Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

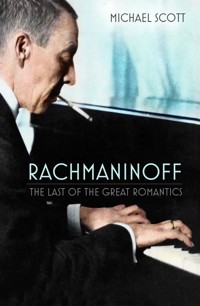

The musical child of Russia's golden age, Sergei Rachmaninoff, was the last of the great Romantics. Scorned by the musical establishment until very recently, his music received hostile reviews from critics and other composers. Conversely, it never failed to find widespread popular acclaim, and today he is one of the most popular composers of all time. Biographer Michael Scott investigates Rachmaninoff's intense and often melodramatic life, following him from imperial Russia to his years of exile as a wandering virtuoso and his death in Beverly Hills during the Second World War, worn out by his punishing schedule. In this remarkable biography which relates the man to his music, Michael Scott tells the colourful story of a life that spanned two centuries and two continents. His original research from the Russian archives, so long closed to writers from the West, brings us closer to the spirit of a man who genuinely believed that music could be both good and popular, a belief that is now triumphantly vindicated.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 470

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

RACHMANINOFF

For Michael and Pamela Hartnall

First published 2008

This paperback edition first published 2023

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Michael Scott, 2008, 2023

Front cover image © Library of Congress

The right of Michael Scott to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

isbn 978 0 75247 242 3

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ Books Limited, Padstow, Cornwall.

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

Contents

Acknowledgements

Preface

1 1873–1885

2 1885–1889

3 1889–1893

4 1892–1897

5 1897–1902

6 1902–1906

7 1906–1909

8 1909–1911

9 1912–1914

10 1914–1917

11 1917–1920

12 1920–1924

13 1924–1927

14 1927–1930

15 1930–1932

16 1932–1936

17 1937–1939

18 1939–1943

Notes

Bibliography

Music, like poetry, is a passion and problem

Sergei Rachmaninoff

Acknowledgements

I should particularly like to thank many friends over the years who have generously helped me in countless different ways: Michael Aspinall of Naples who has given me the benefit of his erudition and knowledge; Gregor Benko of New York who has been unstinting in his efforts to secure information; the late Richard Bebb and his peerless collection of recordings and memorabilia; Jack Buckley; Peter G. Davis of New York Magazine; Nicholas Hamer of Mauritius for his unstinting generosity and exceptional patience; Michael and Pamela Hartnall; Stephen Hastings, Editor of Musica; the late Jack Henderson who went to Rachmaninoff recitals; the late Joel Honig; Francesco Izzo; the late Frank Johnson, Editor of The Spectator; Vivian Liff; Bert Luccarelli; Guthrie Luke, pupil of Alfred Cortot; Barrie Martyn, author of Rachmaninoff: Composer, Pianist, Conductor, and his wife Alice, who graciously invited me to their home before we had even met; Liz Measures; Andy Miller and Karen Christenfeld of Rome; Joel Pritkin who sent me photographs of Rachmaninoff’s last Californian residence; the late Patric Schmidt of Opera Rara; Randolph Mickelson who entertained me at his homes in Venice and New York; Mary Tzambiras; John Ransley; my brother John and sister-in-law Coby who invited me to Riga; my sister Edith and brother-in-law Philip; Robert and Jill Slotover; Robert Tuggle, Archivist of the Metropolitan Opera, New York; the late Professor L.J. Wathen of Houston; Raymond A. White of the Library of Congress, Washington; and last, but not least, to Robert Dudley. I am also grateful to Christopher Feeney, Jim Crawley, Sophie Bradshaw and Kai Tabacek of The History Press.

I have transliterated Rachmaninoff the way he did himself, that is in the French style, as I have done with Chaliapin, Diaghileff, Baklanoff and Tchaikovsky. With other names I have preferred familiar spellings. Inevitably this has led to inconsistencies, but then English is irregular and systems are inapplicable.

Preface

Rachmaninoff was the last in the tradition of the great romantic composer pianists that had developed through the nineteenth century, from the days of Chopin and Liszt. By his time, the increasing complexity of music had led to a growth in the size and importance of the orchestra which demanded another new type of virtuoso: the conductor. Whereas before the revolution in Russia Rachmaninoff was well known as a conductor, after it, exiled in the west, he turned to the piano and to composing, and hardly ever conducted. Another, from our point of view today, more revealing respect in which he differed from his predecessors is that he lived into the age of recordings, and as well as his music we now also have records of him as a pianist and conductor. They have something interesting to tell us, not only about his own compositions, but they are hardly less illuminating for the light they throw on the interpretation of romantic music generally.

By the First World War, even in a society as reactionary as imperial Russia, his compositions reflected a musical style that had already become passé. His records shed light not only on his own compositions, but on the interpretation of romantic music generally. There is a paradox contained in the fact that although critics sniffed at his compositions, especially after he moved to America and western Europe, the public continued to admire them inordinately. It is revealing that notwithstanding the Depression, the concerted works he played were almost always his own compositions.1

Today, more than sixty years have passed since his death and his music has become a part of the concert repertory; his reputation as a composer has been restored. In 1918 when he began his career as a piano virtuoso, aside from his own compositions, his repertory was of the narrowest kind. He played only a few token works from the classical period (often arrangements or paraphrases) and rarely played anything more modern than the works of Scriabin and Medtner. Looking over his concert programmes today, much in them may seem insubstantial or over-familiar. We might feel tempted to accuse him of cynicism – or of having his eye on the box-office. There was no need for him to adapt his playing, as every pianist must today, to the many divergent musical styles that are now available.

As soon as he touches the keys he immediately establishes his own personality, yet he does not obfuscate by imposing himself on the music; rather, he illuminates. His performance style comes in marked contrast to what we may expect, thinking of his music; his records will certainly surprise those who confuse romantic with self-indulgent. In 1927, Olga Samaroff, herself a distinguished pianist, wrote: ‘Rachmaninoff seldom displays in my opinion the emotional warmth and sensuous colour so characteristic of his own creative muse.’2 By then it was not his playing but the conception of what constituted the romantic style that had changed. Romantic music was fast going out of fashion, its style becoming decadent. For Rachmaninoff, the popular romantic classics were neither exhausted by the incessant replay that electric media has exposed them to, nor alienated by the introduction of a new, unsympathetic post-romantic style. Recordings of him conducting and playing the piano remind us how illogical it is to believe that a period so rich in the creation of great masterpieces did not know how to interpret its own music.

