Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Polygon

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

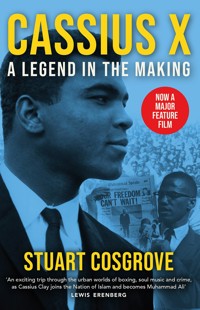

Now a Major Feature Length Documentary: 'Cassius X: Becoming Ali' (Cinema release Spring 2023) Miami, 1963. A young boy from Louisville, Kentucky, is on the path to becoming the greatest sportsman of all time. Cassius Clay is training in the 5th Street Gym for his heavyweight title clash against the formidable Sonny Liston. He is beginning to embrace the ideas and attitudes of Black Power, and firebrand preacher Malcolm X will soon become his spiritual adviser. Thus Cassius Clay will become 'Cassius X' as he awaits his induction into the Nation of Islam. Cassius also befriends the legendary soul singer Sam Cooke, falls in love with soul singer Dee Dee Sharp and becomes a remarkable witness to the first days of soul music. As with his award-winning soul trilogy, Stuart Cosgrove's intensive research and sweeping storytelling shines a new light on how black music lit up the sixties against a backdrop of social and political turmoil – and how Cassius Clay made his remarkable transformation into Muhammad Ali.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 473

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

PRAISE FOR CASSIUS X

‘A delightful ride in a cherry-red Cadillac, with soul music on the radio and a steady hand at the wheel. A thoroughly enjoyable journey’ Jonathan Eig, author of Ali: A Life

‘Crisply written, fast-paced and original, this book surges with the kind of effervescence we have long associated with a young Cassius Clay. Even the most informed Muhammad Ali fan will learn something new from this book, . . . Filled with colourful details, with a learned eye toward the music of the era, Cassius X hits all the right notes’ Michael Ezra, author of Muhammad Ali: The Making of an Icon

‘An exciting trip through the urban worlds of boxing, soul music, and crime, as Cassius Clay joins the Nation of Islam, becomes Muhammad Ali, and ascends the ranks of boxing to become World Heavyweight Champion during the early 1960s’ Lewis Erenberg, author of The Rumble in the Jungle

‘There are many books about Muhammad Ali, but none like Stuart Cosgrove’s Cassius X. Focusing on the athlete’s transformation from Cassius Clay to Muhammad Ali, Cosgrove provides the reader with an extraordinary view of the radical psychological and spiritual changes that Ali experienced during the early part of his career. He does this while expertly weaving in the social upheaval during the Civil Rights era and how those events shaped the boxer’s personal evolution. The book is a deeply personal look at one of ‘The Greatest’ public figures of the last one hundred years and is a model of how biographies of African-Americans should be written’ Ray Winbush, author of Belinda’s Petition: A Concise History of Reparations for the Transatlantic Slave Trade

PRAISE FOR STUART COSGROVE’S SIXTIES SOUL TRILOGY

HARLEM 69: THE FUTURE OF SOUL

‘Cosgrove’s impressive, dogged groundwork is matched by a deep devotion to the music that is the backbone of the narrative . . . An essential read for anyone interested in the politics and culture of the late 60s, when soul music reflected the momentum of a tumultuous era that resonates still.’

Sean O’Hagan, The Observer

‘An impressively granular month-by-month deep dive into Harlem’s fertile musical response to a time of social and political upheaval.’

Financial Times, Best Books of 2018

‘Not only a gripping socio-cultural history, it feels truly novelistic. Harlem throbs thrillingly . . . and Cosgrove captures it vividly: heroin, civic decay, gravediggers’ strikes, gender-fluid gangsters, Vietnam vets, Puerto Rican boxers and all . . . Harlem 69 makes startling connections across time and place.’

Graeme Thomson, Uncut

‘The best music writing this year is about black music. Cosgrove’s deep dive into the year’s events is an epic feat of archival research that has been expertly marshalled into a narrative that joins the dots between Donny Hathaway, Jimi Hendrix, the Black Panthers, police corruption and the Vietnam war.’

Teddy Jamieson, The Herald, Best Music Books of 2018

‘Cosgrove’s series can be read separately, but to read them as a trilogy gives a real sense of black music and social movements . . . paints a vivid, detailed picture of the intensity of social deprivation and resistance, and also the way that’s reflected in, but also affected by, the music of those cities. Reading Harlem 69 made me want to do two things – dig out and play some of the records mentioned, and fight the powers that be.’

Socialist Review

MEMPHIS 68: THE TRAGEDY OF SOUTHERN SOUL

Winner of the Penderyn Music Book Prize, 2018

Mojo – Books of the Year #4, 2017

Shindig – Book of the Year, 2017

‘Offers us a map of Memphis in that most revolutionary of years, 1968. Music writing as both crime reporting and political commentary.’

The Herald

‘Cosgrove’s selection of his subjects is unerring, and clearly rooted in personal passion . . . an authorial voice which is as easily, blissfully evocative as a classic soul seven-inch.’

David Pollock, The List

‘Highly recommended! Astounding body of learning. Future classic. Go!’

SoulSource.co.uk

‘As ever, Cosgrove’s lucid, entertaining prose is laden with detail, but never at the expense of the wider narrative . . . A heartbreaking but essential read, and one that feels remarkably timely.’

Clash Magazine, Best Books of 2017

‘Stuart Cosgrove’s whole life has been shaped by soul – first as a music journalist and now as a chronicler of black American music’s social context.’

Sunday Herald

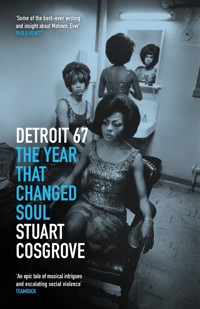

DETROIT 67: THE YEAR THAT CHANGED SOUL

‘The subhead for Stuart Cosgrove’s Detroit 67 is “the year that changed soul”. But this thing contains multitudes, and digs in deep, well beyond just the city’s music industry in that fateful year . . . All of this is written about with precision, empathy, and a great, deep love for the city of Detroit.’

Detroit Metro Times

‘Big daddy of soul books . . . weaves a thoroughly researched, epic tale of musical intrigues and escalating social violence.’

TeamRock

‘Cosgrove weaves a compelling web of circumstance that maps a city struggling with the loss of its youth to the Vietnam War, the hard edge of the civil-rights movement and ferocious inner-city rioting . . . a whole-hearted evocation of people and places filled with the confidence that it is telling a tale set at a fulcrum of American social and cultural history.’

