9,59 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Polygon

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

In 1969, among Harlem's Rabelaisian cast of characters are bandleader King Curtis, soul singers Aretha Franklin and Donny Hathaway, and drug peddler Jimmy 'Goldfinger' Terrell. In February a raid on tenements across New York leads to the arrest of 21 Black Panther party members and one of the most controversial trials of the era. In the summer Harlem plays host to Black Woodstock and concerts starring Sly and the Family Stone, Stevie Wonder and Nina Simone. The world's most famous guitarist, Jimi Hendrix, a major supporter of the Black Panthers, returns to Harlem in support of their cause. By the end of the year Harlem is gripped by a heroin pandemic and the death of a 12-year-old child sends shockwaves through the USA, leaving Harlem stigmatised as an area ravaged by crime, gangsters and a darkly vengeful drug problem.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Ähnliche

PRAISE FOR MEMPHIS 68: THE TRAGEDY OF SOUTHERN SOUL

Winner of the Penderyn Music Book Prize, 2018

Mojo – Books of the Year #4, 2017

Shindig – Book of the Year, 2017

‘Offers us a map of Memphis in that most revolutionary of years, 1968. Music writing as both crime reporting and political commentary.’

The Herald

‘Stuart Cosgrove’s whole life has been shaped by soul – first as a music journalist and now as a chronicler of black American music’s social context.’

Peter Ross, Sunday Herald

‘A trilogy of books by Stuart Cosgrove will become a vast tale of three cities, melding two of his great passions, soul music and American history. In Memphis 68 he continues his compelling account of the last tumultuous years of the 1960s as the decade of love shuddered to a halt in cities ablaze with civil unrest, race riots and political assassination.’

Sunday Post

‘It’s perfectly feasible that Stuart Cosgrove’s exhaustive, but briskly readable trilogy of social, political and musical histories of Black America in the late 1960s will go on to become deserved future classics . . . Cosgrove’s selection of his subjects is unerring, and clearly rooted in personal passion . . . The substance of the book is forensic and journalistic, but Cosgrove masks his wealth of detail beneath an authorial voice which is as easily, blissfully evocative as a classic soul seven-inch.’

David Pollock, The List

‘This is a book that grabs you from the off . . . If Detroit 67 was the first part of a three-act play, then Memphis 68 fulfils the role of the second act, where things get worse before they can get better, setting the scene perfectly for the denouement . . . There are few writers who so clearly and powerfully evince the relationship between popular culture and politics as he is doing with these books. Harlem 69 can’t come quickly enough.’

Alistair Braidwood

‘Highly recommended! Astounding body of learning. Future classic. Go!’

SoulSource.co.uk

‘As ever, Cosgrove’s lucid, entertaining prose is laden with detail, but never at the expense of the wider narrative. Hinging on that Memphis destination, he traces the savage dichotomy at the city’s heart: it was the site of multi-racial soul imprint Stax, but also the place where Martin Luther King was killed. A heartbreaking but essential read, and one that feels remarkably timely.’

Clash Magazine, Best Books of 2017

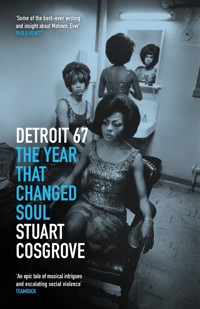

PRAISE FOR DETROIT 67: THE YEAR THAT CHANGED SOUL

‘Cosgrove weaves a compelling web of circumstance that maps a city struggling with the loss of its youth to the Vietnam War, the hard edge of the civil rights movement and ferocious inner-city rioting. His prose is dense, not the kind that readers looking for a quick tale about singers they know and love might take to, but a proper music journalist’s tome redolent of the field research that he carried out in Detroit’s public and academic libraries. It is rich in titbits gathered from news reports. It is to be consumed rather than to be dipped into, a whole-hearted evocation of people and places filled with the confidence that it is telling a tale set at a fulcrum of American social and cultural history.’

The Independent

‘Broadcaster Stuart Cosgrove lifts the lid on the time when the fight for civil rights and clash of cultures and generations came together in an incendiary mix.’

Daily Record

‘The set-up sparks like the finest pulp thriller. A harsh winter has brought the city to its knees. The car factories are closed and Motown major domo Berry Gordy is fighting to keep his empire afloat. Stuart Cosgrove’s immaculately researched account of a year in the life of the Motor City manages a delicate balancing act. While his love for the era – particularly the music, best exemplified by the dominance of Motown, whose turbulent twelve months are examined in depth – is clear, he maintains a dispassionate, journalistic distance that gives his epic narrative authority and depth. *****’

The Skinny

‘A gritty portrait of the year Motown unravelled . . . Detroit 67 is a wonderful book and a welcome contribution to both the history of soul music and the history of Detroit.’

Spiked

‘A thoroughly researched and fascinating insight into the music and the times of a city which came to epitomise the turmoil of a nation divided by race and class, while at the same time offering it an unforgettable, and increasingly poignant, soundtrack . . . By using his love of the music as a starting point he has found the perfect way to explore further themes and ideas.’

Alistair Braidwood

‘The subhead for Stuart Cosgrove’s Detroit 67 is “the year that changed soul”. But this thing contains multitudes, and digs in deep, well beyond just the city’s music industry in that fateful year . . . All of this is written about with precision, empathy, and a great, deep love for the city of Detroit.’

Detroit Metro Times

‘The story is unbelievably rich. Motown, the radical hippie underground, a trigger-happy police force, Vietnam, a disaffected young black community, inclement weather, The Supremes, the army, strikes, fiscal austerity, murders – all these elements coalesced, as Cosgrove noted, to create a remarkable year.

In fact, as the book gathers pace, one can’t help think how the hell did this city survive it all? In fact such is the depth and breadth of his research, and the skill of his pen, at times you actually feel like you are in Berry Gordy’s office watching events unfurl like an unstoppable James Jamerson bass line. I was going to call this a great music book. Certainly, it contains some of the best ever writing and insight about Motown. Ever. But its huge canvas and backdrop, its rich social detail, negate against such a description.

Detroit 67 is a great and a unique book, full stop.’

Paolo Hewitt, Caught by the River

‘Big daddy of soul books . . . Over twelve month-by-month chapters, the author – a TV executive and northern soul fanatic – weaves a thoroughly researched, epic tale of musical intrigues and escalating social violence.’