They reveal two telling aspects of his technique: his command of dynamics and his rhythmic control. In the last three-quarters of a century, just as amplification has gradually corrupted our appreciation of dynamics, so the overwhelming influence of Afro-American jazz has introduced a narrower, more literal sense of rhythm. His records remind us that virtuosity is not just a question of not playing any wrong notes but of playing the right ones in the right places.

One no sooner reflects that perhaps the most fabulous aspects of his piano playing were his melodic eloquence and dramatic virtuosity, than one remembers the unique rhythmic bite in sustained, short or syncopated accentuation, or his way of orchestrating chords with special beauty through individual distributions of balances and blendings.3 He use[d] the pedal dexterously in his production of light and shade … he [did] not abuse this device; indeed he [wa]s often austere in the niceness with which by a perfection of timing, he released the sustaining pedal to avoid dissonance.4

In 1939 he recorded his First Piano Concerto. There can be no more fitting word for his playing in the cadenza towards the end of the first movement than Olympian. What is remarkable is his ability to organise it without the discipline of bar lines. Spontaneously he reconciles the details within his overall conception, yet he plays it without any sense of artifice or contrivance. The underlying rhythmic certainty dominating his conceptions cannot be notated, and in such a fashion he demonstrates what makes romantic music so effective. As time marches on through new musical territory, how grateful we are to possess his recordings. It has taken until the age of the CD, and of modern remastering techniques, for RCA to reissue them all in high fidelity. There are more of Rachmaninoff’s recordings on sale today than have ever been available before, even during his lifetime.5

1

1873–1885

The Rachmaninoff family’s aristocratic origins: Born twelve years after the emancipation of the serfs: Changed political circumstances enable him to become a musician: Secures place at St Petersburg Conservatory but fails examination: Cousin Siloti secures opportunity for him at Moscow Conservatory.

Sergei Rachmaninoff was born on 20 March 18731 at Semyonovo, one of his family’s estates to the south of Lake Ilmen in the Staraya Russa region. ‘It was near enough to ancient Novgorod to catch the echoes of its old bells’,2 or so he would like to remember years later when his childhood memories were particularly dear to him. By then, this world had long been swept away. Oscar von Riesemann paints a word picture of an estate like the Rachmaninoffs at the time of his birth:

The manor-house was a low one or two storied wooden structure, built with logs from its own forests, whose sun-mottled gloom reached up to the garden gate; roomy verandas and balconies stretched around the whole front of the house, which was overgrown with Virginia creeper; behind lay stables and dog-kennels that housed yelping Borzoi puppies; in front of the house was a lawn, round in shape – with a sundial in the centre – and encircled by the drive; a garden with gigantic oaks and lime trees, which cast shadows over a croquet lawn, led into a closed thicket; a staff of devoted servants who, under good treatment, showed an unrivalled eagerness to serve, made house and yard lively.3

However, Riesemann’s eloquence should not disguise the fact that life in Russia in those days had another side to it, and that the Rachmaninoffs were among the privileged minority. As in France in the days of Louis XVI, or in the United Kingdom at the time of the Industrial Revolution, the vast majority was illiterate, many half-starved, and disease rampant.

According to a genealogy, ‘Historical Information About the Rachmaninoff Family’,4 it could be traced back to the days of Mongolian domination in the Middle Ages. As photographs taken in the last years of Rachmaninoff’s life suggest, there is something almost Mongolian-looking about his features – his almond-shaped eyes with heavy bags under them, his pendulous lips. Stefan IV, one of the rulers of Moldavia, had a daughter, Elena, who married the eldest son and heir of Ivan III, the Grand Duke of Moscow. Elena’s brother accompanied her to Moscow and it was his son, Vassily (nicknamed Rachmanin) from whose line the composer’s family may be traced. The name has its origins in an Old Russian word, ‘rachmany’, meaning hospitable, generous, a spendthrift. As we shall see, Rachmaninoff’s father was all of these things.

In the eighteenth century, Gerasim Rachmaninoff, the composer’s great-great-grandfather, was a Guard’s Officer in one of the Romanoff family’s many succession disputes. When Elisabeth, Peter the Great’s daughter, became Tsaritsa he was rewarded with an estate in the district of Tambov at Znameskoye. It lies in the steppes, one of the most fertile parts of Russia, situated to the southeast of Moscow. The family remained here for the next 150 years. Alexander Gerasimovich, Rachmaninoff’s great-grandfather, was a competent violinist and his wife was related to Nicolai Bakhmetev, a minor composer in the Imperial Chapel. Given how large Russia was and how poor communications were, families were obliged to make music for themselves in those days. Alexander’s son, Arkady, joined the army but retired after duty in one of the many Russo-Turkish disputes. Arkady took piano lessons from John Field, the Irish virtuoso, but by the time Field came to Russia he was in the late stages of alcoholism and his powers were in obvious decline. Mikhail Glinka, the first important Russian composer, studied with Field and wrote of his playing, ‘His fingers were like great drops of rain falling on the keys as pearls on velvet.’5

The only time Sergei met his grandfather was as a boy, but the memory of the occasion remained with him for more than half a century. ‘I played my little tunes, consisting of four or five notes and he added a beautiful and most complicated accompaniment.’6 Arkady played music at the homes of other members of the nobility and although he never pursued professional standards – as a member of the landowning class it was not necessary – a quantity of his waltzes, polkas and other salon compositions did get into print. He is the only other member of the Rachmaninoff family to merit even a footnote in history. Princess Golizin, in her memoirs,7 recalls how as soon as he got up every morning he would go straight to the piano and let nothing distract him while he practised for four or five hours. His family was large (there were nine children) and the sons were all required to follow in their father’s footsteps and join the army.