The Independent

‘The story is unbelievably rich. Motown, the radical hippie underground, a trigger-happy police force, Vietnam, a disaffected young black community, inclement weather, The Supremes, the army, strikes, fiscal austerity, murders – all these elements coalesced, as Cosgrove noted, to create a remarkable year. In fact, as the book gathers pace, one can’t help think how the hell did this city survive it all? . . . it contains some of the best ever writing and insight about Motown. Ever.’

Paolo Hewitt, Caught by the River

‘Leading black music label Motown is at the heart of the story, and 1967 is one of Motown’s more turbulent years, but it’s set against the backdrop of growing opposition to the war in Vietnam, police brutality, a disaffected black population, rioting, strikes in the Big Three car plants and what seemed like the imminent breakdown of society . . . You finish the book with a real sense of a city in crisis and of how some artists reflected events.’

Socialist Review

© James Drake / Sports Illustrated Classic

Cassius Clay counts down the last few days of 1962. Unknown to the world, he has quietly joined the ranks of the Nation of Islam and is already wearing the sober dark suit and tie that reflects his choice. It will be another fifteen months before he will be universally known as Muhammad Ali.

First published in Great Britain in 2020 by Polygon, an imprint of Birlinn Ltd.

Birlinn Ltd

West Newington House

10 Newington Road

Edinburgh

EH9 1QS

www.polygonbooks.co.uk

1

Copyright © Stuart Cosgrove 2020

The right of Stuart Cosgrove to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved.

Every effort has been made to trace copyright holders.

If any omissions have been made, the publisher will be happy to rectify these in future editions.

ISBN 978 1 84697 579 0

eBook ISBN 978 1 78885 297 5

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available on request from the British Library.

Typeset by 3btype.com

I am America. I am the part you won’t recognize. But get used to me. Black, confident, cocky; my name, not yours; my religion, not yours; my goals, my own; get used to me.—Cassius X, 1964

The common goal of 22 million Afro-Americans is respect as human beings, the God-given right to be a human being. Our common goal is to obtain the human rights that America has been denying us. We can never get civil rights in America until our human rights are first restored. We will never be recognized as citizens there until we are first recognized as humans.—Malcolm X, 1964

CONTENTS

Foreword

Miami: Where Neon Goes to Die

Detroit: Detroit Red and the Sound of Young America

Philadelphia: The Guy with the Goods

New York: The Winter of Boxing

London: Scandal in Soho

Miami: The Fight That Changed America

Requiem

Boxing and Soul: A Playlist

Bibliography

Index

FOREWORD

Cassius X is the story of an extraordinary human being, but more importantly it is the story of the many social forces that shaped Muhammad Ali.

The book is largely set in 1963 in the run-up to Cassius’s first title fight with Sonny Liston in Miami, and focuses on the months when he was using the name Cassius X. He was yet to complete his conversion to Islam, at which point he was given the name Muhammad Ali.

At one level it can be read as a prequel to my soul trilogy – Detroit 67: The Year That Changed Soul, Memphis 68: The Tragedy of Southern Soul and Harlem 69: The Future of Soul – in that it details the emergence of soul music as one of the dominant popular musical genres of the sixties, but, at heart, it is about the complex political and religious backdrop that created Cassius X and, in turn, Muhammad Ali, and the remarkable sorcery he brought to boxing and the world of entertainment.

Many good biographies have been written about Muhammad Ali that span his entire life: that is not what this book is about. Cassius X portrays a man in compression, in the days when the young fighter was exploring his identity, moulding his image and forging advantageous friendships with Malcolm X, Sam Cooke and the media. It is about his role as a witness, not simply to the divisive racial landscape of America, but to the new, self-confident forms of music and entertainment that enlivened his youth.

I owe a huge debt of gratitude to my publisher Polygon, particularly my editor Alison Rae, and to my American publisher Chicago Review Press.

My personal thanks to my friends and family and, as ever, to the weird academy of northern soul.

Stuart Cosgrove Glasgow 2020

© Flip Schulke Archives / Corbis Premium Historical

Cassius takes a break from training in Chris Dundee’s gym on 5th Street in Miami. He is wearing a T-shirt designed by his father, who was a signwriter back in their native Louisville, Kentucky. Photographer Flip Schulke took hundreds of photographs of the boxer between 1961 and 1964, including the iconic swimming-pool shots. Cassius had boasted that he trained underwater to strengthen his jabbing, but it was a fabrication concocted by Cassius and his trainer. He didn’t know how to swim.

MIAMI

Where Neon Goes to Die

In the first bleary-eyed days of 1963 Miami woke up to a raging hangover. The city was crammed with well-wishers, con artists and the walking dead. Snowbirds, in their colourful Hawaiian shirts, had flocked to the Florida beaches from Chicago and Detroit, to escape the deafening sounds of the big industrial cities and the unforgiving northern weather. Hotels bulged at the seams and disappointed guests could be seen dragging their bags along Collins Avenue in the vain hope of a late vacancy. Inside the permafrost lobbies, where high rollers escaped the heat, men in unseemly shorts swaggered around the shimmering casinos, leaving crumpled cash tips and suspicion in their wake.

Cassius Clay had been in Miami for over two years now and he had never witnessed such levels of edgy nervousness. The city was restless and rotting to its core. According to the beat comedian Lenny Bruce, who damned urban America with faint praise, Miami was the place where ‘neon went to die’. Across whole swathes of the city neon flickered on and off, signage unsteadily jumped to life, and broken glass littered the sidewalks. The garish signs that looked so alluring on postcards were wheezing their last breath and advertising nothing more than a city facing decline. Decay had infected palms in the most shaded parts of the city, and bud rot, the lethal fungal disease, had attacked the once majestic trees, staining their drooping hands an ugly shade of nicotine yellow.

Miami had enjoyed an unrestrained growth after the war, driven by cheap air flights and the rise of air conditioning, but the boom was unsustainable. Work was short-term and unpredictable, unemployment surged and ebbed with the seasons, and the influx of immigrants from Cuba and the Caribbean put unmanageable pressure on social services. Many mid-priced hotels had struggled to keep up with refurbishment plans and repairs to hurricane damage, so swathes of the city looked grubby, dysfunctional and unloved.

