17,37 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: WS

- Kategorie: Religion und Spiritualität

- Sprache: Englisch

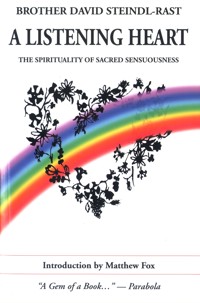

In this book, Brother David Steindl-Rast, who has been a monk for more than 50 years, argues that every sensual experience—whether the joy of walking barefoot or the fragrance of the season—should be recognized as a spiritual one.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 183

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

A LISTENING HEART

Brother David Steindl-Rast

Newly Revised

A Crossroad Book

The Crossroad Publishing Company

New York

This printing: March 2016

The Crossroad Publishing Company

www.CrossroadPublishing.com

Copyright © 1983, 1999 by David Steindl-Rast

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the written permission of The Crossroad Publishing Company.

Printed in the United States of America

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Steindl-Rast, David.

A listening heart : the spirituality of sacred sensuousness / David Steindl-Rast. — [Rev. ed.] p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 0-8245-1780-6 (pbk.)

1. Spiritual life — Catholic Church. 2. Sensuality —

Religious aspects — Catholic Church. I. Title.

BX2350.65.S75 1999

248.4'82 — dc21 99-34367

CIP

The Publisher gratefully acknowledges permission to use the following copyrighted material:

“The Environment as Guru” originally appeared in Cross Currents, vol. 24 nos. 2-3 (1973). Used with permission.

“A Deep Bow” originally appeared in Main Currents XXIII, no. 5 (1967). Used with permission. Excerpts from Four Quartets by T. S. Eliot reprinted by permission of Faber and Faber Ltd.

Excerpts from Four Quartets by T. S. Eliot reprinted by permission of Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, Inc.; Copyright © 1943 by T. S. Eliot, renewed 1971 by Esme Valerie Eliot.

Excerpts from Candles in Babylon. Copyright © 1982 by Denise Levertov. Reprinted by permission of New Directions Publishing Corp.

Excerpts from Candles In Babylon by Denise Levertov. Reprinted by permission of Laurence Pollinger Unlimited.

“Haiku” from An Introduction to Haiku by Harold G. Henderson. Copyright © 1958 by Harold G. Henderson. Reprinted by permission of Doubleday & Company, Inc.

Excerpts from Duino Elegies by Rainer Maria Rilke. Translated by J.B. Leishman/Stephen Spender. Translation copyright 1939 by W.W. Norton & Company, Inc., renewed © 1967 by Stephen Spender and J.B. Leishman. Reprinted by permission of W.W. Norton & Company Inc.

Excerpts from Collected Poems 1909-1962 by T. S. Eliot reprinted by permission of Harcourt, Brace & World, Inc. Copyright © 1963.

Excerpts from Collected Poems 1909-1962 by T.S. Eliot reprinted by permission of Faber and Faber Ltd.

Excerpts from Samtiche Werke Vol. I by R. M. Rilke reprinted by permission of Frankfurt: Insel-Verlag: Copyright © 1962.

Excerpts from Woods by Noelle Oxenhandler reprinted with permission of the author.

“The Guitarist Tunes Up” from On a Calm Shore by Frances Cornford. Copyright ©1921 by Frances Cornford. Reprinted by permission of the Cresset Press.

May this new version of A Listening Heart be a token of my gratitude for the listening hearts of friends, especially

NANCY L. GRAEFF

and all others who helped with professional skill, advice, support, and constructive criticism.*

I am deeply grateful also for the listening hearts of my readers.

* Snjezana Bakula, Mel Bricker, Joan Casey, Michael Casey, Lorilott Clark, Brendan Collins, Sandy Conheim, Judy Dunbar, Christine Gunn, Gwendolyn Herder, Kateri Kautai, Paul Kobelski, Paul Lacey, Matthew Laughlin, Chris Lorenc, Laura Martin, Sajid Martin, David Schulz, Michaela Terrio, Daniel Uvanovic, Margaret van Kempen O.S.B.

Contents

Introduction

Not a Foreword

A Listening Heart

The Environment as Guru

Sacred Sensuousness

Sensuous Asceticism

Mirror of the Heart

A Deep Bow

Introduction

Brother David Steindl-Rast is an authentic monk. Like the Buddhist monk Thich Nhat Hanh, whom he cites in this book, Brother David is able to communicate simple living and simple seeing to the rest of us who are in the world looking for meaning and spiritual support as we struggle to pay our bills, raise our families, face our trials, fight our ethical battles and just plain live.

