Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Icon Books

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

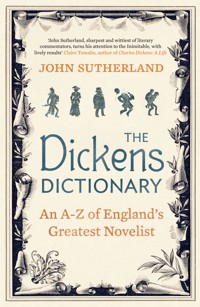

'Wonderful...concise, witty, effortlessly learned.' Sunday Times How does Magwitch swim to shore with a great iron on his leg? Where does Fanny Hill keep her contraceptives? Whose side is Hawkeye on? And how does Clarissa Dalloway get home so quickly? In this new edition sequel to the enormously successful Is Heathcliff a Murderer?, John Sutherland plays literary detective and investigates 32 literary conundrums, ranging from Daniel Defoe to Virginia Woolf. As in its universally loved predecessor, the questions and answers are ingenious and convincing, and return the reader with new respect to the great novels that inspire them.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 348

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Praise for earlier editions ofCan Jane Eyre be Happy?

‘A wonderful book, concise, witty, effortlessly learned’

Sunday Times

‘Another gloriously erudite compilation of puzzles in classical fiction’

The Times

CAN JANE EYRE BE HAPPY?

More Puzzles in Classic Fiction

JOHN SUTHERLAND

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

In 1983 I found myself in a very lucky place. I had landed a job at an American university routinely judged the best in the world at what it does – Caltech (the California Institute of Technology). What it does, pre-eminently, is science – Caltech was instrumental, for example, in putting that robotic hound, Rover, on Mars.

Caltech’s founder, George Ellery Hale, believed that you could not be a pre-eminent scientist without a grounding in the Humanities. That meant, inter alia, being on nodding terms with great literature. I very much concurred with Hale’s belief, although the young rocket scientists to whom I taught Jane Austen sometimes voiced their doubts, desperate as they were to get back to vector analysis or whatever. But they wanted their 4.1 Grade Point Averages and worked like beavers (Caltech’s dam-building animal mascot).

I had a light teaching load. The Institute’s only requirement was that I devote myself to research, in my field. I was surrounded by libraries containing the best collections of Victorian fiction anywhere. Primarily the Henry E. Huntington Library (Hale had been instrumental in creating that institution as well). A fellow Victorianist once told me: ‘If I died and went to heaven it would be the Huntington to the gentle accompaniment of harp music.’ I agreed.

My love affair with Victorian fiction – more properly nineteenth-century fiction, from Regency to Edwardian, Walter Scott to Mrs Humphry Ward – had begun in childhood: at that point in one’s early life when ‘stories’ are a door to other worlds. One’s Narnia.

I was born in 1938 – only 37 years after Victoria’s death. There was a lot of Victorian England still standing around me, as I grew up, in a working-class area of Colchester. A hundred yards away, across the Wellington Street (good Victorian name) bomb site, was a blacksmith’s, still shoeing the horses which pulled milk and coal vans. I’ve always believed that you could never fully understand Great Expectations – centred as it is on Joe’s smithy – unless you have smelled that sharp, hot fire and seen red-hot horseshoes being hammered on the anvil. Something that permeates the novel’s first hundred pages.

The first adult novel I recall reading is George Du Maurier’s Peter Ibbetson, illustrated by the writer-artist himself (a rare ambidexterity in Victorian fiction – only Thackeray is Du Maurier’s equal). Du Maurier’s story imagines nocturnal time travel into your own past, which, like a ghost, you can observe but never change (scholars routinely make comparisons with Proust). The trick, which Ibbetson discovers, is to ‘sleep true’, contorting your arms in ways the narrative transcribes. I woke up myself many mornings stiff as a board from, hopelessly alas, sleeping true. Thence, through Sheba’s Breasts, to Rider Haggard. I was addicted.

Leap forward to 1983 and California. I conceived the Quixotic mission of reading every Victorian novel there was. Of course, I never finished the course. To be honest I came down at the academic equivalent of Becher’s Brook – the first fence. But I can honestly claim to have read, over the next ten years (the most enjoyable decade, intellectually, of my academic career) some 4,000 titles. The total number in the genre is, I calculate, around 50,000, depending where you place the definitional margins.

What to do with that mass I had read? I compiled an encyclopaedia – published as the Longman Companion to Victorian Fiction. My relationship with the Victorian has always been companionable.

