Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

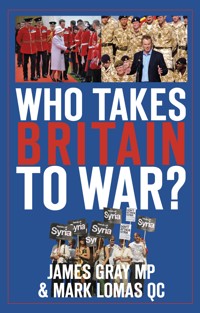

The long-standing parliamentary convention known as the 'Royal Prerogative' has always allowed Prime Ministers to take the country to war without any formal approval by Parliament. The dramatic vote against any military strike on Syria on 29 August 2013 blew that convention wide open, and risks hampering Great Britain's role as a force for good in the world in the future. Will MPs ever vote for war? Perhaps not – and this book proposes a radical solution to the resulting national emasculation. By writing the theory of a Just War (its causes, conduct and ending) into law, Parliament would allow the Prime Minister to act without hindrance, thanks not to a Royal Prerogative, but to a parliamentary one.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 251

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This book was inspired by the work I did on a mid-term thesis as a student at the Royal College of Defence Studies in 2003. It was entitled ‘Crown vs Parliament: Who decides to go to War?’1 I am immodestly proud that it won a silver model of the RCDS ‘beast’ as a prize, and was published in the Seaford House Papers. It was written shortly after Tony Blair gave the House of Commons a vote on hostilities against Saddam Hussain.

Major General Keith Cima was my inspiration and mentor at RCDS, and General Sir Tim Granville-Chapman made many suggestions for improvements to that paper, and has also kindly contributed a foreword to this book.

I am indebted to the House of Commons Library, in particular to Claire Mills and Richard Kelly, whose detailed research papers, Parliamentary Approval for Deploying the Armed Forces: An Introduction to the Issues,2 and an update to it in February 2013, I have quoted and used extensively. Richard Kelly also kindly read the final draft of the text, and corrected a number of details.

James de Waal’s paper, ‘Depending on the Right People, British Political-Military Relations, 2001–10’,3 which is a closely connected, but parallel, discussion to this one, made a particularly useful contribution to Chapter 8. The clerks and specialist advisers to the House of Commons Defence Committee, the Public Administration and Political and Constitutional Reform Select Committees and the House of Lords Select Committee on the Constitution have had their work quarried extensively (as is largely acknowledged in the endnotes and bibliography).

My friend, Mark Lomas QC, contributed the fascinating historical insight in Part Three, as well as a host of corrections, suggestions and debates about the rest of it. Mark’s robust conclusion to his historical section is a cri de coeur for constitutional stability. He is a true constitutional conservative and would much rather the system developed over centuries be retained. I, by contrast, regretfully acknowledge that there has been a fundamental change in the British Constitution, which has potentially devastating consequences for our ability to use military force in the future and that we must now do something about it if we are to maintain our role in world affairs.

I am grateful to Jacob Rees-Mogg MP, Madeleine Moon MP, Rt Hon. James Arbuthnot MP, Rosemary Fisher, Adam Fico, Anya Boulton and my wife, Philippa, for their detailed comments on the manuscript. Shaun Barrington and his colleagues at The History Press have been efficient, firm, unfailingly courteous and helpful. The errors and conclusions remain Mark Lomas’ and my responsibility.

James Gray

House of Commons

Notes

1Seaford House Papers, 2003.

2 House of Commons Library Research papers 08/88.

3 Chatham House, 2013.

CONTENTS

Title

Acknowledgements

Foreword by General Sir Tim Granville-Chapman GBE, KCB, ADC Gen.

Introduction

Part One: Who Takes Britain To War Now?

1 X Factor War

2 Can War Be Democratic?

Part Two: Who Will Take Britain to War in the Future?

3 Democracy or Strategy?

4 What Is War?

5 Why War?

6 The Just War

7 How the Americans Do It

8 The Royal Prerogative, Democracy and the Just War

Part Three: Who Used to Take Britain to War?

