Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- E-Book-Herausgeber: Orenda BooksHörbuch-Herausgeber: Isis Audio

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Serie: The Chastity Reloaded series

- Sprache: Englisch

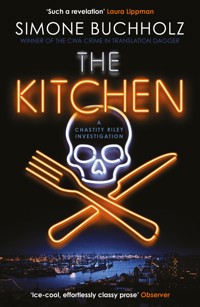

Hamburg State Prosecutor Chastity Riley and her colleagues investigate the murders of men with a history of abuse towards women … as a startling, horrifying series of revelations emerge. Germany's Queen of Krimi returns with the darkly funny, mesmerizingly dark next instalment in an addictive series… `Blends black comedy with real anger to produce a serious indictment of the male gaze. Simone Buchholz can make you grin, gasp or gag at will' The Times `Such a revelation´ Laura Lippman 'A dark treat … memorable modern noir, and a fascinating portrait of seedy life in Hamburg' Telegraph 'Beautifully concise, with commendably sparse prose, dark humour and an appealing protagonist … uncompromising, provocative and righteously fierce' Guardian **Book of the Month in The Times, Guardian and Literary Review** ________ When neatly packed male body parts wash up by the River Elbe, Hamburg State Prosecutor Chastity Riley and her colleagues begin a perplexing investigation. As the murdered men are identified, it becomes clear that they all had a history of abuse towards women, leading Riley to wonder if it would actually be in society's best interests to catch the killers. But when her best friend Carla is attacked, and the police show little interest in tracking down the offenders, Chastity takes matters into her own hands. As a link between the two cases emerges, horrifying revelations threaten Chastity's own moral compass, and put everything at risk… ________ 'Beautifully written in cool, witty prose' N.J. Cooper, Literary Review `German-American Chastity Riley [is] snooty, churlish, sarcastic, sometimes drunk and always inappropriate. The whole series breaks the boundaries of typical crime novels´ Romy Hausmann `A distinctive voice, and a flawed but compelling protagonist. This is vintage Buchholz – style and sass and St Pauli´ Will Carver Praise for the Chastity Riley series ***WINNER of the CWA Crime Fiction in Translation Dagger*** ***WINNER of the German Crime Book of the Year Award*** `Ice-cool, effortlessly classy prose´ Observer `Reading Buchholz is like walking on firecrackers´ Graeme Macrae Burnet `Gruesome and assured, Buchholz's work remains as persuasive as ever´ Financial Times `Simone Buchholz writes with real authority and a pungent, noir-ish sense of time and space … a palpable hit´ Independent `With brief, pacy chapters and fizzling dialogue, this almost feels like American procedural noir and not a translation´ Maxim Jakubowski `There is a fantastic pace to the story … a unique voice that delivers a stylish story´ NB Magazine `A smart and witty book that shines a probing spotlight on society´ CultureFly `A must-read, stylish and highly original take on the detective novel´ Judith O'Reilly `A real blast of adrenaline´ Big Issue `Elmore Leonard fans will be enthralled´ Publishers Weekly `Buchholz doles out delicious black humour [and] ramps up the intrigue and tension´ Foreword Reviews `Fierce enough to stab the heart´ Spectator `A modern classic´ CrimeTime `A stylish, whip-smart thriller´ Herald Scotland

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 207

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das Hörbuch können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

When neatly packed male body parts wash up by the River Elbe, Hamburg State Prosecutor Chastity Riley and her colleagues begin a perplexing investigation.

As the murdered men are identified, it becomes clear that they all had a history of abuse towards women, leading Riley to wonder if it would actually be in society’s best interests to catch the killers.

But when her best friend Carla is attacked, and the police show little interest in tracking down the offender, Chastity takes matters into her own hands and as a link between the two cases emerges, horrifying revelations threaten Chastity’s own moral compass … and put everything at risk.

The award-winning, critically acclaimed Chastity Riley series returns with a slick, hard-boiled, darkly funny thriller that tackles issues of violence and the difference between law and justice with devastating insight, and an ending you will never see coming…

v

THE KITCHEN

SIMONE BUCHHOLZ

TRANSLATED BY RACHEL WARD

vii

So, tell me now:

How far would you go for your girlfriends? viii

CONTENTS

The room is fully tiled, in a pale, matt grey. Cool. Modern. The units and worksurfaces, the pots, the pans and the bowls are stainless steel. In the centre is an island consisting of two massive gas hobs with four rings each. To the left, set into the floor: a drain.

