

* * *

Lean back, stretch both arms. Bend a stiff neck forward and to one side. A sudden cramp shoots down the spine and then, stillness.

* * *

In that hot, wet summer there was only the anguished breeze from an ancient fan.

Rushed notches numbers on the wall as days and hours passed. 1,564. 1,598. 1,613. And in all those hours Ella still didn’t move, an electric pillow propped under her neck. Cursed be the too-high table, the hard chair that now forced her into a horizontal position. Cursed be the stabbing pain every time she changed position.

Two more days and I’ll go back to work, Ella decreed, turning up the current as high as it would go.

* * *

To have wanted to burn. Both hands suspended in the air, Ella had raised the small can of kerosene and gulped it down. The body that was hers at five years old didn’t retain the flavor of the fuel her Grandmother used to stir up orange and blue flames in the fireplace.

She couldn’t recall what happened next.

* * *

Turning off the electric pillow and getting out of bed, Ella thought about first-degree burns: an unbearable stinging had settled into her shoulder neck ember. Sitting at her computer, she felt an invisible wound wrapping her up and suffocating her. The summer was still reheating the bricks outside, and Ella, who burst into flames when she moved, who died on getting dressed, decided to work naked in the kitchen.

Only the spinning blades on the ceiling soothed the burning.

The only thing that mattered now was the bonfire in her shoulder.

* * *

Had she sought out the burn, or had she mistakenly put her hand through the grate that protected the scorching burner of the stove? The mark left by that deliberate childhood accident is now just a faded spot on her skin, a scar that back then must have covered the entire back of her hand.

* * *

Inflammatio. In flames. En llamas. Ardor without romance.

The ancient philosopher of inflammation had grown cold twenty centuries ago and lay stiff underground. But he couldn’t be lying there, not stiff or dressed or naked, Ella thought, but disintegrated and scattered beneath the ruins. El had explained it to her; he was her bone expert: there would be nothing left of that cadaver, not a splinter or a gram of brain sweat chest hair. Only calcium and phosphorus. And hydrogen atoms, Ella said, molecules. That body would no longer be exposed to the slightest possibility of inflammation, which, as the same thinker had described, was distinguished by four basic principles.

Rubor. Calor. Dolor. Tumor.

Those were the signs Ella had looked for on her own back, angling a mirror between her shoulder blade and clavicle. It wasn’t red. Not swollen or hot to the touch. There was no trace of damage, but the pain was like another skin.

* * *

Instead of dialing her Father it was El she called, to share the burning enigma with him. There was no sign she’d burned herself. It’s not even red but it hurts, Ella explained, as she spread toothpaste over lumbar torso dead tongues. But El knew only about desiccated bones. I don’t know what to tell you, and his voice sounded distracted, or maybe hostile. He couldn’t help her from the remote country where he was attending a conference, but she went on talking as though to herself, holding the phone with pasty fingers. I must have burned myself on the inside, underneath, it’s the only explanation I can think of.

El had warned her. Too many hours working. Too many all-nighters and whole days of electric heat on a muscle. Too much abandonment of what they had once been. But he didn’t say it again. Ask your Father, he said instead.

* * *

And that’s how the summer gradually dies. Like that, grudging, half-dressed, and smelling of menthol, not a single line further in the manuscript, resolved to abandon her thesis until the burning subsides, she gets on a plane to meet El in the remote conference country.

That remote, provincial city, so damp and fresh, so shaken by nocturnal winds, is a relief.

And though the burn and its ghost persist, their intensity wanes. The anxiety eases, but between Ella and her symptom something else settles in: a slight numbness that starts in the shoulder and extends along the arm to the elbow until it reaches the back of her right hand, the fingers where it all started.

That was just speculation—maybe it didn’t start there. Her defective shoulder blade and arm allowed for other readings. Because now it wasn’t just shoulder arm carpal tunnel but also the base of her skull, the edge of her face, her tongue.

Under the warm shower at the hotel where they’re staying, Ella notices her skin has faded away. She touches it but feels nothing. The towel slides like a breeze over her back.

And when El touches her, what does he feel? But it’s been a long time since he touched her. When he looks at her, does he see her disappearing?

* * *

Ella typed arm falling asleep in her search bar, and then she couldn’t fall asleep.

She wrote to a neurologist in the land of the present but he was the kind of doctor who was stingy with words, replying in monosyllables when he even remembered to respond to her messages. Then she turned to her Father, even though numb, sleeping arms weren’t his specialty, and the Father said over the phone, from the antipodes of the past, that it didn’t seem necessary to rush back for a case of paresthesia. The neurologist agreed, in a laconic, unpunctuated line sent in the future tense, that a pinched nerve was no cause for alarm. But her Father’s opinion, in another call to the remote country, was that it couldn’t be a pinched nerve. The Mother’s opinion was the same. Ella’s firstborn brother cracked his knuckles. No one consulted the other siblings.

Only El stayed nervously silent.

* * *

And the woman Ella has called Mother ever since she met her is the one who sends text messages every morning to ask about the arm where that strange sleep is spreading. And Ella writes back with a brief report: no change, no news. And signing off to that Mother who is hers but not, she types: thanks for checking in, I arm fine! Only after she sends her message does she notice that her dyslexic fingers have injected an r.

* * *

Portrait of a rebellious arm leaning against the elevator doors every time they came up from the parking garage. Don’t lean on that, it’s dangerous, warned her Father, but Ella rested the weight of her childhood on those rusty doors that slid back over themselves, screeching. The steel sheets opened at the sixth floor and caught her jacket sleeve, her soft muscles, her humerus bone. And the stuck doors and the Mother screaming roaring goat bellows, afraid her arm would be separated from her body, when the Father grasped hold of her with his giant hands and yanked her out.

