10,79 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: And Other Stories

- Kategorie: Fachliteratur

- Sprache: Englisch

What makes us who we are? Arno Geiger's father was never an easy man to know and when he developed Alzheimer's, Arno realised he was not going to ask for help. 'As my father can no longer cross the bridge into my world, I have to go over to his.' So Arno sets out on a journey to get to know him at last. Born in 1926 in the Austrian Alps, into a farming family who had an orchard, kept three cows, and made schnapps in the cellar, his father was conscripted into World War II as a 'schoolboy soldier' – an experience he rarely spoke about, though it marked him. Striking up a new friendship, Arno walks with him in the village and the landscape they both grew up in and listens to his words, which are often full of unexpected poetry.Through his intelligent, moving and often funny account, we begin to see that whatever happens in old age, a human being retains their past and their character. Translated into nearly 30 languages, The Old King in His Exile will offer solace and insight to anyone coping with a loved one's aging.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 200

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Ähnliche

Booksellers Love The Old King in His Exile

‘With humility and uncanny insight, Arno Geiger shines a pure and natural light upon a subject we too often shy away from, turning it into something very positive and uplifting. This book is a gift to all of us who struggle with life and death and all its jagged edges.’

Ray Mattinson, Blackwell, Oxford

‘A moving and revealing depiction of the reality of dementia. Told tenderly with love and respect, it is a celebration of humanity in difficult times and a testament to the importance of understanding one another.’

Claire Grint, Cogito Books, Hexham

‘A deeply affecting examination of the hope to be found amidst illness and loss. Geiger writes with clear eyes and an open heart.’

Marion Rankine, Foyles Charing Cross, London

‘Geiger writes about family, old age and illness with elegant poignancy and the kind of wisdom that only comes from painful experience, but there is strength and hope here too. This is writing that warms your heart even as it breaks it.’

Jenny Buckland, Heywood Hill bookshop, London

‘I loved everything about The Old King in His Exile and read it in one sitting. A really moving (both sad and joyous) treat.’

Richard Reynolds, Heffers Bookshop, Cambridge

‘A love letter from a son to his father, The Old King in His Exile completely avoids sentimentalism, yet is never lacking in humour and compassion. It made me realise that the sum of a life is the whole life and not just its ending.’

Claire Harris, Lutyens & Rubinstein, London

‘Arno Geiger invites us to share in precious time spent with his father and it feels like an honour to do so. Always honest about the brutal realities of dementia, Geiger nevertheless looks for the man and not the illness. With prose so beautifully simple yet striking it begs you to read passages aloud, I doubt there is anybody who could read this book and not be deeply moved.’

Danielle Culling, Mr B’s Emporium, Bath

‘This book is startlingly unsentimental, and yet a painful and touchingly realised picture of dementia, and the way it alters relationships between the sufferer and the people closest to them. It is incredibly relatable and emotionally provocative, but it also becomes a more general meditation on life and the continuous process of ageing.’

Lewis Wood, Topping & Co, St Andrew’s

First published in English translation in 2016 by And Other Storieswww.andotherstories.org

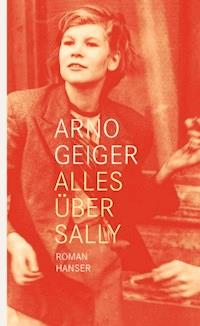

Copyright © Carl Hanser Verlag München, 2011 First published in German as Der alte König in seinem Exil in 2011 English-language translation copyright © Stefan Tobler 2017

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form without the prior written permission of the publisher. The right of Arno Geiger to be identified as author of this work has been asserted in accordance with Section 77 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

ISBN: 978-1-908276-88-9 eBook ISBN: 978-1-908276-89-6

Typesetting and eBook: Tetragon, London; Proofreader: Sarah Terry; Cover Design: Edward Bettison; Cover Illustration: Aurelia Lange.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

And Other Stories is supported by public funding from Arts Council England.

The translation of this work was supported by a grant from the Goethe-Institut, which is funded by the German Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and by the Austrian Federal Chancellery.