9 Divine Right of Kings?

10 The Prerogative and Popular Democracy

11 Modern Times: The Prerogative Challenged

Appendix: Wars Since 1700

Bibliography

About the Authors

Copyright

FOREWORD

This is an important book. The events in August 2013, when Parliament was invited to vote on the appropriate action over the Syrian crisis, marked a turning point in our constitutional history, displacing the long-standing position that decisions over going to war are a matter for exercise of the Royal Prerogative, manifest these days in the Prime Minister and his cabinet. It is possible that few people in this country realised that so significant a change had happened. In an engaging way, James Gray explains what occurred and why and what it means. On the other hand, most people would recognise that conflict increasingly bears on this country’s way of life in a global world, often feel threatened by the uncertainty it provokes, and that they are sometimes affected by the harm it brings. At the same time the emphasis on accountability for major decisions continues to grow, with the feeling that Parliament is often the means of achieving that goal. What is probably less understood is the extent to which decision-making that can lead to the lowest common denominator of agreement often serves the nation ill when its security is at stake. Many of those who threaten us, notably in the terrorist domain, are quick to exploit such weakness. So this book about strategic decision-making is timely. The early twenty-first-century solution to the dilemma we face between democratic accountability and the need to protect the nation will not be quick in coming, but this book sets the stage well for debate. It is to be hoped that responsible debate will follow – and soon. If it does not there is a real danger that we shall sleepwalk into a position where our influence in world affairs markedly declines, with far-reaching consequences for the well-being of the next generation.

General Sir Timothy Granville-Chapman

GBE, KCB, ADC Gen.

General Sir Timothy Granville-Chapman is a former Vice-Chief of the Defence Staff of the British Armed Forces. He presently holds the ceremonial position of Master Gunner, St James’s Park.

INTRODUCTION

Who decides on Britain’s wars? Who declares war, orders troops into action, commands them in action and decides how it’s all going to end?

Originally it was the King; then the King in concert with the feudal barons. That slowly evolved into the King in Council; then, as Parliament increased its power, it evolved again into the King acting through his prime minister. After that, war-making powers devolved wholly to the Prime Minister and Cabinet. But the power they were exercising was always the same: the ancient ‘Royal Prerogative’ of the monarch to take his country to war.

Those powers had evolved in the British Constitution over many hundreds of years. Their use waxed and waned. Yet, as we hope to demonstrate in this book, the reliance on the Royal Prerogative in war-making survived pretty well unscathed into the twenty-first century.

Leaving aside for a moment the 2003 Iraq War, which was something of an anomaly, there was not much of an assault on its constitutional impregnability until 29 August 2013. That was the day on which Prime Minister David Cameron gave the House of Commons the final say over whether or not to launch an air strike against Syria. Leave aside, for the moment, the pretty universal view that any such strike would have been the wrong thing to do. The right outcome does not necessarily justify the wrong process leading to it. For, by allowing the House of Commons to have the final say in the matter, Mr Cameron ended the centuries-long convention that it should be the Prime Minster in Cabinet who decides on war, albeit always ultimately answerable to Parliament for his decisions.

‘So ended the great war of 1878-80 … We had 70,000 men in Afghanistan, and even then we really only held the territory within the range of our guns.’ General Sir John Miller Adye.

Now, it is perfectly true that the convention of the Royal Prerogative had been questioned by many parliamentarians and constitutional theorists for some time. It had become an increasingly common belief in recent years that taking the country to war was a matter that must be decided not by the monarch and his privy council, nor by the Prime Minister and his cabinet acting in the monarch’s name, but more properly by the elected representatives of the people – Members of Parliament, sitting in the House of Commons.

Democrats and parliamentarians may well argue that a full and substantive debate on military intervention, such as that on 29 August 2013, has great advantages. Surely it is only right that MPs – the tribunes of the people – should have the final say over that most devastating of all decisions – to go to war? It is too grave and weighty a decision, they would argue, to leave to any one person. It must have collective approval or we should not do it; and Parliament is the ultimate distillation of the collective views of the nation. Surely it should therefore be Parliament who decides? What’s more, this strengthens Parliament vis-à-vis the Executive, and as such can only be a good thing.

