7,19 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Allison & Busby

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Serie: Nighthawk

- Sprache: Englisch

Cambridge, 1940. It is the first winter of the war, and snow is falling. When an evacuee drowns in the river, his body swept away, Detective Inspector Eden Brooke sets out to investigate what seems to be a deliberate attack. The following night, a local electronics factory is attacked, and an Irish republican slogan is left at the scene. The IRA are campaigning to win freedom for Ulster, but why has Cambridge been chosen as a target? And when Brooke learns that the drowned boy was part of the close-knit local Irish Catholic community, he begins to question whether there may be a connection between the boy's death and the attack at the factory. As more riddles come to light, can Brooke solve the mystery before a second attack claims a famous victim?

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 422

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Ähnliche

3

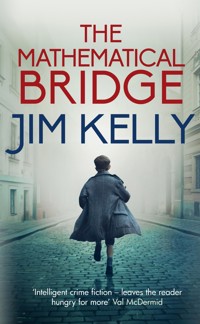

THE MATHEMATICAL BRIDGE

JIM KELLY

5

To Steve and Gabrielle Bennett for a friendship that stretches from Dryden, to Shaw, to Brooke

6

AUTHOR’S NOTE

The City of Cambridge is one of the principal characters in The Mathematical Bridge. Like all fictional characters it is a combination of fiction and reality, both in terms of its geography and history. I hope that, whatever the mixture of fact and imagination, the city’s spirit of place survives.8

CONTENTS

CHAPTER ONE

New Year, 1940 Cambridge

Detective Inspector Eden Brooke trudged into Market Hill, the city’s great square, as snowflakes fell, thick and slow, each one a mathematical gem, seesawing down through the dead of night. Every sound was muffled, a clock striking the hour out of time, the rhythmic bark of a riverside dog, the distant rumble of a munitions train to the east, heading for the coastal ports. The blackout was complete, but the snow held its own light, an interior luminescence, revealing the low clouds above. Brooke stopped in his tracks, his last crisp footstep echoless, and wondered if he could hear the snow falling; an icy whisper, in time with the sparkling of the crystals as they settled on the cobbles, composing themselves into a seamless white sheet.

In the sky to the south a pair of searchlights fidgeted, searching for the German bombers yet to come. Brooke thought of his son, 10Luke, with the British Expeditionary Force, camped out along the Belgian border, asleep now under the same weeping sky, waiting for spring, the thaw, and the first volley of shells from the east. The war was nearly five months old, and the clash of the Great Powers edged nearer every day, the so-called phoney war stretching out towards the inevitable breaking point.

Brooke walked on through a world he knew well: the city at night, a maze of stone and hidden places, a personal kingdom. He passed the bone-white marble columns of the Senate House and saw King’s Parade ahead, a great open thoroughfare, bordered on one side by a chaotic jumble of shops and inns, looking out across a wide snowfield to the stone traceries of the college buildings, and the soaring silhouette of King’s College Chapel. The scene was utterly quiet, frozen in the moment. He looked up, snowflakes falling wetly in his eyes, and saw the four great pinnacles of the chapel disappearing into the clouds, as if the building had been let down from the heavens on four stone hooks.

Brooke lit a cigarette, one of his precious Black Russians, and took in the arctic air laced with that strangely metallic edge, redolent of granite islands, and icebergs, and vast grey oceans. The snow, which had fallen now for three consecutive days since New Year’s Eve, covered everything in a single folded counterpane, partly obscuring a parked car, all the pavements, a few shop doorways, even the makeshift sandbag walls which had been set up to restrict bomb blast, should the long-awaited air raids finally materialise. Ice clung to the wooden boards which had replaced the stained-glass windows of the great chapel, whisked away to the safety of a city cellar.

Even in this soft light Brooke needed his tinted glasses to protect his damaged eyes: the ochre lenses tonight, providing a subtle filter which produced, for him alone, a gilded world. In 11his pocket, ready for use, were the green-tinted, the blue and the black. But the city at night had always been shadowy, even before the blackout, gas shortages enforcing ‘lights-out’ at ten o’clock for most of the years after the Great War. And, in truth, he didn’t need his eyes to find his way; he read these streets as if they were set out in Braille.

The silence was broken by the bell of Great St Mary’s marking the hour.

Brooke stopped at his usual spot, opposite the gatehouse of King’s College. He could just see a splash of yellow light on the stonework where the door of the porters’ lodge had swung open. A dark figure appeared with a shielded lantern and trudged off into the Front Court beyond to begin the ritual round of checking doors and windows, and looking out for chinks of telltale light from the rooms of scholars burning midnight oil. A cat, in pursuit, jumped from footprint to footprint, until they were both gone.

Brooke savoured the cigarette, admiring, as he always did, the way the gold filter paper caught the light. Drawing in the nicotine, he took a step forward, turned on his heel and examined the wall above his head, knowing what he’d find: a stone oval plaque which had hung there since he’d first spotted it as a lonely child wandering the city. The frost had clung to the letters, and the roughly hewn decorative symbols of a wine pitcher and a bunch of grapes.

