6,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

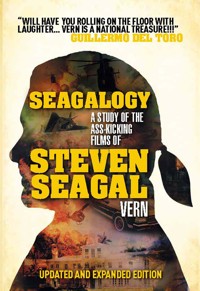

An in-depth study of the world's only aikido instructor turned movie star/director/writer/blues guitarist/energy drink inventor, the ass-kicking auteur Steven Seagal. The hilarious "instant cult classic", hailed by the New York Post, Entertainment Weekly and even Time magazine, is back, updated and extended with 10 new chapters! Brand new material includes Vern's hilarious deconstruction of Seagal's appearance in the Robert Rodriguez movie Machete, and coverage of Seagal's own hit reality TV show, Lawman.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2012

Ähnliche

PRAISE FOR SEAGALOGY

“This book is an instant cult classic” – bookgasm.com

“We can’t believe this actually exists, but the world is certainly a better place for it” – New York Magazine

“It’s as enlightening as it is thorough.” – Time Magazine

“Uproariously funny... the film book I never knew I always wanted to read.” – Nerve.com

“Vern turns his curious love of the oeuvre of aging action star Steven Seagal into a new branch of academia” – Entertainment Weekly

“Required reading. [Vern] analyzes Seagal’s body of work – including energy drinks he endorsed – as if he were deconstructing the Bible” – New York Post

“One of the most compulsively readable film books ever published and I’m not kidding about that even a little bit” – Twitchfilm

“Mind–blowingly comprehensive” – Philadelphia Weekly

“Affectionate, in-depth and often side splitting” – joblo.com

“Perhaps never before has so much effort been expended on a subject of such limited cultural importance. Nor has it been done to such sidesplitting, wrist-breaking, glass-shattering effect” – The Columbus Dispatch

“Seagalogy isn’t a mere work of absurd niche market fanboyism: It’s a definitive text.” – Baltimore Citypaper

As a frequent writer for Ain’t It Cool News, VERN has gained notoriety for his unorthodox reviewing style and his expertise in “the films of Badass Cinema.” His review of the slasher movie Chaos earned him a wrestling challenge from its director; his explosive essay on the PG-13 rating of the fourth Die Hard movie prompted Bruce Willis himself to walk barefoot across the broken glass of movie nerd message boards to respond. (Both events are detailed in Vern’s book Yippee Ki-Yay Moviegoer.) Guillermo Del Toro, the director of Pan’s Labyrinth, called Vern “a National Treasure.” He lives in Seattle.

SEAGALOGY

SEAGALOGY

A STUDY OF THE ASS-KICKING FILMS OF STEVEN SEAGAL

9780857687302

Published by

Titan Books

A division of

Titan Publishing Group Ltd

144 Southwark St

London

SE1 0UP

This updated edition March 2012

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Seagalogy: A Study of the Ass-Kicking Films of Steven Seagal copyright © 2008, 2012 by Vern. All rights reserved.

Cover design by Russell Seal, with thanks to Bryan Thiess.

Visit our websites:

www.titanbooks.com

www.outlawvern.com

PUBLISHER’S NOTE: THIS PUBLICATION HAS NOT BEEN PREPARED, APPROVED, LICENSED OR ENDORSED BY STEVEN SEAGAL, STEVEN SEAGAL ENTERPRISES, OR ANY ENTITY THAT CREATED OR PRODUCED ANY OF THE FILMS OR PROGRAMS DISCUSSED IN THIS BOOK..

The views and opinions expressed by the interviewees and other third party sources in this book are not necessarily those of the author or publisher, and the author and publisher accept no responsibility for inaccuracies or omissions, and the author and publisher specifically disclaim any liability, loss, or risk, whether personal, financial, or otherwise, that is incurred as a consequence, directly or indirectly, from the contents of this book.

Did you enjoy this book? We love to hear from our readers. Please e-mail us at: [email protected] or write to Reader Feedback at the above address.

To receive advance information, news, competitions, and exclusive Titan offers online, please register as a member by clicking the “sign up” button on our website: www.titanbooks.com

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, hacking in with help of old CIA buddy) without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A possible exception would be if you got the written permission to reproduce this publication from an actor who plays a villain in a Steven Seagal picture, preferably Eric Bogosian or Michael Caine. I would also accept Billy Bob Thornton I guess, but other than him it would have to be the actor playing the lead villain, such as Henry Silva (Above the Law) or the #2 in command villain, such as Gary Busey (Under Siege). Thank you.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

Printed in the United States of America.

SEAGALOGY

A STUDY OF THE

ASS-KICKING

FILMS OF

STEVEN SEAGAL

VERN

UPDATED AND EXPANDED EDITION

TITAN BOOKS

NOTE: Some portions of this book were written under the influence of Steven Seagal’s Lightning Bolt Energy Drink (Cherry Charge flavor)

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION by David Gordon Green

INTRODUCTION 2: DARK TERRITORY

GOLDEN ERA (1988-1991)

Chapter 1: Above the Law

Chapter 2: Hard to Kill

Chapter 3: Marked For Death

Chapter 4: Out For Justice

SILVER ERA (1992-1997)

Chapter 5: Under Siege

Chapter 6: On Deadly Ground

Chapter 7: Under Siege 2: Dark Territory

Chapter 7.5: Executive Decision

Chapter 8: The Glimmer Man

Chapter 9: Fire Down Below

interlude: My Giant

[transitional period] (1998-2002)

Chapter 10: The Patriot

Chapter 11: Exit Wounds

Chapter 12: Ticker

Chapter 13: Half Past Dead

DTV ERA (2003-2008)

Chapter 14: The Foreigner

Chapter 15: Out For a Kill

Chapter 16: Belly of the Beast

interlude: Songs From the Crystal Cave

Chapter 16.5: Clementine

Chapter 17: Out of Reach

Chapter 18: Into the Sun

Chapter 19: Submerged

interlude: Steven Seagal’s Lightning Bolt Energy Drink

Chapter 20: Today You Die

Chapter 21: Black Dawn

Chapter 22: Mercenary For Justice

interlude: Mojo Priest

Chapter 23: Shadow Man

Chapter 24: Attack Force

Chapter 25: Flight of Fury

Chapter 26: Urban Justice

Chapter 27: Pistol Whipped

Chapter 28: Kill Switch

CHIEF SEAGAL ERA (2009-present)

