6,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

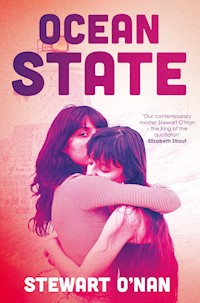

- Herausgeber: Grove Press UK

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

When I was in eighth grade my sister helped kill another girl. For the Oliviera family - mum Carol, daughters Angel and Marie - autumn 2009 in the once-prosperous beach town of Ashaway, Rhode Island is the worst of times. Money is tight, Carol can't stay away from unsuitable men, Angel's world is shattered when she learns her long-time boyfriend Myles has been cheating on her with classmate Birdy, and Marie is left to fend for herself. As Angel and Birdy, both consumed by the intensity of their feelings for Myles, careen towards a collision both tragic and inevitable, the loyalties of Carol and Marie will be tested in ways they could never have foreseen. Stewart O'Nan's expert hand has crafted a crushing and propulsive novel about sisters, mothers and daughters, and the desperate ecstasies of love and the terrible things we do for it. Both swoony and haunting, Ocean State is a masterful work by one of the great storytellers of everyday American life.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

Also by Stewart O’Nan

FICTION

Henry, Himself

City of Secrets

West of Sunset

The Odds

Emily, Alone

Songs for the Missing

Last Night at the Lobster

The Good Wife

The Night Country

Wish You Were Here

Everyday People

A Prayer for the Dying

A World Away

The Speed Queen

The Names of the Dead

Snow Angels

In the Walled City

NONFICTION

Faithful (with Stephen King)

The Circus Fire

The Vietnam Reader (editor)

On Writers and Writing by John Gardner (editor)

SCREENPLAY

Poe

Copyright © 2022 by Stewart O’Nan

First published in the United States of America in 2022 by Grove Atlantic

First published in Great Britain in 2022 by Grove Press UK,an imprint of Grove Atlantic

Copyright © Stewart O’Nan, 2022

The moral right of Stewart O’Nan to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced,stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by anymeans, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise,without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of the book.

1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2

A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library.

Hardback ISBN 978 1 61185 655 2

Export trade paperback ISBN 978 1 61185 433 6

E-book ISBN 978 1 61185 878 5

Printed in Great Britain

Grove Press UK

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.groveatlantic.com

For Angel OlsenHi-Five.

Sometimes our enemiesare closer than we think

Angel Olsen

Shut up kiss me hold me tight

Angel Olsen

In the House by the Line & Twine

When I was in eighth grade my sister helped kill another girl. She was in love, my mother said, like it was an excuse. She didn’t know what she was doing. I had never been in love then, not really, so I didn’t know what my mother meant, but I do now.

This was in Ashaway, Rhode Island, outside Westerly, down along the shore. That fall we lived in a house by the river, across the road from the mill where my grandmother had met my grandfather. The Line & Twine was closed, posted with rusty NO TRESPASSING signs, but just above the dam someone had snipped a hole in the fence with bolt cutters so you could sneak in the back. We used to roller-skate up and down the aisles between the dusty looms, Angel weaving, teaching me how to do crossovers and go backwards. She could do spins like an ice-skater, her hands making shapes in the air. I wanted to do spins and be graceful like her, but I was chubby and a klutz and when I stood beside her in church I was invisible. My mother said I shouldn’t worry, that in time I’d find my special talent. “I was a late bloomer,” she said, as if that was supposed to be comforting. What if I didn’t have a special talent? I wanted to ask. What if a hopeless nerd was all I’d ever be?

My mother’s talent was finding new boyfriends and new places for us to live. She worked as a nurse’s aide at the Elms, an old folks’ home in Westerly where my great-aunt Mildred lived, and didn’t make any money. Fridays she’d come home and change, brushing her hair out, making up her face, using too much perfume. She’d been a cheerleader and could dance. She dieted, or tried to. Facing the narrow mirror on her closet, she complained that nothing fit her anymore. I used to look like you, she told Angel, like a threat, and it was true, in her old pictures they could have been twins. If she’d wanted to, she said, she could have married a doctor, but they were all assholes. Your father was sweet.