There are two women in about their mid-thirties. One has dark-blonde curls in a messy bun. She’s wearing an aggressive knee-length dress. The other seems more serious. She is tall and thin, her pale-blonde, shoulder-length hair is tightly plaited, low on the nape of her neck, she’s wearing well-cut jeans and a fitted, dark T-shirt. She’s calling the shots.

She seems to be the one who knows what she’s doing.

The woman with the curls is pouring red wine into a large pan; in the pan are lumps of meat the size of cigarette packets. The chef is marinating cutlets in oil and herbs, and stacking them in a bowl. There’s fresh mince dropping through two holes in a machine into a large tub.

Nobody is in the kitchen but the women. The digital wall clock reads 3:37.

‘What d’you think?’ the one with the curls asks.

‘We’ll be done by six,’ says the other, wiping the sweat from her brow with a thin, grey towel.

BODY PARTS, WE DON’T HAVE THE DETAILS YET

The air in my fucking office is so thick, you could plait it into a ship’s cable. It’s hot in Hamburg. The temperature’s been over thirty every day for a week. And now, this lunchtime, the city’s adding a degree or two to that.

I sweep my hair out of my face and tie it up in a knot on the back of my head. I undo a few more buttons on my shirt, roll up my sleeves and turn my desk fan up from two to three. Then I drink a gulp of water, light a fresh cigarette and carry on. I’m devouring files: next week, three sex traffickers are up for trial. These guys travelled to Romania and spun village girls tales of ponies, of fantastic jobs abroad, as dancers, waitresses, au pairs. When the young women subsequently arrived in Hamburg, they were relieved of their passports and sent to work in shabby backstreet brothels in the Kiez. The scrotes carried on like this for years until we got wind of it. The usual. Somehow, no one ever notices until way too late when women or children are being abused.

Nobody ever notices in time.3

I can’t make up for the fact that we left the women hung out to dry for so long. But I’m going to be more prepared for this trial than I’ve been in my entire life. Those lousy arseholes are going to be facing the most merciless state prosecutor that a bunch of lousy arseholes has ever faced. When I’m done with them, they’ll curse the day they ever got the idea of trading in people.

The women we found in a dark flat on Kastanienallee had been treated like slaves. They were all ill. The clients had been allowed to use them without condoms at thirty euros a go, and they’d all left them some nice memento or other. On top of which, four of the five women had infected wounds on their bodies and faces. And two had children, who lived in this hell with them.

Sometimes, the faces of the dead follow me, but that usually stops after two or three nights. The faces of these young women have been visiting me in my dreams for six weeks now. The fear in all their eyes. Desperate. Degraded. Beaten. And the way the children stared. As if, on one hand they didn’t understand any of it, but on the other, they understood everything. Was that life? That shabby, dark hole?

My phone rings. It’s Brückner.

‘Rothenburgsort, boss,’ he says, ‘we’re just setting off. Coming?’4

He sounds flustered. Calabretta’s still on holiday and Faller’s position is yet to be filled. Inspectors Brückner and Schulle are on their own. Up to their arses in stress, the entire time.

‘Course I’m coming,’ I say. ‘What’s going on?’

‘Body parts,’ he says, ‘we don’t have the details yet.’

‘Where?’

‘The Billwerder Bay barrier. Want a lift?’

‘I’ll be with you in five.’

I switch off the fan, grab my cigarettes, my lighter and my sunglasses, and walk out. I ponder phoning Calabretta. Body parts might prove a bit much. If I call him, he’ll break off his holiday. If I don’t call him, I’ll be the senior investigating officer till he gets back.

I don’t call him.

SUMMER RETREAT, ROTHENBURGSORT

Brückner’s taken charge at the crime scene, he’s asking the questions. I’m not so keen on talking, anyway. Schulle has disappeared off behind a police car for a moment and is clearly getting shot of his breakfast. I light a cigarette.

SOCO are still sealing off the area. They’ll shoo me away in a minute. I’m loitering on a strip of grass that runs down to the water, there’s a solitary mansion behind me. The house is in good condition, painted a bright yellow, the new windows gleaming in the sun. The garden’s more like a small park. I didn’t know there were people with money in this neck of the woods. There’s another mini-mansion a little further on, smaller, not quite as grand, more delicate, like a summer retreat. But it’s also had a fresh coat of white paint not too long ago. Opposite, there’s a decaying old shipyard with junk piled everywhere; to my right, the tidal barrage slams into the blue sky. The thing looks a bit like a refinery, like a mini-factory. To my surprise, I find the whole effect rather beautiful. Maybe we should 6come out to Rothenburgsort more often. I’ll have to mention it to Klatsche and Carla.

