15,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: John Wiley & Sons

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

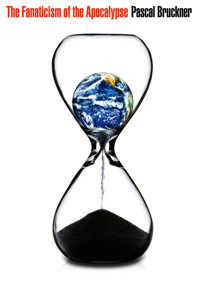

The planet is sick. Human beings are guilty of damaging it. We have to pay. Today, that is the orthodoxy throughout the Western world. Distrust of progress and science, calls for individual and collective self-sacrifice to ‘save the planet’ and cultivation of fear: behind the carbon commissars, a dangerous and counterproductive ecological catastrophism is gaining ground.

Modern society’s susceptibility to this kind of thinking derives from what Bruckner calls “the seductive attraction of disaster,” as exemplified by the popular appeal of disaster movies. But ecological catastrophism is harmful in that it draws attention away from other, more solvable problems and injustices in the world in order to focus on something that is portrayed as an Apocalypse.

Rather than preaching catastrophe and pessimism, we need to develop a democratic and generous ecology that addresses specific problems in a practical way.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 306

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Ähnliche

Table of Contents

Cover

Dedication

Title page

Copyright page

Epigraph

Introduction: The Return of Original Sin

Part I: The Seductive Attraction of Disaster

1 Give Me Back My Enemy

Farewell to insouciance

The candidates for a successor

The offence against Gaia

2 Have the Courage to be Afraid

Maximal indictment

Trained to panic

The return of the grim reaper

The limits of the horror show

3 Blackmailing Future Generations

The voluptuous pleasure of the state of emergency

The art of distracting attention

The breast-beaters

Part II: Progressives Against Progress

4 The Last Avatar of Prometheus?

The inevitability of forward movement

Intermittent lights

Do we control the weather?

The living, a subject with rights?

5 Nature, a Cruel Stepmother or a Victim?

On the bucolic as reconstruction

Zoophilia, theoretical and practical

Nature is not our guide

6 Science in the Age of Suspicion

The universe of evil spells

The imaginary doctor

The panic of reason

Scientists tell us that…

The fourth copernican revolution

Saving the spirit of exploration

Part III: The Great Ascetic Regression

7 Humanity on a Strict Diet

An ethics of renunciation

Impoverish yourself!

The preachers of austerity

8 The Poverty of Maceration

The sacredness of manure

For a politics of lightness

The commissars of carbon

9 The Noble Savage in the Lucerne

The golden age rediscovered

We have to cultivate our gardens

Humankind diminished or humankind expanded

A fear of movement

Epilogue: The Remedy is Found in the Disease

To my children, Eric and Anna, who have given me such joy

First published in French as Le fanaticisme de l’Apocalypse © Éditions Grasset & Fasquelle, 2011.

This English edition © Polity Press, 2013

Polity Press

65 Bridge Street

Cambridge CB2 1UR, UK

Polity Press

350 Main Street

Malden, MA 02148, USA

All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purpose of criticism and review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher.

ISBN-13: 978-0-7456-6976-2

ISBN-13: 978-0-7456-7014-0 (Multi-user ebook)

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

The publisher has used its best endeavours to ensure that the URLs for external websites referred to in this book are correct and active at the time of going to press. However, the publisher has no responsibility for the websites and can make no guarantee that a site will remain live or that the content is or will remain appropriate.

Every effort has been made to trace all copyright holders, but if any have been inadvertently overlooked the publisher will be pleased to include any necessary credits in any subsequent reprint or edition.

For further information on Polity, visit our website: www.politybooks.com

The world will come to an end. The only reason it might last is that it exists. How weak this reason is compared to all those that herald the contrary […] we will perish for the very reason we thought we would live. Machinery will have Americanized us so much and progress will have so fully atrophied our spiritual side that nothing in the utopians’ bloody, sacrilegious or anti-natural dreams will be comparable to its positive results.

Baudelaire, Fusées

Why make us fear our lives?

Voltaire, contra Pascal

Introduction

The Return of Original Sin

In Jesuit schools we were urged to strengthen our faith by spending time in monasteries. We were assigned spiritual exercises to be dutifully written in little notebooks that were supposed to renew the promises made at baptism and to celebrate the virtues of Christian love and succour for the weak. It wasn’t enough just to believe; we had to testify to our adhesion to the Holy Scriptures and drive Satan out of our hearts. These practices were sanctioned by daily confessions under the guidance of a priest. We all probed our hearts to extirpate the germs of iniquity and to test, with a delicious thrill, the borderline separating grace from sin. We were immersed in an atmosphere of meditative reverence, and the desire to be good gave our days a special contour. We knew that God was looking down on us indulgently: we were young, we were allowed to stumble. In his great ledger, he wrote down each of our actions, weighing them with perfect equanimity. We engaged in refined forms of piety in order to gain favours. Regarded from an adult point of view, these childish efforts, which were close to the ancients’ spiritual exercises, were not without a certain nobility. They wavered between docility and a feeling of lofty grandeur. At least we learned the art of knowing ourselves, of resisting the turmoil of puberty.

What a surprise to witness, half a century later and in an agnostic society, the powerful return of this frame of mind, but this time under the aegis of science. Consider the meaning in contemporary jargon of the famous carbon footprint that we all leave behind us. What is it, after all, if not the gaseous equivalent of Original Sin, of the stain that we inflict on our Mother Gaia by the simple fact of being present and breathing? We can all gauge the volume of our emissions, day after day, with the injunction to curtail them, just as children saying their catechisms are supposed to curtail their sins. Human beings are held responsible for all the damage they inflict on their habitat. A change of scale: alongside the oppressed and the humiliated with whom we are already familiar, a new figure makes its entry on the stage of History: the Earth. Our task is to prevent this cradle from becoming our collective coffin.

Ecologism, the sole truly original force of the past half-century, has challenged the goals of progress and raised the question of its limits. It has awakened our sensitivity to nature, emphasized the effects of climate change, pointed out the exhaustion of fossil fuels. Onto this collective credo has been grafted a whole apocalyptic scenography that has already been tried out with communism, and that borrows from Gnosticism as much as from medieval forms of messianism. Cataclysm is part of the basic tool-kit of Green critical analysis, and prophets of decay and decomposition abound. They constantly beat the drums of panic and call upon us to expiate our sins before it is too late.

This fear of the future, of science, and of technology reflects a time when humanity, and especially Western humanity, has taken a sudden dislike to itself. We are exasperated by our own proliferation, and can no longer stand ourselves. Whether we want to be or not, we are tangled up with seven billion other members of our species. Rejecting both capitalism and socialism, ecologism has come to power nowhere (except in one German Land) and has never shed blood, at least not up to now. But it has won the battle of ideas. Taking advantage of the failure of its predecessors – Marxism, Third-Worldism – it is triumphant, by capillary action, at the UN, in governments, in schools. It has become the dominant temper of the dawn of the twenty-first century. It excels more in preventing than in proposing: it closes factories, blocks projects, forbids the construction of super-highways, airports, railway lines. It is the power that always denies. Where it has become a political force, it always breaks up into cliques or factions that hate each other and fall prey to the narcissism of small differences: the greater the complicity, the more bitter the hostility. Here as elsewhere, it is always the most vehement who win out, inflecting doctrine toward the extreme. The environment is the new secular religion that is rising, in Europe at least, from the ruins of a disbelieving world. We have to subject it to critical evaluation in turn and unmask the infantile disease that is eroding and discrediting it: catastrophism.

There are at least two ecologies: one rational, the other nonsensical; one that broadens our outlook while the other narrows it; one democratic, the other totalitarian. The first wants to tell us about the damage done by industrial civilization; the second deduces from this the human species’ guilt. For the latter, nature is only a stick to be used to beat human beings. Just as Third-Worldism was the shame of colonial history, and repentance was contrition with regard to the present,1 catastrophism constitutes the anticipated remorse of the future: the meaning of history having evaporated, every change is a potential collapse that augurs nothing good. Its favourite mode of expression is accusation: revolutionaries wanted to erase the past and start over from zero; now the focus is on condemning past and present wrongs and bringing them before the tribunal of public opinion. The eighteenth century had acquitted human beings and declared them innocent; we are reopening old cases, reactivating all the indictments. Now no leniency is possible; our crime has been calculated in terms of devastated forests, burned-over lands, and extinct species, and it has entered the pitiless domain of statistics. The wrong no longer proceeds from nature, from political or religious fanaticism; it is born of the Promethean ambition of the individual who has ravaged the planet. The recent history of Western culture is nothing less than the simultaneous piling up of forms of guilt and liberation: we emancipate, on one hand, in order to lock up, on the other; we destroy taboos only in order to forge new ones. Prohibition shifts to a new object but never disappears.

The prevailing anxiety is at once a recognition of real problems and a symptom of the ageing of the West, a reflection of its psychic fatigue. Our pathos is that of the end of time. And because no one ever thinks alone, because the spirit of an age is always a collective worker, it is tempting to give oneself up to this gloomy tide. Or, on the contrary, we could wake up from this nightmare and rid ourselves of it.

Note

1 I have discussed these two subjects in Tears of the White Man: Compassion as Contempt, trans. William R. Beer (New York: Free Press, 1986) and The Tyranny of Guilt: An Essay on Western Masochism, trans. Steven Rendall (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2010).

Part I: The Seductive Attraction of Disaster

1

Give Me Back My Enemy

We all live in a house on fire, no fire department to call; no way out, just the upstairs window to look out of while the fire burns the house down with us trapped, locked in it.

Tennessee Williams

O God, show me the enemy. Once you find out who the enemy is, you can kill him. But these people here they confuse me. Who hurt me? Who spoil my life? Tell me who to beat back.

V.S. Naipaul

It happened in 1989, and that seems centuries ago. The world was emerging from the Cold War; the USSR, exhausted, was allowing subject peoples to escape its rule and preparing for its transition to a market economy. Euphoria reigned: Western civilization had just won by a knockout, without having had to go to war. Twice, in the course of the past century, it had triumphed over its worst opponents, fascism and communism, two illegitimate children to which it had given birth and which it was able to suffocate. At that time, anyone who expressed reservations or emphasized that it was less a victory of capitalism than a defeat of communism was accused of being a killjoy.

Farewell to insouciance

However, at the very moment when the Soviet system was playing a nasty trick on us by bowing out, enthusiasm was vying with fear: an adversary is a security against the future, a permanent competitor who forces us to reshape ourselves. Though we can never be sure of the affection of those closest to us, we can always count on the hatred of our enemies. They are the guarantors of our existence, they allow us to know who we are. Their aversion is almost a form of homage. Not to inspire any antipathy is to enjoy the tranquillity of the insignificant.

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!