Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Crown House Publishing

- Kategorie: Bildung

- Sprache: Englisch

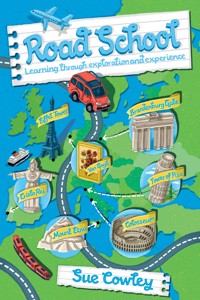

Frustrated by a regime of statutory testing, and keen for a midlife adventure, Sue Cowley and her partner decided to step out of the system, and set off on the educational adventure of a lifetime with their children. Road School is the story of their family's adventures around Europe and across China, and what they learned along the way. Part comedy travelogue, part parenting guide, part educational philosophy, Road School asks you to consider what 'an education' really means and offers tips for anyone planning their own learning adventure. As a parent in the UK, you must make sure that your child has a full time education, once they are of compulsory school age. However, this education does not have to take place in a school. A growing number of parents are finding that home educating, or 'unschooling', either permanently or on a short term basis, is a viable and attractive option. The national curriculum, benchmark tests and exams serve to reinforce the idea that there is a specific set of knowledge which equates to 'an education'. However, when you are home educating, it is entirely up to you what and how you wish to teach your children. Or, rather, what and how you wish your children to learn. You might choose to include part or everything that is in the national curriculum, or you might not. Sue's family found that one of the best things about Road School was the freedom to follow their interests. Sue offers plenty of advice based on the lessons her family learned on their Road School adventure, such as: take into account how learning can happen simply by visiting a place and exploring it. Don't feel that you always have to formalise your visit by turning it into a 'lesson'. The experience of going somewhere can be memorable and educational in its own right. Much of what your children will learn on the road is social and emotional rather than intellectual. They learn how to cope, how to adapt, how to be resilient and how to be brave. The challenges and difficulties that you face on the road will teach them all these things without any direct 'teaching' needed at all. Involve your children in making decisions about the content of their curriculum, particularly when it comes to choosing topics or themes. What would they most like to study during your learning journey together? You can teach subjects such as English or history through cross-curricular 'themes' rather than as discrete lessons. Ask your children to decide which topics interest them the most and capitalise on those. One of the great things about educating your child yourself is that you get to learn alongside them. Not only do you provide a model of lifelong learning, but it's also very liberating to learn new things as an adult. Remember that teaching is not the same thing as learning. You don't have to teach your children directly for a set number of hours each day in order to educate them. Learning can take place all the time, and anywhere, rather than just during 'school' hours. It doesn't matter what time of the day or day of the week it is - if there is learning happening, then your child is being educated. Contents include: England, English Lessons, Stepping Out of the System, The Netherlands, Dutch Lessons, The Practicalities, Germany, German Lessons, Cultural Literacy, Italy, Italian Lessons, An Education, Portugal, Portuguese Lessons, Travelling with Children, France, French Lessons, Pussycat Parenting, China, Chinese Lessons, A Road School Curriculum.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 353

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Praise for Road School

The sense of wonder and adventure in Sue Cowley’s engaging account is palpable. Travel is one of the great educators and there is no more exciting and effective way of learning than through experience. At a time when ministers would have our children do little more than sit in a classroom, Road School suggests an alternative which is every bit as valid and powerful as conventional learning.

Dorothy Lepkowska-Hudson, freelance journalist and writer

Cowley’s Road School is an entertaining, accessible and practical guide to home education on the road.

Fiona Nicholson, home education consultant

Road School is a rip-roaring romp through Europe and China. It is not only the story of a family, which kept me chuckling out loud, but also a reflection on both parenting and education and politics today.

Anyone who teaches, and anyone who has a family of their own, will enjoy this book – not just for the entertainment value, but also for Sue’s insights into what is really important when you work, and live, with children.

This book is an inspiration. I might not be off for six months, but I am certainly eyeing my suitcases with a glint in my eye and a bit more bravery.

Nancy Gedge, consultant teacher

Road School is an inspirational and lyrical journey, offering the reader a unique approach to home schooling on the road. Crossing continents with her partner and children, Sue describes how it is possible to offer an exciting and enriching curriculum, which eclipses conventional schooling by travelling and exploring the world. Any parent or teacher who reads this book will find themselves imagining life on the road with their children and many will adopt this approach. It is a magnificent book, which will start an educational revolution, mirroring Sue’s awe-inspiring angle on education.