Chapter 29: Against the Dark

Chapter 30: Driven to Kill

Chapter 31: Steven Seagal: Lawman

Chapter 32: The Keeper

Chapter 33: A Dangerous Man

Chapter 34: Machete

Chapter 35: Born to Raise Hell

Chapter 36: Deadly Crossing

Chapter 37: Street Wars

Chapter 38: Dark Vengeance

CONCLUSION

APPENDIX I: Other Appearances and Productions

APPENDIX II: Hard To Film: The Ones That Never Made It

APPENDIX III: My Review of Steven Seagal and Thunderbox Live in Seattle

AN INTRODUCTION TO A BOOK

By DAVID GORDON GREEN

It was the Spring of 1988. I was thirteen years old, growing up in Dallas, Texas and coming to terms with life as a pubescent movie junkie. A distinct memory I have is the weekend when the film Above the Law came to the local theaters. I had been primed for Steven Seagal through countless articles introducing him as the next great action hero. This was quite a claim. Could he top Chuck Norris in Invasion U.S.A.? Would he dethrone Charles Bronson from my favorite film Murphy’s Law? Could he channel Sonny Chiba, Michael Dudikoff and Dolph Lundgren in the same roundhouse kick? Unlikely, but my anticipation could not be ignored. Fortunately, the release fell on the same day as the Lea Thompson vehicle Casual Sex and my erection was primed in two directions: sneak into a double feature – hopefully get my eyes on the boobies of the beauty I so admired from All the Right Moves and Howard the Duck and possibly get rocked by the next admiral of Aikido. The day did not disappoint.

Since that awakening as an audience member, I have had the privilege to cheer for Seagal as he dominated the genre. Who wants to see Jean Claude Van-Damme in Death Warrant or fucking Cyborg when you could witness the brutal human elegance of Seagal’s Marked For Death or the astonishing Hard to Kill? His stretch of films that promoted themselves with three dramatic words was for me a trademark and a guarantee that I would be getting my money’s worth (though to be honest, I typically snuck into the movies in the first place – slipping past the “R” rating and ticket price). I suppose for the majority of the American public, Seagal truly arrived with mainstream muscle with Under Siege – Playboy Playmates jumping out of cakes and whatnot – but for me... it was all born in the early flicks, not quite a franchise, but his character was never too far a departure from the last.

A strange tide turned as his fame and fortune grew. Perhaps it was the dazzling spotlight of Tinseltown that prompted a shift in his work. He was no longer studying linguistics and martial arts in the Orient and making intimate action movies. Suddenly, I found myself sitting in front of a slew of message films. Beginning with On Deadly Ground, Seagal began to slip environmental themes, spiritual quests and politics into his films. Perhaps he had lost touch with reality and was living in a vacuum. Where was the soft spoken shitkicker that I gravitated toward in my youth? I was worried that soon I would experience the cramps I felt when I ended my affair with Tom Laughlin’s Billy Jack during his two silly sequels.

Fortunately, as any true movie fanatic, I was able to grow to appreciate his personal crusade. I chose to accept this curveball and take my own enjoyment and expectations to the next level. I began waiting for his films to come out on video and watching them with friends, then soon had no option but to experience his series of foreign financed Direct to Video projects like Black Dawn. I felt obligated to talk to the screen during Half Past Dead and I’m optimistic that Out For a Kill will ferment with age like a fine wine. Through his prolific output, in some way he has become even more interesting. I have returned to watching his films back to back with other films, but strangely paired now with films along the lines of The Kid with the 200 I.Q.,The Englishman Who Went Up a Hill, And Came Down a Mountain, or frequently Troop Beverly Hills.

Through my studies of Seagal, I have come to understand why monks walk before this movie star and throw pebbles at his feet. He is a walking contradiction on a mythical path. Some say he is a douche, while others recognize and value him for his humanitarian work and charitable contributions. He holds the Dalai Lama close, while the mafia wanted to extort him, allegedly. He surrounds himself with German Shepherd attack dogs, but carries around bowls of candy for a sweet accent at the end of a hard day. These are genuine qualities that make this icon so complex. And it is exactly this searing mystique that inspires audiences to roll with his professional transitions and accept his body of work as the portfolio of a soldier lost and found. Seagal’s actual stunt performance may be limited now as his age and death blows have taken their toll. His voice is sometimes dubbed and his silhouette not as sleek, but my enthusiasm for his efforts and entertainment perseveres.

— David Gordon Green, September 2007

David Gordon Green is the acclaimed director of George Washington, All the Real Girls, Snow Angels and the action-comedy The Pineapple Express.

INTRODUCTION 2:

DARK TERRITORY

“You are about to go on a sacred journey. This journey will be good for all people. But you must be careful.”

“Bring people forward into contemplation.” In interviews that’s what Steven Seagal has often said is the goal of his movies. Contemplation.

Now, a lot of people don’t hold Steven Seagal or his movies in the same high regard that I do. So that may seem like a ridiculous statement to some people, especially everybody who is not Steven Seagal. I mean what is there to contemplate about a dude in a ponytail and shiny shirts going around breaking wrists and throwing people through windows? Well, I am not Steven Seagal, but I will try to tell you.

The French invented the auteur theory, the idea that the director can be considered the author of a movie, the one who puts his or her personal stamp on the thing and who deserves most of the credit and blame. But I invented the badass auteur theory. The badass auteur theory is the idea that in some types of action or badass pictures, it is the badass (or star) who carries through themes from one picture to the next.

I mean I agree with the French about the importance of the director, and they also make good bread and were right about Iraq. But in the type of picture we’re going to be discussing in this book it is the star that connects the body of work more than the director. So it makes more sense to compare Above the Law to other movies starring Steven Seagal than to director Andrew Davis’s later best picture nominee The Fugitive.

I think I first developed the theory in discussing the films of Charles Bronson, but I might as well have invented it for Seagal. More than any action star I know of, Seagal puts his imprint on every movie he makes, whether he’s writing and producing it or just appearing in it. He brings a certain personality, formula and set of motifs to pretty much every picture he ever does. Most actors try to find scripts they can work with, Seagal seems to have scripts grow out of him. Seagal once said, “I haven’t always been dealt scripts that were palatable and movies that I thought were even makable, and I think one of the secrets of my success is that I changed them into something that was almost watchable 1.” These scripts are written for him, or by him, or they are rewritten to fit him, so they always end up featuring some of his obsessions: enlightened men with shadowy CIA pasts, westerners with expertise in Asian ways (aikido, swords, herbology, Buddhism), various types of mafia (Italian-American, European, Asian), music (blues, bluegrass, reggae, much of it performed by or written by Seagal himself), the protection of animals or the environment.