There is, of course, great strength in most of those arguments. Yet is it not at least possible that this apparent ‘democratisation’ of war may have long-term and extensive consequences for our ability as a nation to do what is right and necessary in military terms around the world? If, in future, it is backbench MPs who determine our military deployments overseas, will we ever make any? Will they be the right ones, and carried out with the speed and secrecy necessary to make them successful? All of these questions are critical to Britain’s future role on the world stage.

So, David Cameron’s apparently terminal abandonment of the use of the Royal Prerogative in war-making over Syria may well have wide-ranging constitutional, military and diplomatic consequences for Britain. This book will examine the development of war-making, from all-powerful medieval monarchs through unquestioned use of the Royal Prerogative by prime ministers, to this current fashion for democracy. It will consider how it happened, and the long-term consequences. It outlines some of the many possible downsides to excessive democracy in war-making; and it discusses the dilemma which these two competing pressures – democracy and military effectiveness – produce.

Gurkhas of 1RGR prepare for what became known as the ‘Lam Death March’, Operation Southern Scorpion, February 2008. In all, 400 troops would thrust into 3,000 square kilometres of Taliban territory north of Kandahar province. (Image courtesy of Nick Allen, from Embed: To the End with the World’s Armies in Afghanistan)

Finally, the outline of a solution is suggested, which would satisfy calls for democracy in war-making while still preserving the ability of the government to do what is right in the world.

PART ONE: WHO TAKES BRITAIN TO WAR NOW?

BY JAMES GRAY MP

1

X FACTOR WAR

Order, Order. The Ayes to the right were 272 and the Noes to the left were 285. So the Noes have it, the Noes have it.1

So it was that the Right Honourable John Bercow MP, Speaker of the House of Commons, announced on 29 August 2013 that rockets would not rain down on Syria the following weekend as the Prime Minister had apparently intended. Perhaps unknowingly, he was making constitutional history as he said it.

History has been ‘made’ in the chamber of the House of Commons on thousands of occasions over the centuries. Most of the great events in British history have been marked by important parliamentary debates and votes – wars; strikes; abdications; the creation of the National Health Service; budgets; Queen’s Speech debates and the making or breaking of governments. Usually, these great and historic occasions are well noticed and marked by press and public alike. But just occasionally, parliamentary history is ‘made’ more or less unnoticed by parliamentarians or the wider world.

So it was on that Thursday, at 10.31 p.m. The House had been recalled for the specific purpose of agreeing to a limited American-led military strike against President Assad’s regime in Syria. President Barack Obama had concluded that Assad had crossed a ‘red line’ by using chemical weapons against his own people. He planned to take military action against Syria as a result, and sought support from his oldest allies – Britain and France – in doing so. Their governments had apparently agreed in principle. But the UK Prime Minister, David Cameron, was mindful of promises he had made some years previously (in Opposition) that he would never take the country to war without the explicit approval of the House of Commons. In a speech as Leader of the Opposition in 2006, for example, Mr Cameron had said:

I believe the time has come to take a look at those powers exercised by Ministers under the Royal Prerogative. Giving Parliament a greater role in the exercise of these powers would be an important and tangible way of making government more accountable. Just last week we first heard about the government’s decision to send 4,000 troops to Afghanistan in the pages of the Sun newspaper …2

He was referring to the deployment into the Sangin area of Afghanistan’s Helmand Province which, unannounced to Parliament, had occurred the previous week.

The Democracy Task Force he had established to look into the matter reported on 6 June the following year:

We believe that it is no longer acceptable for decisions of war and peace to be a matter solely for the Royal Prerogative. The Democracy Task Force therefore recommends that a Parliamentary Convention should be established that Parliamentary assent – for example, the laying of a resolution of the House of Commons – should be required in timely fashion before the commitment of any troops …3

During the very recent parliamentary debate on the deployment of forces in Libya on 21 March 2011, the Foreign Secretary, William Hague, had gone one step further:

We will also enshrine in law for the future the necessity of consulting Parliament on military action.4

So by August 2013, and despite his (presumably conditional) promise to Barack Obama that the UK would assist with the deployment of military force in Syria, David Cameron really had no choice but to consult Parliament on the matter. In doing so, he was breaching many hundreds of years of practice; he was establishing what could be a dangerous precedent for the future; and he was taking a substantial political gamble – and one which he in fact lost. For, until that evening, surprising as it may seem, going to war had never before been subject to formal parliamentary approval (with the possible exception of the debates just prior to the start of the Iraq War in 2003).

