13,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

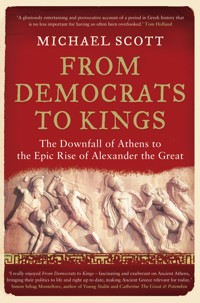

- Herausgeber: Elliott & Thompson

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

At all costs avoid blame. Such is the creed of dictators and politicians, tycoons and company chairmen, media celebrities and spin doctors the world over. But what about men at war, where the penalties for errors of judgement can be devastating? History is full of tales of those who have been wrongly castigated in the rush to find a culprit; only later, sometimes much later, when the real truth comes out, is the scapegoat exonerated. Exposed here are the real stories behind the myths that allow the reader to make a balanced judgment on history's fairness to the individual. From Admiral Byng, executed for 'failing to do his utmost' in 1757, to General Elazar, held responsible for Israel's lack of preparation at the start of the Yom Kippur War and General Dallaire, let down by the United Nations over the Rwanda massacres of 1994, these portraits of individuals unjustly accused span continents and centuries. The book begins with an introduction, defining the scapegoat and examining the conditions needed to qualify. This superbly researched book by a former professional soldier uncovers what might be termed the most disgraceful miscarriages of military justice.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 626

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Ähnliche

SCAPEGOATS

First published 2013 by Elliott and Thompson Limited 27 John Street, London WC1N 2BXwww.eandtbooks.com

ISBN: 978-1-908739-68-1

Text © Michael Scott 2013

The Author has asserted his right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as Author of this Work.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorized act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Printed and bound in the UK by T. J. International Ltd., Padstow

Typeset by Marie Doherty

‘And he shall take the two goats, and present them before the Lord at the door of the tabernacle of the congregation. And Aaron shall cast lots upon the two goats; one lot for the Lord, and the other lot for the scapegoat. And Aaron shall bring the goat on which the Lord’s lot fell, and offer him for a sin offering. But the goat, on which the lot fell to be the scapegoat, shall be presented alive before the Lord, to make atonement with him, and to let him go for a scapegoat into the wilderness.’

Leviticus 16:7–10

By the same author

(With David Rooney) In Love and War: The Lives of General Sir Harry and Lady Smith

CONTENTS

Foreword by Magnus Linklater

Acknowledgements

Introduction

1. Captain Jahleel Brenton CareyThe Killing of the Prince Imperial June 1879

2. Captain Charles McVayThe Sinking of the USS Indianapolis July 1945

3. Admiral John Byng‘Pour encourager les autres’ March 1757

4. Captain Alfred DreyfusJ’accuse October 1894

5. Lieutenant General James ‘Pete’ Longstreet 90The ‘Old War Horse’ of Gettysburg July 1863

6. Lance Corporal Robert Jesse ShortMutiny at Étaples October 1917

7. Major General Jackie Smyth VC MCDisaster of the Sittang Bridge February 1942

8. Lieutenant General Sir Charles Warren GCMG KCB‘Scapegoat-in-Chief of the Army in South Africa’ January 1900

9. Brigadier George Taylor DSO and BarThe Battle of Maryang San October 1951

10. Lieutenant Colonel Charles BevanScapegoat of the Peninsula July 1811

11. Marquis Joseph François DupleixNawab of the Carnatic August 1754

12. Lieutenant General David ‘Dado’ ElazarAtonement October 1973

13. Lieutenant General Roméo Dallaire OC CMM GOQ MSC CDMassacre in Rwanda April 1994

Plate Section

Epilogue

Sources

Picture Credits

Index

FOREWORD

by Magnus Linklater

General Mike Scott is well placed to write about military scapegoats – he might so easily have become one himself. As commanding officer of the 2nd Battalion Scots Guards in the Falklands War, he was in charge of the assault on the heights of Mount Tumbledown on the night of June 13/14, 1982. It was to be an attack conducted uphill in pitch dark and freezing weather, against experienced Argentine marines, dug into well-defended positions. As General Scott himself concedes in the course of this book, ‘There is an old military maxim that has stood the test of innumerable engagements: the odds favour the defender 3:1.’

He would have been well aware of that. He would also have known that, in the hours before the battle, he had twice questioned the orders he had been given, and twice succeeded in getting them changed. If, therefore, things had gone wrong, he would not only have borne the blame, his superiors could, legitimately, have pointed out that he was uniquely responsible for what had ensued. And Tumbledown was a close-run thing. Pinned down under sustained enemy bombardment, with dawn approaching, the battalion might well have had to withdraw, sustaining casualties as it pulled back. Instead it launched a bayonet attack, and, after fierce hand-to-hand fighting, took the last bastion that stood between British troops and the islands’ capital, Port Stanley.

General Scott’s absorbing account of military disasters, and those who were blamed for them, is full of knife-edge engagements like this – and the consequences that flowed from them. They are, in his hands, peculiarly fascinating, because he looks at them with a soldier’s eye. He points out how easily, in the ‘fog of war’, things might have gone another way, but he can also stand back to analyse why they went wrong, and then distil from them the evidence that points to those who were ultimately responsible.

Scapegoats are usually sought when reputations are at stake, and they tend to be found among the ranks of those who are closest to the action when disaster strikes. Not only are they the ones least capable of answering back, they are there, on the front line, smoking gun in hand, while everyone else runs for cover.

In almost every case that the author examines, however, he finds that the muddled orders, poor communications, failed intelligence, weak strategy or even cowardice of those in overall command were more often responsible for the outcome than those charged with carrying out the orders – though not always, of course, because General Scott is honest, too, about the failings of soldiers and the circumstances in which they operate. Grand strategy, he points out, may as easily be undermined by the actualities of war – tiredness, hunger, fear, lack of sleep, weather – as by poor decision-making or unclear objectives. The fatal blowing up of the bridge at Sittang in Burma in February 1942 might have been avoided if the officer who ordered it had not been suffering from painful sores in his backside. Would Gettysburg have been lost if General Lee, in command of the Confederate forces, had been a bit more outgoing and communicative, and his right-hand man General Longstreet less taciturn on the morning of the attack? The luckless Admiral Byng might not have faced a firing squad for failing to rescue a British stronghold in the Mediterranean if the wind had held up at the crucial moment.

