6,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

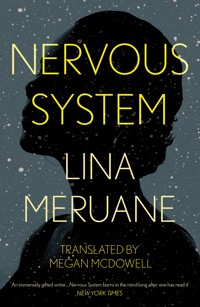

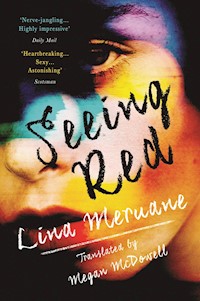

- Herausgeber: Atlantic Books

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

Winner of the Premio Valle Inclán (Spanish Translation) 2019 - Awarded by The Society of Authors Winner of the prestigious Mexican Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz Prize 2018 'A scorching examination of how being utterly dependent on someone - even someone you love - can make you a monster' -- Literary Hub, Translated Books by Women You Need to Read Lucina, a young Chilean writer, has moved to New York to pursue an academic career. While at a party one night, something that her doctors had long warned might happen finally occurs: her eyes haemorrhage. Within minutes, blood floods her vision, reducing her sight to sketched outlines and tones of grey, rendering her all but blind. As she begins to adjust to a very different life, those who love her begin to adjust to a very different woman - one who is angry, raw, funny, sinister, sexual and dizzyingly alive.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Ähnliche

SEEING RED

SEEING RED

—

Lina Meruane

TRANSLATED FROM THE SPANISH BYMEGAN McDOWELL

First published as Sangre en el ojo in Chile in 2012 by Pangea Libros.

First published in the United States of America in 2016 by Deep Vellum Publishing, Texas.

First published in hardback in Great Britain in 2017 by Atlantic Books, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright © Lina Meruane, 2012

Translator copyright © Megan McDowell, 2016

The moral right of Lina Meruane to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

The moral right of Megan McDowell to be identified as the translator of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities, is entirely coincidental.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Hardback ISBN: 978 1 786 493 132

E-Book ISBN: 978 1 786 493 149

Printed in Great Britain

Atlantic Books

An Imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

To Paul,keeping watch in the darkness

I raised my head in horror and saw Lina staring at me with black, glassy, motionless eyes. A smile, between loving and ironic, creased my beloved’s lips. I jumped up in desperation and grabbed Lina roughly by the hand.

“What have you done, you wretched woman?”

CLEMENTE PALMA, Los ojos de Lina (Lina’s Eyes)

burst

It was happening. Right then, happening. They’d been warning me for a long time, and yet. I was paralyzed, my sweaty hands clutching at the air, while the people in the living room went on talking, roaring with laughter—even their whispers were exaggerated, while I. And someone shouted louder than the rest, turn the music down, don’t make so much noise or the neighbors’ll call the cops at midnight. I focused in on that thundering voice that never seemed to tire of repeating that even on Saturdays the neighbors went to bed early. Those gringos weren’t night owls like us, party people to the core. Good protestant folks who would indeed protest if we kept them from their sleep. On the other side of the walls, above our bodies and under our feet, too, these gringos—so used to greeting dawn with their socks on and shoes already tied—were restless. Gringos who sat down in their impeccable underwear and ironed faces to eat their breakfasts of cereal with cold milk. But none of us were worried about those sleepless gringos, their heads buried under pillows, their throats stuffed with pills that would bring no relief as long as we kept trampling their rest. If the people in the living room went on trampling, that is, not me. I was still in the bedroom, kneeling, my arm stretched out toward the floor. In that instant, precisely, in that half-light, in that commotion, I found myself thinking about the neighbors’ oppressive sleeplessness, imagining them as they turned out the lights after stuffing earplugs in their ears, how they’d push them in so hard the silicone would burst. I thought I would much rather have been the one with broken earplugs, the one with eardrums pierced by shards. I would rather have been the old woman resolutely placing the mask over her eyelids, only to yank it off again and switch on the light. I wished for that while my still-suspended hand encountered nothing. There was only the alcoholic laughter coming through the walls and spattering me with saliva. Only Manuela’s strident voice yelling over the noise for the umpteenth time, Come on, guys, keep it down a little. No, please don’t, I said to myself, keep talking, keep shouting, howl, growl if you must. Die laughing. That’s what I said to myself, my body seized up though only a few seconds had passed. I’d only just come into the master bedroom, just leaned over to search for my purse and the syringe. I had to give myself an injection at twelve o’clock sharp but now I wouldn’t make it, because the pile of precariously balanced coats let my purse slide to the floor, because instead of stopping conscientiously, as I should have, I bent over and reached to pick it up. And then a firecracker went off in my head. But no, it was no fire I was seeing, it was blood spilling out inside my eye. The most shockingly beautiful blood I have ever seen. The most outrageous. The most terrifying. The blood gushed, but only I could see it. With absolute clarity I watched as it thickened, I saw the pressure rise, I watched as I got dizzy, I saw my stomach turn, saw that I was starting to retch, and even so. I didn’t straighten up or move an inch, didn’t even try to breathe while I watched the show. Because that was the last thing I would see, that night, through that eye: a deep, black blood.