Mike Fairclough, Head Teacher, West Rise Junior School and author

For the real life ‘Frank’, ‘Alfie’ and ‘Edith’.

The world is a book, and those who do not travel read only one page.

Anon

Contents

England

Ready to Go

‘I want to go travelling,’ I said, sliding a copy of The Rough Guide to Europe across the dining room table to where my partner Frank was sitting. Frank caught the book and looked up from his laptop. He had a spreadsheet open and he was tapping numbers into it. The spreadsheet had the title: ‘Household Expenses’. Radio 5 Live was playing in the background.

‘Huh?’ Frank said, shaking his head. ‘Like a holiday, d’you mean?’

‘No, not a holiday,’ I said. ‘Proper travelling. Where you leave home and you don’t come back for months on end. That kind of travelling.’

‘And how would we pay for this?’ Frank entered some more numbers into his spreadsheet. Frank’s an accountant. He likes to know how much everything will cost. (It’s a good thing somebody in our family does.)

‘It’s the ideal time to do it,’ I said, leaning over to turn down the volume on the radio. I wanted to explain my reasoning as fast as possible. If QPR scored a goal in the match I was dead in the water. I had my speech all prepared.

‘The kids are at the perfect age,’ I said. (Our son Alfie had just turned 11; our daughter Edith was 8.) ‘Alfie gets to avoid the whole Year 6 “endless months of preparing for SATs” thing. And Edith is a bright spark – she’ll love the adventure. Plus, once they start secondary school we’ll be stuck in England for the next eight years at least. And, as an added bonus, we get to spend lots of time with our children.’

‘I don’t want to spend lots of time with my children,’ Frank said.

When I was a child my parents had a VW camper van, and one summer we went on tour in it. Thinking back, this happened shortly before they got divorced, so maybe there was a correlation between the two events. On our trip we toured around France, Switzerland and Italy. Quite how my parents managed to do this without the Internet, the euro, TripAdvisor or the EU, I have no idea, but my memories from that holiday are still vivid, forty years later. This was the kind of adventure I wanted to recreate for our kids: strange new places, dusty tracks, exotic smells, the magic of exploration and the open road.

Frank typed a few more numbers into his spreadsheet, sighed deeply, then looked up and finally met my eyes.

‘Is this even legal? Aren’t they meant to be in school all the time or we get put in jail?’

‘Home schooling isn’t illegal, Frank. Not yet, anyway. We can teach them on the road,’ I said. ‘Or, rather, the road can teach them.’

‘You mean you can teach them.’ Frank scratched his goatee. ‘You didn’t answer my question about who pays for it. Travelling costs money. We can’t work if we’re travelling.’

‘It wouldn’t have to be expensive,’ I shuffled in a bit closer to him and draped my arm across his back. ‘We could both take a bit of time out. I was thinking we could hire a camper van. It would be romantic. And I could write a book about it. That way it would be tax deductible.’ (Frank finds it very seductive when I talk about things being tax deductible.)

‘I’m six foot five,’ Frank said. ‘I don’t do camper vans. Can you imagine trying to drive a motor home into the centre of Rome?’ He paused for a moment. ‘No camper vans. And I want to fit in a visit to China. I’ve always fancied going to China.’

‘Is that a yes?’ I could hardly believe it.

Frank sighed again. It was the deep, long, heavy sound he makes when he is resigning himself to one of my crazy ideas.

‘It’s a yes,’ he said, turning up the radio again to show that we were done. ‘I guess that us going travelling is better than you having an affair, buying a fast car or learning to ride a motorbike. I think I’d better start a new spreadsheet. I’ll call it “Midlife Crisis”.’

Everybody Wants to Rule the World

‘If we’re going to do this, I want to go to India, China and Japan,’ Frank said. ‘Oh, and South America.’

‘You’re ambitious.’ We were arguing about the route for about the millionth time. ‘I was thinking more a road trip around Europe, finishing up in Paris. Then maybe a week in South America.’

‘I’m definitely not going to Paris,’ Frank shook his head as though he had a bug in his ear. ‘I’ve been there too many times already. Don’t you remember when we were in our twenties and Tom lived there? We used to visit him all the time.’

‘My main memory of those days is of getting drunk and staying up until dawn, Frank,’ I sipped my tea. ‘That wasn’t exactly the kind of visit to Paris I had in mind.’

