10,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Elliott & Thompson

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

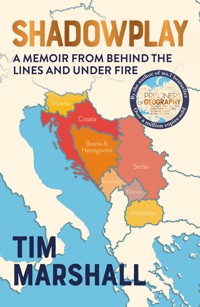

OUT APRIL 2025! The iconic bestseller Prisoners of Geography, updated with brand new content to reflect the changing global geopolitical landscape since it was first published 10 years ago. A gripping eyewitness account of a major 20th-century military conflict by the UK's most popular writer on geopolitics The shattering of Yugoslavia in the 1990s showed that, after nearly 50 years of peace, war could return to Europe. It came to its bloody conclusion in Kosovo in 1999. Tim Marshall, then diplomatic editor at Sky News, was on the ground covering the Kosovo War. This is his illuminating account of how events unfolded, a thrilling journalistic memoir drawing on personal experience, eyewitness accounts, and interviews with intelligence officials from five countries. Twenty years on from the war's end, with the rise of Russian power, a weakened NATO and stalled EU expansion, this story is more relevant than ever, as questions remain about the possibility of conflict on European soil. Utterly compelling, this is Tim Marshall at his very best: behind the lines, under fire and full of the insight that has made him one of Britain's foremost writers on geopolitics.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 445

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Ähnliche

Dedicated to Jakša Šćekić, a Yugoslav who had his country taken away

CONTENTS

Maps

Preface

Introduction

Part One: Before

Part Two: During

Part Three: After

Conclusion

Where Are They Now?

Acknowledgements

Bibliography

Index

About the Author

The regions of former Yugoslavia, before it started to break up in 1991.

Serbian population centres in Kosovo and Albanian population in Serbia. Some of these areas may form part of a land swap between Serbia and Kosovo (see pages 287–89).

Ethinic make-up of the regions that formed Yugoslavia in 1990 (above) and 2015 (below).

PREFACE

THERE HAVE BEEN OTHER WARS, OTHER STORIES, BUT for this writer none like the shattering of Yugoslavia. The end of something political was, for me, the beginning of something personal. It was the first time I really started to understand the nature of war and conflict. It was also the beginning of a physical journey, as my role as reporter at Sky News took me initially through the former Republic of Yugoslavia – from Bosnia to Croatia, Serbia, Kosovo, Macedonia – and then subsequently on to Afghanistan, Iraq, Sudan, Libya, Syria and other places struggling to hold together.

The shattering of Yugoslavia shattered my naive belief that war in Europe was over. During my later journeys, the events and realities I confronted led me to develop a hard realist view of the world. That was tempered only by the finding that wherever there was pain there was also comfort: on all the roads from Bosnia, even in the most difficult of circumstances, I saw the kindness of strangers to those in need.

But still . . . Bosnia was the first conflict to show me that it does not take much for those of ill intent to pour poison into people’s ears and watch them divide from ‘the other’. In Serbia and Kosovo, I learned that ethnic and religious identity will often trump political ideas; that emotion can beat logic. Just as a Serb who would not have contemplated living in Kosovo would still fight to the death to keep the province as his or her own, so an Irish or Italian American, for example, might automatically side with a cause they know little about. In Macedonia, I saw that a quick, sharp and well thought-out foreign intervention can work to pull two sides back from the abyss.

Later, Iraq provided a different instruction: that a long, poorly planned intervention could open the way to that abyss. And yet through all of those subsequent conflicts, my mind would always return to Yugoslavia – the place where I learnt that the phrase ‘mindless violence’ was rarely correct. There was so often a cold, evil logic behind some of the worst behaviour.

Yugoslavia was also a place I learnt to love for its natural beauty, its music, the tough, often deadpan humour of its people, and their astonishing levels of education and knowledge of the outside world. As the man to whom this book is dedicated said: ‘Ah, Yugoslavia – it was a good idea.’

I first wrote this account of the Kosovo War in its immediate aftermath, and it was originally published in translation in Serbo-Croat in 2002. Twenty years on from that conflict, I realized that the story was not yet finished. So here it is, in English, with new opening and closing chapters and new maps. The original text is almost untouched – just tidied up in parts where it was apparent it had been written under the influence of exhaustion, alcohol and a rebalancing of reality after returning home from almost two months in Afghanistan.

The political story remains more important than the personal, though this book is a mix of the two. I hope that, through the less important one, the other is well told.

INTRODUCTION

‘Life can only be understood backwards; but it must be lived forwards.’

Søren Kierkegaard

THAT WAS THEN. THIS IS NOW.

Then, we had bombs and bullets, followed by despair and demonstrations and, finally, revolution. From the burnt ashes of the parliament building in Belgrade, a modern state was supposed to rise and take its place among the community of European nations. The past would stay in the past, not become a barrier to a bright future. Now, two decades on, this remains a work in progress. The past is in danger of once again becoming the present.

Back in 1991, it became clear that Yugoslavia was breaking up as the country accelerated towards disaster. After losing Slovenia, Serbia’s President Slobodan Milošević unleashed the might of the Serb-dominated military onto first Croatia and then Bosnia and Herzegovina to prevent them from following suit.

As the situation escalated, the Europeans told the Americans, ‘It’s OK – we’ve got this.’ Luxembourg’s Prime Minister Jacques Poos said, ‘This is the hour of Europe’; Italian Foreign Minister Gianni De Michelis claimed there was a European political ‘rapid reaction force’; the EU Commission president Jacques Delors said, ‘We do not interfere in American affairs. We hope that they will have enough respect not to interfere in ours.’ The US seemed happy to sit this one out, as Secretary of State James Baker responded, ‘We do not have a dog in this fight.’