Vasily, Rachmaninoff’s father, joined the Imperial Guards in 1857 at the age of 16. For the next couple of years he was sent off to the Caucasus to suppress a nationalist uprising by the Muslim leader, Imam Shamil. In 1862 he took part in the suppression of the Polish nationalists and thereafter spent his time in a typical fashion – drinking, gambling and making love. After nine years’ military service he made a coup of his own by marrying Lyubov, the daughter and heiress of General Butakov, the head of the Araktcheyev Military College. Vassily quit the army to lead a princely life in the manner of his forebears. Like his father, Arkady, he too showed musical talent. His daughter Varvara recalls how ‘he spent hours playing the piano, not the well-known pieces, but something – God knows what, and I would listen to him to the end’.8 Years later in his recitals, Rachmaninoff would often programme a piece based on a theme he remembered his father playing, supposing it to have been written by him, Polka de W.R. (a French transliteration of his initials), but it was in fact the work of a prolific Austrian composer, Franz Behr, in the Johann Strauss mould.

Vasily Rachmaninoff’s family consisted of three daughters (Elena, Sophia and Varvara) and three sons (Vladimir, Sergei and Arkady). Sergei was raised in the traditional manner by a nurse, and took lessons from private tutors. His mother introduced him to music and he was only 4 years old when she first sat him at the piano. Like members of his father’s family, he showed an aptitude for music from an early age but it seems unlikely that his talent would ever have amounted to much without his mother. The part his mother played in securing his first piano teacher is recalled in a letter written years later to Rachmaninoff by Mlle Defert, his sisters’ Swiss governess:

You may recall how your mother enjoyed accompanying my singing. Do you remember how you stayed at home one day under the pretext of not feeling well, so I was obliged to stay with you? When we were alone you surprised me suggesting I sing a song your mother often accompanied me in. How astonished I was to hear your small hands play chords that may not have been complete but were without a single wrong note. You made me sing Schubert’s ‘Mädchenklage’ three times. I told your mother that evening. The next day the news was sent your grandfather General Butakov and he ordered your father to go to St Petersburg and bring back a good piano teacher.9

As a result, Anna Ornatskaya, a young graduate of St Petersburg Conservatory, was engaged to give Sergei his first piano lessons.

Like his father, grandfather and great-grandfather, Rachmaninoff’s social position precluded his making a career as a professional musician and it was ordained that he would join the corps des pages of the Guards. However, it did not take long before economic changes in Russia began to affect the Rachmaninoffs. From his father’s youth his wealth had caused him to court pretty well every attractive woman he met, but that had not contributed to making him provident. In the first years of his marriage the income from his estates had proved more than enough to cope with, even with his profligacy; but soon there was no place left for the extravagant, often absentee, landlords of old Russia. The rapid progress of industrialisation in western Europe inevitably led to the collapse of feudal Russia: In 1861 the serfs were emancipated and for the landowners this necessitated a new and revolutionary husbanding of their resources.

By 1877, only five years after his wealthy father-in-law’s death, Vassily had managed to squander his wife’s entire inheritance. At first Lyubov’s position had been little different from the heiresses of previous generations; so long as their husbands could manage their estates competently then they had to put up with their philandering. But Vassily became bankrupt and Lyubov was faced with the prospect of having to fend for herself. She had no mind to play the role of her namesake in Chekhov’s play and sit back while the cherry orchard was taken from her. The furious rows resulting from the genteel poverty that the Rachmaninoffs were slipping into, led to Sergei’s parents separating. Lyubov moved to St Petersburg with all of the children, where her mother, Sophie Butakova, joined her. Sergei who was only ten could not have understood much of what was going on; all he knew was that his father loved him very much. He thought him kind and generous, but his mother was aware of the importance of introducing orderliness into family life. Rachmaninoff remembers her years afterwards stating ‘there should be a time for everything’.10

Soon after their arrival in Russia’s capital, one of Vassily’s married sisters, Maria Trubnikova, agreed to take Sergei into her family until Lyubov was settled. The Trubnikovs nicknamed him ‘yasam’ (myself); so independent was the little lad that when anyone in the family offered to help him he would brush them aside insisting ‘yasam’. No sooner were they settled in St Petersburg than a diphtheria epidemic broke out. Three of the Rachmaninoff children contracted it, and although Sergei and his elder brother Vladimir both recovered, their sister Sophia died. Sergei’s maternal grandmother helped to support the young Rachmaninoffs during these difficult years and it was she to whom the boy felt particularly close. Sergei enjoyed the summer vacations he spent with her at Borisovo, near the familiar landscape of Oneg, one of the family estates his father had been obliged to sell. He would wait impatiently for her to take him to church, where he would listen attentively to the music. Then, as soon as they were home again, he would go straight to the piano, and with his feet scarcely reaching the pedals, play through the chants he had heard. Although not conventionally religious, a preoccupation with Russian church music would remain an important influence on Rachmaninoff’s compositions throughout his life.

It was during these summers that we first glimpse the composer. After dinner, the boy would improvise at the keyboard in front of his grandmother’s guests, although he always claimed he was playing pieces by Beethoven, Mendelssohn and Chopin. After these impromptu recitals, he recalled, ‘she never failed to reward me with twenty-five kopeks, and naturally, I was not loathe to exert my memory, for such a consideration meant a large sum to a lad of ten or eleven.’11 His surviving elder sister, Elena, who was more than five years his senior, had a love of music which made for a common bond. She had a fine contralto voice with a natural individuality of timbre that foretold a great future. Sergei loved to accompany her. She would sing the latest fashionable song, like Tchaikovsky’s ‘None but the lonely heart’. Sometimes he was so deeply affected that he proved unable to finish, and she had to push him off the piano stool and accompany herself. In the autumn of 1885, when she was eighteen and had secured an engagement at the Bolshoi, Elena died suddenly. This was a traumatic event for the twelve-year-old Sergei.