Contents

The Old King in His ExileAuthor and Translator BiographiesAnd Other Stories’ SubscribersCurrent and Upcoming BooksThe Old King in His Exile

You have to show what is most universal In a personal way.

HOKUSAI

When I was six, my grandfather stopped recognising me. He lived in the house down the hill from ours, and because I cut through his orchard on the way to school, occasionally he threw a piece of wood at me, saying I had no business on his land. Sometimes, though, he liked to see me and would come over, calling me Helmut. That didn’t mean anything to me either. My grandfather died. I forgot what had happened – until the illness started in my father.

In Russia there’s a saying that nothing in life returns except our mistakes. And that they become worse in our old age. As my father had always been somewhat eccentric, we told ourselves that the slip-ups he started to make after his retirement were because he allowed himself to lose interest in his surroundings. It seemed typical of him. So for years we nagged, urging him to pull himself together.

Now I’m seized by a silent rage at all that wasted effort, because we were scolding the person instead of the disease. ‘Please, don’t let yourself go!’ we said a hundred times, and our father put up with us patiently, as if believing things are easiest if you resign yourself to them in good time. He didn’t want to resist his forgetfulness and never used any memory aids. That way, he couldn’t mistakenly think someone else had put a knot in his handkerchief as a reminder. Nor did he fight tooth and nail against his mental decline, and he didn’t once try to broach the subject, although – with hindsight – he must have known it was serious by the mid-nineties at the latest. If he had said to one of his children, ‘I’m sorry, my brain is letting me down,’ everyone would have been able to deal with the situation better. As it was, for years there was a cat-and-mouse game where our father was a mouse, we were mice, and the disease was the cat.

That first nerve-wracking phase, marked by uncertainties and insecurities, is behind us. Although I still don’t like to think about it, I now understand that there’s a difference between giving up because you don’t want to try and giving up because you know you’re beaten. Our father accepted that he was beaten. Having arrived at that stage of life where his mental powers were on the wane, he staked everything on maintaining inner composure. Which, in the absence of effective medication, is also a practical solution for relatives who have to deal with this wretched illness.

In The Curtain, Milan Kundera writes: ‘Faced with the unavoidable defeat we call life, the only thing left to us is the attempt to understand it.’

I imagine dementia’s intermediate phase, the phase my father is in, more or less like this: you’re wrenched out of your sleep, you don’t know where you are, everything whirls around you – countries, years, people. You try to get your bearings, but you can’t. Everything continues to spin – the dead, the living, memories, dreamlike hallucinations, snatches of sentences that don’t mean anything to you – and this condition doesn’t change for the rest of the day.

*

When I’m back home in Wolfurt, as I am only occasionally, since a number of us share the burden of care, I wake my father around nine. He lies under his blanket, in shock, but he’s accustomed enough to people he doesn’t know stepping into his bedroom that he doesn’t complain.

‘Wouldn’t you like to get up?’ I ask him in a friendly voice. And to inject a little optimism, I add, ‘What a wonderful life we have.’

Sceptical, he struggles to his feet. ‘You, perhaps,’ he says.

I pass him his socks. He looks at the socks for a while with raised eyebrows and then asks, ‘Where’s the third one?’

I help him with dressing, to speed it up. He is willing to let me do it. Then I guide him down to the kitchen for breakfast. Afterwards I ask him to go and shave. He says, with a wink, ‘I’d have been better off staying at home. I won’t be visiting you again in a hurry.’

I show him the way to the toilet. He sings, ‘Oh dear, oh dear… oh dear, oh dear,’ playing for time.

‘If you shave, you’ll look sharp,’ I say.

He follows hesitantly. ‘If you say so,’ he murmurs. Looking in the mirror, he puts his hands on the hair sticking up on his head, pressing hard so that it actually stays down. He looks at himself again, declares, ‘Almost like new!’ and thanks me warmly with a smile.

He has started thanking me a lot. A few days ago, without any obvious reason, he said, ‘I thank you most kindly in advance.’