The themes running through this book are as relevant in today’s theatres of war as they were in the campaigns and actions that General Scott describes. Time and again we find political or military leaders failing to connect with those whose responsibility it is to deliver the strategy. Chains of command are weak or non-existent; orders are imprecise or muddled; even experienced statesmen and generals, insulated from the realities of the front, can make catastrophic mistakes. And when the worst happens, their instinct is almost always to blame those further down the line.

General Scott is refreshingly brisk in his assessments of character. The governor of Gibraltar in Byng’s day is dismissed as ‘a useless soldier … obstructive, deceitful and pathetic’. General Sir Redvers Buller, commander-in-chief in the Second Boer War, is ‘a superb major, a mediocre colonel and an abysmally poor general’. General Wavell, responsible for the Burma campaign in the Second World War, was ‘not an easy man to understand and interpret, with his interminable silences’, while his ‘extraordinary out-of-touch demands and querulous telegrams’ contributed, in Scott’s view, to British setbacks against the Japanese.

He finds among this catalogue of disasters heroes, ill served by their superiors, who battle against great odds and then are blamed for what transpires: Brigadier George Taylor, ‘a straightforward, uncomplicated man with a love of soldiering and a deep respect for his men’, who was summarily dismissed in order to placate American allies after winning a stunning victory in Korea; Colonel Charles Bevan, a decent family man who killed himself after being made a scapegoat by Wellington for a setback in the Peninsula War; and Lieutenant General Roméo Dallaire, the hero of Rwanda, who attempted to avert a massacre and was abandoned by a supine United Nations which refused to give him the troops he needed.

Each inglorious episode is addressed by General Scott with the experience drawn from thirty-five years of soldiering. He weighs the circumstances, assesses the characters of those involved, then leaves the reader to form his or her opinion as to who should bear the final responsibility.

In the course of this unsparing account, we learn more about the military mind and the pity of war than we do in many a more conventional narrative. This is history from the inside – flawed, confused, frequently dysfunctional – which reminds us, nevertheless, that at the heart of great events are human beings whose fate is determined by forces over which they have little or no control.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The book covers a very wide spectrum of nationality, time, place and activity, so the help I had went much wider than, perhaps, I would have received for a single subject. Everyone has their pet scapegoat! A number of suggestions, therefore, would have happily qualified but I have tried to identify the most prominent, while spreading the time frame and country of origin.

I am indebted to Charles Messenger for his continual encouragement and suggestions. He suggested Dupleix, in particular, as a possible scapegoat although one, perhaps, more let down by his government, and cast adrift, rather than fitting the criteria. Philip Bambury redesigned the initial synopsis of the book to gather more succinctly the haywire of my thoughts. John Kiszely pointed me in the direction of Brigadier Taylor and David Elazar, and Randall Nicol, with his abiding interest in the First World War, was kind enough to scan the chapter on Corporal Short.

However, where I really started was with the descendants of Admiral Byng: the charming and ever-helpful Sarah Saunders-Davies and Thane Byng, introduced by Viscount Torrington, as direct a relative as can be in that convoluted family. I was privileged to be allowed into Wrotham Park by the Hon. Robert Byng where, with Felicity Wright’s help, I took photographs which I have their permission to print, together with the front of the park itself. Nigel Pascoe QC, one of my heroes from the Bar and author of the play To Encourage the Others: The Court Martial and Example of Admiral John Byng, supported me in my ‘third career’. I hope the chapter helps their drive to have the good admiral exonerated.

Viscount Slim sent me his copy of DEKHO! Journal of the Burma Star Association and introduced me to John Randle, one of the outstanding leaders during the Sittang Bridge disaster. The latter had little time for Jackie Smyth, a very understandable view from someone who saw his own troops decimated and stranded on the Japanese bank of the river. I hope, however, to have restored some balance to the story and was grateful for the views of Jackie’s grandson, Sir Tim Smyth, now a doctor in Australia, and for his permission to use the photograph. Didey Graham, secretary of the Victoria and George Cross Association, helped to add colour to Jackie’s later life.

I had lengthy and highly informative exchanges of emails with Julian Putkowski when writing the chapter on Corporal Short. Julian was one of the main drivers of the ‘Shot at Dawn’ movement, which resulted in the pardon for all those executed for alleged cowardice and desertion in the First World War. We did not always reach the same conclusions, but I was grateful for the time he took out of his very busy life.

Following a very interesting battlefield tour of the Peninsula Campaign run by Dick Tennant for the British Commission for Military History, I decided to include Charles Bevan who was the obvious scapegoat for the French escape from Almeida. Both Dick and Andy Grainger kindly carried out the ‘red ink corrections’ on my draft and gave me their approval. I was most grateful for Dick’s permission to use his photographs.

Of the chapters that rely on readers to reach their own decision, the one on Brigadier Taylor stands out. It was the most difficult one to see why he had been so treated. I am indebted to Beverly Hutchinson in Officers’ Records in Glasgow, who discovered the deliberations of the Army Council in the case, and to Leonie Seely, George Taylor’s daughter, for allowing me access to the documents and to use his photograph. Hew Pike’s father’s papers, sadly, failed to reveal anything, but I was grateful for Hew’s interest. Tony Cran, the Intelligence Officer of 1 KOSB at the time, was as helpful as he could be, but admitted that, from his level, the machinations of those higher up were beyond his pay scale! Robin Davies, in Australia, was very interested as he is writing the story of the Battle of Maryang San, but neither of us could throw any more light on the situation than I have done.

My old friend from Sandhurst days (The Sovereign’s Company 1959), Joe West, helpfully commented on the Longstreet chapter. Coming from someone who gained the highest points ever recorded in the specialised subject on Mastermind (American Civil War), this was value indeed. Ed Coss, Associate Professor of Military History US Army Command and General Staff College, introduced me to Josh Howard, one of America’s experts on the Civil War, who was kind enough to read the final draft and gave me invaluable advice and encouragement. I was also in correspondence with Susan Rosenvold of the Longstreet Society in America, which tries to reduce the damage done to the ‘Old Warhorse’.

I owe a huge debt to Hanoch Bartov, a close friend of David Elazar’s. We had a number of email and telephone exchanges and he honoured me with an inscribed copy of his book, Dado, 48 Years and 20 Days. I return the compliment with a copy of this one in the hope that I have done his old friend the justification he deserves. Yair, David Elazar’s son, was also enormously helpful and allowed me to publish the letter from his father to Golda Meir on his resignation. It was elegantly translated by Ildi in Tel Aviv.