And then there’s his politics. From the very beginning his movies have had themes of an out of control CIA trafficking drugs into the country, rogue secret agents turning into terrorists, corporations pillaging the land and indigenous cultures... the types of things you didn’t usually see in action movies at the time, and that you saw a lot more in real life as the years went on. Seagal has admitted that he hasn’t had much control over his movies and has done many of them to fulfill contractual obligations. But he also talks proudly of an “environmental conscientiousness” and “political conscientiousness” he has been able to work into many of his films.

Seagal might be the first to admit that his pictures are often ridiculous, full of corny lines and silly ideas. If so, I would be the second. And I would add that in the case of some of the later films there are many laughable action scenes. Well, boo fucking hoo. I can still say I honestly admire Seagal’s attempts to use his dumb action movies to glorify environmental protection, non-violence, indigenous cultures, intelligence agency reform, Chinese shirts and whatever other hobbies he picks up along the way. (Remember what a surprise it was the first time he picked up a guitar in a movie?)

A lot of people don’t understand how you can take the thematic business seriously when the movie itself is a cocky guy with a ponytail going around saying shit like, “What does it take to change the essence of a man?” But you know what, the Bible has some pretty corny parts in it too. The burning bush? What the fuck was that about? And I never got the part about crustaceans being an abomination. Despite those eccentricities, people still dig on that Bible. Because there’s some good stuff in there and the part with the boat full of animals was awesome. Also the plagues. Yes, I am comparing the films of Steven Seagal to the Holy Bible. Sorry.

A lot of people don’t remember it, or won’t admit it, or most likely never noticed it, but Seagal’s filmography is full of good parts too. If you retrace his footsteps you will find a trail of broken windows and bones. Along that trail will be a series of surprisingly entertaining b-movies and some inexplicably effective big time studio blow ‘em up movies, sometimes in the Die Hard mold. You will find evidence of one-liners both wonderful and hilariously awful. Lines like “I’m gonna take you to the bank, Senator Trent. To the blood bank,” are delivered with such sincerity that I don’t even know anymore if it’s so bad it’s good or so good it’s awesome. It’s like on the old video games, if the score got high enough it would just flip back over to zero and start over. That might be what happened when he said that line in Hard to Kill – it was so bad it flipped over and became great. Or maybe it’s the other way around. I don’t know but the point is, I wish I said that shit to somebody. That was great. Good job Seagal.

Seagal has lived an interesting life. He was the first foreigner to run an aikido dojo in Japan, he broke Sean Connery’s wrist teaching him martial arts for Never Say Never Again, he hosted Saturday Night Live, he was declared the reincarnation of a Buddhist lama, he was blackmailed by the mob and allegedly wiretapped by notorious private eye Anthony Pellicano. There are times when his biographical information has obvious parallels to his work, and is worth mentioning. But this will not be a biography. That is a task worthy of a greater writer than I, one who does interviews and research and crap. I am not that writer and this will not be that book. Instead, this will be a book about the deep study and analysis of the entire Seagal filmography. By watching each of Seagal’s movies in chronological order, cross-referencing their plots and motifs, watching the themes build, the formulas evolve, and the hairline turn into a strange Eddie Munster style widow’s peak, I believe I can come to understand the essence of a man. That is Seagalogy. Join me on this journey, etc.

A quick note before we get started: for better understanding, I have divided the filmography into a distinct set of eras. I got help in naming them from a comic book nerd friend who insisted the early ones had to be “the golden age.” Feel free to define your own eras, but for the purposes of the book here’s how it lays out:

GOLDEN ERA

Above the Law through Out For Justice

(1988-1991)

These four films represent Seagal’s pinnacle as a serious action hero and all the qualities that made him a star. Even if you’re not a serious Seagalogist you should see these films.

SILVER ERA

Under Siege through Fire Down Below

(1992-1997)

These six films (including Executive Decision, in which he takes a supporting role) represent Seagal’s biggest success as a mainstream movie star and what he chose to do with that success. Beginning with the breakout hit Under Siege and continuing through his environmental thrillers On Deadly Ground and Fire Down Below, you get to see him at both his best and his most ridiculous, often at the same time. That’s the yin and yang of Seagalogy.

[transitional period]

The Patriot through Half Past Dead

(1998-2002)

In this period, Seagal found himself making his first direct-to-video film (The Patriot), then triumphantly returning to the big screen with the sleeper hit Exit Wounds. Suddenly he was on video again with Ticker and theatrical again with Half Past Dead, which was not as big of a hit.

DTV ERA2

The Foreigner through Kill Switch

(2003-2008)

In the longest and most productive period of his career so far Seagal made peace with his title as the king of direct-to-video action movies and let loose. He indulged his weirdest tendencies and made some of his most interesting (but not necessarily best) films. He also became far more prolific than before, releasing as many as 4 movies a year. Mainstream acceptance seemed unattainable, plagued as he was with criticisms of his weight gain, increasing reliance on stunt doubles and voiceovers. But he traveled around Europe and Asia making a series of highly distinctive, low budget movies, sometimes even with titles similar to those of his older films. And then he started drinking goji berry juice and playing the blues.

CHIEF SEAGAL ERA

Against the Dark and beyond

(2009-present)

After strictly maintaining his onscreen persona for two decades, Seagal suddenly shook things up by patrolling the streets of New Orleans as a Reserve Deputy Chief of the Jefferson Parish Sheriff’s Office and filming it for a reality show. Suddenly he’s not just in movies, but in half hour episodes that somehow simultaneously humanize him and deepen his mystique. The DTV movies continue (at a slightly slower pace), often showing the influence of his real life police work. This period is distinguished by unexpected departures: a vampire movie, an hour-long drama, a return to the big screen, but playing a villain. At this point, anything can happen. He can fight monsters, he can show up on TV, he can pull you over for driving erratically.