Despite all of that, the myth of Miami thrived, and the city’s sunshine reputation somehow shook off harsher realities. In her insightful book Miami, the celebrated author Joan Didion claimed that ‘Miami seemed not like a city at all but a tale, a romance of the tropics, a kind of waking dream in which any possibility could and would be accommodated’. But wrapped up in the dream Didion also saw a city situated at the geographic end of a pistol, an American city ‘populated by people who also believed that the United States would betray them’. And the man the Cuban denizens of Miami believed had betrayed them most deeply was the president himself.

John F. Kennedy was in town and his presence had added increased tension to the tumultuous self-indulgence of New Year. The year 1963 was destined to become one of dark conspiracy, the year the president was assassinated. But something else was stirring, hidden away on the other side of this segregated city.

Soul music was rippling beneath the surface, barely audible at first, but about to break across America like an electric thunderstorm and dominate the eventful years yet to come.

It was in Miami that Cassius Marcellus Clay, a lanky youth from Louisville, Kentucky, had fashioned an outrageous dream – to become the heavyweight champion of the world. Cassius and his advisers in Louisville had identified the veteran trainer Angelo Dundee as the man most likely to advance the young boxer’s career. Dundee had left his native Philadelphia and was based at his brother Chris Dundee’s Gym on Miami’s 5th Street. So an eighteen-year-old Cassius had arrived by train from Kentucky in November 1960 to join the claustrophobic boxing academy in ‘a steamy, scruffy loft above a liquor store’, as the Miami Herald described it, on a crumbling corner downtown.

Reticent and unsure where he was going, Cassius was met at the station by his new trainer and an effusive group of Cuban boxers who drove him to an unfamiliar and heavily curtained home. The residents spoke only Spanish and the young boxer retreated deep into himself, unsure of how to communicate. As night descended, he was shown to a cluttered room near the Calle Ocho strip in the Little Havana neighbourhood, where he dumped his training bags and faced an ignominious baptism. He shared his first uncomfortable night in Miami sleeping nose-to-foot with Luis Rodríguez, the brilliant Cuban boxer who once boasted that he had the longest nose in America (his fans in Cuba called him ‘El feo’) and could fire snot that would kill Fidel Castro. In a darkened room infested with mosquitoes and the piercing smell of sweat, Cassius lay awake listening to distant Hispanic voices and Rodríguez’s thunderous snores.

An avowed enemy of Castro’s regime, Rodríguez was a lynchpin in Miami’s many hives of conspiracy and a close friend of Ricardo ‘Monkey’ Morales, the former Cuban intelligence officer who had defected to the USA in 1960, where he was contracted by the CIA as a paramilitary officer to fight secret wars and connive with his exiled compatriots, including the boxers who trained with Cassius in the 5th Street Gym. Rodríguez played the role of patriot; a propagandist to the core, he often tried to interest a distracted and disinterested Cassius in the latest gossip sweeping through the exiled Cuban community. Rodríguez had taken on the role of the gymnasium elder, showing visitors around, issuing locker keys and trading jokes with the swarm of boxers who huddled around the ring and concealed ammunition in the ramshackle lockers. It was here amid the sawdust and the whispering Cuban middleweights that Cassius perfected his trademark shuffling dance style and the rhyming ebullience that made him famous.

Rodríguez and the restless kid from Louisville formed a close and unlikely bond, and throughout their odd friendship, they shared a belief that boxing was first and foremost part of the entertainment industry, dangerous and deadly, but entertainment nonetheless. Unsuccessfully coaching him about the warring enigmas of Cuban politics, Rodríguez recounted the names of remarkable generation of expatriates, the great Cuban boxers who had escaped Cuba and were shaping a new story for boxing. Cassius would come to know them, and share training facilities with them in the weeks and months to come. Each of their names sounded so sweet, so satisfying – Kid Chocolate, Kid Gavilán and the elegant featherweight Ultiminio ‘Sugar’ Ramos. Rodríguez convinced Cassius that if he spent a day watching the quixotic Cubans move on the canvas, he too could learn to dance like the wind. Cassius listened and smiled. He warmed to Luis Rodríguez and saw a flicker of his own personality reflected in the Ugly One’s gregarious antics. ‘Rodríguez is a clown, a friendly clown,’ Robert H. Boyle wrote in Sports Illustrated, as if the era of the quixotic clown was about to revolutionise the world of boxing.

Spooked by his first sleepless night in Miami, Cassius vowed to find his own people, and within less than thirty-six hours he had convinced Angelo Dundee to stretch the 5th Street Gym budget and fund a cheap hotel room away from the Beach in the teeming Overtown ghetto. He initially stayed at the Mary Elizabeth Hotel on North West Second Avenue – described by his gym doctor Ferdie Pacheco as ‘a den of thieves, pimps and prostitutes’ – and after another week of uncomfortable nights he moved to the Sir John Hotel, the coolest R&B venue in Overtown. The Sir John was a landmark, the epicentre of Miami’s fledgling soul scene and a much more comfortable hotel, with its own swimming pool and a late-night soul club, the Knight Beat. It was to become Cassius’s on-and-off home throughout much of the next three years, and the place where his life took on a new direction. It was here in an otherwise modest hotel room that he began to transform his image, his religious beliefs and, eventually, his name.

On his first night in the hotel, he had unpacked his gym bag, the meagre contents giving a clue to his personality. Bundled in amongst the familiar boxing paraphernalia (gum shields, bonding tape and a tin of Vaseline) was the primitive kit of an amateur conjurer – a magic wand, a pack of dice, playing cards and battered top hat. A trick spider clung to the inside of the bag to be used as a practical joke in the stormy days and stifling months to come. He unfolded his 1960 Olympic vest and hung it over a chair, a showy reminder of his success so far. It was in Rome that Cassius had racked up his first significant victory, when he won the light heavy-weight gold medal by defeating the Pole, Zbigniew Pietrzykowski.

Floyd Patterson, heavyweight champion of the world in the early sixties, told Esquire magazine that when he first met Cassius Clay, ‘his public image was so different. It was in 1960. I was the champion then and was travelling through Rome. I’d had an audience with the Pope, then visited the American Olympic team there and met Cassius Clay. He was the star boxer for the American team, and he was very polite and full of enthusiasm, and I remember how, when I arrived at the Olympic camp, he jumped up and grabbed my hand and said, “C’mon, let me show you around.” He led me all around the place and the only unusual thing about him was this overenthusiasm, but other than that he was a modest and very likable guy.’ Cassius came to realise that modesty was a weak currency and that the dollars seem to favour those who demanded attention. He became known as a boy with a near desperate desire to entertain and an adolescent whose demeanour often veered towards an irritating swagger. When he first arrived in Miami, he was largely unknown out on the streets, but his instincts served him well and his showy personality, however much it was contrived, would come to shine.

