Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Peepal Tree Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

When Kei Miller describes these as essays and prophecies, he shares with the reader a sensibility in which the sacred and the secular, belief and scepticism, and vision and analysis engage in profound and lively debate. Two moments shape the space in which these essays take place. He writes about the occasion when as a youth who was a favoured spiritual leader in his charismatic church he found himself listening to the rhetoric of the sermons for their careful craft of prophecy; but when he writes about losing his religion, he recognises that a way of being and seeing in the world lives on - a sense of wonder, of spiritual empowerment and the conviction that the world cannot be understood, or accepted, without embracing visions that challenge the way it appears to be.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 280

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

ALSO BY KEI MILLER

Poetry

Kingdom of Empty Bellies

There is an Anger that Moves

Light Song of Light

The Cartographer Tries to Map a Way to Zion (forthcoming)

Fiction

The Fear of Stones and Other Stories

The Same Earth

The Last Warner Woman

Edited

New Caribbean Poetry: An Anthology

KEI MILLER

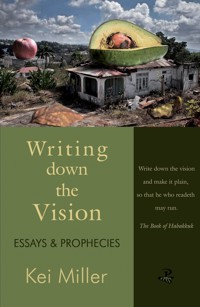

WRITING DOWN THE VISIONESSAYS & PROPHECIES

First published in Great Britain in 2013

Peepal Tree Press Ltd

17 King’s Avenue

Leeds LS6 1QS

England

© 2013 Kei Miller

ISBN 13 (PBK): 9781845232283

ISBN 13 (Epub): 9781845233211

ISBN 13 (Mobi): 9781845233228

All rights reserved

No part of this publication may be

reproduced or transmitted in any form

without permission

CONTENTS

Introduction and Acknowledgements

The Women Who Carried Pencils Behind Their Ears

The Texture of Fiction

In Defence of Maas Joe

These Islands of Love and Hate

A Kind of Silence

A Smaller Song

But in Glasgow, There Are Plantains

Imagining Nations

Writing with Elephants

My Mother’s Many Mouths

Making Space for Grief

What Names Recall

A Smaller Sound, A Lesser Fury – A Eulogy for Dub Poetry

An Occasionally Dangerous Thing Called “Nuance”

Maybe Bellywoman Was on “di Tape”

An Interview – composed of things asked, and things said, and things that were never said but maybe should have been

Riffing of Religion

A Space Between the Poems: An Attempt at a Benediction

Write down the vision and make it plain, so that he who readeth may run.– from The Book of Habakkuk

INTRODUCTION AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

My first book was a collection of short stories and it has occasionally baffled me that I have never returned to that genre. Looking at the pieces gathered here, I see now that I never left it. In a sense these are short stories even if they can’t be called “short-fiction”. The exception is the earliest piece collected here “A Kind of Silence”, but even this short story, towards its end, moves into a nonfictional mode.

There are those who say the short story is a natural genre for Caribbean writers but I find that argument a little patronizing. Proponents of the view say it is something about oral cultures and stories told by firesides and wise grandmothers and Anansi, and how all these things lend themselves to short rather than long fiction. Now there might actually be some truth to all of that, but I rather think that the Caribbean’s gravitation towards shorter pieces has to do with time and resources and publishing houses – things which writers of long fiction need to sustain their craft, and to which Caribbean writers have not had ready access. Instead we have written pieces that can fit inside newspapers or magazines or whatever small space has been offered us.

The pieces collected here were written in a variety of places – the earliest in Jamaica, a couple in Iowa, some in Glasgow, one in the Philippines, and so on. Two of these essays were posts on my blog. They are products of movement and migration, as obsessed with the Caribbean as with what it means to live and write away from home.

If on one hand these essays embrace narrative and exist on the border of the fictional “short story”, on the other hand they embrace polemic and exist on the border of prophecy. I imagine these as the sounds a man might make who has been living out in the wilderness, trying sometimes to shout and sometimes to whisper to the world in which he lives. As a collection, these represent something of my vision of the Caribbean seen from up-close and sometimes from afar, a vision I have been obsessed with writing down.

They are mostly occasional pieces, written on request for particular events or in response to particular situations. To those magazine editors and newspaper editors and conference organizers who made these requests, I would like to say thanks. So often, we are not short of things to say; we are only short of the spaces (however small) in which to say them.