dark blood

There would be no more admonitions impossible to follow. Stop smoking, first of all, and then don’t hold your breath, don’t cough, do not for any reason pick up heavy packages, boxes, suitcases. Never ever lean over, or dive headfirst into water. The carnal throes of passion were forbidden, because even an ardent kiss could cause my veins to burst. They were brittle, those veins that sprouted from my retina and coiled and snaked through the transparent humor of my eye. To observe the growth of that winding vine of capillaries and conduits, to keep watch day by day over its millimetric expansion. That was the only thing that could be done: keep watch over the sinuous movement of the venous web advancing toward the center of my eye. That was all and it was a lot, the optician declared, just that, that’s it, he would repeat, averting his eyes and looking at my clinical history that had grown into a mountain of papers, a thousand-page manuscript stuffed into a manila folder. Knitting his graying eyebrows, Lekz wrote the precise biography of my retinas, their uncertain prognosis. Then he cleared his throat and subjected me to the details of new research protocols. At one point he dropped the phrase transplants in experimental stages. Only I didn’t qualify for any experiments: I was either too young, or my veins too thick, or the procedure too risky. We had to wait until the results were published in specialized journals, and for the government to approve new drugs. Time also stretched out like arbitrary veins, and the eye doctor went on talking nonstop, ignoring my impatience. And what if there’s a hemorrhage, doctor, I was saying, clenching his protocols between my teeth. But it didn’t bear thinking about, he said; better not to think at all, he said, better to just keep an eye on it and take some notes that would be impossible to decipher later on. But soon he would raise his eyes from his illegible calligraphy to concede that if it happened, if it came to pass, if in fact the event occurred, then we would have to see. Then you’ll see, I muttered, holed up in my hate: I hope you can catch a glimpse of something then, once I no longer can. And now it had happened. I no longer saw anything but blood in one eye. How long would before the other one broke? This was finally the blind alley, the dark passage where only anonymous, besieged cries could be heard. But no, maybe not, I thought, getting hold of myself, sitting down on the coats in that bedroom of Manuela’s, folding my toes inward while my shoes swung like corpses. No, I told myself, because with my eyes already broken I would dance again, jump again, kick doors open with no risk of bleeding out; I could jump off the balcony, bury the blade of an open pair of scissors between my eyebrows. Become the master of the alley, or find the way out. That’s what I thought without thinking, fleetingly. I started to ransack the drawers in search of a forgotten pack of cigarettes and a lighter. I was going to burn my fingernails lighting the cigarette, fill myself with tobacco before returning to that doctor’s office and saying to him, the smoke now risen to my head, tell me what you see now, doctor, tell me, coldly, urgently, strangled by resentment, as if his gloved hands had wrenched my sick eye out by its roots: tell me now, tell me whatever you want, because now he couldn’t tell me anything. It was Saturday night or more like Sunday, and there was no way to get in touch with the doctor. And in any case, what could he say that I didn’t already know: liters of rage were clouding my vision?