Yet on this occasion, Mr Cameron insisted that, irrespective of the merits and demerits of a strike against Syria, it could only be sanctioned by a substantive vote in the House. He recalled parliamentarians a few days early from their summer recess, in the hope of securing the authority he needed to support our oldest ally in their plan. Yet in doing so, he cannot have taken proper account of public opinion, nor of how that would be reflected in the views of the MPs of his own party. The tide of British public opinion, still scarred by Iraq and Afghanistan, was running strongly against military intervention anywhere else in the world, and the returning backbenchers, on Wednesday 28 August, were well aware of it. Even the most hawkish of Tory MPs, and even those in the safest of safe Conservative seats, would have been keenly aware of local opinion; of the threat from UKIP; and of the risk of non-reselection by their own Conservative Associations if they did not do the right thing. We can only imagine that David Cameron personally supported air strikes against Assad, and that he blithely thought that his backbenchers would be of like mind. He could not have been more wrong in that judgement.

It is widely assumed – although not proven in documents – that the Prime Minister was planning to table a parliamentary motion approving such air strikes or other military action against Assad. Military assets of various kinds had been deployed to Cyprus and elsewhere already, and there was a widespread presumption in military circles that action was imminent – in the air if not (yet) on the ground. The use of chemical weapons was widely decried, and Labour’s Ed Miliband had indicated in television interviews that Labour would support such government action. Had that been the case, the recall of Parliament would have been largely symbolic, parliamentarians no doubt simply using the occasion to publicly reiterate their abhorrence of the use of these vile weapons, and the Prime Minister duly being given authority to act alongside the US in punishing Assad for his use of them. Given Labour’s presumed support for the motion, it must have seemed a relatively straightforward piece of parliamentary and political manoeuvring, and American and British rockets could have started to land on specified targets within Syria by the following weekend.

It was not to be. Smelling the political coffee, Mr Miliband conducted a last minute U-turn and announced that the Labour Party would not be supporting the government nor any kind of military action against Syria. Without Labour, and with Mr Cameron’s Lib. Dem. coalition partners split and vacillating on the matter, only a handful of Tory dissidents would mean that the Prime Minister would lose the vote on any such motion.

No public records exist of the meetings which must have occurred that day between the Prime Minister and the Conservative Chief Whip, Sir George Young, but there can be little doubt that the ‘Chief’ would have been frank about the scant likelihood of securing a Commons majority for military action in Syria, since Labour were now lining up with Tory rebels to oppose it.

‘Prime Minister, you are risking a humiliating defeat over this,’ Sir George would have said. ‘There is no precedent for a Prime Minister losing a parliamentary vote called to approve his decision to go to war. We have recalled Parliament, and so to face such a humiliation is a very high-risk strategy.’

Perhaps as a result of such advice as that, and as a result of the very many meetings which he himself had with unhappy backbenchers on the subject, the Prime Minister was forced to water down the motion he laid before Parliament that Thursday. It would now merely decry Assad’s use of chemical weapons; it would call for the UN Inspectors to be allowed to visit the sites in question; it would demand talks in Geneva; and crucially it would promise a further House of Commons vote prior to any possible British military involvement.

The formal motion read:

That this House:

Deplores the use of chemical weapons in Syria on 21 August 2013 by the Assad regime, which caused hundreds of deaths and thousands of injuries of Syrian civilians;

Recalls the importance of upholding the worldwide prohibition on the use of chemical weapons under international law;

Agrees that a strong humanitarian response is required from the international community and that this may, if necessary, require military action that is legal, proportionate and focused on saving lives by preventing and deterring further use of Syria’s chemical weapons;

Believes, in spite of the difficulties in the United Nations [whose Security Council had failed to reach unanimous resolution to take action, thanks to vetoes from Russia and China], that a United Nations process must be followed as far as possible to ensure the maximum legitimacy for any such action;

