34,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

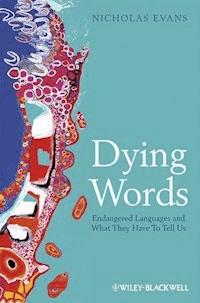

- Herausgeber: John Wiley & Sons

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Serie: The Language Library

- Sprache: Englisch

A gripping and moving text which explores the wealth of human language diversity, how deeply it matters, and how we can best turn the tide of language endangerment

In the new, thoroughly revised second edition of Words of Wonder: Endangered Languages and What They Tell Us, Second Edition (formerly called Dying Words: Endangered Languages and What They Have to Tell Us), renowned scholar Nicholas Evans delivers an accessible and incisive text covering the impact of mass language endangerment. The distinguished author explores issues surrounding the preservation of indigenous languages, including the best and most effective ways to respond to the challenge of recording and documenting fragile oral traditions while they’re still with us.

This latest edition offers an entirely new chapter on new developments in language revitalisation, including the impact of technology on language archiving, the use of social media, and autodocumentation by speakers. It also includes a number of new sections on how recent developments in language documentation give us a fuller picture of human linguistic diversity. Seeking to answer the question of why widespread linguistic diversity exists in the first place, the book weaves in portraits of individual “last speakers” and anecdotes about linguists and their discoveries. It provides access to a companion website with sound files and embedded video clips of various languages mentioned in the text. It also offers:

- A thorough introduction to the astonishing diversity of the world’s languages

- Comprehensive exploration of how the study of living languages can help us understand deep human history, including the decipherment of unknown texts in ancient languages

- Discussions of the intertwining of language, culture and thought, including both fieldwork and experimental studies

- An introduction to the dazzling beauty and variety of oral literature across a range of endangered languages

- In-depth examinations of the transformative effect of new technology on language documentation and revitalisation

Perfect for undergraduate and graduate students studying language endangerment and preservation and for any reader who wants to discover what the full diversity of the world’s languages has to teach us, Words of Wonder: Endangered Languages and What They Tell Us, Second Edition, will earn a place in the libraries of linguistics, anthropology, and sociology scholars with a professional or personal interest in endangered languages and in the full wealth of the world’s languages.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 772

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

THE LANGUAGE LIBRARY

The Language Library was created in 1952 by Eric Partridge, the great etymologist and lexicographer, who from 1966 to 1976 was assisted by his co-editor Simeon Potter. Together they commissioned volumes on the traditional themes of language study, with particular emphasis on the history of the English language and on the individual linguistic styles of major English authors. In 1977 David Crystal took over as editor, and The Language Library now includes titles in many areas of linguistic enquiry.

The most recently published titles in the series include:

Ronald Carter and Walter Nash Seeing Through Language

Florian Coulmas The Writing Systems of the World

David Crystal A Dictionary of Linguistics and Phonetics,

Sixth Edition

J. A. Cuddon A Dictionary of Literary Terms and Literary

Theory, Fourth Edition

Viv Edwards Multilingualism in the English-speaking World

Nicholas Evans Words of Wonder: Endangered Languages and What

They Have to Tell Us, A Second Edition of Dying Words

Amalia E. Gnanadesikan The Writing Revolution: Cuneiform to the Internet

Geoffrey Hughes A History of English Words

Walter Nash Jargon

Roger Shuy Language Crimes

Gunnel Tottie An Introduction to American English

Christopher Upward and George Davidson The History of English Spelling

Ronald Wardhaugh Investigating Language

Proper English: Myths and Misunderstandings about Language

Words of Wonder

Endangered Languages and What They Tell Us

Second Edition

Nicholas Evans

This edition first published 2022

© 2022 John Wiley & Sons Ltd

Edition History

John Wiley & Sons Ltd (1e, 2010)

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, except as permitted by law. Advice on how to obtain permission to reuse material from this title is available at http://www.wiley.com/go/permissions.

The right of Nicholas Evans to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with law.

Registered Office

John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030, USA

John Wiley & Sons Ltd, The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, UK

Editorial Offices

9600 Garsington Road, Oxford, OX4 2DQ, UK

For details of our global editorial offices, customer services, and more information about Wiley products visit us at www.wiley.com.

Wiley also publishes its books in a variety of electronic formats and by print-on-demand. Some content that appears in standard print versions of this book may not be available in other formats.

Limit of Liability/Disclaimer of Warranty

While the publisher and authors have used their best efforts in preparing this work, they make no representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the contents of this work and specifically disclaim all warranties, including without limitation any implied warranties of merchantability or fitness for a particular purpose. No warranty may be created or extended by sales representatives, written sales materials or promotional statements for this work. The fact that an organization, website, or product is referred to in this work as a citation and/or potential source of further information does not mean that the publisher and authors endorse the information or services the organization, website, or product may provide or recommendations it may make. This work is sold with the understanding that the publisher is not engaged in rendering professional services. The advice and strategies contained herein may not be suitable for your situation. You should consult with a specialist where appropriate. Further, readers should be aware that websites listed in this work may have changed or disappeared between when this work was written and when it is read. Neither the publisher nor authors shall be liable for any loss of profit or any other commercial damages, including but not limited to special, incidental, consequential, or other damages.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the Library of Congress

Paperback ISBN: 9781119758754; ePub ISBN: 9781119758778; ePDF ISBN: 9781119758761

Cover image: Courtesy of Manuel Pamkal. Photo © Top Didj & Art Gallery, Katherine, Northern Territory, Australia

Cover design by Wiley

Set in 9.5/12.5pt STIXTwoText by Integra Software Services Pvt. Ltd, Pondicherry, India

Contents

Cover

THE LANGUAGE LIBRARY

Title Page

Copyright

Preface to the Second Edition

Acknowledgments for the First Edition

Prologue

About the Companion Website

Part I The Library of Babel

1 Warramurrungunji’s Children

2 Four Millennia to Tune In

Part II A Great Feast of Languages

3 A Galapagos of Tongues

4 Your Mind in Mine: Social Cognition in Grammar

Part III Faint Tracks in an Ancient Wordscape: Languages and Deep World History

5 Sprung from Some Common Source

6 Travels in the Logosphere: Hooking Ancient Words onto Ancient Worlds

7 Keys to Decipherment: How Living Languages Can Unlock Forgotten Scripts

Part IV Ratchetting Up Each Other: The Coevolution of Language, Culture, and Thought

8 Trellises of the Mind: How Language Trains Thought

9 What Verse and Verbal Art Can Weave

Part V On the Brink

10 Listening While We Can

Part VI Afterword

Epilogue: In the Shade of the Casuarina

Outro: Reawakening the Word

References

Maps

Index of Languages and Language Families

Index

End User License Agreement

List of Figures

Chapter 1

Figure 1.1 Clans and languages in...

Figure 1.2 Archi men herding sheep...

Figure 1.3 A group of Seri...

Chapter 2

Figure 2.1 Fray Bernardino de Sahag...

Figure 2.2 Page from the Florentine...