We knew our father was sweet. What we didn’t understand was when he’d become an asshole, or why. My grandmother had never liked him because his family was Portuguese. He’d tricked my mother into turning Catholic and then abandoned her. Never trust a Port-a-gees, she said, like it was a joke. I had his dark hair and eyes, so what did that make me?

My mother’s boyfriends tried to be sweet, but they were strangers. Sometimes they paid our rent and sometimes we split it. When they broke up with my mother—suddenly, drunkenly, their shouting jerking us from sleep—we would have to move again. Like her, we were always rooting for things to work out, far beyond where we should have. Our father was gone, and our mother couldn’t stop wanting to be in love. “I swear this is the last time,” she’d say, dead sober, and a month later she’d bring home another loser. They seemed to be getting younger and scruffier, which Angel thought was a bad sign. My mother didn’t seem to notice. In the beginning, everything was new. She lost weight and kissed us too much and made promises she couldn’t keep.

The last had been a deckhand named Wes who brought home lobsters and called her “Care” and took us to Block Island to ride bikes, until one night he smashed her phone when she tried to call the cops on him. Neither of them was bleeding, so the cops didn’t charge anyone. “You guys are useless,” my mother said. “Yeah,” one of them said, “that’s why we’re here at one in the morning, cause we got nothing better to do.” We were living in the top half of a duplex, and the next morning while Wes was out dragging the Sound, the three of us lugged everything we could carry down the stairs and shoved it in my mother’s car.

The house by the Line & Twine was for sale, but in 2009 no one was going to buy it. My grandmother had worked in accounting with the owners, snowbirds who’d shipped off to Florida long before the Crash. Like most of the houses on River Road, it had been sitting empty for years. There was moss on the shingles and weeds in the gutters.

My grandmother came over to help us clean the kitchen. She brought her rubber gloves. “It’s not the Taj Mahal,” she said.

“It’s fine,” my mother said, as if we wouldn’t be there long. “Angel Lynn. Quit with the face.”

“I didn’t say anything,” she said, scowling.

“You don’t have to.”

I didn’t say anything. I hardly ever said anything, afraid of making things worse. I watched them like a scorekeeper, silently recording every slight and insult, every failure to be kind. I was thirteen, and like all children, had an overdeveloped sense of justice. I wanted everyone to be happy, despite our actual lives.

At the duplex, Angel and I had shared a bedroom. Here we each had our own, our doors closed. Lying in bed, I missed her texting with her friends long after I’d stopped reading, the glow on her face as she concentrated soothing as a nightlight. My secret wish was that when I started high school I would magically turn into her, that I would inherit her powers, not just her looks and toughness but the confidence that attracted people to her, the knowledge that no matter what, she would always be wanted. Now, without her, in the dark, with the road silent and the river spilling over the dam behind the Line & Twine, that dream seemed even more unreachable.

Our father hadn’t completely abandoned us. He still came by to do repairs like fixing the doorbell or snaking the shower drain, a constant problem with our long hair. He had us every second weekend, taking us surfcasting, letting us drive his truck on the beach. The summer people were gone, the mansions where he did landscaping shuttered for the season, their spiked iron gates chained. The clam shacks and Del’s Lemonade stands were closed, and we’d end up in town for lunch at One Fish Two Fish, a grease pit in an old Burger King where we’d gone when we were little. It still had the original bright yellow-and-orange Formica booths, the tabletops chipped and dirty at the edges, every stray grain of salt visible. We didn’t have a lot to say to one another, as if we were afraid of giving away secrets that might be used against us. We talked about school mostly, and Angel’s job at CVS. He had an apartment in Pawcatuck over a Chinese restaurant, the whole place saturated with the smell of burnt cooking oil. He had to move the heavy sea chest he used as a coffee table to set up the pullout couch from Bob’s he’d bought just for us, the same faded Little Mermaid sheets every time, though we’d long outgrown Ariel. Sunday, while my mother and grandmother were at church, we slept late and he made us waffles, another leftover from our childhood, before delivering us home. In our driveway, letting us out, he gave us each a twenty, as if tipping us. For our mother, sometimes he had a check and sometimes he didn’t, depending on how business was. They fought bitterly over money, which embarrassed us, and it was a good weekend when he had the full payment. I stayed on the porch to wave him away while our mother and Angel went inside.