In the Orange Bowl Stadium, west of downtown, 75,000 spectators crammed in to watch a spectacular opening ceremony and witness President Kennedy and the First Lady, Jacqueline Bouvier Kennedy, being unveiled as the guests of honour at the city’s most famous sporting event – the annual Orange Bowl. The president descended from the skies by helicopter before emerging onto the field surrounded by a Praetorian guard of Secret Service agents, their wired professionalism hidden behind sunglasses in the glaring Florida sun. Clint Hill, unknown and unrecognisable, stuck to the Kennedys like glue, his edgy stillness and dark glasses giving out the silent brooding menace of an undercover operative. Hill had spent the late fifties as a Special Agent in the Denver field office before being assigned to the elite White House Detail. Later in the year, he would form part of the motorcade in Dallas and was seen running from the limousine behind the president to shield Jackie Kennedy as the assassin’s bullets rained down on them.

By the first days of 1963, a tangible paranoia had tightened around the president. The Secret Service had scoured the Americana Hotel in Bal Harbour for a full week before his arrival, securing a block of rooms on a lower floor instead of the harder-to-protect penthouse suite. Hotel workers were instructed to take sledge-hammers to a wall to create a secure doorway to allow President Kennedy to enter and leave under protection. Out in the exposed bleachers of a high-profile football game, nerves were shredded as the momentum of the crowds separated Kennedy from his security. His celebrity was irresistible. Surrounded by congressmen, political leeches and delighted tourists, the president tossed a coin from the stands prior to the start of the game. Historian Paul George describes him looking ‘cool in what appeared to be Ray-Ban sunglasses while puffing on a cigar’.

The Kennedys were at the height of their fame and had brought political allure to a city already reeking of cheap glamour. As the opening parade passed, Miss Florida was carried on a float of giant alabaster oranges, and marching bands dressed as characters from ancient Rome paid tribute to the movie Ben Hur. Hundreds of locals from Miami’s expatriate Cuban community crowded into the stadium. Teresita Rodríguez Amandi, who was ten at the time and had fled from Cuba to Miami with her parents the year before, told the Miami Herald, ‘I remember seeing him from the bleachers I was sitting in with my family. It was a very important day for us. It was the first time I would see the President before my very eyes.’ In front of him in the stadium were the two competing teams – Alabama and Oklahoma – and the massed ranks of their college marching bands. The game would become known to football aficionados as the ‘Bama Show’, in which Alabama linebacker Lee Roy Jordan almost single-handedly destroyed Oklahoma.

In an act of presidential manipulation, pride of place in the stadium had been reserved for an unorthodox group of VIPs, the ragged paramilitary army of Brigade 2506, the CIA-sponsored group of Cuban exiles who in 1961 had invaded their homeland and spectacularly failed to overthrow Fidel Castro’s revolutionary government. The invasion had ended in bloody defeat with 114 dead and 1,189 Cuban exiles captured. Reflecting on their humiliation, the surviving members of Brigade 2506 were either sceptical of or, in some cases, the sworn enemies of President Kennedy. Whatever he tried to do to accommodate them was never enough. The Cuban counter-revolutionaries held the president in part responsible for their demeaning retreat and blamed him for failing to provide air cover at a critical moment in their assault. One by one, the Cubans grudgingly shook hands with Kennedy, unsure whether their presence would look like courage or capitulation.

Kennedy’s main reason for travelling to Miami was neither the sun nor the sport. He hoped to reframe the catastrophic Bay of Pigs invasion and turn it into a heroic military adventure. It was set up so that he could honour the fighters on live television. A packed arena watched him accept delivery of a canary-yellow battle flag, handed to him by two local veterans, Erneido Oliva, the deputy commander of Brigade 2506, and Manuel Artime, a one-time member of Castro’s revolutionary army, who had been recruited by American counterintelligence to lead the attack on the island. At a podium near the field of play, surrounded by red gerbera daisies and supported by his wife Jackie, who was dressed in a powder-pink summer suit, Kennedy told the crowd and the bristling brigade leaders, ‘This flag will be returned to this brigade in a free Havana.’ It was powerful theatre, which tried gamely to rescue a propaganda victory from what was a horrendous defeat, but they were words that would be deliberately misinterpreted in Miami, seen as a coded clue that another invasion was imminent. This was not the case, and so the open sore festered into a more malicious resentment. Kennedy’s charm worked almost every-where but not among the Miami Cubans where he was seen as a two-faced, conniving little shit.

The Bay of Pigs was to remain an open wound in American politics for many years to come, with Cuban exiles frequently implicated in the flood of conspiracy theories that surrounded Kennedy’s assassination. President Lyndon Johnson, who took up office as a consequence of Kennedy’s murder, once claimed that, together with the CIA, Kennedy had run a ‘damned Homicide Inc. within the Caribbean’. Unbelievably, a generation later, a cadre of Cuban exiles, survivors of the Bay of Pigs disaster, was among the burglars who broke into the Democratic National Committee Headquarters at Watergate. Their resentments were slow to subside, if they ever did. Subsequent histories of the invasion have tried to pluck honour from the humiliation – historian Theodore Draper called the invasion ‘the perfect failure’ and author Jim Rasenberger called it ‘the brilliant disaster’ – but there was nothing either perfect or brilliant about the Bay of Pigs, and its fallout had a devastating impact on Miami, turning it into a cloistered hive of intrigue, conspiracy and criminal plotting. Armed with guns, bombs and battered pride, the Cuban ex-patriots believed that history had sold them short. As the full extent of the failure of the Bay of Pigs invasion struck home, a deal was struck with Cuba.

Less than two weeks before Kennedy’s arrival in Miami, the US Government had donated $62 million worth of food and medicine to the impoverished island as a form of ransom for more than 1,100 Brigade fighters captured in the invasion. What the president could not disguise was that Cuba had stood up to America. A humanitarian crisis had been forced on the embattled island and floods of refugees left to seek citizenship in the USA, changing the urban character of Miami for ever. Large-scale migration into Miami exploded after 1959. Most Cubans arrived in the city via special humanitarian provisions or political asylum, citing Communist oppression at home. The feeling was mutual. Cuba waved goodbye to families it described as ‘undesirables’ and took the opportunity to empty the jails of criminals of every description. Some chose to leave, others were encouraged, and caught up in the diaspora were genuinely needy families who took the calculated risk that life in America would be better for them and their children.