It’s hot.

Lying on a quay wall about two metres from me is the black bin bag that’s brought us here. I’d hoped that my cigarette smoke would mask the stink a bit. Sadly, it doesn’t work. The sack must have been in the water a while and the contents have been merrily rotting away.

‘Sorry, Ms Riley, we kind of have to seal this area off now. Could you go and finish your smoke over there?’

Yeah, yeah, sure, fine.

WHAT’S WRONG WITH YOU

I get a couple of uniformed colleagues to drop me off in the Speicherstadt. There was quite a kerfuffle at the crime scene, and then the divers on top of that, plus the constant heat. When you’re hanging around somewhere like a spare part, you soon start to get on people’s nerves. And somebody has to check on Faller.

Since he retired three months ago, Faller has always sat in the exact same place, and he’s sitting there right now – at the foot of the lighthouse. The lighthouse is in the port, at the tip of a little spit of land. Faller says that he sits there, from dawn to dusk, for fun. I don’t believe a word of it. Faller’s never liked sitting around anywhere.

Calabretta says that Faller sits there because he’s trying to clear his head of the last thirty years, and I think he’s on to something: the old man has got to sit there. Otherwise, he’d be pottering comfortably around at home, reading the paper in peace and watching the things in his garden grow. The stuff you do when you’ve taken early retirement, when you’re sick and tired of it all.8

I turn left, past the Kaispeicher. You can see the little red-and-white-ringed lighthouse from miles off. It always seems like it’s made of Lego, sitting there so small and cute and so utterly pointless, looking over the massive port basin, all the container ships, cranes and huge brick buildings. Nobody actually has any use for it, apart from Faller of course; it’s quite clear that he needs it.

The path to the lighthouse isn’t paved, and the heat’s made it dusty. Good job I’ve got boots on. I feel like Clint Eastwood in person.

Two weeks ago, when it poured for days on end, this was an ugly swamp. And I felt the same way then – like Eastwood, that is, not like a swamp.

Faller’s sitting on a folding chair, he’s wearing a white shirt and grey suit trousers. He’s hung the jacket over the back of the chair and he’s swapped his old fedora for a straw hat, to keep the sun off.

There’s a fishing rod in his hand.

That’s new.

‘Faller?’

He turns his head, looks at me and pushes his hat up with his index finger, just a few centimetres.

‘What’s all this fishing-rod shit about?’ I ask.

He looks back at the water.9

‘You’re surely not going to tell me you catch any fish here, old man.’

He leans back in his seat and sighs.

‘And what if you do catch anything?’ I ask. ‘Where are you going to put it? I can’t see a bucket or anything.’

Faller looks at the water.

‘Want me to get you a bit of bait, at least?’

He looks at me as if I’d asked him if he wants me to get him some coked-up teenage whores, at least.

‘That was a serious question,’ I say, ‘you’re not going to get much for supper like this.’

He stretches out his hand, I sit down beside him on the dusty ground and he puts his arm around my shoulders. My God, it’s hot here, why the hell hasn’t Faller got heatstroke hours ago? A paddle steamer goes past beneath our noses. It makes me think of Belhaven in the Deep South, my dad’s home town.

‘Everything here is just as it should be,’ says Faller.

‘Why don’t I believe that?’

Instead of answering, he pulls two Roth-Händles out of his shirt’s breast pocket. The pocket covers the exact spot where the bullet went in. He got seriously lucky. Sometimes, I wake up in the morning with the feeling that he’s not here. That his heart didn’t actually make it. At those times, I try not to call him – I don’t want to 10bother him with his own death first thing in the morning.

He pops both the cigarettes in his mouth, pulls a lighter from his trouser pocket, lights them, hands me one and says: ‘You ought to get back to smoking more.’

I drag on the Roth-Händle, which makes me cough.

We stare at the water for a while, smoking.

‘So, my girl,’ he says, ‘what’s up?’

‘We’ve found a head,’ I say.

‘Oh.’

‘And some feet and hands.’

‘Double-oh. Man or woman?’

‘Man,’ I say.

‘Just lying around?’

‘No, it was all neatly packaged up in a bin bag in the Billwerder Bay. Along with a couple of heavy stones to stop the parcel from floating.’

‘So why did it surface then?’

‘They’re dredging,’ I say. ‘Clearing silt. The dredger guy got a surprise when he opened the bag.’

‘Bugger. How’s he doing?’

