9,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The O'Brien Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

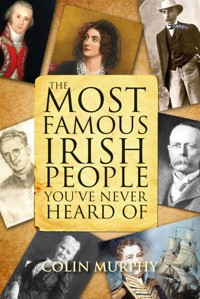

Did an Irish monk discover America? Which rebel died of having a feckin' tooth pulled? And who in the name of Jaysus was responsible for the Pledge? If you've ever wondered how much of our rabble-rousing history is true, and how much a load of wojus oul' bull, then look no further. From the great to the gormless, this book is a hilarious parade of the life stories of Ireland's favourite heroes and gougers. Gathered in a collection of the best anecdotes from our chequered past, it will tell you everything you need to know about our writers, revolutionaries, and rogues. You never know - it might help you win the odd pub quiz as well... The Feckin' collection returns with a funny, original and quirky take on some of Ireland's most famous faces! Illustrated with photographs and cartoons, the book covers key Irish figures across the millenia like: - William Butler Yeats - Nobel Prize winning poet - Saint Patrick - Patron Saint of Ireland - Sir Ernest Shacklton - legendary Antarctic explorer - Jonathan Swift - the man who wrote Gulliver's Travels - Grace O'Mally - the pirate queen who ran Queen Elizabeth's troups ragged - Brian Boru - the last High King of Ireland And many more!

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Ähnliche

Contents

Cormac Mac Airt

(third century)

Like Michael Jackson, bits of Cormac are real and other bits were added on to improve his image. The real bits are that he was a High King of Ireland, and a very good one at that, and the unreal bits are the legends associated with him, stuff about magical cups and wolves raising him and other malarkey.

It all started for Cormac when his grandfather, Connaughtman Olc Acha, decided to get on (High King) Art Mac Cuinn’s good side. So over a few tankards of ale he gave the king his daughter, Achtan – being High King could have its advantages. No sooner was she preggers with Cormac than she had a dream involving her head being chopped off, a tree sprouting from her neck and then another tree sprouting from the first tree, which would be washed away by the sea. This was interpreted as meaning that Cormac would be High King, that the sea would somehow kill him and that Art would die in battle. Well, what other way could you look at it? Sure enough the randy oul’ king was chopped down by Lugaid Mac Con the next day, and he now became High King.

Legend takes over for a while and, in a tale strangely reminiscent of ancient Rome, Cormac is stolen by a she-wolf when he’s a snapper and raised, Romulus and Remus-like, by wolves in a forest. But eventually a hunter finds him, takes the young lad back to his Mammy and he grows up to be a wise, merciful and handsome hunk, a fine catch for any Iron Age wench.

The next bit is probably part legend, part real. When he was 30, Cormac went to Tara, the seat of the High King, Lugaid, the guy who’d killed his father. Ancient texts describe his looks at this point:

‘His hair was curled and golden. He stood in the full glow of beauty, without defect or blemish. You would think it was a shower of pearls that were set in his mouth; his symmetrical body was as white as snow; his eyes were like the sloe; his brows and eyelashes were like the sheen of a blue-black lance.’

Or in modern Irish parlance, he was a bleedin’ ride.

At Tara, he made a judgement in a case involving a woman’s sheep, which had been confiscated by the High King because they’d ‘eaten the queen’s woad’. Painful as this sounds for the queen, woad was just a plant and Cormac decided that because the woad would grow back, as would the sheep’s fleece, the woman should merely have lost her sheep’s fleece, not the entire flock. The people applauded the wisdom of this so much that they gave Lugaid the boot.

Unfortunately the throne was then seized by another head-the-ball called Fergus Dubdétach, who drove Cormac back to Connaught. So Cormac made an alliance with a fearsome brute called Tadg Mac Céin, who marched against Fergus. Tadg and his men chopped off Fergus’s brother’s head. Wrong head. Then they chopped off Fergus’s other brother’s head. Wrong head again. Finally they chopped off the right head.

As a reward, Cormac told Tadg that he could have any land that he could encircle in a day; he must have been a hell of a charioteer, because he got half of northern Ireland.