__________

1 Choi, “Seagal flies East” in Impact: The Action Movie Magazine, May 1994, p. 26.

2 My comic book nerd friend wanted to call this “the Kal El Age,” because “Kal El” is Superman’s Christian name and he likes Superman a lot. I told him to go fuck himself.

GOLDEN ERA

1988-1991

CHAPTER 1:

ABOVE THE LAW

“Nico, why is the CIA calling you at 2 o’clock in the morning?”

Most of the big action heroes had to start out small and build their way up. A year before Rocky, Sylvester Stallone was still taking roles like “Young Man In Crowd” in scenes cut out of Mandingo. Arnold Schwarzenegger of course had Hercules In New York as well as bit parts like “Muscleman” in an episode of the TV show San Pedro Beach Bums and “Lars, Gym Instructor” in Scavenger Hunt. Jean Claude-Van Damme not only played an Ivan Drago knockoff in No Retreat, No Surrender, he can also be spotted as a background dancer in Breakin’. Chuck Norris didn’t do much before co-starring with Bruce Lee in Way of the Dragon, but at least in that one he got his ass kicked. Seagal took the opposite route – he started as the star, in one of his best movies, with virtually all the elements of his later pictures already in place. In the martial arts he had climbed the ladder through years of training, but in movies he really was an overnight success.

Directed by future Academy Award nominee for best director Andrew Davis, Above the Law is the blueprint for the rest of Seagal’s career. It lays out his typical storylines, motifs and characters, his Billy Jack-like knack for adding left-ish politics to action movies, his fascination with other cultures, and even the partly fictional backstory that he liked to promote as his public persona. On the other hand, he doesn’t have a ponytail in this one. So in that sense it’s completely different from most of his other movies.

Seagal plays ex-aikido instructor, ex-CIA Vietnam vet Chicago vice-sergeant turned vigilante Nico Toscani. Or, as the trailer narrator describes him, “Nico Toscani – he’s a covert agent, trained to survive in Viet-Nam. He has a master’s sixth degree black belt in aikido, and family in the mafia. He’s a cop – with attitude.” This attitude of his will come in handy when he stumbles across a CIA drug smuggling operation that blows up the priest at his church and plans to assassinate a senator. Like many cops in movies of the ‘70s and ‘80s, Nico gets pulled off the case, but he pursues it anyway. With attitude.

So Above the Law is sort of a cop movie about the Iran-Contra scandal, but more than that it’s about introducing the world to Steven Seagal. He’d been around Hollywood a little bit, choreographing fights for The Challenge and Never Say Never Again, and possibly teaching aikido to the powerful agent Michael Ovitz. But Above the Law was his first appearance in a movie, and he wasn’t just starting out with a starring role – he was starting out with a vehicle. As much as the movie is about a story, it’s about Steven Seagal.

With that in mind, the movie begins by explaining the premise of Steven Seagal. The first image is Seagal’s actual baby photo. The movie opens with Seagal’s gentle voice narrating over a photo montage, as if we’re watching a Ken Burns documentary about his life. He explains that he was born in Sicily but his family emigrated to the US, he grew up patriotic, saw an aikido demonstration at a baseball game and “by the time I was 17 I was there [in Japan], studying with the masters.” It shows real photos of a young Seagal training in Japan and we see that he eventually opened his own dojo.

So now that the movie has established the basic idea behind Seagal, it’s time to demonstrate his abilities. The photo montage segues into new footage of Nico in his dojo, sparring with students. Years later, as Seagal was ridiculed for gaining weight and making silly direct-to-video movies, revisionists would claim that he was not the real deal, that he had never been a very good martial artist and that he only made it into movies because of his connection to Ovitz. But the opening credits alone of Above the Law put the lie to that one. It’s maybe two minutes into the movie and he’s already flipping guys over, waving his hands around at ridiculous speeds and even showing off by speaking Japanese 1.

Next the voiceover explains that Nico’s skills and a chance meeting led to him doing work for the CIA, and there’s a funny montage of the Vietnam War and peace marches with badly dubbed chanting and that type of electric guitar that is supposed to remind you enough of Jimi Hendrix that you know it’s the ‘60s.

So there it is. The American so amazed by martial arts that he moves to Japan, trains for years and against all odds becomes a teacher himself, then starts freelancing for the CIA. This is Nico’s backstory and it’s similar to the background Seagal assigned to himself in interviews at the time. But like the ‘60s montage it’s a combination of real and phony. Seagal is not from Sicily, he was born in Lansing, Michigan. But he really did go to Japan as a young man, he may have really hung around in the general vicinity of the founder of aikido, and later he definitely did run an aikido school, unheard of for a white man in Japan whether he has an attitude or not. However, Seagal’s claims and innuendo about working for the CIA are at best unverifiable. Most tend to write that off as a promotional gimmick. Still, a good chunk of the character of Nico Toscani is the real Seagal, enough that they can share the same photo album on the opening credits. It’s sort of like the approach they use now to turn non-actors like Eminem and 50 Cent into movie stars: create a character based on their real life, and a story based around their abilities, and treat it very seriously.

At the end of the credits sequence there’s a clip of Richard Nixon quoting Lincoln as saying, “No one is above the law, no one is below the law, and we’re going to enforce the law and Americans should remember that if we’re going to have law and order.” This cuts directly to the villain, Kurt Zagon (Henry Silva), on the border between Vietnam and Cambodia during the war, clearly not thinking about the importance of law and order. We don’t know yet that he’s a brutal interrogator and torturer, or that his mission is to get back some missing opium, or that in the future he’ll still be in the CIA and using coke money to fund a secret invasion of Nicaragua. But we still know he’s up to no good. And let’s be honest, it’s obvious that the CIA is corrupt if they’re gonna hire a guy who looks like Henry Silva. I mean look at the guy’s face. Don’t tell me they didn’t know that motherfucker was evil.

And there he is, Nico Toscani, the first ever Steven Seagal character. According to the script, “We see from Nico’s gait that he is athletic, a born leader and totally at home in the jungle.” I’m not sure I really got all that from his gait, but fair enough – he is totally at home in the jungle. He is not at home, however, with these crazy CIA bastards like Zagon. Nico is the naïve rookie who gets upset when he encounters Zagon and other agents doing “chemical interrogation” on some POWs, not for war purposes but to find out who fucked with their opium. At first Nico tries to play along, but his conscience won’t let him. Like Billy Jack before him, he tries to intervene, yelling in outrage “What does this have to do with military intelligence?” and “You guys think you’re soldiers? You’re fucking barbarians!” Which is another way of saying, “Nobody is above the law!” Also he is wearing a cool scarf.