I respond encouragingly to such utterances now. ‘You’re welcome,’ I say, or ‘Don’t mention it,’ or ‘Happy to help.’ In my experience affirmative answers, which give my father the feeling that everything is fine, are better than the probing questions I used to ask, which only embarrassed and unsettled him. None of us like to answer questions that, if understood at all, only make us aware of our own inadequacies.

At first, the process of adjusting was painful and draining. Parents seem, to their children, strong and able to stand up to life’s unpleasant surprises, so we children are much harder on our parents for their increasingly visible weaknesses than we would be on other people. But over time I have settled into the new role pretty well. And I have learnt that you measure the life of someone affected by dementia differently.

If my father wants to say thank you, let him say thank you, even if there’s no obvious reason, and if he wants to complain, let him complain, whether or not his judgement is corroborated by the world of facts. He has no world beyond his dementia. As part of his family, I can only hope to remove some of the situation’s bitterness by allowing a sick man his muddled reality.

As my father can no longer cross the bridge into my world, I have to go over to his. There, within the limits of his own mental state, beyond the wider society based on objectivity and linear goals, he is still an impressive man, and although not always very sensible by common standards, somehow brilliant.

A cat wandered through the garden. My father remarked, ‘I used to have cats. Well, me and some other people. You could say I had a pawtial share.’

Once, when I asked him how he was, he answered, ‘No wonders, but signs.’

And then there were phrases plucked out of the blue, unreal as words from a dream: ‘Life doesn’t get any easier without problems.’

The wit and wisdom of August Geiger. The only shame is that language is slowly draining out of him, that breathtaking sentences are becoming rarer and rarer. To think what’s lost – that hurts. It’s as if I were watching my father bleed to death in slow motion. Life slowly seeps out of him, drop by drop. A person’s personality trickles out, drop by drop. It’s still intact, the feeling that this is my father, the man who helped bring me up. But the moments when I no longer recognise the father I once had are becoming more frequent, especially in the evenings.

Evening gives a taste of what mornings will soon bring, for with night comes fear. That is when, restless and helpless, my father wanders around like an old king in his exile. Everything he sees is frightening, everything sways, is unstable, threatens to dissolve in the next instant. And nothing feels like home.

I’ve been sitting for a while in the kitchen, typing up notes on my laptop. The television is on in the living room and my father, hearing voices coming from there, tiptoes across the floorboards, listens and murmurs to himself a number of times, ‘None of my business.’

He then comes into the kitchen and pretends to watch me as I write. But, glancing to the side, I notice he needs help.

‘Wouldn’t you like to watch some TV?’ I ask.

‘Why bother?’

‘Well, it would be fun.’

‘I’d rather go home.’

‘You are home.’

‘Where are we?’

I give his house number and the street.

‘All right, but I was never here much.’

‘You built the house in the late fifties and you’ve lived here ever since.’

He makes a face. He’s not satisfied with this information. He scratches his neck.

‘I believe you, conditionally. And now I want to go home.’

I look at him. Although he is trying to hide his confusion, you can see how difficult it is for him. He’s jumpy. Sweat glistens on his forehead. The sight of this man on the verge of panic shakes me.

His terrifying homeless feeling is a symptom of the illness. I can best explain it to myself like this: because of their inner disintegration, people with dementia no longer feel secure and so they long for a place where they will feel secure again. Yet since their confusion cannot be shaken off anywhere, however familiar the place, even in their own beds they aren’t at home.

To echo Marcel Proust: the true paradises are those we have lost. A change of location doesn’t help, except as a distraction, and singing serves that purpose just as well, if not better. Singing is more fun. People with dementia love to sing. Singing is emotional – a home outside the tangible world.

It’s often said that people with dementia are like small children. Almost all the writing on the subject makes use of the metaphor, which is annoying, because it’s impossible for an adult to regress to childhood, while it’s in a child’s nature to progress. A child develops new abilities; someone affected by dementia loses theirs. When you spend time with children, you gain a keen eye for every step forward; with dementia, for every loss. The truth is that age gives nothing back. It’s a helter-skelter downward slide and one of our greatest worries is that old age can last too long.