Finally Cormac was High King, and his Mammy’s vision had been fulfilled. He married Eithne, who bore him 13 kids. Then, with Eithne no doubt banjaxed from all that child-bearing/rearing, he took a mistress called Ciarnait. Eithne, was pretty miffed, as you can imagine, so she forced Ciarnait to slave over a grindstone. Cormac is said to have built Ireland’s first watermill to save her from this chore.

When not bedding Eithne or Ciarnait, Cormac battered the crap out of any rival kings. He clattered Connaught and Munster into submission and is said to have conquered parts of Britain, which makes a nice change. His reign reputedly lasted for over 30 years during which he turned Tara into a fabulous palace and seat of learning, according to the ancient Irish annals. Cormac also had a book compiled, the Psalter of Tara, which chronicled all of Irish history and the ancient Brehon Laws, which would remain in use until the English arrived seven centuries later and screwed everything up. Unfortunately the Psalter of Tara has been lost, but there might be one preserved in a bog somewhere and if you happen to find it, it’s probably worth a few bob.

Poor Cormac was stuffing his gob with a salmon one night when he choked on a bone – fulfilling his Mammy’s vision of his death by the sea somehow claiming him. Well, sort of.

Cormac was regarded as the greatest of all Irish kings. And the ancient texts say of him that he ‘reigned majestically and magnificently’. Wonder what future texts will say about our most recent bunch of leaders/gougers?

Niall of the Nine Hostages

(died 405)

He may be part fact, part fiction, part mythology, but one thing we say for certain is that Niall was definitely all man. In his time he kicked the arses of all the other Irish kings, terrorised the bejaysus out of the Brits, battered the merde out of the French and even had a go at the Roman Empire. He also bedded half the cailíns in Ireland, and his sexual prowess is something we can prove scientifically.

Based on the written records, which come from documents composed long after he’d bitten the bog, Niall was said to be a descendant of a dude called Conn of the Hundred Battles, so it seems hacking people to bits was in his blood. He hailed from the Donegal/Derry area and lived around the late fourth century. His father was Eochaid Mugmedón, High King of Ireland, who had five sons by two wives, polygamy being the order of the day. Wife 1, Mongfind, gave him four sons and Wife 2, Cairenn Chasdub, gave him Niall (Jaysus – Eochaid, Mugmedón, Mongfind and Chasdub. What is this? Dickens?). It seems that when Mongfind fell out of favour – and out of bed – with the king, she grew jealous of her successor, the now-pregnant Cairenn, and so the oul’ bat made her do all the heavy work.

So one day poor Cairenn drops her sprog, and terrified of Mongfind, abandons the little mite. Luckily Niall is discovered by a poet called Torna, who raises him, and when he grows up, he returns to Tara and batters a few heads, freeing his mother from her toils. Naturally, Mongfind is seriously freaked out, so she nags Eochaid to name one of her sons as his successor. But the wise king devises various tests to choose who will plonk his arse on the throne. During one of these expeditions, the thirsty lads find a well guarded by an old hag with a face like a full skip. To drink at the well they must first kiss her. Only Niall will give the ugly old crone a proper seeing to, after which she magically turns into Miss Universe 378, and not only gives Niall a drink, but the kingdom, and the guarantee that 26 of his descendants will also be king. This bit about an ugly oul’ bag magically turning into a beautiful woman before a drink, suggests this is pure mythology, as making a horrible wagon appear gorgeous can usually only be achieved after drinking 20 pints.

Anyhow, after his Da died, Niall was proclaimed High King, and kindly gave smaller kingdoms to his big brothers – Connaught for you, Munster for you etc. But they weren’t all happy with their lot and before you could disembowel a druid, they were at each other’s throats. Niall prevailed, but didn’t overcome the powerful Énnae Cennsalach, King of Leinster, and his son Eochaid.

Eochaid, it seems, had been refused hospitality by Niall’s chief poet Laidceann. This was the height of bad manners apparently and reason enough to hack a few thousand men to pieces. After a few more bloody encounters (in which Eochaid impressively killed Laidceann by throwing a stone at him, burying it in his head), Niall exiled Eochaid to Scotland.