“The Texture of Fiction” originally appeared in The Edinburgh Review.“These Islands of Love and Hate” originally appeared in The Glasgow Herald.“A Kind of Silence” originally appeared in the anthology Moving Right Along: Caribbean Stories in Honour of John Cropper.A larger essay, “The Art of Tongues, the Craft of Prophecy” eventually downsized itself to the current “The Women Who Carried Pencils behind their Ears” and originally appeared in PN Review.“A Smaller Song” was originally part of a presentation as the Bridget Jones Travel Bursary recipient at the Society of Caribbean Studies Conference. It subsequently appeared in my collection A Light Song of Light.“But in Glasgow, There are Plantains” originally appeared in The International Journal of Scottish Literature.“Imagining Nations” originally appeared in Moving Worlds.“Writing with Elephants” appeared first in Newbooks Magazine.“The Grief Spaces” was a commissioned travel essay for the US State Department.“A Smaller Sound, a Lesser Fury – a Eulogy for Dub Poetry” was a presentation at the Scottish Universities International Summer School.“Maybe Bellywoman Was on di Tape” was originally a keynote address at the Shadows and Shorelines conference at the University of Reading.“The Spaces between Poems” was a commissioned piece for the National Association of Literature Development’s Spring conference “The Spaces Between Us”.“In Defence of Maas Joe” and “An Occasionally Dangerous Thing Called ‘Nuance’” were originally posted as blogs on my website, keimiller.wordpress.com.THE WOMEN WHO CARRIED PENCILS BEHIND THEIR EARS(2007/2012)

Every writer is asked the same question over and over – who are the other writers that have influenced you the most? Put like that, the answers are easy enough for me: Lorna Goodison, Emily Dickinson, David Malouf, Kamau Brathwaite, for starters. But I think, better put, the question would be more amorphous – something like “who are the people or what are some of the things that have shaped your voice?” Then our answers wouldn’t be so easy. We would have to think through a more complicated genealogy that included songs, movies, grandparents, radio hosts, snippets of overheard speech. In my case it would include a few preachers and prophets, and also a wall.

There is Sister Gilzene – a thin elderly woman from the starch-stiff church I used to go to as a child, and whose eruptions of tongues into the sobriety of Sunday morning service was always smoothed away by a deacon, as if the old woman’s glossolalia existed in the creases of her purple frock – as if it was coming from her bunched shoulders and not from her mouth.

My genealogy would include Sister Sybil as well, another old woman, though larger in size than Gilzene. Hers was a great expanse of breasts and body and sound. She belonged to another church – the one I escaped to, before I escaped church altogether. It was a church that made space for eruptions, and when I used to go there, Sister Sybil’s uninterrupted tongues always had in it the resonance of thunder and the music of rain.

Sister Sybil has even made cameo appearances in my work. Sometimes by name:

Whenever Sister Sybil raise the red banner

the air change, the tempo change, the mood

change, and inside that place, God

begins to happen.1

And sometimes by image alone:

Because of her mountain breasts

she has learnt a peculiar walk, a duck-stride

to balance herself. It is hard to see anything

but the stern shifting of those mountains

when in flat, battleship shoes

she marches across the aisle.2

Sister Sybil had a talking parrot – maybe it is still alive – a vicious green thing who would demand peanuts then snap at your fingers. Strange the way she seemed to gift everything around her with language. Perhaps then Sybil, as in sibilant, or at a stretch, syllables. She was neither lovely nor lovable. She believed only in her God and the wretchedness of all mankind. I avoided her because even back then I never looked the part of a good Christian boy. My dreadlocks were particularly offensive. Whenever Sister Sybil spotted me she would try to lay heavy hands on my hair and pray.

It was Sister Sybil who once said to my friend when she was barely an eleven-year old girl, “Child! Me and de devil was fighting for yu soul last night!” Apocalyptic drama queen. She walked off after that, withholding from my friend the answer to the question that would haunt her for years – “Who won?”

My genealogy would include some whose names I have never known, like the bus preachers who would climb up onto the number 75 buses at Half-Way-Tree, their sermons lasting at least the five miles to Papine where I, caught up in their cadences, would have to reluctantly disembark. I remember one in particular who, in rebuking a woman for her less-than-noble career, accused her of dancing on tables and in skirts so short that he was able to see right up into her “birth-ina” – and it was this soldering together of words (not his condemnation) that made me appreciate that he was a wordsmith and that I belonged to his tribe.