TeamRock

‘As the title suggests, this is a story of twelve months in the life of a city . . . Leading black music label Motown is at the heart of the story, and 1967 is one of Motown’s more turbulent years, but it’s set against the backdrop of growing opposition to the war in Vietnam, police brutality, a disaffected black population, rioting, strikes in the Big Three car plants and what seemed like the imminent breakdown of society . . . Detroit 67 is full of detailed information about music, politics and society that engages you from beginning to end. You finish the book with a real sense of a city in crisis and of how some artists reflected events.’

Socialist Review

‘A fine telling of a pivotal year in soul music’

Words and Guitars

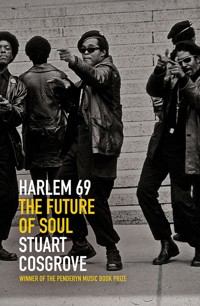

Two young kids stand in the doorway of 2026 Seventh Avenue in Harlem at the offices of the Black Panther Party, where breakfast programmes fed local children. The doorway is now that of Jenny’s Food Corporation, which sells chicken wings and French fries, and the address is 2026 Adam Clayton Jr Boulevard.

HARLEM 69

The Future of Soul

STUART COSGROVE

First published in Great Britain in 2018 by Polygon,an imprint of Birlinn Ltd.

Birlinn Ltd

West Newington House

10 Newington Road

Edinburgh

EH9 1QS

www.polygonbooks.co.uk

1

Copyright © Stuart Cosgrove 2018

The right of Stuart Cosgrove to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patent Act 1988.

All rights reserved.

Every effort has been made to trace copyright holders.

If any omissions have been made, the publisher will be happy to rectify these in future editions.

ISBN 978 1 84697 420 5

eBook ISBN 978 1 78885 025 4

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available on request from the British Library.

Typeset by 3btype.com

For Michael Tabor and Donny Hathaway

‘For the first time in years, he felt the deep sadness of exile, knowing that he was alone here, an outsider, and too alert to the ironies, the niceties, the manners, and indeed, the morals to be able to participate.’

—Colm Toíbín

CONTENTS

Foreword

January: Fat Jack Taylor’s Curious Empire

February: The Black Panther Conspiracy

March: King Curtis and the Ghetto Odyssey

April: Bitches Brew

May: Freddie’s Dead

June: Sophisticated Cissy

July: The Apollo Mission

August: The Black Woodstock

September: Return of the Voodoo Child

October: Prisoners of War

November: The Boogaloo Revolution

December: King Heroin

Epilogue: The Future of Soul

Bibliography

Index

FOREWORD

Harlem 69 is the final book in a trilogy of books on soul music and social change in the sixties. The two previous books – Detroit 67: The Year That Changed Soul and Memphis 68: The Tragedy of Southern Soul – focused on a specific place in an eventful year. Each of the books is self-contained and can be read independently, but read in sequence they tell a much bigger story of black music’s place in the many epoch-defining issues of the times: the evolution of ghetto sociology and culture in America; the civil rights movement; the emergence of Black Power; the assassination of the leaders of political change such as Malcolm X and Dr Martin Luther King; the war in Vietnam, both in South East Asia and on the home front; the impact of drugs and criminality on inner-city America; and how underground music became mainstream. This book is dedicated to two of its principal characters, the Harlem Black Panther Michael Tabor, a street kid who overcame heroin addiction to become one of the most influential street radicals of the sixties, and the great Donny Hathaway, one of black music’s towering geniuses, whose 1969 single ‘The Ghetto’ changed the direction of soul music.

What separates Harlem 69 from the two preceding books is its look to the future of soul. Rather than ending the trilogy on the final days of 1969, which would follow the logic of the decade, this book argues that Harlem in 1969 was the place where many of the seeds of soul music’s rich future were planted and nourished. The metaphor of creative growth in the ghetto was first imagined on the picture cover of Ben E. King’s song ‘Spanish Harlem’, in which a blooming red rose emerges from the cracks in a dilapidated Harlem sidewalk. It is self-evidently the rose of youth, of hope, of love, and, most importantly, of a new future. So, throughout the book you will meet soul in all its many emerging manifestations: jazz-funk, message music, psychedelic soul, disco and boogie, rare groove, house and hip-hop.

Inevitably, the trilogy focuses on the major labels of the era – Motown in Detroit, Stax in Memphis and Atlantic in New York – but all three books dig below the surface of commercial success and shine a light on independent labels and the artists who in many cases have been airbrushed from conventional histories of soul.

Writing the trilogy has been borne out of a lifetime passion which I hope comes across to readers. There are many people to whom I’m grateful. I’d like to thank the staff of Harlem’s Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, a research library of the New York Public Library and an archive repository for information on people of African descent worldwide; the Performing Arts Division of the New York Public Library and the archival staff of The New York Times. I’d like to thank the staff at my publishers Polygon, especially my editor Alison Rae and cover designer Chris Hannah, and I’m grateful to Michael Randolph for the use of his father PoPsie’s photograph of Wilson Pickett and Jimi Hendrix. Personal thanks to my dearest friends and family both living and dead. Finally, I’d like to thank my many friends on the rare and northern soul scene – the ultimate academy – whose collective knowledge and belligerent wisdom has informed the trilogy throughout. I owe a debt of gratitude to ‘the scene’ and all its eccentric characters. For those many people who have bought the two previous books, I hope this one lives up to your expectations.

Stuart CosgroveGlasgowSeptember 2018

Bearing gifts: Fat Jack Taylor dressed as Santa Claus at a Harlem children’s party in the early sixties. Taylor was one of Harlem’s most flamboyant characters; a heroin dealer, he was also the local boss of infamous indie label Rojac Records.

JANUARY

Fat Jack Taylor’s Curious Empire

Christmas was a fading memory for Fat Jack Taylor. He folded his Santa costume carefully and stored it away in his wardrobe for another year. The red coat reeked of alcohol and the tatty furry hat was discoloured with tobacco. Fat Jack briefly thought of taking it to the laundromat on 116th and Lenox, but it would be another year before the costume was needed so he doused it with cologne and closed the wardrobe door. When Fat Jack looked in his mirror it was always with a sense of disappointment. He had access to the latest gear – sharkskin shoes, cascading purple shirts and canary-coloured jackets tailored with the finest velvet edgings – but his face remained stubbornly round. Bulging rolls of fat crept up from his neckline, straining his top button and ruining whatever ensemble he tried on. He wore stylish Homburg hats and caused a commotion wherever he went but his greatest battle was neither with his rival heroin dealers nor the young soul singers who crowded hopefully around him: it was a fundamental anxiety he had fought since childhood – how to be both fat and fashionable.

