Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Books on Demand

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

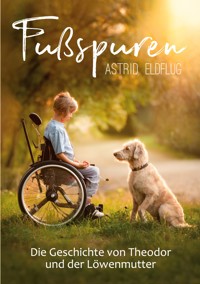

'Until, perhaps, one day we realise what we first thought was a disaster, the worst thing that could happen, is actually a huge opportunity. And that the apparent tragedy has transformed into a miracle.' It comes as a shock when a young mother is informed her son has been born with a rare genetic disorder. According to the doctors, Theodor will never learn to walk or talk. But his mother refuses to accept this cruel diagnosis. Together the pair achieve the seemingly impossible. At the age of five, Theodor stands on his own two feet for the very first time. In an engaging mix of raw emotion and clear objectivity, Astrid Eldflug relates the moving experiences of everyday life with her special needs son. STEPS is a book about unconditional love, empowerment and potential. It is a deeply affecting memoir written with unsparing honesty; a book destined to leave its mark on everyone who reads it.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 544

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Contents

Child’s Play

The Desired Child

The Promise

A Shock

Welcome

A Completely Normal Baby

Certitude

The Lioness

Christmas

Bathtime Fun

The Sixth Sense

A Long Road

Nothing Short of a Miracle

Help?!

A Golden Child

Special Children Need Special Parents

Superdog

Child’s Play

What’s the boy doing?’ The girl is a head smaller than Theodor and throws a questioning glance to her older friend, who’s riding alongside her on a scooter. The pair have been circling around us for several minutes, getting closer with each turn. They eye Theodor with curiosity and grin shyly at me. I smile back at them.

‘He can’t do it yet,’ says the taller of the two, as though that explains everything. It all makes sense to them.

My heart leaps with joy.

‘Exactly,’ I say, because they both understand.

‘He’s just learning,’ I explain with pride.

They nod and scoot off. I can’t see whether Theodor is smiling, since I’m standing behind him, body against body, and guiding him with my movements to another step. My arms are laced under his armpits and, with a special grip, I hold his small hands so I can help him shift his weight from one leg to the other. I gaze down at his feet, focussing all my concentration on the impressions that I’m getting through our physical contact. When will he be ready to take the next step?

His white leather shoes, with the dark blue stripes on the side, look like normal trainers. But they cost more than two hundred euros and, around his ankles, two narrow metal bars can be seen peeking out from under his trouser legs. The custom-made lower leg braces, hidden beneath Theodor’s jeans, weren’t much cheaper than a small second-hand car. With every step, the metal joints of the leg braces glint in the sunlight. We are in Danube Park and enjoying the first warm spring day of the year. The sun is shining and I’m beaming with happiness because Theodor is in the process of walking in a park for the first time in his life. He is six years old.

What comes naturally to children of his age is an absolute miracle for Theodor. He doesn’t develop in the same way as other children. Theodor was born with a rare genetic deletion. He’s missing an important piece of chromosome 5, which is essential for development. 6.5 megabase pairs have been lost in his genetic material, including an important gene known as MEF2C. While, at first glance, this seems like a meaningless combination of four letters and a number, this particular missing gene has changed my entire life. Although the missing piece in the genetic material is so minute that it would be imperceptible to the naked eye, the absence of this one crucial gene has a dramatic impact on development. The genetic deletion is called 5q14.3 microdeletion syndrome and has recently also been named MEF2C haploinsufficiency syndrome.

What sounds like a mathematical code has far-reaching consequences for my son’s development. How would I explain this diagnosis to the two girls?

We’ve often heard children in the street asking their mothers, ‘What does that boy have?’ (That’s if they realise, despite his blond curls, that Theodor isn’t a girl.)

What does my son have? Or, more accurately, what doesn’t he have? Indeed, if the complete MEF2C gene were present on both chromosomes, Theodor would probably be playing football, riding a bike, going to school and learning to read and write like most other children of this age. But Theodor is only just learning to walk. And this is a true miracle for him.

Once, in the playground, I tried to explain to two primary school children that Theodor can’t yet sit on the swing by himself because he has a genetic disorder. By the look on their faces, I could tell they had no idea what I was talking about.

‘Is he sick?’ asked one of the children.

A genetic disorder is not a sickness. But children don’t normally know what a genetic disorder is.

All information about us humans is stored in our genetic material, in a manner not dissimilar to that of a big library. The library is known as the genome, the entirety of our genes. Our hair colour, our eye colour, whether we are tall or small – all of this is written down in 46 books in our body’s very own library: the chromosomes. What’s so special about it is that each book exists in duplicate. 23 chromosomes are inherited from the mother, the other 23 are from the father. In this way, the body protects itself in the event of a typing error in one of the books. Now, you can image that the sentences in these books are made up of many, many words: the genes. Each of these genes represents a certain word; it is, so to speak, the code with which the body can produce a specific protein.

Theodor is therefore missing several words in this enormous library. They were lost long before his birth. Despite having an intact copy of the MEF2C gene on one of the pair of chromosome 5, this single copy is not enough to produce sufficient protein. Some children are only missing a single letter in one of these words. Other children may be missing several letters, or even the entire word. You can think of it like this: if a single letter is missing from a word, the newly created word may no longer make sense. Or it makes a completely different sense than what was originally intended. In the case of a particularly important word, an error might also result in the entire sentence no longer making sense.

If you see the letters har written in a book, for example, you may wonder whether it is an original word that you have not previously come across or whether perhaps an error has been made in writing it, and that it is actually meant to be hare, hair or hairdressing scissors. Perhaps only one letter has got lost, or perhaps several. Depending upon how many letters are missing, the word may no longer make sense. But if the entire word is missing, it may be that the meaning of the sentence as a whole is lost. In Theodor’s case the entire MEF2C gene is missing, which is why he develops differently to other children.