Figure 2.3 Franz Boas as anthropology...

Figure 2.4 Franz Boas as Kwakiutl...

Figure 2.5 Hidatsa speaker Margaret Haven...

Figure 2.6 A

dilsiz

...

Chapter 3

Figure 3.1 Navajo code-talkers Cpl...

Figure 3.2 Speakers of !Xó...

Figure 3.3 The polysemous sign ‘...

Figure 3.4 How to push lumpy...

Chapter 4

Figure 4.1 A Matses hunter returning...

Figure 4.2 A generic model for...

Chapter 5

Figure 5.1 Sir William ‘Oriental...

Figure 5.2 Proto-Indo-European and...

Figure 5.3 Three generations of Indo...

Figure 5.4 The Algic languages.

Figure 5.5 Family tree of the...

Figure 5.6 The Afroasiatic languages.

Chapter 6

Figure 6.1 Distribution of place names...

Figure 6.2 Distribution of the Austronesian...

Figure 6.3 Austronesian family tree showing...

Figure 6.4 Four reconstructed named items...

Figure 6.5 Distribution of the Yeniseian...

Figure 6.6 A Ket shaman, photographed...

Figure 6.7 The Roma migrations from...

Chapter 7

Figure 7.1 and Figure 7.2 Tangut stupa at the...

Figure 7.3 Nine times in perils...

Figure 7.4 Water-pool jaguar and...

Figure 7.5 Languages of the Caucasus...

Figure 7.6 St. Catherine’s...

Figure 7.7 Letters from the Caucasian...

Figure 7.8 An Olmec Figure, la...

Figure 7.9 The La Mojarra Stela...

Figure 7.10 The Mixe-Zoquean languages...

Figure 7.11 The Epi-Olmec syllabary...

Chapter 8

Figure 8.1 Jack Bambi telling the...

Figure 8.2 The rotation test for...

Figure 8.3 Nine-year-old Hai...

Figure 8.4 Initial stimuli in the...

Figure 8.1 Sample absolute response of...

Figure 8.6 An old Aymara speaker...

Figure 8.7 A younger Spanish-speaking...

Figure 8.8 Gestures accompanying descriptions of...

Figure 8.9 Contrasting placement-event categorization...

Figure 8.10 Pairs of contrasting scenes...

Chapter 9

Figure 9.1 Languages and song types...

Figure 9.2 Avdo Međedovi...

Figure 9.3 Paulus Konts performing...

Figure 9.4 Leo Moses and Tony...

Chapter 10

Figure 10.1 Manuel Pamkal and Nicholas...

Figure 10.2 Saem Majnep at work...

List of Tables

Part 3

Table P3.1 Grouped ‘cognate...

Chapter 1

Table 1.1 Clans and languages...

Table 1.2 The top 25...

Chapter 2

Table 2.1 From ox to...

Chapter 3

Table 3.1 Senary-power numerals...

Chapter 4

Table 4.1 ‘For’...

Chapter 5

Table 5.1 Germanic

h

: Latin

k

: Russian...

Table 5.2 The plot thickens...

Table 5.3 Possessive paradigm showing...

Table 5.4 Examples of plural...

Chapter 6

Table 6.1 Some reconstructable proto...

Table 6.2 Sample vocabulary items...

Table 6.3 Reflexes of proto...

Table 6.4 Vocabulary strata in...

Chapter 8

Table 8.1 Kayardilt compass-point...

Table 8.2 The many ways...

Chapter 9

Table 9.1 Some Nuu-chah...

Chapter 10

Table 10.1 Krauss’ schema...

Guide

Cover

THE LANGUAGE LIBRARY

Title page

Copyright

Table of Contents

Preface to the Second Edition

Acknowledgments for the First Edition

Prologue

About the Companion Website

Begin Reading

Epilogue: In the Shade of the Casuarina

Outro: Reawakening the Word

References

Maps

Index of Languages and Language Families

Index

End User License Agreement

Pages

i

ii

iii

iv

v

vi

vii

viii

ix

x

xi

xii

xiii

xiv

xv

xvi

xvii

xviii

xix

xx

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

108

109

110

111

112

113

114

115

116

117

118

119

120

121

122

123

124

125

126

127

128

129

130

131

132

133

134

135

136

137

138

139

140

141

142

143

144

145

146

147

148

149

150

151

152

153

154

155

156

157

158

159

160

161

162

163

164

165

166

167

168

169

170

171

172

173

174

175

176

177

178

179

180

181

182

183

184

185

186

187

188

189

190

191

192

193

194

195

196

197

198

199

200

201

202

203

204

205

206

207

208

209

210

211

212

213

214

215

216

217

218

219

220

221

222

223

224

225

226

227

228

229

230

231

232

233

234

235

236

237

238

239

240

241

242

243

244

245

246

247

248

249

250

251

252

253

254

255

256

257

258

259

260

261

262

263

264

265

266

267

268

269

270

271

272

273

274

275

276

277

278

279

280

281

282

283

284

285

286

287

288

289

290

291

292

293

294

295

296

297

Preface to the Second Edition

It is a great privilege to be able to republish this book in a second edition. I poured my soul into the first edition, but we now know so much more about the world’s fragile linguistic heritage than we did in 2009. Public awareness has grown, first with the declaration of the International Year of Indigenous Languages in 2019 and then with its upgrading to the International Decade of Indigenous Languages, starting from 2022, the year this book appears. Changes in publishing technology mean that this second edition can have accompanying media files, bringing to life the speakers, sounds, and gestures of the languages of the people of this book, and overcoming some of the barriers that bristling sequences of phonetic symbols can present to readers. Technological advances demanded a major refreshing of several parts of the book. Finally, many readers of the first edition noticed errors in the first edition, which I am happy to fix here.

Perhaps most significant is the change in the book’s title. The back story to the original title is that there had been pressure to include the term ‘language death’. This is a problematic concept, for reasons I will give in a moment. The original title, ‘Dying Words: Endangered Languages and What They Have to Tell Us’ tried to avoid some of that alarmist baggage, partly by the deliberate ambiguity of the title (invoking the seriousness of a dying person’s last words), and partly by displacing the loss from whole languages onto simply the loss of words. After all, even a language in rude health, like English, is constantly seeing some of its words become obsolete. However, this was not enough to prevent the title causing offence to many First Nations people from around the world, who are justifiably fed up with being told by assimilationist governments and organizations that their cultures and languages are dying out. In my own country, Australia, ‘smoothing the pillow of a dying race’ was one of the more offensive phrases used to denigrate, and to try to prevent, indigenous moves to ensure the retention of their own language and culture. In the 12 years since the first edition appeared, so many First Nations peoples have told me stories of their languages ‘going underground’ – out of earshot of the hegemonic apparatus who would exact punishment or even imprisonment – that the folly and arrogance of presuming ‘language death’ in such fraught colonializing circumstances has become painfully apparent. And the many astonishing language revival programmes that have unfolded in recent years give hope for the prospects of turning the tide of language endangerment.