Niall then went off pillaging and raping, terrorising the poor Brits and taking countless slaves, among whom was reputed to be St. Patrick. He then invaded France, and in one version, battled all the way to the Alps where he attacked Roman legions, causing the Emperor to send an ambassador to make peace. It is more likely that Niall’s encounters with Romans in Briton were the source of this, and some gobshite mixed up the names ‘Alba’ (Britain) and ‘Elpa’ (Alps).

By now Niall had become numero uno in Ireland, Scotland, Britain and northern France. As the tradition was to hand over a hostage to the victorious king to ensure subservience, he got one each from Ulster, Leinster, Connaught, Munster and Meath, the Picts in Scotland, the Saxons, the Britons and the French. And if you haven’t figured it out yet, ergo his trendy nickname.

Niall’s reign inevitably came to a bloody end, and it is generally accepted that he was killed by Eochaid (remember the guy exiled to Scotland?). The most popular account had Niall presiding over an assembly of Picts, when Eochaid, who as we know had a fierce strong arm, shot an arrow across a Scottish valley and felled the great king, who was brought home and buried at Faughan Hill near Navan.

Niall’s principal legacy was as founder of the powerful O’Neill dynasty, which would endure for hundreds of years. Oh, and then there’s his offspring. Legend officially records him as having two wives, about 12 sons and an unknown number of daughters. Of course any young lass would gladly fall into the king’s arms and bear his child, and it seems Niall’s arms were so perpetually full of young slappers it’s a wonder he ever had time to pull on his goatskin knickers and chop someone’s head off. How do we know this? Well, a number of years ago a team of geneticists from Trinity College, Dublin, analysed the genes of gazillions of Irish folk, and of those of the diaspora, and announced that 20% of men in the north west had an ancient common male ancestor from the time of Niall’s reign. They further estimated that there are three million men alive today with a bit of Niall in them, something those ancient cailíns would have also experienced. Startlingly, one in fifty New Yorkers of European descent are also descended from Niall. So whatever else, he certainly had steel in his sword.

A fascinating footnote to this is the tale of Harvard Professor, Henry Gates Junior, who in Massachusetts in 2009, returned home, found himself locked out and tried to break in. A cop, Sgt. James Crowley, duly arrested Henry, who is African American, and a huge row erupted when Henry accused Crowley of racism. It got such press that President Obama stepped in and settled the matter over a beer in The White House. What the feck does this have to do with Niall of the Nine Hostages? Well, it seems that while making up, the Professor and Sgt. Crowley discovered that they both carried the gene identified by the Trinity College scientists – they were both the beneficiaries of Niall’s ancient bed-hopping.

St. Patrick

(c. 387–461/2)

You’ve probably heard of this guy already, and if you haven’t, welcome to Earth. In case you’re from Seti Alpha Six, he’s Ireland’s patron saint, along with St. Columba and St. Brigid. We’re all familiar with the plastic green version of him, but what’s the story with the real dude? Or was there ever really some head-the-ball going around saving us Paddies from eternal damnation and chasing away snakes etc? To give an appropriately Irish answer: yeah no.

There probably was a St. Patrick, although we don’t know much about him, and what we do know mostly comes from his own ‘Confessio’, which he wrote when he was old and wrinkly and in which he isn’t shy about telling us the wonderful job he’d done ridding us of nasty pagans. In his account, God spoke to him so often that it seems like he had God’s personal mobile number. Unfortunately there was another holy geezer knocking about at the time called Palladius, also referred to as Patrick (from the Latin ‘patricius’, which means ‘revered one’ or something). The Pope sent Palladius as Ireland’s first official bishop. Somewhere in the fog of history, bits of Patrick got mixed up with bits of Palladius, and nobody knows whose bits are whose.

Here’s the basics. St. Paddy was probably born around 387 at a place called Bannavem Tiburniae in either Cumbria, England, or Kilpatrick, Scotland, or Pembrokeshire, Wales, or even Brittany, France. His name was Maewyn Succat, and thanks be to Jaysus he changed that, because ‘The St. Maewyn Succat’s Day Parade’ just doesn’t have the same ring about it. His Da was a pretty well-off Roman (and a Christian), called Calpurnius, and his Ma was probably called Conchessa. But here’s the thing – young Maewyn didn’t believe in God!