My one living scapegoat is, of course, Senator Roméo Dallaire. He is not actually a scapegoat, although he would have been if the United Nations could have engineered it. A victim of the perfidy and apathy of the Security Council, he is a hero to many, including me, and it was very valuable therefore to have his approval and comments on Chapter 13.

I am most grateful to Barbara Taylor for the elegance of the maps from my often spidery drafts and a variety of sources. An enormous thanks must go to my publishers Lorne Forsyth, Olivia Bays and Jennie Condell who put in a great deal of hard work and gave me endless ideas, help and encouragement. They are an outstanding team.

Finally, Magnus Linklater wrote a typically thoughtful and penetrating foreword, which was a great honour.

INTRODUCTION

At all costs avoid blame. Such is the creed of dictators and politicians, tycoons and company chairmen, media celebrities and spin doctors the world over. Identify a suitable scapegoat and make them take the blame. The idea that ‘it must be someone else’s fault’ is a sad principle of a modern world. Today we see this in Cabinet leaks, kiss-and-tell tabloid exposures, Tweeting, super-injunctions and Wikileaks, but the tactics used to deflect the finger of blame or, better still, bury the knife in someone else’s back, have never changed. To hold someone else accountable allows people to move on and avoid responsibility for the immediate past. Finding a scapegoat provides a relief and release for everyone except the victim. The urgency to do this is often out of step with the proper speed of justice. History crawls with the tales of those who have been wrongly castigated by people in a rush to find a culprit, any culprit, as soon as possible. Only later, sometimes much later, when the real truth comes out, is the scapegoat exonerated. For others, the mud sticks forever.

But what about men at war? Often those with the most to lose are the military scapegoats. The penalties for errors of judgement, the responsibility for avoidable casualties or the blame for the loss of national prestige can be devastating. This book is about them.

Exposed here are the real stories that allow the reader to make a balanced judgement on history’s fairness to the individual. Military scapegoats can be found across the ranks and throughout the world and, although the officers, as commanders, bear responsibility for much of what went on, this has been no bar to those lower down being blamed. This book covers ranks from general to lance corporal, a US Navy captain and a civilian marquis; about half are British and the remainder American, French, Israeli and Canadian. It is arguable that they were all scapegoats, and they have been chosen to reflect that, regardless of nationality or status. Each chapter stands on its own; they are presented not chronologically, but in an order that will contrast the differences between the individuals and their stories.

In military history, the man himself is so often more interesting than the military industrial base, equipment, balance of forces, obstacles, firepower and the like. This is not to say that the latter were not vital to the outcome of any major campaign; of course, they were. However, the fascination is not only the interaction between commanders at all levels and the troops under their command, but also their own qualities in times, invariably, of extreme stress. What were the effects of illness, tiredness and exhaustion, fear and anxiety? Field Marshal Earl Wavell wrote to Sir Basil Liddell Hart: ‘If I had time and anything like your ability to study war, I think I should concentrate almost entirely on the “actualities” of war – the effects of tiredness, hunger, fear, lack of sleep, weather. … The principles of strategy and tactics and the logistics of war are really absurdly simple: it is the actualities that make war so complicated and so difficult.’ For the men under them, George MacDonald Fraser put it so aptly in his superb Quartered Safe Out Here, ‘With all military histories, it is necessary to remember that war is not a matter of maps with red and blue arrows and oblongs, but of weary, thirsty men with sore feet and aching shoulders wondering where they are.’ This is to say nothing of elements well beyond individual control. Were these the demons that tipped the scales into an irrecoverable situation where the man carried all the weight, became the scapegoat and took all the blame?

‘Scapegoat’ in the old biblical sense one might think highly convenient: load all one’s sins onto someone else, expel him into the desert and start with a clean slate. Fine, unless the scapegoat returns, having survived the desert, and poses some uncomfortable questions or, by his very presence, constitutes a threat. Brigadier Jackie Smyth, who was blamed for the Sittang Bridge disaster of 1942, and was highly critical of the official historian’s subsequent coverage of the operation, is a prime example. The best scapegoat was, clearly, a dead one. Admiral Byng, executed on the quarterdeck of the Monarch in 1757 for failing to engage the enemy, and Lance Corporal Short, for inciting mutiny in Étaples in 1917, happily for their detractors, fitted the bill.

To most, a scapegoat is someone who has been unfairly accused or has taken the blame for something that has gone wrong. However, it is not always as simple as that. People have been blamed or vilified not necessarily in order to cover up someone else’s ineptitude but, often, through pure envy and jealousy.

Professor Norman Dixon, in On the Psychology of Military Incompetence, elaborates on the process:

This process [the discovery of scapegoats], to be efficient, must whitewash the true culprits (and their friends) while effectively muzzling those who might be in a position to question this action. This muzzling is a subtle process, the main inducement to silence being the unspoken threat that any attempt to undo the ‘scapegoating’ might put the undoers in jeopardy. Secondly, it must ‘discover’ scapegoats who are not only plausible ‘causes’ but also unable to answer back. Thirdly, it must impute to the scapegoats undesirable behaviour different from that which actually brought about the necessity of finding a scapegoat. By so doing it distracts attention from the real reason for the disaster and therefore from the real culprits.

So, even more complicated. One might call this person the ‘non-scapegoat’; in other words, the individual who is allowed to go unpunished because to do so would expose others. Was General Sir Redvers Buller in 1900 such? Or was he quite justifiably to blame for Spion Kop and the weak message to the besieged in Ladysmith? Lieutenant General Sir Charles Warren was certainly partly responsible and Buller ensured he was made the scapegoat. Astonishingly, nothing happens to Buller until considerably later when he is ‘compelled’ to resign over a speech he made.

An unpleasant aspect of scapegoating is the undue haste in which the action is taken – the ‘quick fix’ – and how very indicative this is of the vulnerability the accusers must feel. The luckless Captain Carey, ostensibly in charge of the patrol on which the French Prince Imperial was killed by the Zulus in 1879, was court-martialled and cashiered within ten days of the event. Lord Chelmsford, the commander-in-chief, had just suffered humiliating defeat at Isandlwana and, having had his reputation saved by courageous soldiers at Rorke’s Drift, clearly did not want any blame attached to him for the Prince’s death.