After four years of complete failure by the EU to halt the mass bloodshed, the Americans found their dog and stepped in. They bombed the Serbs in Bosnia, forced Milošević to the table and constructed the 1995 Dayton Agreement which bandaged the open wounds the wars had caused. But the US and the EU then took their eyes off the Balkans ball again as the Serbian province of Kosovo slid towards conflict, which finally erupted in 1998.

Milošević, clinging desperately to what remained of Yugoslavia, was never going to allow the Serbian province of Kosovo to leave. It may have been overwhelmingly dominated by ethnic Albanians, but it was also the cradle of Serb civilization. Clashes between the Kosovo Liberation Army (KLA) and the police intensified, with civilians on both sides being killed. Milošević again sent in the military, and the following year NATO came in on the Kosovars’ side. For three months Serbian targets were bombed from the air across the length and breadth of the country. By the time Belgrade’s military was forced out of the province, more than a million Kosovar Albanians had been displaced and up to 14,000 killed. Hundreds of Serb civilians were killed in the NATO airstrikes and up to 200,000 were displaced.

Today, the Balkans continues to simmer. Serbia and Kosovo in particular remain hostile to one another and war between them is not unthinkable. In 2018 when Kosovo announced plans for an army, Belgrade responded with the threat of war. In the same year Serbia blocked Kosovo’s entry to Interpol. In response Kosovo imposed a 100 per cent tax on imports of Serbian goods and accused Belgrade of ‘numerous acts of provocation’. One example was when a train decorated with the Serbian flag and signs reading ‘Kosovo is Serbia’ attempted to enter Kosovo; it was turned back at the border.

In this atmosphere both sides are considering a land swap to resolve some of the tensions between them, but this massively emotional and complex situation will require huge compromises. It is of course possible this would lead to a real peace, but there is also a danger that it would spark a wider war, opening up the wounds of the past.

Twenty years on, territorial disputes are also rife throughout the region, so, what if trying to solve the Kosovo problem via land swaps creates others elsewhere? The Serbs in Bosnia might step up efforts to join their territory, Republika Srpska, into Serbia proper, a move which would be supported by those in Belgrade who still believe in a ‘Greater Serbia’. The Albanians of Macedonia, kindred spirits of the Kosovars, might reignite their 2001 military effort to create a separate state. In turn, both Kosovans and Macedonian Albanians might wish to merge into a ‘Greater Albania’. It follows that if the above scenarios came to pass, then what was left of Macedonia would fall prey to division as Serbia, Greece and Bulgaria scrambled to protect their interests. These are indeed ‘ifs’ and ‘mights’, but given the history of the region over the past 120 years, they are more than plausible.

And there are other tensions in the area that could escalate the problem. Progress towards EU membership for Bosnia, Serbia and Kosovo has stalled. Organized crime plagues all three areas. Bosnia and Kosovo have small networks of extremist Islamists that have grown as jihadists have returned from the Middle East, and there are many extreme nationalists in Macedonia, Kosovo, Republika Srpska and Serbia who would seek to pour fuel onto any small fire which broke out in hope of a bigger conflagration. In the 1990s it took years before the EU and NATO intervened to quench the flames, and that was when international armed forces had a much stronger presence. But as the Balkan conflict zones became relatively stable, foreign powers drew down their military power. At one point, there were 80,000 troops involved in Bosnia, now the EU Force has just 7,000. In the current climate, with so few troops in place, and after the disasters of intervention in Iraq and Libya, the USA and the EU might hesitate even longer to escalate.

On the positive side, relations between Croatia and Serbia are cordial, cross-border trade is increasing and, even if the populations still cannot be described as friendly towards one another, Serbs once again sun themselves on the beaches along the Dalmatian coast. There is also a free trade agreement (CEFTA) signed as long ago as 2006 which has helped bind the wider region together incorporating as it does Croatia, Macedonia, Montenegro, Serbia and others. This has boosted economies and doubled exports to the EU. Two of the former Yugoslav republics, Croatia and Slovenia, are now integrated members of the EU, and Serbia became a candidate country in 2012, although without resolution of the Kosovo question that is what it will remain.

As for becoming a modern liberal state in the cultural sense, Serbia still has some way to go. According to Human Rights Watch, attacks on minority groups such as Roma, Hungarians and ethnic Albanians are commonplace and there seems to be a reluctance at both state and societal level to deal with discrimination. Same-sex marriage was legally prohibited in 2006 when Article 62 of a rewritten constitution explicitly defined marriage as being between a man and a woman. Gay Pride marches have repeatedly been attacked by ultra-nationalists to the extent that cars and buildings have been set on fire, and thousands of riot police are required to protect participants in what is a routine event in many European countries. A gay woman, Ana Brnabić, was appointed as prime minister in 2017. However, critics argue that this was simply an empty gesture by the nationalist government to show other EU countries that it was falling in line with their values, rather than a sign of actual progress.

Serbia is indeed a multi-party parliamentary democracy with competitive elections and a vibrant intellectual and cultural society. But it remains deeply socially conservative and in recent years the government has been eroding political rights, as well as trying to restrict media and legal freedoms.