I rarely talk about Theodor being disabled, even though his disability pass shows a disability rating of 100%. But what does such a classification mean? And what other terms can I use to describe Theodor’s development? Some parents say their child has hurdles to overcome. Maybe the child has only one hurdle, or maybe they have many. In any case, it sounds like a lot of work. But it also sounds as though something is broken in this child and needs to be fixed; that something is wrong with this child and needs changing. I would rather use a term that is more respectful.

I also rarely talk about my son having special needs. He has exactly the same needs as any other child his age. He wants to be loved and acknowledged, he wants to play, have fun and to discover the world. Sometimes I say that he is a unique child. Because there is probably no other person in the whole world who has exactly the same genetic disorder. But isn’t every child unique in his or her own way?

My favourite thing to say is that he is a very special child. For me, he is the most wonderful child in the whole world.

Other children are usually fascinated by him. When Theodor walks along Franklinstraße with his walker, the gait trainer, he attracts everyone’s attention. In September, when we took the walker for a spin among the tourists at Lake Tegernsee, you could say that we were a bit of a sensation. Many people stopped and smiled at us. They were amazed at how well Theodor can move in his walker and how fast he can go.

Many people have never seen a gait trainer before in their lives. How often have we heard the question: What’s that?

I usually explain to children that a walker is something like having their own balance bike – a balance bike on four wheels. When the children are older, I ask them if they can still remember the time when they, themselves, were on the road with a baby walker or a balance bike. Most of them immediately understand what I mean. When I tell them that Theodor can’t walk yet, some children feel the need to show me their own skills. They start running, jumping or prancing around next to us.

‘Look at me! I’m already walking!’

How should I react in such a moment? Of course, I tell the child how great they are doing. But I would be lying if I said I wasn’t also suffering at the same time. I would be lying if I said that it doesn’t sometimes hurt me to see how different these children are. How easy everything is for them. They can walk and talk. And they didn’t even have to work very hard to learn these skills. It happened automatically. They grew, got older and just learned. Easy-peasy. Child’s play.

These things aren’t so easy for Theodor. Some days I’m aware the sadness cannot simply be shrugged off. Other days it doesn’t bother me at all. In my eyes, Theodor is a very normal child. I never compare. It’s only when I compare that it becomes clear just how different he really is. It’s only by comparing him to other children that you notice what he would normally do at his age.

By not comparing and instead accepting the child as the unique human being they are, you begin to view them differently. You see the child’s abilities and where they stand in terms of development. It’s difficult for me to imagine Theodor as one of those other children. Only rarely do I envisage what he would like to do if he didn’t have a genetic disorder. What would his interests be? Would he be a quiet or a lively child? Would he climb trees in the forest or play the piano? All these things seemed so important to me before Theodor was born. Today, I have other priorities in my life.

What would it be like if Theodor were more independent? Would he leave the house every morning with his satchel on his back and wave to me once more from the street? Would he make me a little present on Mother’s Day, recite a poem and then give me a moist kiss on the cheek with his little child’s mouth? I have tears in my eyes when I think about it.

When Theodor was born my mother gave me a small booklet with drawings and sayings. Each page shows a mother kangaroo and her baby or joey. One of these drawings particularly touched me. With a mischievous smile on its face, the little joey is sticking its head out of the mother kangaroo’s pouch. The mother looks lovingly at her joey and strokes its head. “I’m always just right for you...” is the caption to the picture. The kangaroo mother presses a rubber stamp on her belly so that the caption reads, “Contents: 100% perfect.”

When my mother gave me this book in the hospital during the difficult post-birth period, and I discovered this page while leafing through, I glanced at my baby lying in my arms and gazing at me with his grey eyes. Theodor had the wisest look I had ever seen and he looked directly at me. Out of his nose hung a thin green tube, the feeding tube, and attached to his hands and feet were other tubes and IVs. I didn’t know what to expect or what lay ahead of us. The time that lay behind us had been more than difficult. I didn’t know if the doctors were right in their fears and I didn’t know what was wrong with my son. In my eyes, Theodor was just right. He was 100% perfect.

With the benefit of hindsight, the image of the rubber stamp makes me reflect. As far as the kangaroo mother is concerned, her joey is perfect. But how is the baby stamped by others? What expectations do others have, and what ideas and images do they associate with a baby, when it is clear in advance that he or she is different and has neurological abnormalities?

The doctors had already labelled Theodor as disabled before he was even born. They had very low expectations for his development and there was also very little room for joy and hope. I vividly remember the moment when I entered the delivery room and heard the doctors whispering in the room next door. The protocol already stated that my son was disabled, although this was only an assumption until the genetic examination a few months later. This assumption was based on conjecture, yet it influenced the entire birth process and the medical events immediately after the birth. Theodor was never given the opportunity to enter the world without prejudice. He was stamped as disabled from the outset. And this also determined the constraints that would go along with any disability.

On the one hand, this early diagnosis naturally had advantages, since we could do everything feasible to minimise risk during the birth. We were also able to start physiotherapy just a few days after the birth. On the other hand, this assumption brought many disadvantages in addition to the trauma of the experience. For one thing, the doctors didn’t even want to give me the opportunity to hope for a natural birth. I had to fight with all my energy to prevent a caesarean section from being performed immediately. Only with the utmost willpower was I able to ensure that Theodor could choose his own date of birth.

