2,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Weyward Sisters Publishing

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Deutsch

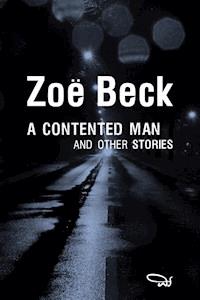

About this edition A man waiting in a tower to be killed by an Albanian sworn virgin as part of a blood vendetta. A mythical Irish puca who refuses to take no as a response to his presence. A man obsessed with a long-dead woman in an Impressionist painting. A boy haunted by what might have happened to a woman pulled dead from a lake. Everything is sharply observed and tightly woven, with a heavy dash of psychological suspense. The four stories in this mini collection create an undertow that the reader cannot escape. With an acute eye for both the phases of life and varying mental states, Zoë Beck has created an unforgettable array of compelling stories about people who find themselves enmeshed in situations beyond their control. In addition to her thrillers, Zoë Beck is an accomplished master of the short story, with her uncanny knack for compressing shifting interpersonal constellations into small prose jewels. Her cool, direct, unsentimental, and precise language makes Beck's unique contemporary twist on timeless themes all the more apparent.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 92

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2016

Ähnliche

About this edition

A man waiting in a tower to be killed by an Albanian sworn virgin as part of a blood vendetta. A mythical Irish puca who refuses to take no as a response to his presence. A man obsessed with a long-dead woman in an Impressionist painting. A boy haunted by what might have happened to a woman pulled dead from a lake.

Everything is sharply observed and tightly woven, with a heavy dash of psychological suspense. The four stories in this mini collection create an undertow that the reader cannot escape. With an acute eye for both the phases of life and varying mental states, Zoë Beck has created an unforgettable array of compelling stories about people who find themselves enmeshed in situations beyond their control.

In addition to her thrillers, Zoë Beck is an accomplished master of the short story, with her uncanny knack for compressing shifting interpersonal constellations into small prose jewels. Her cool, direct, unsentimental, and precise language makes Beck's unique contemporary twist on timeless themes all the more apparent.

About the author

Zoë Beck is a Berlin-based writer and translator. She co-directs with Jan Karsten the publishing company CulturBooks. Her next novel will be published in 2017 with Suhrkamp. Her awards include the following:

2010 Friedrich Glauser Prize for “Best Crime Short Fiction” 2014 Crime Prize from Radio Bremen, for Brixton Hill 2016 German Crime Fiction Prize, for Schwarzblende (Fade to Black)

About the translator

With degrees in art history and historic preservation, Rachel Hildebrandt worked as a historical consultant and editor before transitioning to literary translation. She has published both fiction and nonfiction works in translation, including Staying Human by Katharina Stegelmann (Skyhorse) and Herr Faustini Takes a Trip by Wolfgang Hermann (KBR Media). Rachel’s upcoming translations include Fade to Black by Zoë Beck (Weyward Sisters, Winter 2017) and Havarie by Merle Kroeger (Unnamed Press, Spring 2017).

A Contented Man by Zoë Beck

translated by Rachel Hildebrandt

and published by

First Edition

© by Zoë Beck

© for this compilation: Rachel Hildebrandt

Cover Design: Arne Kirschenberger

Cover Photo: Christopher Werth

Translation: Rachel Hildebrandt

Copy Editor: Pippa Goldschmidt

Layout: Dörte Karsten

Release Date: August 2016

ISBN 9783959880558

Contents

A Contented Man

Joachim Hartmann was a contented man. He had gone far in the profession he had dreamed of as long ago as his college days, and he had recently gotten married to a woman who was genuinely supportive of him. His wife Corinna had inherited a considerable fortune, and with this, they purchased one of the single-story, pastel-hued bungalows in Dreipfuhl Park which had been constructed for US officers back in 1956, the park itself being a Nazi-era creation. In keeping with the American suburban ideal, they placed a Porsche Cayenne for her and a Mercedes SLK for him in the driveway, and decided to no longer make do with being content, but to be truly happy.

In other words, Corinna decided this for both of them. She was no longer as young as she had once been, having reached the age of forty-six, and Joachim knew that every one of her previous relationships had ended on a traumatic note. He also knew that she had pinned all her hopes on him. Shortly after they met, he told her he had no plans to ever marry again. It was enough for him to have had this experience once in his lifetime. She had nodded in response, claiming she understood where he was coming from. Yet two years later, he found himself once again standing in the marriage license office, and he once again found that, in principle, it was all the same to him. If you’ve been married once, it’s easy enough to go through it a second time.

Besides that, there seemed to be a lot going for this marriage. For example, they had similar interests: He worked as a drama critic for the arts page of a large daily newspaper, and she was the state director for cultural events in the capital. This meant that both privately and professionally there were always sufficient conversation topics and points of intersection. Recently he had been awarded a fairly prestigious cultural prize, and thanks to Corinna, half of Berlin’s political who’s who had come to the ceremony. Moreover, Corinna was too old to want children, which might have been a problem with a younger woman. Furthermore, he valued her quiet, intellectual ways. And since they both had solid financial support behind them, they could pursue a relaxed, fully equal partnership. Thus, Corinna was happy, and Joachim was content. Until he caught sight of the girl from the Renoir painting in the flesh.

This was the day he met up with his friend Robert, a choreographer with the Berlin State Ballet. Joachim enjoyed watching the rehearsals, though not when the dancers were still working on the practice stage. But as soon as they were up on the main stage, he would sit in the dark auditorium and simply watch. Admiring the highly trained, supple bodies, the sculpted muscles that did not carry a single gram of fat, the graceful movements through which the bodies were transformed into machines, seemingly capable of anything. At such moments, Joachim did not think about the people he was observing up there, only about the figures they were portraying, the music they were giving shape to.

Everything changed that day when he caught sight of the girl. She looked exactly as she had for the twenty-five years he had been studying her: reddish gold hair, wide blue eyes, and a silent longing in her gaze. He saw her poised in a battement tendu, and for the first time ever, one of the figures on the stage became an actual person. The Renoir painting had stepped out of its frame and was dancing for him.

Since his college days, a print of Renoir’s Danseuse had hung in every one of his apartments. Even in his new house in Dreipfuhl Park, it was hanging in his study above the desk. It had taken four weeks until he was finally able to put it up. The previous print had not survived the move, and the delivery of the new one had taken an unbelievably long time. At first, there had been a mix-up, and someone had sent him a kitschy Klimt picture. Then there had been some complications with the delivery itself, and after that, the print had been mailed to the wrong address. Four weeks without his Danseuse - his wife had laughed at him because he was so fixated on his picture. But when it finally arrived, she had seen his face - his eyes as they glided, warm and content, over the young, pale figure - and she had never laughed at him again.

He had kept this girl in his sight since college. She had never changed, never moved, only ever gazing slightly past him with her large blue eyes. But today she was dancing before him.

His friend Robert woke him out of a state that was somewhere between daydream and shock. The dancers had long vanished from the stage. Robert didn’t pick up on what was going on with him. He just thought his friend was lost in thought, because he was working too much these days. Joachim’s wife also didn’t notice a thing. Or to be more precise, he tried his best to make sure that there was nothing for her to notice, and his effort succeeded. During the day, when she would disappear into her office, he would steal over to Robert’s rehearsals. He never stayed longer than half an hour, and even managed to evade Robert’s attention altogether. Since he was known in the theater, he had no problems gaining access, and that was why nobody really saw him. He made sure his work never suffered from this distraction that the girl had now created for him. Quite the contrary, he worked harder than ever and reached unprecedented heights in the estimation of the editorial staff.

However, after a week passed, this no longer functioned. He knew that thirty minutes wasn’t enough for him anymore. But it also made no sense for him to sit for a longer period of time in the dark auditorium, watching her. He needed to talk to her.

He told Robert that he was planning to write a feature article about the performance. To prepare for that, he wanted to talk to the solo dancer, whose great talent he intended to highlight in the article. Robert was more than willing to introduce him to her. What more could he wish for than a feature article about his performance? He failed to catch the way his friend’s eyes glided across the dancer’s body.

Up close, the girl did not look as young as she did in the painting, much to Joachim’s relief. She was in her early twenties, and her name was Helene. She agreed to his invitation to interview her over a meal. He detected friendliness in her eyes, but her gaze brushed just slightly past him. And that was the way it was over dinner as well. The only thing she touched were a few lettuce leaves and a glass of table water. She would never look at him directly, just like the girl in the picture.

After their meal, he was unable to fall asleep that night. He tossed and turned, and wondered what he would have to do to finally make her look at him. It might take some time, and in order to gain this time, he decided not to publish his interview with her in the newspaper. Not yet anyway, as he told her, because he had something else in mind than to just introduce her in the context of her role as the solo dancer in the upcoming premiere. He wanted to write something bigger about her, a photo reportage, or perhaps even something televised, since he had excellent contacts in that world. She didn’t say a word as he rambled on about this, remaining silent and looking just slightly past him, although she smiled.

From this point on, he hardly left her side. He materialized when she went to morning warm-up and attended all of her rehearsals. He sat next to her when she nibbled on the little food permitted to her, in order to avoid weight gain. The only times he left her in peace were the hours she spent with her therapist. He admired her slender, sculpted muscles, and loved it when she wore her workout clothes inside out so the seams wouldn’t bother her. He found it exciting when she practiced the love scenes with her dance partner, and felt pity when she tried to hide her painkillers from the others. He listened when she explained that even as a child, she had had only one ambition: to dance. She had overcome the resistance of her parents, who owned a farm in Vorpommern, and the Berlin State Ballet had always been her greatest dream.