The family’s straitened circumstances made a place in the Guards impossible and Vladimir, Vassily’s eldest son, had to go to an ordinary military academy. This, combined with the boy’s obvious talent, made a career in music seem possible for Sergei. With the recommendation of Ornatskaya he gained a scholarship for the St Petersburg Conservatory. The fact that he had a perfect ear and could name almost every note in the most complicated of musical structures, persuaded his teachers that he had no need for basic theoretical training. Like many with exceptional talents, he did not fit easily into the conservatory regime and was allowed to go straight into harmony classes with older, more mature students. It was not until after failing his examinations that leading questions were asked him and his incompetence became obvious. At length, Karl Davydov, Principal of the Conservatory, complained to Lyubov, but she had no idea what to do. It was in 1885 that Lyubov’s nephew, the young pianist Alexander Siloti, returned home after completing his studies to accept an engagement at the Moscow Conservatory. Having spent three years with Liszt and created a considerable sensation in concert, Lyubov begged Siloti to hear Sergei and give her his opinion of the boy’s worth. Before doing so, however, Siloti happened to meet Davydov and asked him what he thought of Sergei. Davydov pulled a long face and replied that he could see no point in the boy continuing studying. It was with some difficulty that Lyubov finally managed to persuade Siloti to come to the Rachmaninoffs’ apartment and hear his cousin play, but he was at once impressed. He told Lyubov that Sergei was very talented but that he needed stringent discipline. He recommended that she enrol him at the Moscow Conservatory and put him under the rigorous tutelage of Nicolai Zverev, his old teacher.

2

1885–1889

Rachmaninoff’s most important piano teacher: Life at Zverev’s: Joins Moscow Conservatory, staff includes Arensky, Taneyev and his cousin Siloti: Meets composers Rubinstein and Tchaikovsky: Begins to compose: Sudden departure from Zverev’s.

In 1885 Nicolai Zverev was fifty-three. He had studied piano with two leading teachers, the Frenchman Alexandre Dubuque and the Bavarian Adolf von Henselt, both of whom spent many years in Russia. Dubuque, like Rachmaninoff’s grandfather, had lessons with Field and taught Alexander Villoing, who numbered among his pupils the Rubinstein brothers, the virtuoso Anton, the pedagogue Nicolai and the composer Balakirev. At the time of its composition Balakirev’s ‘Islamey’ was rated the ne plus ultra of virtuosity. Although Balakirev was not noted for his modesty he is on record as stating: ‘If I can play the piano at all, it is entirely due to ten lessons I had with Dubuque’.1 Henselt rarely gave concerts and spent most of his time teaching. He told the American pianist Bettina Walker, who studied with him in his later years, ‘I have never ceased wrestling and fighting with the flesh.’2 Walker was a devoted pupil yet she cannot forebear from recalling how the soubriquet ‘Henselt-kills’3 stuck to him. Like Henselt, Zverev was devoted to practice, but whereas Henselt did not need much coaxing to be persuaded to play, Zverev hardly ever touched the piano, even in front of his students. Rachmaninoff never heard him play. Older pupils, like Siloti, remembered ‘a very elegant and musical pianist with an unusually beautiful tone’,4 especially the remarkable effect he created playing Beethoven’s Moonlight Sonata.

In his affluent youth Zverev conceived his piano studies as no more than finishing lessons for a gentleman. However, like the Rachmaninoffs, his landowning family fell on hard times as was so often the way in the then rapidly changing Russia. At the age of thirty-five, less than a decade after the emancipation of the serfs, he was obliged to sell the family estate. It was then that he chanced to encounter Dubuque. When Zverev told Dubuque that the only living he could expect to find was that of a civil servant, Dubuque replied: ‘Then you had better stay here and I’ll get you piano lessons,’5 and that he did. In only a few years Zverev became one of Moscow’s leading teachers and by 1900 no less than twelve out of nineteen of the Moscow Conservatory’s gold medallists had been his pupils, and many became professors. Zverev’s career proves a Shavian axiom: ‘If you can, do; if you can’t, teach; if you can’t teach, then teach teachers.’

At Dubuque’s apartment Zverev met Tchaikovsky and the composer agreed to give him lessons in musical theory. As Tchaikovsky’s diaries confirm, they soon became friends and he even dedicated a song to him: Distant Past (Op. 72 No. 17). In 1870 Nicolai Rubinstein, the founder of the Moscow Conservatory, appointed Zverev teacher of junior piano students. In the mornings, he would teach privately at home for two hours before departing for the Conservatory at ten o’clock. After a break for lunch he would resume teaching, but this time he would take a carriage round to the homes of the wealthy and fashionable giving lessons, sometimes until 10 p.m., and for more than appreciable sums. What he earned from his demanding labours was sufficient to satisfy his need for creature comforts, and it enabled him to accommodate a trio of the youngest and brightest conservatory scholarship boys in his home where they received tuition for free.

After hearing Sergei dispatch one of Reinecke’s studies, Zverev immediately accepted him. At the time he had just lost one of his ‘cubs’, as he called them, and had room for another. Already studying with him were Matvei Pressman, three years older than Sergei, and Leonid Maximov, his contemporary. Pressman became director of the Conservatory at Rostov, while Maximov died in 1904 of typhoid. Zverev ran his students’ lives in martinet fashion, supervising every minute of their time; his regime included a six day week for the whole year and they had no vacations. They shared a bedroom in which there was a piano. They would rise at six in the morning and take it in turns to start practising right away, irrespective of whether they had been out late with Zverev the previous night. If they had, they might play fistfuls of wrong notes. On such occasions Zverev, hung-over though he may have been, would storm in clad only in his night clothes and make cutting remarks and slap them hard. In such fashion he would literally afford them a taste of his famous loose-wrists technique.