The doctors’ assumptions and fears had made me so anxious that I was prepared to not see my perfect baby pop out of my belly, but rather I expected a terrifying, monster-like creature. The doctors had actually managed to rob me of all joyful anticipation of my baby, and I welcomed my son knowing that there was something fundamentally wrong with him, even though no one could tell me exactly what it was.

During the first moments after his birth, I never had the opportunity to understand my baby as the miracle he was. I never had the chance to get to know my son without expectations and to simply marvel at him. Someone had already put a black stamp on him in my belly, just like the kangaroo mother did with her joey. The only difference being that the inscription on my belly did not point to a perfect baby, but rather branded my son as disabled in advance.

Children approach Theodor very freely because they are yet to have this preconceived idea of what is normal, and this makes some adults look down in shame when they see us. I was often hurt by these reactions in the past, but now there are also days when I get angry about them. The nicest thing I heard was a mother answering her child’s question, ‘Mum, what’s the boy doing?’ with a simple, ‘He’s going for a walk, just like you!’

Some parents, however, drag their children along by the hands when they start staring at Theodor or asking unpleasant questions. Children have a talent for badgering you with their questions until they either get a satisfactory answer or they can’t think of anything else to ask.

A dear friend of mine also had her reservations when, after a long absence, she wanted to visit us accompanied by her two children. She warned me in advance of the possibly embarrassing questions from her eldest, who is the same age as Theodor and had already seen him on several occasions. She warned me to be prepared for unpleasant questions because the two children had never had anything to do with disabled people. Her words hit me in the pit of my stomach. Recovering, I took a deep breath and answered, ‘So they’ll have the opportunity to learn something. Genetics for beginners.’

In the end, the children did not pose a single question during the entire visit. They accepted Theodor exactly as he is and viewed his behaviour as something completely normal, regardless of whether it was different from their own behaviour or not.

When Theodor sits in his buggy, most people don’t realise that he is special. He’s just a child like any other who is taken for a walk. When we are out and about with the buggy, most toddlers just point at him and proudly say, ‘Baby!’ and their parents praise them for it. Most of these children are much younger than Theodor.

At eight years old, is Theodor still considered a baby despite being twice as big as the tiny tots who scurry past him on wobbly legs? In a way, my son is a baby. He drinks from a bottle, has to be fed and wears nappies. He likes to suck his fingers, has a passionate enthusiasm for baby toys and loves to rock in a baby swing. He can’t sit, crawl or walk on his own. And he’s never said ‘Mummy’ in his life. But, as the two girls in the Danube Park said, ‘He can’t do it yet’.

Theodor has learned so many things that were unimaginable years ago. He has learned to reach for toys, even though his hands were so contorted when he was born that he couldn’t open his fists for three years. He has learned to hold his head upright, even though his shoulders were so cramped a few years ago that his neck was actually invisible. He has learned to turn on his side, even though he hardly moved at all for years. He can eat and drink, despite the doctors immediately attaching a nasogastric tube to him after his birth.

He can play in a sitting and kneeling position and is interested in games and picture books. He loves music and recognises his favourite songs. He can play my old keyboard by himself. He can stand up with my support, and he took his very first steps a year ago. All these things seem so obvious when we see them in other children his age. But Theodor has fought hard for every single step forward. And I have helped him along the way.

A few months later we make another pleasant acquaintance on the street in front of our house. We live opposite a school on a quiet side street near the Old Danube, a former river branch of the Danube. Theodor can now take really good steps and, with my help, every evening walks two hundred metres past our house, down the street to the crossroads, then across the street, past the school and back to our starting point.

On one of these evenings in summer, when we can stay outside until 8:00 p.m. (after that the street lights switch on and Theodor’s attention is drawn to the bright lights like a moth to a flame), two children come running towards us from behind. To begin with I am merely aware of their footsteps coming closer, since my gaze is directed downwards at Theodor’s feet. Only out of the corner of my eye do I see that they are not walking past us, but are obviously watching us walk. I glance up. The girl has brown, curly hair and is about the same height as Theodor. The boy is also the same age. We know him by sight, since he lives in one of the neighbouring houses.

A few weeks earlier, I explained to him why Theodor has to wear lower leg braces when he walks. ‘If someone doesn’t see well, they get glasses. These help them to see. Theodor can’t walk on his own yet. The braces help him so that his legs are more stable.’

The two children start to argue about who gets to walk next to us. To begin with I wonder if they are making fun of us. But their interest seems genuine. Finally, the girl walks on our right and the boy on our left.

I am actually completely focused on Theodor, since I need to have full control over his weight and movements with every step. One moment of distraction and he would slip from my hands. One stumble and he would fall to the ground without braking. He doesn’t yet understand that it is dangerous to fall down. Above all, he doesn’t yet have the necessary body control to prevent or break a fall. He is completely dependent on my support. Nevertheless, I try to give the children some of my attention.

‘He can already walk very well,’ says the boy, impressed.

I am very happy about the compliment. When an eight-year-old child can see how much Theodor’s walking has improved, the progress must be really obvious. The girl has many questions. ‘How old is he? What is his name?’

Theodor is now seven years old.

‘The same age as me,’ says the girl. Her name is Elsa. The boy’s name is Leon. He is already eight.

‘Why doesn’t Theodor go to school?’ Elsa asks.

I explain to her that Theodor has to learn many things that are not taught at school. He can’t sit yet and he can’t walk unaided.

‘But he’s learning now, isn’t he?’ Elsa exclaims enthusiastically. Her joy is sincere.

‘And you’re teaching him, aren’t you?’

While we walk down the street and I simultaneously try to concentrate on Theodor’s steps and the children’s many questions, I tell them about Theodor.