On top of that, several reviewers of the first edition (e.g., Enfield 2011) pointed out that the book was about what languages in general have to teach us, not just endangered ones. Japanese, Spanish, and Turkish, for example, each feature in the book, but can hardly be considered endangered. I do not, however, think it is a coincidence that it was the act of writing a book about language endangerment that led to this all-embracing view of the wonders of language. It is, after all, in contemplating death that we become most intensely aware of all that life has to offer. So, with the revised title I have tried to strike a better balance between the wonder that linguistic diversity presents to us, whether endangered or not, and the endangerment and fragility that still faces the vast majority of the world’s languages.

Revisiting a book beginning as a time-situated narrative two decades ago poses certain problems of exposition. For good reason, I began and ended the first edition in real time – starting with the death of my Ilgar teacher Charlie Wardaga in 2003, when I first sat down to begin the book, and ending with the death of my Kayardilt teacher Pat Gabori shortly before the book went to press in 2009. That narrative wrapped the story of me writing the book around the lives and deaths of these two key people who taught me so much, and I have kept it here. However, I have added a further chapter at the end (an Outro)1 to give the new and more hopeful view that befits this beginning of the International Decade of Indigenous Languages. In adding this new material, situated in the rather different world of 2022, I adopt the novelist’s tool of a double-time perspective, so as to keep the immediacy of the original text while adding updates where appropriate. To avoid confusion, I use the original tense (as at the first edition) in the Prologue, first chapter, and Epilogue, but the tense corresponding to my time of writing the revisions, in 2021–2, in the introduction to the Afterword and in the Outro. In the remaining chapters of the book, I have adjusted the tense to reflect the time of this second edition.

Another difficult authorial choice has to do with the terminology to be used for the original custodians of lands and waters that were invaded by colonizing powers with an accelerated tempo over the last half millennium. According to different terminologies in use in modern nations, First Nations, Indigenous, Aboriginal, Autochthonous, Tribal, and other terms are each preferred in some places. Yet most of these terms have also accrued unwelcome connotations in some other time and place. Aiming for a global readership, and in the hope that the book will keep being read for some years, even as such terms continue to evolve, I am painfully aware that somewhere in the world, at some time, one of my word choices in this domain may cause offence. I apologize in advance, and can only express the hope that my deep respect for the languages and cultures I am talking about in this book will come through regardless.

The many acknowledgments I incurred in writing the original version of the book are given in the Acknowledgements to the First Edition, included after this one, but here I would like to thank a number of other people who have helped me with this second edition: Manuel Pamkal for agreeing to make an adaptation of his painting Katherine River in Flood1998 available to use as the cover, as well as being a dear friend and inspired language teacher, Alex and Petrena Ariston of Top Didj & Art Gallery, Katherine, Australia, for their help obtaining a good cover image, three anonymous reviewers of my proposal for the second edition, Amina Mettouchi and Michael Walsh who kindly read and commented on new material and chapters, Naijing Liu for helping with the initial manuscript revisions, and Hannah Lee, Rachel Greenberg, and Clelia Petracca from Wiley for guiding this second edition through the production process. I’d especially like to thank Keira Mullan for her meticulous work on the long and complex task of getting the final version of the manuscript ready.

Many readers of the first edition kindly sent me corrections, which I’ve incorporated into this second edition, and I thank them all for their help, particularly Bruce Fleming, David Harmon, and Haun Saussy. Translators of the Chinese, French, German, Japanese, and Korean editions also picked up a number of bloopers in the original, now corrected, and I thank: Robert Mailhammer, Wakata Mori, Masayuki Onishi, Toshiki Osada, Marc St-Upéry, Kihyuk Kim, Jeong-Eun Jeong, Yaching Tsai, and Shiyuan (William) Wang. Comments by Nick Enfield, Bill Hanks, David Harmon, and Nicholas Rothwell in their reviews of the first edition helped me reconceptualize some aspects of the revisions. Others helped me with specific language data, sometimes audio or audiovisual, for incorporation into this second edition: here I thank Zurab Baratashvili (Georgian), Matthew Carter (chasing up Ket sound files), Charbel El-Khaissi (Arabic), Elhoussaine Naciri and Hannah Sarvasy (Tashelhit Berber), Bruno Olsson (Marind), Valentina Andreevna Romanenkova (Ket), Amiran Basilashvili, Giorgi Kumsiashvili, Beka Neshumashvili, Simon Neshumashvili and Olga Tigirova-Kumsiashvili (Udi), and McComas Taylor (Sanskrit). I am also grateful to many other people whose conversation and correspondence have pointed me to specific sources or suggested ideas useful in revising for the second edition: Joanne Allen, Rob Amery, Danielle Barth, Henrik Bergqvist, Lindell Bromham, Niclas Burenhult, Kenan Celik, Michael Christie, Eve Clark, Terra Edwards, Lizzie Marrkilyi Ellis, Daan van Esch, James Essegbey, José Antonio Flores Farfán, Ben Foley, Jennifer Green, Bernd Heine, Robin Hide, Darja Hoenigman, John Justeson, Haroun Kafi, Terry Kaufman, Inge Kral, Lucía Lezama, Bryan MacGavin, Asifa Majid, Felicity Meakins, Amina Mettouchi, Rachel Nordlinger, Rafael Núñez, Carmel O’Shannessy, Manuel Pamkal, Mark Richards, Lila San Roque, Aung Si, Jane Simpson, Sharman Stone, Myf Turpin, Ed Vajda, Jacques Vernaudon, Janet Wiles, Lesley Woods, and Ewelina Wnuk. For showing the viability of language revival, against many odds and in many ways, I thank Jack Buckskin (Kaurna), Stan Grant Snr and Elaine Lomas (Wiradjuri), Jaky Troy (Ngarigu), Caroline Hughes and Brad Bell (Ngunnawal), a special conference I was privileged to attend at Ka Haka ‘Ula O Ke‘elikōlani at the University of Hawai‘i at Hilo, and Ghil’ad Zuckermann for a number of exchanges. For the preparation of the revised versions of the maps from the first edition I thank Jenny Sheehan (Cartogis ANU) and Chandra Jayasuriya (University of Melbourne).

I would also like to thank the people of Bimadbn and surrounding villages in Papua New Guinea for their extraordinary hospitality and insights into the Nen language and the complex multilingual ecology still thriving in the area, which has had a major impact on how I think about multilingualism as well as opening up a whole new linguistic world – Jimmy Nébni, Goe Dibod, Grmbo Blba, Mary Dibod, and Doreen Wenembu have been particularly supportive. Since the first edition was published, I have also had the good fortune to be involved in several initiatives that have reshaped my views on language in many ways, including projects on the languages of Southern New Guinea, on the grammar of social cognition, on the Wellsprings of Linguistic Diversity (ARC Laureate Project), and on the Dynamics of Language (ARC Centre of Excellence) – I thank the Australian Research Council (ARC), the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation, the Volkswagen Foundation (DoBeS – Dokumentation Bedrohter Sprachen), the Arcadia Foundation/SOAS (ELDP – Endangered Languages Documentation Program), the Australian National University, and the Universität zu Köln for their support, financial, personal and social, which has shaped the contents of this book in many ways.