The French marquis, Dupleix, Clive’s opposite number in India in 1754, may be a name vaguely known but, since he was virtually cast out by his own country and died in penury and obscurity, it is unlikely. Few will know of Charles Bevan, a battalion commander in the Peninsula War. He so enraged Wellington after the French escaped from Almeida in 1811 that Bevan ultimately took his own life, preferring not to live with the disgrace.

David Elazar, the real hero of the Yom Kippur War in 1973, was forced to resign in the wake of the Agranat Commission. Later, the Israeli people would not tolerate it, and Golda Meir, who should have supported him, and her government, including Moshe Dayan, were removed from office. Elazar died, a broken man, aged 50.

Substantial rivers have always been military obstacles, even with today’s sophisticated crossing equipment. An opposed river crossing almost beats breaching a minefield for one of the least attractive operations in the soldier’s book. So capturing a bridge intact is a jewel worth every effort. Likewise, successfully defending it is as valuable. The opportunities for blame to be levelled when things go very publicly wrong are legion. The Sittang Bridge in Burma in 1942 was blown when much of the 17th Indian Division was left on the eastern, Japanese side of the river. Brigadier Jackie Smyth was unjustly accused of ‘losing Burma’ by this action. However, like many events in these stories, it was not quite as simple as that.

On 29 July 1945, the USS Indianapolis, under command of Captain Charles McVay, was torpedoed by a Japanese submarine in the Pacific. The ship sank with the loss of more than 800 crew. McVay was court-martialled and convicted of hazarding his ship. Yet why was he in waters known still to contain enemy submarines without being warned? What had happened to the intelligence assessments? Who knew of the dangers but allowed the ship to sail, unprotected? How convenient to let the unfortunate captain shoulder the blame.

A sacrifice to the gods of appeasement produces the occasional scapegoat. To preserve the cooperation of allies or the integrity of a formation, it becomes necessary to single out an individual to blame for a disaster. In Korea in 1951, the newly formed 28th British Commonwealth Brigade went into action. A very experienced Second World War battalion commander with two DSOs, Brigadier George Taylor, commanded it. Operation Commando was a success albeit after a very difficult protracted battle involving British, Australian and New Zealand troops. For many, the large, jocular Taylor was a popular leader, particularly among the Australians. However, stirrings among some of his British commanding officers and fairly open hostility from the New Zealanders led to his being peremptorily replaced. The cohesion of the international formation could not be risked.

The battle of Gettysburg was the most significant defeat for the Confederates in the American Civil War. Although it was not the final engagement, it marked the beginning of the end. For the South, their hero, General Robert E. Lee, had failed. How could this happen? There must be a reason for it. It was impossible, in Confederate eyes, for this man to have been outmanoeuvred and out-fought by General Meade. He must have been let down. How and by whom? The finger of disappointed ex-Confederates, promoters of the ‘Lost Cause’, pointed at Longstreet, one of Lee’s corps commanders – the man who had argued with his leader, was allegedly late on the second day and then responsible for not supporting Pickett’s breakthrough – surely, a cast-iron scapegoat.

Captain Alfred Dreyfus was a Jew. Convicted of high treason in 1894, he was sent to Devil’s Island and not exonerated until 1906. The case was a complete fabrication, motivated by military paranoia, political opportunism and personal greed. Contrary to popular misconception, the French military hierarchy was not racially institutionalised, although, reflecting the standards of the day, it had its fair share of those who took no trouble to conceal their dislike of Jews. Nevertheless, it was highly convenient to blame a Jew and the newspapers were quick to whip the public up into a frenzy of anti-Semitic hysteria, making him the scapegoat and letting him carry all the blame for whatever ills Jews were seen to be causing the country.

The final chapter is about General Roméo Dallaire and his mission for the United Nations in Rwanda during the massacres of 1994. A man of outstanding moral and physical courage, who faced unbelievable carnage on an hourly basis, he never gave up trying to persuade the UN where their responsibilities lay and would never desert ‘his’ Rwandans. The Belgians, and no doubt others, would have made him a scapegoat for their own utter inadequacies, but could not do so. He certainly felt as such in the aftermath when they court-martialled one of his best officers. He is included, therefore, not as a scapegoat who fits the criteria, but as an example of what happens to a man when he is deserted, in effect, by the international consortium and abandoned to fight his own battles on their behalf.

The stories in this book are of people, many of whom, on the whole, faced appallingly difficult, life-threatening decisions that affected themselves, their men and their responsibilities. A few do not come out of it very well; some unfairly took the blame; others accepted what happened to them with varying degrees of grace. The judgement of whether they were really scapegoats or deserved their fate, ultimately, must rest with the reader. Before being too critical, armchair warriors should recall what Joseph Conrad wrote in An Outcast of the Islands: ‘It is only those who do nothing that make no mistakes.’ He was not entirely right; of course, mistakes are often made by people prevaricating or failing to grip a situation. Earlier, Marshal Turenne had put it better, saying, ‘Show me a general who has made no mistakes and you speak of a general who has seldom waged war.’ Finally, before weighing in with the benefit of hindsight, we should note what Professor Sir Herbert Butterfield wrote in George III, Lord North and the People 1779–80: ‘One of the perpetual optical illusions of historical study is the impression that all would be well if men had only done “the other thing”.’ Quite.

ONE

Captain Jahleel Brenton Carey

The Killing of the Prince Imperial

June 1879

As scapegoats go, Captain Carey’s story is arguably the prime example of how blame can be pushed down from above onto one who did not deserve it.

If Shakespeare had been alive in 1879, he would surely have written The Tragedy of the Prince Imperial. The tale had all the components he loved so much: high-born players, passion, battle, courage, death, failure and cover-up. He would not have had to invent anything, although he might have written the ending in brighter colours.

Eighty years later, officer cadets in the Sovereign’s Company at the Royal Military Academy, Sandhurst, looking out of the window could see a statue of the Prince Imperial (see plate III) gazing out over the playing fields and lake. With the indolence and arrogance of youth, they paid it little attention except on high days and holidays when the statue was adorned with inappropriate articles or daubed with paint. They knew little of the Prince and cared even less. A study of the Anglo-Zulu War was usually confined to Stanley Baker’s and Michael Caine’s parts as Chard and Bromhead winning VCs at Rorke’s Drift in the film Zulu.