Why, though, had I read all these novels, the bulk of which canonical literary history had cast into oblivion? What, put another way, had I got out of them? Pile them one on the other and they would over-top Mount Wilson, the noble mountain I could see every day from my Pasadena office window.

Why read so many? The answer was simple. Because I enjoyed them. It was as simple as that. In the course of my career I went on to edit many Victorian novels (sixteen Trollopes was my highest score) for reprint series – Oxford World’s Classics, Penguin Classics, Everyman Classics, Broadview Classics. It involved introductions, textual curating and, most challengingly, annotation. Explaining the difficult bits.

That last was what I most relished. There were so many small things, if one read closely, which were ‘puzzling’.

For example: in Hardy’s The Mayor of Casterbridge the hero, Michael Henchard, is brought low, as mayor and magistrate, by the furmity seller (and what, precisely, is furmity?) who has been charged with a ‘public nuisance’, urinating in the street late at nights. But in what ‘public convenience’ could she have relieved her old, drink-distended, bladder? Dorchester, ‘Casterbridge’, would have had just one convenience, for men, at the newly opened railway station.

To continue this interestingly improper line of thought, is Daniel Deronda, who discovers himself in adult life to be Jewish, circumcised? If so, has he never wondered about the fact?

How does Magwitch, in Great Expectations, swim to shore from the offshore prison hulk (what, incidentally, were they?) where he has been incarcerated, with a huge iron manacle round his ankle? He would, surely, ‘sleep with the fishes’, as the mafia say. Is it an error on Dickens’s part – or is there a subtle explanation one has missed?

If Dracula bites you, you are vampirised. How long, I asked my Caltech students, all of them maths whizzes, would it be before the human race were all ‘turned’, doomed themselves to extinction by blood starvation? Why does Dracula choose to come to England in the first place? Are there not throats enough for him in Transylvania?

Griffin’s first experiment, in Wells’s The Invisible Man, is to turn a piece of cloth invisible. Why then does he choose to walk down Oxford Street cold and naked and not make himself an invisible suit?

Literary criticism, at the period when I was pondering this higher trivia, was subjecting itself to a peculiarly earnest ‘theoretical’ orthodoxy. What I was doing, as higher-minded colleagues gently reminded me, was childish.

But that, it seemed to me, was the point. The essential reason I loved Victorian fiction was because it still gave me primal pleasures I had first found in it as a child.

I am, among my other qualifications, a Junior Leader – trained to teach narrative to (American) pre-school and kindergarten children. One of the things I learned with my infant charges was that, when discussing a story, you should never ask them things you know but things you’ve never quite been sure about.

Why, for example, does Jack go up the beanstalk the second time? Why is Red-Riding-Hood’s grandmother living by herself in a wolf-infested forest, bed-bound and without, apparently, any way of feeding herself? Not, exactly, social care.

Such imponderables were closely related to how I read the Victorian novel. A swarm of question marks has always seemed to me to hover over the genre.

I managed to interest a publisher, OUP, in a collection of puzzle essays under the quizzical title, Is Heathcliff a Murderer? The book proved surprisingly successful. This (the 1990s) was the period when the reading of literature, at the ground level, was being re-energised by reading groups and literary festivals. A groundswell. A gratifying volume of private correspondence from readers was sent me about the puzzles I raised – much of it better informed on some topic than I was. A knowledgeable lawyer informed me why Fagin is hanged (he hasn’t, you’ll recall, murdered anyone). A dentist informed me what Heathcliff meant, precisely, when he described himself as suffering from a ‘moral teething’.

Astonishingly (to me, at least) Is Heathcliff a Murderer? made the Sunday Times bestseller list. More flattering were Jasper Fforde’s Victorian fiction fantasias, beginning with The Eyre Affair (2001). Fforde’s wildly imaginative fictions courteously acknowledged my influence. How rarely can literary critics claim to have influenced what they aspire to criticize.

I went on to write other puzzle books, of which this is the second. I very much enjoyed writing it. I hope you enjoy reading it.

J.S.

A NOTE ON THE TEXTS

One of the great breakthroughs in the reading and study of Victorian fiction has been its new accessibility. I am thinking, principally, of the Project Gutenberg library.