This partially explains why anti-government demonstrations broke out in late 2018 and continued into 2019. Other European countries took little notice of this, or the increasing cross-border tensions, preoccupied as they were with Brexit, the Gilets Jaunes and Catalonia, among other things, but down in the Balkans things were once again stirring.

The demonstrations in Belgrade were visibly similar to those against Milošević in another time. Tens of thousands of people, marching, blowing whistles, week after week, month after month, often in the freezing cold, hoping for a change for the better, but fearing the worst.

Twenty years ago, the slogan on the streets was ‘Gotov je!’ (‘It’s over!’). Echoes of those heady days and nights are now heard in the chant of this new generation of Serbs: ‘Pocelo je!’ (‘It has begun!’). In March 2019 demonstrators broke into the state-run Radio Television of Serbia building, demanding to address the population live. The last time this happened was in 2000 during the final assault on the Milošević regime.

This is now – what follows was then . . .

PART ONE

BEFORE

CHAPTER 1

‘I know of no safe depository of the ultimate powers of the society but the people themselves, and if we think them not enlightened enough to exercise that control with a wholesome discretion, the remedy is not to take it from them, but to inform their discretion.’

Thomas Jefferson

‘YOU CAN’T COME ALONG,’ I SAID.

‘I’m coming,’ was the reply.

‘You can’t come,’ I repeated.

‘I have to come,’ said Jakša, glaring at me across the table on the terrace of the Grand Hotel in Priština. It was an autumn evening in 1998, the weather was warm, the beer was cold and the conversation was almost as heated as the war between Serbia and the KLA which had exploded that summer. Both sides were committing atrocities, both sides were sure of the justness of their cause, both peoples would eventually lose, but not before a lot of them had their lives, and some their bodies, torn apart.

‘You’re not coming,’ I repeated. Sky News producer Jakša Šćekić was insisting that if I was going to go out and play, then so was he.

‘I have to come.’

We had arranged to go on night patrol with the Serb police out in the badlands where the KLA lived. It hadn’t been done by the foreign media and was a chance to really show what it was like out there once the lights went out and things got scary. I didn’t want Jakša along, as we all knew it might be a little sticky. I had to go to do the report, cameraman Fedja had to come for obvious reasons, but what was Jakša going to do if we came under fire? Brief me on the Battle of Kosovo Polje in 1389? Take notes?

We had been working together for five years, Jakša and I, and had become good friends. I admired his knowledge, wisdom and honour. He admired my naivety, foolishness and lack of ability to pronounce even simple words in what he called ‘Serbo-Whatnot’.

Saying ‘Serbo-Croat’ had become politically unacceptable about seven years previously when the Croatian War of Independence broke out and Yugoslavs really began to divorce. Some partners argue over children and houses. The Yugoslavs argued over lives, and paid with them. They killed children and burned houses for good measure. All sides committed war crimes by any definition. Tragically, for so many of the people left behind, the most important question remains ‘who killed the most?’ Then they begin to argue about it and so the circle continues. You can have the same conversation in Bosnia, Croatia, Serbia and Kosovo, and hardly anyone will ask what is really important, the question the Germans asked themselves after the Holocaust: ‘How can we stop this from happening again?’

On that balmy late-October afternoon I had a more mundane question and I kept on asking it.

‘Why do you have to come?’ I demanded.

‘You’re not allowed to ask stupid questions until it’s dark,’ replied Jakša. It was a rule we’d agreed on years before when I’d first launched into a torrent of questions about Chetniks, Ustaše and Bosniaks before we’d even finished our breakfast coffee. I thought I knew my history, but actually coming to a region where everyone seemed to have a grievance and an ‘itch’ at the end of their name was confusing. Milošević. Panić, Ilić?

‘Jakša!’ I shouted. ‘Why do you have to come?’

He looked at me for a few seconds and then with a completely straight face replied, ‘Because I have to record your final words.’

At dusk we loaded up the white armoured Land Rover with the TV kit, cigarettes and beer for the police unit, and our flak jackets. None of us usually wore them as they slowed us down, but we always carried them in the vehicle. I was in the back, Fedja and Jakša sat up front.

Mid evening found us under a beautiful starlit sky, on a deserted country road, and in a panic. We’d taken a wrong turn and by doing so reminded ourselves of why most people hadn’t bothered to do the night story. It was too easy to stray into KLA territory. Fedja and Jakša were muttering to each other in Serbo-Whatnot. The only thing I understood was UCK, Serb for KLA. With two Serb journalists murdered by the KLA and four kidnapped, Fedja and Jakša were now where they didn’t want to be, behind KLA lines. Fedja stopped the engine and killed the lights. The windows on armoured cars don’t come down so he opened the door and we listened for a few minutes. At night you can hear for miles across the plain, which leads from Priština to the Prokletije – or ‘Damned Mountains’ – that divide the Serbian province from Albania. A dog’s bark carries across the villages and hamlets. Gunfire can make you jump at more than a mile away.