Frank made a harrumph sound. ‘I did the Interrail thing around Europe when I was a teenager. I’ve got some great stories about that. Mind you, it’s probably best if you don’t put those in your book. I’d like to go back to Germany, though. See the places where I spent time as a child.’

‘Well, if we’re going to India, China, Japan and South America, I’d really like to go to Malaysia or Indonesia,’ I said.

‘Japan sounds good. How about Brazil?’

‘Yes, North America too. And Hawaii. I’ve always wanted to visit Hawaii.’

A week later we had argued about the route another million times. I had communed with Google and I had the ammunition I needed. ‘Okay,’ I said to Frank. ‘I’ve got some figures for round-the-world flights taking in Malaysia, China, Japan, Hawaii and Brazil.’

‘And?’

‘And it comes to £3,832.27.’

Frank smiled. ‘That sounds doable.’ He began to tap some numbers into a spreadsheet.

‘Each.’

‘Ah.’ His fingers stopped tapping. ‘A road trip around Europe it is, then.’

‘We should do one other destination. We’ve already been to India, Hawaii is too far and too expensive, and South America is full of poisonous bugs.’

‘Like I said before, I’ve always fancied going to China.’

And that was that. Finally. Decision made. Destinations chosen. Now all we had to do was make it happen.

Bright Side of the Road

The kids were in the living room, collapsed on the sofa, watching TV after a long day at school. They were trying to munch their way through a packet of chocolate chip cookies before we noticed. We were pretending not to notice the disappearing chocolate chip cookie trick, because we had something much more important to talk about. I cleared my throat and made the announcement.

‘We’re taking you out of school.’

‘Yay, cool,’ Edith glanced up at me for a moment and then returned her gaze to the TV.

Frank came to stand beside me in a show of fatherly solidarity. ‘We’re going to go travelling around Europe, and then after that we’ll fly to China. We’ll be on the road for six months. Isn’t that exciting?’ he said.

‘Yeah, great,’ Alfie said. His eyes were still on the TV.

‘We’re going to learn through exploration and experience,’ I said. ‘No timetable. No SATs. No uniform. No teachers. No limits. We’re going to educate you … on the road.’ I’ll admit that my voice broke with emotion a bit at that point. I thought I was doing a good job of selling the dream.

‘Sure, whatever,’ Alfie said. He shrugged.

‘You’re a teacher, mummy, so there will be teachers,’ Edith pointed out.

‘She doesn’t count,’ Alfie said.

‘Yes she does.’

‘No she doesn’t.’

‘Yes she does.’

‘No she doesn’t.’

‘Thanks kids.’ Their level of enthusiasm wasn’t exactly inspiring.

‘Aren’t you excited?’ Frank wanted to know.

‘Yes! We’re really excited!’ the kids shouted.

‘Now can you be quiet?’ Alfie said, exasperation in his voice. ‘We’re trying to watch South Park.’

Breaking the Law

The pages of my little black Road School notebook were filling up fast with lists of places to visit, museums and art galleries to see, hotels to book, things to pack. And rules. There had to be rules. You can take the teacher out of the classroom, but you can’t take the classroom out of the teacher.

‘We’re going to need some rules for Road School,’ I said as I scribbled another note in my notebook.

‘What is it with teachers and rules?’ Frank was typing some numbers into yet another spreadsheet. I looked over his shoulder. The title of the spreadsheet was ‘Petrol Prices: Europe’.

‘What is it with accountants and spreadsheets?’ I stuck my tongue out at him.

‘Why do we need rules? We’re not exactly the rules oriented kind of people.’

‘Rules are important. Rules help to create the right environment for learning. It’s not just a free-for-all. These kids are going to need rules.’

‘If you want rules, you go ahead and make some up,’ Frank said. ‘Just don’t expect me to follow them.’

‘Or us,’ the kids piped up from the sofa.

‘How about if I make up some rules that we will all like?’

‘Doesn’t that kind of defeat the object?’ Frank asked.

‘No one likes rules, mum,’ Alfie said. ‘That’s why schools have them.’

‘I think you’ll like these rules,’ I said. ‘Why don’t you just listen and see what you think? Turn off the TV for a minute.’ I grabbed the remote and paused South Park. ‘You really shouldn’t watch this stuff anyway.’

‘Aww mum!’ Alfie said.

‘That’s our favourite episode of South Park,’ said his little sister. ‘It’s the one where they go to an aqua park and end up swimming through a tsunami of urine.’