Believes that the United Nations Security Council must have the opportunity to [consider the briefing from their investigating team on the ground in Syria] and that every effort must be taken to secure a Security Council Resolution backing military action before any such action is taken;

Notes that before any direct British involvement in such action a further vote in the House of Commons will take place;

And notes that this Resolution relates solely to efforts to alleviate humanitarian suffering by deterring use of chemical weapons and does not sanction any action in Syria with wider objectives.5

It is hard to know how any Parliamentarian could have objected to such a watered-down motion, yet Labour felt the necessity to table its own counter-motion. It read:

This House:

Expresses its revulsion at the killing of hundreds of civilians in Ghutah, Syria on 21 August 2013;

Believes that this was a moral outrage;

Recalls the importance of upholding the worldwide prohibition on the use of chemical weapons;

Makes clear that the use of chemical weapons is a grave breach of international law;

Agrees with the UN Secretary General that UN weapons inspectors must be able to report …

Supports steps to provide humanitarian protection to the people of Syria but will only support military action involving UK forces if and when the following conditions have been met:

That the weapons inspectors must have concluded their work and reported to the Security Council; there must be compelling evidence … The UN Security Council must have voted on it; that there is a clear legal basis for taking collective military action …; that such action must be legal, proportionate and time-limited;

and that the PM must report back to the House on the achievement of these conditions so that the House can vote on UK participation in such action …6

This counter-motion is, of course, astonishingly similar to the government motion. It is pretty anodyne, and crucially also calls for a second House of Commons vote before any action. It can only have been tabled for straightforward party political reasons – so that Labour could try to position itself as the anti-war party, presumably in the hope that commentators would not actually bother to read the precise terms of either their or the government’s motions.

It is hard to understand why any parliamentarian, no matter how ‘dovelike’ and anti-war they may have felt, could possibly have objected to either motion. It is even harder to know why the Conservatives voted against the Labour motion, which was as easy on the eye as their own. Nonetheless, for reasons best known to their whips, the Coalition voted down the Labour motion; and then Labour and the Tory rebels voted down the government motion. So, quite contrary to urban memory of the occasion, the House of Commons ended up accepting no motion at all on Syria, despite the fact that both would have been so very easy to accept by any sensible person.

The following historic – if largely ignored – exchange then occurred at 10.31 p.m., just after Mr Speaker had announced the result of the vote:

Edward Miliband: ‘On a point of order, Mr Speaker. There having been no motion passed by this House tonight, will the Prime Minister confirm to the House that, given the will of the House that has been expressed tonight, he will not use the Royal Prerogative to order the UK to be part of military action before there has been another vote in the House of Commons?’

The Prime Minister: ‘Mr Speaker, I can give that assurance. Let me say that the House has not voted for either motion tonight. I strongly believe in the need for a tough response to the use of chemical weapons, but I also believe in respecting the will of this House of Commons. It is very clear tonight that, while the House has not passed a motion, the British Parliament, reflecting the views of the British people, does not want to see British military action. I get that, and the Government will act accordingly.’7

This brief exchange, late one Thursday evening, is of huge importance in so many different ways. The least important but most intriguing element is the baffling illogicality of both men’s argument that, despite the House of Commons having come to no formal resolution, it was somehow nonetheless clear that the House was opposed to war. After all, for all we know, some members may have been opposed to the UK being involved on any basis; some may have been in favour of immediate air-strikes but opposed to UN involvement; some may even have been opposed to the principle of putting the matter to a motion. We will never know. How either party leader was able to divine the ‘will of the House’ from the rejection of both motions remains a mystery. Yet, however they came to be uttered, the consequences for the history of the Middle East as a whole, and for Syria in particular, of these unscripted remarks late at night after such an astonishing parliamentary shambles, are yet to be calculated.