What makes an authentic monk? I think clarity of mind and sight, simplicity of life and gratitude in the heart. In short, what Brother David calls a “listening heart.”

It takes self-knowledge and freedom from projection to render the heart a listening one. The monk listens. All of us do (or ought to). The monk might be called a professional listener. Maybe we all should be professional listeners.

For there is so much that is being said in the universe and in our hearts that deserves silent attention — some of it is the music of beauty and awe and wonder; and some of it is the lamentation of grief and anger, sadness and sorrow. All of it deserves our listening. And Brother David in this book gives us ample lessons in how to enrich our listening.

At this time of an emerging millennium (and an ending one), when the planet is being despoiled by so much reckless human encroachment of its natural systems of checks and balances, and in this time when Christianity seeks to simplify itself and to return to the spirit of Jesus and the Christ-awareness that Jesus knew so well, certain monks are being asked to share the fruits of their listening heart with others. Thich Nhat Hanh, the Dalai Lama and Pema Chodron are examples of persons responding to this call from the East; Brother David is a fine example from the West. Indeed, these people are on similar paths. Though their journeys started differently — three with the Buddha, Brother David with Christ — their paths have crossed. Intersection is happening a lot these days. The young recognize it. Cultural pluralism and religious pluralism and spiritual pluralism are signs of our times. And Brother David is a leader in this work of spiritual ecumenism and of science reconnecting to spirituality and of rescuing the essence of the Christian message, what Meister Eckhart called “the kernel,” from the historical Jesus and from his monastic tradition and practices.

In this book we readers are the grateful and fortunate recipients of Brother David’s wisdom. Brother David walks his talk and he sings his silence. Like his Benedictine Sister Hildegard of Bingen, whose 900th anniversary we celebrate this year, he seeks wisdom over knowledge and in preference to folly and he makes our hearts greener and wetter and more creative and joyful.

Time and again Brother David returns to the key theme of gratitude in this book. He is so wise to do so. If our species were truly grateful, would we be despoiling the very beauty and health of this planet as we are? Or would we be so often seduced by luxury life-styles or consumer addictions if we had learned what the realgraces in life are? (“Grace” and “gratitude” come from the very same root word.) With Meister Eckhart, Brother David’s message could be summarized as follows: If the only prayer you say in your whole life is “Thank You,” that would suffice.

Brother David knows his Benedictine tradition well and knows it was based on a Biblical, original blessing theology more than an original sin ideology. In this book he instructs us in a holy and sensuous asceticism that does not flee the body or the body politic but inspires both. This book breathes spirit and life into persons and community.

When he declares that “every sensuous experience is at heart a spiritual one: a divine revelation,” Brother David calls us to our senses again. Our holy senses. He calls us to the very basic meaning of mysticism, to “enter the mysteries,” and he demonstrates how our senses are indeed gateways to Spirit and not obstacles to Spirit as some guilt-producing theologians have suggested they were over the centuries. Brother David redefines “asceticism,” insisting that an authentically Incarnational Christian theology ought to speak of “sensuous asceticism.” This represents a giant step forward since during the mechanistic modern era the term “asceticism” pretty much degenerated into a kind of mechanical way of treating and indeed abusing our senses for the sake of a perceived spiritual purity. Our senses are meant to serve the heart — “our ears hear, but only a listening heart understands.” Yet we are meant to go beyond sensual pleasure to a joy that lasts.

I am grateful for this deep and profound book, as I am sure many other readers will be also. It tells truths of the spiritual life that need telling and it tells them with story and poems and humor — a style that deserves our attention. The author speaks not from the lofty pinnacles of a pulpit preacher or an academic savant, but from the inside to the inside, that is from listening heart to listening heart. To get the most from this book one must listen with one’s heart.

I hope we are listening — young and old alike. For the future of our species and of the planet’s beauty and health and diversity as we know it depends on what we humans choose to do with our hearts. If we can let go and cleanse our hearts, learning to listen deeply again, then there is hope. To listen with gratitude, and grow in the reverence and wonder that grows from gratitude, and grow in our capacities for not-taking-for-granted. In this sense, Brother David invites all of us to be mystics again and prophets, too, that our joy may flow over into our work in the world. In this way, not only Eastern and Western wisdom, theological and scientific knowledge, but also the monastic and lay worlds may melt together so that all may be one and in this great “one-ing” we may together recover community and celebration, justicemaking and healing. This would surely be a blessing and return us to a sense of original blessing. A time of true community celebration and gratitude would follow. Reverence for all being would be the result. And still more of creation would join the celebration.