After a brief scuffle he runs off, declaring “I’m through!” as his buddy Nelson Fox (Chelcie Ross) buys him time.

Flash forward to the present day, where Nico is a Chicago cop with a sassy female partner named Jax (the great Pam Grier) and a crying wife (the crying Sharon Stone). Jax is in the middle of her last week on the job before becoming the D.A., so the whole time you’re worried she’s gonna die. And Sharon Stone spends the entire movie crying and whining and trying to get Nico to back down like a coward instead of do the right thing, so you wouldn’t mind that much if she did die.

Like the wedding sequence in The Godfather Part II we meet the whole family because it’s a christening ceremony for Nico’s daughter, and then there’s a big party. We learn that half of Nico’s relatives are cops and the other half are mafia, so they don’t mingle much at the barbecue. It’s not clear in the movie why they included the mafia angle, except that Seagal has a fascination with the mafia. (Years later, ironically, alleged members of the Gambino crime family would try to extort him in real life.) With these connections established, you’d think after the police failed him Nico would go to his mafia relatives for help, but it never happens. The only person that seems to think the mafia relatives are important is the narrator of that trailer. More on this later.

During the party Nico’s mom is crying because his teenage cousin is holed up doing drugs with her pimp boyfriend again. Nico leaves the party, taking Jax with him, telling the family he has to go to work. Then he tells Jax he has to take a piss and he goes into a bar, but instead of pissing he starts roughing up the dudes hanging out at the bar (including Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer’s Michael Rooker, who has one line) trying to find out where his cousin is. This is the first full-fledged Seagal fight scene, and the beginning of a tradition of fights in bars. The bartender (Ronnie Barron) is a memorable loudmouth asshole, yelling “Holy shit man, stop this motherfucker he’s crazy!” But Nico scares him enough that he gives up which room the cousin and the pimp are coking out in. Nico kicks the door down and stages an intervention, shoving the pimp’s face in a table of coke. The guy gets so desperate to not go to jail he tries to butter up Nico by telling him about the “big shipment” he heard about.

When Nico comes out dragging his cousin and the pimp, being yelled at by the bartender, Jax says, “Boy, you got some strange toilet habits!” 2

Before long, Nico, Jax and cohorts are dressed up as meatpackers waiting to bust this shipment. After Seagal’s first big car chase scene (where he holds onto the roof of a high speed car and punches through the side window to grab the driver) they open up the crates and discover that the shipment isn’t drugs, but military explosives. Nico knows enough about explosives that he is able to sniff them and declare, “C-4, m’man.”

Soon he finds himself following drug traffickers to his own church, but he has to let them go because Father Genarro (Joe Greco) starts talking to him and it would be socially awkward not to go into the basement with the man to find out what he has to say about the Nicaraguan, El Salvadoran and Chilean refugees he has stashed down there. Nico is guilted into coming to church the next Sunday, which is when he notices one of the people he followed is in the congregation, and she leaves a bomb. Not exactly the best Sunday to go back to church, in my opinion, but it was good to have Nico there to carry out the bodies.

Like most Seagal movies the plot gets pretty complicated, but unlike the later ones the story unfolds naturally enough that it’s easy to follow. Father Genarro’s friend Father Tomasino (Henry Godinez) has learned through the South American refugees about a CIA plan to kill the senator who’s investigating their activities in Nicaragua. The woman who left the bomb was actually CIA, and she meant to get Thomasino but got Genarro instead. In other words our tax dollars are going to church bombings and they’re not even killing the right padres.

Along the way Nico, of course, is told by his superiors to back off, so he gets mad and kicks a chair. When he stays on the case he gets suspended (a rare “I want your badge and your gun” 3 scene for Seagal) but gets out a stash of guns he has hidden somewhere and keeps investigating.

A reoccurring theme in Seagal movies, especially in the Golden and Silver eras, is the “old agency friend” who either gives him a tip or helps him break into government databases. Above the Law has both – Nelson Fox (despite being corrupt) tries to warn him that he’s in trouble, and a computer expert named Watanabe helps him break into the CIA’s computer files. Watanabe represents the kind of minimalism Seagal usually applies to these characters – we see that she works for some kind of corporate entity because she’s working at an electronics conference, and we can assume since she knows Nico and knows how to break into the CIA’s databases that she used to work for the CIA. But they don’t bother to explain any details because, really, what difference does it make?

In an earlier screenplay some of these details were filled in. Watanabe indicates that she owes Nico because he saved her life once, referring to the time he “kept a few ‘friendly’ tribesmen from cutting my heart out and serving it up as Pad Thai.” The scene is a lot less corny as filmed. Of course it helps that they also cut Watanabe’s line, “If I can’t crack that turkey’s code, it’s time to hang up my rock and roll shoes.” The script even describes “Watanabe working two computers simultaneously, with the gusto of a rock keyboard player,” which fortunately is not how the scene ended up being filmed. When you compare the finished film to the screenplay it emphasizes that Above the Law is so much better than it seems like it ought to be.

But even if it wasn’t, the movie has many good fights and action scenes that helped Seagal to enter the popular consciousness. Seagal fights in a style never seen before on screen, not just because aikido had not been showcased in films like kung fu and karate had, but because he had developed his own system of aikido. According to Seagal student Kent Moyer, “Throughout the entire course of his training and teaching, Seagal’s goal was to develop and refine the ultimate ‘street style’; the most practical combative art for modern applications 4.” Seagal’s fast, blunt style of fighting immediately stands out as an unusual approach to fight choreography. My favorite is the one where a bunch of dudes get out of a car and surround Nico with a gun, two machetes and a baseball bat. It takes Nico about three seconds to get rid of the gun, steal a machete and turn it into a sword fight. He beats them silly and chases the last guy down an alley, scaring the guy so badly he starts to cry and scream “Don’t kill me!” Coincidentally, a very tall acquaintance of the crying man happens to be hanging out on the corner. He sees what’s going on and says, “Hey, that’s my buddy!” He runs over to kick Nico’s ass but is taken down with one punch.