© Everett Collection Historical / Alamy Stock Photo

A group of volunteers receive a physical at one of the CIA’s recruiting offices in Miami. Cuban refugees volunteered to fight against Fidel Castro in what became known as the Bay of Pigs invasion of April 1961. The 5th Street Gym where Cassius trained was home to one of the greatest generations of émigré Cuban boxers and a hotbed of anti-Castro sentiment.

Cassius’s training partner, Luis Rodríguez, had been the Cuban welterweight champion back in January 1959, when the Batista Government was overthrown by Castro’s revolution. Then, when professional sport fell out of favour with the new Communist regime, he emigrated to Miami to become one of the mainstays of the 5th Street Gym. Waves of Cuban immigration had been given the gloss of free-world propaganda, the weekly charter flights from Varadero to Miami flew twice a day, and a converted army barracks on the perimeter of Miami International Airport was branded ‘Freedom House’ and provided makeshift bunk-bed accommodation for arriving families. The Cuban population in the United States grew almost sixfold within a decade, from 79,000 in 1960 to 439,000 in 1970. Miami became the capital city of Cuba in exile, and in time Cubans constituted 56 per cent of the population. In the words of a reporter for the Miami Herald, they became a ‘teeming, incomprehensible presence’.

In the meantime, the tourists who clung to the beaches and the lobbies of their grand hotels were largely ignorant of the incomprehensible Cubans and the underground sounds rallying in the bars and nightclubs of the Overtown ghetto. This was the other Miami, a mess of pastel-coloured concrete homes, jerry-built rooftops, pool halls and illegal bars, hidden away beneath the towering canopies of the I-95 highway. Firecrackers burst in the skies, fried oysters blackened on the grills, and sickly cocktails were cut with raw alcohol. Vials of intense Colombian cocaine were sold furtively on corners and the debris from Hurricane Donna still littered the side streets. Cassius found himself surrounded by squalor, fast living and temptation, but he vowed to resist it in the pursuit of discipline and success in the ring.

Each afternoon after his intensive training sessions Cassius and his brother Rudy, who had come to join him in Miami after high school, would walk over to The Stroll, the stretch of 2nd Avenue in Overtown, an African-American area populated with barbershops, record stores and all-day bars. Cassius ran a tab up at the Famous Chef restaurant next door to the hotel and hung out at Sonny Armbrister’s barber shop, where he quickly established a reputation for speaking the dozens, the rhyming rap game that was the mouthy pursuit of young African-Americans. It was here that Cassius witnessed the first days of soul music close up and met three men who to various degrees would all play a role in the development of his life. Coincidentally, they were all called Sam. Sam Saxon would recruit him into the Nation of Islam, the controversial religious group that would shape his ideas and attitudes to life; Sam Moore, a Miami soul singer and ex-convict, was an MC at the Knight Beat and within a few years would be half of Stax-Atlantic’s famous male duo Sam and Dave; and Sam Cooke, the legendary gospel-pop star, would arrive in Miami to record one of the most controversial live albums in the history of black music and later use his formidable contacts book to secure a recording deal for Cassius with New York’s Columbia Records. Cooke was one of a group of friends from the world of soul music whom Cassius carefully cultivated. Among the others were the twist-craze showman Chubby Checker; his label mate Dee Dee Sharp; Motown’s blind prodigy Little Stevie Wonder; the R&B star Lloyd Price; the East Orange, New Jersey, singer Dionne Warwick; Veronica Bennett, lead singer of The Ronettes (later to become known as Ronnie Spector); and Ben E. King, the Harlem soul crooner whose famous hit ‘Stand By Me’ Cassius covered on his debut album.

Cassius’s friendship with Sam Cooke burned bright at a time when black music was at a crossroads: gospel was spilling from churches across the nation into the bedrooms of the young, transforming love for the Lord into a more sexual and secular kind of romance. The record producer Jerry Wexler once described the former gospel star Sam Cooke as the personification of soul music’s journey: ‘It was all there, the exquisite exact intonations, the sovereign control of tone and timbre, the control of the subtlest pitch shadings, bends and slurs.’ Sam Cooke’s was the voice that gave birth not only to a new form of music but to a way of doing business, pioneering his own labels, running his own management agency, and controlling his own publishing copyright. He was a beacon of progress in an industry that had brutally exploited black artists for decades. Cooke was charismatic, ambitious and determined to control his own career, and so became a critical influence on Cassius and his thinking.

Since his early childhood Cassius had been taught the value of self-reliance. His father had lectured him on the teachings of Marcus Garvey and his mother had instilled in him a much simpler credo of good behaviour and crime avoidance. By the time he met Sam Cooke, there were numerous successful African-American businesses, in pharmacy, the funeral trade and local taxi firms, but it was in entertainment where the message of ownership and self-reliance was at its most dramatic. In the soul studios of Detroit and the gospel stores of Chicago’s Southside, Cooke and his contemporaries were very public exponents of taking control. It was a message that Cassius witnessed close-up and began to apply to his own life.

Most important of all his acquaintances was the squat Sam Saxon, a former pool-hall hustler who moved to Miami and ran the toilet and shoe-shine concessions at Hialeah Race Track in central East Side. Saxon was something more than a shoe-shine boy, though. He was a renowned street captain of the Nation of Islam, sent to Miami to recruit young men in the dilapidated streets of Overtown and to offer hope to the ex-prisoners from the ‘Flat Top’ in Raiford Prison who had drifted back to their old ghetto haunts. Saxon had been born and raised in a troubled community, in the John Eagan Homes Projects, a tough complex built for black families in Atlanta, Georgia. He had converted to Islam as a teenager and after intensive study won the accolade of ‘Rock of the South’, valued as one of the Nation’s most successful ‘fishers of men’. Sometime in March 1961, soon after Cassius had arrived from Louisville, Saxon made his first contact with the young boxer. It was a fleeting conversation at first, but they talked frequently thereafter, and it was Saxon who first invited him to abandon his slave name and adopt the temporary name Cassius X. They met for longer and deeper conversations in a darkened room, behind the sun-parched blinds of the Sir John Hotel, as guests and visiting soul musicians lounged by the pool. It was in these inauspicious settings that Saxon laid the first paving stones on Cassius’s path to Islam and his historic transformation into Muhammad Ali. Saxon, whose Muslim name was Abdul Rahaman, recounted the moment in some detail. ‘My job was to see that that the men in the Temple were trained to be good providers for their family, made physically fit, and taught how to live right . . . There weren’t many members who attended regularly. Realistically, in Miami there were only thirty . . . I met Ali in the March of 1961 when I was selling Muhammad Speaks newspapers on the street. He saw me, said, “Hello, Brother,” and started talking. And I said, “Hey, you’re into the teaching.” He told me, “Well, I ain’t been in the temple, but I know what you’re talking about.” And then he introduced himself. He said, “I’m Cassius Clay. I’m going to be the next heavyweight champion of the world.”’