So why the statue of this Frenchman? What was he doing in the British Army not that long after the French, the old enemy, had been so soundly beaten in 1815 and, more recently, by the Prussians? How and why had he met his end in a relatively unknown war a long way from home? What military incompetence and social unease had led to his death – and where had the blame been subsequently spread to absolve those responsible?

The origins of the Anglo-Zulu War, like many other wars, were simple, but the fighting – bloody, difficult and lasting much longer than anticipated – and the conclusion and extraction were much more complicated than planned. Disraeli’s government had reluctantly supported the war, without expressly authorising it. As ever, there was increasing exasperation with escalating costs and the length of the campaign.

Europe’s seafaring nations had a strong interest in the Cape as it provided the ideal base for ships sailing between the Atlantic and Indian Oceans. South Africa was a convenient and benign staging post for ships rounding the Cape. The Dutch were the first settlers but, in the seventeenth century, had made little effort to colonise further inland and were content merely to grow enough crops and manage water systems to provide for the various fleets. Amid the turmoil of the Napoleonic Wars, the British, nervous of French expansion and influence, seized the Cape by force. By the early 1800s, the Dutch settlers, augmented by other refugees such as the Huguenots and unprepared to accept the shackles of British administration, pushed inland to set up their own largely farming communities. In the 1830s, the Great Trek, as it became known, was relatively haphazard and raised tensions and animosity with the local tribes through whose territory it crossed and on which the Boers settled. British authority was left, effectively, on the coast in an uneasy relationship with the settlers. From 1820 onwards, the British had encouraged large numbers of people to settle in the Eastern Cape and this increased demand for expansion into what many thought, incorrectly, were the empty lands of the Veldt. In Natal, north and east of the Cape, the legendary Zulu chief, Shaka, established a powerful warlike tribe which, inevitably, came into conflict with the Boers. The British formally colonised Natal in 1843, pushing the settlers even further inland. Uneasy local treaties were formed with the Zulus and other tribes. The latter sometimes took the opportunity to break from the Zulu yoke and side with the British. In essence, the British kept a presence in South Africa because of the sea route. There was very little wealth to be extracted from the colony and the government in Whitehall merely desired a quiet and uncomplicated life with South Africa.

This changed dramatically in 1867 with the discovery of diamonds at Kimberley. At once, British eyes opened to visions of unbelievable wealth and profit. A loose confederation of the various states, such as the Transvaal and Orange Free State, under British rule suddenly became attractive and, in 1877, this was declared in Pretoria, to the disgust and confusion of the Boers. It was not difficult to see that, in addition to alienating the Dutch, the British were going to go head to head with the Zulus in their northern Natal kingdoms. A confrontation with the new king, Cetshwayo, was inevitable. The British administration in South Africa anticipated a quick success with a modern army against spear-carrying savages, followed by a leisurely peace in which to sort out the difficulties. As history has so often demonstrated, it does not always work like that. After the British issued a deliberately unacceptable ultimatum to the Zulus in December 1878, the Anglo-Zulu War began in January 1879.

The British commander for this swift action was Lieutenant General Lord Chelmsford. He was a professional soldier with experience in the Crimea, the Indian Mutiny and Abyssinia in 1868. Despite that, he was not an innovative military thinker and, as generals are sometimes criticised for doing, he tended to fight today’s battles with the last war’s tactics. Having overcome the weak Xhosa tribes relatively easily, he was overconfident when dealing with the Zulus. Chelmsford failed to gather sufficient intelligence on the Zulus’ modus operandi, their strengths or whereabouts. He had to rely on an inadequate, and indifferently trained, force of a mixture of British soldiers, volunteer horsemen and locally raised native militia. Coupling these defects with a severe misjudgement of his own and a superbly and courageously orchestrated Zulu attack, the result was the disaster at Isandlwana where 1,300 of Chelmsford’s men were killed, a third of his effective force. The outstanding defence of Rorke’s Drift immediately following this defeat was probably the only thing that saved Chelmsford from dismissal. The effect at home was devastating and Chelmsford was frantically reinforced with virtually all that he asked for. Among these reinforcements appeared Louis Napoléon Bonaparte and Lieutenant Jahleel Brenton Carey of the 98th Regiment of Foot.

Napoléon Eugène Louis Jean Joseph, the Prince Imperial of France, was born in Paris on 16 March 1856. He was the son of Napoleon III, emperor of France, the third son of Louis Bonaparte, king of Holland in the time of his brother, the great emperor Napoleon Bonaparte. The prince’s mother was Eugénie Marie de Guzman, younger daughter of the Spanish Count de Montijo and his Scottish wife, Donna Maria Kirkpatrick. As both his parents spoke English well and his nurse was English, it was not difficult for him to acquire the language fluently. When he was 14, the Franco-Prussian War broke out and, on 19 July 1870, dressed in the uniform of a sous-lieutenant, he rode out with his father, who was to take personal command of the French forces. On 2 August, he had his first experience of battle at the skirmish of Saarbrücken. The war, however, was short-lived and Napoleon III surrendered to the Prussians on 2 September. The emperor was taken prisoner of war and Eugénie and Louis sought sanctuary in England. Napoleon was soon released by the Prussians and joined his wife and son at Chislehurst in Kent where they were befriended by Queen Victoria. Given Prince Albert’s natural antipathy to the Bonapartes (he was a Coburg) and British Francophobia, this was difficult to understand, particularly as Victoria still firmly endorsed the views of her husband, although he had been dead for eighteen years. One can only put it down to Victoria’s very firm views on the sanctity of the European monarchies, whose crowned, or nearly crowned, heads were, in many cases, her relations. Many people regarded Napoleon III at best as a lightweight fop, and at worst, an inadequate upstart, but, nevertheless, there were those who had some sympathy for his predicament.

In 1872, to his great delight, Louis became an officer cadet at the Royal Military Academy, Woolwich. Woolwich then trained officers for the Royal Artillery and Royal Engineers, while Sandhurst trained the cavalry and infantry. Napoleon Bonaparte himself had started life in the artillery, so what could be more appropriate for his great-nephew? Louis was extrovert and energetic and engaged in outlandish bouts of skylarking and showing off. Was this to compensate for his rackety upbringing and very uncertain and ambiguous future? With no actual commission in the British Army, despite his education at Woolwich, he could not command troops nor fill a post on the staff. What was he to do? The Establishment had made a serious problem for itself. He must have carried considerable psychological baggage. Dr Adrian Greaves, the historian and consultant clinical psychologist, clearly explains:

I believe Louis was destined from birth to become a neurotic extrovert. At first sight, this might indicate him to be a gregarious, flamboyant risk-taker keen to impress. He may well have appeared to everyone as such but in psychological terms, he had serious and destructive psychological problems…An extrovert is one who ‘shows out’ behaviour in order to make up for under-arousal, usually as a child. Children who are controlled or repressed, frequently because they have suffered the controlling influence of the parental ‘learning curve’ need, in teens and onwards, to express themselves to make up this deficiency. It is common for adventurers and ‘high flyers’ to come from strict families and many are the first born; subsequent siblings are more relaxed as their parents settle into parenthood.