There was silence, but we knew that within a couple of miles were several KLA units and their Serb counterparts. Both would have heard our engine and neither would have known who we were. I began by thinking, ‘Well, I’ve read about Western journalists being with their local counterparts when the locals get shot, but it wouldn’t happen to Jakša and Fedja because they’re friends of mine.’ Then, a second later thinking, ‘Idiot. To the KLA, many of whom have seen their families killed by Serbs, it is entirely irrelevant that the two Serbs they’ve just got their hands on are friends with some British bloke they’ve never heard of.’ Five minutes after my friends understood the situation I also realized that driving around with Serbs, in the dark, behind enemy lines, with gangs of raging madmen with guns all over the place might not actually be such a good idea. I suddenly agreed with Jakša’s opinion of me. Maybe I was just another glupi international novinar (‘stupid foreign journalist’) who he had to explain everything to. There was a private opinion among the domestic Belgrade media corps that too many of the foreign journalists thought the most important thing about the story was that they were covering it. The TV journalists were the worst – on one famous occasion a well-known British reporter shouldered an army medic out of the way so that she could be filmed ‘caring’ for a wounded civilian.

Along with the rest of Europe I had watched on TV in utter horror at what was happening in our continent. To my generation it just didn’t seem possible. War was what happened far away, in places with different cultures. War did not happen in our continent because we’d left all that behind. War certainly didn’t happen in Dubrovnik. Surely that wasn’t allowed in places where we had been on holiday? But by 1991, people in Germany, France, Italy, Sweden and the UK were watching the evening news and saying, ‘Oh look, that wall that’s just been blown up in the harbour is near the hotel we stayed in.’ Nor did wars break out in cities where you could stage the Winter Olympics, such as Sarajevo. Then it happened. As different regions began declaring independence, the Yugoslav government tried to prevent the break-up of the country; the tanks rolled into Slovenia, Croatia went up in flames, followed by Bosnia. The images from the siege of Vukovar in Croatia looked like a Second World War battle on the Eastern Front.

You either ignored it, became confused or did a crash course in South East European history. Finally the pictures, which for us were only familiar from Pathé Newsreel, reached their mad but logical conclusion with the expulsion of an entire people based on their ethnicity. The echoes of the Holocaust came through the screens – they were faint, but this was the closest Europe had come in the half-century since the Second World War.

‘Let’s go,’ said Fedja. Without turning the lights back on he did a nine-point turn in the dark, crashing the gears, revving the engine and at one point even managing to briefly hoot the horn. He made so much noise the KLA must have wondered why the Serbs were taking their driving lessons so late at night. It wasn’t Fedja’s fault; he actually knew how to drive these things. The armoured cars the media drive tend not to have power steering. Instead, whoever kits them out with steel plates also appears to fit some sort of sticking device which prevents the wheel being turned in any direction more than about one inch at a time. This is a shame because it’s not what you want in the situation we were in. What you want is a tank.

As none of the major media companies had yet hit upon the idea of buying a fleet of T-92s as company cars, we were stuck with the armoured variety. Fedja beat the gear stick to within an inch of its life and we trundled back along the road in the darkness and turned off into a lane. If it had been mined we would have been in trouble, as we wouldn’t even see the ones which were sometimes left on top of the tarmac ahead of a roadblock.

After another turn, we were back on what passed for a decent road. We crawled along at about 5 miles per hour for a few minutes, then pulled into what I could just make out was a petrol station. Fedja turned the engine off and lit each of us a cigarette. We sat and smoked in silence for a minute.

‘What’s going on?’ I said. It was after dark so I was allowed to ask stupid questions.

‘Just wait,’ said Jakša. We sat for a couple more minutes in total silence. Then I noticed moving out of the shadows a tall man dressed in black from head to foot. He carried a Kalashnikov and had the air of an experienced front-line soldier. Jakša and Fedja obviously knew he was there, and I quickly assumed he was a Serb, which on this occasion was a good thing, as I didn’t fancy the alternative. Without saying anything, he simply pointed at us, and then at the ground. We slid out and followed the man back into the shadows by what was left of the walls of the petrol station. I noticed they were shot and shelled to pieces, there was no glass in the windows and there were bullet casings on the floor. ‘Incoming and outgoing,’ I thought. No wonder the soldier’s colleagues were all smoking.

I joined them in a Marlboro Light and affected an air of nonchalance as if I spent most of my evenings like this. They were not just a very tough bunch of guys, they were also not stupid. One took the cigarette out of my mouth, cupped it in his hand and said, ‘Hold it like this so the glow doesn’t show, that way they’ll take longer to zero in on you.’ I remembered the only First World War story my grandfather ever told me despite his having spent four years on the Western Front: ‘They used to notice the first cigarette being lit, they took aim with the second and they killed the man getting the third light.’

Snipers. Everyone was talking in whispers so I whispered to Jakša, ‘How far away are they?’

‘About 400 yards,’ he replied.

‘Mmm,’ I thought, ‘that’s quite a long way away in the dark.’

As if he was reading my mind Jakša then added, ‘And they’ve got night sights.’

The officer in charge explained that a large unit of about thirty KLA men was in a copse, 400 yards away, up a slight incline. The previous night his unit had been involved in a firefight in which three of his men had been killed. Therefore, he said politely, it was too dangerous for us to stay. Jakša argued with him for about three seconds before the guy’s patience ran out and he ordered us ‘glupi novinar’ to get back into our ‘glupi novinar glupi vehicle’ and ‘fuck off’ as we had already attracted enough attention.

They were a ‘special police unit’, not necessarily the type of Serb MUP (Ministry of Internal Affairs) Specials which had carried out so many of the murders that year but ‘special’ in that they were soldiers. They were a Yugoslav army unit in a forward position which was supposed to be guarded by the police. It was the only way the Yugoslavs could compete militarily with the KLA under the terms of the ceasefire just negotiated by Richard Holbrooke, and naturally they took it.