Pressman discussed Zverev’s method: ‘An extremely valuable feature of his teaching was that he introduced us to music from the very beginning. To play unrhythmically, or without observing musical grammar and punctuation, was not tolerated and that, of course, is the whole basis of music, upon which it is not difficult to build even the biggest artistic structure.’6 In later years Rachmaninoff remembered Zverev affectionately:

He treated us as if we were his equals. Never, under any circumstances, did he let us want for anything. Our clothes were ordered from the most expensive tailor in town, the same who supplied his. There was no first night, no interesting or outstanding performance; no opera which we did not attend. We saw many performances given by famous theatre stars. I had the good fortune to see great actors like Tommaso Salvini, Ludwig Barnay and Eleonora Duse.7

During Sergei’s first years of study, partly at the Conservatory with Siloti and partly with Zverev, his progress was rapid. At the beginning of his second year he won a Rubinstein scholarship, and thereafter appeared frequently at student concerts. As the programmes show in 1885 he played Bach’s English Suite in A minor (BWV 817); he would play this at his last recital fifty-eight years later. In 1886, he played Henselt’s Study in D (Op. 5) and in 1887, the second and third movement of Beethoven’s Sonata in E flat (Op. 31 No. 3). On other occasions he played pieces by Moszkowski and Schulhoff, a pupil of Chopin. When the boys were not at the conservatory, they would be at home practising under the beady eye of Zverev’s spinster sister, Anna Sergeyevna, ‘a rather disagreeable and spiteful person,’8 as Rachmaninoff described her. She would carry out her brother’s instructions and see that the boys were not late to start practicing or early to finish. Although Zverev was not concerned with the study of theory and harmony – these were of greater importance to composers than pianists – he did employ a teacher, Mme Belopolskaya, who would play four-hand arrangements with the boys in turn. Back then, before the existence of the radio or record player, Zverev was concerned that his pupils should acquire a complete musical background as well as become familiar with the new repertory being written, whether chamber music, symphonic or orchestral works.

On Sunday mornings Zverev would give lessons to other talented but poor students. Included amongst them was, as Rachmaninoff recalled, ‘a little cadet from the Moscow Military College, who was about my own age, it was Alexander Scriabin.’9 On Sunday afternoons and evenings it was Zverev’s habit to keep open house at which the guest list would read like a Russian musical who’s who. It might include: Anton Arensky, the composer and teacher at the Moscow Conservatory; Anton Rubinstein; Siloti; Sergei Taneyev, another composer and teacher who was also the director of the Moscow Conservatory and his successor, the conductor Vasily Safonov; Tchaikovsky and his brother librettist Modest; the baritones Joachim Tartakov and Leonid Yakovlev. The boys would be called in to play a Mozart sonata, a piece of Mendelssohn’s or a Cramer study. When they had finished Zverev would turn to his guests smiling and say ‘“See, that’s the way to play the piano!”’ His concern was that these events should advertise his pedagogic skill. ‘He would not seem perturbed,’ Pressman later recalled, ‘that same morning, after hearing one of them play the same piece he had growled – “Is that the way to play the piano? No! Get out.”’10

In January and February 1886, Rubinstein played his seven Historical Recitals at Moscow’s Nobility Hall on successive Tuesday evenings, and repeated them on Wednesday mornings for non-paying student audiences. Zverev took his cubs to these performances. They were events of the first magnitude since critical opinion rated Rubinstein, after Liszt, the greatest pianist of the day. He presented a complete survey of works, beginning with the English virginalists Byrd and Bull, then Bach, Couperin and Scarlatti, continuing with Mozart, Beethoven and Chopin up to Liszt, and finishing with the Russian moderns. As a pianist, Rubinstein’s catholicity was complete. In the variety and breadth of his musicianship he was a typical nineteenth-century figure and may be compared with Goethe: a great literary genius who had been deemed to know about everything from literature and the arts to philosophy and even science – it was still possible in those days. Certainly no pianist before Rubinstein, not even Liszt, attempted as comprehensive a repertory. An equivalent accomplishment today would be impossible, not only because most tastes do not care for Byrd and Bull on the piano, but because the century since Rubinstein has accumulated music of such widely divergent technical demands that no one pianist, no matter how virtuosic, could attempt to embrace so exhaustive a repertory with equal stylistic authority.

Rubinstein’s playing had a mesmeric effect on the Zverev boys. Pressman never forgot him:

He enthralled you by his power; he captivated you with the grace and elegance of his playing, with his tempestuous, fiery temperament and by his warmth and charm. His crescendo seemed to have no limits to the growth of the power of its sonority; his diminuendo would modulate to the merest pianissimo, yet it would still project surely even in the farthest reaches of the biggest hall. In his playing Rubinstein created, and created inimitably and with genius.11

Zverev gave a dinner party in honour of Rubinstein. Sergei remembered ‘being chosen to lead the guest of honour in, by the coat-tails, for he was almost blind by then. Someone asked him Rubinstein about a young pianist [probably Eugen d’Albert] wanting to know how he liked his playing. Rubinstein thought for a moment and shrugged: “Oh, nowadays everybody plays well”.’12

At one of Rubinstein’s recitals, when he was playing Balakirev’s ‘Islamey’, Sergei recalled:

Something distracted him and he apparently forgot the composition entirely, but kept improvising in the style of the piece, then after a few minutes the remainder of the composition came back to him and he played it through to the end correctly. However this annoyed him so greatly that although he played the next piece on the programme [Tchaikovsky’s Song without Words, Op. 2 No. 3] with the greatest exactitude, strange to say, it had not the wonderful charm of the interpretation of the piece in which his memory failed. Rubinstein was really incomparable, just because he was so full of human impulse and his playing very far removed from just mechanical perfection.13

This spontaneity and apparent lack of premeditation in Rubinstein’s playing fits in with Rachmaninoff’s account of another incident at another of these recitals when he repeated a passage in the third movement of Chopin’s Sonata in B flat minor (Op. 35): ‘Perhaps because he had not succeeded in the short crescendo at the close as he would have wished. I could have listened to this passage over and over again.’14 It is not surprising that Rubinstein’s playing of this piece should have left an indelible impression on Rachmaninoff and in later years he would often programme it in concerts he gave. Eduard Hanslick, the noted Viennese critic, has left a description of Rubinstein’s playing: ‘The mighty crescendo at the beginning of the trio in the Funeral March, and the gradual decrescendo after it, was a brilliant innovation of his own.’15 As can be heard on Rachmaninoff’s 1929 recording, he plays it in the same fashion.