‘I don’t think he was that fussed. He was sitting around in the police car, getting the sun on his bare belly and cracking jokes about the weather. Seems pretty robust. He says he pulled a woman out of the water a 11few years ago, just around the corner at the Moorfleet Dyke.’

‘And how did my lads handle it?’

‘OK,’ I say. ‘Schulle started off by throwing up behind the car.’

‘Calabretta?’

‘Still in Naples,’ I say, ‘he’s not back until Sunday.’

‘Aha,’ he says, taking off his straw hat and wiping away the beads of sweat with the back of his hand before putting it back on again.

‘Isn’t it a bit hot for you here, Faller?’

‘Nope.’

I don’t want to tangle with him again so I shut my mouth and just wait until I’m grilled through.

‘Body parts, uh-huh. What else?’

‘Nothing else,’ I say.

‘Sure?’

‘Sure.’

‘Hm,’ he says. ‘Sometimes, I get a funny feeling that there’s something wrong with you.’

Surely not, I think.

‘Well, the main thing is that there’s nothing wrong with you,’ I say.

I look at him and try to find something, a clue as to what keeps him sitting out here the whole time. But this 12face, which I know so well, this furrowed, friendly, fatherly phiz with the big nose and the tired eyes beneath the brim of his hat, this whole affectionate package, isn’t giving anything away, not for two cents.

I look back at the water, just as he’s been doing this whole time, and so we stare at the spot where the Elbe widens before eventually flowing into the sea at Cuxhaven and, as a couple of gulls sail towards the afternoon sun on the horizon between the dark-red Grosse Elbstrasse and the dark-grey docks, a cargo ship pushes its way along the channel from our left, almost soundless and the size of a multistorey car park.

LOVE IN THE TIME OF OPPRESSIVE HEAT

The thing that makes summer in Hamburg so special is that night is practically out of action. It only gets properly dark for a few hours between midnight and four in the morning – that just comes as standard between May and August, you can bank on it.

And then there are evenings like this. There’s something so particular about them that you truly have to keep your wits about you. Otherwise, you might quickly start to mistake this whole thing for somewhere Mediterranean, maybe even a city by the Mediterranean Sea, and then it comes as a big shock when it’s raining again the next morning and the city’s only Hamburg after all.

An evening like this laps around your body like warm milk, with none of the stuff that tends to make the weather here such hard work. It’s half past nine.

After I saw Faller, I went back to the office to etch those victim statements onto my brain, ready for the trial. By Monday, I want to have them internalised so that I can 14summon them up at will. That should keep the rage on the boil.

I let Schulle and Brückner get on with the body parts for the time being. They’re going through our missing-persons files and we’ll meet up tomorrow morning at the police HQ.

These days, St Pauli smells not of sea air and the warm Elbe and dark corners, but of barbecue charcoal and firelighters and cold beer. There aren’t many gardens in this part of town, so the streets stand in for them, and here, on evenings like this, the St Paulianers sit, sweating and celebrating the summer and the fact that they are here in the world, on this very spot. Some of them sit outside the pubs in the official manner, on proper chairs and tables that are all duly licensed and paid for. But most people sit outside the pubs in the unofficial manner, on random armchairs that have just been carried out with nobody having paid anyone for anything. Other people just sit any old where on the pavements, outside bars and blocks of flats, and then there’s nothing but barbecuing and drinking and chatting. And in these temperatures, the Elbe’s always right at the tipping point, and somehow even that just fits in perfectly. Its weighty smell makes everything just a tad more humid.

I stop at a kiosk and buy another pack of cigarettes and a beer. From the street I can see my balcony; the junk-strewn 15thing next to it is Klatsche’s. Mine isn’t exactly any great shakes, the only things going on up there are a tattered pirate flag, a neglected grapevine and an old chair that’s been sat into oblivion. But Klatsche’s balcony is a disaster zone. If possible, it looks even more wrecked than his poor old Volvo, and that doesn’t have life easy. But then again, the Volvo only has to transport regular household rubbish; the balcony is lumbered with the bulky crap. Two and a half bicycles, a headless shop mannequin, five beer crates, a greasy barbecue from the summer of 2003, a broken TV. Two months ago, on one of the first nice evenings in May, Klatsche tried to invite me to sit out on his balcony. I asked him how that was supposed to work, and – at the very last moment, when he went to open the balcony door with two bottles of beer jammed under his arm – even he noticed that it might conceivably be a bit tricky.

‘Oh,’ he said, ‘I didn’t think of that.’