Edward FitzGerald, poet, lived here: 1880–1891

He’d read FitzGerald’s masterpiece when he’d been a soldier in the desert during the Great War. The Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám, a translation of the Persian original, had replaced The 12Iliad in his kitbag. Each night, on the long march from Cairo across the northern Sinai with the Egyptian Expeditionary Force, he’d kept up his spirits with the poet’s gentle invitation to enjoy the day.

Be happy for this moment. This moment is your life.

Brooke bent down, made a snowball and launched it at the plaque. Given the horrors of that war, which he’d been lucky to survive, it was a philosophy that celebrated the life he lived.

The white silence stretched on. Perhaps it was the echo of the Rubáiyát, but the softly blanketed street reminded him of the desert, the blinding sands between Gaza and the sea which crept over villages and roads, encampments and trees, leaving them just like this: softened and wrapped, parcelled in curves.

It was the desert that had left Brooke a nighthawk, haunted by insomnia, the result of his capture and torture by the Ottoman Turks. Despite the pain – the light of interrogation in his eyes at night, the blinding sun in the day – he’d kept the secrets he had to keep. The king had given him a medal, but he’d never seen himself as a hero. By the fifth day he’d been unable to tell truth from lies. It all seemed like a long time ago.

He filled his lungs, held his breath, and felt certain something was about to begin. The unexpected bonus of his condition was this insomniac buzz: a hyperacuity, his senses operating at a preternatural level.

A moment before the sound itself, he heard its forward echo: the pip of a police whistle. Then three blasts, a pause, three more – the agreed signal.

Brooke ran to the corner of Kings Lane, the metal Blakeys on his shoes penetrating the snow to clash with the pavement 13beneath. He stopped, breathing hard, and heard the whistle again, but louder, and now the dot-dot-dot rhythm had gone. Narrow, cobbled under the snow, the dark passage led to the doors of Queens’ College below its three octagonal turrets.

PC Collins stood in the street, his black cape swinging as he turned left and right blowing his whistle.

Brooke slowed to a walking pace. The Borough police force was one of the smallest in the country. With only eighteen constables in uniform, he knew them all: Collins, just eighteen, was excitable and what Claire would have called ‘skittery’. Brooke detected a note of panic now in the manic whistling. What had unsettled the young constable? A fleeing figure – a student climbing back into his rooms after a secret assignation?

‘Collins,’ he said. ‘Calm down, lad. What’s happened here?’

Collins dropped his whistle on its cord.

Brooke slipped off his hat, folding it back into shape, replacing it with a downward tug of the forward edge. The great facade of the college looked supremely unruffled. His father had once brought him here to point out Erasmus’s rooms in the third high turret. A symbol of calm, reasonable logic.

Collins stood awkwardly at attention, breathing heavily.

‘Sorry, sir,’ he said, tongue-tied.

Brooke’s reputation went before him: brisk, unpredictable, unable to suffer fools. Getting in the detective inspector’s bad books was considered a fatal career move on the Borough. Collins, like the rest of the young constables, would be in the army by the spring if the war didn’t end. Like the rest he’d no doubt hoped for a quiet life until then.

‘What’s happened, Collins?’

‘Sir. I was knocking off, on my way home, when I saw the 14porter out in the street shouting. There’s a body in the river, sir, floating downstream. He’s ringing the Spinning House now, sir. I’ve asked for assistance.’

The Spinning House was the Borough’s headquarters, a medieval gaol less than half a mile away.

‘There’s two others out on night beat: that’s Jenkins and Talbot. I thought they’d hear the whistle.’

‘Good,’ said Brooke. ‘This body. Did he actually see it? Any signs of life?’

A blank stare told Brooke all he needed to know: Collins hadn’t asked.

‘When reinforcements arrive, send them down the river, to the Great Bridge, then Jesus Lock. If the body’s floating, that’s where it will go. The stream’s in flood. I’ll deal with the porter. Keep up the whistling. Just three blasts then silence. Got it?’

Collins nodded.

‘When the others are downriver you go up, check out the bridges. Start with Silver Street. See if anyone’s about.’

Collins looked like he was trying to memorise his orders.

Brooke stepped over the high sill through the miniature door set in the great wooden gates of the college and found the porter in his lodge.

‘I got through. They’re sending help,’ he said, standing, dropping the phone, his face utterly devoid of colour.

‘You alright?’ asked Brooke.

‘Follow me,’ he said, grabbing a storm lantern and a torch.

Front Court was a well of shadow, but Cloister Court emerged from the night because of its Tudor range of black timber on white plaster. Ahead, Brooke could just see the porter’s boots illuminated by the lantern, his footprints inky black.15

Under an archway with a single retching gargoyle’s head, they emerged over the river on the graceful arc of the Mathematical Bridge, built of straight wooden beams set at a tangent to create a curved span, and – according to disputed legend – built without a nail.

The porter, breathless, stood at the centre, holding the lantern out over the water. The Cam was wild, a chocolate-coloured spate swirling beneath their feet, the surface pockmarked with miniature spiral whirlpools. Occasional shards of ice swept by.

‘Right here,’ he said. ‘There was a sack, like for potatoes? It was gone in a second. I think he was struggling to get out. I heard a voice, sir. Clear as my own.’

‘What did it say, this voice?’

‘Help me. Help me. Just that. And the terrible thing is it was the voice of a child. A boy – I’d swear to it. Who could do that, sir – drown a child like a dog?’