When he was 16 a bunch of Irish pirates whisked him away into slavery in Antrim. Slemish Hill makes claim as the place where he spent six years minding sheep, although according to some he was offloaded somewhere around Mayo. His boss was a pagan gouger called Milchu. Luckily around this time, God set up his direct line to Paddy, and ‘had mercy on my youthful ignorance’, forgiving him his sins, presumably like impure thoughts about slave girls and binge-drinking mead. Being a very organised sort, God also arranged a ship to take him to freedom – if he could escape, walk 200 miles to the port and persuade the captain to give him a lift. Pity God couldn’t have organised somewhere a bit closer, but then, God works in mysterious ways.

Anyway, the ship landed maybe in Britain or maybe Brittany, and Paddy and the pagan crew wandered around starving for a month, before our future saint prayed to God and a herd of unfortunate boar miraculously appeared. After they’d been hacked up and digested, the crew declared Paddy’s God the real deal, and he was a hero.

Eventually he returned home and got stuck into his Da’s bible so he could become a properly qualified Christian. Then he had another vision in which a man called Victoricus brought him a gansey-load of letters, all begging him to return to Ireland – ‘Oh holy boy, come walk again among us’. You could say that this defined his career path.

So back to Ireland he goes, like a returning emigrant but without the irritating Aussie/American twang. This was about 431, and before you know it he’s baptising babies, ordaining priests and persuading everyone to renounce depraved pagan practices, and become chaste, honest, moral Christians, like we’ve been ever since (ha ha). He also convinced lots of women to become ‘virgins of Christ’, much to their boyfriends’ annoyance.

Eventually made a bishop, Patrick refused to accept gifts from kings, really pissing them off as these were just bribes. Neither would he accept payments for baptisms, ordinations or even from his virgins, who used to ‘throw their ornaments on the altar’, like the way women throw their knickers at Tom Jones. At one point he was accused of something by someone and put on trial, perhaps for ‘financial irregularities’ (maybe he had a secret bank account in the Cayman Islands, like most rich Irish people). Presumably he was found innocent, as he wrote all about it in his ‘Confessio’.

Paddy acquired a few legends along the way concerning shamrock and snakes. He’s said to have used the shamrock to explain the mystery of the Holy Trinity – how the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit were the one God. This is celebrated every year with the use of inflatable plastic shamrocks made in China. He also reputedly drove the snakes from Ireland – a pretty easy task as there were no snakes in post-glacial Ireland. Of course, the snake was a Druidic symbol, so the legend probably refers to ridding us of that shower of savages.

When exactly he went to his heavenly reward is a bit murky. It was possibly 457, but that might be when Palladius kicked the bucket. Alternatively it was in 461/2. But one source claims he cashed in his chips on March 17th, 492, aged 120. Maybe all that wandering Ireland’s bogs kept him fit.

After he died there was almost war between the Ui Néill and Ulaid clans, who both wanted his body. You can just imagine the Ui Néills at one end pulling his arms and the Ulaids at the other yanking his legs. But legend has it that he was finally buried in Down Cathedral, and you can still visit his grave, although it may only contain the half of him that the Ui Néills got.

That’s pretty much it. There isn’t much more known about St. Paddy, except that he’s given us all an excuse to get rat-arsed once a year. One suspects he wouldn’t be deliriously happy about that legacy.

St. Brigid

(c. 451–523)

Another of Ireland’s patron saints, although there’s no day off to get trollied in her honour. She’s also called Bridget, Bridgit or Bride meaning ‘exalted one’. There was a pagan goddess, also called Brigid, who also supposedly possessed healing powers, like our Brigid, and St. Brigid’s feast day, February 1st, also happens to be the date of the Imbolg, the pagan Spring festival.