Matthew Fox

University of Creation Spirituality

Oakland, California

Not a Foreword

Dear Casual Browser,

This is NOT A FOREWORD, just a brief note to you. Writing a book is a chore; finishing it is gratifying; seeing it published is a joy. Now imagine what joy it is for me that sixteen years after it first came out, A Listening Heart is still finding a steady stream of readers. Better still: readers tell me they find this teenager of mine a helpful kid. This pleases a parent, I readily admit. Less readily, I must admit that this offspring of mine was not the result of Planned Parenthood. In fact, at first sight I didn’t even recognize my baby.

As it happened, I had just returned from a long lecture tour down under when, after a lecture back home again, someone handed me a book to sign. Noting my surprised look, she explained, “You wrote it!”

Did I? Well, in a sense I did — not as a book, though. A well-meaning friend had put together essays of mine and turned them into this book. While grateful, I was also embarrassed. A “listening heart” is indeed a key topic for me, but the essays didn’t all fit this theme equally well, nor did they develop it consistently. So, when I was asked to prepare a German translation, I replaced the middle section with new chapters. In this revised edition, I have done the same for English readers. Now I am satisfied — as satisfied as a dyed-in-the-wool perfectionist can be.

Nothing essential to the topic was lost; much, I feel, was gained. The two eliminated chapters on contemplative life and community were too sketchy. I hope to expand them into a separate book. Instead I am offering here something fresh: a Christian spirituality that celebrates sensuous pleasure and a spiritual practice to match it.

A spirituality based on original blessing (as opposed to one fixated on original sin) has been making promising noises lately, like a fiery stallion whinnying and pawing the ground. This new version of A Listening Heart invites you to get in the saddle of that life-affirming spirituality and gallop away.

A Listening Heart

The key word of the spiritual discipline I follow is “listening.” This means a special kind of listening, a listening with one’s heart. To listen in that way is central to the monastic tradition in which I stand. The very first word of the Rule of St. Benedict is “Listen!” — “Ausculta!” — and all the rest of Benedictine discipline grows out of this one initial gesture of wholehearted listening, as a sunflower grows from its seed.

Benedictine spirituality in turn is rooted in the broader and more ancient tradition of the Bible. But here, too, the concept of listening is central. In the biblical vision all things are brought into existence by God’s creative Word; all of history is a dialogue with God, who speaks to the human heart. The Bible has been admired for proclaiming with great clarity that God is One and Transcendent. Yet, the still more admirable insight of the religious genius reflected in biblical literature is the insight that God speaks. The transcendent God communicates Self through nature and through history. The human heart is called to listen and to respond.

Responsive listening is the form the Bible gives to our basic religious quest as human beings. This is the quest for a full human life, for happiness. It is the quest for meaning, for our happiness hinges not on good luck: it hinges on peace of heart. Even in the midst of what we call bad luck, even in the midst of pain and suffering, we can find peace of heart, if we find meaning in it all. Biblical tradition points the way by proclaiming that God speaks to us in and through even the most troublesome predicaments. By listening deeply to the message of any given moment I shall be able to tap the very Source of Meaning and to realize the unfolding meaning of my life.

To listen in this way means to listen with one’s heart, with one’s whole being. The heart stands for that center of our being at which we are truly “together.” Together with ourselves, not split up into intellect, will, emotions, into mind and body. Together with all other creatures, for the heart is that realm where I am paradoxically not only most intimately myself, but most intimately united with all. Together with God, the source of life, the life of my life, welling up in my heart. In order to listen with my heart, I must return again and again to my heart through a process of centering, through taking things to heart. Listening with my heart I will find meaning. For just as the eye perceives light and the ear sound, the heart is the organ for meaning.

The most original insight of the Bible is that “God speaks” to us through nature and history.

The daily discipline of listening and responding to meaning is called obedience. This concept of obedience is far more comprehensive than the narrow notion of obedience as doing-what-you-are-told-to-do. Obedience in the full sense is the process of attuning the heart to the simple call contained in the complexity of a given situation. The only alternative is absurdity. Ab-surdus literally means absolutely deaf. If I call a situation absurd I admit that I am deaf to its meaning. I admit implicitly that I must become ob-audiens — thoroughly listening, obedient. I must give my ear, give myself, so fully to the word that reaches me that it will send me. Being sent by the word, I will be obedient to my mission. Thus, by doing the truth lovingly, not by analyzing it, I will begin to understand.

The ethical implications of all this are obvious. Therefore it is all the more important to remember that we are not primarily concerned with an ethical but with a religious matter; not primarily with purpose, even the most exalted purpose of good works, but with that religious dimension from which every purpose must derive its meaning. The Bible calls the responsive listening of obedience “living by the Word of God,” and that means far more than merely doing God’s will. It means being nourished by God’s word as food and drink, God’s word in every person, every thing, every event.