Holbrooke was a US special envoy, and the man who three years earlier had put the ‘Dayton’ deal together which brought a form of peace to Bosnia. His forceful character had led the American press corps to dub him ‘The Big Swinging Dick’. With the number of atrocities growing in Kosovo the United Nations had passed Resolution 1203, demanding that Serbia comply with previous resolutions and cooperate with NATO and OSCE (the Organization of Security and Co-operation in Europe) ceasefire-monitoring officials. The resolution was passed under Chapter Seven of the UN charter, meaning it could potentially be enforced with military action.

NATO was now threatening to bomb, unless the Yugoslav Third Army based in Kosovo remained in barracks and the MUP Specials left the province. With things on a knife-edge, Belgrade had already begun to comply and was scaling back.

The ordinary police units would not be able to carry heavy weapons such as machine guns or mortars. The trouble was that the KLA weren’t part of the agreement, although they had agreed a ceasefire. The ceasefire was a fiction. It didn’t matter how much the diplomats said it was holding; everyone, including them, knew there were shooting, bombing and mortar incidents every night and, occasionally, during the day. It was difficult to tell who had done what, or fired first, amid the welter of propaganda from both sides. Whoever was to blame, each side tried to ensure it had the best weaponry it could get away with.

The outside world had an idea of what was going on. The Americans were using their spy satellites to monitor movement on the ground, while the British did more of the human intelligence. An MI6 officer was living in Priština at the time, backed up by a Foreign Office diplomat. The diplomat wasn’t a spy, but we all knew that his reports ended up on more than just one desk in London. Up in Belgrade another team was used to gather the political information. According to an MI6 source, ‘we had one man in the embassy who never left it. His job was to sit in a room with a pair of headphones and listen to Belgrade. Mostly it was hard-wired telephone lines, that had been going on since before mobiles came in, so the monitoring of mobiles was left to GCHQ in England and Fort Mead in the States.’

An MI6 communications specialist told me later that GCHQ listened to just about everyone, including people on their own side: ‘They used to get exasperated with Robin Cook [British Foreign Secretary at the time]. They sometimes listened in to his mobile conversations and he didn’t appear to understand that he was saying things he really shouldn’t. Mobile phones? They’re like microphones so if you don’t want it broadcasting don’t say it.’

Naturally Serb intelligence was also playing the game. They had taken an apartment opposite the British embassy. It was useful to photograph whoever went in, and for attempting to listen to the conversations inside. The really sensitive conversations were held in a secure room, swept for bugs and protected from the type of equipment that can hear through walls. Even so, for the Serbs it was worth picking up snippets of the sort of talk that goes on in embassies even outside of what they called ‘The Deaf Room’.

The British ambassador between 1994 and 1997, Sir Ivor Roberts, was aware the Serbs were listening: ‘Sometimes you can play that to your advantage by getting your message across, and sometimes you can use it for misinformation.’

After Dayton the British had gone down to just two intelligence officers in Belgrade and at times just to the ‘Head of Station’. The crisis in Kosovo had led to an urgent review, and a planning team had been put together which liaised with the Foreign Office and army intelligence. Members of both teams would end up in Kosovo a few weeks later disguised as civilian monitors to ensure that the sort of unit we found at the petrol station could no longer operate, but they would also have many other tasks.

We left the ‘specials’ at the station and found the main road back towards Priština. We could see the lights of the town a few miles away as we pulled up to what was supposed to be the furthest checkpoint the Serbs were allowed to operate outside of the capital. Of course they had units further forward but this was the last official one, and we had permission to film there.

If we had reported the make-up of the unit on the hill it would have led to the Serbs arresting Jakša and expelling me on the grounds of giving away military secrets. Six years of covering conflicts in various parts of the world had taught me which lines to step near but not across. Eventually Serbian newspapers would describe me as a ‘Balkanski Ekspert’, but that was some way off, and even then it wasn’t true. I was also called an MI6 agent and ‘more than just a friend’ of paramilitary leader Arkan. That wasn’t true either, but the inevitable connections between intelligence officers, journalists and politicians meant you were often operating in a hall of mirrors. Journalists invariably bump into spies because they work in the same areas. The spies pretend to be diplomats, business people or a range of other things. Sometimes each party knows that the other knows all about them, but it’s only polite not to mention it. Meanwhile, the politicians are having similar conversations. A combination of ‘spooks’, ‘journos’ and ‘politicos’, added to ‘the people’, would eventually lead to the overthrow of the president of Yugoslavia, Slobodan Milošević. At this stage he still had a way out. The coming months would box him in, but in the end he virtually gift-wrapped and posted himself first class to a small prison cell at The Hague. MI6 and the CIA helped, but so did Milošević and his own people. It took some time to work out how, but with ‘Slobo’ gone, the secrets began to emerge.

The checkpoint was situated at a crossroads. There were two bunkers made from sandbags and a couple of shot-up buildings, with fields on all sides and a solitary street lamp. They were ordinary cops, in fact very ordinary. Not at all like the army men facing the KLA on the hill, who were front-line soldiers with experience in Croatia and Bosnia. I was now with men who knew just a little bit more about warfare than I did, which is to say not very much. This thought made me feel a little exposed. There were just six of them. Two were patrolling the area, or rather patrolling about fifty yards in any direction because after that it was too dangerous. This was not why these young men and the others all over Kosovo had joined the police force. Until a few months ago they’d been quite happy back in their Serbian home towns catching burglars, issuing speeding tickets and taking the occasional bribe.