CHAPTER TWO

Brooke ran back, crossing King’s Parade, where he heard more police whistles and saw a radio car in the distance, its feeble, swaddled headlamps myopic in the still-falling snow, disappearing towards the Great Bridge. Opposite Trinity’s gatehouse he turned sharply into the old Jewish ghetto, a maze-like neighbourhood of blind alleys, which he’d memorised as a child. Left, right, right brought him into a small yard where the snow had etched the outline of a series of noble heads in stone, supporting iron gutters.

The yard widened to reveal a college facade and a single great door. He executed the long-perfected late-night knock – two taps, a pause, one tap – using his signet ring against the iron hinge. Waiting, imagining the night porter’s stately steps, he looked up into the blizzard, each flake in shadow 17against the luminous sky above. He thought of the snow settling on the swirling river, the child struggling, the double suffocation of the sacking and the water, but most of all the bitter cold.

Doric, the night porter of Michaelhouse, stood in the open door, the great ring of college keys in his hand, turning away already to the interior of the lodge with its panelled walls and the orange glow of a coke fire. Here, on most nights, Brooke took refuge for warmth and the promise of a few leftovers from the kitchens or took a seat by the fire and read the college’s newspapers. Doric was one of Brooke’s faithful fellow nighthawks, condemned to live life out of the light, at home in the shadowy world of the college after dark, of which he was the undisputed master.

Doric picked up a kettle and set it on the stove.

‘Not tonight, Doric,’ said Brooke, still on the doorstep. Hat off, he ran a hand back through thick black hair which flopped forward over his forehead. ‘There’s no time. I need the keys to the college punt. A child’s in the water. We may have time, if we’re quick.’

Doric grabbed a single iron key from a hook.

‘What about Jesus Lock?’ he said, turning to a map on the wall which showed the tortured passage of the Cam through the city. ‘The river’s in flood; it may be open.’

If the lock was open the child might be swept out into the wider river and on towards the sea.

‘Ring the lock-keeper, Doric,’ said Brooke, resetting his hat. ‘If you can find a number. If not, ring the Spinning House, they’ll have it. There’s a cottage by the gates. Get them to close the sluice too. I’ll be there soon.’

‘Take this,’ added Doric, producing one of the college torches 18from beneath the counter and handing it over with the key.

Brooke ran back to the river, retracing his steps, almost lost in the falling snow. His blood raced, his heartbeat strained, and it made him consider again the child: its heart might be slowing, the blood too, collecting in the ice-cold limbs. Each minute that passed, he knew, took them further away from life. The river could not be more than a degree or two above freezing. The shock alone could be fatal.

Michaelhouse did not back onto the river like most of the other medieval colleges. However, there were plenty of keen college punters and rowers who liked to take to the water, and so a wharf was needed, beyond a locked door, where in the summer Brooke indulged his private passion for swimming in the river. Each night he’d slip into the green water, and slide unseen through the heart of the old city.

Tonight, the Michaelhouse punts lay in a frozen flotilla, chained and covered in a single blanket of snow.

Brooke tackled the icy padlock and set a punt free. As a student he’d been adept with the pole, guiding the flat-bottomed boat out past sun-splashed meadows into the countryside, where the shallow river ran in a shingle bed. Nevertheless, the frost made him clumsy, and he struggled to use the pole as a rudder, swinging out into the mainstream.

Doric’s torch picked out the stone canyon which here served as the river’s banks, the walls of colleges pressing in on both sides of this stretch of what everyone called the Backs. The beam of light caught flecks of falling snow; student rooms, shuttered and dark; a single owl in an empty carved niche, eyes wide. The current at the centre of the channel was rapid, but in the backwaters created by water gates and docks, steps and bridges, eddies swirled in confused circles. If the child was still 19afloat, the sack could have snagged anywhere, but there was no sign of life.

Blocks of ice bobbed in the muddy water. The cold river, caught between the damp college walls, had chilled the air. Brooke’s breath billowed out as he used the pole to steer under the string of stone bridges which served the colleges, until a sharp turn brought him to the Great Bridge itself, the old Roman crossing which had joined the lower town to the upper, clustered around the castle. From here it was a straight run to Jesus Lock.

On the bridge above, a constable stood, swinging a lantern.

‘No sign of the child,’ a voice called. ‘They’re shutting the lock, and Baits Bite too.’ Then Brooke was gone, swirling past under the echoing stone arch.

In summer the journey would have required him to use his weight on the pole, like a lever grounded in the gravel bed, to propel himself forward, but tonight the Cam was a torrent and so the river took him on at speed, and ahead he saw quite distinctly the white water of the approaching weir, to one side of the sluices and the lock.

His torchlight swept the flood, left to right, left to right. The river was black but threaded with whirling circles of silver bubbles. On the distant lock bridge, the keeper worked at an iron wheel, inching the sluice gates shut. A police constable, on the far bank, trained a torch on the water as it gushed through the narrowing gap, watching for the child.