Note

1

I deliberately use this word to make the point that word-birth is going on just as word-death is (see the case of English

fell

I discuss on p. 90): something old, something new. In this case the word

outro

– first documented in 1967, in the context of popular music, a blend of

out

and

intro

, has not yet made it into the same academic register in which words like Epilogue and Envoi still claim their place, though they sound increasingly fusty to many and may not keep their place at the table for ever.

Acknowledgments for the First Edition

My first debt is to the speakers of fragile languages who have welcomed me into their communities and their ways of talking, thinking, and living. †Darwin and May Moodoonuthi adopted me as their tribal son in 1982 and they and the rest of the Bentinck Island community taught me their language as if I were a new child. The community has extended its love and understanding to me and my family ever since, despite the tragically premature deaths of so many of its members. I particularly thank †Darwin Moodoonuthi, †Roland Moodoonuthi, †Arthur Paul, †Alison Dundaman, †Pluto Bentinck, †Dugal Goongarra, †Pat Gabori, †May Moodoonuthi, Netta Loogatha, †Olive Loogatha, †Sally Gabori and †Paula Paul. Since then I have had the good fortune to be taught about other Aboriginal languages by †Toby Gangele, †Minnie Alderson, †Eddie Hardie, †Big John Dalnga-Dalnga and †Mick Kubarkku (Mayali, Gun-djeihmi, Kuninjku and Kune dialects of Bininj Gun-wok), †David Kalbuma, †Alice Boehm, †Jack Chadum, †Peter Mandeberru, †Jimmy Weson, †Maggie Tukumba (Dalabon), †Charlie Wardaga (Ilgar), †Mick Yarmirr (Marrku), †Tim Mamitba, †Brian Yambikbik, †Joy Williams, †Khaki Marrala, †Mary Yarmirr, †David (‘Cookie’) Minyumak and †Archie Brown (Iwaidja). Each of these people, and many others too numerous to name and thank individually here, is linked in my mind to vivid and powerful moments as, in their own resonant languages, they discussed things I had never attended to or thought about before.

I would also like to thank my teachers and mentors in linguistics for the way they have imbued the field with fascination and insight: Bob Dixon, Bill Foley, Igor Mel’cuk, Phil Rose, †Tim Shopen, and Anna Wierzbicka during my initial studies at the Australian National University, and as mentors in my subsequent career Barry Blake, Melissa Bowerman, †Michael Clyne, Grev Corbett, Ken Hale, Larry Hyman, Steve Levinson, Francesca Merlan, Andy Pawley, Frans Plank, Ger Reesink, Peter Sutton, and Alan Rumsey. Many of the ideas touched upon here have developed during conversations with my colleagues Felix Ameka, Alan Dench, Janet Fletcher, Cliff Goddard, Nikolaus Himmelmann, Pat McConvell, Tim McNamara, Rachel Nordlinger, Ilia Peiros, Lesley Stirling, Nick Thieberger, Jill Wigglesworth, and David Wilkins, my students Isabel Bickerdike, Amanda Brotchie, Nick Enfield, Sebastian Fedden, Alice Gaby, Nicole Kruspe, Robyn Loughnane, and Ruth Singer, and my fellow fieldworkers Murray Garde, Bruce Birch, Allan Marett, and Linda Barwick.

In putting this book together I have been overwhelmed by the generosity of scholars from around the world who have shared with me their expertise on particular languages or fields and I thank the following: Abdul-Samad Abdullah (Arabic), Sander Adelaar (Malagasy and Austronesian more generally), Linda Barwick (Arnhem Land song language), Roger Blench (various African languages), Marco Boevé (Arammba), Lera Boroditsky (various Whorfian experiments), Matthias Brenzinger (African languages), Penny Brown (Tzeltal), John Colarusso (Ubykh), Grev Corbett (Archi), Robert Debski (Polish), Mark Durie (Acehnese), Domenyk Eades (Arabic), Carlos Fausto (Kuikuro), David Fleck (Matses), Zygmunt Frajzyngier (Chadic), Bruna Franchetto (Kuikuro), Murray Garde (Arnhem Land clans and languages, Sa language of Vanuatu), Andrew Garrett (Yurok), Jost Gippert (Caucasian Albanian), Victor Golla (Pacific Coast Athabaskan), Lucia Golluscio (indigenous languages of Argentina), Colette Grinevald (Mayan, languages of Nicaragua), Tom Güldemann (Taa and Khoisan in general), Alice Harris (Udi), John Haviland (Guugu Yimithirr, Tzotzil), Luise Hercus (Pali and Sanskrit), †Jane Hill (Uto-Aztecan), Kenneth Hill (Hopi), Larry Hyman (West African tone languages), †Rhys Jones (Welsh), Russell Jones (Welsh), Anthony Jukes (Makassarese), Dagmar Jung (Athabaskan), Jim Kari (Dena’ina), Sotaro Kita (gesture in Japanese and Turkish), Mike Krauss (Eyak), Nicole Kruspe (Ceq Wong), Jon Landaburu (Andoke), Mary Laughren (Wanyi), Steve Levinson (Guugu Yimithirr, Yélî-Dnye), Robyn Loughnane (Oksapmin), Andrej Malchukov (Siberian languages), Yaron Matras (Romani), Peter Matthews (Mayan epigraphy), Patrick McConvell (various Australian), Fresia Mellica Avendaño (Mapudungun), Cristina Messineo (Toba), M. Miles (Ottoman Turkish Sign Language), Marianne Mithun (Pomo, Iroquoian), Claire Moyse-Faurie (New Caledonian languages), Lesley Moore (Mandara Mountains), Valentín Moreno (Toba), Hiroshi Nakagawa (|Gui and Khoisan in general), Irina Nikolaeva (Siberian languages), Mimi Ono (|Gui, and Khoisan generally), Toshiki Osada (Mundari), Nick Ostler (Aztec, Sanskrit and many others), Midori Osumi (New Caledonian languages), Aslı Özyürek (Turkish gesture, Turkish Sign Language), Andy Pawley (Kalam), Maki Purti (Mundari), Bob Rankin (Siouan), Malcolm Ross (Oceanic languages), Alan Rumsey (Ku Waru; New Guinea Highlands chanted tales), Christfried Naumann (Taa), Miren Lourdes Oñederra (Basque), Valentin Peralta Ramirez (Nahuatl/Aztec), Richard Rhodes (Algonquian), Malcolm Ross (Oceanic languages), Geoff Saxe (Oksapmin counting), †Wolfgang Schulze (Caucasian Albanian/Udi), Peter Sutton (Cape York languages), McComas Taylor (Sanskrit), Marina Chumakina (Archi), Nick Thieberger (Vanuatu languages; digital archiving), Graham Thurgood (Tsat and Chamic), Mauro Tosco (Cushitic), Ed Vajda (Ket and other Yeniseian), Rand Valentine (Ojibwe),†Dave Watters (Kusunda/Mihaq), Tony Woodbury (Yup’ik), Kevin Windle (Slavic), Yunji Wu (Chinese), Roberto Zavala (Oluteco, Mixe-Zoquean), and Ulrike Zeshan (Turkish Sign Language).