After their chance meeting on a street corner on 2nd Avenue, Captain Sam and Cassius forged an unlikely friendship. On the day they first met, Saxon spent the afternoon looking through the boxer’s scrapbook, mostly cuttings from the Courier-Journal, his local newspaper back home in Louisville. ‘He was interested in himself and interested in Islam and we talked about both at the same time,’ Saxon remembers. ‘He was familiar in passing with some of our teachings, although he had never studied or been taught. And I saw the cockiness in him. I knew if I could put the truth to him, he’d be great, so I invited him to our next meeting.’ Cassius remembered his first day at the modest storefront mosque and from the outset was nervous about the impact on his boxing. ‘For three years up until I met Sonny Liston, I’d sneak into Nation of Islam meetings through the back door. I didn’t want people to know I was there. I was afraid, if they knew, I wouldn’t be allowed to fight for the title but the day I found Islam, I found a power within myself that no man could destroy or take away. When I first walked into the mosque, I didn’t find Islam . . . it found me.’ ‘The first time I felt truly spiritual,’ Cassius told his biographer Thomas Hauser, ‘was when I walked into the Muslim temple in Miami. A man called Brother John was speaking and the first words I heard him say were, “Why are we called negroes? It’s the white man’s way of taking away our identity.”’

Race had shaped his young life. He had grown up against the backdrop of the most divisive civil-rights campaigns in modern times. During his impressionable teenage days in high school, he had lived through the lynching of Emmett Till (1955), the Montgomery Bus Boycott (1955–6) and the desegregation of Little Rock High School (1957). Then, as a young man training in Miami, he learned of James Meredith’s enrolment at the University of Mississippi (1962) and as he trained to fight Sonny Liston for the heavyweight title, a bomb blast at the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama, dominated the television news. By 1963 more than half the southern and border states were navigating the challenges of desegregation in the education system. Woolworths had announced that it would no longer operate segregated counters in its stores and the Howard Johnson company reported that of its 297 restaurants nationwide only 18 were still segregated.

Political change was palpable, but in the churches, recording studios and late-night juke joints, a more subtle revolution was underway, one that paralleled and commented on the story of civil rights but which also reflected the realm of the personal: love, romance, jealousy and betrayal. By the early sixties, the music of the African-American experience – jazz, the blues, gospel, R&B, doo-wop and pop – were starting to come together like tributaries into one great gushing river, becoming a new genre of music which became universally known as soul. It was the music of Cassius’s young life, and in those first days of the new music he became one of its most famous observers.

According to his younger brother and fellow boxer, Rudolph ‘Rudy’ Clay (aka Rahman Ali), the family had grown up in a comparatively sedate town: ‘Louisville was segregated, but it was a quiet city, very clean and peaceful.’ It was shaped by segregation but with none of the ugly and overt violent racism that one saw in Memphis or Birmingham, Alabama. The brothers grew up in a carnation-pink clapboard house with an overgrown lawn on Louisville’s West End, with a caring mother, Odessa, whose Baptist religion shaped their younger days. One magazine feature described Odessa Grady Clay as ‘a sweet, pillowy, light-skinned black woman with a freckled face, a gentle demeanour and an easy laugh. Everyone who knew the family in those days saw the kindness of the mother in the boy.’ She instilled in Cassius a love for the soaring gospel singers of his infancy and with no great success she tried to cajole her sons into joining local choirs.

His father Cassius Clay Sr was very different. An artist with some talent who painted murals for local churches, his name was often abbreviated to ‘Cash’. He was a garrulous man, mostly funding the family income through his job as a commercial sign-writer. ‘Odessa gave Cassius Jr. her kindness and generosity,’ writer Dave Kindred claimed; ‘the father was the son’s wellspring of manic energy and sense of theatre.’ Although Cassius’s father was arrested twice for assault and battery, he was a strict but far from violent man who showed no great interest in boxing. He was known locally as something of a fantasist, occasionally dressing as an Arabian sheik or Mexican peasant, and exuded a showiness that his son adopted. His younger son Rudy once described their father as having ‘a showman’s spark’. Cash’s most notable feature was a thin, black, sabre-styled moustache which earned him the nickname ‘Dark Gable’, and he was a well-known character in Louisville’s black bars, jazz nightclubs and pool halls. It was his father who first ignited Cassius’s interest in racial politics – tucked away in the family sideboard was his father’s membership of Marcus Garvey’s Universal Negro Improvement Association, the first significant black nationalist movement. Cash tried to influence his sons to pursue the road of self-reliance but he was not a fan of boxing and deep down he wanted Cassius to follow in his footsteps, pursuing art, cartography and flamboyance.

Cassius’s parents were a coalition of opposites. According to biographer Jonathan Eig, his father was an extrovert, his mother more reserved. ‘He was rambunctious; she was genteel. He was tall and lean; she was short and plump. He railed against the injustices of racial discrimination; she smiled and suffered quietly. He was a Methodist who seldom worshipped; she was a Baptist who never missed a Sunday service at Mount Zion Church. He drank and stayed out late; she stayed home and cooked and cleaned. Yet for all their differences, Cash and Odessa both loved to laugh, and when Cash teased her or told his stories or burst into song, Odessa would release herself completely in a beautiful, high-pitched ripple that helped inspire her nickname: ‘Bird’. Cassius’s mother was a formidable gospel singer, never pushy enough to sing professionally, but one of the Deep South’s expansive conservatoire of devoted church singers. His father was more attracted to jazz, jump-blues and anything that aroused the crowds in local nightclubs. So the family, like many before and since, straddled the great divide between the Lord and late-night entertainment: the breeding grounds of soul.

Back home Cassius had attended Central High School, where he was a below-average pupil. One of his early girlfriends, McElvaney Talbott, now an author, journalist and educator, who was in the same class as his brother Rudy Clay, remembers Cassius shadowboxing in the school corridors as he made his way from one class to the next. He was smart but never applied himself in school. ‘He was a cutup,’ she told The New York Times. ‘I just remember he was a lot of fun.’ His enthusiasm was boundless; each day he would try to beat the school bus, racing along the sidewalk as his peers cheered him on. Cassius was a show-off, a prankster and a hurricane of practical jokes. In a later era, his antics might have been diagnosed as an attention deficit disorder, but the more his hyperactivity was channelled into pummelling the punchbag, training with skipping ropes, and sparring in the ring, the more it was subsumed into ritual and routine. Sports Illustrated once referred to him as ‘an original, sui generis, a salad of improvisations – unpredictable, witty, mischievous, comical,’ whereas his senior-class English teacher, Thelma Lauderdale, described him as a daydreamer. ‘Most of the time, when he wasn’t paying attention, which was often, he’d be drawing . . . But he never gave me any trouble. Shy and quiet in my class. Meditative.’

Cassius was never a successful school student. Another New York Times reporter, Gerald Eskenazi, having been impressed by the young boxer’s ingenuity, quick wit and loquaciousness, remembers the sense of disbelief that Cassius failed the low level of attainment necessary to join the US Army. Dumbfounded, Eskenazi called the principal at Central High School looking for clarity. ‘He revealed to me that Ali’s IQ was 78. That’s right, the most irritating, charming, irascible athlete in America, someone quoted every day, already a world-wide figure, had an IQ that was 22 points lower than the norm,’ he wrote. He also disclosed that Cassius had ranked 367th in his high school class of 391 students. The principal explained that it wasn’t unusual for young black students to do poorly in a test designed for white kids, and that Ali was someone who got nervous when he had to take a test. (What the principal failed to say was that the students who surpassed him were black too.) It was a nervousness he tried to mask with flashy self-confidence.

At high school, Cassius had been a novice skater, attracted to the rink for teenage friendship more than sport. He was friends with his fellow boxer, the quiet and overshadowed Jimmy Ellis, the son of a local cement labourer turned Baptist minister, who had once beaten Cassius as an amateur. Jimmy Ellis was an easy man to like, not only because of his humility and his tolerance of Cassius’s bragging but because of a deeply held spirituality. He was one of many great singers who stayed devoted to gospel and refused to move over to soul music; for much of his young life he was a featured tenor singer in the Riverview Spiritual Singers, one of Louisville’s top gospel acts. Ellis eventually signed a recording deal with Atlantic Records.

Another junior high-school friend was the soul singer Buford ‘Sonny’ Fishback, who throughout much of his career sang under the name Sonny Fisher. His early career captures some of the seismic changes that he and Cassius were exposed to. While still a starry-eyed teenager, Fishback, also an accomplished church singer, began performing in Louisville bars. He dropped out of school and ended up working in local nightclubs alongside older musicians at the Top Hat, Charlie Moore’s, the Crosstown Café and the Diamond Horseshoe. Fishback eventually came under the influence of the notorious Don Robey. Some of the major gospel artists of the day were shelving their Christian obduracy and crossing over to more commercial forms – rock ’n’ roll, R&B and the secular love songs of doo-wop – and Robey was waiting for them. Robey was a scheming master of the devil’s music and the owner of the famous Peacock Nightclub in Houston, Texas. Like many pioneers of the first generation of independent labels, Robey was a vaporous character who was known to cheat his artists by stealing their copyrights and using strong-arm violence on those who resisted. His famous Duke-Peacock group of labels reflected the changes that music was ushering in, and Fishback would end up recording for Peacock in 1967.

Fishback left Louisville when Cassius moved to Miami. He seems to have had a peripatetic career, trying to make his way through the maze of small independent labels that were sprouting up in black neighbourhoods. Like many aspiring soul singers, he moved north to Harlem to be in touching distance of the bigger black-music indies – Atlantic, Wand, Calla and Fat Jack Taylor’s Tay-Ster Records – staying there for nearly twenty years while recording for labels that were nominally based in Houston, New Orleans, Chicago and Los Angeles. Most significantly, Fishback recorded for Allen Toussaint’s Tou-Sea Records in New Orleans and was the voice behind the pounding underground R&B record ‘Heart Breaking Man’ (Out-A-Site, 1966). His fitful career in the independent soul scene finally stalled and he was incarcerated for a series of crimes, eventually returning to Louisville to reconnect with the Christian gospel roots he had left behind. He is now a flashily dressed widower, tour co-ordinator and a local civil-rights activist who claims that even from childhood, Cassius was anointed with a special gift, ‘the power of words’.

Another one of Cassius’s contemporaries was the jazz-soul musician Odell Brown, a virtuoso organist whose band Odell Brown and the Organizers performed locally in Louisville. After being drafted into the military, and a short spell in Vietnam, in 1966 Brown’s group won Billboard’s ‘Best New Group’ award. He graduated to become a staff musician at the Chess Records Studios in Chicago where he worked with the great Chess school of blues and soul musicians, among them Muddy Waters, Howlin’ Wolf, Rotary Connection, Ramsey Lewis and the underground duo Maurice and Mac. Their paths occasionally crossed on the road as Cassius’s career soared and Brown was working as the musical director for standout Chicago artists like Curtis Mayfield and Minnie Riperton. Odell Brown was one of soul music’s great tragedies. In 1982 he co-wrote ‘Sexual Healing’ with Marvin Gaye, but a year later, after a period of deep depression, he was living in a skid row hotel in Los Angeles. When the Grammy Awards were on television, he was sitting in a bar watching, despite being nominated four times and winning the category for best R&B instrumental for ‘Sexual Healing’. He told a stranger next to him that he’d just won a Grammy and the stranger understandably responded: ‘Yeah, right.’

Despite his woeful academic record, Cassius wove many myths around his teenage years. There was the stolen bike that led to a chance meeting in the city’s Grace Community Centre, where a local policeman, Joe E. Martin, guided him to the Golden Gloves Championships. There was his gold medal victory at the Rome Olympics, which supposedly ended with Cassius throwing the medal into the Ohio River after he had been refused entry to a white-owned restaurant in Louisville. It was a story that resonated in the era of civil rights and one he told repeatedly, but it has become the subject of much speculation. His brother, Rudy Clay, is adamant the story is true and has always claimed the incident happened near a burger restaurant and that Cassius threw the medal into the torrents of the river. Others have claimed he still had the medal two years later in Miami and often flaunted it to the kids who followed him on the sidewalks of Overtown, and Sam Moore claims he saw him wearing the medal round his neck like a pendant as he strolled the hotel corridors by the entrance to the Knight Beat club. He may well have been mistaken, and the myth of the gold medal has thrived on the back of claim and counter-claim.

Cassius made his professional debut in October 1960 in the Freedom Hall State Fairground, at the local Louisville Arena, where he defeated Tunney Hunsaker on a unanimous points decision. Cassius had been training locally at Bud Bruner’s Headline Gym and supposedly arrived at the Fairgrounds in a pink Cadillac, an idea he had copied from the Harlem-based boxing star Sugar Ray Robinson. He had not earned any money to afford a car, let alone a pink Cadillac, and so the most likely explanation is that his equally flamboyant father had hired it for the day. It was one of the first of many showy statements that Cassius would display in the years to come. Bizarrely, his opponent, Hunsaker, was the more newsworthy of the two in the folksy way that attracts attention in local media. He was the Police Chief of the small town of Fayetteville, West Virginia, and had taken leave from his police duties to travel to Louisville. Hunsaker earned a pitiful $300 for the fight while Cassius had negotiated a purse of $2,000.

After the fight Cassius signed an $18,000 contract to be managed by a consortium of eleven Louisville businessmen, a crucial move that secured his credibility in the early years. In contrast to many of his opponents, The Louisville Sponsoring Group were mostly distinguished citizens who, unusually for heavyweight boxing, had no known criminal connections. Ten of the members of the consortium were millionaires, and each invested $28,000 to back Cassius. The deal was signed off by Cassius’s lawyer, the formidable Alberta Jones, the first female African-American prosecutor in Louisville, Kentucky. Jones stipulated that 15 per cent of Cassius’s winnings should be held in a trust until he turned thirty-five, an enlightened negotiating point in a sport that paid primarily hand-to-mouth, with a horrific track record of impoverished, washed-up and brain-damaged ex-fighters. Jones was a civil-rights advocate who was active in her community as a member of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and a prominent figure in the voter-registration movement. She was subsequently appointed to the Louisville Domestic Relations Court, where she was a prosecutor on behalf of abused women. In 1965, Alberta Jones was beaten, murdered and thrown into the Ohio River. It was first assumed that she had drowned but blood was found in her abandoned car near the Sherman Minton Bridge, and witnesses claim they saw three unidentifiable men throwing something or someone into the river. Police reports suggest she may have been dumped from a boat ramp, but her purse was not found until three years later, near the bridge. Many theories exist as to who the killer or killers were, yet the case remains unsolved. The fingerprints of a young seventeen-year-old local boy were found on Jones’s car but no substantial case could be built against him and the investigation drove into the sand. Two theories have predominated ever since: that she was killed by a white supremacist group retaliating against her civil-rights work, or that she was a victim of a Nation of Islam assassination squad, at a time when the organisation was seeking to exert legal control over Cassius’s boxing career. Neither theory has ever come close to being verified.

In his adolescence, long before he left Louisville, Cassius had become fascinated by the myriad of dance craze records that were then sweeping the pop charts. The shifting rhythms and the daft incantations of dance craze sounds chimed with his own gregarious style, and he was known to dance in the school corridors, turning, spinning and side-shuffling to the imagined beat. Dick Sadler, a trainer with the legendary boxer Archie Moore, claims that he spent a long and frustrating rail journey with Cassius, when Chubby Checker’s ‘The Twist’ and Dee Dee Sharp’s ‘Mashed Potato’ were dominating the national teen charts. According to Sadler, Cassius stood up in the train corridor, from Los Angeles to Texas, imitating the dances and singing novelty songs over and over again to the annoyance of fellow passengers. It was a hint at his hyperactive personality and the first signs of his growing fascination with music, a hobby he shared with his brother Rudy. Fame brought them into contact with many prominent stars in the years to come, and ironically, although the young boxer’s celebrity outshone almost all of them, he was visibly nervous, intimidated and in awe in their company.

His friend, the photographer Howard Bingham, who worked at the black newspaper the Los Angeles Sentinel when he first met Cassius, claimed that he was like a child in the company of R&B singers. He once said, ‘Ali loved Fats Domino, Little Richard, Jackie Wilson, Sam Cooke, Lloyd Price, Chubby Checker, all those guys . . . It’s like he’s still a kid, looking up, and they’re the ones on the pedestal.’

His fascination with musicians began long before he was famous. Late in 1958, Cassius was hanging outside Louisville’s Top Hat Lounge, on 13th and Walnut Street, owned by a corpulent local entrepreneur, Robert ‘Rivers’ Williams. Although his mother had banned him from going near the Top Hat, he supposedly broke through a crowd of well-wishers and introduced himself to the R&B star Lloyd Price, whose song ‘Stagger Lee’, about the adventures of a St Louis pimp, was about to storm the chart. ‘Stagger Lee’ became one of Cassius’s favourite songs, although the shady world it was set in was far from his own loving, relatively settled upbringing.

As Cassius’s self-confidence grew, so too did family concerns; his mother was particularly fearful that his flamboyance would lead to trouble, and in the hypocritical way that family discipline often works, his father was worried that some of his own wayward habits would rub off on his son. There was a powerful context to their concerns. When Cassius was only thirteen, the September 1955 edition of the celebrity magazine Jet had been delivered to the family home. Jet was a compact glossy publication which featured stories of black achievement and profiles of famous African-American stars from the worlds of sport, cinema and R&B music. The comedian Redd Foxx once described Jet as ‘the negro bible’, and for many households, it was a populist window on the emergence of soul music, civil rights and black self-improvement. For this groundbreaking issue of the magazine, which was referenced again and again throughout Cassius’s later teen years, Jet had broken with their normal diet of celebrity entertainment and carried a truly disturbing set of photographs of the mutilated and disfigured face of Emmett Till, a young Chicago teenager who had been abducted and lynched in late August 1955 during a summer vacation to his grandfather’s home near the township of Money, in the Mississippi Delta. Till had been accused of being over-familiar with a local white woman and was then brutalised by her family and friends. Historian David Halberstam has since described the photographs as ‘the first great media event of the civil-rights movement’ and the Reverend Jesse Jackson called it the movement’s ‘Big Bang’, an issue of savage social injustice that all reasonable people could rally around.

The editorial decision to run with the photograph at the height of the trial of Till’s killers was a masterstroke in magazine publishing and repositioned Jet