Fat Jack was one of Harlem’s restless pioneers, an enigmatic figure who kept his private life close to his chest. He was a drug dealer and a tireless musical entrepreneur, boisterous with those who hung around him and confident that the next rising star would gravitate to him. He was in many respects a shepherd in wolf’s clothing, protective and threatening in equal measure. One of his most persistent routines was to clatter into his office on 116th Street and spend an hour among his young acolytes at Rojac Records, playing his way through piles of acetate discs or listening to promo records that had yet to hit the streets. It was a habit that had brought Fat Jack talent before anyone knew their names or, on several occasions, alerted him to fading stars of yesteryear, singers still clinging on to the life raft. He had worked out that those who were most in need of his services were either young and naïve or old and wasted.

In the early weeks of 1969 one particular record nagged at his mind, a standard lovers’ duet recorded in Chicago called ‘I Thank You Baby’ by June and Donnie. The song opened with a curiously poetic lyric, ‘Mama said thank you for the rain.’ It was a sound that appealed to Fat Jack and could have been recorded at any time in the sixties. He called the Chicago-based producer Curtis Mayfield to enquire about a national distribution deal but was rebuffed. He was told that the song had only materialised when Sam Cooke’s brother, L.C. Cooke, failed to show up for a recording session and, under pressure of time, Mayfield drafted in his colleague Donny Hathaway to partner local singer June Conquest. The record had already stalled, and having fallen out with Mayfield, Hathaway had moved to New York where he was staying on the fringes of Harlem not far from Fat Jack’s luxury apartment. He was now within touching distance, but within a year would be out of reach and one of the most talked-about musicians in black America. Hathaway’s era-defining single ‘The Ghetto’ would be stellar and his career would propel at a pace that was neither healthy nor sustainable. Hathaway was in need of medication, but way beyond the coke and dope that Fat Jack prescribed.

For much of the sixties, soul music had been dominated by Berry Gordy’s Motown empire in Detroit and the earthier Stax sound from Memphis; by contrast Fat Jack Taylor’s label never exerted the same influence but he was by some distance the most successful independent producer in ‘the capital city of black America’ – Harlem. As pop music diversified and took inspiration from the Summer of Love and psychedelia, Fat Jack’s label Rojac Records stayed hardwired to the streets, taking its influence not from world trends or international artists but from Harlem itself. Fat Jack had an unshakable belief that if anything was to change in music he would know about it first, because it would erupt in the streets he now called home: from the festering alleyways around Lenox, the impenetrable housing projects that lurked behind the Apollo Theater, or the impoverished teenage bedrooms of Harlem and the Bronx. He had seen it all before; the rest of the world might run out of energy but Harlem never would.

For much of the post-war period, Harlem was a magnet for musicians, offering opportunities in bars and nightclubs or as session musicians working on call for the Midtown studios. Although his origins are unknown, the most likely scenario is that Fat Jack was part of the great migration from the Deep South. Six million African-Americans had moved north from the largely rural communities of the South, first to escape slavery and segregation, but more often to seek out work in the industrial North, in Detroit’s bustling car plants and the processed-food plants of Chicago. Thousands flocked to New York and its myriad opportunities, joining the queue of hopefuls who saw the Apollo’s weekly talent competitions as a route to success. The Apollo was not only a magnet for the young and hopeful, it occupied a crucial place in the so-called Chitlin’ Circuit, the itinerary of mainly black venues that stretched across America. Most tours began or ended at the Apollo. It was a place of unrivalled opportunity but what few fully understood was the sheer scale of the competition. Harlem had become a graveyard for music’s might-have-beens: those walking corpses who found refuge in heroin, those who had given up and taken a low-paid job in public service, and those who simply hung around in the bars hoping to be remembered. Fat Jack knew them all and where they hung out. He could recite the dive bars and jazz joints as if they were old schoolmates: there was the Hi-Hat, the Baby Grand and the Palm Café; there was Mr B’s, Willie Abraham’s Gold Lounge and the Shalimar. He was guaranteed a seat wherever he went and he knew what secrets the barman hid beneath the counter.

Among the many musicians who had been abandoned in Harlem were two of Fat Jack’s associates, Bobby Lewis and Ritchie Adams, a couple of singers who had appeared at the Apollo with Jackie Wilson and the Fireflies. Having paid for their own travel from Detroit to New York, they were left penniless when Wilson’s entourage moved on, and so tried to earn a living by hawking their songs along Broadway. One of their most fruitful meetings was with Beltone Records, a start-up owned by producer Les Cahan and his studio director Joe René. Beltone had already secured a contract with the in-demand Harlem singer Chuck Jackson when, in an act of brinkmanship, Jackson insisted the contract was ripped up to allow him to join a better-resourced New York indie, Wand Records. In the hiatus Bobby Lewis and Ritchie Adams filled a vacuum with a string of solo R&B singles, as well as working in tandem with the doo-wop group the Jive Five. At almost exactly the same time, Fat Jack had found his way to the Beltone offices, where he sold them a song called ‘Peepin’ Tom’ (1960), which he recorded with a singer called Chuck Flamingo. The identity of Chuck Flamingo has never been established, and it’s possible, given Fat Jack’s capacity for deception and manoeuvring, that he may have successfully talked Chuck Jackson into breaching his newly signed Wand contract and moonlighting under the pseudonym. As Jackson’s career at Wand exploded, Flamingo’s records began to appear on the discount counters of the Acme supermarket chain, which at the time bundled discounted records into a bag known as ‘The Bag o’ 45s’. Humiliated that his debut single was being hawked in discount stores, Fat Jack bought up all the cheapskate bags and gave the records away as promotional gifts.

Between 1963 and 1970 Fat Jack’s drugs enterprise flourished. He was an O.G. – ‘original gangsta’ – one of the small army of high-ranking black drug dealers whose flamboyant names became etched in Harlem nightlife. Mookie Jackson, William ‘Goldfinger’ Terrell, Sylvester ‘Radar Man’ Hoffler, ‘Red’ Dillard Morrison and the notorious kingpin Bumpy Johnson were all part of a Harlem underworld engaged in a pathological business that was on the verge of spiralling out of control and bringing Harlem into national disrepute.

Unlike most of his flashy and heartless contemporaries, whose conspicuous consumption led them to jail, Fat Jack diverted much of his drugs profit into music; he released over fifty singles, many on labels that were misspelt and garishly designed. It may well have been his loss-making music ventures that kept the IRS at bay and allowed him to evade serious detection for years. Surreptitiously, Fat Jack bought up properties across Manhattan, eventually owning several luxury apartments in Riverside Drive, which variously became the gifted or sub-let homes of Big Maybelle, Etta James and, for a spell, the itinerant master guitarist Jimi Hendrix. Although his precious vinyl frequently stiffed, failure never dented Fat Jack’s boundless enthusiasm and, regardless of their obscurity, he paraded his artists around the ghetto as if they were superstars. He instinctively understood one of the most basic unwritten rules of the music industry and rewarded the talent with attention, gifts and glassine wraps of the very best brown sugar in Harlem. He kept the talent happy.