Her father was a pagan guy called Dubhthach, a king in Leinster, and her mother was Brocca, a slave. In other versions, her father was also a slave kidnapped by Irish pirates from warm, sunny Lusitania (Portugal) and hauled back to wet and windy Ireland. After her birth, probably in Louth, a druid told her father to call her after the pagan goddess, and then tried to feed her. However she puked all over the nasty pagan, which was taken as a sign of his impurity (i.e. he wasn’t a Christian) but which was probably a case of gastroenteritis caused by eating undercooked pig’s eye or something.

As she grew up, Brigid started healing people left, right and centre. She was also a beauty and lads were soon blowing wolf-whistles and generally making a nuisance of themselves. But Brigid had promised herself to God, so the lads were rightly miffed. And it wasn’t beyond her to cast the odd curse. One poor eejit called Bacene, who made fun of her for remaining a virgin was cursed so: ‘Your eyes will burst in your head’. Two exploding eyes later, Bacene got the message.

Brigid was renowned for her charity and kept giving away her parents’ stuff to the poor. This reached a climax when she gave her father’s jewel-encrusted sword to a leper. Dubhthach was like a mad thing and finally granted her wish, packing her off to a convent. Clever girl.

She was ordained a nun soon after and given abbatial powers, which was a big deal as she was only 17. Off she went on her travels, convincing lots of young girls to become nuns. She founded a small oratory in Kildare that eventually became a major centre for pilgrimage and learning, two monastic institutions, one for the boys, one for the girls, and also an art school, which produced a Book of Kells-type masterpiece, called the Book of Kildare, which was lost, but which was said to be ‘a work of angelic skill’.

Biddy was a busy nun. Her monasteries and schools became famed throughout Europe and soon there were all sorts of head-the-balls turning up with funny accents. She actually became best buddies with Mr Big of the Irish monastic world, St. Paddy – it was said of ‘there was so great a friendship of charity that they had but one heart and mind.’

Among Brigid’s top miracle hits were curing a leper with a mug of blessed water, and curing two deaf sisters by rubbing some of their blood mixed with water on their necks. She could also multiply foods and control the weather. Handy tricks to have up your abbess’s sleeve.

Her most famous miracle is the one with the cloak. She wanted a local king to donate land for a convent, but the mean oul’ shite refused. So after a word with God, she tried again, asking the king for ‘as much land as my cloak will cover.’ Of course the sucker agreed. So four co-nuns grabbed a corner of the cloak each and started walking in different directions, and the cloak magically stretched out to cover the size of a football pitch. The king converted and the convent was built.

Then there’s the St. Brigid’s Cross. You know the one with the square middle bit and four arms radiating out? A pagan chieftain was dying and Brigid arrived to convert him before he ended up in hell. But he wasn’t having any of it and was ranting and raving. So she started absent-mindedly weaving the rushes on the floor together and made a cross, and miraculously, the chieftain became transfixed by this and converted in the nick of time, saving himself from eternal roasting.

As a thank you for all the good PR, God spared her till she was 72, an impressive age at the time. She was originally buried, it is said, alongside St. Patrick and St. Columba in Downpatrick Cathedral, in Down, but a few centuries later some knights removed her skull (yeuch) and gave it as a gift to King Denis of Portugal. Perhaps he’d have preferred a nice jumper or a box of chocolates, but there you go. The skull is today in a fancy metal box in the Church of John the Baptist in Lisbon. Brigid also has a gazillion places around Ireland named after her – there are 19 Kilbrides alone (‘Kil’ meaning ‘church’), as well as places like Brideswell, Rathbride, Templebreedy. And she’s an international hit too, having had artworks, churches etc. named in her honour in Scotland, France, England, Belgium, Germany, Italy, Holland, Portugal, Spain and the USA.

And all this despite never having been officially canonised. You see, she became a saint because so many people revered her that the Vatican thought ‘Oh what the hell,’ and officially recognised her. The slave girl from Louth did well for herself.

St. Brendan the Navigator/the Voyager

(c. 484–c. 577)

Did an Irishman discover the Americas a millennium before Columbus? Who knows? There’s a possibility that St. Brendan did. Of course, this ‘discovering America’ bullshit ignores the fact that there were already indigenous people living there for yonks. But we digress.