that face

As I put out the cigarette and straightened up, I saw a thread of blood run across my other eye. A fine thread that immediately started to dissolve. Soon it would be nothing but a dark spot, but it was enough to turn the air around me murky. I opened the door and stopped to look at what remained of the night: just a pasty light coming from what must be the living room, shadows moving to the rhythm of a murderous music. Drums. Rock chords. Discordant voices. There would be appetizers languishing on the table, and potato chips, a dozen beers. The ashtrays must still be only half-full, I thought, without actually seeing them. The party stayed its course and no one had any intention of stopping it. If only the wide-awake gringos would start banging on the walls with their broomsticks, I thought. If only the cops would come and make us turn off the music, put away all that old Argentine rock, pick up the trays with stony faces. If only they would make us put our shoes on, toss back the last dregs in the bottles, tell the last tired joke, hurry through the goodbyes and see-you-laters. But the early morning still stretched out ahead of us. Of me. Of Ignacio, who was still indiscernible in the fog. Ignacio would understand the situation without my needing to say get me out of here, take me home. I was sure his panting exhaustion would come to my rescue, his finger poking my cheek. Why so serious?, he said, suddenly beside me. Hearing his voice shattered my composure, dashed it to the floor as he added: Why the long face? And how was I to know what kind of face I had, when I’d misplaced my lips and my mole, when even my earlobes had gotten lost. All I had left were a couple of blind eyes. And I heard myself saying, Ignacio, chirping Ignacio like a bird, Ignacio, I’m bleeding, this is the blood and it’s so dark, so awfully thick. But no. That wasn’t what I said, but rather, Ignacio, I think I’m bleeding again, why don’t we go. Go? he said (you said it, Ignacio, that’s what you said even though now you deny it, and then you fell silent). And I heard him ask if it was a lot of blood, maybe assuming it was like so many other times, just a bloody particle that quickly dissolved in my humors. Not so much, no, I lied, but let’s go. Let’s go now. But no. Let’s wait until the party winds down, till the conversation dies of its own accord. Let’s not be the ones to kill it, as if it weren’t already dead. We’e leave in a little while, and what’s an hour more or half an hour less when there’s no longer anything ahead. I could drink another glass of wine and anesthetize myself, another glass of wine and get drunk. (Yes, pour me another glass, I whispered, while you filled it up with blood.) And I drank to the health of my parents, who were snoring miles away from the disaster, to the health of my friends’ uproar, to the health of the neighbors who hadn’t complained about the noise, the health of the medics who never came to my rescue, to the motherfucking health of health.

stumbling along

And we all left the party together, saying nothing but thanks, see you later, bye; and I guess the group gradually scattered along the way, because I can’t see them in my memory. The elevator was full of voices, but when we went outside there were only three or four bodies, and then only one walking next to me. Julián was telling me about his job talk at the university or who knows what, while I moved deeper into unprecedented darkness. Ignacio would be behind us, talking his Spanish politics with Arcadio, or maybe he’d gone off to hunt for a taxi. At that hour, on that scrawny island wedged in next to Manhattan, it wouldn’t be easy to find a cab. We’d have been more likely to come across an abandoned wheelchair with a loose spring. A chair would have helped me, made me less vulnerable to the night’s uncertainty. A chair, so much better than a cumbersome cane. And I thought back to that very afternoon when we’d crossed over the river in the tramway along with a dozen people, variously maimed, in their wheelchairs. Roosevelt was an island of wheelchairs where only a few professors and students lived, and no tourists came; it was a poor, protected island that almost no one visited, I thought, thinking next that I should have realized why I’d ended up traveling with all those people beside me, them and me all the same hanging above the waters. On the shore stood Fate and he was raising a question, an admonition. What did you come here looking for? he said, pointing one finger. What did you lose on this island? A chair, I answered, outside of time and circumstance, just a metal chair, with wheels, with pedals and levers and maybe even a button to propel it forward. If only you’d had a little more foresight, you would have your chair, answered my dour inner voice. At least you’d have one for tonight, when you were going to need it. But now the maimed would all be sleeping soundly, with their chairs disabled and parked next to their beds. Mine, my bed, which wasn’t mine but rather Ignacio’s, was still far away. Everything seemed far from me now, and getting ever farther. Ignacio had disappeared and Julián quickened his pace, spurred on by the beers. I was inevitably being left behind. I moved in slow motion, sliding over the slippery gravel, plummeting off curbs, stumbling over steps. Julián must have come back when he realized he was talking to himself, I felt him supporting me by the elbow and saying fizzily, “I’d better help you, looks like you’re a bit drunk, too.” He started to laugh at me and I also started shaking in an attack of panic and booming laughter. And in that laughter or those convulsions Julián dragged me forward, interrogating me, did my feet hurt?, were my knees stuck?, because, joder, he said Spanishly, why the hell are you going so slow? I kept walking with my eyes fixed on the ground as if that would save me from falling, and with my head sunk miserably between my shoulders I tried to explain what was happening: I left my glasses at home, I can’t see anything. Glasses! And since when do you wear glasses? You’ve kept that nice and hidden! he exclaimed, wasted and dead tired. And warning me that we were walking through a stretch of wet grass, he went on repeating, I can’t believe it! You never wear glasses! Never, it was true. I had never bought a pair of glasses. Until twelve o’clock that night I’d had perfect vision. But by three o’clock Sunday morning, even the most powerful magnifying glass wouldn’t have helped me. Raising his voice and maybe also his finger, like the university professor he would become, Julián brandished his ragged tongue to chastise me. You get what you deserve. And, swallowing or spitting saliva, he announced that the price of my vanity would be to trudge through life, forever stumbling.