‘Can he speak?’ the pair ask.

‘He can talk in his own language, but he can’t say any proper words yet.’

‘Like a baby? So, like this – ah, mah, ma?’

She’s understood.

‘Look, he’s wearing braces! They help him walk.’ Leon points to Theodor’s feet and is proud that he can explain something to Elsa.

‘And you always practise together?’ she asks me.

‘Yes,’ I say. ‘Theodor can do so many things. But he can’t do them on his own yet. That’s why I help him.’

Elsa tells me that her parents have decided to get a family dog. They’re going to pick him up tomorrow.

‘I’m going to name him FOREST,’ she tells me, spelling out the name, ‘…after Forest Gump. That’s my favourite movie.’

I’m surprised that she even knows the film at her age.

‘He also had to wear leg braces, didn’t he?’ I ask her.

‘Yes, but then he just ran, the braces broke when he ran and then he could walk without braces,’ she explains to me.

‘Like Theodor?’ She looks at me hopefully.

‘He’s so cute!’ she says, beaming at Theodor. ‘He’s just smiled at me.’

I received the diagnosis shortly after he was born. My wonderful baby had a rare genetic deletion that causes severe developmental delay. The doctors handed me a note that described my perfect son in these terms: “severe mental retardation, lack of speech and stereotypical movements”. They said he would never learn to walk and talk, and sent me home. At that moment, my life as I had known it collapsed. All my wishes, dreams and hopes were dashed. A journalist once asked me where I get the strength for our daily life.

‘I didn’t choose for Theodor to have a genetic disorder,’ I replied. ‘Nobody ever wishes for that. But that’s the way it is, and we try to make the best of it.’

Nobody ever wishes for that. And yet there are people who think a disability is something that fits into one family, but not into another. When a dear acquaintance had just become pregnant with her twins, she told me over breakfast that, of course, they had done all the tests. A disabled child would not be fair to her first-born son.

‘Besides, it wouldn’t fit into our family. We like to travel.’

Theodor and I also like to travel. He loves the sea, and we have already travelled as far as Denmark by car. I know some parents who travel all over the world for their children’s therapies. Dolphin therapy in Egypt or Bulgaria, stem cell therapy in Panama or Mexico, treatments in Germany, Denmark or California, hip surgery in New York. But these are probably not the kind of trips my acquaintance is dreaming of. But who dreams of therapies when they want a child?

I think it is rather naïve to believe you have the power to choose between a perfect child and a disabled child. Even if you had the choice, what would you choose? Some people speak of the quirk of nature, others of fate, some even call it destiny. Was it nature’s experiment or a stroke of fate? No matter what you call it, I can confirm – from my own experience – that you do not have this choice.

Some things are beyond our control. We have no influence over them. We can try as hard as we want to do what is best for the baby in our womb. We cannot prevent things sometimes happening that we don’t expect. Things that, at first, make our world come crashing down. Things that go way beyond our greatest fears. Things that appear so unexpectedly that we aren’t prepared for them, since we can’t think that far ahead. We have no influence over these things. We can only learn to deal with them. Until, perhaps, one day we realise what we first thought was a disaster, the worst thing that could happen, is actually a huge opportunity. And that the apparent tragedy has transformed into a miracle. I think it is more than unfair to not even give a disabled child the opportunity to be perfect. Are perfect and disabled really opposites?

‘He is my easiest child,’ I once heard a mother say, with a twinkle in her eye, about her child with this rare genetic disorder. And yet she has four children.

Theodor is a wonderful child, although our life may not even remotely resemble that of an average family with an eight-year-old. Yet he was exactly the baby I had been looking forward to for nine months. He, and only he, was the baby I had desired. And he is the son who means everything to me.

Having a perfect child always means accepting the child as they are. Only then do you really see the child. And if you manage to see the child as the individual that he or she is, then this child becomes a perfect child, without having to fit into a certain mould.

I had no mould for Theodor. There was no mould in my head that he had to fit into. The diagnosis was still a huge shock that changed my entire life. Although I hadn’t had any concrete ideas about what I wanted from my life with a child, the reality as it finally presented itself was exactly the opposite of any idea I could have had. After all, at the age of 27, I had no experience whatsoever with special needs children. I knew nothing about physiotherapy, orthotics or leg braces, or of the medical interventions that the children of some of my friends and acquaintances had to undergo. The operations that would have to be performed, or had already been carried out, had names I’d never heard before in my life.

I knew about the biological basis of DNA because I had attended the bioengineering course of a part-time technical college after completing my university studies, but I was not prepared for the real-life implications of those subjects we’d had to learn on paper for exams. Instead of buying a football or balance bike for my son, I buy adaptive tricycles, walkers and standing frames.

I’ve heard many parents say, ‘I wish my child had been born with an instruction manual.’

Each child with this rare genetic disorder is so unique that there are no guidelines for their development. So, what should you expect when you receive the devastating diagnosis? Should you believe the doctors’ prognoses and give up all hope? Should you try to hope for the best? Or should you just let yourself be surprised? Many things would be easier in the first few years if you’d been given a user’s manual at birth, with instructions on how to optimally promote your child’s development, despite the genetic disorder.

Theodor made hardly any progress during the first years of his life. The idea that he would ever take steps seemed absurd at the time. He could not even control his head. His hands were clenched into fists, he made no eye contact, he couldn’t roll to the side and, of course, he couldn’t sit up. It was depressing. I then changed my own mindset. Instead of focusing on his obvious limitations, I started looking for his abilities. I started looking for opportunities. It seemed as though there was absolutely nothing he could do. But was it really so? Was there anything he was capable of achieving?