St. Brendan was a real guy, a Kerryman, born around 484, to the joy of parents Finnlug and Cara. Originally they’d planned to name him ‘Mobhí’, but changed their minds due to portents in the sky or some malarkey, so called him ‘Broen Finn’, meaning ‘Fair Drop’, as in ‘Jaysus, I’ve had a fair drop and I’m rat arsed’. No, only kidding. It probably meant he was fair-haired. He was baptised by a holy oul’ lad called St. Erc, educated by a holy oul’ wan called St. Ita and then by another holy guy called St. Jarlath, so it was perhaps inevitable he’d end up a holy Joe himself. Incidentally, St. Ita was said to embody the ‘six virtues of womanhood’ – wisdom, purity, musical ability, gentle speech and needle skills. Well, at least Irish girls still have the wisdom.

Besides the call of God, he also heard the call of the sea, and before you could say a Hail Mary, he was off sailing around Ireland, converting pagans and founding monasteries all over the gaff. Not content with saving the souls of Paddy pagans, he also journeyed to Wales, Scotland and Brittany. Clearly the travel bug had bitten.

At some point in his thirties or forties, Brendan decided to sail into the vast sea to the west. This is where fact and fiction become somewhat intertwined, or to put it another way, banjaxed. Most of the legend of Brendan’s voyage was written centuries after he died, and it has to be taken with a container ship of sea salt. There are elements of Irish mythology in it, not to mention Greek mythology and various other mythologies.

Brendan set off from the foot of Mount Brandon (hence its name) with a number of followers, either 12, 14, 60 or 150, depending on who you believe. His boat was made of wattle (bits of sticks tied together) covered in hides. On their adventure they encounter a land where ‘demons throw down lumps of fiery slag from an island with rivers of gold fire [and] great crystal pillars’. Some say this is a description of Iceland. Fair enough. They also find an island where food has been left out for them, but mysteriously, there are no people only an Ethiopian Devil, whatever the hell that is. But now it gets a bit freaky, because next up is the Paradise of Birds inhabited by birds, who, wait for it, recite psalms to the Lord. Talking birds? Ok, let’s move on.

Along comes the island of Ailbe, inhabited by ageless silent monks. After spending Christmas here and having a bit of turkey and pud, the voyagers depart. They have various other adventures with sea creatures, birds bringing prophesies and an island of blacksmiths (yes, that’s right, blacksmiths, for the love of Jaysus). On one small island, they light a fire only to discover the ‘island’ is actually a whale. You’d think the eejits would notice that the ground was a bit smooth and rubbery, but no. Then along comes a ‘gryphon’, like the ‘griffin’ of Greek mythology – half lion and half eagle. Anyway, it’s about to devour them when another fabulous bird bates the shite out of it. Next, they find Judas sitting on a rock in the middle of nowhere. It seems he gets a day off from Hell on Sunday and gets to spend it here – we all need a break every now and then.

Among the most fabulous places they discover was one they called St. Brendan’s Island – a beautiful place covered with luxuriant vegetation. In the centuries before Columbus, the legend of Brendan’s Voyage had become so widespread across Europe that this mysterious island was actually marked on maps and there were reported sightings of it up to the 19th century. It may have been the Faroes, Canaries, Madeira, the Azores or it could all be a big pile of baloney. On the other hand, as some maintain, it could also have been America. The absence in America of an ancient sign reading ‘St. Brendan was here. You’ll never beat the Irish!’ makes this theory tricky to prove. Still, if you ignore the sea creatures, blacksmiths, immortal monks, gryphons, etc., it may just be possible that old Brenno beat Columbus to the line by 1000 years. In the 1970s, an English chap by the name of Tim Severin built a reconstruction of Brendan’s boat, and managed to reach America in it to show the voyage was possible. Fair play to you, Tim.

Back from his fab voyage, normal service was resumed and Brendan founded loads more monasteries, most famously at Clonfert in Galway and Ardfert in Kerry. Brendan’s final voyage was a visit to his sis, Briga, in Galway, where he died. Apparently, fearing that the peasantry would try to nab bits of him as keepsakes, he’d asked to be quickly laid to rest in Clonfert, before his leg, ear or some other unspeakable part of him ended up on someone’s mantelpiece. So his corpse was secretly whisked away and buried beside the church. There’s a headstone at Clonfert Cathedral claiming to be his grave. Yeah, right.