Unlike Motown and Stax, who dominated the soul charts in the sixties, it was a cause for celebration if one of Fat Jack’s singles scraped into the Top 100 – and a few did, most triumphantly Big Maybelle’s cover version of the garage band hit ‘96 Tears’, which grazed the Billboard pop charts in 1967, helped by an introduction shamelessly stolen from the Four Tops classic, ‘I Can’t Help Myself’. But the odds were stacked against Rojac Records; the label struggled for national attention in an industry still inured against independent soul and both corrupt and biased towards the majors. Nonetheless, being hardwired to the local community had distinct advantages. Rojac released records that screamed of the street and captured the extraordinary urban zeitgeist of Harlem.

Fat Jack was no conventional heroin dealer; his moral code is hard to define and he came shrouded in ambiguity. A man who profited from drugs, he poured resources back into local charities, block association events and initiatives that fed the homeless. For two decades he funded the annual Thanksgiving Dinner for the poor and homeless, using his fast food restaurant Soul Expression as the nerve centre of a charitable effort that spread throughout Harlem and into the Bronx. He was regularly cast as a black Santa Claus at children’s Christmas parties, and when big-ticket boxing bouts were fought at Madison Square Garden and Las Vegas, he would fund nights out for soul singers, favoured staff and other Harlem fly guys.

Fat Jack was ashamed of his weight but referred to it constantly, introducing himself as ‘Fat Jack’ or ‘the Fat Man’; he was acquisitive about credits, claiming he had written songs that were the work of others, but then he was fulsome in his praise of his artists; he was loud and gregarious when he entered a room, high-fiving and back-slapping, then would fade quietly into a corner with one or two close friends; he was a wealthy man who always carried greenbacks in his fleshy fists but he liked to give it away as much as to gain it, and frequently handed out gifts, loans and extravagant tips to people he barely knew. Most curious of all, he seems to have been asexual, happiest in the company of older R&B singers. He doted on Big Maybelle and at times was mistaken for her husband.

Of course he was a drug peddler in the most notorious areas of inner-city America and it would be easy with hindsight to cast him in a dark light, as sinister, exploitative and amoral, but the opposite seems to have been the case. The New York street paper Village Voice described Fat Jack as ‘a gentle behemoth’, a strange but accurate description of a man who was a lynchpin in the Harlem heroin trade but much liked, and who passed the time with those less well-off than himself.

Rojac Records and its sister label Tay-Ster (a name that was a conglomeration of Taylor’s surname and that of his sometime partner Claude Sterrett) were notable for the phenomenal range of their output, which reflected over twenty years of Harlem music. There was ‘Christmas In Vietnam’ (1966) by Private Charles Bowens & the Gentlemen from Tigerland, a brutally honest dispatch from the battlefield recorded by a group from Bowens’ regimental base in Fort Polk, Louisiana. Fat Jack loyally released the record on successive Christmases until patriotism stalled and the unpopularity of the war risked harming sales. Rojac released a party marijuana song called ‘Give Me Another Joint’ (1968) by Damn Sam the Miracle Man & the Soul Congregation; the pounding ‘I Love My Baby’ (1966) by the International ‘G.T.O.s’; Big Maybelle’s up-tempo ‘Quittin’ Time’ (1968); and Lillie Bryant’s uplifting ‘Meet Me Halfway’ (1966), a song that could have been hijacked from the Motown vaults and packed into jukeboxes along Lenox Avenue. With each new release, Fat Jack lavished money on launch parties, some so expertly conceived that he boasted with some merit that he threw the most famous parties in New York. They even had their own name – Fat Jack’s sets – a term which signalled their theatricality and the covert way they moved through Harlem, from storefronts to office lofts and community halls. For a man deeply implicated in the heroin trade, Fat Jack had a strange fascination with acting, the theatre and, most intriguing of all, opera, which is why his most successful record label – Rojac – carried the twin masks of tragedy and comedy as its logo. ‘There was a whole clique around Harlem,’ Lithofayne ‘Faye’ Pridgon told the Guardian newspaper in 2015. At the time she was one of Jimi Hendrix’s Harlem girlfriends and one of Fat Jack’s inner circle. ‘He was the dope kingpin of Harlem – he had everybody in his pocket . . . He was rumoured to be the dope dealer to all the stars . . . We would frequent the same kind of places and run into each other here and there, now and then. And there were always cute guys, cute girls, on the scene. Everybody was young and energetic. And so if you saw somebody you liked you kinda just . . . hooked up with them, took them with you.’ These spontaneous hook-ups usually took place at a hotel suite or at an apartment rented by Taylor. ‘You’d take the young tenders in and just party to your heart’s content. Sometimes a set lasted two or three days.’ And Fat Jack was the one who ‘always provided the finances, the drugs or whatever was necessary’.

In the spring of 1969 Fat Jack was planning a loft party to promote a slate of new Rojac releases, among them a reissue of a sadomasochistic funk song by Chuck-a-Luck & the Lovemen Ltd, snappily titled ‘Whip You’. The record had been out before, but Fat Jack had huge faith in it and was determined to make it a hit. Chuck-a-Luck had taken his name from an old Harlem dice game still played on ghetto street corners, but his real name was Little Charles Whitworth and he hailed from the Triad area of North Carolina. Whitworth had moved to Harlem after he toured Europe as Sam and Dave’s bassist, on the historic Stax tour of Europe two years earlier.

There was already a buzz about the night. Fat Jack had sent embossed invitations to the Apollo and they were laid out in the dressing rooms of that month’s roster of artists. Most of them were in town from Chicago – Gene Chandler, Tyrone Davis, Barbara Acklin, and the Chi-Lites featuring vocalist Eugene Record. He had tracked down Donny Hathaway’s home and left an invite there but it lay unopened.

Fat Jack’s big idea was not his best but it had audacity. He had told his inner circle to scour Manhattan for leather whips, which he planned to distribute to party guests on their arrival. Fat Jack had an eye for drama and he had put the word out that Harlem’s painted ladies should dress to impress, and that the ‘sophisticated cissies’ who hung out in the bars on Lenox were more than welcome. He liked gay men and had predicted the impact of gay disco before the term was in common use downtown. He had a passion for the great soaring gospel voices of the past allied to party music. In 1968 he signed the Cleveland vocalist Kim Tolliver and then Joshie Jo Armstead, a Mississippi singer who had relocated to Harlem after struggling to make an impact in the fiercely competitive downtown New York music industry.