“How was it?” our mother asked. “What did you all do?”

“Nothing,” we said. “The usual.”

She wasn’t really interested, and we were already searching for clues to what she’d done with her weekend, sniffing the air for any hint of weed or body spray, checking the ashtrays for Marlboro butts, the recycling bin for extra beer bottles.

One Sunday, Angel found the foil corner of a condom wrapper under our mother’s nightstand. She showed it to me on the palm of her hand like evidence.

“So what?” I pretended I wasn’t frightened by the idea of another stranger taking over our home.

“So she’s fucking someone.”

“Der.”

“She was probably fucking drunk. She probably didn’t even know the guy. I’m so grossed out right now. She’s such a fucking skank.”

I wanted to defend our mother. She was lonely and didn’t know what else to do. “At least he’s not still here.”

“Just wait,” Angel said, and she was right.

The next Friday our mother warned us that Russ was coming to pick her up. He was a fireman but also had a landscaping business. We expected him to have a truck like our father, but the car that pulled up was a little silver Honda like our grandmother’s. Russ was shorter than our mother, and bald, with thick bifocals and a salt-and-pepper beard and a gut that stuck out over his belt. Instead of skinny jeans and motorcycle boots, he wore forest-green corduroys and brown loafers. He had a chunky class ring, and shook our hands limply, like Reverend Ochs after church. Our mother made a point of saying they were going out to dinner, then to a movie at the Stonington Regal, as if they hadn’t met at a bar.

“Weird,” Angel said as we watched them drive off.

“Yeah.”

“He’s like Papa Smurf.”

“That’s mean,” I said.

“Oh Carol, I want to put my smurf in your smurf. I’m going to smurf you all smurf smurf.”

I slapped her on the shoulder and we laughed, bumping into each other like teammates.

“Oh my God,” she said. “What if he’s the one?”

“Stop.”

“It’s sad, actually. It’s like she’s giving up.”

“He’s not that bad,” I said, because I thought she was still joking, but when I looked at her she was wiping away tears.

“Ange, come on.”

She turned her back so I wouldn’t see and reached for a tissue, blew. She hated to cry, thinking it made her weak, but she cried all the time. “It’s so fucked-up. She’s just going to make it worse. You make a mistake, you fix it, you don’t make it again, you know?”

“Yeah,” I said, but I was too frightened to admit I didn’t know what we were talking about anymore. Her boyfriend Myles, I guessed, because normally Angel would be with him, the two of them cocooned in their own little world. By the time I realized what she meant, it was too late.

The girl my sister helped kill was named Birdy Alves. On the news they called her Beatriz, but everyone at school called her Birdy. She played soccer and softball and worked at the D’Angelo on Granite Street. She was petite, with big eyes and a heart-shaped face. Like Angel, she was popular, but she was from Hopkinton, a totally different clique.

Right around Halloween, Birdy Alves disappeared. For weeks the whole state was looking for her. Every night we’d see her face on the Providence news. If you have any information, they said, please call the Hopkinton police.

I loved my sister. I didn’t want to believe she’d lie to me. Even now I want to believe she was trying to tell the truth that night our mother went out with Russ the firefighter, to warn me not to be like her. She might have. Nothing had happened yet. Later the police would put dates to everything, but for now we were two girls alone in a house on a Friday night with nowhere to go. We made popcorn and snuggled under an afghan on the couch with the lights out and watched Mystic Pizza, one of my mother’s favorites, trading the bowl back and forth, our feet in each other’s laps. She was Julia Roberts, I was Lili Taylor. It didn’t matter that half the time she was on her phone. We didn’t have to speak. All I wanted was to be close to her like this, the two of us laughing at the same places. She was the only one who knew what we’d both been through, and I liked to think we were inseparable, bound by more than just blood. We weren’t happy that fall, in that rotting, underwater house, with everything we’d already lost, and everything still to come, but lying safe and warm under my grandmother’s afghan, eating popcorn and stealing glances at my funny, beautiful sister as the light played over her face, I wished we could stay there forever.