The project was the life’s mission of Michael S. Hart (1947–2011). Recruiting an army of volunteer editor/transcribers, Project Gutenberg.org has made available, at a few key strokes away, thousands of literary titles and a vast mass of Victorian fiction. It is currently adding 50 new e-books a week. The material is available in a variety of differently paginated formats – most pleasing to the eye is ‘epub’, easily adaptable to the tablet app, iBooks (references in the text that follows are, necessarily, to chapters). All the Gutenberg texts are searchable by keyword.

As a grateful acknowledgement to Hart’s donation to lovers of Victorian fiction, and his enlargement of the field, I have used Gutenberg texts throughout in this book. In this respect, as well as in some corrections and updates, the text here differs from that originally published by Oxford University Press in 1997.

Daniel Defoe Robinson Crusoe

Why the ‘Single Print of a Foot’?

J. Donald Crowley is amusingly exasperated about Defoe’s many narrative delinquencies in Robinson Crusoe. ‘Perhaps the most glaring lapse’, Crowley says in his Oxford World’s Classics edition of the novel,

occurs when Defoe, having announced that Crusoe had pulled off all his clothes to swim out to the shipwreck, has him stuff his pockets with biscuit some twenty lines later. Likewise, for the purpose of creating a realistic effect, he arranges for Crusoe to give up tallying his daily journal because his ink supply is dangerously low; but there is ink aplenty, when, almost twenty-seven years later, Crusoe wants to draw up a contract … Having tried to suggest that Crusoe suffers hardship because he lacks salt, he later grants Crusoe the salt in order to illustrate his patient efforts to teach Friday to eat salted meat. Crusoe pens a kid identified as a young male only to have it turn into a female when he hits upon the notion of breeding more of the animals. (p. xiii)

Such inconsistencies convince Crowley that ‘Defoe wrote too hastily to control his materials completely’. His was a careless genius.

Haste and carelessness could well account for some baffling features in the famous ‘discovery of the footprint’ scene. It occurs fifteen years into Robinson’s occupation of his now thoroughly colonized and (as he fondly thinks) desert island. At this belated point the hero is made to describe his outdoor garb. He has long since worn out the European clothes which survived the wreck. Now his coverings are home-made:

I had a short jacket of goat’s skin, the skirts coming down to about the middle of my thighs; and a pair of open-kneed breeches of the same; the breeches were made of a skin of an old he-goat, whose hair hung down such a length on either side, that, like pantaloons, it reached to the middle of my legs. Stockings and shoes I had none; but I had made me a pair of something, I scarce knew what to call them, like buskins, to flap over my legs, and lace on either side like spatterdashes; but of a most barbarous shape, as indeed were all the rest of my clothes.*

This sartorial inventory has been gratefully seized on by the novel’s many illustrators, from 1719 onwards (see Fig. 1). The salient feature is that Robinson goes barefoot. And it is to rivet this detail (‘shoes I had none’) in our mind that at this point Defoe describes Crusoe’s wardrobe. In the preceding narrative, if it crosses the reader’s mind, we assume that Crusoe has some protection for the soles of his feet (the island is a rough place).

Figure 1. Frontispiece from the first edition, 1719

Oddly, Robinson seems not to have taken a supply of footwear from the ship’s store nor any cobbling materials with which to make laced moccasins from goatskin. Shortly after being marooned he found ‘two shoes’ washed up on the strand, but they ‘were not fellows’, and were of no use to him. Much later, during his ‘last year on the island’, Robinson scavenges a couple of pairs of shoes from the bodies of drowned sailors in the wreck of the Spanish boat. But, when he sees the naked footprint on the sand, Crusoe is barefoot.

The footprint is epochal, ‘a new scene of my life’, as Crusoe calls it. He has several habitations on the island (his ‘estate’, as he likes to think it) and the discovery comes as he walks from one of his inland residences to the place on the shore where he has beached his ‘boat’ (in fact, a primitive canoe):

It happened one day about noon, going towards my boat, I was exceedingly surprised with the print of a man’s naked foot on the shore, which was very plain to be seen in the sand: I stood like one thunder-struck, or as if I had seen an apparition; I listened, I looked round me, I could hear nothing, nor see any thing; I went up to a rising ground to look farther: I went up the shore, and down the shore, but it was all one, I could see no other impression but that one; I went to it again to see if there were any more, and to observe if it might not be my fancy; but there was no room for that, for there was exactly the very print of a foot, toes, heel, and every part of a foot; how it came thither I knew not, nor could in the least imagine.