This is a daily task, a moment by moment discipline. I eat a tangerine and the resistance of the rind, as I peel it, speaks to me, if I am alert enough. Its texture, its fragrance speak an untranslatable language, which I have to learn. Beyond the awareness that each little segment has its own degree of sweetness (the ones on the side that was exposed to the sun are the sweetest) lies the awareness that all this is pure gift. Or could one ever deserve such food?

I hold a friend’s hand in mine, and this gesture becomes a word, the meaning of which goes far beyond words. It makes demands on me. It is an implicit pledge. It calls for faithfulness and for sacrifice. But it is above all a celebration of friendship, a meaningful gesture that need not be justified by any practical purpose. It is as superfluous as a sonnet or a string quartet, as superfluous as all the ultimately important things in life. It is a word of God by which I live.

But a calamity is also a word of God when it hits me. While working for me, a young man, as dear to me as my own little brother, has an accident. Glass is shattered in his eyes, and I find him lying blindfolded in a hospital bed. What is God saying now? Together we grope, grapple, listen, strain to hear. Is this, too, a life-giving word? When we can no longer make sense of a given situation, we have reached the crucial point. Now arises the challenge that calls for faith.

The clue lies in the fact that any given moment confronts us with a given reality. But if it is given, it is gift. If it is gift, the appropriate response is thanksgiving. Yet, thanksgiving, where it is genuine, does not primarily look at the gift and express appreciation; it looks at the giver and expresses trust. The courageous confidence that trusts in the Giver of all gifts is faith. To give thanks even when we cannot see the goodness of the Giver — to learn this is to find the path to peace of heart. For happiness is not what makes us grateful. It is gratefulness that makes us happy.

In a lifelong process the discipline of listening teaches us to live by every word that proceeds from the mouth of God without discrimination. We learn this by “giving thanks in all things.” The monastery is an environment set up to facilitate just that. The method is detachment. When we fail to distinguish between wants and needs we lose sight of our goal. Our needs (many of them imaginary) keep increasing; our gratefulness (and so our happiness) dwindles. Monastic discipline reverses this course. The monk strives for needing less and less while becoming more and more grateful.

Our heart is that center where we are one with ourselves, with all others, and with God.

Detachment decreases our needs. The less we have, the easier it is gratefully to appreciate what we do have. Silence creates the atmosphere for detachment. Silence pervades monastic life in the same way in which noise pervades life elsewhere. Silence creates space around things, persons, and events. Silence singles them out and allows us gratefully to consider them one by one in their uniqueness. Leisure is the discipline of finding time to do so. Leisure is the expression of detachment with regard to time. For the leisure of monks is not the privilege of those who can afford to take time; it is the virtue of those who give to everything they do the time it deserves to take.

Within the monastery the listening which is the essence of this spiritual discipline expresses itself in bringing life into harmony with the cosmic rhythm of seasons and hours, with “time, not our time” as T. S. Eliot calls it. But in my personal life, obedience often demands that I serve outside the monastery. What counts is the listening to the soundless bell of “time, not our time,” wherever it be and the doing of whatever needs to be done when it is time — “now, and in the hour of our death.” “And the time of death is every moment,” says T. S. Eliot, because the moment in which we truly listen is “a moment in and out of time.”

One method for entering moment by moment into that mystery is the discipline of the Jesus Prayer, the Prayer of the Heart, as it is also called. It consists basically in the mantric repetition of the name of Jesus, synchronized with one’s breath and heartbeat. When I repeat the name of Jesus at a given moment in time, I make that moment transparent to the Now that does not pass away. The whole biblical notion of living by the Word is summed up in the name of Jesus in whom I as a Christian adore the Word incarnate. By giving that name to every thing and to every person I encounter, by invoking it in every situation in which I find myself, I remind myself that everything is just another way of spelling out the inexhaustible fullness of the one eternal word of God, the Logos; I remind my heart to listen! This image might seem to suggest a dualistic rift between God who speaks and the obedient heart. Yet, the dualistic tension is caught up and transcended in the mystery of the Trinity. In the light of that mystery I understand myself as a word spoken out of the Creator’s heart and at the same time addressed by the Creator. But the communion goes deeper. In order to understand the word addressed to me, the word I am, I must speak the language of the One who calls. If I can understand God at all this can come about only by my sharing in God’s own Spirit of Self-understanding. Thus the responsive listening in which my spiritual discipline consists is not dualistic communication.