When a child is confronted with special challenges, they need a special mother. So, I became that special mother for my son. I became an inventor, a genius at observing his potential, and I focused on what he could do. Gradually I realised that there were actually a lot of things he could do, I just had to find them and help him find a way to improve them. As I began to notice small changes, I recognised each of these small advances as one of many thousands of tiny milestones. I began to rejoice in each of these small improvements.

I thought, ‘If he could learn this, maybe he can learn something else, and something else, and something else.’

In the beginning, the changes may have seemed tiny. At first glance, they may have seemed insignificant. But when many small changes are layered on top of each other, they can become big changes. Theodor has learned so many things, even though many people didn’t think it was possible. The prognosis you get with the diagnosis of a genetic disorder may be right. But it may just as well be wrong. No one can know in advance how a person will develop. When Theodor was born, many people did not believe in his potential. But I never gave up hope. I always felt that Theodor actually wanted to reach for toys, but that he couldn’t. I always felt that he wanted to sit up, but that he couldn’t. I knew I had to find a way for him to learn.

His developmental journey is unique. It is a long and arduous journey because my son has to work a thousand times harder to make progress than is the case for a child without a genetic disorder. Along the way, we have already experienced many stories. Some of them were funny, others sad. Some of these stories have been the stuff of movies and not unlike tragedies. It was at this point that I decided to write a book about our story. This is our shared story. It is a book filled with hope, love and inspiration.

The Desired Child

The sun shines brightly in the sky. Theodor is wearing blue shorts decorated with yellow sharks. I have concealed his wet nappy in my beach bag. The sound of the wind carrying the salty sea air to our beach spot mingles with the buzz of voices from other bathers to form a soothing murmur. Theodor lies under the parasol in the shade and tolerates my hands relentlessly smearing him with sticky white sun cream. Only when I try to apply the cream to his face does he turn away from me and try to escape my hands. Finally, we make it. I then put his blue sunglasses on him and ensure the side-arms are tucked well behind his ears. Theodor thrashes his legs and pushes the bath towel aside. His feet land in the warm, soft sand. With every movement he stirs up a small cloud of dust until not only is the towel covered with a thin layer of sand, but countless grains also stick to his freshly creamed legs. Now we’ll definitely have to go into the water to rinse off the layer of sand again, before he reaches in with his hands and perhaps smears it all over his face.

‘Come on, Theodor,’ I say and stow the sun cream in the beach bag.

My parents are still in the holiday apartment, and Veronika has gone to the beach kiosk to buy cappuccinos for us. I roll Theodor to the side and, with a practised grip, push my arm between his legs so that the back of his knee comes to rest on my lower arm. I then roll him over the side to a sitting position, grabbing his upper arm with my hand so that I can hold him securely. With a deft movement, I push myself up with my knees and stand upright with Theodor in my arms. It reminds me a bit of an exercise in the fitness centre, where I lift a heavy weight effortlessly from the floor.

The ease with which I lift my son is deceptive. You could almost think I’m carrying a baby in my arms. At first you might not suspect that Theodor is 1.15 m tall and weighs 25 kg, since I’m only carrying him with one arm. How frequently have I lifted him up and put him down today? I make a mental calculation: I have already completed this exercise 36 times today. The slight backache confirms this to be a pretty impressive number. Having a special needs child can also be very physically demanding. Some days it is even hard work. Anyone who has ever done squats with 25 kg on their arms, or pushed a 50 kg buggy through sand or snow, knows what I’m talking about. This is CrossFit® at its most extreme.

I’m a bit more careful than usual when carrying Theodor, because the sun cream makes him feel slippery.

‘We’re going down to the water,’ I tell him.

We’ll get the swimming ring later. For now, we’re going to play in the sand in the shallow water. Theodor rubs his hand over his face and also catches the sunglasses. The lenses I had cleaned earlier are now smeared with sun cream. Oh well... I sit down on the sun lounger with my son in my arms and try to clean the glasses as best I can, so that he doesn’t merely see the smeared areas on the darkened lenses.

We are now ready to set off. The sand is so hot that I would normally run the short distance to the sea. But I can’t do that with Theodor in my arms. Instead, I walk as fast as I can until I finally feel the cool wetness of the waves on the tips of my toes. I envy all those parents whose children run into the water by themselves. At the same time, I’m happy to see Theodor sitting on the sand without any help from me, after I’d put him down a few metres away from the water’s edge. Every few minutes, a particularly high wave manages to roll up to our feet. Theodor pulls his toes back. The water is still too cold for him today. Although the sun burns from a cloudless sky, there is a cool breeze that makes the heat bearable and even gives me goose bumps on my arms from time to time.

Theodor digs his toes into the wet sand, which is dark brown here because it is so waterlogged. Using his hands, he begins to burrow into the sand. I sit closely behind him, ready to catch him immediately if he tips forward or to the side, or if he throws himself backwards in a fit of exuberance. It’s the first year that Theodor is stable enough to sit in the sand without my support. The sound of the sea and the wind exert a strange fascination on him, which in turn has a magical effect on his muscle tone. At this moment, he feels like a different child. Normally he is a bit wobbly, and his upper body feels very soft – like jelly or a piece of rubber. Here, at the sea shore, his muscle tone is so good that he sits with his back completely straight.

Whilst I take care we don’t get splashed by the other children, who are running boisterously all around us, I also ensure that Theodor doesn’t unexpectedly shovel a handful of sand into his mouth. It’s amazing how energetic he is here at the water’s edge. An idea occurs to me. I want to test whether he might even be able to stand in the shallow part. It’s low tide and the sea has receded so far that the shoreline merges into it via a long, shallow sandbank. The sandbank is dotted with small pools of water in which children build their sandcastles. The sea is only ankle-deep for the first two metres. Unlike some other days, the water is crystal clear today, and the sunlight sparkles on the small waves. The current in the shallow water has left a wavy pattern in the sand.