‘Just give me five minutes.’ I held up my notebook and tried to read my scrawled handwriting. ‘Here you go. The First Rule of Road School is that we are on the move – the only constant is change.’

‘Very poetic,’ Frank said. ‘What does it even mean?’

‘That’s not really a rule, mum,’ Alfie said. ‘It’s more a statement of fact. Obviously we’re going to be on the move, because otherwise it wouldn’t be called Road School. It’d be called Staying At Home School.’

‘I like the first rule, mummy,’ Edith said, smiling at me. ‘Especially the changing constantly bit. That’s great.’ I think she was just trying to make me feel better.

‘Can I continue?’ I said. They all nodded and Frank made a ‘get on with it’ signal with his hand. ‘The Second Rule of Road School is that we hunt for interesting things – we are looking for learning.’

‘I’m interested in learning about guns and volcanoes,’ Alfie said.

‘I’m interested in learning about Leonardo da Vinci,’ Edith said.

‘I’m interested in lunch,’ Frank said.

‘Noted. Can I continue?’ I’m not going to lie and tell you they looked particularly enthusiastic about my rules, but I was on a roll now and I was damn well going to get through them.

‘The Third Rule of Road School is that you have to write a page in your diary every day. I got you these,’ I said, holding up two hard-back A4 lined books.

‘I don’t like rule number three,’ Edith said.

‘Me neither,’ Alfie agreed.

‘Tough,’ I said.

‘Why do you have to ruin our trip with writing?’ the kids whined.

‘Because it’ll keep the authorities off my back,’ I said, ‘Plus you’ll thank me when you’re older and you have it as a memento. You can stick tickets, maps, postcards and all sorts of things in your diaries as well. It’ll be a brilliant record of what we did.’

‘I don’t have to keep a diary, do I?’ Frank said.

‘No you don’t, Frank, because you’re old already.’

Frank gave me a look. ‘So are you,’ he said. Then he muttered something under his breath that sounded suspiciously like ‘bloody midlife crisis’.

‘Is that the last of the rules, mum?’ Edith said, stifling a yawn and looking longingly towards the TV, where Kyle was paused in mid-stroke as he swam through a giant pool of pee to hit the emergency release valve.

‘Last one,’ I said. ‘The Fourth Rule of Road School is that some rules were made to be kept, but some rules were made to be broken. We just need to figure out which rules to follow and which ones to break.’ I was pleased with this rule. Road School meant no uniform, no timetable, no government tests, no detentions, no homework. We were breaking the rules, right, left and centre.

‘Now this rule I like,’ Frank said. ‘This is a rule I can live with.’ Frank likes to think of himself as a bit of a rebel, although I’m not convinced that a desire for rebellion and a love of spreadsheets are natural partners.

‘Hey, dad!’ Alfie said. ‘I’ve got a great idea!’

‘What’s that?’

‘I’m going to apply rule number four to rule number three. That way I don’t have to do any writing.’

‘Great plan,’ Frank said.

‘Good idea, Alfie! I’m going to do that too,’ his sister joined in.

‘Well, that’s just perfect,’ I said. I tore the page of rules out of my notebook, screwed it up into a ball and threw it in the bin. ‘You have to write in the diaries. That rule is not up for negotiation.’

‘Dictator,’ Frank said.

‘Tyrant,’ Alfie said.

‘Meanie,’ Edith said.

‘Thanks for the compliments.’ I snapped my little black notebook shut and handed the remote control back to the kids. ‘But you can just call me mum.’

Heroes

The moment she learned that we were going to be travelling around Europe, Edith became obsessed with Leonardo da Vinci. She was interested in him before she found out about our trip. She had a library book from school about Leonardo that she read over and over again. Now she wanted to read every book ever written about him, visit everywhere he ever lived and see every painting, sculpture and model he ever made. It was pure, unadulterated childlike curiosity, fired up by an interest in something. Why does the education system stop us sustaining this feeling in kids? I was hoping that our road trip would help me to figure this out.

‘Leonardo was born in Vinci,’ Edith said. ‘So obviously we have to visit Vinci.’

‘I’ll put it on the list,’ I said, scribbling in my notebook.

‘We have to see the Mona Lisa,’ she added. ‘That goes without saying.’

‘I’ve already told your mum – I’m not bloody going to Paris,’ Frank said, looking up from his spreadsheet. ‘I’ve been there a million times already.’