Rachmaninoff’s affection for Rubinstein’s piano playing remained with him all his life, which may perhaps seem strange for although recorded evidence, as well as countless ear-witnesses, confirm that his playing was ‘full of human impulse’, no pianist rehearsed more assiduously or was more thoroughly prepared. Rachmaninoff’s interpretations (though not his compositions) represent the epitome of what today could be called the classical style. As his records demonstrate that, ‘His rubato consists of subtle adjustment of rhythmic detail, rather than the languishing mini-rallentando that tends to characterize the rubato of later pianists in Romantic music. As a result, his rubato does not hold up the flow.’16 His playing has much of the rhythmic vitality and dynamic grandeur that so strongly impressed him in Rubinstein’s. By the time Rachmaninoff’s international career as a concert pianist began after the First World War, the growing population in the western world was becoming ever more prosperous. The popularity of the radio and the record player led to the increasing exposure of the standard repertory of classics and, inevitably, to the public’s greater familiarity with it. This encouraged pianists – indeed, all performing musicians – to sacrifice spontaneity of execution to textual accuracy.

An interesting comparison may be made between recordings by Rachmaninoff and his contemporary Josef Hoffmann, the Polish pianist and Rubinstein’s only private pupil. Hoffmann always spoke of Rachmaninoff as the greatest pianist of the day and so Rachmaninoff spoke of Hoffmann. Although Rachmaninoff left a considerable number of recordings, none is of a live performance. Hoffmann on the other hand made a much smaller selection of (often unrevealing) recordings, but a lot of live performances survive17 and these show much of Rubinstein’s spontaneity. Rachmaninoff is in the tradition of many great musicians – Chaliapin, Kreisler, Cortot and Callas – in that over the years his interpretations hardly change. Compare different recordings he made of the Polka de W.R. in 1919, 1921 and 1928, for example. Yet Hoffmann, as we hear in two live recordings of Chopin’s Andante Spianato made only months apart,18 could be interpretatively (though not technically) two different pianists. It is not difficult to believe that there is in Hoffmann’s playing – in its exquisite finish and seeming weightlessness of tone, coruscating virtuosity and prodigious dynamic range – something of the temper of Rubinstein, as well as some of those wrong notes!

In the summer of 1886 Zverev took Sergei, with Maximov and Pressman, to the Crimea. He often went there in the summer, so as to give piano lessons to the children of the millionaire Tokmakov. He would rent a house nearby, ‘but it was not to be a carefree vacation for his boys – that would not be consistent with his programme.’19 With them went Nicolai Ladukhin, Professor of Harmony, who gave the boys a crash course ‘in two and a half months, what would according to the conservatory curriculum, take two to three years to accomplish’.20 This was Zverev’s way of preparing them for the following year. They would quickly pass the theory and basic harmony examination and could soon begin more advanced work. The effect on Sergei was immediate. Pressman remembered how he began for the first time to compose:

I remember how pensive and silent he grew, walking around, his head lowered, his eyes fixed on some distant point. This state lasted for several days. Finally, and somewhat mysteriously, choosing a moment when no one else was about, he beckoned me to the piano and began to play. ‘Do you know what that was?’ he asked. ‘No’ I replied ‘I don’t.’ ‘I composed it myself, and I dedicate it to you.’21

Unfortunately no trace of the piece, a study in F sharp, has survived.

Back in Moscow at the Conservatory, Tchaikovsky was present at the opening ceremony before the new term. He had been Professor of Theory and History until 1878, but by this time he was 46 and remained only in an advisory capacity. He had already composed many of his more famous works and it seems likely that most of the students present took more notice of him than he of them. Rachmaninoff already admired Tchaikovsky’s music inordinately. Tchaikovsky’s diary account of the event is cursory: ‘Dedication service at the Conservatory. Reading of the report. Professor Nicolai Kashkin’s speech on Liszt [who had died that summer] was endless.’22 It was at this time that Sergei was first able to apply some of the fruits of his studies in theory and harmony when, in a gesture of respect and admiration, he produced a four-hand arrangement of Tchaikovsky’s Manfred symphony, a work that had first been heard the previous spring. He and Pressman played it when Tchaikovsky came to one of Zverev’s Sunday evenings. In the last movement there occurs a reference to the plainchant Dies irae and this, although Sergei was only 13 years old, was to become almost a signature tune. Tchaikovsky’s diary, not a wordy document as we noted, mentions ‘a supper at Patrikeyev’s restaurant at which, with a number of others Zverev and his pupils had been present’.23 On this occasion, as Tchaikovsky came in, the salon de thé ensemble got to its feet and struck up a waltz from one of his ballets. Rachmaninoff remembered him commenting: ‘When I was young it was the dream of my life to think that some day my music would be so popular that I would be able to hear it played in restaurants. Now I am quite indifferent.’24

On Zverev’s fifty-fifth birthday, 13 March 1887, his cubs had organised a surprise. After morning coffee they led him into the drawing room and played their birthday pieces. Sergei began with Tchaikovsky’s Troika from The Seasons (Op. 37b), which he recorded three times and was still including in recitals more than half a century later. Pressman played The Snowdrop, also from The Seasons, and Maximov played a nocturne of Borodin’s. ‘Nothing could have given Zverev more pleasure,’ Pressman remembered. ‘At his formal birthday dinner that night Zverev boasted of the musical gifts he had received and made us sit down at the piano and show off to the guests. Everyone was pleased and Tchaikovsky kissed all of us.’25 The stimulus offered by Tchaikovsky’s music encouraged Sergei to start to compose. Three of his piano solos, Nocturnes, are dated between November 1887 and January 1888 and reveal a considerable advance, both musically and stylistically, on his earliest surviving piano solo, the Song Without Words. The latter was written as an exercise for Arensky’s harmony class at the end of the 1886/87 academic year and years later Rachmaninoff wrote it out from memory for inclusion in Riesemann’s Rachmaninoff’s Recollections. Another piece of juvenilia, the Scherzo in D minor for orchestra, is dated 5–21 February 1888 although the date on this has been altered at some stage to 1887, ‘which improbably places the work only two or three months after Rachmaninoff’s initiation into the mysteries of orchestration’.26

Tchaikovsky’s influence on Rachmaninoff’s music is obvious enough but his two conservatory teachers – Arensky who taught him harmony, fugue and free composition, and Taneyev, from whom he learned counterpoint – were scarcely less important. Arensky, who was only a dozen years older than Rachmaninoff, wrote many compositions, many of them charming if slight, including a Suite for two pianos, a piece entitled Silhouettes and Variations on a Theme of Tchaikovsky, which Rachmaninoff would later conduct with the Moscow Philharmonic Orchestra.27 Although a Rimsky-Korsakov pupil, that did not prevent his master dismissing him:28 ‘he will soon be forgotten,’ he asserted. This may have been an oblique reference to Arensky’s alcoholism which brought his career (and life) to an untimely premature conclusion, or maybe Rimsky was jealous because Arensky ‘had fallen under Tchaikovsky’s influence’.