I lift Theodor up and carry him a few metres towards the sea. Now I feel the wavy sand beneath my toes. Slowly I let his feet slide down. He initially pulls his legs up when he feels the water but, after a while, he gets used to the temperature. For the first time this year, the soles of his feet touch the sand. I feel him bear the weight on his feet, and I let the grip of my hands become looser and looser until I’m merely steadying him very lightly under his armpits. It is impressive.

The sun makes Theodor’s sandy-coloured hair glow golden. His hair has formed into little curls due to the salt water and the ocean breeze. A few weeks ago, my son got his first haircut from a proper hairdresser. The hair at the nape of his neck is cut short, at the sides and in front he has a real surfer’s haircut with long, wild strands that are tousled by the wind. Standing up, his head reaches just above my belly button.

I glance at my belly and see the scars left behind from the pregnancy. Childbirth has indeed left its scars – not only on my skin, but also in my heart. Just as my body has changed from that of seven years ago, I too have become a different person. I remember when my nephew said to me, a few years back, that my belly looked like that of “an old granny”. He meant it as a joke. I wasn’t offended by it because my body is proof of what Theodor and I went through at birth.

I can feel how stable Theodor is standing in front of me, and I lean his back against my thighs. For a fraction of a second, I have the impression that he is standing unaided. And that gives me the courage to try something we’ve never done before. I completely remove my hands, which are supporting him at his sides. And Theodor stands by himself, his feet buried in the sand, his back leaning against my thighs. It is incredible. With a glow on my face, I place my hands gently on his shoulders so that I can support him when his knees buckle. I know that this could happen at any moment and that he would simply fall over, completely helpless, if I didn’t hold him.

I look down and see a small shoal of tiny fish swimming past, next to our feet. My son doesn’t notice the fish. He stands leaning against my body as though it were completely natural. Encouraged by what was an overwhelming moment for both of us, I reach under his armpits and take his hands in this special grip we discovered only a few months earlier. The grip helps me to shift his weight from one leg to the other and, at the same time, gives me the opportunity to catch him safely if he stumbles or if a foot doesn’t land well when he takes a step.

Slowly I shift his weight and watch to see if I can feel him lift one leg. It takes a moment because the cool water has not only made Theodor’s body very strong, but also a bit stiff. But then he first lifts one leg out of the ankle-high water, takes a step, and then lifts the other leg. My seven-year-old son is walking in the sand for the very first time. I am aware that every step is a small miracle.

Since he doesn’t wear any lower leg braces to help him bend his feet at a 90-degree angle, Theodor’s toes land on the sand first with every step. He looks a bit like a stork walking in the water. I see a family next to us going out to the open sea in a pedal boat. They wave at us. I am incredibly proud of Theo-dor. And of myself too. And of what we have achieved together. It is a perfect moment. It was here, in Italy, that our story began. It was on this beach in Venice that I first felt the desire to have a child.

A little later, after we’ve walked from the boat rental to the next stretch of beach, I notice that Theodor’s legs have turned a bluish colour and that he has goose bumps. So, it’s time to end our walk for now and to wrap ourselves up in the towels at our beach spot. I look back once more at the small footprints Theodor’s feet have left in the damp sand. Those footprints mean everything to me at this moment, since they are proof that my son is indeed standing on his own two feet. I’ve been waiting for this moment for seven years.

‘Bravo, Theodor,’ I say. After all, we are in Italy and I want to praise him in Italian. I would love to throw him into the air with joy, but he is almost too heavy for that.

I rinse the sand off his feet in the sea and carry him back to our beach spot. Meanwhile, Veronika has returned from the beach cafe with two cappuccinos. She has shaken out our towels and laid them neatly in the shade. We spread several beach towels next to each other, since Theodor needs enough space to roll himself around. After drying him, I change him into a fresh nappy, shorts and a T-shirt. I tickle his tummy and enjoy his laughter, which is also something very special. Theodor rolls from side to side while my fingers tickle his belly. His little mouth is open in a smile and I can see the two gaps between his teeth. In April, the Tooth Fairy took his first baby tooth and, just a few weeks ago, she turned my son into a cute version of Toothless, the little black dragon from the animated film How to Train your Dragon, when she also took his second incisor.

Once Theodor has had enough of the tickling, I reach for the cappuccino. I remember my pregnancy, when I gave up coffee for nine months so as not to put the baby in my belly under stress. I remember all the other things I paid attention to. In the end they couldn’t prevent my baby from being born with a genetic disorder. Even now, seven years later, I still think about it sometimes. The question of Why? is still not forgotten, although it has mostly faded with the passing years. Here, in the sunshine, all is well. Theodor has just walked in the sand for the very first time.

A couple of deckchairs away sits Francesca, our Italian acquaintance, who says “Hello” instead of “Goodbye” and likes to brush up on her German in an animated discussion with me. Her knowledge, however, is limited to a few simple sentences that are no match for a real conversation. That’s why I prefer to talk to her in English.

‘I saw Theodor was walking,’ she calls out to me enthusiastically.

‘Very good!’ She claps her hands and smiles at us.