The Prince Imperial certainly fits the criteria for classification as both a neurotic and an extrovert. His parents reared and educated him with one role in mind, to become the future Emperor of France. Sadly for Louis, exile to England severely curtailed this process leaving him a victim and with every need to re-prove himself. It is no wonder that he employed his inner childhood tactics of showing off to gain credibility.

Was this the reality behind his application to the commander-in-chief, the Duke of Cambridge, to serve in South Africa? It cannot have been through any ‘political’ thoughts of his own, which, if anywhere, would have directed him towards his own country’s interests in Austria and the Balkans. No, it was clearly a desire to prove himself, coupled with his romantic nature and sense of destiny. He needed to taste his own ‘whiff of grapeshot’. The Anglo-Zulu War contained the required spice of danger with, for him, no international complications. But for the Commander-in-Chief, what was the Prince Imperial actually going to do? Perhaps some nice little sinecure could be arranged, tucked away in Chelmsford’s headquarters, well out of harm’s way? With the tacit approval of Queen Victoria, the Duke overcame Disraeli’s refusal to allow the Prince to go with the understanding that the boy was to be there in a private capacity with no official standing. Disraeli was apoplectic but Cambridge had slipped it past the Queen and rid himself of a minor, but potentially major, irritation. The Duke wrote to Sir Bartle Frere, the high commissioner in South Africa:

I am anxious to make you acquainted with the Prince Imperial, who is about to proceed to Natal by tomorrow’s packet to see as much as he can of the coming campaign in Zululand in the capacity of a spectator. He was anxious to serve in our army having been a cadet at Woolwich, but the government did not think that this could be sanctioned; but no objection is made to his going out on his own account, and I am permitted to introduce him to you and to Lord Chelmsford in the hope, and with my personal request, that you will give him every help in your power to enable him to see what he can. I have written to Chelmsford in the same effect. He is a charming young man, full of spirit and energy, speaking English admirably, and the more you see of him, the more you will like him. He has many young friends in the artillery, and so I doubt not, with your and Chelmsford’s kind assistance, will get through well enough.

This was the first of the buck-passing exercises, which were going to be so useful later.

The Prince reached Durban on 31 March 1879 and, accompanying Lord Chelmsford, moved with the headquarters to Pietermaritzburg. On 8 May, Chelmsford reached Utrecht and the Prince was placed under Colonel Harrison, the assistant quartermaster general (AQMG) who was responsible for the administration of the command. Far from being tucked away as the Duke of Cambridge wished, however, Louis was allowed out on patrol.

We must now turn to the other main player in the drama, Lieutenant Jahleel Brenton Carey. He was born in Leicestershire on 18 July 1847, the son of a parson. Interestingly, he was educated for much of his early life in France. He could, of course, speak fluent French and had adopted many French mannerisms and perceptions, which was subsequently to his advantage in his relationship with the Prince Imperial. On graduation from Sandhurst, he was commissioned into the West India Regiment, at the time serving in Sierra Leone. ‘Colonial’ regiments such as these were unpopular in military circles and lacked cachet and sophistication. However, officers could live on their pay while others in ‘smarter’ regiments, based at home, required a private income. Foreign service, such as with Carey’s regiment and those regiments of the Indian Army, also provided a good quality of life and the opportunity for advancement through distinguished service in ‘small wars’.

Such a small war occurred in 1867 in Honduras, to which Carey’s battalion had been sent to deal with friction between the settlers engaged in logging and the local population. In one action, a British patrol under Major Mackay was badly ambushed, which resulted in a rout for the security forces. Major Mackay was duly censured but Carey, who had been instrumental in covering the withdrawal of the unlucky force, emerged with a good deal of credit. There appeared to be no doubt as to his personal courage. Carey had clearly adopted a professional approach to his career which, in some circles, was disdained by those who thought they could succeed by mere amateurism.

Carey returned to England in 1870 suffering from the debilitating effects of service in the fever-ridden swamps of Central America, married and settled down to a solid career. Particularly devastating for him, though, was when he was placed on ‘half-pay’. This was a sort of semi-redundancy whereby the government could reduce the officer corps but maintain a hold over them for future expansion if needed. To someone of Carey’s financial means and newly married this was a real blow. However, with the onset of the Franco-Prussian War, he volunteered for service with the English Ambulance. Speaking French, he emerged with a decoration for ‘his conduct in the relief of French wounded’. With this behind him he was able to obtain a commission in the 81st Regiment of Foot, with a subsequent transfer into the 98th, then stationed in the West Indies, his familiar haunt.

In 1878, he passed the Staff College course well and quickly volunteered for service in South Africa. He travelled out with a draft of reinforcements on the SS Clyde. As bad luck would have it, the Clyde was holed on a sandbar 3 miles offshore, unpleasantly close to where the SS Birkenhead had famously gone down in February 1852. Carey, together with the other officers, organised the disembarkment from the sinking ship and set up camp ashore. Not one man was lost and after their speedy rescue by HMS Tamar, the officer in command, Colonel Davies, formally mentioned Carey in dispatches for his outstanding conduct. This did nothing but good for his self-confidence.

What sort of man was he? His courage was proven, his ambition properly in evidence and his professionalism well developed. He was tactically experienced and battle inoculated in Honduras and the Franco-Prussian War. With a steady family background and an unusual education in France, he was clearly an asset in anyone’s unit or headquarters. He was conscientious, hard-working and probably rather dull for the more extrovert younger officers. Working in a headquarters, at whatever level, is not much fun for an officer who prefers to soldier with his men, and for both Carey, with his front-line experience, and Louis, a young man thirsting after adventure and the opportunity to prove himself, Chelmsford’s camp must have seemed boring and restrictive.

It is also important to realise how the two would have related to one another. Carey, with his French upbringing would have, naturally, been an attraction for the Prince, and his combat experience a subject of admiration. For Carey, the Prince represented a completely different world and, in those Victorian times when social divisions, even within classes, were strictly maintained, Louis might have come from another planet. Although, of course, the Prince was not a commissioned officer, Carey would have been very careful not to give him strict or peremptory orders. To a certain extent they would have been thrown together in the headquarters, with Carey being Colonel Harrison’s number two as deputy assistant quartermaster general (DAQMG), and Louis a sort of extra aide-de-camp (ADC) for whom there could be no proper job.

Part of Carey’s responsibility was to carry out reconnaissance for future campsites and, in the absence of reliable maps, find safe routes capable of taking the ox-drawn wagons. This work involved making sketches and hand-drawn mapping, which both he and the Prince were relatively good at. With varying degrees of success, Louis was allowed to accompany some of these patrols.

Louis, however, was rash and impetuous and there were a number of instances when he rushed off on a reckless frolic of his own, to the annoyance of the patrol commanders and not least danger to himself. People like Captain Bettington, an experienced commander of irregular Natal Horse, whose men – scruffy and ill-disciplined compared to conventional British cavalry, but, nevertheless, highly versed in soldiering in the Veldt – had little time for him and regarded him as a dangerous nuisance. Soldiers, on the whole, like their young officers to show a certain amount of ‘form’, but not to the extent that it leads them into danger or they have to go and pull them out of trouble. Ian Knight in his masterly With His Face to the Foe quotes Colonel Buller voicing concerns about the Prince to Lord Chelmsford, who ordered Harrison to ensure the Prince did not leave camp without a proper escort. This he put in writing. (Harrison’s Recollections of a Life in the British Army was not published until 1908, by which time, presumably, memories had faded and the temptation to put a gloss on the more difficult occurrences of June 1879 must have been irresistible.)

By 30 May 1879, Chelmsford was ready to push forward; routes had been recced, cavalry protective screen deployed and the first night’s campsite had been selected. Intelligence, such as it was, suggested that the Zulus would not oppose the advance until well after the second night’s bivouac. So, when Louis badgered Harrison to be allowed to leave camp and take out a patrol, the latter anticipated little danger and, as Carey agreed to accompany the patrol to verify some of his earlier sketches, Harrison was reassured that the Prince would be safe under his supervision. Clearly, there was no real need for this additional patrol, and whether Harrison merely wanted to be temporarily rid of the tiresome Prince when he had much work to do, or whether he just wanted to be pleasant to the young man, can only be guessed. He therefore agreed and, allegedly, put in writing orders (which were never found) containing the proviso that the patrol was to be protected by a suitable escort. It was unclear who was actually in command of the patrol: Louis could not be, as he held no rank, and Carey was merely ‘accompanying’ the patrol to verify his previous sketches, so perhaps it was thought the escort commander, possibly Captain Bettington, would be in command?

Accordingly, Carey approached the brigade major of the Cavalry Brigade to order an escort from Bettington’s Horse and the Natal Native Horse. Six men were detailed from Bettington’s troop and Carey was told to put in an order for the rest of the escort (the Basuto auxiliary element) to their commander, Captain Shepstone. There was then a muddle. Carey merely left the order with Shepstone for the Basutos and hurried on. By the time the Basutos had fallen in, Carey and the rest of the patrol, including a friendly Zulu guide, had left. Carey sent a message to Captain Shepstone to have his men meet them at a forward rendezvous and left with the impatient Prince. Whether there was an inference that Captain Shepstone would accompany his Basutos, and therefore possibly command the patrol, can only be conjecture. Bettington’s men were experienced soldiers and included a sergeant and a corporal. Carey, no doubt, had full confidence in them and happily expected to be joined shortly by the rest of the escort.

The rendezvous for the Basutos coincided with the position for the division’s first night’s camp. While Carey and Louis were waiting there, Colonel Harrison and Captain Grenfell appeared, in order to mark out the areas for the various components of the division. Harrison reinforced his instructions to Carey and the Prince that they were not to proceed without the Basuto escort, then left. Grenfell, having completed his tasks, agreed to accompany Carey and Louis for part of the way. Maybe this, and the Prince’s increasing dominance of the patrol, persuaded Carey to allow the small force to push on without waiting for the Basutos. It is not difficult to see the self-confident and impatient Louis asserting himself with Carey and the soldiers. He had been used, all his life, to deference, even from senior army officers, and Carey would have been highly conscious of this. Additionally, right or wrong, Carey did not see himself as the commander of the patrol. That is not what he volunteered for. He was, in his own eyes, merely there to amend his sketches. With hindsight, one might wonder how he could have possibly thought this, knowing full well the Prince had no rank and could not possibly be put in command. Had Colonel Harrison’s orders been properly given out, which they may have been, the ‘command’ paragraph would have been mandatory and abundantly clear. It is difficult to imagine that there was any option other than Carey commanding the patrol in the absence of any other officer. But in the turmoil before the patrol left, did Harrison actually issue the order?

Grenfell accompanied the patrol for about 7 or 8 miles and then left to return to the main camp, saying cheerfully, ‘Take care of yourself, Prince, and don’t get shot.’ Louis responded, pointing to Carey, ‘Oh no! He will take very good care that nothing happens to me.’

A while later, they came upon an unoccupied small collection of about eight or ten huts (kraal) and various cattle pens and decided to take a break, unsaddle the horses and let them have a roll and graze on some of the nearby mealies (maize). While it was quickly apparent that there were no Zulus occupying the kraal, there was thick grass growing up to 5 or 6 feet high and a dried-up water course, a donga, providing a very obvious concealed approach towards the kraal. Despite Carey’s experience, and that of the Bettington’s Horse NCOs, none of this was ‘cleared’ by even the most cursory close-in patrol around the area. No sentries were posted – not even a single lookout – and no order was given to load weapons (apparently the latter were carried unloaded when men were mounted). One wonders what the sergeant thought he was doing? His job, when the officer is busying himself with map reading, planning or putting his orders together, is to bustle about dealing with standard basic procedures: posting sentries, producing a roster, designating alarm positions, loading weapons with safety catches applied and pointing out the emergency rendezvous. Only then can a brew-up take place. This is not making a judgement by today’s standards; these procedures were firmly in place in those days and had been for many years before.