For there then followed a series of more or less haphazard events in London and Washington. Prompted by the Commons vote on that historic evening – or perhaps seizing on it as a way of escaping from a possibly rash threat against Assad (what one official later described as his ‘get out of jail free card’) – President Obama confirmed that he too would seek the support of Congress for military action. While waiting for Congress to be in session, Secretary of State Kerry made an apparently off-the-cuff remark to the effect that he would accept Syrian chemical disarmament if it was supervised by Russia. Russia and Syria indicated that they would be content with that, which allowed President Obama to avoid any vote in Congress; and indeed to avoid war. Diplomatic negotiations amongst the various parties ensued in Geneva; Syria allowed access to most of their chemical weapons sites by inspectors; the chemical weapons were (we hope) largely destroyed; and a military strike with potentially global consequences was avoided – at least for now.

It appeared that the pacifist will of the people of the UK, expressed by their MPs in two negative votes – and the failure of the House to come to any very clear conclusion – had led to a respite for Syria from Allied retribution. (A subsequent reopening of negotiations with Iran over their nuclear ambitions may also be indirectly linked.)

Leaving aside the immediate diplomatic and military consequences of these events, 29 August 2013 also had significant and historic consequences for the British Constitution, for our standing in the world, and for our future ability to take any kind of military action. Mr Cameron’s conceding a substantive parliamentary vote on whether or not to embark on military action before it took place may well have profound consequences for Britain’s foreign policy and global positioning and ability to act for the good in the future.

Alistair Burt, the then Foreign Office Minister with responsibility for the Middle East, was interviewed by the Guardian on Monday 30 December, and described the consequences of the events of 29 August as:

A constitutional mess in which the Commons can be guaranteed to back intervention only to defend the Falkland Islands and Gibraltar … I think we can assume those. I am not sure that we can assume anything else. Where does that leave us and our partnerships around the world?8

We have put ourselves in a Constitutional mess this way. I think Government needs to take executive action in foreign affairs. It informs Parliament. If Parliament does not ultimately go for it, then the issue becomes a vote of confidence issue. I don’t think you can handle foreign affairs by having to try to convince 326 people [a majority of MPs] each time you need to take a difficult decision. You do it and if they don’t like it they can vote you out and they can have a general election.

As we will describe in later chapters, this is a brief but accurate summary of the nature and extent of parliamentary control over a war-making process that had held good from at least March 1782 until August 2013.

Alistair Burt’s comments run directly counter to the earlier view expressed by his close ally, William Hague, who had promised legislation to enshrine the right of Parliament to decide. One wonders if Mr Burt’s conversion, despite the clear view of his erstwhile boss, may be a post-Syria ‘straw in the wind’. It may yet be that Mr Cameron and Mr Hague will come to regret their pre-election promise to consult the House of Commons on going to war. We shall see.

It was certainly interesting to see an unnamed ‘senior Foreign Office source’ quoted in the same Guardian article:

… Voicing the hope that Britain would not lose its ability to act militarily and diplomatically … Two key reasons for our diplomatic strength are our status as one of the five permanent members of the UN Security Council … and our ability to be more flexible, adaptable and nimble than others – both diplomatically and militarily. I really hope that the lesson from August’s parliamentary vote is that however we take decisions about military action in the future, we do so in a way that preserves rather than constrains our comparative advantage (or our ability to be nimble).

This was another brief, accurate and deadly summary of the potential effect of the ill-considered and mismanaged proceedings on the floor of the House of Commons on that shambolic August evening.

Since 1782, when Prime Minister Lord North had resigned after a complex series of negotiations over reinforcing our troops in the American War of Independence, prime ministers of all shades engaged in a variety of military activities without formally consulting Parliament. As an illustration, it may surprise you to learn that 1968 is the only year since 1945 in which no British service person has been killed on active service. Yet none of those wars were formally approved by a vote in Parliament before they had commenced. How can that have occurred? How can Prime Ministers over a period of at least 231 years – and monarchs for centuries before that – have engaged in such a wide variety of wars and military engagements without risking a Cameron-style parliamentary defeat over them? Is it that all of those wars and engagements were popular? Surely not. Perhaps previous Parliaments have been more subservient and respectful to the Prime Minister? But that 231 years spans the high tide of parliamentary scrutiny and control of the Executive. Perhaps the cases for going to war were clearer and stronger than that advanced by Mr Cameron with regard to Syria? Hardly likely.