My genealogy would have to include – most bizarrely – a concrete wall which despite its proximity to the sea and to salty air seemed never in danger of crumbling. In fact, this was a growing wall. The man who was forever adding to its height was quite clearly deranged. He wrote urgent messages onto the wall, hoping perhaps that the government or at least his neighbours would one day read them and heed his warnings. On Sunday evenings my father used to drive us out to Port Henderson for fried fish and bammy, and on the way back we would drive very slowly by this wall, and although we used to laugh, I think secretly we also found it beautiful. It was why we kept coming back. And it was something of a loss when the government really did seem to read it, or took notice of its height which broke every town planning rule and regulation, and so ordered it destroyed.

And the church women of my youth (Sister Gilzene and Sister Sybil), and the bus preachers on the number 75 bus, and that evergrowing wall, all belong to yet another genealogy. Each one of them, in their own way, is descended from a family of Jamaican “warner women”, those prophetesses of doom who used to carry pencils behind their ears. The pencils were supposed to represent a readiness to receive heavenly messages. Warner women would then pass on these messages to earthly citizens. Warner women connected the immediate worlds around them to what they understood was a larger truth.

Warner women would never confess to what I now understand is a complicated and a learned aesthetic – a careful craft of prophecy, a meditated art of speaking in tongues. One is not supposed to admit to artistry in what is supposed to be divinely inspired. And yet it is as much the art of these women, as it is that of Emily Dickinson, David Malouf and Lorna Goodison, that shapes my voice.

From the women who carried pencils behind their ears I learn that one is allowed to speak without irony – that most favoured mode of Western (and particularly British) writers, as if its use is the only way to signal a sharp and a nuanced intelligence, as if we have to always undercut the things we say and the things we most deeply believe in, lest we be accused of being precious or earnest. From the women who carried pencils behind their ears, I learn that it is okay to be loud and exclamatory, that power doesn’t always come from restraint and quietness, that sometimes power comes from power, and that some things are worth shouting about. From the women who carried pencils behind their ears I learn how to hold on to grief and onto myself and how to tremble at the strain. From them I even learn the use of metaphors – moons sinking in blood, alligators unable to walk on roads, as if to say – if you’re going to draw for the impossible, then make your imagination wide. Sometimes, it’s as if I have inherited their pencils and have begun to write down their visions.

End Notes

1. “Church Women: War Dance”, Kingdom of Empty Bellies (Coventry: Heaventree Press, 2005), p. 22.

2. “Church Women: Mother”, Kingdom of Empty Bellies, p. 12

THE TEXTURE OF FICTION(2007)

“It always amuses me that the biggest praise for my work comes for the imagination, while the truth is that there’s not a single line in all my work that does not have a basis in reality. The problem is that Caribbean reality resembles the wildest imagination.”

— Gabriel Garcia Marquez

I would like to offer you a rosary of stories in no particular order or scheme – all of them true, and about the place where I am from. I am from the Caribbean which is, incidentally, a much better thing to say than this other thing that has become popular: I am from the islands. “The islands” seem to me a phrase robbed of any geo-political or historical substance, a shell of a term offered so that the hearer, if not from our quaint and nebulous island (whether it be St Kitts, the Philippines, or Hawaii) can throw imaginary garlands of hibiscuses around our necks, imbuing us with all kinds of exotic baggage, and license and forgiveness. So I am from the Caribbean, and if you are not from there then the stories I tell you now might not make immediate sense. Or you might think I’m lying, or perhaps exaggerating. Sometimes Caribbean logic is its own.

In 2005 there was a woman who was killed twice – the second time at her own funeral. On the first occasion of her death it had been of natural causes. At her funeral the family gathered in large numbers, dressed in black or purple, with hymns in their mouths. But in the middle of tears and slow organ music, there was the sudden explosion of gunshots. Not a gun-salute; a gang war had broken out in the community around them, and then a bullet entered the church. I narrate this slowly, as if the bullet had politely opened the church door, took off its hat, apologized for interrupting and stated the nature of his business. Obviously this was not the case. It rudely shattered through the stained glass window, splintered through the closed coffin, and found its way into the heart of the dead woman, as if being an agent of death it was drawn immediately to the one life that wasn’t. Surprisingly, no one seemed thankful for the dead woman’s heroic act – how in pulling the bullet into herself she had likely been someone’s salvation. Instead the mourners complained at the injustice of the gang, their insensitivity towards the corpse – that being dead already there was no need for the bullet to make it unambiguous – and how the handsome coffin they had spent good money on was now ruined.