A big thanks to those who arranged for me to visit or meet with speakers of a wide range of languages around the world as I researched this book: Zarina Estrada Fernandez (northern Mexico), Murray Garde (Bunlap Village, Vanuatu), Andrew Garrett (Yurok, northern California), Patricia Shaw (Musqueam Community in Vancouver), Lucia Golluscio (Argentina), Nicole Kruspe (Pos Iskandar and Bukit Bangkong, Malaysia), the Mayan language organization OKMA and its director Nik’t’e (María Juliana Sis Iboy) in Antigua, Guatemala, and especially Roberto Zavala and Valentín Peralta Ramirez for a memorable journey down through Mexico to Guatemala. Not all these stories made it through to the final, pruned manuscript, but they all shaped its spirit.

A number of institutions and programmes have given me indispensable support in researching and writing this book: the University of Melbourne, the Australian National University, the Institut für Sprachwissenschaft, Universität zu Köln, the Alexander von Humboldt-stiftung, CIESAS (Mexico), OKMA (Guatemala), and the Universidad de Buenos Aires. Two other organizations whose ambitious research programmes have enormously expanded my horizons are the Max Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics in Nijmegen, and the Volkswagenstiftung through its DoBeS Program (Dokumentation bedrohter Sprachen) and in particular for its support of the Iwaidja Documentation Program. In this connection, I thank Vera Szoelloesi-Brenig for her wise stewardship of the overall programme, and many participants in the DoBeS program, especially Nikolaus Himmelmann, Ulrike Mosel, Hans-Jürgen Sasse, and Peter Wittenberg.

Publishing and Copyright Acknowledgments

The author and publisher gratefully acknowledge the permission granted to reproduce the copyright material in this book. The following sources and copyright holders for materials are given in order of appearance in the text.

Text Credits

Brown, Penelope. 2001. Learning to talk about motion UP and DOWN in Tzeltal: is there a language-specific bias for verb learning? In Language Acquisition and Conceptual Development, ed. Melissa Bowerman and Stephen C. Levinson. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 512–543. The second half of Brown’s figure 17.2 (p. 529) reproduced here as Table 8.2 with permission of Cambridge University Press.

Cann, Rebecca. 2000. Talking trees tell tales. Nature 405(29/6/00): 1008–1009. Quote from Cann (2000: 1009) reprinted with permission of Macmillan Publishers Ltd.

Fishman, Joshua. 1982. Whorfianism of the third kind: ethnolinguistic diversity as a worldwide societal asset. Language in Society 11:1–14. Quote from Fishman (1982: 7) reprinted with permission of Cambridge University Press.

Hale, Ken. 1998. On endangered languages and the importance of linguistic diversity. In Endangered Languages: Current Issues and Future Prospects, ed. L. A. Grenoble and L. J. Whaley. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 192–216. Quote from Hale (1998: 211) reprinted with permission of Cambridge University Press.

Rogers, Henry. 2005. Writing Systems: A Linguistic Approach. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing. Material in Table 2.1 herein reprinted with permission of the author and Wiley-Blackwell.

Woodbury, Anthony. 1998. Documenting rhetorical, aesthetic and expressive loss in language shift. In Endangered Languages: Current Issues and Future Prospects, ed. L. A. Grenoble and L. J. Whaley. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 234–260. Quotes from Woodbury (1998: 250, 257) reprinted with permission of Cambridge University Press.

Other copyright holders are acknowledged in the text, as appropriate.

Figure and Table Credits

Figure 1.2 Courtesy of Marina Chumakina.

Figure 1.3 Arizona State Museum, University of Arizona, James Manson (photographer), JWM ASM-25114, reproduced with permission of the Arizona State Museum.

Figure in Box 1.1 Courtesy of Leslie Moore.

Table 1.2 Harmon, D. 1996 Southwest Journal of Linguistics.

Figure 2.1 Florida Center for Instructional Technology, University of South Florida, http://etc.usf.edu/clipart/25300/25363/sahagun_25363.htm.

Figure 2.2 Charles E. Dibble et al., / Reproduced with permission of the University of Utah Press.

Figure 2.3 American Philosophical Society, Franz Boas Papers, Collection 7. Photographs.

Figure 2.4 Reproduced with permission of the National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution (neg. no. 8300).

Figure 2.5 Ives Goddard / Reproduced with permission of the Indiana University Archives (P0108675).

Figure 2.6 Courtesy of Türk Kültürne Hizmet Vakfı.

Figure 3.1 Courtesy US National Archives, originally from US Marine Corps, No. 69889-B.

Figure 3.2 Photo courtesy of Christfried Naumann.

Figure Box 3.1 Reproduced with permission of the Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle.

Figure 3.3 p. 104 in Nancy Munn, Walbiri Iconography: Graphic Representations and Cultural Symbolism in a Central Australian Society (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1973), reprinted with permission.

Figures Box 3.2 Saxe, G. B. (1981) / John Wiley & Sons.

Figure 4.1 Courtesy of David Fleck.

Figure 4.2 Barth and Evans 2017/ University of Hawai‘i Press.

Figure 5.1 The National Library of Wales.

Figure in Box 5.1 Michael Krauss / Reproduced with permission of the University of Wisconsin Press.

Table 5.3 John Benjamins Publishing Company.

Figure 6.4 Ross et al. 1998: 77, 96, 218, 220/ Australian National University.

Figure 6.6 Reproduced with kind permission of Heinrich Werner.

Table 6.3 Ross et al. 1998: 96–97/ Australian National University.

Table 6.4 Cambridge University Press.

Figure 7.1 British Library Photo 392/29(95). © British Library Board. All rights reserved 392/29(95). Reproduced with permission.

Figure 7.2 Cook 2007: 6/ Unicode, Inc.

Figure 7.3 Azerbaijan International.

Figure 7.4 Houston and Stuart 1989: 1–16/ Center for Maya Research.Research.

Figure 7.6 Frontispiece in George H. Forsyth and Kurt Weitzmann, with Ihor Ševčenko and Fred Anderegg, The Monastery of Saint Catherine at Mount Sinai: The Church and Fortress of Justinian, Plates (Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press, 1973).

Figure 7.7 Alexidze and Blair 2003/ Azerbaijan International.

Figure 7.9 Kaufman and Justeson 2001/ University at Albany.

Figure 8.1 Courtesy of Steven Levinson; transcriptions and translations from Haviland 1993.

Figure 8.3 Kind permission of Daniel Haun.

Figure 8.4 R. Núñez, et al. ‘Absolute spatial frames of reference in bilingual speakers of endangered Ryukyuan Languages: an assessment via novel gesture elicitation’, Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the Cognitive Science Society 41, 890–896 (2019), reprinted with permission.

