7,19 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Fitzcarraldo Editions

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

'After many years I had excised myself from the life I had led in town, just as one might cut a figure out of a landscape or group photo. Abashed by the harm I had wreaked on the picture left behind, and unsure where the cut-out might end up next, I lived a provisional existence. I did so in a place where I knew none of my neighbours, where the street names, views, smells and faces were all unfamiliar to me, in a cheaply appointed flat where I would be able to lay my life aside for a while.' In River, a woman moves to a London suburb for reasons that are unclear. She takes long, solitary walks by the River Lea, observing and describing her surroundings and the unusual characters she encounters. Over the course of these wanderings she amasses a collection of found objects and photographs and is drawn into reminiscences of the different rivers which haunted the various stages of her life, from the Rhine, where she grew up, to the Saint Lawrence, the Hooghly, and the banks of the Oder. Written in language that is as precise as it is limpid, River is a remarkable novel, full of poignant images and poetic observations, an ode to nature, edgelands, and the transience of all things human.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Ähnliche

‘River is an unusual and stealthy sort of book in that it’s the opposite of what it appears to be – which is a rather apt dissimulation, as it turns out. Yes, it rifles through both the rich and rank materials of the world, turning over its trinkets and its tat, in a manner that is initially quite familiar – however, this curious inventory demonstrates an eye for the grotesque and does not hold the world aloft, or in place. Here, details blur boundaries rather than reaffirming them, positing a worldview that is haunted and uncanny. Shifting through unremarkable terrain we encounter the departed, the exiled, the underneath, the other side. We are on firm ground, always; yet whether that ground is here or there, now or then, is, increasingly, a distinction that is difficult and perhaps irrelevant to make. Sea or sky, boy or girl, east or west, king or vagrant, silt or gold; by turns grubby, theatrical, and exquisite, we are closer to the realm of Bakhtin’s carnival than we are to the well-trod paths of psychogeography. Kinsky’s River does indeed force us to stop in our tracks and take in the opposite side.’ — Claire-Louise Bennett, author of Pond

‘Esther Kinsky’s novel outlasts everything that has recently been published in the German language with patient stamina. It is full of culture without being erudite, and full of knowledge without being smart-alecky. River is a democratic book, witty, wise and touchingly beautiful.’ — Katharina Teutsch, Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung

‘Written in a style that is both precise and dream-like, River is a great book about the obliteration of landscape.’ — Christine Lecerf, Le Monde

‘An extraordinary book and a major writer.’ — Nelly Kapriélan, Les Inrockuptibles

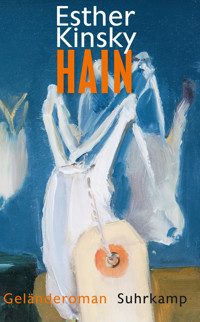

RIVER

ESTHER KINSKY

Translated by

IAIN GALBRAITH

For the blind child

Contents

‘Your eye, the wanderer, sees more.’

— Charles Olson, ‘A Discrete Gloss’

I. KING

Some time before I left London I happened upon the King. I saw him in the evening, in the turquoise twilight. He was standing at the park entrance gazing east, where a deep, blue haze was already ascending, while behind him the sky was still aglow. Moving out of the shadow of the bushes by the gate he took a series of short soft-footed steps to the edge of the green, above which, at this time of the day, the many ravens of the park flew in restless circles.

The King stretched out his hands and the ravens gathered around him. Several settled on his arms, shoulders and hands, briefly flapping their wings, lifting again and flying a short distance, then returning. Perhaps each bird wanted to touch him at least once, or perhaps they had no choice. Thus encircled by birds, he began to make gentle swinging and circling movements with his arms, as if they were haunted by a memory of wings.

The King wore a magnificent headdress of stiff, brocaded cloths, held together by a clasp adorned with feathers. The gold thread of the brocade and the clasp itself still gleamed in the declining light. He was attired in a short robe, with gold-embroidered edgings shimmering around his neck and wrists. The robe, which hung to his thighs, was bluey-green and fashioned from a taut, heavy fabric with a woven feather pattern. His long black legs protruded beneath the cloth. They were naked, and on his bare, wizened-looking feet, whose wrinkles contrasted oddly with his youthfully slim and sinewy knees and calves, he wore wedge-heeled sandals. The King was very tall and stood upright among these birds, and as he let his arms circle and swing his neck remained straight and steady, as if he kept a whole world in his headdress. His profile stood out against the western sky, and all I can say about it is that it was regal, conversant with grandeur, but also used to desolation. He was a king turned melancholy in his majesty, far from his country, where his subjects probably thought of him as missing or deposed. Nothing about his figure was connected to the surrounding landscape: to the towering age-old trees, the late roses of a mild winter, the surprising emptiness of the marshland opening up beyond the steep downward slope at the edge of the park, as if this was where the town abruptly ended. In his stark solitude he had emerged as a king at the edge of a park that the great city had more or less forgotten, and these birds with their sooty flutter and fading croaks were his sole allies.

The park was empty at this hour. The observant Jewish women and children who walked here during the afternoon had long since gone home, as had the Hasidic boys, whom I sometimes espied at lunchtime nervously giggling and smoking behind the bushes. Their side-locks trembled when they were cold, and, as I saw from the length of the red glow that briefly appeared in front of each mouth in turn, they drew far too hurriedly on the cigarette they were passing round, while a hubbub of voices and children’s singing carried in waves from the windows of their school beyond the park hedge, rising and falling in the wind. The rose trees, with the exception of those still sporting yellowish-pink blossoms in this frostless, misty-white winter, carried dark red rose hips. By the time of day when the King put in his appearance, the rose hips hung drably in the dusk.

At the foot of the slope, behind the trees, flowed the river Lea. In wintertime its water glittered between the bare branches. Behind it stretched the marshland and meadows, which, as evening fell, resembled the enormous palm of a hand full of ever thickening twilight, across which the occasional brightly lit train snaked on its north-easterly journey along the raised embankment.

It was quite still in the early evening when I walked back through the streets from the park to my flat. Now and again an observant Jew would come hurrying by, giving me a wide berth as he passed; more rarely still I would see children; they were always rushing along to prayers, a meeting, a meal, or some other duty. They often had rustling plastic bags of shopping dangling from their hands, especially loaves, which stood out visibly through the thin polythene. On Saturdays and holidays, when windows were open in warmer weather, the sing-song of blessings could be heard on the street. There was the clatter of china, children’s voices, small groups of the pious passing to and fro between temple and home. In the evenings the men stood in the glow of the street lamps laughing, their faces relaxed, the feast behind them.

Back in my flat I stood at the bay window in the front room and watched the day turning to night. The shops on the other side of the street were brightly lit. Greengrocer Katz packed delivery boxes until late in the evening, orders for prudent housewives and their families: grapes, bananas, biscuits, soft drinks in various colours. Once a week, in the morning, Greengrocer Katz took delivery of these soft drinks. The orange, pink and yellow plastic bottles were manhandled out of a lorry on pallets and shouldered by assistants to be carried to a storeroom at the back of the shop.

Next door to Greengrocer Katz was a pool club, which stayed open until the early hours. Men, always black, could be discerned in the dim, smoke-filled interior, often pacing with a thoughtful stoop around the pool tables, or leaning over them, intently focussed. Big cars halted in front of the café; men came and went, often accompanied by beautiful, strikingly-dressed women. There were fights. Once there was a gunshot; the police appeared, followed by an ambulance, and the flickering blue of its light filled my room.

After many years I had excised myself from the life I had led in town, just as one might cut a figure out of a landscape or group photo. Abashed by the harm I had wreaked on the picture left behind, and unsure where the cut-out might end up next, I lived a provisional existence. I did so in a place where I knew none of my neighbours, where the street names, views, smells and faces were all unfamiliar to me, in a cheaply appointed flat where, for a while, I would be able to lay my life aside. My furniture and packing cases stood about in the cold rooms in a random jumble, apparently committed to oblivion, just as undecided as I was, and uncertain whether a serviceable domestic order of any kind could ever be re-established. We, the objects and I, had left our old house one blue and early morning with the August moon still visible against the bright haze of a late summer’s sky, and we were now loafing about in East London, all our prospects wintery. Tirelessly, we played out the farewell scenes we hadn’t had. With a slowness that seemed like eternity, imaginary cheeks and hands brushed, teardrops welled in the corners of eyes, interminable trembling of every book’s, picture’s or piece of furniture’s lower lip, throats choking on speech at every turn; a slow-motion valediction, turning to a scar before the ending had even come, every second of it as long as a day, and all movement heavy going, an unspeakable crunching as through frozen snow.

When I slept I dreamed of the dead: my father, my grandparents, people I had known. In a small room accessed by several steps from the main flat, and just long enough for me to stretch out and sleep on the floor when I felt like it, I spent hours trying to memorise every detail I saw in the yard, the garden, and the section of the street that was visible between two houses. I got to know the light too. From April until August I read what the big sycamore wrote on the one-windowed brick wall of a neighbouring house at the bottom of the garden. It was late summer, it was autumn, then it was winter. Spring came, a west wind, shadows of leaves scribbling notes to the station, where a few metres beyond the garden on the tracks below a train came to a halt every quarter-hour. Or, more seldom, a north wind, with the last leaves flickering unquietly across the whole wall in the sharp light; by midday the shadow of the treetop was as clearly defined on the wall as the map of some unknown town. Winter, after a stormy autumn, was unusually windless, and the bare tree appeared on the wall as a barely perceptible shadow in the uniformly milky light; it wrote messages that were hard to decipher, as if sent from far away, but which, because of the peaceful justice shown by this light towards all things that lacked shadows, were not sad.

I lay awake at night, listening to the new noises around me. The trains beyond the garden stopped with a long-grinding groan and a sigh. In time, I learned that the groaning sounds came from the trains on their way from the city centre, which, shooting out of a tunnel just before the station, seemed taken aback by the proximity of the platform and ground to a halt, whereas the commuter trains bound for the centre sighed and softly squeaked. Somebody on crutches that creaked like old bedsprings hobbled about on the narrow path between the garden and the railway embankment, which fell away to the platforms and tracks. The man on crutches sometimes sang, a sound that was quiet and dark; the contours of his head could be made out in the lamplight, looming above the fence. He was doing business, and his customers came and went, the wind bringing scraps of their conversation. Sometimes he was forced to make a run for it, and the metallic wheezing of his spring-borne crutches would recede amid the flurry of thumping feet of those who had taken flight with him.

Foxes were mating on the flat gravel-strewn roof of an annexe. They let out yearning barks and cries, and the chippings scattered in all directions under their darting, scrabbling paws, some flying against the window of my room. Once I went to the window to look. Motionless in the lamplight, the foxes stared right at me. From that moment onwards I thought of the man on crutches as fox-like.

I spent my days walking in the area, enjoying the sight of the pale Hasidic children in their islands of sheltered piety, on their way to school, or running messages to the shops, and remembered the little girl in West End Lane whom I had often encountered on afternoons years before, with her calf-length, dark-blue skirt usually askew, her thick glasses and fine hair. She was always alone, pushing her small but forceful determination in front of her fearful, short-sighted eyes like a wedge before which the pedestrians approaching on the pavement would part to let her pass. Here, the children went in groups, white-skinned and fearful of strangers, keenly devoted to their own world; maybe this was a good life, secluded from the things that were going on outside their streets. Shortly after arriving in the area I happened upon Springfield Park. It was a cloudy day, and not many people were about. A group of gaily dressed African women were toing and froing between the viewing-bench niches along the cropped hedge, apparently looking for something. They called aloud to one another, glancing here and there, staring down at the ground as if attempting to rediscover a track they had followed into the park and subsequently lost. A flock of crows rose into the air, their beating wings creating a commotion; after a semi-circle over the grass, they settled again on the other side of the lawn, watchful of the rose bushes, the African women, me.

There were also houses in the distance across the marshes, but it was as if they belonged to a different country. The rose beds, the rare exotic trees, the extensive glazing of the sleepy café, the trimmed hedges around the benches, all of these signified a town, contrasting with the land that stretched out at the foot of the slope: flatlands on thin ground over water, already a part of the Thames Estuary area.

The river Lea, here dividing the town from open terrain, does not have a long journey. Rising among the low hills to the northwest of London, it flows through smiling countryside before reaching the frayed urban edgelands and snaking through endless suburbs. It then casts an arm around the old, untameably streetwise, commercial centre of London, and finally, eight miles southeast of Springfield Park, and as one of several solicitous tributaries from the north and west that deposit their sand and gravel at the city’s feet, flows into a Thames that is already bound for the sea. On its way, constantly brushing with the city and with the tales told along its banks, the Lea branches, forms new little arms that reach into the meadowland and boggy thickets, hides for a couple of miles at a time behind different names, but after squirming in indecision and unravelling into its muddy delta, it has no choice but to flow between the factories and expressways of Leamouth into the Thames, which it reaches just upstream of the sea-monster-like gates of the flood barrier and the large sugar factory, which, for riverboats, marks the mouth of the city.

The Lea is a small river, populated by swans. White, still and aloof, almost imperceptibly hostile to spectators, they sail through the dwindling light. That autumn, however, I noticed how many of them were intent on becoming wild. They chased each other across the water, flying a couple of metres above the surface, uttering helpless, sullen cries, their underwing plumage dirty and ruffled, their stretched out necks and focussed heads fiercely thirsting for adventure. A few moments later they would be floating along on the surface again, each and every one of them Crown property, sometimes coveted by migrant Gypsies, who, so people said, loved them for their gamey, somewhat bitter flavour.

Now that I had discovered the park and the marshes, the paths I followed led me there almost every day. I generally walked downstream, a little bit further each time, sticking to the river as if clutching a rope while balancing on a narrow footbridge. On its back the river carried the sky, the trees along its banks, the withered cob-like blooms of water plants, black squiggles of birds against the clouds. Between the empty lands to the east of the river and the estates and factories along the other bank, I rediscovered bits and pieces of my childhood, found snippets cut from other landscapes and group photographs, unexpectedly come here to roost. I stumbled on them between willows under a tall sky, in reflections of impoverished housing estates on the town side of the river, amongst a scatter of cows on a meadow, in the contours of old brick buildings – factories, offices, former warehouses – against an exceptionally red-orange sunset, along the raised railway embankment where forlorn-looking, quaintly clattering trains receded into the distance, or when watching roaming gangs of children lighting fires and burning odds and ends, fighting each other close to the flames, and unresponsive when a mother, standing between lines of flapping washing, held one hand up to shelter her eyes as she called them in.

I saw the King when I returned from my walks. Leaving the river behind me, I would climb the slope and there he would be at the top, on the grass plateau, or still on his way from the shadows by the entrance, like a sentinel. Without wanting or knowing it and certainly without noticing me returning from the river, he marked for me the moment of transition between a landscape abandoned to all kinds of wildness, and the city.

I did not come across the King in any other place, and had trouble imagining him in a flat in the dark red-brick building opposite the park entrance, or in one of the newer, rough-and-ready terraces along my short walk from the park to the loud main road I had to cross. I felt relieved never to have seen him emerging from one of the dark alleyways between the old blocks of flats, or returning to the pale cone of lamplight in the doorway of one of the box-like houses.

II. HORSE SHOE POINT

At the foot of Springfield Park was a small village of houseboats on the river Lea. Surrounded by swans, the boats had presumably long since become one with the mud and rushes, their taste for cruising the river lost in days gone by, their anchors inextricably snarled in the roots of the bushes along the bank. As long as it was not too cold in the evenings the inhabitants sat on deck, clattering with plates and cutlery, while cats arched their backs between pots of geraniums. With all pretence to mobility forfeit, this theatre of sedentariness was, for the time being, the city’s parting word. On the other side of the river was an alder carr, a semi-wild place where mist would gather on colder days. This whole grove could have become the Erl-King’s enchanted realm had not park employees, unschooled in wildness, tried their hand at deforestation. They had wanted to get the better of this place between marsh and alder grove: they had tried to turn it into a picnic spot, but had evidently reconsidered. Table and bench stood athwart wild growth on a levelled triangle of grass, hemmed in by mounds of earth that were now overgrown with weeds. The felled trees in the alder carr lay where they had fallen. The glade was a product of senseless decimation, and was already thick with saplings. Despite the celandine and wild green of the anemones and violets surrounding the abandoned tree trunks and orphaned stumps, it remained a scene of devastation, for a moment awakening a similar unease in me to that aroused by the little aisles cut through the woods of my childhood, where the raw stumps of felled trees jutting out of the low undergrowth, those cleanly sawn seats, spelled only the absence of any gathering, and my grandfather, in his tone of voice reserved for warnings, would say: Hush now – for these are the seats of the Invisible!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!