Recently, in my own country, we had a plague of baby crabs. It happened in the parish of St Thomas, in a seaside community. Everyone had gone to bed as usual but woke up during the night when they felt aggressive insects crawling onto their beds and over their feet, or dropping from the ceiling and into their open, snoring mouths. Imagine the spluttering and the flailing arms. Imagine the frantic lights being turned on everywhere until they discovered the tiniest of crabs, thousands and thousands of them, coming in with the moon tide, scuttling into the houses, covering all the surfaces. Doors were flung open and men, women and children ran. That night the whole community huddled on the road, a little distance away from their homes, some of them crying, most of them praying, looking anxiously to the sky to see if God was coming. God did not come, but the sun did, and with its early morning beams all the baby crabs, still scurrying around, were smitten dead. Only then could people return to their houses, rake the remnants of the plague out of their yards and back into the Caribbean sea which had brought them.

There is a haunted house in Guyana that has made me believe in the devil. In truth, I only saw the foundations of this house, because on the day that I got there, it was a week too late. Despite earnest protestations from the community, the house had been demolished. This was a humble peasant’s house, by the way, not the sprawling gothic mansion of similar American folklore. The first occupants had been a rice farmer, his wife and their three children. They lived, I imagine, in relative domestic happiness and turmoil. Then one night, the rice farmer decided it was a good idea to go to the room of his two older children and kill them. He went back to his own room and killed the baby, then his wife and then himself. In every world, in every language, this is a tragedy. So there was shock and there was mourning, and then a year had passed. The year passed and the house became simply what we call, a “dead-lef”, an inheritance waiting to be claimed. Into it moved a cousin of the rice farmer with his own wife and his own two children. They lived in that house in relative domestic happiness and turmoil, until one night the cousin went from room to room, killed his two children, then his wife, then himself. There was shock and there was mourning, and then a year had passed. Another relative moved into this tragic house, lived there for a year with his wife and three children. You know their destiny. One night the man grabbed his cutlass and with much splashing of blood ended the lives of his three children and his wife and himself. In all fourteen people were slaughtered in that house. Eleven murders and three suicides. And if you want to hold stubbornly to the epistemology that makes no allowance for spiritual dimensions, if you want to insist that this was merely a case of madness running in the family, then I might have asked you, months ago, to move into that house with your spouse and your two children. The community in Guyana knew better. They knew that this had something to do with evil, and with a world we cannot always see or smell or touch. I call it the devil, and the community knew he lived in that house which is why they insisted it not be destroyed – not because they wanted evil as their neighbour, but because at least it was contained. To destroy the house was to send the devil back into the world, like a roaring lion, seeking out whom he might devour. When I got there it was too late. The devil had been released.

I remember a tree in Jamaica that bore as its fruit, prophecies. That’s what it seemed like to me. The tree was in a dust bowl right outside of my high school and there must have been a man or woman who used charcoal to write words like “Repent” or “The Prime Minister must fall” or “Know ye this day who you shall serve” on squares of cardboard. These cardboard signs were hung up in the tree, and the branches had become overburdened with them, like a mango tree in season. Sometimes the wind would rattle these words, and the cardboards would hit against each other, such a strange and terrible sound, as if angels were crowded together, back to back, and were beating their wings.

I should I tell you about Queen Elizabeth II who came to Jamaica recently, and how in preparing for her arrival the government thought they should clean the city streets of litter, dog shit and dirt – and also of mad people. Maybe they thought they were being thorough because mad people were a combination of litter, dog shit and dirt. They rounded them up from around the city, put them in a truck and drove them miles and miles away, eventually dumping them by the edge of a poisonous lake, hoping, no doubt, that they would go for a swim and drown themselves. I do not know whether to prophesy with charcoal and cardboard the downfall of a government that could organize such a thing, or to praise the incredible distances that those women and men were able to walk, and the clear and precise sanity of their radars, so that one by one they found their way back to Kingston, in grand evening gowns of filth, ready to curtsy for the queen. Her royal highness’s arrival was greeted by another small scandal – a power-cut at the house of the Governor-General. It was not so much the power-cut that was scandalous, but that the generators failed to chip in. Still, many thought this was fair, because on that night the queen, like everyone else in Jamaica, had to eat her rice and peas in darkness.