One of the weirdest aspects of the movie is Nico’s relationships with his wife and his partner. In most respects the guy is a saint, looking after his relatives and his congregation, carrying mutilated bodies away from church bombings, hugging the crying women in the hospital, going on missions alone to keep his partner away from danger. On the other hand he seems like a real bad husband, always being cold to poor Sharon Stone unless she’s crying on his shoulder. I haven’t timed it but I bet Sharon spends more than 80% of her screen time either crying, pouting or cowering in fear, saying things like “I’m scared, Nico!” Maybe all that crying practice helped her get her Oscar nomination for Casino, I don’t know. In one of the rare moments of happiness between the two, at the christening party, Nico jokes about Jax wearing lingerie to work, and Jax jokes “Don’t tell her our secrets, she’ll never let you go out with me again!”

For her part, Jax doesn’t seem to have a more important man in her life – she turns down guys who hit on her and complains that she has turned down a hot date to go tail a suspect with Nico. They get dressed up and go to a restaurant and even refer to it as a date. Later in the picture, after Jax is shot in slow motion by Zagon and may die, Nico mourns in the usual movie fashion by looking at photos, including a family portrait of him, his wife, his baby, and Jax! Now think about it. All cops are gonna have close relationships with their partners, but do you think Danny Glover invites Mel Gibson to be in his family portraits? No, not until the end of part 4. I think we all know what is going on here. Nico is cheating on his wife. But maybe Seagal didn’t want to make it too obvious since his real wife might get the wrong idea if she saw part of this movie on cable or something. It’s one of those things you don’t pick up on until you’ve seen the movie a couple times. Which you will.

Another weird aspect is this bartender character. Throughout his career, Seagal will have many fights in bars, but this is the only bartender who will hold a grudge against him and try to come after him. Usually there’s a fight, maybe the bartender says something, but you never see the character again. This guy just keeps showing up. After the fight in his bar, he’s outside trying to convince the other cops to arrest Nico. Later, after the cops have turned on Nico, he’s in the police station filing a complaint about him, and he has a weird way of describing the bar brawl. “He starts doing all this outer space kinda stuff. Puttin my customers in orbit, even.”

Okay so that much is unusual but when it gets really strange is at the end when Zagon gets out of a car with a bunch of dudes and one of them is the bartender! For some reason he gets to hang out and smile sadistically while Nico gets tortured, like he’s getting off on it. I couldn’t figure out how this guy convinced the corrupt CIA madman to let him come along. That outer space story is not gonna be enough, I don’t think. The only explanation is offered in the end credits. In the script he’s called “Bad Dude,” but in the credits he’s “CIA bartender.” I’m not sure how that works that the sleazy bartender is a spook, but there you go.

Seagal himself is not particularly strange in the movie. There is only one little scene late in the picture that gives an indication of what a great weirdo he’ll grow into. He sits at the kitchen table, holding his baby daughter, as his wife and his mom cry and try to convince him that they need to leave town for their own safety. Instead of addressing their concerns, he just says quietly, “You ever notice how clean babies smell – like nothing in the world has ever touched them?” It’s a line only Seagal, or possibly Marlon Brando, could get away with.

Some people have pointed to Seagal’s running in the movie as stranger. There are scenes when he performs a physical activity commonly described as “running like a girl.” I don’t think it’s that bad, though. He looks like he runs pretty fast, at least. You don’t see him chasing guys anymore, so enjoy it while you can.

After you’ve seen the movie a few times, you might start to wonder why the hell they included the detail that Nico comes from a mafia family. They make a big deal about him coming from Sicily, you see his mafia relatives complaining about his cop friends at the christening party, and when he’s being suspended the lieutenant mentions his family as if the apple doesn’t fall too far from the tree. But it doesn’t seem worth all this just as an explanation for why he has “attitude.” Sure enough, the script contained an entire deleted sequence where it all fits together. In the scene where Nico’s wife Sara whines about the need to run away, and Nico talks about the smell of babies, Sara was originally trying to convince him to go talk to his uncle Frederico Larusso in prison. Reluctantly, Nico goes to the prison under the assumed name “Mr. Carlucci.” He confesses to his uncle that he has always hated the mafia but now realizes that they’re not that different from the people he was working for. Uncle Frederico says he knew Nico would come for help and that he had planned not to, but he changes his mind and gives Nico an address to memorize. This cuts directly to the scene where Nico is on the roof and gets caught by Nelson Fox.

It’s weird that they would cut this sequence without finding another story reason for Nico’s mafia connections, but the sequence as it is is pretty useless. It’s not really clear what the address was. If it’s the address to the building he goes to, couldn’t he have found out about the senator’s public appearances and figured it out without the help of the mafia (as he apparently does in the finished film)? And how would his uncle know that address anyway? Not to mention the fact that his plan doesn’t exactly work, he gets captured and tortured while on the rooftop. So even though everything works out in the end it’s not really because of Uncle Frederico’s mysterious tip.

To the Seagal illiterate, this picture is the best bet at explaining why he ever became popular. Although he is not as imposing as in his later, fatter pictures, he moves much faster, his aikido looks convincing and the quickness of the fights make them stand out from other action pictures of the time. The fights are also more raw and brutal than many martial arts films, especially American ones. His style is not as much about looking cool as it is about dispatching opponents as quickly as possible. There is some blood and some graphically broken bones. Nico himself gets pretty bloody too, which doesn’t happen to Seagal much in later films.

In a scenario that would become very familiar over later films, Nico chases some guys into a mini-mart and ends up destroying every shelf or glass surface in the joint beating them down. There’s a classic slo-mo shot where he jumps through the front window using a thug to shield him from the glass. Variations on this stunt will show up in many, many other Seagal films over the years. The scene is an insult to private business owners but a delight to action fans.

Of course, riding on top of cars, throwing guys through windows and turning in your gun and badge are things we’ve seen a million times before. And David M. Frank’s typical ‘80s score (drum machines, guitar noodling and poppin’ keyboard basslines) adds a certain level of cheesiness. But I would argue that, for the genre, this is a high-class affair, nicely directed by Andrew Davis. In the press kit Davis said he “wanted to use the full scope of Chicago as an actual character in the film.” This is, of course, pretentious horse shit, unless he meant Chicago was a bit part character, like the “Hey that’s my buddy!” guy or Michael Rooker. That said, it is a nice setting for the movie and Davis gives the city a more realistic feel than almost any other Seagal film. The streets are always populated. Zagon can be walking into a place to do some business and you can hear some random guys having an unrelated argument across the street. Or Nico can get in a gunfight and you’ll see all the neighbors looking down from the windows of nearby buildings wondering what the hell’s going on.