I didn’t say a word, just steered him out onto my own balcony and we sat there until the morning came creeping around the corner. We don’t make a habit of couply stuff like sitting around in places, staring out into the night. After all, we’re just two people who keep getting stuck on each other. Night owls, allies. But now and then, romance takes hold of us. Although it soon gets too much for us and we don’t know what we’re meant to do with it, and 16then it almost inevitably collapses and tastes flat, and we’re left standing around like a pair of idiots. That’s why we tend to prefer pub crawls and constantly resealing our friendship and going a couple of weeks without either of us stumbling into the other person’s bed. At times like that, Klatsche likes to stumble into other beds altogether, he says it happens by accident and he doesn’t mean to. I’m happy to believe the didn’t-mean-to part, but not the by-accident. Still, I try not to take it personally.

I unlock the street door, head up the stairs to the third floor where, instead of opening my front door, I knock on his. It takes a while, but eventually I hear shuffling, then a yawn, then the door opens. Klatsche’s wearing bright-blue boxers and a dark-green T-shirt that’s too small and a bit shabby round the neck. The fag in his hand must have gone out some time ago. He looks like a bandit.

‘Hey, Madam Prosecutor.’

‘Hey,’ I say. ‘What’re you up to?’

‘I’m lying in front of the open fridge.’

‘Mind if I join you?’ I ask.

‘Sure, I’m not going to let my girl peg out in this heat.’

He pulls me through the door and drops a kiss on the top of my head.

‘I’m not your girl,’ I say.

‘I know, baby, I know.’

I DON’T WANT TO BE ANYWHERE HIPSTER COUPLES GO

Brückner and Schulle look like they’ve just come in from the playground. One’s wearing a thin T-shirt and the other’s got his threadbare Liverpool shirt on, they both have uncombed hair kind of pushed out of their faces – Brückner’s goes more back, while Schulle’s goes more up – and the bright, northern-European sun is shining out of their faces. Like they’ve been on holiday to Seacrow Island. I’ve really grown to like these two, the way I used to like the boys in the back row at school.

‘Moin, boss,’ says Schulle, raising a hand; Brückner grins and picks his nose, probably without even noticing.

I often wonder what these guys would do with themselves if they had to wear uniform.

‘Moin, gentlemen,’ I say. ‘How’s business?’

‘Tidy,’ says Brückner. ‘We know who we pulled out of the water yesterday.’

‘Oh, that was quick work. Who is it?’

‘Dejan Pantelic,’ he says. ‘Aged thirty-one, professional 18musician. Came to Hamburg from Belgrade in the mid-nineties. No family left here. His girlfriend reported him missing on Monday this week.’

Pinned to the wall behind his desk are the photographs taken in pathology of the head from the Billwerder Bay. Next to them is a slightly scruffy picture of a guy in shorts and a Hawaiian shirt. He’s standing beside a palm tree with a cocktail in hand and a look on his face that suggests he thinks pretty highly of his own appearance. With the best will in the world, I can’t see much resemblance between him and our head.

‘The same guy?’ I ask. ‘Are you sure?’

‘He’s just a bit swollen,’ says Brückner. ‘His girlfriend identified him this morning, without a shadow of a doubt.’

‘Oh,’ I say, ‘that can’t have been very nice.’

‘Schulle did it,’ he says.

‘Oh,’ I say again.

And Schulle says: ‘Got to be done. That was my first floater, and it wasn’t even in one piece. But it’ll be OK.’

Brückner yawns and digs around in his nose again. There’s something up there.

‘So how many have you seen?’ I ask him.

‘No idea,’ he says nasally. ‘I trained on missing persons. We were constantly pulling people out of the water. Kind 19of routine. My God, the sight of them. Yesterday’s was a piece of piss in comparison.’

Really.

‘So, what else do we know about this, what was his name again?’

‘Pantelic,’ he says. ‘He was last seen Friday night or the early hours of Saturday morning, in the Kiez. Went to the Silbersack with two mates, and they reckon he headed home around two. Or that’s what they told his girlfriend, anyway. We haven’t had a word with the mates yet, but I will in a bit.’

‘OK,’ I say. ‘What else have we got?’

‘The divers didn’t find a thing,’ says Schulle, packing up his stuff. ‘The Elbe is somewhat less than crystal in this heat. SOCO found plenty of fag ends and hairs and tyre tracks in the grass where they dredged him up, but they won’t get us very far. The whole Billwerder Bay is kind of a hang-out for hipster couples at the weekend.’

Damn. OK, maybe we won’t be heading out to Rothenburgsort more often then. I don’t want to be anywhere hipster couples go.