I will end with a story that makes me sad even now. Earlier this year, I saw a friend who seemed almost unreasonably happy. I commented on his joy, his buoyancy, and he said it was true – he was putting himself in a good mood because he had to, because the day had been such a horrible one. He told me that he knew it was going to be a horrible day because he woke to the news, broadcast over the radio, of a family from an inner-city community who had been burnt out of their houses. My friend works with an agency that lends support to families who, by some misfortune, are suddenly without homes – so hearing the news that morning he was prepared for a hard day ahead. And yet, he wasn’t. The news he heard when he entered his office and I will tell you now – and also tell you that this slight correction of the details has not been broadcast on any radio station in Jamaica – has not been written in any newspaper, because this story is not newsworthy.

The family was not exactly a family. It was a house of four young men who the community suddenly suspected were gay. They gave them only an hour to leave – to grab whatever they could and then turn their backs on what had been their home. There interposes this sad and simple law of physics: they could only take with them what they could carry. In sixty minutes how can anyone take complete stock, how can anyone consider carefully and rationally the inventory of his life? An important certificate will be left hanging on the wall, a crucial receipt will be forgotten in a pants’ pocket, a fat envelope of money and a passport still in a drawer, incriminating evidence embarrassingly left under a mattress, life-saving tablets and a prescription still sitting on the night stand, a book of phone numbers on a table. How overwhelming it must be, the impulse to turn around, even to risk turning oneself into salt. Something that was left behind did bring one of the men back, and the community was waiting. They held him. They placed long rods of iron into the bonfire that had only recently been the house he lived in and then pressed these sizzling pieces of metal into his dark skin, burning through to pink soft mush, burning him until he collapsed. And though in this branding there were no actual words left on his ruined skin, every scar he now wears says: Faggot. Battyman. Sodomite. Leave!

If you ask me why I write stories, or novels, or poems, I would tell you it is because things that are real in my country, things that are factual, things that have happened and that continue to happen, have always had for me the quality of the unreal – the texture of fiction. This is what happens when you live in a country that is not the centre of the world; you become blessed with a kind of double vision. You see your life from the inside, and also from the outside – both locally and globally. You are conscious always of the reality of what you are living, and also the strange narrative of it. You become conscious of how this might be observed – sometimes unlovingly and without empathy – if you do not find a way to tell it right. In a way, this is how every writer the world over lives – this quality of being inside and outside at the same time – of living a life while floating above it, observing, taking notes. Often times I find there is no need to invent or to create. There is only the need to see, and then to tell.

IN DEFENCE OF MAAS JOE(2013)

Caribbean writing and Caribbean writers have come full circle – to the interesting place where we seem in danger of standing against many of the things we once stood for. For remember we are those whose project was once simple and noble: to challenge various centres of power. By writing in patois, we challenged orthodoxies of language; by writing about obeah or voodoo or in the mode of magic realism, we challenged orthodoxies of belief. Yes, that was us. Standing there on the outside, on the periphery as it were, we knew how to recognize and then challenge the dangerous cultural hegemonies of elite society. But to do that – to mount such a challenge – we had to privilege the folk and folk culture. We had to privilege people like Maas Joe and the story, perhaps, of his hapless donkey. And it’s true (of course it is true) that such stories became too easy too quickly for too many of us. It became easy, especially for our less ambitious writers. We who were against orthodoxies had inadvertently created our own – a Caribbean orthodoxy. And so, in the very spirit of what our literature has been, we had to turn around and challenge ourselves. It is therefore not the challenge that I query right now. That is as it should be. I wonder, though, about the fervency of it. These days I begin to wonder if the pendulum hasn’t swung too far; if our best writers are now too invested in writing about everyone else BUT Maas Joe and his rural life. We worry that we might be seen as trite and nostalgic. A new motto seems to hang over the desk of the modern Caribbean writer, a chant borrowed from rowdy political rallies that try to unseat incumbents: Maas Joe got to go.

The campaign against Maas Joe isn’t at all new. David Dabydeen wrote in 1990:

The pressure now is towards mimicry. Either you drop the epithet “black” and think of yourself as a “writer” (a few of us foolishly embrace this position, desirous of the status of “writing” and knowing that “black” is blighted) – that is, you cease dwelling on the nigger/tribal/ nationalistic theme, you cease folking up the literature, and you become “universal” – or else you perish in the backwater of small presses, you don’t get published by the “quality” presses, and you don’t receive the corresponding patronage of media-hype.1