1

Saturday Birdy’s supposed to work her regular shift, ten to six, or so she’s told everyone. Coming out of her mouth, it sounds like an alibi, the times too precise, when there’s no need. Everyone knows her schedule.

Last night she couldn’t sleep, and the light in the bathroom’s too bright. In the mirror, the lacy red bra she’s saved for today looks cheap, like she’s trying too hard. She buttons her ugly uniform over it, ties her hair back, ducking her chin, trying not to meet her eyes. They’re bloodshot and watery, not how she wants to look for him, and now she’s caught, unable to look away.

What kind of person is she? Doesn’t just asking that mean she has a conscience? She can’t answer, lets the question pass. She’s not going to stop anyway, so what’s the point? Everything’s wrong. It’s cold and supposed to rain, canceling her daydreams of walking hand in hand with him on the beach, spreading a blanket in the dunes and lying down beside him to watch the clouds sail by. Behind her, sprawled on the bath mat, their cocker Ofelia watches her brush her teeth and rub lotion into her hands, stands before she’s finished and points at the door, wagging her stubby tail like Birdy might take her with her.

“Stop. I can’t open it when you’re in my way.” She understands she’s being mean, but that only makes her more impatient. Ofelia knows her work clothes.

In her room she slips her makeup bag into her purse and sees she has one piece of gum left.

It’s a bad idea, the whole thing. She’s always thought of herself as honest, not perfect but good at heart, and the ease with which she’s become this new, reckless Birdy is confusing, as if someone or something else has taken control of her. It’s a kind of possession, a power greater than herself that at once exalts and leaves her helpless. It’s not worth losing Hector over, yet here she is, already lost herself. Sometimes she doesn’t care. Sometimes she wants to be nothing. The desire scares her, like her desire for Myles, at once baffling and all-consuming.

Downstairs her mother is sewing baby clothes for Birdy’s new niece Luz in the Florida room, singing an old fado to herself like her grandmother used to. My friend, I hate to leave you. The machine chatters, stops, chatters again. If she could just sneak out without having to face her mother, she thinks, but the stairs, the door, the whole house creaks. Ofelia bounds down ahead of her, giving her away, the traitor. Before descending each step, Birdy has to think, like she’s forgotten how to walk.

The machine chatters as she pulls on her puffy coat. She could go, just make a break for it, but she stands with her keys in hand, waiting for the needle to stop.

“I’m leaving,” she calls.

With a scraping her mother gets up from her chair and comes to see her off, tottering on her bad knees, the good water glasses inside the hutch tinkling as she crosses the dining room. Her mother is the wisest person she knows, attuned to the whole family’s moods. She knew Josefina was pregnant with Luz before Josefina did. Now Birdy’s sure she can tell, and hugs her too tightly, makes a show of taking her stupid visor from its peg. Everything she does is a lie.

“We’re having meatballs for supper. I figured I’d use up that hamburger before it goes bad.”

“Good idea.”

“Can you grab some Parmesan on your way home?”

“Sure,” she says, knowing she’ll never remember. She’ll have to set a reminder on her phone.

Outside, the sky’s brighter than she expected, light trying to break through the clouds. In the car it’s a relief to slide on her sunglasses, like they might hide her, but there she is in the mirror, eyeless, alien. She might be an assassin from the future, coolly carrying out her mission, except she can’t stop her thoughts. On the radio, the DJ makes a joke about the rain, talking over the opening of Rihanna’s “Umbrella,” and she turns it off. When Myles had texted her, asking what she was doing Saturday, she threw her hands up and danced around her room like she’d won something. Now she has to remind herself that people do this all the time. She’s not special.