I am proud that she saw us. Francesca has three children. Two of the children are the same age as my nephew, and the youngest of the family, Giovanni, is four. I watch him play catch exuberantly with the other children. Every year it becomes clearer how big the difference is to Theodor’s development. In the past four years, Giovanni has developed from a baby into an independent little child. While he romps around with the other children, his mother relaxes in a deckchair and reads the newspaper. My son is almost entirely reliant upon me. There are only a few things he can do all by himself and, even then, you have to keep an eye on him to make sure he’s safe. Giovanni, on the other hand, puts on his inflatable armbands unaided, calling out ‘Ciao, Mama’ to his mum as he runs off. The next moment, he and his siblings have disappeared into the sea.

When my parents arrive at the beach, it’s time for Theodor to get something to drink. I’ve brought my own still mineral water in glass bottles from Austria, which I decant into a baby bottle. I think back to the summer holiday, when Theodor was three. On the way to the beach, one of the baby bottles fell out of my mother’s swimming bag and shattered into thousands of shards, damaging the bottle teat in the process. Although our car was packed to the roof with luggage, I hadn’t thought to bring several teats. We now had a real problem. Theodor could drink from a cup, but only very small amounts and only in sips. That would be far too little in the heat and, most importantly, he couldn’t hold the cup by himself. He was used to drinking from a certain teat. As it turned out, this teat was not available in Italy. So, we had to think of something.

My father set out and tried his luck in all the pharmacies within a one-hundred-kilometre radius. When he couldn’t find anything, he had to extend his search area, only returning hours later. In the end, he’d had to drive back to Austria to buy the right teat in the first town just after the Italian border.

My mother lifts Theodor up and sits on the lounger, supporting him on her lap. When she shows him the bottle, he immediately opens his mouth. He is thirsty. While he is busy drinking, I take the opportunity to go swimming. This is impossible when I’m alone on the beach with Theodor. I walk the few metres to the sea and continue through the waves until the water reaches my waist. I then allow myself to fall into the next wave and swim off. The water forms a pleasant contrast to the warmth of the sun shining on my face from above. I turn onto my back and swim even further. The noise and the children’s laughter become increasingly quieter the further I get away from the beach.

It is said that a child chooses their parents. Many people are convinced that a child’s soul searches for the right place and decides if and when to be born. It searches until it has found the right mother and discovered a place in which it will be happy. Only then does it enter the world. Did Theodor find me in this way? Did he choose me and decide that he wanted to live with me?

Shortly after Theodor’s birth, my aunt said to me, ‘Everyone is only expected to bear as much as they can.’ The meaning of her words was no consolation to me at the time. On the contrary. How much suffering can a person bear? Why should some people be able to bear more than others? Above all, I didn’t want to accept that I, of all people, was expected to bear more than other people – just because I can? That didn’t feel fair.

‘Life is not fair,’ someone else said to me. This was particularly hard. It was not comforting, but instead made me feel naïve because I had actually hoped that life would be fair to me and my child. Was I wrong to wish this? Why didn’t we deserve a little happiness too? Because I could bear the unhappiness? In fact, I didn’t feel I could bear more than other people and – above all – I didn’t want to have to bear more.

Today, people refer to me as a “lioness” and my son as a “fighter”. I picture the two of us together. While I am a majestic wildcat, my son is standing next to me wearing tiny little boxing gloves. While I would defend him to the death, he fights his way through life. The lion is one of the world’s most powerful predators. I never saw myself as a powerful woman until Theodor was born.

‘Theodor is so fortunate to have chosen you as his mother!’ Carla Reed, a therapist from the USA whom I respect very much, wrote to me on Mother’s Day.

This sentence brought a smile to my face. I like to think that Theodor feels good with me. That he has seen he belongs to me and has chosen me as his mother – regardless of whether I am a lioness or perhaps just a normal woman with fears, worries and weaknesses.

Theodor is genuinely a desired child. When I imagine that he was buzzing around us looking for a good place and chose me, I think I could sense his decision at the time. He was knocking on my door, so to speak. I was 27 years old and it was the height of summer when I first felt the indescribable desire to have a child. Theodor seemed to be in a hurry. He was meant for me and he had found me. And the overwhelming urge to have a child came to me from one day to the next, even though I hadn’t really given the subject much thought in all those years that had gone before.

_______________________

It all started here in Italy, in the place where so much has already begun. When I was one year old, it is here that I baked my first sand pie. And then, three years later, my cousin and I proudly drove home with a trophy in our hands. We had won the sandcastle competition. Later, I went to a disco for the first time, was kissed for the first time and spent my first holiday with my school friends, without my parents. And, when I was 27, I started to think about why I couldn’t take my eyes off the tiny babies on the beach, why I had tears in my eyes when they came running towards their mothers, and why I got goose bumps when I saw them laughing and crying.

It started when I was walking on the beach in the evening sun, watching the babies and toddlers deftly moving in the sand, performing their acrobatic position changes, standing on wobbly legs until they finally just toppled over and landed on their little nappy-clad bottoms, and then how they were all crawling towards the foaming waves at an unbelievable speed, as though they were racing one another. Some got up, took a few steps, fell to their knees and kept crawling and scrabbling. And I remained fascinated as I watched the little creatures splash around in the water with their hands and arms and, only at the very last second, before a high wave could splash over their little heads, were they scooped up by the rescuing hands of their adult companions. Mums and dads fished their babies out of the waves and carried them back to their starting point. As soon as they got there, everything began all over again. The babies shuffled on their bottoms, switched from sitting sideways to kneeling, got into their starting positions and crawled off. The spectacle reminded me of the little baby turtles that scuttle towards the open sea as soon as they hatch, and are washed out into the ocean by the first wave.

