Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: SAMPI Books

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

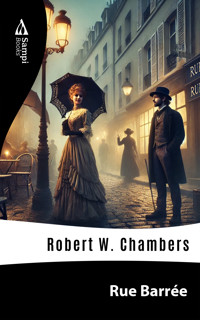

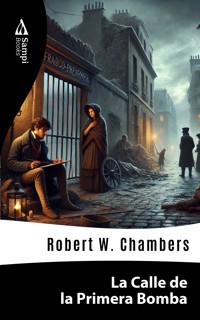

In "The Street of the First Shell" by Robert Chambers, the story is set in Paris during the Franco-Prussian War. It follows the lives of a group of struggling artists and their romantic entanglements amid the chaos of war. At its heart is the poignant relationship between an American artist, Jack Trent, and his love, Sylvia Elven. As they navigate the terror of bombardments and the emotional strain of wartime, the narrative explores themes of sacrifice, resilience, and the fragility of human connections.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 56

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

The Street of the First Shell

Robert W. Chambers

SYNOPSIS

In "The Street of the First Shell" by Robert Chambers, the story is set in Paris during the Franco-Prussian War. It follows the lives of a group of struggling artists and their romantic entanglements amid the chaos of war. At its heart is the poignant relationship between an American artist, Jack Trent, and his love, Sylvia Elven. As they navigate the terror of bombardments and the emotional strain of wartime, the narrative explores themes of sacrifice, resilience, and the fragility of human connections.

Keywords

War, artistic, resilience.

NOTICE

This text is a work in the public domain and reflects the norms, values and perspectives of its time. Some readers may find parts of this content offensive or disturbing, given the evolution in social norms and in our collective understanding of issues of equality, human rights and mutual respect. We ask readers to approach this material with an understanding of the historical era in which it was written, recognizing that it may contain language, ideas or descriptions that are incompatible with today's ethical and moral standards.

Names from foreign languages will be preserved in their original form, with no translation.

I

"Be of Good Cheer, the Sullen Month will die,And a young Moon requite us by and by: Look how the Old one, meager, bent, and wan With age and Fast, is fainting from the sky."

The room was already dark. The high roofs opposite cut off what little remained of the December daylight. The girl drew her chair nearer the window, and choosing a large needle, threaded it, knotting the thread over her fingers. Then she smoothed the baby garment across her knees, and bending, bit off the thread and drew the smaller needle from where it rested in the hem. When she had brushed away the stray threads and bits of lace, she laid it again over her knees caressingly. Then she slipped the threaded needle from her corsage and passed it through a button, but as the button spun down the thread, her hand faltered, the thread snapped, and the button rolled across the floor. She raised her head. Her eyes were fixed on a strip of waning light above the chimneys. From somewhere in the city came sounds like the distant beating of drums, and beyond, far beyond, a vague muttering, now growing, swelling, rumbling in the distance like the pounding of surf upon the rocks, now like the surf again, receding, growling, menacing. The cold had become intense, a bitter piercing cold which strained and snapped at joist and beam and turned the slush of yesterday to flint. From the street below every sound broke sharp and metallic—the clatter of sabots, the rattle of shutters or the rare sound of a human voice. The air was heavy, weighted with the black cold as with a pall. To breathe was painful, to move an effort.

In the desolate sky there was something that wearied, in the brooding clouds, something that saddened. It penetrated the freezing city cut by the freezing river, the splendid city with its towers and domes, its quays and bridges and its thousand spires. It entered the squares, it seized the avenues and the palaces, stole across bridges and crept among the narrow streets of the Latin Quarter, gray under the gray of the December sky. Sadness, utter sadness. A fine icy sleet was falling, powdering the pavement with a tiny crystalline dust. It sifted against the windowpanes and drifted in heaps along the sill. The light at the window had nearly failed, and the girl bent low over her work. Presently she raised her head, brushing the curls from her eyes.

"Jack?"

"Dearest?"

"Don't forget to clean your palette."

He said, "All right," and picking up the palette, sat down upon the floor in front of the stove. His head and shoulders were in the shadow, but the firelight fell across his knees and glimmered red on the blade of the palette-knife. Full in the firelight beside him stood a color-box. On the lid was carved,

J. TRENT.École des Beaux Arts.1870

This inscription was ornamented with an American and a French flag.

The sleet blew against the windowpanes, covering them with stars and diamonds, then, melting from the warmer air within, ran down and froze again in fern-like traceries.

A dog whined and the patter of small paws sounded on the zinc behind the stove.

"Jack, dear, do you think Hercules is hungry?"

The patter of paws was redoubled behind the stove.

"He's whining," she continued nervously, "and if it isn't because he's hungry it is because—"

Her voice faltered. A loud humming filled the air, the windows vibrated.

"Oh, Jack," she cried, "another—" but her voice was drowned in the scream of a shell tearing through the clouds overhead.

"That is the nearest yet," she murmured.

"Oh, no," he answered cheerfully, "it probably fell way over by Montmartre," and as she did not answer, he said again with exaggerated unconcern, "They wouldn't take the trouble to fire at the Latin Quarter; anyway they haven't a battery that can hurt it."

After a while she spoke up brightly: "Jack, dear, when are you going to take me to see Monsieur West's statues?"

"I will bet," he said, throwing down his palette and walking over to the window beside her, "that Colette has been here to-day."

"Why?" she asked, opening her eyes very wide. Then, "Oh, it's too bad!—really, men are tiresome when they think they know everything! And I warn you that if Monsieur West is vain enough to imagine that Colette—"

From the north another shell came whistling and quavering through the sky, passing above them with long-drawn screech which left the windows singing.

"That," he blurted out, "was too near for comfort."

They were silent for a while, then he spoke again gaily: "Go on, Sylvia, and wither poor West;" but she only sighed, "Oh, dear, I can never seem to get used to the shells."

He sat down on the arm of the chair beside her.

Her scissors fell jingling to the floor; she tossed the unfinished frock after them, and putting both arms about his neck drew him down into her lap.

"Don't go out to-night, Jack."

He kissed her uplifted face; "You know I must; don't make it hard for me."

"But when I hear the shells and—and know you are out in the city—"

"But they all fall in Montmartre—"

"They may all fall in the Beaux Arts; you said yourself that two struck the Quai d'Orsay—"

"Mere accident—"

"Jack, have pity on me! Take me with you!"

"And who will there be to get dinner?"

She rose and flung herself on the bed.

"Oh, I can't get used to it, and I know you must go, but I beg you not to be late to dinner. If you knew what I suffer! I—I—cannot help it, and you must be patient with me, dear."

He said, "It is as safe there as it is in our own house."