Figure 8.5 R. Núñez, et al. ‘Absolute spatial frames of reference in bilingual speakers of endangered Ryukyuan Languages: an assessment via novel gesture elicitation’, Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the Cognitive Science Society 41, 890–896 (2019), reprinted with permission.

Figure 8.6 Núñez and Sweetser 2006: 430. Reproduced by permission of Wiley.

Figure 8.7 Núñez and Sweetser 2006: 430. Reproduced by permission of Wiley.

Figure 8.8 Frames extracted from the video files of experiments reported in Sotaro Kita and Aslı Özyürek, ‘What does cross-linguistic variation in semantic coordination of speech and gesture reveal? Evidence for an interface representation of spatial thinking and speaking’, pp. 16–32 from Journal of Memory and Language 48 (2003). Reproduced with permission.

Figure 8.9 Bowerman 2007, with permission.

Figure 8.10 Modified from Choi et al. 1999.

Figure 9.2 Milman Parry Collection, MPC0750. Reproduced with the permission of the Milman Parry Collection of Oral Literature at Harvard University.

Figure 9.3 Courtesy of Don Niles.

Figure 9.4 Mary Moses, reprinted with permission of Tony Woodbury.

Figure 10.2 Courtesy of John Dumbacher.

Figure in Box 10.1 Dave Watters.

Figure (a) in Box 10.4 Mara Satos.

Figure (b) in Box 10.4 Vincent Carelli.

Figure O.2 Courtesy of Jennifer Green.

Figure in Box O.3 Courtesy of Cristina Messineo.

Figure in Box O.4 Amaigh Languages.

For permission to use the painting ‘Katherine River in Flood 1998’ on the cover of this book, I would like to thank artist Manuel Pamkal, as well as Petrena Ariston of Top Didj & Art Gallery for supplying the image photograph.

Every effort has been made to trace copyright holders and to obtain their permission for the use of copyright material. The publisher apologizes for any errors or omissions in the above list and text, and would be grateful if notified of any corrections that should be incorporated in future reprints or editions of this book.

Prologue

No volverá tu voz a lo que el persa

Dijo en su lengua de aves y de rosas,

Cuando al ocaso, ante la luz dispersa,

Quieras decir inolvidables cosas

Un vieillard qui meurt est une bibliothèque qui brûle.

You will never recapture what the Persian

Said in his language woven with birds and roses,

When, in the sunset, before the light disperses,

You wish to give words to unforgettable things

(Borges 1972: 116–117)1

An old person dying is a library burning.

(Amadou Hampâté Bâ, address to UNESCO, 1960)2

Pat Gabori, Kabararrjingathi bulthuku,3 is, at the time I write these words, one of eight remaining speakers of Kayardilt,4 the Aboriginal language of Bentinck Island, Queensland, Australia. For this old man, blind for the past four decades, the wider world entered his life late enough that he never saw how you should sit in a car. He sits cross-legged on the car seat facing backwards, as if in a dinghy. Perhaps his blindness has helped him keep more vividly alive the world he grew up in. He loves to talk for hours about sacred places on Bentinck Island, feats of hunting, intricate tribal genealogies, and fights over women. Sometimes he interrupts his narrative to break into song. His deep knowledge of tribal law made him a key witness in a recent legal challenge to the Australian government, to obtain recognition of traditional sea rights. But fewer and fewer people can understand his stories.

Kayardilt was never a large language. At its peak it probably counted no more than 150 speakers, and by the time I was introduced to Pat in 1982 there were fewer than 40 left, all middle-aged or older.

The fate of the language was sealed in the 1940s when missionaries evacuated the entire population of Bentinck Islanders from their ancestral territories, relocating them to the mission on Mornington Island, some 50 km to the northwest. At the time of their relocation the whole population were monolingual Kayardilt speakers, but from that day on no new child would master the tribal language. The sibling link, by which one child passes on their language to another, was broken during the first years after the relocation, a dark decade from which no baby survived. A dormitory policy separated children from their parents during the day, and punished any child heard speaking an Aboriginal language.

Kayardilt, which we shall learn more about in this book, challenges many tenets about what a possible human language is. A famous article on the evolution of language by psycholinguists Steven Pinker and Paul Bloom, for example, proposed that ‘no language uses noun affixes to express tense’5 (grammatical time). This claim is in line with Noam Chomsky’s theory of Universal Grammar, which sees a prior restriction on possible human languages as essential to the language-learning child: it narrows down the set of hypotheses needed in deducing the grammar underlying the parents’ speech.

Well, Kayardilt blithely disregards this supposed impossibility, and marks tense on nouns as well as verbs. If you say ‘he saw (the) turtle’, for example, you say niya kurrijarra bangana. You mark the past tense on the verb kurrij ‘to see’, as -arra, but also on the object-noun banga ‘turtle’, as -na. Putting this into the future, to ‘he will see (the) turtle’, you say niya kurriju bangawu, marking futurity on both verb (-u) and noun (-wu). (Pronounce a, i, and u with their Spanish or Italian values, the rr as a trill, the ng as in singer, and the j as in jump.)6

Kayardilt shows us how dangerous it is to talk about ‘universals’ of language on the

basis of a narrow sample that ignores the true extent of the world’s linguistic diversity.7 Thinking about it objectively, the Kayardilt system isn’t so crazy. Tense locates the whole event in time – the participants, as well as the action depicted by the verb. The tense logics developed during the twentieth century plug whole propositions into their tense operators, including the bits denoted by both verbs and nouns in English. Spreading around the tense-marking, Kayardilt-style, shows the ‘propositional scope’ of tense.

But learning Kayardilt is not just a matter of mastering a grammar that no human language is supposed to have. It also requires you to think quite differently about the world. Try moving the eastern page of this book a bit further north on your lap. Probably you will need to do a bit of unfamiliar thinking before you can follow this instruction. But if you spoke Kayardilt, most sentences you uttered would refer to the compass points in this way, and you would respond instantly and accurately to this request.

Pat Gabori is in his 80s, and the youngest fluent speakers are in their 60s. So it seems impossible that a single speaker will remain alive when, in 2042, 100 years will mark the removal of the Kaiadilt people from Bentinck Island. In the space of a lifetime a unique and fascinating tongue will have gone from being the only language of its people, to a silent figment of the past.

Traveling 500 miles to the northwest we reach Croker Island in Australia’s Northern Territory. There, in 2003, I attended the funeral of Charlie Wardaga, my teacher, friend, and tribal elder brother. It was a chaotic affair. Weeks had passed between his death and the arrival of mourners, songmen, and dancers from surrounding tribes. All this time his body lay in a wooden European-style coffin, attracting a growing number of flies in the late dry-season heat, under a traditional Aboriginal bough-shade decked with red pennants in a tradition borrowed from those wide-ranging Indonesian seafarers, the Macassans. His bereaved wife waited under the bough-shade while we all came to pay our last respects, grasping a knife lying on the coffin and slashing our heads with it to allay our grief.