I turn the CD player on. My sister Helga bought a collection of classic folk songs for such occasions, such as ‘Hoch auf dem gelben Wagen’ and ‘Zogen einst fünf wilde Schwäne’. Often the trick works. We warble away for half an hour. He gets so wrapped up in the singing that I have to laugh. My father starts laughing, too, and as it happens to be time for bed, I seize the moment and steer him towards his bedroom. He is now in good spirits, although with no better sense of time, space, or what’s going on. At the moment that doesn’t bother him.

‘Not to win, but to endure is all,’ I think, and from this day on I’m at least as exhausted as my father. I tell him what he has to do, until he is wearing his pyjamas. He slips under the covers all by himself and says, ‘So long as I have a place to sleep.’

He looks around, lifts a hand, and greets someone whom only he can see. ‘It’s liveable,’ he comments. ‘Actually, it’s pretty nice.’

How are you, Dad?

Well, actually, I’m fine. But ‘fine’ in quotation marks, because I’m in no position to judge.

Do you ever think about the passing of time?

Time passing? I don’t actually mind whether it passes quickly or slowly. I’m not hard to please with these things.

The shadow of the onset still haunts me, although less intensely as the years go by. When I look out of the window onto the frosty orchard below and think about what happened to us, I’m overcome with the sense of a wrong step taken long ago.

Our father’s illness started in such a confusingly slow way that it was difficult to assign changes their true meanings. Things crept up on us, like Death in an old legend, hiding in the hallway and rattling his bones. We heard the noise and thought it was the wind in our ever-more-dilapidated house.

The earliest signs of the illness were there in the mid-nineties, but we didn’t manage to interpret them. Thinking back on the renovation work on the terrace flat, I can only shake my head bitterly: my father smashed to pieces the concrete covers of the disused septic tank, because he couldn’t lift them up and replace them over the opening. That was not the first time I believed he was making my life difficult on purpose. We shouted at each other. As the work continued, I often left the house fearing that when I returned, I’d be in for more nasty shocks.

Then there was the time a Swiss radio producer visited. That too is a day that has stuck in my memory. It was autumn 1997, shortly after my first novel had come out. He came to record a chapter that I would read aloud, so I asked my father not to make any noise that afternoon. Scarcely had the session begun before we heard a hammering from my father’s workshop, which lasted as long as the producer’s mic was on. Throughout my reading, I felt a deep anger towards my father – hatred, in fact, because of his lack of consideration. I avoided him for days, didn’t speak a word to him. The word on the tip of my tongue was ‘sabotage’.

And when did Peter, my older brother, get married? That was 1993. Our father got an upset stomach at the wedding reception, because he lost all sense of moderation and after the meal’s many courses devoured a dozen pieces of cake. Late that night he dragged himself home and had to spend a painful few days in bed. He was afraid of dying, but no one felt sorry for him because, as we thought, it was his own fault. No one noticed that he was gradually losing everyday skills.

The illness caught him in its net, gradually, subtly. Our father was already deeply entangled in it, without our noticing.

While we children were misinterpreting the signs, it must have been absolute torment for him to see himself change – and to fear that he was being taken over by something hostile, against which he couldn’t defend himself. He never commented on it. He wasn’t open enough to do that, nor able to share his emotions. It wasn’t in his character. It never had been and it was too late to change now. What made matters worse was that he had passed on to his children this lack of openness, which is why there was no real attempt from our side either. No one made the effort. We let things run their course. ‘Well, yes, he’s acting odd at times, but didn’t he always?’ This behaviour was actually normal for him.

*

At first, any peculiarities on his part really did look like the understandable effects of the new circumstances in which he found himself. He was ageing and his wife had left him after thirty years of marriage. It was easy to assume that this was the root of his apathy.

The separation had been tough on him. He had been dead set against divorce, partly because he wanted to stay with my mother, and partly because he believed some things were absolutely binding. He had not fully realised that certain conventions had become unable to bear the heavy loads they carried. In stark contrast to today’s flexibility about such things, my father held to a decision he had made decades ago and didn’t want to break his vows. In this respect he belonged to a different generation from his wife, who was fifteen years younger. For her, it was not her reputation or word that was at stake, but her life and the possibility of finding happiness elsewhere. My mother left their house, while my father clung inwardly to the dead relationship, faithful to what he had already lost.