‘We’ve got to take them to Paris, Frank,’ I said. ‘You can go for a long lunch while we go up the Eiffel Tower and visit the Louvre.’ Frank made a sound that was somewhere between a snort and a huff. I made another note in my notebook.

‘Anywhere else, Edith?’ I should really have kept my mouth shut at that point.

‘The Last Supper,’ Edith announced. ‘We definitely must see The Last Supper. It’s Leonardo’s greatest masterpiece, alongside the Mona Lisa. Where’s that one?’

‘I think it’s in Milan. I’ll check now.’ I opened my laptop and fired up Google.

Unless you’ve ever tried to visit The Last Supper, you’ll have no idea how difficult it is to visit The Last Supper. You might imagine that you could just roll up in Milan, pay your entrance fee and go in to see it. But you’d be wrong. Instead, you have to book a slot for your visit by calling a phone number in Italy. When you call the phone number in Italy it is permanently engaged. When you eventually get through and talk to the woman in the ticket office, you have to nominate a specific day and time to visit. But you can’t choose just any day or time. You must nominate one of only a few fifteen minute slots that are available, several months in the future.

During her reading, Edith was particularly entranced by the notion that, on some days, da Vinci would stare at his unfinished painting on the refectory wall for many hours, before adding a single brushstroke and going home for the day. Unfortunately, Leonardo decided to use an innovative new technique for his painting, and literally as soon as he had finished it, it began to deteriorate. Over the centuries various restoration methods have been used, and the latest restoration took twenty-two years. Yes, that’s twenty-two years. It’s no wonder they wanted to limit access to the thing. It took Leonardo several years to paint his masterpiece and, by the time I eventually made the reservations, it would feel like it had taken a similar amount of time to book to see it.

‘It looks like it’s quite tricky to get tickets,’ I said to Edith. ‘Do you really, really, really want to see The Last Supper?’

‘Yes. Definitely.’ She did a little flounce of her head to indicate that it was not up for debate.

There were lots of ways we could have planned the timing of the European leg of Road School. We could have gone with the flow and just seen what happened. We could have given ourselves a specific number of days to spend in each location. We could have spent a week in each different country that we visited. But, no: in the end it turned out that our Road School schedule was based around our daughter’s burning desire to see The Last Supper by her hero, Leonardo da Vinci. And this meant that we had to be in Milan at 10.15 a.m. on Thursday 15 May. I seriously hoped that it was going to be worth it.

Born to Run

An early morning mist drifted along the river and seeped over the fields towards our house in a Somerset valley. It was 7 a.m. on a morning in early spring. The sky was clear and blue, although there was a chill in the air. The kids were in the car. The grown-ups were in the car. Everyone had been to the toilet. This was it then: we were setting off on our big adventure. Road School was Go.

‘Have you got the passports?’ I just wanted to be sure.

‘You’ve asked me that twice already,’ Frank said. ‘Did you pack enough tea bags?’

‘Yes. You’ve asked me that already. Let’s go then. We don’t want to miss our boat.’

‘I’ll go and get a few more tea bags, just in case.’ Frank got out of the car and disappeared back inside the house.

I heaved a sigh and leaned over to check that Frank had indeed put four passports into the side pocket of the driver’s door. Then I turned around to check on the kids. They were plugged into their games consoles, busy digging into the pile of snacks on the seat between them. The scent of Quavers hung in the air. The DVD player was showing Cloudy With a Chance of Meatballs. Again.

‘It’s going to be a very long day, and those snacks need to last you the whole way to Amsterdam.’ I used my best teacher voice for the warning.

The kids carried on tapping on their devices and munching on the snacks as though I hadn’t spoken. I sighed again. ‘I don’t know what is keeping your father.’

Edith looked up from her screen. ‘Are we going to miss our boat?’

‘No, it’ll be fine. No need to worry.’ I chewed on a nail.

There was the sound of the front door slamming and the key turning. Frank reappeared carrying a massive carrier bag. He opened the door, leaned into the car and dumped the bag on my lap.

‘Here you go,’ he said. ‘I got a few more tea bags. Just in case. Better safe than sorry when it comes to tea bags.’

I sighed and bit my tongue. ‘Finally. Great. Thank you so much.’ I’d spent hours the night before carefully packing the boot so that all the bags went in and I didn’t have to balance stuff on my lap during the journey.