Her Father gave her an unforgettable beating that Ella has, nevertheless, forgotten.

The daughter sitting on the Father’s lap. The daughter drying her eyes while her Father tells her a story that she has also forgotten. So many moments are asleep in her memory.

* * *

This is her forced vacation in a remote country. It’s always worse in the afternoons.

Waiting for the doctor that the hotel has called for Ella, they both order soup and sip it stealthily in the lobby. Again and again they look up from their bowls to see if he’s arrived, but the doctor walks right past them like a ghost stripped of his sheet, then leaves without ever seeing them.

They’ll have to wait until he finishes his evening rounds, wait for him to return for the lost arm and it’s already noon. Bells ringing from the church towers.

* * *

The doctor was named after a soccer player, but his examination style was more like that of a trainer or masseuse. He asked her to perform a series of coordinated movements in the small hotel room. Walk forward and back, in a straight line. Lift her arms while he pressed down on them to measure her strength. Touch the tip of her nose with one index finger and then the other, follow his finger as it traced a horizontal line in the air. He put a knuckle between each pair of vertebrae and asked if it hurt, he palpated her head in search of bumps, he twisted her neck as she let it go limp. He blew on her toes after touching them with a pin. He couldn’t reach a diagnosis. Maybe it was a nerve pinched by a disk, he said, indecisive, but we’d have to get an x-ray.

Tapping the table with just-trimmed nails, the Father waits as his daughter relays the doctor’s verdict from the remote country. He insists on talking to the doctor himself, and the two of them discuss her fate, which will be worse if the Father is right. The masseuse-doctor prescribes an injection that the Father vetoes, and the discredited doctor shrugs his shoulders and gives up, backs off, returns the receiver with her Father inside.

It’s not a strangled nerve, insists the impatient Father at the other end of the line. That nerve’s path doesn’t match your symptoms. And in the deep voice of the professor he has also been, he merely starts listing the signs that would indicate a brain hemorrhage or tumor.

* * *

Between the remote hotel sheets, Ella rubs the numbed edge of her face as if she could wake it up. Her eye wanders again over medical websites that link paresthesia to diseases that end in paralysis. The eye rolls, falls out, hits the keyboard, and wakes El, who grunts, please, turn that off.

El takes her cold hand, interlaces one finger with another finger stiff magnetic under the weather until he catches them all. The rough skin that unites and abrades them. The index finger that shuts off the light. The wrist that bends. The palm of the hand that covers her eyelids and keeps her from reading.

Those websites that her Father categorically forbade her. But up till now, out of all of them, the doctor she’s ignored the most has been her Father.

* * *

Back in the city of the present, the neurologist sits with Ella’s fingers between his own; they are fragile, cold, as if rather than holding her hand, he were looking for a pulse.

That doctor will decree punished vertebrae and a nerve crushed by excess work or all the papers that she carries on ramps bridges trains city skeletons. And that tingling in her face—is she perhaps nervous? The doctor unfurls an involuntary smile, inappropriate, unbearable, a convulsive smile: your nervous face. Nerves or nervousness, who knows? No one knows, Ella thinks. The neurologist should know, but he’s a prejudiced doctor. I’m a woman, but that doesn’t make me crazy. That thought radiates through her cheeks and spatters her tongue. Could be it’s not a pinched nerve, Ella emphasizes, emulating her Father. It is a nerve, replies the doctor, loudly underlining the verb. Could we check, just to be sure? Ella asks, following, in plural, the suggestion of the doctor or masseuse back in the remote country. We’re completely sure, Ella sees the neurologist say, rubbing his eyelids under bushy brows, absolutely sure, that’s what he’s saying, drawing out the u in his absoluteness and his surety. Unless you insist, and he pauses to size her up, the doctor gnashing his polished teeth before Ella, who insists, I would absolutely insist, hiding her crooked teeth, the molars full of cavities worried by her tongue.

We know exactly what the images will show, the doctor proclaims, rising victoriously from his chair, his duplicate fingers typing up the order for the MRI.

* * *

To orient themselves as they plunge into the night, bats emit hundreds of cries, at different frequencies, which bounce back to report on all that moves in the area. Everything this blind creature cannot see takes on shape, volume. Resonance, echo, is medicine’s blind howl. A sonorous ray of images in the body’s impenetrable darkness.

* * *

Ella had never been in the echo chamber. The Mother, who has gone through it, recommends that she close her eyes and try to focus on something pleasant. Surrounded, though, by the grapeshot of shrill beeps and the peals of exasperating bells, Ella can’t manage to find a single soothing place to take refuge. Bad memories assail her. The call informing her of the attack at El’s excavation. El’s head, all bandaged full of silence, and hers, full of fear. She’s besieged by imaginary radioactive stations—bombs made of the same hydrogen that lights the stars—with pigeons shitting oxide all over them. Her investigation full of holes that she doesn’t know how to fill. Perhaps she’ll have to live with that, Ella thinks, die with that, kill someone with that—her Father, always on the verge of collapse.

Suddenly, the beeping of the machine changes, softens, speeds up, and she’s seized by a wind, relentless as the resonant chamber she’s inside. Waves rise up against rocks while Ella sinks down into the ocean, letting the current carry her out to sea. She is swimming in the sound, crossing or trying to cross a turbulent southern strait where so many scurvy-filled sailors ran aground, so many ships masts rodents of conquest. The ocean rears up, curves into a foamy crest, lifts, and drops her in a crash of hardened water. Her ears are stopped up as she moves through thunderous upswellings, focuses on her breathing. Almost there, she tells herself, exhausted, inhaling and exhaling without losing the rhythm, almost to the shore, she tells herself, filling her mouth with air and salty water, swallowing the ocean whole again and again, and again.

* * *