The snowfall faltered; the moon appeared through a break in unseen clouds, shining over the wide, bubbling stream. The punt raced onwards, so that Brooke had to cling to the sides. His eyes scanned the water and, for a second, he almost missed 20it, something not moving with the flood: a glimpse of hessian; a hand, seeming to reach up, breaking the surface twenty yards ahead. In three tumbling seconds he was almost upon it, reaching out, knowing even in the moment that he was a yard short. In an effort to lock fingers to fingers he nearly tumbled out of the boat. Then he looked back, levelling the torch beam, but the hand was gone.

The punt dipped, swung and plummeted though the narrowing gates of the sluice. To the right he glimpsed the lock-keeper’s face, shiny with sweat, a hand raised, the eyes wide. Below the lock the cascading flood created a whirlpool, which spun the punt, with Brooke at its centre. Only now, slipping away from the lock, did he notice the thunder of the water as it diminished, leaving a strange, trickling calm. The lock was shut behind him. Had the child slipped through, or was he trapped in the river above?

‘Any sign?’ shouted the lock-keeper, a silhouette against the searchlight.

Brooke strained to catch the echo of a child’s voice, but all he heard was the strange Brrrr! Brrrr! of a distant nighthawk in the reeds. He swung the torch across the water’s surface.

‘Nothing,’ he said, in a whisper to himself.

CHAPTER THREE

Brooke deployed the meagre resources of the Borough to their limit. One radio car was sent to Baits Bite, the next lock downstream, to make sure its sluices were shut too and that they stayed shut, while preparations were made to dredge the whole river at dawn, down from the Mathematical Bridge. Where to concentrate the search? It was probable the child had been swept through the sluice into the lower river with Brooke and the punt, although the locks had been closing, and he might have been caught in the spiralling currents and swept into a side water, a backwater or a ditch.

The Borough’s night watch of six constables were set, three on either bank, to walk the mile from the Great Bridge to Baits Bite. The army’s motorised river patrol boat was allocated the upper river. A mobile searchlight from an ack-ack gun emplacement 22at Marshall’s airfield was trundled into place on the bank. After the white water fall between the sluice gates, the surface here was alive with bubbles, whirlpools and flotsam – twigs and branches, moss and reeds. Lights blazed in the riverside narrowboats and houseboats, their owners on deck, keeping watch. The WRVS, alerted to the emergency, had arrived with a mobile tea van at the lock gates.

With each quarter-hour chime of the city clocks, hope faded.

Brooke set up a command post of sorts in the lock-keeper’s cottage. While its exterior might be charming, its interior was utilitarian, the decoration strictly limited to the green and white livery of the Cam Conservators, the ancient custodians of the river, according to a brass plaque over the door. The front rooms were used to store spare ironwork for the locks, dredging hooks and large drums of lubricant oil for the sluices and gates. The lock-keeper, a widower, seemed to inhabit only a small rear kitchen with a cot bed and a pot-belly stove. But he did have a phone, a wall-mounted Bakelite model with a printed card fixed to one side listing numbers for the locks up and down the river.

Brooke set in motion plans for the day shift to continue the search. The unsaid question was implicit: the search for what? Not a child any more, but a body. There was little doubt the boy – the voice had been high, but definitely a boy, according to the porter – now lay on the riverbed, his lungs flooded with river water. It wasn’t just a search for a corpse – the victim’s identity would be a clue of itself. There might be more: wounds inflicted, clothes, the drawstring, the sack.

Brooke studied the lock-keeper’s chart under a bare light bulb. He’d swapped the ochre-tinted glasses for the green to reduce the painful brightness of the electric light.23

The chart showed the Cam, rising in the southern hills, curling around the city, before heading north to the Fens. The child had been thrown in the river – where? The answer had to be upriver of the Mathematical Bridge. Small tributaries – the upper Cam, the Granta, the Rhee – formed a network of streams and pools. How long could the child have stayed afloat before passing beneath the Mathematical Bridge? A few hundred yards, half a mile? By daylight the Borough’s radio cars would be assigned to bridges and villages upstream, just beyond the leafy suburbs of interwar semis, where house-to-house enquiries could begin. Had anyone heard a child’s cries? Had anyone lost a child?

The map’s filigree channels of river and stream, dyke and drain, began to swim before Brooke’s damaged eyes. Exhausted, he needed to find a place to rest. The best cure now for the pain was a walk beneath the cold stars, the darkness a salve. And he didn’t have to keep his own company, for the city was full of nighthawks, ready with a fireside, or tea, or whisky, and often advice, when a case proved intractable. Or even a couch, or an armchair, if sleep did fall as it often did, without warning, like a hammer blow.

So he abandoned the lock-keeper’s cottage and set off back into town. Parker’s Piece – the city’s great open park – was a ghostly encampment of white bell tents, an army camp since the first week of the war. A few fires burned in the gaps between the tents. With a jolt the scene reminded him of a night in 1934, when he’d been a detective sergeant, shadowing the hunger marchers from Jarrow. The ragged, jobless men had reached the city bounds at dusk. They’d been met with tea and buns at Girton College but with the stern indifference of the Borough when they got to Parker’s Piece. The sense in which his duty, and his sympathy, had pulled in opposite 24directions had left him wary of demonstrations ever since.

But here, in a military camp, he felt at ease. Claire always said he cut a determined figure: hat; broad shoulders, narrowing down to the feet, which seemed to coalesce at a single point, like a nail driven into the ground. A corporal in fatigues appeared with a torch and checked his warrant card, waving him on with a warning to tread carefully.