‘There’s no need to get all uptight about it,’ Frank said. ‘I can put them in the boot if you like.’

‘Can we just go?’ If I let Frank loose in the boot now there would be an avalanche of suitcases. ‘There might be traffic, and we don’t want to miss the ferry.’

‘Are we going to miss our boat, mum?’ Edith piped up again.

‘No, we are not going to miss our boat,’ Frank said. ‘I don’t know why you’re getting so stressed already. We’ve got six months of this. If you’re stressed now, you won’t make it past the first week.’

Alfie looked up from his games console. ‘Mum, did you bring an adaptor?’

‘What did you say? What did you say?’ I’ll admit that I was grinding my teeth by this stage. ‘Don’t you know we’re running late? Don’t you know we’ve got a ferry to catch? Don’t you know they have shops in Europe?’

‘There’s no need to shout, mum,’ Alfie said. ‘Like dad says, if you’re this stressed now, you won’t make it past the first week.’

‘Remember, mum,’ Edith had a smile on her face, ‘keep calm and carry on.’

‘And don’t forget the tea bags,’ Frank winked at me and grinned.

Then he turned the key and the engine of our ten-year-old Audi A6 Allroad roared into life. He backed down the driveway and we set off on the road, windows open and Bruce Springsteen blasting from the stereo at full volume.

The Day the Music Died

We were an hour from home, cruising at a steady speed along the M4, when the CD player started to malfunction. First there was a grinding sound. Then the track started to jump, just as Freddie Mercury was singing at full volume about wanting to break free. Then nothing. Frank signalled left and swerved into Membury services.

‘What are you doing?’ I looked at my watch.

‘I’m not driving all the way to Dover with no music,’ he said.

I groaned. Our car has a stereo that takes six CDs in a cartridge, which is great because it means you get to listen to hours of music without having to change a CD. Unfortunately, the six-CD stereo is located in the boot. The same boot that was currently crammed full with all our gear.

Frank pulled into a parking space in the service station car park and turned off the engine. I jumped out and walked to the back of the car. I opened the boot and stood in silent contemplation. Frank came to stand beside me.

‘Do I have to?’ I said.

‘Yes,’ Frank said. His tone brooked no argument.

‘Mum!’ The cry came from the backseat. ‘Can we go to the loo?’

‘Yes,’ I said. ‘But your father can bloody well take you.’

Twenty minutes later the kids had been to the loo, there was a pile of suitcases on the tarmac behind our car and Frank was wrestling with the stereo, trying to pull out the CD cartridge, but to no avail.

‘Daddy?’ a cry came from inside the car. ‘Are we going to miss our boat?’

Frank ignored the question and turned to me. ‘This cartridge just isn’t going to come out. Not without me breaking the stereo. I’ll have to go to a garage once we get to Europe.’

‘Great. So still no music and I’ve got to repack the boot.’

‘Luckily, though,’ Frank said with the kind of smile he uses when he has done something clever, ‘I brought my old iPod and a mini speaker with me for when we’re in the accommodation. It’s got our entire early CD collection on it – the music of the 1960s, 1970s, 1980s and 1990s. It’ll be like listening to the greatest hits of our youth.’

Frank fished in a suitcase, got out his tech and headed back to the car to set up the temporary music system. I looked in dismay at the pile of suitcases. Then I smiled. What the hell, I thought. Let’s get this party started. I pushed up my sleeves and began to shove our belongings back into the boot.

Highway to Hell

We were on the southbound section of the M25 when I started to worry that Frank might be playing his favourite game: petrol roulette. I peered over Frank’s shoulder to look at the fuel gauge. I tried to do it so he wouldn’t notice. Frank flinched. Damn. I had been spotted.

‘Are we going to run out of petrol?’ I smiled at him.

‘We’ll be fine.’ Strangely, Frank appeared to have taken my innocent question as an accusation.

We drove another few miles. The petrol needle kept dropping.

‘Frank, we won’t be fine. We’re going to run out of petrol. We’re going to miss our ferry. Why do you always have to do this?’

‘Because petrol is much cheaper in France. I have a spreadsheet about this. I can show it to you sometime if you like.’

‘No, Frank, I don’t want to see your damn spreadsheet,’ I said.

‘Language, mummy!’ Edith piped up. (Our family is like an episode of Absolutely Fabulous where Frank and I play the roles of Patsy and Edina, and the kids are both Saffy.)