In a gesture of largesse, Fat Jack had hired a private jet to bring in his Detroit business partners, mostly drug dealers, soul music contacts and rival label owners. Prominent among them was the Motor City producer Dave Hamilton, a one-time member of the legendary Funk Brothers and a talented guitarist who released records on the Motown subsidiary Workshop Jazz. Hamilton became Fat Jack’s most gifted collaborator and co-producer. It was through Hamilton that he became involved with a generation of talented singers who had slipped through Motown’s net, among them Little Ann, Tobi Lark and a gospel singer who would eventually relocate to Harlem to become Fat Jack’s trusted lieutenant and bodyguard, O.C. Tolbert. With Tolbert’s pure soul voice and Taylor’s instinctive feel for the street, they went on to produce an album that was destined to become the ultimate underground classic, Damn Sam The Miracle Man And The Soul Congregation, a rousing compilation of meandering jazz, madcap lyrics and hardcore funk that became a template for the music of Parliament, Funkadelic, Bootsy Collins and other insane street warriors yet to come. For much of 1968 he lived in rented property in Detroit where his Harlem-born runner Li’l Buster Robinson and a former Harlem Globetrotters star, Ernie Wagner, had set up his Detroitbased heroin operation.

Fat Jack was keenly aware that his party sets helped to promote records and sell drugs but most of all they brought him status. Harlem had a long and fascinating history of illegal or unlicensed parties, which ran through the night and into the next day, often emptying with the church bells. It was through parties, as much as the famous uptown clubs, that music made its atonal journey from ragtime to jazz to R&B and on to street funk. Sets were one of the links that connected back to the twenties, a period of intense creativity. The famous Harlem Renaissance – or as it was more commonly known then, the New Negro Movement – unlocked a spirit of freedom as the jazz age adjusted to the restrictions of Prohibition. Clubs became more secretive, more subterranean and more word-of-mouth, lending them a special allure for music lovers and white visitors from downtown. A network of parties began to flourish in tenement basements, in upstairs lofts, in storefronts, and even in the function rooms of Harlem’s once spectacular hotels. It was the area of ‘rent parties’ – illegal all-night drinking dens – where a small entrance fee of twenty-five cents helped the home-owners pay for their rent during a period of escalating costs and discriminatory land practices. Underground house parties were so common in the thirties that the superstar of the Harlem Renaissance Langston Hughes collected the ‘calling cards’ that were issued to promote the parties. On the surface they were polite and deceptively twee: ‘Satisfy Your Souls and Let the Good Times Roll at Joe Baker’s Social Whist, Apartment 3-11, 305 West 150th Street. Refreshments served’; ‘The lights are low, the music is fine, come on up and cop a tough grind with Elvira, Shirley and Barbara at Apt. 8. 2375 8th Avenue. Ring one long bell’; ‘Why stay at home and look at the wall, come out and let’s have a ball, at a party given by the 7 Brothers Social Club. Good music and refreshments. 2254 5th. Ave between 137th and 138th Street’; ‘Fall in line, and watch your step, there’ll be lots of browns and plenty of pep. A social whist given by Lucille and Minnie, 149 West 117th Street.’ But these coded invitations were fully understood by the bohemian Harlem community: ‘refreshments’ meant liquor, ‘grind’ referred to the latest sexually explicit jazz and blues tunes, and ‘browns’ and ‘pep’ meant heroin and amphetamine. This Harlem subculture of illegal parties preceded New York’s underground club scene, the UK’s northern soul all-nighters and the technorave scene by over forty years. By 1969 Fat Jack was the grandmaster of the secret venue, and his invite-only events had morphed into spectacular loft parties.

Harlem’s underground party scene was paralleled by another forerunner of club culture, a network of places not formal enough to be commercial venues like clubs or theatres where music was not simply played, but eulogised. Among them was Niggerati Manor, the brownstone rooming house on 136th Street that became the lawless home to the writers of the Harlem Renaissance and their short-lived magazine, Fire!!. One resident, the writer Bruce Nugent, painted giant multicoloured phalluses on the wall and encouraged gay bacchanalia into the small hours. In 1926 the drama critic Theophilus Lewis described it as a place of delirium and debauchery: ‘Those were the days when Niggerati Manor was the talk of the town. The story got out that the bathtubs in the house were always packed with sour mash, while gin flowed from all the water taps and the flush boxes were filled with needle beer. It was said that the inmates of the house spent wild nights in tuft hunting and in the diversion of the cities of the plains and delirious days fleeing from pink elephants . . . Needless to say, the rumours were not wholly groundless; where there is smoke there must be fire. In the case of Niggerati Manor, a great deal more smoke came out of the windows than was warranted by the size of the fire in the house.’

Another place that came to inform Harlem folklore was the riotous home of A’Lelia Walker – a black society hostess and patron of the arts whom the writer Langston Hughes called ‘the joy goddess of Harlem’s 1920s’. Her brick and limestone house at 108–110 West 136th Street near Lenox had a converted floor called the Dark Tower, a cultural salon that became legendary as one of the gathering places of ragtime, jazz and blues musicians. Hughes was a regular and described it as a place where sobriety was an unwelcome stranger. ‘A’Lelia Walker had an apartment that held perhaps a hundred people,’ he wrote. ‘She would usually issue several hundred invitations to each party. Unless you went early there was no possible way of getting in. Her parties were as crowded as the New York subway at the rush hour – entrance, lobby, steps, hallway, and apartment a milling crush of guests, with everybody seeming to enjoy the crowding.’ But the parties at the Dark Tower came to an end with the onset of the Great Depression. Antiques and luxury items were auctioned off, and in the early hours of 16 August 1931, after hosting a birthday party for a friend, A’Lelia Walker, Harlem’s irrepressible hostess, passed away.