In five minutes, he reached the distant iron gates of Fenner’s cricket ground. The university’s pitch was untroubled by a single human footprint, although the spectral wings of birds, caught at the moment of take-off, dotted the outfield. A short street of large suburban houses led away into a cul-de-sac. The green door of the last house was always on the latch, so he opened it carefully and climbed two sets of stairs to a bedroom.

Detective Chief Inspector Frank Edwardes lay in his deathbed, propped up on a series of pillows, his grey marble skin catching the light of a candle set by a pile of books. The window, ajar to the frosty night air, gave a view of the ghostly cricket field. The moon, now that the clouds were clearing, cast a cold light, creating shadows of the leafless elms which circled the ground.

‘Eden,’ said Edwardes, suddenly opening his eyes.

They heard footsteps on the floor below. ‘That’ll be Kat making you tea.’

‘I’ve woken her,’ said Brooke.

‘I doubt that.’

Kat, Edwardes’ wife, was a nurse who’d worked with Claire and now cared for her husband.

‘Any news from the river?’ asked Edwardes.

Beside the bed, against one entire wall of the large bedroom, was a bank of radios. In peacetime, Edwardes 25had been a ‘ham’ – an amateur radio enthusiast – one of thousands across the country building simple transmitters, running networks, tracking exotic messages from Europe and beyond. War had brought a prohibition on all radios, which had to be handed in to what they were all learning to refer to as ‘the authorities’. There was one broad exception: any ham who agreed to monitor the airwaves for useful data, and send it promptly to the intelligence services, could keep their kit.

Edwardes tracked the Borough’s radio car transmissions along with the rest of the nightly ‘traffic’.

‘No news,’ said Brooke. ‘There’s no sign. I saw his hand, Frank. Nearly got him, but the current’s too strong, and the lock gates were open.’

‘Well done,’ said Edwardes.

‘For what?’

‘For not jumping in, Eden. No one likes a reckless hero. We all know you swim in the river. But not in the dark, not in freezing water, not in a flood – you had no chance.’

Brooke nodded in agreement. ‘You’re right. Too cold, Frank. Even for me. And the boy was gone in a moment. There’s ice now, great plates of it. Any colder, any longer, and the students will be out on skates.’

Edwardes lit a cigarette and threw his head back. ‘I’d like to see that again. That’s how I met Kat. Last winter before the Great War, out at Coe Fen. I fell over, she picked me up.’ His eyes fixed on the middle distance.

Returning from the sanatorium in 1919, Brooke had abandoned his studies at Michaelhouse to join the Borough, the damage to his eyes making extensive reading and laboratory research impossible. His father, a distant figure, had won a Nobel Prize for developing a serum for diphtheria, 26a breakthrough which had saved thousands of lives, possibly millions. Brooke, a hero of the war, still felt the need to carve out a sense of purpose from the peace. The police force had offered a chance to solve logical problems and serve the city he’d adopted as a lonely child.

Edwardes had been his mentor. They’d worked together for nearly twenty years, from war to war, policing the city in the age of the dole queue. Nine months ago, an unspecified canker had struck the old man down. Brooke now had his superior’s office, and would have had the rank, but he’d been in no hurry to step into a dying man’s shoes. The fiction that Edwardes would return, cured and in fine health, had been carefully maintained. His life would end in this room, and possibly before the first ball was bowled on Fenner’s in the spring.

A burst of Morse code filled the room and Edwardes took up a pad, effortlessly jotting down lines of apparently random letters in groups of five.

When silence fell, he studied the note, then laughed. ‘Not even in code,’ he said. ‘One of ours. It’s always one of ours. A ham out at Royston. He says he’s just picked up a message from Felixstowe that the sirens have sounded. Perhaps this is it at last, Eden. The real war.’

Brooke took the armchair as Edwardes began to describe the latest news from the BBC: fears over a German invasion of Norway, troop movements near the French border. His voice seemed to fade away, and when Brooke closed his eyes he tumbled backwards into a sudden sleep.

When he woke, twenty minutes later, Edwardes was reading. A cup of cold tea stood on the table beside Brooke.

Edwardes closed his book. ‘Tell me more about the child in the river.’27

‘Porter at Queens’ heard a voice cry out “Help me!” Just that. Swept past under the Mathematical Bridge in a sack. I’d guess he’d be four or five years old. A boy. There’s no hope, but it would be nice if there was justice. The problem is I can’t visualise the killer. Who could do such a thing?’

‘You’re right. It’s beyond understanding. That’s your problem – he’s the bogeyman, this killer of yours. He comes with a sack to take away naughty children, Santa Claus in reverse. A sack of toys for the good children, just a sack for the bad. If you think it through it says a lot. I’d focus on why, not who. The modus operandi is stark. You don’t just have a sack to hand. So, premeditation. And it’s ruthless, and pitiless, so I’d say it was professional. It’s not a domestic, is it? Where did he chuck him in?’

Brooke started to visualise the bridges upstream of the Mathematical Bridge: Silver Street, the Little Bridges, Fen Causeway …

The old man set down his pad with its scrawl of dots and dashes. ‘You’re not wandering round Cambridge with a child wriggling in a sack – are you?’ said Edwardes. ‘It’ll be a car, or a truck, with the kid in the back, probably unconscious. So he stops, slings the sack over the parapet and drives off. The icy water brings the boy round.’