The Prince and Carey sat around chatting in the hot sun. At about half past three, Carey suggested saddling up and moving on. After a brief delay, with reluctance the Prince agreed and the patrol started to round up the hobbled horses. As they were doing so, their native guide reported seeing a Zulu down by the main river. This does not appear, though, to have caused particular alarm; he could merely have been a local herdsman. Saddling up proceeded, and by about four o’clock the Prince (note, not Carey) gave the order to mount.

At that moment they were attacked by a force of about forty to fifty Zulus who had crept up unobserved through the long grass and the dead ground of the donga. They appeared about 20 yards away before opening fire. These Zulus were a harassing group of enemy whose job it was to act separately from the main body and pick off small parties of British when the opportunity arose. Fit young men, they would have relished their independent and special role. There was a volley of shots from the Zulus which, while not very accurate, came as such a profound shock to the members of the patrol that immediate panic set in. Carey was already in the saddle and others had varying success in mounting as the terrified horses bolted. The Prince was in severe trouble. He had not been able to mount his horse but was running alongside, grasping a stirrup leather or part of the saddle. At some point, his grip broke. The last anyone saw of him, he was running along the donga closely pursued by about a dozen Zulus. Carey and Troopers Cochrane and Le Tocq scrambled their horses over the donga and were joined by Corporal Grubb and Sergeant Willis. Trooper Abel had been brought down with a shot and there was no sign of Trooper Rogers or the native guide.

Carey had completely lost any control if, indeed, he had any in the first place. He paused to look round at the pursuing Zulus and realised the Prince had not made it. The patrol was too spread out and beyond effective voice range to rally even if, by doing so, they could have resisted the attackers. What weapons they had left with them were unloaded in any case. There was, at that point, no question of being able to save those who had not made their escape. Had they tried to do so, there is no doubt that they would all have been killed. Eventually, they managed to regroup and the pursuers gave up the chase. The full realisation of the appalling tragedy started to become apparent. There was only one option: to return to the main camp and bear the consequences.

As the news of the Prince’s death spread, a shock wave was felt throughout the army and, subsequently, at home. On 9 June, Chelmsford sent an immediate telegram to the Secretary of State for War in England:

Prince Imperial under orders of AQMG recced on 1 June road to camping ground of 2 June accompanied by Lt Carey DAQMG and 6 white men and ‘friendly Zulus’. Halted and off-saddled about 10 miles from this camp. As the Prince gave the order to mount a volley was fired from the long grass around the Kraals. Prince Imperial and 2 troopers reported missing. Lt Carey escaped and reached this camp after dark. I myself not aware that Prince had been detailed for this duty.

One can already sense the speedy raising of an umbrella in the last sentence.

With the loss of Isandlwana, a defeat from which he never properly recovered, and now this, Chelmsford sank into deep despair. Colonel Harrison could also feel a cold chill running up his spine. The Prince was his responsibility. He had it in writing from the General. How was this going to be handled without them both going down?

While there were those who were quick, and justifiably so, to criticise Carey, there were also those who, perhaps considering the situation a little more deeply, thought, ‘What would I have done in similar circumstances?’ Certainly, among the survivors of Isandlwana, there would have been a number who might not have considered themselves to have been entirely covered with glory. There was an uncomfortable feeling that Carey was being lined up as a scapegoat. An immediate Court of Inquiry was held and the prima facie evidence was wholly damning against Carey: he could say little to justify the fact that the patrol had bolted; the troopers with him were quick to say Carey was first to run; there was no attempt to hoist up onto the survivors’ horses those who failed to mount; and Carey was unable to absolve himself from responsibility for commanding the patrol. The court had no alternative but to recommend Carey be tried by General Court Martial on a charge of ‘misbehaviour before the enemy’. He was promptly removed from his appointment as DAQMG on Harrison’s staff. There were those who might have considered this to be punishment enough and, possibly, under normal circumstances this would have been a distinct possibility; ambushes happened and there were casualties and not everyone behaved exactly as others thought they should, but they were not court-martialled. But these were not ordinary circumstances; the heir to the French Empire had been killed. What would have happened if Prince Harry had been on a reconnaissance with the Americans in Afghanistan, ambushed by the Taleban, killed and deserted by members of the patrol?

Carey’s court martial began on 12 June, eleven days after the Prince’s death. In the midst of serious campaigning, it is difficult to understand how proper arrangements could be made and a court of experienced officers assembled, let alone the prosecution and defence be given enough time to prepare their cases. The speed with which this happened raises the inevitable suspicion that there was an anxiety to have Carey firmly nailed before anyone else could be held to blame. It is not surprising, therefore, that the proceedings would end in embarrassment and come to haunt the hierarchy to such an extent that the record would be barred from the public in the National Archives at Kew, not for a standard thirty years, as normal for secret and sensitive documents, but for a hundred years. Not until 1979 were people allowed access; by then everyone involved was safely dead.

The court opened with a colonel as president and four other officers. In attendance was a major as officiating judge advocate. Names were read out but there is no record of the members being sworn. Carey was charged that: ‘He having misbehaved before the enemy on the 1st June 1879 when in command of an escort in attendance on His Imperial Highness Prince Napoleon, who was making a reconnaissance in Zululand, having when the said Prince and escort were attacked by the enemy galloped away, not having attempted to rally the said escort, or otherwise defend the said Prince.’ Carey pleaded not guilty and the prosecutor, Captain Brander, then outlined the case for the prosecution – he would call witnesses to show a map of the action and where the bodies were found, and the survivors to cover precautions taken and the subsequent behaviour of the prisoner. He would also call the AQMG, Colonel Harrison, to prove Lieutenant Carey was in command of the whole party. Finally, he would call evidence to show the cause of death.

Carey decided to defend himself. Nowadays this would be considered unwise but he may have felt sufficiently self-confident to answer the charges or, in the time available, been unable to identify someone to defend him. Long before the days of the Army Legal Service, it might have been difficult to find someone of the calibre required or even someone with sufficient sympathy for Carey that he would be prepared to risk others’ opprobrium in allying himself with such an obvious loser.

The map markings were shown, and agreed. Then Captain Molyneux, an ADC to General Chelmsford who was on the expedition to recover the Prince’s body, was asked what position the Prince held on the General’s staff. Molyneux proved vague, as well he might. The fact was that the