Harlem’s list of secret venues was legend. Harry Hansberry’s Clam House on 133rd Street was the residence of the transvestite blues singer Gladys Bentley, whose recording career, in part fortified by her dynamic cross-dressing, was backed by the legendary OKeh Records. Bentley was a forerunner of the soul singer Clarence Reid aka Blowfly, who in 1968 had forsaken his Florida base and his own indie label Reid Records and was living in Harlem, recording for Dial and Wand Records, before he joined Fat Jack at Rojac. Separated by decades, both Bentley and Blowfly specialised in doing bawdy and sexually explicit cover versions of the popular hits of the day. Reid had unsuccessfully tried to convince Fat Jack to release his puerile show-stopping version of ‘Shitting On The Dock Of The Bay’, a gross parody of the late Otis Redding’s song. His ability to impersonate the greats of soul music was renowned in Harlem and Miami, but it was a blessing and a curse. He was so good at descanting on the voices of the famous that for years he struggled to promote a style of his own.

Since 1963 Fat Jack’s sets had borrowed from the historic Harlem underground. When he held a launch party for Rojac releases in 1967 and 1968 Blowfly performed and set out to shock the house with songs that were outrageous and anatomical, never missing a body part in the pursuit of laughs. Fat Jack prided himself on throwing the most lavish parties: a room drenched in blue neon, elegant crystal glasses, crushed ice, pure white cocaine, and, of course, throbbing street funk. His sets were a source of great personal self-respect, and it niggled away in his mind like an irritating put-down when the soul singer Benny Gordon told him about the writer and bon viveur Truman Capote throwing a party at the Plaza Hotel. Harlem and the high society scene in Midtown Manhattan were closed off to each other by race, class and social snobbery, and Gordon was the only connection between Capote and Fat Jack. Capote certainly knew nothing of the ghetto or soul music; in fact he had hired Gordon because he fronted the house band at a celebrity nightspot, Trude Heller’s discotheque on Sixth Avenue in the Village.

Truman Capote’s Black and White Ball was held at 10 p.m. on Monday, 28 November 1966 and became a defining moment in the rise of New York celebrity. Sinatra was there; so was Tallulah Bankhead and old Rose Kennedy. The party had been thrown in honour of Katharine Graham, the society hostess and president of The Washington Post. The newspapers christened it ‘The Party of the Century’ but Fat Jack insisted that none of the guests had ever ventured up to Harlem. The hardened soul communities of the ghettos and the privileged elite of Manhattan may as well have been millions of miles apart. Yet Harlem was in touching distance of what the mayor of New York, John Lindsay, had called the ‘silk-stockinged districts’, swathes of expensive homes on the Upper East Side and Central Park, which had a long tradition of electing well-heeled liberal Republicans, and where the managers of the advertising and music industry mainly lived.

Describing Fat Jack and Truman Capote as a clash of cultures would be to seriously underplay the gulf of difference. Only six people had ever bridged the two worlds and they were Benny Gordon and the Soul Brothers. At the time, Gordon was living in Bedford-Stuyvesant, Brooklyn, running the northern wing of Estill Records, a cash-strapped indie from his hometown of the same name in South Carolina. He had first met Fat Jack when he arrived in Harlem with his cousin Sammy, as part of the southern gospel caravan group called the Harmonizers. Just days after they arrived in Harlem, they played the Apollo, and, desperate for cash and exposure, secured a return booking by changing their name to the Soul Brothers, thus conning the management and reappearing as a new act.

Staying one step ahead of the law, Fat Jack rented or bought business premises across Harlem, shifting his main address almost annually, and used them as fronts for his labels and as temporary business dropboxes. Besides drugs, his biggest source of income was not music, it was fast food. He owned Fat Jack’s Chitlin’ House, a broiled chicken and southern soul food restaurant, which he frequently talked about franchising but never did. What is difficult to reconcile with Fat Jack’s drug empire and gangster lifestyle was his uncanny ability to spot talent on his doorstep. Like the Dickensian character Fagan in Oliver Twist, he had a coterie of young boys who buzzed around him like bees; some were orphans from the streets, some were attracted to him in the hope of money or fame, and some simply saw him as a generous father figure. It would be easy with hindsight to characterise Taylor as a predatory figure, preying on the young for his own gain, except that the young people he attracted were smart young men, some of them fearsomely bright, and many talented well above their natural age.

Private Charles Bowens, who sang lead on ‘Christmas In Vietnam’, was conscripted in the early sixties. He had been a standout pupil in the Harlem public schools system, a successful debating champion and a YMCA charity volunteer. At sixteen, he was nominated for Harlem’s outstanding boy of the year. Another Harlem high school standout was Michael Tabor, a basketball star at Rice High School who had taken a job at Rojac delivering flyers and running errands. Fat Jack loved Tabor’s booming basso profundo voice and they often discussed recording songs in the style of Paul Robeson but for the Black Power generation. Nothing came of it, and as the sixties intensified Tabor drifted further north, to a storefront near 141st Street, the headquarters of the Harlem Branch of the Black Panthers. The year of 1969 marked his life in the most extraordinary way; within a few short weeks he would be under police surveillance and at the centre of one of the most controversial show trials in American legal history.

Tabor was not alone. Although conventional wisdom has portrayed Rojac Records as a label surrounded by gangsters, the vice-president was a hip young civil rights activist called Claude Sterrett, whose heavy spectacles made him appear more like a geek than a gunman. Sterrett had a macabre back story: he was the son of an infamous Harlem undertaker, who in 1953 had shot his wife in a dispute that dated back to a failed business in South Carolina. The family still lived together on 113th Street, making ends meet by embalming bodies. Sterrett had been marching with his friend James Meredith when the famous civil rights leader was shot by a sniper in Mississippi during the voter-registration demonstration ‘The March Against Fear’ back in June 1966. The march had the high-profile support of Martin Luther King and the comedian Dick Gregory, an Apollo regular, who on a trip to Harlem recommended Sterrett to Fat Jack.

Fat Jack’s young recruits became his surrogate family – none more so than Herman Robinson. Although there is no evidence of formal adoption papers, Taylor had taken care of the wayward teenager, who was known on the streets by his nickname ‘Li’l Buster’. Robinson was only thirteen and homeless when he met Fat Jack. He was given a job (below the legal age) at Fat Jack’s fast food restaurant in premises below his offices on 116th Street, a corner that was the bustling front for drugs connections. Unmarried and possibly yearning for another life, Fat Jack described Robinson variously as his son or his nephew. He was neither. Fat Jack persisted with the deception and became a protective father figure, promoting Robinson within the business and mentoring him until the dying days of 1969 when Robinson was caught up in a botched robbery at a bar and sentenced to ten years. Such were the historic threads of Harlem at the time that Li’l Buster Robinson was sent to Attica State Prison in upstate New York – a place seething with violence, brutality and overcrowding that was about to erupt into the history books. Records show that Robinson was the youngest inmate in Attica when a riot broke out on 9 September 1971. On the fifth day of the uprising, Governor Nelson Rockefeller ordered state troopers to take back control. More than 2,000 rounds of ammunition were fired over six minutes, and when the smoke cleared, twenty-nine inmates and ten prison officers lay dead, most of them shot during the raid. Robinson survived. He was in the prison hospital at the time recuperating from a burst appendix and witnessed the mayhem through a window; years later he acted as a witness for the families who subsequently sued the New York State authorities.