‘God. What a thought.’

Edwardes sat up. ‘I’ll tell you this, Eden. Odds on he’s killed before. And you’ll know what that means. It’s a cliché, but it’s a brutal truth: if he has to, he’ll kill again.’

CHAPTER FOUR

At the Spinning House, Brooke slept for an hour in cell six, a stub of candle on a wooden ledge, the darkness like velvet lying on his eyes. Waking, he felt hungry. Claire worked the night shift at the city hospital and when they could they met for breakfast. Brooke shrugged himself back into his Great War trench coat, grabbed his hat and climbed the spiral metal staircase up to the Spinning House’s duty desk, where the sergeant reported no news from the river, except that the dredging was about to begin and that the banks had been thoroughly searched.

Brooke stepped out into Regent Street, the old Roman road which ran like an arrow into the city from the low chalk hills of Gog and Magog. The scene was utterly still. Dawn was in the eastern sky. He felt the familiar childhood thrill of having the city to himself, a plaything, a puzzle, a 29labyrinth. Opposite the police station stood the frontage of the Cambridge Daily News, where a single light shone at an upstairs office, and Brooke heard a telephone ringing unanswered. Next to the News stood the New Theatre, a dramatic confection of balconies and ironwork. Theatres had been reopened, along with cinemas, and he and Claire had got the last seats in the house the week before to see Gaslight. Brooke thought that was a luxury: a nice, neat murder, all tied up in one small house.

He set out for Addenbrooke’s Hospital, a half-mile, weaving through the university’s science district, a grid of cool, antiseptic brick blocks. He came out opposite the pillared splendour of the Fitzwilliam Museum, with its four sitting lions, which he’d climbed aboard as a child, until an irate curator had dragged him off. Opposite, he turned into the iron gates of the hospital, and looking up saw slivers of light where the blackout blinds had failed. Dawn was rising, casting gold on the steam and smoke billowing from chimneys and pipes.

Once inside, the corridors, glassy and lit, led Brooke to Admissions, his metal Blakeys sounding like gunfire on the polished lino. As he was in the building he felt standard procedure could not be ignored, so he tracked down the sister and told her about events on the river. Had anyone suspicious been seen overnight? They’d treated three cases after nine o’clock: two men who’d fought in the street outside The Eagle and inflicted identical cuts on each other with identical bottles, and an emergency appendectomy. Brooke asked if the Spinning House could be alerted to any admissions of children or victims of domestic violence. Was that the root of the crime, a family at war?

Brooke ran up the stairs to Sunshine Ward. The children were being woken up for breakfast. They lay in thirty iron 30bedsteads down each side of the long ward, a few feet apart. There was a drifting aroma of stewed tea and burnt toast, and somewhere a radio played the Home Service, a piece of dance band music. The sun, on cue, was beginning to stream in through the windows down one side.

‘You’re not supposed to be in here,’ said his wife, smiling, standing in front of him, holding a bedpan in the crook of her arm. Claire was the sister on the ward, having transferred from Geriatrics. Children were going to be part of their lives again in more ways than one; their daughter, Joy, a nurse herself, was pregnant and now at home after six months administering last-minute health checks on soldiers bound for France from the dockside at Portsmouth. The year promised a grandchild.

At the sanatorium outside Scarborough, where Brooke had been sent after his ordeal in the desert, Claire had often touched him, pulling his hands away from his wounded eyes, or rubbing liniment into his shattered knee, where his captors had put a bullet in the hope he’d have to die, slowly, in the sun, when they’d abandoned him south of Gaza.

He wanted to touch her now, but the bedpan was between them.

‘It’s an official call. I’m a detective inspector, Sister Brooke.’

He took off his hat, running a hand through the thick black hair, pushing it back off his forehead.

‘That means you get a free cup of tea.’

The sister’s desk was at the far end, with a view back down the serried ranks. This was Claire’s kingdom. She’d grown up the eldest child, with five younger brothers, and so her life often seemed like an endless, efficient attempt to bring order to chaos.

While she issued orders to a staff of three nurses, Brooke noted the disturbing anomaly that was silent children. A few ate their toast and drank tea, others lay still, a drip above one, another 31being spoon-fed. The soft, church-like hush was unnerving.

Brooke perched his hat on his knee; the injured knee, in fact, which had been rehabilitated through a rigorous programme of swimming initially administered by Claire in a pool at the sanatorium, the germ of his night-time summer passion.

He lit a cigarette. ‘Last night someone threw a child into the river in a sack. A boy, alive. The porter at Queens’ heard a cry as the body went past. We did our best, although I’m pretty certain it wasn’t good enough. I’ve had the sluices closed and we’re dredging the lower river. I’ve mentioned it downstairs, and apparently there was nothing suspicious overnight. Nothing here? Any recent admissions? Domestic bust-ups?’

Claire sat back, her blonde bobbed hair falling neatly into place. She had a round face crowded with large features, wide brown eyes and a generous mouth. Brooke doubted that any of the nurses had ever seen her discomposed.