She drives like she’s going to work, down through Ashaway, where Hector’s already punched in at the Liquor Depot. It’s twenty-five miles an hour here, a speed trap to catch beach traffic coming off of 95. She doesn’t want to get stopped, and slows as she passes the lot, hoping he’ll see her go by, proof of her innocence. She searches for his Charger with its expensive rims—parked safely at the far end where no one can scratch the paint. When they first started dating, he’d come visit her at lunchtime, giving her his order, until she told him she didn’t like it.

“What? I think you look cute in your uniform.”

“I do not look cute, so don’t, okay? I’m not joking.”

“Okay,” he said, disappointed, as if she were spoiling his fun. Lately Hector makes her feel as if she’s being stingy, fending him off when he wants to hold her closer. He loves her, he says. He wants to marry her someday, have a houseful of babies like Kelvim and Josefina. He always wants something she’s unwilling to give. How can she explain that she barely thinks of him? He never listens anyway. Myles asks her to tell stories about herself and hears every word.

Beyond the village post office, the speed limit changes back to forty, the oil-black river flashing through the trees, foaming over low dams. She’s passed the long mill and the granite works with its uncut headstones a thousand times, so why do they call to her today? It’s not just her mood, it’s a spooky time of year. The leaves are turning, Halloween’s not that far off. They’ve already decorated at work, the front window hung with gauzy cotton spiderwebs. She imagines herself there, prepping for lunch, the doors locked, her biggest worry Sandra jamming the slicer.

She told Mr. Futterman she had a wedding to go to, making up a cousin. She knew he’d be fine with it. She never asks for Saturdays off, and the day shift is easy to cover.

Normally she’d take 3 all the way into Westerly. Now, before signaling for the turn onto the bypass, she checks her mirrors as if she’s being followed—only a Roto-Rooter van that shoots past as she slows and takes the on-ramp. The bypass is a single lane each way, separated by a Jersey wall. Even in the off-season there’s a steady line of traffic. She merges and settles in behind a pickup, just as the first drops of rain dot the windshield.

“You couldn’t wait, could you?” She pulls off her sunglasses, folds them with one hand and drops them into the cupholder with her phone. A sprinkle at first, the rain gradually accelerates, tapping the glass, and by the time she reaches the light at the Post Road she has her wipers on high.

Again, the day is ruined, every sign arrayed against them. She can still end this, curl through the lot of the Stop & Shop and head back, swing by Elena’s and confess before she does anything stupid, the two of them laughing at her Mission: Impossible trip. Chica, what are you thinking? I mean, Myles Parrish, boy is fine—I’m sorry, Hector—but what in the actual fuck are you thinking?

I don’t know, Birdy thinks, but it’s a lie. Anyone can see how her plan is going to turn out. She just doesn’t want to take responsibility for it, as if she has no choice.

The light changes and she goes straight, past the entrance of the CVS and the Stop & Shop. Beside her, unbroken for a mile, runs the fence of the airport where the planes that tow the advertising banners for Foxwoods and Narragansett and the Wilcox Tavern take off. During the summer she’s sat here in traffic with carloads of friends, and knows every restroom. Originally she’d weighed changing at the 99 Restaurant but worried that someone might see her. It’s safer to do it farther down, at the park with the tennis courts, where she can lock the door.

With the rain, she’s the only one there. The concrete floor is muddy with footprints and there’s nowhere to hang her coat. She uses the knob, securing the collar with the straps of her purse. The air’s dank, and when she pulls off her uniform tunic, a shiver ripples through her, raising goosebumps. She yanks on the top she’s brought—a form-fitting ribbed red velour he likes—plucking at the shoulders in the mirror to get it to sit right. The fluorescent lighting is flat, and she leans across the sink to redo her eyeliner and brush on lip gloss, then stands back to appraise the transformation. This week she’s second-guessed every choice of hers, and she’s relieved to see there was no need. She’s tempted to take a selfie—before and after—but just rolls up her tunic and shoves it in her purse, hauls her coat on and gets going, afraid of being late.

Back in the car she pops her last stick of gum and chews, her mouth filling with a sweet juice. She’s close now. The road is so familiar, yet everything looks strange—giant boulders and dead rhododendrons on both sides, broken lobster traps for mailboxes. A decommissioned buoy sits rusting in someone’s front yard, the bottom dented like an old pot. She crests the final hill and there’s the sea in the distance, a dark line. Far offshore, a ray of sunshine slants from a gap in the clouds, bronzing the water, picking out a tiny fishing boat. As she approaches the light at Shore Road, on cue it drops to green and she coasts through. After how much it’s cost her to get here, it feels too easy.

The last half mile the land is absolutely flat, meadows edged with fallen stone walls, ponds and marshlands ringed with shaggy reeds. The pastel motels and gray-shingled guest cottages are closed, their driveways roped off. NO TURNAROUNDS, a sign anchored by a whitewashed concrete block says, as if she still could. The sidewalks are empty, only a few puffed-up gulls perched on pilings, the wind ruffling their feathers. Ahead, where the road T-bones Atlantic Avenue, a police SUV cruises through the intersection, startling her. She waits an extra second at the stop sign before turning the other way, passing a nostalgic four-sided clock showing the wrong time, and there in front of her, beyond the padlocked batting cages and go-kart track, spreads her destination, the vast asphalt parking lot of the state beach.

The lot’s shaped like a racetrack, a giant oval with the entrance at the finish. On Governor’s Bay Day, when admission’s free, she and her friends have waited hours to file through the tollbooths, inching along the guardrail, so close, sometimes getting turned away, paying extra to park in people’s yards. Today there’s no line. As she follows the road around, she’s surprised to see anyone, but there are always diehards. In the near corner, just past the last ramshackle beach bar, two RVs huddle against the dunes, then for a long stretch there’s nothing but puddles, rafts of gulls driven inland, all facing the same way. Through the breaks in the dunes she can see waves crashing, throwing up foam. Farther down the lot, this side of the bathhouse, there’s a clot of cars. Even from a distance she can tell most of them are trucks—and he’d be by himself, not with a bunch of other people.

He’s not here, Birdy thinks. Somehow the girlfriend has found out—the girlfriend whose name she hates, flinching when she hears it on TV, or worse, in church; the girlfriend she pretends not to imagine him with every weekend, at movies and parties, making out on couches, wearing earrings he’s given her. She doesn’t care where they go or what they do, as if his life apart from Birdy doesn’t matter. When Birdy thinks of her, a saving blankness overcomes her. Even now Birdy’s face is changing, pinched with the effort of erasing her. Birdy doesn’t want to take her place, Birdy wants her to have never existed. The idea that she’s had Myles to herself for three years is paralyzing, a mistake Birdy likes to think he’s too nice to fix. She’d hoped today was going to be a big step for both of them, so why, turning in at the tollbooths, as she spies his Eclipse alone on the far side of the bathhouse, does her stomach drop?

Is she late? How long has he been waiting for her?

It’s all she’s wanted, to be with him, but now it feels criminal, like a drug deal. Cutting across the empty spaces, she fumbles with her phone, holding down the button to turn it off, the screen finally going black. She spits her gum into a tissue, shoves the wad in the ashtray, getting rid of the evidence.

As she pulls up beside him, he steps out, popping open an umbrella, and comes around to shield her from the rain, just like in the song. He offers his hand as if asking her to dance. She takes it and steps out into the wind and cold, the ocean thundering beyond the dunes, and before she can say a word, he kisses her, his mouth hot, his body hard against hers, and she forgets everything else. They’re totally exposed, their cars, their license plates. Somewhere someone’s watching them on surveillance cameras, but she doesn’t care.

“I missed you,” he says.

“I missed you,” she says, and kisses him again, greedily, like the first wasn’t enough.

“Come on.” He opens the door for her and she ducks in, the warmth and the scent of his cherry vanilla air freshener enveloping her. She watches him circle the hood, then, as if they’ve been married for years, reaches across the driver’s seat for the handle and opens his door for him.