A lot of the cops seem authentic, too (perhaps because some of them, like Joseph F. Kosala, are retired police officers). The scene where they come to the house to arrest Nico is especially believable. One guy tries to be nice about it, keeps apologizing and saying “we’ll work this out.” Other guys are being assholes and getting in Nico’s face.

Unlike Seagal, Davis had already made a few movies, the most recent one having been the 1985 Chuck Norris vehicle Code of Silence. In 1992, he would raise Seagal briefly to the level of mainstream blockbuster movie star courtesy of the film Under Siege. The next year he’d get best picture and best director Oscar nominations for The Fugitive. I guess it probably made more sense at the time. Anyway, he’s a pretty good director and this is undoubtedly one of his best.

Without a doubt, Davis played a hugely important role in Seagalogy. He is pretty much the mastermind of Chapter One. Not only did he direct, he co-wrote the script with Steven Pressfield, Ronald Shusett and an uncredited Seagal, which means he helped figure out exactly how to showcase Seagal for movies, creating a template for all of Seagalogy.

A good way to see what Seagal’s contribution was is to compare Above the Law to Code of Silence. After all, both are about Chicago cops becoming isolated by institutional corruption while dealing with South American drug lords. Both star a martial artist turned actor and feature Henry Silva playing the main villain. Some of the same actors (like Ron Dean and Joseph F. Kosala) play cops, and even that asshole CIA bartender, Ronnie Barron, is in there playing another loudmouth criminal with a bad hair cut. They have similar Chicago shooting locations, similar Andrew Davis directing style and the same type of cheeseball ‘80s score by David M. Frank.

And yet they aren’t exactly the same type of movie. Code of Silence does not feel like what would become a Seagal movie. Above the Law introduces a lot of new elements to the story that are unmistakably Seagal. First of all, the emphasis on the backstory. Not just because there’s a flashback and semi-autobiographical narration, but because (like most Seagal characters) it’s crucial that he has a past in the CIA. Adding the CIA into the picture is important in itself. The corruption in Code of Silence is isolated: a drunk fuckup cop shoots a kid by accident and plants a gun on him, and the other cops support him even if they know he’s lying. Seagal’s corruption tale is about a thousand times more ambitious since it reaches back to the Vietnam War and has the CIA involved in drug trafficking and plans to assassinate a senator. More novel and more relevant to the time it was made.

You gotta give some credit to Chuck Norris though, in his movie he teams up with a heavily armed police robot, which unfortunately does not happen in Above the Law.

While Above the Law is the template for all of Seagalogy, it is the very first try. So some of the motifs and concepts are in most Seagal pictures even to this day, while others continued for a while but were eventually abandoned. The CIA and aikido backgrounds, of course, turn up in almost every (but not quite every) Seagal film. They’re so common that if a CIA past isn’t mentioned in a Seagal film, you usually assume it’s there anyway.

The theme of corrupt intelligence agencies and the complicated intrigue continue to this day, but the way they’re presented is pretty different. In the early films, they tend to follow Above the Law’s lead by using a monologue or speech where Seagal lays out his feelings about the topic. In later films he still does that occasionally, but it always feels like an improvised bit of dialogue inserted by Seagal to put his fingerprints on the movie, and not a deliberate dramatic moment in the screenplay.

This film has a sense of outrage that eventually disappears from his work. Early on he was able to be more passionate about wrongdoing. Later he will mostly play cynical characters who have seen it all and are hard to surprise.

Above the Law goes out of its way to show Nico’s close relationship to his family, and many of the early Seagal films will have sweet bonding moments to show how much he loves his son or his wife or whatever. Family shit. In the later films, he mostly plays single loners who have little connection to other people, though he often hooks up briefly with a pretty younger woman by the end of the picture.

The vast destruction of glass and glass objects will continue throughout all his films, as will the fascination with Japanese culture. Fights in bars will seem like a requirement for a while but eventually he’ll get tired of that motif and drop it. Same with the “old agency friend” who gives him a tip or helps him out. And speaking different languages. For a while he uses every chance he gets to speak Japanese or Spanish and to do Spanish pronunciations, like when he says “Nee-ca-lrauga.” The hidden cache of weapons will show up a few more times too.

One thing that’s a lot different from later films, he’s much more American here. He’s got the Japanese background but he lives a very American life. I think he was interested in mafia movies, so he put a strong emphasis on Catholicism – the christening, the two Fathers, the bombing in the church. He has a close relationship with the Father and tries to get him to call his mom to say hi. These days, with Seagal so involved in Buddhism, it’s hard to imagine him playing a Catholic at all, let alone making it such a big part of the story.

Even his outfit is all-American: white button up shirt, black suit jacket, blue jeans 5. No Asian shirts or robes. No Asian statues or shrines in his home. Not even decorative swords. Seventeen years later, on the Making of Black Dawn featurette, Seagal will sit in a throne wearing a shiny blue robe and say that his favorite place is Japan and that he considers himself “more Asian than American.” But in Above the Law, Japan has not overwhelmed his identity as an American. It’s just one of the things he’s into. He’s a Chicago cop who happens to know aikido.

Seagal took the politics of the movie seriously, saying in the press notes “This is not a martial arts film. [It] is based on a true story about CIA complicity in narcotics trafficking for the purpose of funding covert operations.” From the opening credits on, it’s clear that this is a political movie. It’s hard to miss the irony of Richard “I am not a crook” Nixon saying that no one is above the law. This is a movie about abuse of power, about government corruption, as well as about shootouts and awesome car chases. I think the Nixon clip signals that it’s a little more serious about its politics than your average action movie. A lot of people tend to lump Seagal in with Chuck Norris, Jean-Claude Van Damme, and maybe on a good day Arnold Schwarzenegger or Sylvester Stallone. But none of those guys were making movies quite like this, especially not with this point-of-view. If their pictures had a political edge, they tended to be about fighting communists, about re-winning the Vietnam War or about having to break through liberal bureaucracies to fight out of control urban crime. Those movies were part of the Reagan years, sharing the worldview of the administration. Above the Law was a response to the Reagan years, calling for an end to some of what was going on.