As if something inside him had snapped, my mother’s departure led to a period of brooding and inaction. He even stopped looking after the garden, although he knew that his children were very busy with their jobs and struggled under the extra burden. He freed himself from practically all obligations. There was no trace of the enthusiasm with which he used to dive into projects. He announced that it was the young ones’ turn now – he’d already worked enough in his life.

We were annoyed by his excuses, and excuses they were, although for something other than what we suspected. We thought his failings were a result of doing nothing. But it was the other way around: the doing nothing was a result of his failings. As even small tasks were now too much for him, and as he knew he was losing control, he surrendered all responsibility.

Instead of watering the tomato plants every day, he spent his time playing patience and watching television. The monotony of his life revolted me. At a time when I was getting my career going, it seemed to me that dull indifference ruled his life. ‘Playing patience and watching television? That’s hardly enough for a life,’ I thought, and made no bones about my opinion. I pleaded with him, I teased and provoked him, I talked about inertia and the need for action. But even the most stubborn attempts to tear him out of his numbness failed dismally. With the look of a horse standing motionless in a storm, he would let my attacks wash over him. Then he’d go back to his routine.

If, back then, I hadn’t needed to work several months each year as a sound man at the Bregenz Festival, earning the money that writing didn’t bring my way, I would have avoided the family home. I only had to be back for a few days before a deep misery descended on me. It was the same for my siblings. Gradually everyone left home. We children scattered. Life got tougher for our father.

That was how we felt in the year 2000. Not only was the illness eating away at our father’s brain, it was also eating at the image that I had formed of him. Throughout my childhood and youth I had been proud to be his son. Now I was increasingly thinking of him as a halfwit.

Jacques Derrida was not wrong when he said that when you write, you are always asking for forgiveness.

*

Aunt Hedwig tells a story of a visit she and Emil – the eldest of my father’s six brothers – once paid him. Emil had brought hair clippers and a towel, although Aunt Hedwig no longer remembers whether my father let Emil cut his hair. It was mid-afternoon. To Aunt Hedwig’s surprise, there was a plate with leftover tomato sauce on the coffee table by the sofa. Later my father dropped a glass, and when he looked helplessly at it, Aunt Hedwig offered to clean up the shards. She asked him where he kept the dustpan and brush. He couldn’t recall. Looking at her, his eyes suddenly filled with tears. That was the moment when she knew.

They didn’t talk about it. Silently my father fought with himself. He didn’t attempt to explain anything. He didn’t attempt to escape – not until the pilgrimage to Lourdes.

That was in 1998, with Maria, the eldest of his three sisters, Erich, his youngest surviving brother, and Waltraud, his sister-in-law. My father, who hadn’t gone on a single holiday with his wife and children because – so he always said – he had seen the world during the war, now set off on a comparatively long journey with the faint hope of healing.

And then to stand there with an empty smile and pray at night and – as if the night prayers had no power – to do it again in the morning.

Maria, who by then was none too steady on her feet, apparently said to him, ‘You walk for me, and I’ll think for you.’

*

What we don’t understand terrifies us most. Which is why the situation improved for us once the signs accumulated that our father was affected by more than just forgetfulness and a lack of motivation. When everyday tasks presented him with insoluble problems, absent-mindedness could no longer be invoked as an excuse. It was impossible to keep fooling ourselves. Dressing himself in the morning, our father would only put on half his clothes, or put them on backwards or put on four sets. At lunch he would stick a frozen pizza, still in its plastic wrap, into the oven, and put his socks in the fridge. There came a time when we knew our father was affected by dementia and not just letting himself go – though we were slow to grasp the full extent of the horror.

For years the thought hadn’t even crossed my mind. My childhood image of my father blocked it out. As absurd as it sounds, dementia was the last thing I expected from him.

*