By far the most famous members of Fat Jack’s street family were his close lieutenants and sometime business partners, the identical twins Arthur and Albert Allen. In their vivid description of Fat Jack, they described him as looking ‘like the Ugandan dictator Idi Amin’ and, like Amin, a man who was prickly and self-conscious about his weight. In the rough and tumble of Harlem nightlife, he had learned to laugh off insults but kept a surreptitious ledger of those who pushed it too far. The Allen twins had been born prematurely on Valentine’s Day in 1946 and grew up in a brownstone block on 141st between Seventh and Eighth Avenue. As children they hung out at the Woodside Hotel where their father often drank in the hotel’s down-at-heel Victoria Bar. They ran errands for the high rollers, earning cheap change from jazz musicians too blissed out to walk to the convenience store for a box of matches. The Woodside was a decaying place which had long lost its grandeur but it was where Count Basie had performed ‘Jumping At The Woodside’. Even in 1969 it remained a favourite watering hole for old jazz cats. The Allens’ mother was a music teacher and skilled pianist but it was their father who exerted the greatest influence. He worked on the railways for the Pullman Car Company and was a member of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, a pioneering labour union that fought the thinly disguised master–slave conditions that black workers faced in Pullman cars in the Depression years. Dependent on tips to supplement a low basic wage, their father became an ardent civil rights supporter and a close friend of the union leader, A. Phillip Randall. His views on desegregation and community politics were common conversation in the Allens’ crowded home, and it was through the Harlem branch of the Brotherhood, rather than through the more visible Martin Luther King Jr, that the twins first came to understand the power of collective action. Both were keen bodybuilders and members of the Harlem Gladiators, and provided physical support to Fat Jack, but to call them bodyguards would be a disservice. They were among the most talented and far-sighted young musicians in Harlem and only when they had converted to Islam did they become known by their stage name, the Fantastic Aleems.

By 1964 the Allen family were living in the St Nicholas Projects on 129th Street, in the same block as the Harlem funk star Jimmy Castor, and for the first time the twin brothers were torn apart. Arthur had been shot in the back during the Harlem riots of 1964 – one of over a hundred injuries – and his incapacity ruled him unfit for military service. As the Vietnam War intensified, Albert was swept up in a military conscription drive that targeted inner-city ghettos and was sent to Vietnam aged seventeen. When he asked what to expect in the malarial jungles of Vietnam, Albert was told by a commanding officer, ‘Marijuana, partying and freaky young oriental women.’ He had witnessed them all two blocks from home at one of Fat Jack’s sets and was unimpressed. While one brother went to Vietnam, the other stayed behind and grew closer to Taylor, joining a great Harlem soul group called the International ‘G.T.O.s’, who recorded for Rojac. Like many harmony groups before – the Cadillacs, the Chevrons, Maurice Williams and the Zodiacs, and Dennis Edwards and the Firebirds – the International ‘G.T.O.s’ were named after one of the de rigueur automobiles of the era: the Pontiac GTO. The ‘G.T.O.s’ were in every respect the classic mid sixties soul group, not unlike the Four Tops. Lead singer Tommy Lockhart was upfront with a powerful falsetto voice that preceded the great lead singer of the Stylistics, Russell Thompkins Jr, by years. Arthur Allen was the group’s second tenor. The International ‘G.T.O.s’ played bars in Harlem but struggled to make an impact nationally, so Arthur tried again. This time they changed the group’s name to the Master Four, and Taylor released a ridiculously catchy novelty record, ‘Love From The Far East’, which employed cod-oriental tropes over a pounding Motown beat. Harlem’s innovation seemed limitless.

Within a year Albert was back in Harlem, his military uniform confined to the cupboard, and reunited with his brother. They joined a generation who took their influence from the wave of Muslim teachings sweeping Harlem in the wake of the assassination of Malcolm X and changed their names to Tunde’ Ra Aleem and TaharQa Aleem respectively. More than any of Harlem’s thousands of restless children, it was the Fantastic Aleems who came to map out the shifting cartography of soul music and make the connection between sixties soul, disco boogie and hip-hop. By the summer of 1969 they had become the local promoters of guitar superstar Jimi Hendrix and were his closest companions in Harlem. Years later, they became the creative force behind Fat Jack’s pioneering hip-hop venue Harlem World, which he bought in partnership with the Aleems and his one-time gangster rival Mookie Jackson. The venue was a vacant lot on the corner of 116th and Lenox near Fat Jack’s fast food joint, which had once housed a struggling Woolworth store. As you emerged from the bowels of the IRT subway at Lenox, the club’s stained white facade met you; scattered near the doorway, multicoloured parasols sat incongruously in the rain, as if a Sandals resort had opened in the ghetto.

Sensitive to the sounds he heard in the bars of 125th Street, Fat Jack was quick to recognise the merits of street funk, and – again without conspicuous success – released some of the best of the genre. Curtis Lee & the KCP’s ‘Get In My Bag’ was one among many tributes to Godfather of Soul James Brown, but one specific release, recorded in the dying days of 1969, screamed of Harlem’s creative intensity and the sheer weirdness of Fat Jack’s parties. Recorded in Detroit, Chico and Buddy’s ‘Can You Dig It’ opens with blaring police sirens and then the action kicks in. A tireless funk soundtrack carries you up from the crowded sidewalk through a loft window to a full-scale set, heavy with sweet smoke, the floor heaving with dancers and drag artists. Bodies gyrate to percussive cowbells as the room is filled with insane druggy lyrics that shift from southern soul food to space-walk nonsense and surreal half-spoken soliloquies that could have been parsed by George Clinton’s Funkadelic. This was new funk at its rawest – urban street music breaking free of the feelgood stranglehold that Motown held over mid sixties soul and pointing forward to decades of more disruptive music yet to come. ‘Can You Dig It’ was one amongst hundreds of new releases circulating in the stores of Harlem and Bushwick that summer, local indie vinyl that was testing the coherence of traditional soul music in the civil rights era.