Now they were over here, underpaid and overstretched. Every night some ‘crazy Shiptar’ [derogatory term for Albanian] was shooting at them and they were shooting back. They were not about to go looking for trouble. I got the impression that they were rather hoping trouble would pass them by. They were nervous about cars, because in the past KLA men in civilian clothes had pulled up and thrown hand grenades into the bunkers. They were nervous because they didn’t have machine guns, bulletproof vests or night-sights to see in the dark. Ask police officers in Manchester or Milan to take on a guerilla army and they might do it, but only if you give them the necessary weapons. These six didn’t even have much experience. Their position was less a checkpoint and more a target. It seemed crazy that they were being left out there to be shot at. They were paying the price for the terrible crimes committed by various units of the Serb state.

I was lying in the middle of the road, staring at the night sky and looking like an idiot. I had put my back out two days earlier when the armoured car went over a pothole. My head had connected with the roof of the Land Rover and a second later the bottom of my spine had connected with the wooden bench I was sitting on. The only way to relieve the discomfort was on my back with my knees up. The twanging nerves were worse than the thought of my hurt pride so I lay down in the middle of the road, with everyone else crouched behind the sandbags. Meanwhile unbeknownst to all of us, a KLA unit was approaching stealthily through the fields.

The police, not knowing who was a few hundred yards away, thought the sight of this ‘glupi Engliski novinar’ lying on the road so amusing that they forgot they thought all foreign journalists were lying scumbags who lied for breakfast, lunch and tea – and who were part of the international conspiracy against Serbia. We got on fine, and I was spared the finger-inthe-chest routine.

In the top left-hand side of my chest I have a slight indentation. This has got progressively deeper as the years have gone by. Many outsiders who have worked in the Balkans also bear the mark. It was caused by officials who worked for the Belgrade regime. They, or their supporters, would poke you in the chest while saying ‘You (prod) people (prod) don’t (prod) understand (prod prod).’

There wasn’t much you could say to that, especially as the person saying it usually had some sort of weapon to use against you. It was either a gun, a permit to go somewhere, or a visa stamp. Whenever it happened you had a choice. You could remind the person with the weapon about the atrocities carried out by Serb forces. The response would be greater anger, followed by a list of all the atrocities carried out against Serbs. You would then be in physical danger if they had a gun. You would be in danger of not getting your story if they controlled a checkpoint, and in danger of not even getting into the country if they were in charge of visas.

Or you could simply take the finger and allow it to make the indentation a little deeper. I had a simple rule. If they had a gun, agree with them. If they can let you past so you can do your real job, take the finger in the chest. If it’s a senior official in the embassy or the government and it means you’ll get a visa then take the finger but tell them, ‘I understand what you are saying, but I am not on your side.’ It was a good rule and it helped me the following year when, during the NATO bombing, members of the Yugoslav government tried to flatter me into sympathetic coverage of their side of the story.

Taking pity on the foreigner with the bad back, our new friends at the checkpoint allowed us to go with them to patrol the fifty yards in any direction of Kosovo they controlled at that point. Before we’d set off that evening I’d had images of walking through woods and across fields on patrol. These guys were reluctant to leave their bunker.

Fedja and I crept around a wheat field following an unenthusiastic policeman as he rustled through the stalks. The only person who could see anything was Fedja. He had the night vision lens on his camera and so while our world was black, his was green. The night-sight works by picking up any source of light and magnifying it. The stars were out so he could see several hundred yards ahead. The police, on the other hand, were stuck in the middle of nowhere, under-equipped, possibly surrounded by the KLA and even the bloody journalists had better kit than they did.

We returned to the bunker, I lay down on the road again and looked up at the stars. The Balkan night sky in the countryside, in all its majesty, can rival the best. The air is clean, untainted by neon, and is so overwhelming you can quite forget about such stupid things as bunkers and bullets. I breathed in the cool night air and listened to the silence.

Suddenly, something went bang in the night. The sounds of heavy bursts of sustained gunfire made me leap up and into the bunker. Fedja, Jakša and the policemen were all quite relaxed as the firing was coming from up the hill at the petrol station. Fedja was already filming with the night sight which could pick out the contours of the hill and the trees on it, but even with the naked eye we could see what was going on.

From the tree line, the KLA were pouring fire into the disused petrol station, and the soldiers were returning fire at the same rate. The tracers flew across the gap between them. Tracer bullets are often used at the rate of one in every twelve. It looked like constant streams of light in a dotted line flowing between them. What made it even more frighteningly impressive was that in between each dot were another eleven bullets. The tracers were orange because that is one of the easiest colours to see in the colour spectrum. The lines swayed a little as they spat across the gap. When a soldier fires a Kalashnikov set to automatic, or a machine gun, even a fast-beating heart can cause the aim to waver slightly. The heavier thudding sounds were a machine gun, while the Kalashnikov assault rifles made a higher cracking sound.

On the police radio we could hear the officer we’d met asking for assistance. ‘We are taking fire and are outnumbered,’ he said calmly. His request for an armoured personnel carrier to be sent was denied by some chief, somewhere, on the grounds that it was too dangerous to go up that road until dawn.