‘One child brought in from a domestic in Romsey Town, that was the night before last. He’d been hit pretty hard, bruising and cracked bone here’ – she placed a finger on the bone ridge above the left eye. ‘He’s not going home until a constable calls at the house. We’ve seen the kid before. A regular customer, in fact.’

Brooke copied out an address and name.

‘Any more ideas?’ he asked, massaging his eyes. ‘I need to find a name.’

‘I’d try the obvious, Eden: orphanages, the council foster homes, the churches. Other than that, I think I’d just wait. Someone somewhere must be waking up to find a child gone. Just imagine if it was Joy.’

For a moment he saw his daughter as she’d once been: a child asleep in a cot, before he made the effort to push the image aside.32

Claire’s eyes moved up and down the ward. ‘It’s the usual dramas here.’ She pointed at the first bed on the right and onwards. ‘Meningitis, influenza, influenza … We’ve got nearly ten thousand evacuees in town, Eden. The vaccies are part of life. You know we’re on half-staff thanks to the war. It’s such a mess: when you break up families, everything’s up in the air. What do we do with a five-year-old who’s crying for his mum when she’s eighty miles away in the East End?’

Cambridge had become a city of children. Judged a safe distance from London, and largely bereft of heavy war industries, it was seen as an ideal sanctuary within a few hours’ journey of the capital. Crocodiles of youngsters, each child adorned with an evacuee’s label, were a common sight, weaving their way into town from the railway station.

‘Who’d do it, Claire – murder a child like that? What man would do that?’

‘Why’s it a man, Eden?’ she asked. ‘The world’s in chaos. The men are leaving for France, for basic training, for the navy, the air force. Families left in pieces. There’s plenty of women left who can’t cope. They don’t all have to suffer in silence.’ She wagged a finger. ‘Lesson number one, Inspector. Don’t make presumptions.’

CHAPTER FIVE

Detective Sergeant Ralph Edison appeared at Brooke’s office door at just after eight-thirty, armed, as always, with a mug of tea and a plate from the Spinning House canteen. The waft of fried bacon, several slices of which were compressed in a bap, had preceded him. The smell was poignant, as the imposition of pork rationing was days away and the hypnotic aroma might soon prove a thing of the past. Edison took a seat, the trouser legs of his old suit riding up to reveal clocks on his socks.

The outbreak of war had seen retired officers reassigned to active duty to fill the gaping holes left by conscripts and volunteers. Edison had been in the uniformed branch for thirty years, but Brooke needed a sergeant, and so the sixty-six-year-old had been forced to dust down that second-hand suit. Despite the plain clothes, Edison’s natural confident authority allowed him to 34project a sense of the old uniform, a kind of aura of constabulary power, even as it hung neatly in the wardrobe at home, shrouded in a paper cover.

‘Still no news from the river,’ said Edison, his voice unhurried, almost stately. ‘The only news will be bad news, of course.’

‘Yes. Indeed, Sergeant. But we need that body. We’ve nothing else. No name, no motive, no murder weapon – even the sack might give us a lead. The problem is: where is the body? Nooks and crannies, Edison. We need to look everywhere. It’ll turn up eventually. They always do. For now, we need to get on the killer’s trail. Today.’

Edison sipped his tea. Brooke often imagined that he could hear the mechanical workings of his sergeant’s steady mind, slow but sure. Retirement had promised him time for the allotment. Even now, in the dead of winter, he popped by on the way to the station. Judging by the earth on his hands he’d been wielding a spade, clearing snow perhaps from between the frozen beds of overwintered veg.

‘Domestics?’ asked Edison, finally.

Brooke pushed a piece of paper across the desk. ‘One. That’s a note of the name and address. The child’s in Addenbrooke’s with a cracked cheekbone. Claire says the father’s done it before. A constable’s down to visit – can you make sure it’s been done?’

Edison nodded.

‘I saw the child’s hand, Edison, as clear as you are.’

Edison nodded as if Brooke needed the affirmation.

‘So we’re saying a sack with a child – what, three, four years old?’ Edison held out his arm straight and curled his fist as if grasping the top of a sack. ‘He’s only stayed afloat because of the air in his lungs. He’s struggling, but he’s breathing, coming up for air – he managed to shout out. And there’s the 35cold water. He couldn’t have been in the river long, sir. My money’d be on Silver Street Bridge. That’s what, fifty yards upstream? Or the Little Bridges on Coe Fen – there’s three. Lonely, away from the main road.’

‘Check them out,’ said Brooke. ‘I sent young Collins to take a look at Silver Street last night. See if he saw anything. He’s on the second shift so he’ll be back in after lunch. The snow was thick, untouched. If that’s where the sack was hauled over there’ll have been tracks, prints.’

‘If he found anything, he’d have reported back,’ said Edison.

‘Maybe. Double-check. Meanwhile, let’s do the obvious, Sergeant. Schools, orphanages, council – anyone who deals with children. The boy’s missing. Let’s find his name.’ Brooke looked at his watch, standing. ‘Meanwhile, I’m for the top office.’

Within the Spinning House the euphemism ‘top office’ was universally recognised. Detective Chief Inspector Carnegie-Brown ruled the Borough with a blunt Glaswegian authority. Her eyrie, a large attic room, had housed, in the days of the workhouse, thirty fallen women in iron beds. She had brought to it an added spartan crispness.