Although Fat Jack – and his local contemporaries Paul Winley and Joe Robinson – struggled to take lo-fi independent soul music much beyond Harlem, they had one overwhelming advantage over their contemporaries in Detroit, Chicago and Memphis. The shifting rhythms and quixotic fashion trends of 125th Street were on their doorstep. Robinson described a phalanx of record industry executives sifting through his shelves, checking the action and jotting down titles as he tried to manage a bustling store, the speakers spilling out on to the sidewalk, the sounds competing with screeching traffic. Despite their limited resources, the Harlem indies – and the questionable characters who drove the local music market – became bellwethers of the evolution of soul and how its future was fragmenting and changing. Record industry executives, sometimes apprehensive about their safety, hung out in Harlem record stores, hoping to crack the codes of black music and anticipate the next big shift in the shuddering journey of R&B.

Fat Jack and his retinue were a familiar sight cruising 125th Street in his classic-style Buick Electra 225. (Although his records were at the cutting edge of new funk and street boogie, his personal tastes were more retrospective.) Harlem’s indies such as Rojac, Tay-Ster, Sprout and Winley Records were typically under-capitalised and lived from one release to the next, often funding records from the proceeds of other local businesses. Compared with New York’s most established Midtown labels, like Florence Greenberg’s Scepter/Wand group and the towering Atlantic Records, these were makeshift organisations, often existing in a twilight world closer to street crime than global distribution deals. Atlantic, the self-styled ‘West Point of Rhythm and Blues’, could boast the towering talent of Aretha Franklin and the recording catalogue of the late Otis Redding. Their roster of artists included Patti LaBelle, Wilson Pickett, Sam and Dave, King Curtis, Don Covay and both Roberta Flack and Donny Hathaway. Set against the established R&B labels which were already diversifying into the next generation of progressive rock, Fat Jack was reliant on cash derived from multiple questionable sources including illegal street gambling, the drug trade and vinyl bootlegging.

His relationship with the soul vocalist Big Maybelle was a bundle of intrigue. He was her manager, her producer and almost certainly her ‘doctor’, the intimate word that the declining and distressed R&B singers of Harlem used to describe their most trusted and reliable heroin dealer. But to describe their relationship as simply one of addict and dealer would be to diminish a bond that held fast for many years and was one of both love, artistic support and dependency. Fat Jack poured money into making her a star again, taking out adverts in Billboard to back her 1966 album Got A Brand New Bag and building a distribution team focused almost entirely on reviving her fortunes in stores across the US. It never quite came to anything, but their relationship lasted until Big Maybelle was too ill to continue working and was finally forced to leave Harlem. She returned to her mother’s home in Cleveland where she succumbed to diabetes, never able to shed weight or her drug dependency.

Fat Jack’s contradictory personality lurched from an intimidating hard exterior to an emotional soft core. He was considerably more sensitive to the shifting fortunes of his roster of artists than more established record producers and his advice to those around him was a coarse interpretation of Black Power – ‘Don’t let them intimidate you, intimidate them.’ He was admirably blind to age and to reputation, courting new artists with nothing more than an idea, and then the next day revivifying those whose careers were spiralling towards ignominy. He was a close confidant of Etta James and was with her when she recorded ‘Miss Pitiful’, her self-reflective cover version of the Otis Redding standard, ‘Mr Pitiful’. At the time of the recording in June 1969, James’s life was already seriously compromised by drug and alcohol problems. Rather than blame her supplier, the singer described Fat Jack as a saviour, a man who had protected her from the darkest forces of the recording industry.

He had also held out a hand of hope to a third great female singer, Joshie Jo Armstead, whose career had brought her to Harlem from a period as a recording artist at Giant Records in Chicago. Armstead befriended Nicholas Ashford and Valerie Simpson, then two budding songwriters from Harlem’s White Rock Baptist Church, and held their hands as she led them around the publishing companies of Midtown, until they were spotted by Motown and relocated to Detroit to become the chosen writers for Marvin Gaye and Tammi Terrell. Working as a threesome throughout the mid sixties, Ashford Simpson and their mentor Armstead wrote several great soul songs, not least Ray Charles’s ‘Let’s Go Get Stoned’ (1966) and another partially disguised drug-addiction song, ‘I Don’t Need No Doctor’ (1966). By then Charles’s career had stalled and he could often be found in the Woodside Hotel talking race relations with the Allen twins’ father William. He had been arrested for possession of heroin for a third time and was one among many major singers of the era facing rehab.

Heroin was not only gripping Harlem, it had travelled like a hurricane through R&B. In January 1969 Esther Phillips’s contract with Atlantic had expired. Frustrated by her unreliability, Atlantic let her go, and she signed to another New York indie, the notoriously uncaring Roulette Records. It was one of the many low points in her career. Ravaged by heroin addiction, she took the brave but risky decision to check herself in to the controversial Synanon clinic in Los Angeles, where she met the singer Sam Fletcher. Together they worked on a live album at the local Pied Piper Club. Phillips’ therapy was brutal in the extreme. Under the tough regime of the untrained Charles E. Dederich, she suffered for weeks in a former hotel in Santa Monica. Dederich, a reformed alcoholic, was one of the West Coast’s irrepressible fantasists who wanted to create an experimental cult that would transform the world. ‘Crime is stupid, delinquency is stupid and the use of narcotics is stupid,’ opined Dederich. ‘What Synanon is dealing with is addiction to stupidity.’ His programme rejected any form of pharmaceutical treatment, and Phillips, along with most of her fellow patients, suffered an unforgiving ‘cold turkey’. Those who visited the facility at the time described seeing junkies left on couches to writhe and vomit for days while they suffered withdrawal. Then they were confronted with ‘The Game’, a group therapy set-up where people sat in a circle barking their frustrations at each other. It was a ragbag of bogus science, half-digested psychology and punishing behaviourism. But by sheer fluke, rather than any underlying therapy, it worked for Phillips and she returned to her spiritual home at Atlantic. In 1972, on her painfully honest album From A Whisper To A Scream, Phillips recorded one of the era’s greatest self-critical heroin songs, Gil Scott-Heron’s ‘Home Is Where The Hatred Is’. A song of dramatic complexity, it recounts the personal experiences of a junkie walking through the ghetto twilight and trying to avoid returning to a broken home. As the song unfolds, memories of home and of domestic abuse intertwine with the rash of needle marks.

As Phillips headed optimistically to rehab in California, back in Harlem Fat Jack was also looking to the future. A new generation of musicians who did not share the great R&B and jazz lineage of Big Maybelle, Etta James, Esther Phillips and Ray Charles were hustling for attention. They were mostly young, untried and from the ghetto tenements of Harlem, earning cash working for Fat Jack’s string of businesses or dealing on his behalf on street corners.