I turned around to address her. ‘When we run out of petrol, I reserve the right to say to your father, “I told you so”.’

‘You can reserve the right to say whatever you like,’ Frank said, ‘because we’re not going to run out of petrol.’

Alfie looked up from his games console. ‘Stop it, you two.’

As we rolled down the hill into Dover, Frank was coasting in neutral. The petrol light had come on fifty miles earlier – the petrol light that indicated when the car had fifty miles of petrol left in the tank. We eased over the Dover roundabouts on fumes and drifted to a stop at the ticket booth for the ferry. The attendant checked our tickets and waved us through. We cleared passport control and customs, inching along with the engine idling in neutral. Finally, we arrived at lane 52 and pulled to a stop.

Frank turned off the engine and twisted round in his seat. He smiled at the kids. ‘See, I told you we’d make it,’ he said.

‘We’re not in France yet,’ I said. ‘I’m not sure you should have turned off the engine.’

‘All we have to do is drive onto the boat.’

‘And drive off it again. And get to a petrol station at the other end.’

‘We’ll be fine. You worry too much.’

Edith looked up from her games console. ‘Stop it, you two.’

‘Look, this boat has got sockets!’ Alfie could barely contain his excitement. ‘Have you got an adaptor so I can charge my DS?’

It was a French boat with French plugs. The adaptors were buried somewhere deep inside the boot.

‘I am not opening that boot again until we arrive in Amsterdam.’ I had just about had enough of my family already, and I had six months more to go. I took some deep breaths.

‘No need to get stressed, mum,’ Alfie said.

Lorries and cars whizzed past us. We were parked up on the hard shoulder of the E40, which was supposed to be taking us north-east out of Calais towards Belgium. The car rocked from side to side as another giant truck sped by. The hard shoulder was littered with bits of ruptured tyres. But it wasn’t our tyres that were the problem. I grimaced at Frank.

‘I told you so. I knew we’d run out of bloody petrol.’

‘And I knew you’d bloody well say that. So now we’re even.’

‘Stop it, you two,’ the kids said in unison.

‘And will you please stop using so much bad language, mummy,’ Edith said.

Frank got out of the car, heaved a sigh and started to make his way down the hard shoulder in the direction of the nearest petrol station. I watched him disappear into the distance. He had learned an important lesson that day. If you play petrol roulette enough times, eventually you will lose.

Stepping Out of the System

As a parent in the UK, you must make sure that your child has a full time education, once they are of compulsory school age. However, this education does not have to take place in a school. If your personal situation allows, and if you and your children want something different, you can step out of the system altogether. You might do this for a short while, like we did, or as an ongoing commitment to a different way of life. There are all sorts of reasons why people decide to step out of the education system. Some parents do it for philosophical reasons or as a lifestyle choice – they want to spend more time with their children, learning together. Others keep their children out of the system because of dissatisfaction with what they are being offered. Some are making a stand against what they see as excessive government testing. But with an increasing number of jobs no longer tied to a specific location, or to a 9 to 5 working day, home education is becoming a viable option for more and more people. There has been a 65% increase in the number of parents choosing to home educate (or ‘unschooling’) in the UK over the last six years.

Of course, it’s not that simple. If you are going to educate your child at home, or on the road, you will need to ask yourself some important questions:

How long is it practicable for me to educate my children away from school?

What about my job? Finances? Partner? Family? House?

Will it be disruptive to my children, and their school, if I can only home educate them for a short time? Am I being fair?

Do I want to travel with my children, educate them at home, or a mix of both?

What do my children think about this? Are they happy with the idea of being educated outside of school, and how would they like to approach it?

Am I going to do this long term? Do I have access to the right networks and support?

If you decide to home educate your children, you need to remove them from the school roll, by notifying the school. You can apply for a school place again when (or if) you are ready to return. You should note that the school does not have to keep a place open for your child and there is no guarantee that there will be a place for your child in the same school later on. However, your local authority has a duty to ensure that your child has a school place if you request one. If you are only going to home educate your child for a short period of time, some ideal times to do it are when you are:

Moving from one area to another.

Returning to the UK from overseas.

Changing between state and private education, or vice versa.

Moving from a primary to a secondary school.

In these situations, you will be taking your child off roll at one school and registering them at another one anyway. You can simply remove them from school a bit earlier than you would have done and fill in the gap yourself. In England, you must apply for a secondary school place by 31 October, and you will be told which place you have been allocated on 1 March the following year. This means that there is a period in the last year of primary school when you can remove your child from the primary school and still retain their place at secondary school. (And, handily, if this is your goal, avoid Year 6 national tests.) If you choose this option, when you contact your local authority to take your child off the roll, let them know that you still want your child’s secondary school place.

You can also ask your child’s school and your local authority whether they would be willing for your child to be educated partly at school and partly at home. This option is known as ‘flexi-schooling’ and it is sometimes used when a child struggles to attend school full time – for instance, if they have an ongoing illness. However, the school and the local authority do not have to agree to this option. If you decide to put your child back into the school system after a break, share stories of what you did while you were away and let the teachers know how it has benefited your child.

If you are considering home education:

The websites www.home-education.org.uk, www.edyourself.org and www.educationotherwise.net offer a very useful starting point. Tap into the various local networks of support.

For parents in Scotland, the charity www.schoolhouse.org.uk gives helpful advice.

If your child has a special educational need or disability, you must take this into account in the educational provision you offer.

In England, your local authority can make an ‘informal enquiry’ to see whether you are providing a suitable education, but their rights to inspect what you do are fairly limited.

The situation regarding home education varies according to where you live, and you may wish to take independent legal advice to clarify your position. The following links give a basic overview of the legal position:

If you are based in England, see: www.gov.uk/school-attendance-absence/overview and www.gov.uk/home-education.

For Scotland, see: www.educationscotland.gov.uk/parentzone/myschool/choosingaschool/homeeducation/index.asp.

For Wales, see: www.waleshomeeducation.co.uk/the-law.php.

For Northern Ireland, see: www.nidirect.gov.uk/articles/educating-your-child-home. NB: compulsory school age in Northern Ireland is from 4 years old.

The Netherlands

Our House

As we pulled into the campsite on the outskirts of Amsterdam, there were bunnies hopping around in the twilight. This delighted the kids. I think Frank saw the bunnies as a potential source of dinner, though, given the speed at which he drove through the campsite. It had taken me a lot of time and an awful lot of Internet research to decide where we should stay in Amsterdam. I was hoping that I had struck gold with the first booking of our tour.

‘You cannot be serious,’ Frank pulled up to the mobile home and turned off the engine. He turned to me with a troubled look on his face. ‘You booked this? You expect us to stay here?’

‘What’s wrong with it?’

‘What’s right with it, you mean.’ Frank opened his door and got out.

‘I spent a lot of time on Google,’ I said, getting out of the car too. ‘I found out all about accommodation in Amsterdam. And I’m telling you, Frank, this was the best option I could find. It was either this campsite or a pricey hotel in town with no parking, tiny bedrooms, a shared toilet, lots of stairs, no lifts and crack addicts in the hallways. Don’t shoot the accommodation booker.’ Frank raised an eyebrow but wisely kept his mouth shut.

We got out of the car and everyone stretched their backs and shook out their legs. It had been a long journey across England, into France, through Belgium and finally to the Netherlands. What I was now referring to as ‘that bloody petrol incident’ had cost us an hour. We were tired, hungry and ready to collapse into a large comfy bed. Unfortunately, it appeared that we were not going to be spending the next few nights in a large comfy bed. As he entered the mobile home, Frank ducked his head to look into the bedroom. He had to duck his head because the doorways were so low.

‘I’m six foot five,’ Frank said. ‘I can’t sleep in that bed. It’s only five feet long.’

We squeezed though a narrow gangway that ran down one side of the mobile home, alongside the bedrooms. On the other side of the passage was a sink, a fridge and a couple of gas hobs.

‘How am I supposed to cook in a kitchen where two people can’t even pass each other sideways?’ Frank said.

‘I’ll do the cooking,’ I forced a smile. ‘And the kids can do the washing up.’ Alfie and Edith exchanged an incredulous look. ‘This is a lovely big sitting area, isn’t it?’ I moved into the main part of the mobile home and swept my hand around it to indicate the spacious accommodation, like I was Kirstie Allsopp on a European edition of Location, Location, Location. Soon I would be suggesting that we knock down a wall or two and remodel the interior.

‘Mum!’ Edith called from the bedroom. She sounded horrified. I hurried back to see what was wrong.

‘Why are there no windows in our bedroom?’ Edith said.

‘And why does it smell of poo?’ Alfie held his nose.