The screenwriters clearly wanted the audience to see the connection between the plot of the movie and the Iran-Contra scandal 6 that was brewing at the time. In the scene where the sleazy lawyer Salvano meets with FBI Agent Neeley and Neeley gets a call from the CIA to let Salvano’s clients go, the script even specifies that “pictures of Reagan and Meese 7 are prominent on the wall.” If you check the movie, sure enough, there is a photo of Ed Meese on the wall, although the photo of Reagan is cropped out of the shot.

Seagal’s alleged CIA background, if it were verifiable, would’ve lent some extra weight to the movie’s portrayal of a rogue agency. But that extra credibility wasn’t really necessary considering how prominent the Iran-Contra Affair still was in the headlines. The movie was released less than five months after Congress released its final report on the scandal, and less than one month after Oliver North and John Poindexter were indicted on multiple charges.

Even so, the movie was ahead of its time. Most of the media attention revolved around the arms-for-hostages part of the scandal, and how the money from selling arms to Iran was used to fund the terrorist Contra army. It wasn’t until 8 years later that investigative reporter Gary Webb’s “Dark Alliance” series in the San Jose Mercury News revived talk about drug money funding Reagan’s beloved Contra “freedom fighters.” The article (later expanded into a book) didn’t quite describe the scenario shown in Above the Law, with CIA agents themselves running drug empires to fund a secret invasion. Instead, Webb’s work detailed exhaustive evidence of Nicaraguans coming to Los Angeles, supplying cocaine to the new crop of crack kingpins and funneling their profits to the Contras, possibly with the knowledge and wink wink nudge nudge of the CIA. Webb’s series won a few awards but created a firestorm of criticism in the mainstream media. The Mercury News long defended the story but then suddenly turned tail and made a half-assed disavowal. Webb was transferred to a suburban bureau far from his home, effectively forcing him out of the paper. In 2004 Webb was found dead of an apparent suicide 8. The CIA had conducted an investigation on itself and released a two-part report which initially denied any evidence of the claims but then on the other hand described how the CIA had protected more than 50 contras and drug traffickers from federal investigation in order to support the Contra war. Not surprisingly, the mainstream media interpreted the report to mean “innocent of all charges, but guilty of being 100% super awesome,” so many of the newspaper obituaries stated that Webb had been proven wrong.

Above the Law, however, has never been disproven.

Above the Law (Nico in the U.K.), 1988

Directed by Andrew Davis

Written by Andrew Davis and Steven Pressfield (King Kong Lives, The Legend of BaggerVance), story by Andrew Davis, Steven Seagal and Ronald Shusett (Alien, Total Recall)

Distinguished co-stars: Pam Grier, Sharon Stone. Bit part by Michael Rooker (Henry:Portrait of a Serial Killer) as “Man in bar.”

Seagal regulars: Miguel Nino (Chi Chi Ramon) plays a commando in Under Siege. Joseph Kosala (Lieutenant Strozah) plays “Engine Room Watch Officer” in Under Siege. Gene Barge, who plays Detective Harrison, plays one of the Fabulous Bail Jumpers in UnderSiege. Admittedly those ones are really Andrew Davis regulars (he often re-uses the same bit players), but others are definitely affiliated with Seagal. Patrick Gorman, one of the CIA interrogators at the beginning, also plays an oil executive in On Deady Ground. Tom Muzila (one of the aikido fighters in the beginning) plays himself in Hard to Kill and Cates in Under Siege. Another one of the aikido fighters, Craig Dunn, played a liquor store punk in Hard to Kill and a commando in Under Siege. He also did stunts in Out For Justice, OnDeadly Ground and Executive Decision and is in the Seagal aikido documentary The PathBeyond Thought. Haruo Matsuoka is the most impressive of the aikido fighters though because he was in Hard to Kill, did stunts in The Glimmer Man, and even did stunts with Seagal way back in 1982’s The Challenge.

Title refers to: CIA, who think they are above the law.

Just how badass is this guy? In a scripted scene cut from the movie, Jax says, “You don’t wanna catch him without no gun. ‘Cause what he do with his hands... make bullet holes look pretty.”

Adopted culture: Japanese.

Languages: English, Japanese, Spanish.

Old friends: agency buddy Fox (turns out to be evil), cop buddy, computer lady who “has a guy at Princeton” so she can find important files Nico needs.

Fight in bar: yes.

Broken glass: head through cooler and man through window during mini-mart fight.

Innocent bystanders: Seagal punches out “buddy” who tries to intervene with a fight.

Family shit: tracks down cokehead girl to appease crying old Italian grandma, very close with priest, hugs crying wife and mother at hospital, random children wave to him on crosswalk right before shootout.

Infidelity: Closer to female partner than to his wife.

Political themes: CIA trafficking opium and torturing innocents during Vietnam War, police paid off, federal agencies cooperating with drug dealer in “ongoing investigation,” Father Gennaro says in sermon that we need to investigate what our leaders do in our name, Iran-Contra style hearings expose “major intelligence agencies” trafficking drugs, Nico implies that CIA assassinated JFK and RFK, testifies that agencies “manipulate the press, judges and members of our Congress” and are in fact ABOVE THE LAW.

Cover accuracy: Very accurate. It’s a dramatic posed photo of Seagal holding a gun in front of a black void. The tagline describes his background and re-iterates the trailer’s claim that “He’s a cop with an attitude.”

__________

1 Other than explaining his fighting style in later action scenes, Nico’s experiences in Japan are not necessary to the plot. In those naïve days, you had to explain why a dude in an action movie could do martial arts. We’ve come a long way, in my opinion.

2 Seagal characters will have strange toilet habits in other films too, most notably The Foreigner, where he’ll be using a urinal when suddenly he’ll jump out a window without washing his hands or, as far as we can tell, zipping his pants.

3 In an earlier script his superior uses the more slangy “I want your tin... and your iron.”

4 Moyer, Martial Arts Legends Presents Shigemichi Take, Shihan Steven Seagal, The Spiritual Warrior Who Prospered on the Island of Budo, p. 34. Moyer elaborates: “The Steven Seagal style has sometimes been criticized because it does not resemble the soft, impractical Aikido so often seen in America today. In fact, it is a very severe style by comparison.”

5