‘Good luck, sir,’ said Edison, slipping away.

CHAPTER SIX

Chief Inspector Carnegie-Brown’s door was always open.

Brooke hovered, executing a nicely judged cough, noting that his superior was examining a file, glasses held at the bridge of a sharp nose. She sat behind a vast desk, complete with Highland hunting scenes carved in relief, which she’d had shipped down from her last post in Glasgow. Single, tweedy, aloof, she’d nevertheless gained some grudging respect for her straight dealing. Brooke had glimpsed her occasionally on his summer swims, camped out on a day off at Fen Ditton, fly fishing from the bank. She always conjured up a whiff of the Scottish great outdoors.

‘Brooke. Good – take a seat. The child – anything?’

Brooke filled her in, but he could tell she wasn’t listening, merely composing whatever it was she was going to say to 37him. They swapped some perfunctory remarks about calling on the county police force for reinforcements in the search. Then she pushed a file towards Brooke across the pristine surface of her desk.

‘You can read that at your leisure but let me offer a precis. Prince Henry, Duke of Gloucester, the king’s brother, who enjoyed a brief and unremarkable academic career at Trinity College, is to visit our fair city.’

Brooke was no cheering fan of the royal family. He’d been perfectly happy to fight for king and country, but he found the peripheral members of the dynasty he’d met on his duties remarkably unremarkable. In his head, he tried to reconstruct the current family tree. The old king had left five sons. The eldest – the disgraced Edward VIII – had abdicated to become the Duke of Windsor. That left George VI on the throne. Henry was the next oldest. Even then there were more: a younger Prince Richard, certainly; and one who’d died after the Great War, a sickly child, whose name escaped Brooke.

‘I know we don’t mention Windsor any more,’ said Carnegie-Brown. ‘With good reason. We don’t mention Henry either, for more benign reasons. A man of so little note his nickname is – apparently – the Unknown Soldier.’

Brooke nodded. He dimly remembered seeing a royal prince running in a steeplechase across Coe Fen, cheered on by a loyal crowd, on his return after the war. The city had been dour, grey and exhausted, like the rest of the country. So any occasion for celebration was seized on with a manic intensity. The spectators had hurrahed and waved flags; children perched on shoulders to get a princely view. He recalled a large, fleshy young man, tall but broad, with a round head, shyly raising a hand in response.38

‘Prince Henry is suddenly much more important than we thought,’ added Carnegie-Brown icily. ‘The king has two daughters, both yet to reach an age at which they could succeed their father fully, if there was an illness, an accident – or enemy action, God forbid. The family continues to stay in London, and the king wishes, on occasion, to visit the front line. If anything happened we’d need a regent. Henry has been chosen to fill this role. If anything happens he will, effectively, be king until the Princess Elizabeth comes of age. Then he’d go back to being a slightly less unknown soldier. Clearly this scenario is hypothetical. It is not theoretical. Measures have been taken. His personal security is of the utmost importance. If the king leaves the country – as he will do next week to visit France – then Henry is forbidden to do the same, despite his current military role as a liaison officer between our army on the Belgian border and Paris. Either King George or Prince Henry must be safely in the realm.’

There was something in Carnegie-Brown’s voice which intimated a less than unbridled affection for the institution it was her duty to defend. Brooke suspected a brooding Scottish grudge.

‘All of which amounts to a simple problem: we need to make sure his stay in the city is remembered for nothing more than its bland predictability. County is, in theory, coordinating the security, but in practice the burden of responsibility is ours. He’s on our ground.’

Outside of the old city centre, policing fell to the Cambridgeshire force. Its headquarters was less than half a mile away, on Castle Hill. Relations between the two forces were hostile, although no one Brooke had ever quizzed seemed able to trace this bristling antagonism back to any specific event. The prospect of liaison of any kind was not alluring.39

She tossed a note across the desk. ‘We can call on County for manpower, logistics. There’s a number there to call. Ring it, Brooke. Get all the help you can. Let’s get this over with and move on. The visit’s posted for Saturday 11th January. All leave is cancelled, here and at County.’

Dismissed, Brooke retreated to his office and read the file. The schedule for the royal visit was suitably mundane. Prince Henry planned to arrive by car, take up a suite of rooms at Trinity, then drive to a football match on Parker’s Piece between an army side and one raised by the university. He would then go back to Trinity, on foot, to take tea. In the evening he was to be the guest of Queens’ College. He would be invited to open the new Fisher Building, an extension on the west bank. There would be a celebratory formal dinner in the Great Hall. He would then return to Trinity to sleep, leaving by car after breakfast for St James’s Palace.

Brooke summoned his reserves of patience and stretched out his hand to pick up the phone and get a line to County, but the phone rang as he touched it. It was the duty sergeant from the front desk. A Father John Ward, of St Alban’s Church, Upper Town, had rung to say they had been sent thirty-two evacuees from London the day before. They had all been fed and slept in the church overnight. Roll call this morning revealed one was missing.

‘A five-year-old,’ said the duty sergeant, but Brooke was already on his feet, reaching for his hat, spurred on by the image of a pale hand breaking the surface of the silver and black river.