Two big questions hang over this episode. The first, most urgent for Robinson, is ‘Who made this footprint?’ The second, most perplexing for the reader, is ‘Why is there only one footprint?’ In the above passage, and later, Crusoe is emphatic on the point. Was the single footprint made by some monstrous hopping cannibal? Perhaps Long John Silver passed by, from Treasure Island, with just the one foot and a peg leg? Has someone played a prank on Robinson Crusoe by raking over the sand as one does in a long-jump pit, leaving just the one ominous mark? More seriously, one might surmise that the ground is stony with only a few patches of sand between to receive an occasional footprint. This is the interpretation of G.H. Thomas in the next version of this scene (see Fig. 2; note the shoes II†). The objection to the thesis of this illustration is that Crusoe would scarcely choose such a rocky inlet as a convenient place to beach his boat.

Robinson has no time for investigation of the footprint. He retreats in hurried panic to his ‘castle’, not emerging for three days. Is it the mark of the Devil, he wonders, as he cowers inside his dark cave? That would explain the supernatural singularity of the footprint, since the devil can fly. In his fever vision, years before, Robinson saw the Evil One ‘descend from a great black cloud, in a bright flame of fire, and light upon the ground’ – presumably leaving an enigmatic footprint in the process, if anyone dared look. But if the mark in the sand is the devil’s work it would seem lacking in infernal cunning or even clear purpose: ‘the devil might have found out abundance of other ways to have terrified me, than this of the single print of a foot’, Robinson concludes.1 Similar arguments weigh against the footprint’s being a sign from the Almighty. It is more plausible, Robinson finally concludes, ‘that it must be some of the savages of the main land over-against me, who had wandered out to sea in their canoes’. Will they now come back in force, to ‘devour’ him?

Fear banishes ‘all my religious hope’ for a while. But gradually Crusoe’s faith in Providence returns, as does his trust in rational explanation. ‘I began to persuade myself it was all a delusion; that it was nothing else but my own foot’. He emerges from his hole and, stopping only to milk the distended teats of his goats, he returns to examine the print more carefully. In three days and nights one might expect it to have been covered over by the wind, but it is still there, clear as ever. Crusoe’s rational explanation proves to be wrong: ‘When I came to measure the mark with my own foot, i found my foot not so large by a great deal.’ Panic once more.

We are never specifically told who left the print, nor why it was just the one. But the experience changes Robinson Crusoe’s way of life. No longer supposing himself alone, he adopts a more defensive (‘prudent’) way of life. He is right to be prudent. Some two years later, on the other side of the island, he sees a boat out at sea. That far coast, he now realizes, is frequently visited – unlike his own: ‘I was presently convinc’d, that the seeing the print of a man’s foot, was not such a strange thing in the island as I imagin’d.’ Providence, he is grateful to realize, has cast him ‘upon the side of the island, where the savages never came’. Never? Who left the print then – friendly Providence, as a warning that there were savages about?

Figure 2. Illustration by George Housman Thomas, from an edition of 1865

Gradually Crusoe comes, by prudent anthropological observation, to know more about the savages – a process that culminates ten years after the footprint episode with the acquisition of his most valuable piece of property, Man Friday. The savages are, as Robinson observes, opportunist raiders of the sea – black pirates with a taste for human flesh. When they find some luckless wrecked mariner, or defenceless fellow native in his craft, the savages bring their prey to shore to cook and eat them. Then they leave. In their grisly visits they never penetrate beyond the sandy beach to the interior of the island (perhaps, as in Golding’s Lord of the Flies, there are legends of a terrible giant, dressed in animal skins, with a magical tube which spurts thunder). It is likely that the footprint must have been left by some scouting savage making a rare foray to the far side of the island. He noticed Crusoe’s boat, concluded on close inspection that it was flotsam, and went off again. Luckily the hero’s residences, livestock, and plantations were some way distant and could not be seen from this section of the shore.

But why the single footprint? Before attempting an answer one needs to make the point that although careless in accidental details (such as the trousers and the biscuits), Defoe usually handles substantial twists of plot very neatly. A good example is the corn which Crusoe first thinks is providential manna but which later proves to have a rational origin. Defoe sets this episode up by mentioning that Robinson brought back some barley seed from his wrecked ship, ‘but to my great disappointment, I found afterwards that the rats had eaten or spoiled it all’. He threw it away in disgust. Then, twenty-odd pages later, the seed sprouts. Robinson at first believes the growing barley to be a miracle. Then he puts two and two together and realizes it is the result of his thoughtlessly shaking out the bags of spoiled chicken-feed some months earlier. It is an accomplished piece of narrative.

A few pages before the episode of the footprint Defoe has Crusoe describe, in great detail, the tides which wash the island and their intricate ebbs and flows. Many readers will skip over this technical and unexciting digression. Ostensibly, Crusoe’s meditation on the ‘sets of the tides’ has to do with navigation problems. But the ulterior motive, we may assume, is to imprint in the reader’s mind the fact that the island does have tides and that they are forever lapping at its shoreline.

What we may suppose happened is the following. Crusoe has beached his boat, not on the dead-flat expanse which is what would seem likely, but on a steeply inclined beach. The unknown savage came head-on into the beach and pulled his boat on to the sand. He investigated Crusoe’s canoe, all the while walking below the high-tide line. Having satisfied himself that Crusoe’s vessel had no one in it, he returned to his own craft. Coming or going, one of his feet (as he was knocked by a wave, perhaps, or jumped away from some driftwood) strayed above the high-water mark. This lateral footprint (i.e. not pointing to, or away from, the ocean) was left after the tide had washed all the others away together with the drag marks of the savage’s boat.

Robinson Crusoe’s discovery of the footprint is, with Oliver Twist’s asking for more, one of the best-known episodes in British fiction – familiar even to those who would scarcely recognize the name of Daniel Defoe. It is also one of the English novel’s most illustrated scenes – particularly in the myriad boys’ editions of Robinson Crusoe. Most illustrations I have seen make one of three errors: they put the footprint too far from the waves; they picture Robinson as wearing shoes; they show the beach as too flat. These errors, I think, reflect widespread perplexity at the scene and a fatalistic inclination not to worry too much about its illogical details. But there are, as I have tried to argue, ways of making sense of the single footprint. And at least one illustrator has interpreted the scene as I have. Despite its rather melodramatic mise en scène, the most persuasive pictorial interpretation I have seen is this by George Cruikshank (although he too gives Robinson shoes).

Figure 3. Illustration by George Cruikshank, from an edition of 1890

Notes

1. Stith Thompson’s Motif Index of Folk Literature (Copenhagen, 1955), contains many entries on the motif of the devil – and sometimes angels – leaving single footprints in rock or soil.

* The Gutenberg text uses modernized spellings and has no chapter divisions, but a word search will readily turn up the relevant quotes.

† Giving Robinson shoes, boots, or moccasins is a very common error, although specifically contradicted by the 1719 illustration, which follows the text closely. See Fig. 1.

John Cleland Fanny Hill

Where does Fanny Hill keep her contraceptives?

I first read Fanny Hill (or, more properly, Memoirs of a Woman of Pleasure) in the 1950s, when it was still a banned book. A friend loaned me a much-thumbed copy, vilely printed in Tangiers, and evidently smuggled in by a merchant sailor. Any bookseller handling Cleland’s ‘erotic masterpiece’ in 1955 would have faced prosecution. British schoolboys caught with the book might expect instant expulsion. Adults found in possession would probably receive a formal police warning1 and summary confiscation of the offending object (which, one guesses, would be eagerly pored over at the station). Fanny Hill was a much less exciting text after it – along with Lady Chatterley’s Lover – was ‘acquitted’ and became a legal high street commodity.2 It was elevated to classic status by Penguin in 1985 and by OUP as a World’s Classic in the same year. Doubtless some of the more adventurous A-level boards will soon be prescribing Fanny Hill as a set text.

Fanny Hill was, one suspects, a subversive presence in English literature during its long career as an ‘underground’ text – particularly in the moralistic Victorian era. It seems likely that Dickens read it, and at a number of points one can plausibly detect its mark in his fiction. Mr Dick, the amiable, kite-flying idiot in David Copperfield, conceivably owes his name – and possibly more – to the idiot in Fanny Hill: ‘The boys, and servants in the neighbourhood, had given him the nickname of good-natured Dick, from the soft simpleton’s doing everything he was bid to do at the first word, and from his naturally having no turn to mischief’ (Letter the Second).

In a spirit of lascivious mischief Fanny and Louisa undress good-natured Dick. His membrum virile amazes them: ‘prepared as we were to see something extraordinary, it still, out of measure, surpassed our expectation, and astonished even me, who had not been used to trade in trifles’. Modest Fanny merely looks but the wanton Louisa must sample the aptly named Dick’s ‘maypole’. And so, we learn, do other women, inflamed by Louisa’s ‘report of his parts’. As a sexual toy, Dick has the advantage that since he remembers nothing he can be trusted to be discreet. He is no more likely to blab than a king-sized, battery-operated vibrator. Obviously Miss Trotwood would not, like Louisa, misconduct herself with her Dick – whose ‘King Charles’s head’ keeps poking in everywhere (Fanny’s true love is called Charles, we recall; he too is a great one for poking). But a spinster living alone with an adult man would surely give rise to bawdy speculation among the locals. It was Victorian folklore that all idiots had massive penises (something that features in depictions of the age’s favourite mascot, Mr Punch, and his phallic truncheon). Every schoolboy would have a sniggering awareness of the double entendre in Mr Dick’s name.

Joss Lutz Marsh, in a perceptive article,3 notes another interesting echo from Fanny Hill in Dickens’s Dombey and Son. When Florence Dombey loses her way in London she is abducted by a horrible crone who calls herself ‘Good Mrs Brown’. ‘A very ugly old woman, with red rims round her eyes’, Mrs Brown deals in rags and bones in a small way. She incarcerates Florence in a filthy back room in a shabby house in a dirty London lane. Mrs Brown then strips off all Florence’s clothes and gives her rags to cover herself with. For a few moments we picture the little girl either in her underclothes or stark naked. Suddenly Mrs Brown catches sight of Florence’s head of luxuriant hair under her bonnet and is gripped by the lust to clip the tresses off and sell them. She obviously has further plans to make money out of the child’s body which are happily forestalled when Florence escapes to be rescued by Walter.

Mrs Brown’s predatoriness should be read metaphorically, Marsh suggests. With a little adjustment we can see ‘Good Mrs Brown’ as a procuress of underage girls for immoral purposes, one of the suppliers of the ‘tribute of Babylon’. When she has stripped and shorn Florence, Mrs Brown will sell what is left to some expensive London brothel specializing in juvenile virgins. As Marsh is apparently the first to notice, there is an echo here from Cleland’s novel. When fifteen-year-old Fanny Hill comes to London the first of the procuresses she falls in with is Mrs Brown. A ‘squob-fat, red-faced’ woman of ‘at least fifty’, possessed of Messalina’s appetites, Cleland’s Mrs Brown is not an attractive personage, if not quite as revolting as her Dickensian namesake. Cleland’s bawd tries to sell Fanny’s maidenhead to the odious Mr Crofts but when that fails (Fanny having heroically kept her legs crossed) Mrs Brown treats the young virgin not at all badly. She is put in the charge of a kind-hearted trull, ‘Mrs’ Phoebe Ayres, ‘whose business it was to prepare and break such young fillies as I was to the mounting-block’ (Letter the First). Phoebe is Fanny’s ‘tutoress’. By cunning (and gentle) lesbian caresses the older woman stimulates Fanny’s latent sensuality and by voyeuristic spectacles she instructs the child in the mechanics of sex and its repertoire of ‘pleasures’. Phoebe also inducts her pupil into ‘all the mysteries of Venus’. They probably include, as we deduce from Fanny’s later career, planned parenthood.

Having benefited from Phoebe’s tuition, Fanny is now ready for the next phase of her career. She elopes with her nineteen-year-old ‘Adonis’, Charles, to a convenient public house in Chelsea, where she finally surrenders her maidenhead. The young lovers enjoy each other many times and with excesses of mutual ‘pleasure’. Physically Charles is both a man of wax and a man of means. The only son of a prosperous revenue officer, he is also the favourite of a wealthy grandmother. Charles rescues Fanny from Mrs Brown’s clutches and promptly sets her up as his mistress in apartments with another bawd – Mrs Jones. Fanny, looking back on events, expresses a strong dislike for this new protector. Mrs Jones is a ‘private procuress … about forty six years old, tall, meagre, red-haired, with one of those trivial ordinary faces you meet with every where … a harpy’ (Letter the First). On the side she engages ‘in private pawn-broking and other profitable secrets’ (abortion, as we apprehend).

Fanny resides under Mrs Jones’s uncongenial roof for eleven months, at which point she is, as she tells us, ‘about three months gone with child’. One deduces that she is pregnant by policy not accident. Over the months Charles has been ‘educating’ her – expunging her rusticity, making her a lady ‘worthier of his heart’. His love, she protests, is of ‘unshaken constancy’, and he ‘sacrificed to me women of greater importance than I dare hint’ (Letter the First). It is clear that Fanny fondly expects to marry Charles – despite the class difference and the fact that he found her in a London brothel. It is to this end that she has allowed herself to become pregnant – to force his hand.

What follows in Fanny’s account is highly suspect. She herself confesses that she will ‘gallop post-over the particulars’. According to her skimped version of events, Charles (who has just learned that Fanny is with child) is kidnapped by his father and put on a boat leaving that hour for the South Seas where a rich uncle has just died. He is not allowed to dispatch any messages (or money) back to shore. Although it is said that he later sends letters, they all ‘miscarry’. Implausible, one might think.

Fanny learns from a maid that Charles has left the country and that any attempt to communicate with him is hopeless. She is alone again in the world, penniless and pregnant. Her ruse, if ruse the pregnancy was, has backfired. What actually happened seems clear enough, if we discount (as probability suggests we should) Fanny’s version of events. Charles confessed to his father that he had made a woman of the town pregnant. Her bawd would swear the child was his. It would be very embarrassing for the revenue officer – and expensive. Aged twenty, Charles could not marry without paternal consent even if he wanted to, and he probably does not intend to ruin his prospects by setting up house with a reformed whore. He is sent abroad for a couple of years until the whole thing blows over. The traditional solution for young men of good families who got into this kind of pickle was to send them away – preferably as far and for as long as possible.

According to Fanny she swoons when she hears the news of her lover’s disappearance and, after ‘several successive fits, all the while wild and senseless, I miscarried of the dear pledge of my Charles’s love’ (Letter the First). What seems more likely is that Mrs Jones aborted the child. Fanny now has only one resource – to sell herself, preferably as a ‘virgin’ newly up from the country. She owes Jones a huge sum for rent (over £23), and unless she can go on the game she will find herself in prison – as her landlady unkindly reminds her. Carrying Charles’s ‘pledge’ to term is out of the question unless she wants to enter motherhood in Bridewell.

Under Mrs Jones’s guidance, Fanny for the first time takes paying clients. Some welcome stability enters her professional life when she becomes the mistress of Mr H—. But, after seven months, in sheer boredom, she surrenders to her protector’s massively endowed footman, Will. When she is discovered in flagrante, Mr H— turns her into the streets with 50 guineas (he is not a hardhearted man, we apprehend). Thus Fanny, still only sixteen, comes under the care of the third and most amiable of her bawds, Mrs Cole. Mrs Cole is not only good-natured, but conscientiously instructs her whores in ‘prudential economy’. She is a skilled madame. ‘Nobody’, Fanny says, had ‘more experience of the wicked part of the town than she had [or] was fitter to advise and guard one against the worst dangers of our profession’ (Letter the First). One main danger is disease; the other, we guess, is pregnancy.

Enriched by three years’ service with Mrs Cole, Fanny (‘not yet 19’) finds herself possessed of a fortune and, thanks to her patroness, knows how to look after her nest-egg. She is now an independent woman and has been making desultory enquiries about the whereabouts of the errant Charles. On a triumphant trip to show herself off in her native Lancashire village she is finally reunited with her lover by accident. He has been shipwrecked coming back from the South Seas. More to the point, he is now a poor man. The tables are turned but Fanny’s heart is true. She accepts him as her husband and they go on to have ‘those fine children you have seen by this happiest of matches’.

Over the five years of our acquaintance with her, Fanny avoids pregnancy when it would be professionally inconvenient. She becomes pregnant when (as she wrongly thinks) it will coerce Charles into marriage. She has legitimate children after marriage. How does she control her reproductive functions so efficiently? Fanny Hill is unusual among works of popular pornography in that it does not assume that the sexual act has no consequences – venereal disease and pregnancy are always darkening the edge of the heroine’s ‘pleasures’. The house of accommodation under the supervision of a knowledgeable bawd offers invaluable prophylaxes for someone in Fanny’s position. It is clear that Mrs Cole screens clients to eliminate the grosser disease carriers.4 It is only slightly less clear that the Cole establishment is furnished with an efficient contraceptive apparatus for the working girls. The nature of the apparatus is obliquely described in the scene where Fanny has to fabricate a broken hymen for the benefit of Mr Norbert.

In each of the head bed-posts, just above where the bedsteads are inserted into them, there was a small drawer, so artfully adapted to the mouldings of the timber-work, that it might have escaped even the most curious search: which drawers were easily opened or shut by the touch of a spring, and were fitted each with a shallow glass tumbler, full of a prepared fluid blood, in which lay soaked, for ready use, a sponge, that required no more than gently reaching the hand to it, taking it out and properly squeezing between the thighs. (Letter the Second)

The defloration of a virgin would be a relatively rare event in Mrs Cole’s house. Rich fools like Mr Norbert are not come by every day. But the sponge and the tumbler would have a more quotidian usage, justifying the expensive alterations to the bedroom furniture. As Peter Fryer records in his history of birth control, there were in the eighteenth century five approved forms of contraception: coitus interruptus, anal intercourse, primitive condoms, exotic prophylactic potions (spermicides or abortifacients), and vaginal sponges – usually dipped first in a tumbler of some such spermicide as brandy or vinegar.5 There is no coitus interruptus in Fanny Hill – the ‘balsamic fluid’ is invariably ‘inspers’d’ in the woman’s ‘seat of love’. Fanny, her fellow whores, and her bawds have a holy horror of sodomy. There is no mention of condoms – which in this period are associated less with the class of whoremongers who patronize Fanny than with virtuoso libertines like Casanova (whose ‘English overcoat’ was made of sheep’s gut). Vaginal sponges, however, would seem to be quite at home in the world of Fanny Hill, conveniently available on every bedpost.

Notes

1. When, in the 1940s, it was learned that the Cambridge teacher and critic F.R. Leavis was in the habit of referring to James Joyce’s Ulysses in his classes, he was visited and warned by the police.

2.Fanny Hill was prosecuted and banned by London magistrates in the early 1960s. The ban was never formally lifted, although later in the decade Cleland’s novel drifted back into print. See J.A. Sutherland, Offensive Literature (London, 1982), Chapter 3.

3. Joss Lutz Marsh, ‘Good Mrs Brown’s Connections: Sexuality and Story-telling in Dealings with the Firm of Dombey and Son’, English Literary History, 58: 2 (Summer 1991), 405–26.

4. See the episode with the sailor in which Mrs Cole specifically warns Fanny against the dangers of disease (‘the risk to my health in being so open-legg’d and free of my flesh’).

5. Peter Fryer, The Birth Controllers (London, 1965), chs. 1–2.

Henry Fielding Tom Jones

Who is Tom Jones’s father?

According to the scholar John Mullan, even readers who know Fielding’s novel well will struggle with the above question, without recourse to the book. One can see why Tom’s paternity should be something of a poser. The crucial information is held back until the very last pages and then passed over quickly. Maternity is something else. That young Jones is Bridget Allworthy’s offspring will be picked up early by astute readers. It is implicit in Miss Allworthy’s instant partiality for the foundling – a partiality which continues even after she has a legitimate child of her own (whom she evidently hates as his father’s son) – and her refusal to join in the persecution of Jenny Jones. Fielding sows a number of such hints in the early chapters. But the author tantalizingly withholds the identity of Tom’s father – even from the characters themselves at crucial junctures. It was, as Jenny tells Mr Allworthy, always Bridget’s intention ‘to communicate it to you’. But when she sends her deathbed confession via Dowling, it is frustrating (particularly for Blifil, who intercepts the message) that Bridget does not, even on the brink of eternity, name Tom’s father. ‘She took me by the hand,’ Dowling recalls, ‘and, as she delivered me the letter, said, “I scarce know what I have written. Tell my brother, Mr Jones is his nephew – He is my son. – Bless him,” says she, and then fell backward, as if dying away. I presently called in the people, and she never spoke more to me, and died within a few minutes afterwards’ (Book 18, Chapter 8). Her son, and who else’s?