After a few minutes the firing subsided. There was the occasional crackle of a short burst, then just a few single shots now and then. The men at the station were a far better fighting unit than their opponents but there was no way at the moment they could take the fight to the KLA.

Fedja had turned back to the fields around us and was looking through the night scope, when he began to hurriedly refocus. He thought he had seen movement. The moment he told the policemen, they asked if they could borrow the night scope to take a look. Strictly speaking we were not supposed to aid combatants in a conflict, but whoever wrote the journalists’ ethical code for conflict zones had never been in a bunker at night, with a hostile unit approaching whose members were not about to say, ‘There’s some journalists up there, so let’s call the mission off and attack tomorrow night.’ They were going to simply blast away at anything they saw. Of course the absurdity of the situation was that we had gone out looking for trouble, and when it looked like arriving, we wanted it to go away. Well, I did anyway.

The police took the night sight and located the unit. The man looking through the lens muttered something to a colleague; his response was to cross himself and take up a firing position behind the sandbags. There were a few tense minutes as we sat in silence, and the policeman watched the KLA. They were a good 200 yards away and he had difficulty making them out, but he could see that they weren’t getting any closer.

Eventually, he told Fedja they were heading in another direction. We sort of relaxed, and about thirty minutes later heard a couple of rifle shots from at least a mile away – something else was on the receiving end.

After another twenty minutes we cracked open a few beers and began to talk. The policemen first demanded to know if I knew Serbian history.

There is no correct answer to this question. If you say yes, you risk being asked a series of questions in which the years 1389, 1878, 1914, 1941 and 1946 will come up. Unless you know the answers you are found to have been firstly lying, and secondly guilty of not knowing the basics of the glorious sweep that is Serbian history.

If, on the other hand, you answer, ‘No, I don’t know Serbian history’, you will firstly be found guilty of not knowing the glorious sweep that is Serbian history, and secondly subjected to a lengthy lecture which will include the dates 1389, 1878, 1914, 1941 and 1946. It will also include several arcane facts that not even Cambridge dons with PhDs in Slavonic Studies know. Serbs are so fascinated by their history that if you ask them ‘What time is it?’, you risk getting the answer: ‘Well, in 1389, it was the time of the great battle against the Turks at Kosovo Polje which resulted in our defeat and subjugation by them for the next five hundred years until finally in 1878 we got our revenge and again became a sovereign nation. A nation able to fight like lions in the First World War against the Germans, a war in which our country suffered greater proportional losses than any other. Alas in 1941 it was the time in which the Germans got their revenge by occupying us. But we fought them again, plucky little Serb nation that we are, even though the Croatians joined the Nazis and killed 700,000 of us in the Jasenovac concentration camp. But they lost in 1945 and so a year later, as the Yugoslavs, it was time to crush the Kosovar Albanian uprising. And now it’s ten past three.’

I had learned that the response to the question about knowing history was to mumble something placatory such as ‘I know you have suffered many times in the past.’ That this failed to address the current situation, in which some Serb units were committing terrible atrocities against civilians, did not make it factually wrong. It usually had the effect of satisfying them enough to talk to me as an equal, as opposed to poking me in the chest. Potentially it meant we could have a conversation in which mention of atrocities by both sides could be discussed.

First though, they talked about the deal about to be signed by President Milošević. Richard Holbrooke had walked into his office in Belgrade accompanied by US air force Lieutenant General Michael Short.

Milošević had stuck his chin out. ‘So, you are the one who will bomb us.’

General Short gave him a right hook: ‘I have my U-2 spy planes in one hand and B-52 bombers in the other. It’s up to you which one I use.’

The police hated the deal. Not so much because it was imposed by the threat of NATO bombing, more because the KLA weren’t required to be a party to it and, as we had just seen, there was no ceasefire. Under the terms, 4,000 Special Police (PJP) were on the way back to Serbia proper, taking their weapons with them. This left the ordinary police and the few special units remaining overstretched and outgunned.

Every time they pulled out of a Kosovar village, the KLA moved forward, took it over and began patrolling the roads around it. They quickly controlled large areas of the province. The Serbs were furious as they’d been winning the war, albeit with brutality, and had crushed a KLA offensive.

These young Serbs were trapped. Trapped in their bunker, in their uniforms, in their nationality and in their history. Nothing could convince them that even if the Shiptars hated them, and even if the KLA were killing their civilians, it didn’t justify what the Serb forces had been doing that summer. If I pointed out that, perhaps, the Serbs had been oppressing the Kosovars since 1989, it was denied. The police would then say ‘anyway, before then they had been oppressing us’ as if that made driving 200,000 people into camps in the hills an acceptable method of anti-guerilla warfare.

We agreed to disagree. I didn’t know if they, personally, had taken part in any of the outrages that had dominated the front pages and TV screens of Europe that summer. Therefore I had no reason to dislike them. They were just young guys who’d rather have been somewhere else. Maybe one of them had taken a fourteen-year-old boy from his mother, bound his hands with barbed wire and shot him in the back of the head as his mother screamed for mercy. Things like that happened. But what do people who do that look like when you take away the dark theatre of uniforms, guns and a scorched-earth operation and they go back to real life? I have met the hardcore, drug-filled, evil, crazy paramilitaries who do some of that stuff, and they are almost reassuringly nasty. Their bandannas, Rambo sunglasses, three-day growths and bandoliers entirely fit the identikit picture. When they got back home they looked pretty much the same, even in trainers, jeans and leather jackets. But we knew that among ordinary units and among the disciplined PJP Specials there were elements who hadn’t so much been ‘behaving badly’ (as one Serb politician squirmingly described it to me) as behaving on an individual basis like a Sonderkommando in Hitler’s murderous Einsatzgruppen in Russia.