For the first time in my life, I couldn’t take my eyes off the babies. I was certainly not one of those women who, as early as nursery school age, shriek every time they see a baby anywhere within a two-metre radius. I felt ambivalent towards babies and even a little cautious, since I hardly had any experience with them. I didn’t have any relatives who entrusted me to babysit their little ones every weekend. Nor do I have any younger siblings.

Until that day, my experience with babies had been largely limited to playing with a special doll called BABY born®. This doll, which was super-modern in the 1980s and was later to serve me as a training model for putting on nappies and dressing, was primarily distinguished by one special detail: a gooey paste could be mixed from the powder supplied, which could be fed into her mouth using a doll’s bottle. If you then put the baby doll on her potty and waited a few minutes, the potty would magically fill up with yellow liquid.

To be honest, as a child, I was more interested in cars than dolls. When my neighbour and I played prince and princess, it was almost always me who had to be the prince (she was a year older than me and shamelessly took advantage of being allowed to wear my mother’s beautiful pink sequined dress). However, the technology behind the feeding function of the BABY born® interested me and I was keen to find out how it worked.

I also didn’t have any overly pronounced wedding fantasies as a child. At the age of four, for example, I was firmly convinced that I would later on marry my cousin, and it made me really angry when my parents said that wasn’t possible. But one of my favourite Christmas games was to re-enact the story of Mary and Joseph, picking out the beautiful woven shawl with gold threads from my mother’s cupboard of scarves and hats. Thanks to this elegantly wrapped headscarf, I was transformed into the very pregnant Mary in no time at all. With the help of the big sofa cushions, I grew a huge baby bump in seconds. Since Joseph was nowhere to be seen, I got on the back of my donkey and set off on the arduous journey to Bethlehem where, finally – and this was the best part of the game – my baby doll miraculously saw the light of day.

As I got older, this game lost its appeal and I didn’t think about it anymore. At university, during my gender studies course, I was more concerned with whether girls should wear pink clothing and whether gender stereotypes are created through upbringing or genetics. We learned all about gender-appropriate education in kindergarten, and I thought about how to prevent children from growing up with entrenched role models. Today, these thoughts seem banal to me in view of the real difficulties my son has to deal with. How important can it be whether girls want to be hairdressers and boys want to be doctors, when my eight-year-old son wears nappies and has to be fed? Does it matter whether men and women work in the care sector and whether people say “nurse” or “male nurse” and “female nurse”? Of course, I am still aware of all these things that seemed important to me at the time, but my interests and priorities have shifted.

When I was in my early twenties, an elderly relative at a family party asked me what I wanted to do for a living when I grew up. I was studying at university, after all. On the one hand, I didn’t have the slightest idea what I actually wanted to do after graduation and, on the other, the question annoyed me a little. So, I said the most absurd thing that came to mind at that moment: I said I was going to be a housewife and mother. My own mother later complained to me about the cheeky answer. Today, when I think back to that answer, I’m surprised to find there was some truth in this idea of the future that seemed so absurd to me at the time. Today, strictly speaking, I am a housewife and mother, even if I like to jokingly call myself Theodor’s manager or the head of our own PR agency.

When I was twenty, my sister had a child. At that time, I had been studying in Vienna for two years and only saw my nephew, Noel, on weekends and holidays. Nevertheless, we had a close relationship. Six months later, I also had a new addition to the family, namely an eight-week-old puppy called Jimmy. Although my nephew was only six months old, the pair became the best of friends and Noel had the most fun messing around with the puppy. We would make up funny songs about Jimmy, the cutest dog in the world, and could spend hours dressing up and snapping funny photo series of us. I thoroughly enjoyed my time with my nephew. As he got older, we threw sticks for Jimmy in the meadow, played tag and went in search of one of the many secret hiding places that my nephew instantly found in every bush and behind every shrub. He loved it when I snipped around in his white-blond hair with the scissors and cut him fancy hairstyles using the electric hair-clippers.

Noel got really upset when he was going through his family phase, and wanted to know whether every animal we saw was a mummy or a daddy duck, and I desperately tried to explain to him that not every female animal is automatically a mummy and not every male animal is automatically a daddy. And at kindergarten he proudly spoke during the break about his aunt in Vienna who didn’t have a husband, but had a dog. I was the cool aunt in the big city who rode a motorbike and played the drums. I took Noel to our rehearsal room, where he was allowed to hammer on my drums with noise-protection headphones, and I let him sit on my parked motorbike.

In winter, we made up imaginative role-playing games at the playground. We played that we lived high up on the little hill and had to sledge down to the valley every day to go ice fishing on the frozen lake, which was actually the puddle of dirt next to the climbing frame. We hacked small holes in the frozen puddles with our shoes and let long sticks hang in the water in order to catch our dinner. The fact that our shoes were soaked-through afterwards was somehow part of the game.

We took my dog on long reconnaissance tours in the meadow, let him bathe in the duck pond and discovered secret places in the forest that could only be reached by climbing over the low wooden fence next to the path. We found a small stream that flowed into an old wooden gutter and, from there, into one of the many castle ponds. Running alongside the wooden gutter was a narrow wooden footbridge that led over a deep ditch into the forest. The wooden footbridge was so narrow and rotten that every step was a risk. Nevertheless, we tiptoed our way over it with the utmost caution. We then collected nettles with which to make a soup. I secretly disposed of these at home because Noel had picked some poisonous plants and leaves.

All those games I played with my nephew in my early twenties have no meaning for my own son. Yet, if I’d had any idea of what I would like to do with my child, it was those games that I’d have envisioned. I loved spending time with my nephew but, for some reason, I had never imagined being a mother myself.

When I first felt the desire to have a child, at the age of 27, the feeling was so strong and earth-shattering that it was all I