Later, as the men silently dug Charlie’s grave pit, the old women had to be restrained from leaping in. Then the searing, daggering traditional music gave way to Christian hymns more conducive to contemplation and acceptance. With this old man’s burial, we were not just burying a tribal elder pivotal in the life and struggles of this small community. The book and volume of his brain had been the last to hold several languages of the region: Ilgar, which is the language of his own Mangalara clan, but also Garig, Manangkardi, and Marrku, as well as more widely known languages like Iwaidja and Kunwinjku. Although we had managed to transfer a small fraction of this knowledge into a more durable form before he died, as recordings and fieldnotes, our work had begun too late. When I first met him in 1994, he was already an old man suffering from increasing deafness and physical immobility, so that the job had barely begun, and the Manangkardi language, for instance, had been too far down the queue to get much attention.

For his children and other clan members, the loss of such a knowledgeable elder took away their last chance of learning their own language and the full tribal knowledge that it communicated: place names that identify each stretch of beach, incantations for coaxing turtle to the sea’s surface, and the evocative lines of the Seagull song cycle, which Charlie himself had sung at other people’s funerals. For me, as a linguist, it left a host of unanswered questions. Some of these questions can still be answered for Iwaidja and Mawng, relatively ‘large’ related languages with around 200 speakers each; others were crucially dependent on Ilgar or Marrku data.

My sense of despair at what gets lost when such magnificent languages fall silent – both to their own small communities and to the wider world of scholarship – prompted me to write this book. Although my own firsthand experience has mainly been with fragile tongues in Aboriginal Australia and Papua New Guinea, similar tragedies are devastating small speech communities across the earth. Language death has occurred throughout human history, but among the 7000 or more modern languages the pace of extinction is quickening, and we are likely to witness the loss of half of humankind’s living tongues by the end of this century.8 On best current estimates, every two weeks, somewhere in the world, the last speaker of a fading language dies. No one’s mind will again travel the thought paths that its ancestral speakers once blazed. No one will hear its sounds again from a human mouth. And no one can go back to check a translation, or ask a new question about how the language works.

Each language has a different story to tell us. Indeed, if we record it properly, each will have its own library shelf loaded with grammars, dictionaries, botanical and zoological encyclopaedias, and collections of songs and stories. But language leads a double life, shuttling between ‘out there’ in the community of speakers and ‘in there’ in individual minds that need to know it all in order to use and teach it. So there come quiet moments of history when the whole accumulated edifice of an oral culture rests, unseen and unheard, in the memory of its last living witness.

So distinctive are many of these languages that, for certain riddles of humanity, just one language holds the key. But, we do not know in advance which language answers which question. And, as the science of language becomes more sophisticated, the questions we seek answers to are multiplying.

The task of recording the knowledge hanging on in the minds of Pat Gabori and his counterparts around the globe is formidable. For each language, the complexity of information we need to map is comparable to that of the human genome. But, unlike the human genome, or the concrete products of human endeavour that archaeologist’s study, languages perish without physical trace except in the rare cases where a writing system has been developed. As discernible structures, they only exist as fleeting sounds or movements. The classic goal of a descriptive linguist is to distil this knowledge, by a combination of systematic questioning and the recording and transcribing of whatever stories the speaker wishes to tell, into at least a trilogy of grammar, texts, and a dictionary. Increasingly this is supplemented by sound and video recordings that add information about intonation, gesture, gaze, and context, so that documentary linguists now go beyond what most investigators aspired to do 100 years ago. Revolutions in digital technology mean that linguists can now record and analyse more than they ever could, in exquisitely accurate sound and video, and archive these in ways that were unthinkable a generation ago. But despite this we can still capture just a fraction of the knowledge that any one speaker holds in their heads, and which – once the speaker population dwindles – is at risk of never coming to light because no one thinks to ask about it.

This book is about the full gamut of what we lose when languages fall silent, about why it matters, and about what questions and techniques best shape our response to this looming collapse of human ways of knowing. These questions, I believe, can only be addressed properly if we give the study of fragile languages its rightful place in the grand narrative of human ideas and the neglected histories of peoples who walked lightly through the world, without consigning their words to stone or parchment. And because we can only meet this challenge through a concerted effort by linguists, the communities themselves, and the lay public, I have tried to write this book in a way that speaks to all these types of reader.

The history of the field shows us that good linguistic description depends as much on the deep questions that linguists are asking as it does on the techniques that they bring to their field site. You only hear what you listen for, and you only listen for what you are wondering about. The goal of this book is to take stock of what we should be wondering about as we listen to the thousands of languages falling silent around us, across the totality of what Mike Krauss has christened the ‘logosphere’. Just as the ‘biosphere’ is the totality of all species of life and all ecological links on earth, the logosphere is the whole vast realm of the world’s words, the languages that they build, and the links between them. They are intimately intertwined, and we are just awakening to the full import of their looming collapse.

Further Reading

Important books covering the topic of language death and endangered languages include Kulick’s (2019) popular account of why children don’t learn their ancestral language, Tayap, in a remote village of Papua New Guinea, Campbell and Rehg (2018), Grenoble and Whaley (2012), Austin and Sallabank (2011). Among the older references that remain valuable are Grenoble and Whaley (1998), Crystal (2000), Nettle and Romaine (2000), and Harrison (2007).

A Note on the Presentation of Linguistic Material

One of the themes of this book is that each language contains its own unique set of clues to some of the mysteries of human existence. At the same time, the only way to weave these disparate threads together into a unifying pattern is on the loom of a common language, which in this book is English.

The paradox we face, as writers and readers about other languages, is to give a faithful representation of what we are studying in all its particularity, and at the same time to make it comprehensible to all who speak our language.

The biggest problem is how to represent unfamiliar sounds. Do we adapt the English alphabet, Berlitz-style, or do we use the technical phonetic symbols that, with their 600 or so letter-shapes, are capable of accurately representing each known human speech sound to the trained reader? Thus, we can use either English ng or the special phonetic symbol ŋ to write the sound in the Kayardilt word bangaa/baŋa: ‘turtle’ (a: represents a long a, so the whole word is pronounced something like bung-ah in English spelling conventions). Or we can write the Kayardilt word for ‘left’ as thaku, adapting English letters, but we then need to remember that the initial th, although it involves putting the tongue between the teeth like in English, is a stop rather than a fricative. It sounds like the d in width or the t in eighth – try watching your tongue in the mirror as you say these – and can be represented accurately by the special phonetic symbol t̪, where the little ̪ diacritic shows that the tongue is placed between the teeth: thus, t̪aku.

Since so many of the languages we will look at have sounds not easily rendered in English, I will sometimes need to use special phonetic symbols, which are spice to the linguist but indigestible to the lay reader. If you are in this latter category, just ignore the phonetic representation. When the point I am making depends on the pronunciation I will give a Berlitz-style rendition, but when it does not you should just work from the gloss and the English translation. Note also that, since some minority languages have developed their own practical orthographies (spelling systems), it is often more appropriate to write words in these rather than in standardized phonetic symbols. When possible I have included sound and video files in the accompanying material, so you can hear these words for yourself – such cases are shown by a indicating a sound file, and a indicating a video file.