These same guys can then have a beer with you, talk football and seem entirely reasonable people. I took the position in Croatia, Bosnia and Serbia that unless I had reason to believe otherwise, the person I was talking to hadn’t committed any crime more heinous than double parking. Otherwise you fell into the trap of demonizing all of them.

As midnight approached our conversation somehow got on to the more pressing situation of my back. It was pressing in the sense that, as I later learned, one of my discs was poking through some torn tissue and rubbing against my spinal nerve. Everyone in the world has a bad-back story and the policemen were no different. Like the rest of us, each of them had either had a bad back themselves, or knew hair-raising stories about how their dad had lived for the last fifteen years with severe lower back pain. We exchanged recipes for bad backs. The TV people offered carrying tripods, battery belts and flak jackets as a sure-fire way of getting a hernia. The police guaranteed a bad back from sitting in old Yugo cars for years on end, and then bouncing round terrible roads. Then various cures were offered. These ranged from ‘miracle wonder back specialist doctors in Niš whom I should really drop in and see should I ever happen to be in the city’, to strange ‘healing hands, channelers of energy’ in Belgrade.

The Serbs were surprisingly prone to vague beliefs about the paranormal. Forty years of aggressively atheist but softish Communism had failed to eradicate what is true of most cultures, an abiding interest in the unprovable. A glance at any newsagents in Serbia revealed a wide range of magazines devoted to astrology, faith healing and lurid stories of the occult.

During the 1990s the regime’s television channel, Radio Television of Serbia (RTS), took advantage of this tendency by devoting hours of programming to Mystic Megović type characters. Their role was to read the future and assure Serbs that it was bright, that the country was going in the right direction. It was obviously a political decision by people who had worked out all the levers of power, and how to use them. One guy, Ljubiša Trgovčević, would come on, and viewers would call in. He would gaze at the studio lights then, turning a ring on his finger, would say, ‘Yes, I see now, I see.’ This was prime-time TV and was taken seriously. In Britain about eight people took Mystic Meg seriously, the rest knew she only got the five-minute slot on the Lottery Show as a bit of light entertainment before the numbers were drawn. Her Serbian equivalents appeared to be working to a prearranged script designed to persuade the population that everything was rosy in the Serbian garden. This was at a time when wars were raging around the borders, inflation was rampant, unemployment rising, pensions were not being paid and gangsters were becoming celebrities. ‘Ah I see now,’ said whichever charlatan was on at the time, ‘Yes, I see that dark forces are against us, but we will triumph.’ Other charlatans would come on to tell Serbs that they were ‘The Heavenly People’.

Then another would come on to read the news. This was usually as far from the truth as what had come before. More strange people would be introduced, including the Wicked Witch of the East who would repeat the message that the country’s leaders were doing the right thing, and that Serbia would triumph over its enemies. She was called Mira Marković and was President Milošević’s wife.

Despite being the leader of the hard-line communist political party Yugoslav Left, Mira Marković looked weirder than all the Mystic Megović characters put together. She had a 1960s bouffant dyed blacker than black from which a variety of foliage would bloom. Her high-pitched voice resembled that of a Balkan Minnie Mouse, and she made the most extraordinary pronouncements about life – both in a weekly magazine column and in her book Night and Day: A Diary. A diary entry describing her social calendar is typically underwhelming: ‘Today, lunching with friends I asked if they happened to have a cigarette. They had a pack of Winston and a lighter, which I received as a present.’

Another column ended with Mira about to go on holiday: ‘I shall have to ask my editor at Duga to release me from my obligations to the magazine. If they agree then I would like to take my vacation.’

What she failed to add was that if they didn’t agree then they probably wouldn’t be editors for much longer.

The police we were with didn’t care much for Serbia’s First Lady but were more sympathetic to Slobo, despite criticizing him for allowing their hands to be tied behind their backs. I suggested this might be a bad analogy seeing as the threat to bomb Serbia was partially due to the fact that too many Kosovar hands had been tied behind backs with barbed wire that year.

It was a good time to go. We had got on fine but I realized I’d crossed a line with this last remark. I was talking to men who had seen their colleagues shot. They may not have carried out atrocities, but they weren’t happy about an outsider criticizing Serb forces. We decided we had enough for our story and exchanged an amicable farewell.

We bid them a safe night, bundled into the armoured car and set off back to Priština and the Grand Hotel.

Ah, the Grand. Brown rooms, brown tap water, lumpy beds, terrible food, suspicious staff and tracksuited gangsters in the lobby. All that for just fifty dollars a night. Still, it was better than what we were leaving behind and much better than the conditions in the makeshift camps in the hills where many Kosovar Albanians had taken refuge.

That was to be our destination the following night.

CHAPTER 2

‘When a man is abandoned by the sun of his homeland,Who will illuminate the path of his return?’

Ghisari Chelebi Khan (Turkish warrior)

IN THE DARKNESS A TINY HAND REACHED OUT AND clutched mine. The hand, which was warm despite the cold outside the tent, squeezed and held on, as if letting go would plunge its owner back into the maelstrom.