Taneyev, five years older than Arensky, was at that time director of the Moscow Conservatory, where he had studied with Nicolai Rubinstein and Tchaikovsky. Rimsky-Korsakov described his music as ‘mostly dry and laboured,’29 although he admitted to finding an opera, The Oresteia, ‘striking in its wealth of beauty and expressiveness’.30 Unfortunately little of it is heard today, even on the fringes of the repertory. Taneyev and Rachmaninoff kept in regular contact and it was only months before Taneyev’s death in 1915 that Rachmaninoff took his All-Night Vigil for him to look over before it was published. If Arensky’s music reinforced the influence of Tchaikovsky on Rachmaninoff then it was Taneyev – the man – who had the more profound effect on him, as we shall see from the lengthy obituary Rachmaninoff wrote for Russkiye Vedomositi.

Immediately before the summer vacation in May 1888, an opportunity arose for Sergei. In the next year there was to be a division between general theory and special theory classes, the first was for interpreters and the second for creators. Tchaikovsky was on the examining board. Years later Rachmaninoff recalled what happened:

At the last examination of the harmony class the pupils were separated and given two problems to be solved without the help of a piano. The first was to harmonize a melody in four parts [I think the theme was Haydn’s]. The second was to write a prelude of sixteen to thirty bars, in a given key and with a specified modulation, to include both pedal points on both the dominant and tonic. When all the candidates had turned in their work I alone was left; I had got entangled in a daring modulation and could find no satisfactory solution. At last, by five o’clock, I had finished, and handed my two pages to Arensky. When he glanced at them he did not frown, so this gave me some hope. On the following day the board was to hear us play our own work. When I had finished my turn, Arensky mentioned to Tchaikovsky that I had written some pieces in ternary form for his class, and perhaps he would like to hear them. Tchaikovsky intimated his assent so I sat down and played them; I knew them by heart. When I finished I saw Tchaikovsky go over to the examination record board and write something on it. It was not for another two weeks that Arensky told me what he had written; he was probably afraid I would become vain so he had tried to keep it a secret from me. The board had granted me a ‘five plus’ [top marks], and Tchaikovsky had added three more plus signs–above it, below it and to the side of it. So my fate as a composer was, as it were, officially sealed.31

As a reward Zverev permitted him for the first time, when he was fifteen, to visit the home of his relatives, the Satins. Natalia, the elder daughter of the Satins who Sergei would marry a decade later, remembered how condescending he was to her after she played through a piano reduction of one of Vanya’s arias from Glinka’s A Life for the Tsar. This was less, we may believe, a comment on her playing or his manners, than the effect of his rigorous experience with examples in front of him like Tchaikovsky.

He spent that summer at the Crimea again with Zverev, before returning to Moscow in September. That autumn he took part in student concerts at the Conservatory playing Bach’s Prelude and Fugue in C, Rubinstein’s Study in F minor, Liszt’s Ballade in B minor and the first movement of Beethoven’s Sonata in D (Op. 28). It was at this time that the young Sergei made his first attempt to write an opera, Esmeralda, the libretto of which is based on Victor Hugo’s novel Notre Dame de Paris. Some fragments of the opera survive that are dated 17 October. In Martyn’s opinion, ‘[although] there is nothing musically significant in them, there is a surprising foretaste of maturity in the theme associated with Frollo [bass], which unmistakably looks ahead to the Prelude in G sharp minor [Op. 32 No. 12] of 1910.’32

Cooped up in the confined surroundings of Zverev’s with Pressman and Maximov incessantly practising, Sergei found it difficult to work creatively and finally plucked up sufficient courage to ask Zverev for another piano and a room where he could work alone and undisturbed. According to Riesemann, ‘his pride, confusion and excitement somehow transformed a calm conversation into a stormy argument and Zverev, losing control, raised his hand against him. Sergei by then sixteen would not tolerate such a gesture: “Don’t dare hit me!” The interview thereupon ended in a total breakdown of relations.’33 There was nothing so unusual in Zverev losing his temper and after a few days he might have forgotten the incident, only this time a whole month passed in which he never spoke to Sergei. One day he curtly ordered Sergei to meet him after classes at the Conservatory. They made their way to the home of the Satins, where Zverev told them that he did not wish to leave Sergei to fend for himself, but that it was impossible to continue living with him. He had brought him to the Satins in the hope that they would be prepared to take him in.

Another account of the severing of their relationship is rather different, however. Some years later, after Zverev was dead, Yury Sakhnovsky (with whom Sergei went to live in the autumn of 1891 when he contracted malaria) told the critic Leonid Sabaneyev that it was Sergei and not Zverev who brought their relationship to an end because Zverev was homosexual. In Russia this was a punishable offence with a maximum penalty of a dozen years’ hard labour. It is true that Zverev was unmarried, and appearing around Moscow with three boys in tow, as was his habit, would have been quite sufficient to incite rumours – even in a far more liberal society than Tsarist Russia. Not until after Zverev’s death did Sergei feel able to express himself on the subject unambiguously.

The four years in which Sergei had been living with Zverev represented a most important period of his life, when he was growing to maturity. Whatever the reason for his leaving Zverev, it is not surprising that later he would come to show many of the same distinctive personality traits so characteristic of Zverev. Rachmaninoff’s biographer Victor Seroff records:

Those who knew him [sic] noted the resemblance to Zverev, the way they carried themselves and their marked ability to keep people at a distance despite their very warm and kind natures. The shyness and awkwardness that never left him, even after he became a famous musician. In his youth his face had not been that of a young man. It was old looking, with deep creases that lent an expression of disappointment, even disapproval.34

This impression is reinforced by conservatory contemporaries such as Nicolai Avierino, who spoke of his already formed personality even at the age of only seventeen. He was self-centred but not selfish, correct and well-adjusted, and never too familiar. If sometimes he gave an impression of hauteur, and even conceit, in reality, Avierino declared, ‘this derived from shyness’.35

3

1889–1893

Moves in with the Satins: First summer at Ivanovka: Graduates from Moscow Conservatory: Finishes First Piano Concerto: Catches malaria: First appearance in public concert: Wins competition with one-act opera, Aleko: Introduces Prelude in C sharp minor.

Whichever tale is true to account for Sergei’s sudden departure from Zverev’s, he spent only a few days with his Conservatory colleague Mikhail Slonov before Varvara Satina, his father’s sister, agreed to take him in. His mother also invited him to St Petersburg, where she lived, suggesting he might move back to the Conservatory there. Although he would have liked to study piano with Rubinstein, his problem was the presence of Rimsky-Korsakov on the board of staff, which even then to a lad of only sixteen, ‘would have looked like a betrayal of Tchaikovsky and Taneyev’.1 He may not yet have been able to articulate his musical instincts, but he already identified with Taneyev and the more rigorous counterpoint style of the Moscow school rather than the new freer folk-music style of the St Petersburg School.

There are usually considered to have been two groups in the composition of Russian music in the nineteenth century. The first was led by Balakirev, and included Cui, Borodin, Moussorgsky and Rimsky-Korsakov. ‘The Big Five’, or ‘The Mighty Handful’ as they became known (a term first used in 1867 by critic Vladimir Stasov), were concerned to resist the influence of western Europe and to demonstrate their Russian quality. They were amateurs who not only had double careers (Balakirev was a railway clerk, Cui an officer in the army artillery school, Borodin, a Professor of Chemistry, Moussorgsky, a Lieutenant in the Guards and Rimsky-Korsakov a Naval officer) but resisted what they regarded as the old-fashioned academic style. However, it was not long before the youngest, Rimsky-Korsakov, became self-critical and discovered harmony, counterpoint and orchestration. In contrast to these was the second group, led by Tchaikovsky and Rubinstein, which had been influenced by music in western Europe, and with which Rachmaninoff became associated. In 1859 it was Rubinstein who founded the Russian Musical Society, in 1862 the St Petersburg Conservatory and in 1866 his brother Nicolai founded the Moscow Conservatory.

By this time Sergei must have found the freedom of life at the Satin’s a welcome change from Zverev’s. He was now sufficiently self-disciplined to be able to continue his Conservatory work unsupervised, and having a room of his own, he began a period of intense activity as a composer. In November 1889, he commenced a two piano version of a piano concerto in C minor, although abandoned it after fourteen pages. He usually began the composition of orchestral works at the piano. This was partly to do with the piano being his instrument, but in those days, with so much music being made at home, it would also have been more economically practical to have had a piano reduction published first. Before the invention of the record player, there was still a demand for two piano versions. By 1940, however, this can hardly have been the motive for completing his last new composition, Symphonic Dances (Op. 45), in an arrangement for two pianos nearly two months before the full orchestral version was published. By then, the habit must have become deeply ingrained.

Early in 1890 he wrote a two-movement string quartet, although chamber music never seems to have much interested him and the piece probably originated as an exercise for Arensky. It was performed the next year at a student concert, although arranged for string orchestra. Two songs are also dated from April and May of that year, although neither was published in his lifetime: ‘At the Gates of the Holy Abode’, to a poem by Lermontov, and ‘I shall tell you nothing’, to a poem by Fet whose many fashionable verses were set by other composers including Tchaikovsky. He also wrote an unaccompanied motet for mixed chorus in six parts, Deus meus, as a counterpoint set piece in two days under examination conditions. Years afterwards he dismissed it scornfully.2 It was with this piece that he would make his first appearance as a conductor on 24 February the following year.

At the end of May 1890 he journeyed some 450km south-west of Moscow to spend the summer at Ivanovka, the Satins’ estate. This was his first visit to what would become his Russian home, and he would return regularly until the Revolution, after which it was destroyed. Today the house has been restored and contains a Rachmaninoff museum. His four cousins included Natalia Satina, whom he later married, and Sophia Satina, six years his junior. Sophia outlived both of the Rachmaninoffs and their daughters and for more than thirty years after his death (she died in 1975) she remained an important source of biographical information.3 With its own farm, orchards, stable and studs and an English-style park cultivated by his aunt Varvara, it was a sizeable and well-organised estate where there were both family and guest houses. Like on so many Russian estates in those pre-revolutionary days, far from the then rapidly expanding urban world, the serfs who had lived there for centuries still felt bonded to the land. Situated far from the forest landscape that was familiar from his childhood, and the Crimea with its cliffs and beaches where he was taken by Zverev, it was not long before the landscape began to work a particular charm on him. ‘It had none of the beauties of nature usually thought of – no mountains, precipices or winding shore,’ he wrote years later. ‘The steppe was a seemingly infinite sea of fields of wheat, rye and oats stretching in every direction to the horizon, wavering and shimmering like water in the balmy summer haze.’4

That year there was a large house party which was attended by the Satins as well as the Silotis, their relatives, and the Skalons. General Skalon had three young daughters, Natalya, Ludmilla and Vera. The first piece of music Rachmaninoff would write at Ivanovka was a romance in F minor for cello and piano, for the youngest, Vera. The daughters were all fond of music-making and in the long summer days they delighted in Sergei, encouraging him to play the piano and accompany them in songs. Each girl was soon vying with the other to capture his attention. One unaccredited tale (presumably told by Sophia Satina) in Sergei Bertensson and Jay Leyda’s biography suggests that Vera’s mother was ‘horrified’ to hear that her fifteen-year-old daughter and seventeen-year-old Sergei were seen ‘sitting close together, and holding hands’. She soon put a stop to that.