In addition to the linguistic examples, I have had to decide what to do with the various quotes that pepper this book, from many languages and cultural traditions. In a book on the fragility of languages, this is not out of obscurity. A major cause of language loss is the belief that everything wise and important can be, and has been, said in English. Conversely, it is a great stimulant to the study of other languages to see what they express so succinctly. So, in general I have put such quotes first in their original language, followed by a translation (my own unless otherwise indicated). I hope the slightly greater effort this entails for you, the reader, will be rewarded by the treasures you will go on to discover.

Most languages mentioned in the book can be located from at least one map in the book, except for (a) national languages whose location is well known or deducible from the nation’s location, (b) ancient languages whose location is not known precisely, (c) scripts. If there is no explicit mention of the language’s location in the text, use the index at the back of the book to locate a relevant map.

Notes

1

The English translation of this poem is by Alistair Reid.

2

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=t1i3rweFa48

.

3

The Aboriginal people I refer to typically have a ‘whitefeller name’ and a traditional name, e.g., Pat Gabori and Kabararrjingathi bulthuku. Traditional names often have a strong element of privacy, sometimes even comparable to a pin number on a bank account, and are used sparingly if at all, so in general I will use their whitefeller names in this text.

4

Also spelled Kayardild in earlier publications; the more recent spelling is closer to how it sounds.

5

Pinker and Bloom (1990: 715).

6

And if we take more complicated sentences as examples, we see that other nouns (basically all nouns except the subject) also get the tense-marking. ‘He speared the turtle with big brother’s spear’ is

niya raajarra bangana thabujukarrangunina wumburungunina

:

thabujukarra

means ‘big brother’s’,

wumburung-

‘spear’,

-karra

‘belonging to’, and

-nguni

‘with, using’. As you can see, ‘turtle’, ‘big brother’s’, and ‘spear’ all get the past tense suffix

-na

. The instrumental suffix

-nguni

also ends up on all words in the noun phrase ‘big brother’s spear’. This penchant for agreement is another highly unusual characteristic of Kayardilt, which I do not go into here: it can lead to nouns stacking up four case suffixes at a stretch, to a level of complexity not found in any other human language – see Evans (1995a, 1995b, 2003b, 2006).

7

It turns out, in fact, that quite a number of languages mark tense on nouns – see Nordlinger and Sadler (2004) for a comprehensive survey and discussion.

8

For the moment I simply assert this figure, but we return to the grounds it is based on in

Chapter 10

.

About the Companion Website

Words of Wonder: Endangered Languages and What They Tell Us, Second Edition is accompanied by a companion website:

www.wiley.com/go/evans/wordsofwonder

The website includes:

Sound files which are indicated throughout the book with

Video files which are indicated throughout the book with

Part I The Library of Babel

Tuhan, jangan kurangisedikit pun adat kami.

Oh God, do not trima single custom from us.(Indonesian proverb)

Oh dear white1 children, casual as birds,Playing among the ruined languages,So small beside their large confusing wordsSo gay against the greater silences …

(Auden 1966)

In the biblical myth of the Tower of Babel, humans are punished by God for their arrogance in trying to build a tower that would reach heaven. Condemned to speak a babble of mutually incomprehensible languages, they are quarantined from each other’s minds. The many languages spoken on this earth have often seemed a curse to rulers, media magnates, and the person in the street. Some economists have even implicated it as a major cause of corruption and instability in modern nations.2

The benefits of communicating in a common idiom have led, in many times and places, to campaigns to spread one or another metropolitan standard – Latin in the Roman Empire, French in Napoleonic France, Mandarin in today’s China. Sometimes these are promoted by governments, but increasingly media organizations, aided by satellite TV, are doing the same: arguably Rupert Murdoch’s Star Channel is doing more to spread Hindi into remote Indian villages than 60 years of educational campaigning by the Indian government. We live today with an accelerating tempo of language spread for a few world languages – English, Chinese, Spanish, Hindi, Arabic, Portuguese, French, Russian, Indonesian, and Swahili. Another couple of dozen national languages are expanding their speaker bases toward an asymptote where all citizens of their countries speak the one language; at the same time, they are giving ground themselves in terms of higher education and technological literature to English and the other world languages.

Humankind is regrouping, away from their Babel, some millennia after sustaining their biblical curse.

But many other cultures have regarded language diversity as a boon. In Chapter 1 we shall begin by examining some alternative founding myths, widespread in small-scale cultures, that give very positive reasons for why so many languages are spoken on this earth. For the moment, though, let’s stick with the Babel version, but with the twist given to it by Jorge Luis Borges. His fabulous Library of Babel contains all possible books written in all possible languages, subject to a limit of 410 pages per tome. It thus contains all possible things sayable about the world, including everything that scientists, philosophers, poets, and novelists might express – plus every possible falsehood and piece of uninterpretable nonsense as well. (We can extend his vision a bit by clarifying that all possible writing systems are allowed – Ethiopic, Chinese, phonetic script, written transcriptions of sign languages, binary code of 0s and 1s ….)

For Borges, the Library of Babel was an apt metaphor because it allowed us to conceive a near-infinity of stories and ideas by increasing the number of languages they were written in, each idiom stamping its great masterpieces with the rhythm and take of a different world-view – Cervantes alongside Shakespeare, the Divine Comedy alongside the Popol Vuh, Lady Murasaki alongside Dostoyevsky, the Rig Veda alongside the Qur’an. (We can of course expand his idea to include stories told or chanted in the countless oral cultures of the world and that have yet to be written down – a topic we return to in Chapter 9.) As English, Spanish, Mandarin, and Hindi displace thousands of languages in the hearths of small communities, much of this library is now moulding away.

Our library will also contain grammars and dictionaries – of the 7000 or so languages spoken now,3 plus all that have grown and died since humans began to speak. (Of course, most of these grammars and dictionaries have still not been written, and those from vanished past languages never can be, but remember that Borges’ Library contains all possible books alongside its actual ones!) In this linguistic reference section of the library, we can read how, in the words of George Steiner, every language ‘casts over the sea its own particular net, and with this net it draws to itself riches, depths of insight, and lifeforms which would otherwise remain unrealized’.4

When we browse our way into this wing, we are looking not so much at what is ‘written in’ or ‘told in’ the languages – but what has been ‘spoken into’ them. By this I mean that speakers, in their quest for clarity and vividness, actually create new grammars and new words over time. Ludwig Wittgenstein once offered his famous advice Wovon man nicht sprechen kann, darüber muss man schweigen ‘what you cannot speak of, you must remain silent about.’ Fortunately, millennia of his predecessors ignored this injunction, in the process forging the languages that we use to communicate today. Untold generations, through their attempts to persuade and to explain, to move and to court, to trick and to exclude, have unwittingly built the vast, intricate edifices that collectively represent humankind’s most fundamental achievement, since without it none of the others could be begun. The contents of this wing of the library are also teetering on disrepair.