There’s no doubt Brendan existed, that he sailed a lot and that he established lots of monasteries and so on, and he is officially recognised as a saint by the Catholic, Anglican and Eastern Orthodox Church. And he may even have discovered America. If he did, he deserves a big slap on the back. It would be fitting, wouldn’t it, considering we’ve sent about a billion other people there since.

There’s a whole heap of stuff named after or written about Brendan. Mountains, churches, songs, poems, films, documentaries, books, you name it. There’s even a rock song by a Canadian band, The Lowest of the Low, called ‘St. Brendan’s Way’. It appears on an album called Shakespeare My Butt. Brendan’s also the patron saint of sailors, and of scuba divers. Perhaps he should also be the patron saint of emigrants?

Ivar the Boneless

(died c. 873)

Strictly speaking, the intriguingly named Viking may not even have been born here, but his name is worth a laugh, so let’s make him an honorary Paddy.

Ivar ruled over the Uí Ímair Viking dynasty, which existed from the mid-ninth to the late tenth century, which meant he had lots of Britons under his thumb, so he can’t have been all bad. His kingdom was one of the most powerful in the Viking world, stretching from the Hebrides, through Scotland, across Northern England, Wales, the Isle of Man and Ireland. It was said of Ivar that he was ‘fair, strong, wise and a great warrior’, and as he made his conquests the local gentry would gift him their daughters to appease him, one of whom was called Aud the Deepminded. The Boneless and the Deepminded? So what was their unlucky firstborn known as – ‘the Boneminded’?

Besides his gold-plundering, virgin-stealing, all-conquering adventures, the most intriguing thing about Ivar has to be his name, which has been a matter of some speculation. One of the most curious suggestions is that, in the baby-making department, poor Ivar was about as erect as a length of over-cooked linguini. This is unlikely, however, as he had several wives and was frequently required to ravish a wench or two to prove his leadership skills. Another theory is that Ivar was incredibly flexible in battle, and could slice the kidneys out of one opponent while at the same time castrating a second guy behind him. A further theory is that his name was screwed up in translation and it actually means ‘Ivan the Legless.’ This is much more plausible, as anyone who’s ever spent any time in Dublin any weekend can confirm. Taken literally, though, it may imply that poor Ivar had no legs, and there’s evidence that he was borne on his shield by his warriors. But then Vikings usually carried their glorious warriors about on their shields, so unless we assume that every Viking king had no legs, it is unlikely this explains the nickname. And it is a bit hard to imagine Ivar being ‘a great warrior’ and charging into battle on a couple of stumps, which sounds like a Monty Python sketch.

Ivar met a nasty end in 873 when he ‘died of a sudden hideous disease…thus it pleased God.’ After which he was undoubtedly known as Ivar the Lifeless.

Brian Boru

(c. 941–1014)

In school we all learned that Brian Boru was the Irish hero that saved us from the nasty horrible Vikings and not only that, he was so pious that he was at prayer when a Viking buried a hatchet in his head. So not only did he enjoy Irish hero status but almost sainthood as well. But that’s mostly a load of oul’ bollox. Having said that, there were elements of truth in what was battered into us. Brian did put an end to any serious remnants of Viking power and, to be fair to the fecker, he was arguably one of Ireland’s greatest military leaders, so he does deserve some of the legendary status.

Many people also mistakenly believe that Brian was a Jackeen, primarily because his most famous battle was in Clontarf. Others think he was from the Meath area because he was a High King. But no, Brian was a big Culchie galoot. Think of him like a big hairy Fianna Fáil cute hoor, but with a helmet and a shield.

Brian hailed from Killaloe in beautiful Clare, the Da being Cennétig Mac Lorcáin, the local king, and the Mammy being Bé Binn inion Urchadh (possibly ‘Binny’ for short, as saying things like ‘Is me shirt washed yet, Bé Dinn inion Urchadh?’ could be a bit of a mouthful). Poor Binny was hacked to death during a Norse raid when Brian was a youngfella, which for some reason gave him a dislike of the dirty big Scandinavians.

His big brother, Mathgamain (whose name evolved into ‘McMahon’), inherited the kingship. Their main foe was a Viking mentaller called Ivar of Limerick. When Mathgamain agreed a truce with Ivar, Brian would have none of it and took to the hills, launching guerrilla-style attacks against Norse settlements. He was a fierce tactician and often defeated vastly superior numbers, leaving Ivar with a right puss. Brian’s fame spread and Mathgamain decided it was time to kiss and make up with his brother, and so told Ivar to feck off. The brothers then marched on Ivar’s forces, beat the crap out of them and sent Ivar legging it out of Ireland. But a few years later he snuck back and killed Mathgamain. Brian then challenged Ivar to open combat, during which he dispatched the Norseman to Valhalla.

Now king, he decided to take on his brother’s old enemies and expand his kingdom a tad. At the time there were over 100 local kings in Ireland. Some were quite powerful, but others’ kingdoms were roughly the size of a soggy beermat. Brian led his armies to victory after victory, and in 978, he defeated the King of Cashel and became King of Munster.

But he wasn’t finished yet and his gaze turned towards Leinster, Meath and Connaught, where there were lots more little and large Irish kings and smelly Norsemen. Brian cleverly used the Shannon as a means of getting his armies up around Connaught and Meath, and it was through this he developed his tactical skills, by combining naval and land forces to encircle his enemies. His raids went on for 15 years from 982, which really pissed off the High King, Máel Sechnaill mac Domnaill.

Now poor Máel has really been robbed of his rightful place in history, because in 980, at the Battle of Tara, he inflicted a crushing defeat on Olaf Cuaran, Viking King of Dublin. Olaf was the last powerful Norse king in Ireland and it was this victory and not Brian’s at Clontarf that ended any serious Viking power. But unfortunately Máel’s name is a bit tricky to pronounce whereas Brian Boru has a bit of alliteration going for it and easily trips off the tongue, and such are the whims of history.

In 997, Máel Sechnaill agreed a truce, Brian getting basically the bottom half of Ireland and Máel getting the rest. This didn’t go down well with Máel’s former allies and so they gave him the boot as King of Leinster (although he was still High King of Ireland) and replaced him with another Máel – Máel Morda Mac Murchada, who launched a rebellion against Brian and his lads. Máel Morda allied himself with his Viking cousin, Sigtrygg Silkbeard, who was the incumbent Viking King of Dublin, and in 999, the opposing armies met at the Battle of Glenmáma in Wicklow.

According to ancient texts, the rebels had the shite kicked out of them by Brian, losing 7000 men. But Brian decided to be merciful to the Viking leader and not only allowed him remain as King of Dublin, but gave him one of his daughters in marriage. He probably thought it was a good way to stop her freeloading off him. He also took the young Sigtrygg’s Mammy, called Gormflaith, as his own bride, and at the time it must have been one big happy family because Gormflaith was also Máel Morda’s sister. Got all that?

Now, getting back to the other Máel, the High King, with whom Brian had made a truce years beforehand. Well, Brian decided he wasn’t happy with only half of Ireland, he now wanted the bleedin’ lot. So the fecker conveniently forgot about the truce and launched an attack on Meath. In 1002, it is recorded that Máel Sechnaill threw up his hands and said he’d had enough of this High King shite. And so Brian was finally acknowledged by most of Ireland as High King. The only bit left was Ulster, and those northern boys weren’t going to quit without a fight.

It took 10 long years before Brian overcame the gansey-load of Ulster kingdoms. He did it by again combining land and sea forces, attacking along the coast while his land forces trapped the enemy from the other side. He consolidated his power by getting the Catholic Church onside, first of all, by giving them loads of free gold. He made Armagh the religious capital and forced others to make regular contributions, so the church decided it would be handy to keep Brian in power, as he made them lots of dosh. He also rebuilt churches that the Vikings had banjaxed and generally made himself best buddies with all the bishops.