And it isn’t confined to Caribbean literature. Avarind Adiga’s Booker Prize winning novel, The White Tiger, was praised almost rapturously by the Sunday Times. “Unlike almost any other Indian novel you might have read… this page-turner offers a completely bald, angry, unadorned portrait of the country as seen from the bottom of the heap; there’s not a sniff of saffron or a swirl of sari anywhere.” There is merit to both Adiga’s novel and this review, for what I think is being critiqued here is not “the folk” per se but the “folksiness” that often surrounds them. This reviewer is interested in a perspective from those at “the bottom of the heap” but seems worried that the overused tropes of Indianness (and perhaps, by extension, the tropes of any national identity) can become a limiting place in which the folk are too often trapped. It is true that those who don’t write their own stories – who become subjects of the writer’s imagination – are often made to live in a nostalgic and simplistic world rather than the more complicated grit of what would be their more realistic lives. The novel simplifies lives of course, but maybe some lives are more simplified than others. I agree wholeheartedly then that the citizens of the developing world ought to be allowed to live modern, urban, and even Western lives in fiction, but I disagree that only such lives are authentic, or that the so-called simple life cannot and has not been depicted in all its stunning complexity. Can we not allow the folk to hold an iPad in one hand, and a mango in the other?

The growing campaign against saffron, saris, mangoes, obeah and Maas Joe’s donkey, leads ultimately to our impoverishment. Recently I had to go to a fairly prominent high school in Jamaica to talk about literature and writing. I asked the students if they read Jamaican or Caribbean novels. A pall of silence fell on the group. One brave girl finally put up her hand and tried to explain. She hemmed and hawed, trying to get the words out. I think she knew that what she was about to say would be politically incorrect, but nonetheless it was her truth and indeed the truth of the class.

“Caribbean literature doesn’t really relate to us,” she said. “And you know… it’s like… I know people speak in patois and all of that, but you know, that’s not how I speak. And so all these books are written in patois and it’s like about slavery and all of that, and it’s like, I just can’t relate. You know what I mean?”

I have always found it a strange, and even a grossly unfair critique, to demand of fiction that it be real – that it be a direct reflection of our lives RIGHT NOW, that it have “literal” rather than “literary” merit. Did she really want a story about a middle-class girl in Jamaica, who lived in Cherry Gardens, and who spoke with a faux Californian accent? Such a story might reflect her life, but handled by a mediocre writer there is no reason to suppose it would be any better than the national literature she had already grown to dislike. She went on to explain that instead she liked reading young adult fantasy and science fiction from America. Clearly she wasn’t looking for representation. I suspect like most of us, she just wanted a damn good story. We relate to strong characters not because they share our specific biographies, but because they are convincingly written.

I felt for this girl. What she had said wasn’t posturing of any kind. She was being honest to what and how she felt. Yet, the terms she had chosen seemed wrong. Her disappointment, I think, was not in Caribbean literature, but in the examples of it she had encountered during school, books sterile enough to win the approval of the Ministry of Education, books so often plain and lacking in tension that they turn our students away from Caribbean literature rather than kindling their interest in it. I suspect her disappointment was in being forced to read yet another book by C. Everald Palmer (God rest his soul) or by Vic Reid (my father’s godfather, so a man for whom I have a soft spot), men who should most certainly be lauded, but who were so invested in writing appropriate national literature for school children, that their output lacked verve, that ability to evangelise and make converts out of their readers. Her disappointment was in an unimaginative and sometimes stale syllabus and in mediocre writers telling mediocre stories.

I tried to tell this student about the amazing Caribbean novels she was not allowing herself to read. Some of the best Caribbean novels – some in the canon like Erna Brodber’s Myal and Earl Lovelace’s The Wine of Astonishment, and newer books such as Shani Mootoo’s Valmiki’s Daughter or Kerry Young’s Pao – take place in small communities where people chew cane or eat mangoes, but where they come face to face with all the problems and complexities of modernity.

Mediocrity certainly does not lie in the setting of a village, or in the use of patois or in the subject matter of slavery. Mediocrity does not lie in saffron or in saris or in the person of Maas Joe or even in an exploration of his superstitions. And in the student’s declaration that she was simply over reading another Caribbean novel written in patois, and on the theme of slavery, she had actually forbidden herself from reading one of the single most ambitious and incredible books of Jamaican Literature in recent years – Marlon James’ The Book of Night Women.

Funnily enough, it was James who recently made dismissive mention of Maas Joe at a keynote presentation at the 2013 Bocas Festival in Trinidad and who therefore gives the present essay its occasion. On the dangers of creating a national literature, James jibed: