Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Polygon

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

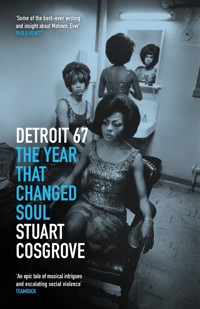

Spanning three different cities across the United States, Stuart Cosgrove's bestselling Soul Trilogy blends history, culture and music to paint a vivid picture of social change through the last years of the 1960s. Strap in for a journey through urban riots, escalating war in Vietnam, police corruption, the assassination of Martin Luther King, the rise of musical pioneers such as Aretha Franklin, Elvis Presley and Johnny Cash, the arrest of the Black Panther members and their controversial trials, and much, much more. Award-winning and critically acclaimed, these are books that no soul music enthusiast should be without. 'Cosgrove's lucid, entertaining prose is laden with detail, but never at the expense of the wider narrative' – Clash Magazine Titles included in this bundle are: Detroit 67 Memphis 68 Harlem 69

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 1972

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

THE COMPLETE SOUL TRILOGY

Stuart Cosgrove

eBook Bundle

Detroit 67Memphis 68Harlem 69

This eBook was first published in Great Britain in 2023by Polygon, an imprint of Birlinn Ltd

Birlinn LtdWest Newington House10 Newington RoadEdinburghEH9 1QS

www.polygonbooks.co.uk

Copyright © Stuart Cosgrove, 2016, 2017, 2018

The right of Stuart Cosgrove to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored, or transmitted in any form, or by any means electronic, mechanical or photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the express written permission of the publisher.

eBook ISBN 978 1 78885 632 4

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication DataA catalogue record for this book is available on request from the British Library.

‘Cosgrove weaves a compelling web of circumstance that maps a city struggling with the loss of its youth to the Vietnam War, the hard edge of the civil rights movement and ferocious inner-city rioting. His prose is dense, not the kind that readers looking for a quick tale about singers they know and love might take to, but a proper music journalist’s tome redolent of the field research that he carried out in Detroit’s public and academic libraries. It is rich in titbits gathered from news reports. It is to be consumed rather than to be dipped into, a whole-hearted evocation of people and places filled with the confidence that it is telling a tale set at a fulcrum of American social and cultural history’

The Independent

‘Broadcaster Stuart Cosgrove lifts the lid on the time when the fight for civil rights and clash of cultures and generations came together in an incendiary mix’

Daily Record

‘The set-up sparks like the finest pulp thriller. A harsh winter has brought the city to its knees. The car factories are closed and Motown major domo Berry Gordy is fighting to keep his empire afloat. Stuart Cosgrove’s immaculately researched account of a year in the life of the Motor City manages a delicate balancing act. While his love for the era – particularly the music, best exemplified by the dominance of Motown, whose turbulent twelve months are examined in depth – is clear, he maintains a dispassionate, journalistic distance that gives his epic narrative authority and depth . . . History is quick to romanticise Hitsville USA but Cosgrove is not quite so credulous, choosing to focus instead on the dark shadows at the heart of his gripping story. *****’

The Skinny

Online reaction

‘A thoroughly researched and fascinating insight into the music and the times of a city which came to epitomise the turmoil of a nation divided by race and class, while at the same time offering it an unforgettable, and increasingly poignant, soundtrack. With his follow-up, Memphis 68, on the way, Cosgrove is well set to add yet another string to his already well-strung bow, becoming a reliable chronicler of a neglected area of American culture, telling those stories which are still unknown to most’

Alistair Braidwood

‘The story is unbelievably rich. Motown, the radical hippie underground, a trigger-happy police force, Vietnam, a disaffected young black community, inclement weather, The Supremes, the army, strikes, fiscal austerity, murders – all these elements coalesced, as Cosgrove noted, to create a remarkable year. In fact, as the book gathers pace, one can’t help think how the hell did this city survive it all? In fact such is the depth and breadth of his research, and the skill of his pen, at times you actually feel like you are in Berry Gordy’s office watching events unfurl like an unstoppable James Jamerson bass line. I was going to call this a great music book. Certainly, it contains some of the best ever writing and insight about Motown. Ever. But its huge canvas and backdrop, its rich social detail, negate against such a description. Detroit 67 is a great and a unique book, full stop.’

Paolo Hewitt, Caught by the River

‘The subhead for Stuart Cosgrove’s Detroit 67 is “the year that changed soul”. But this thing contains multitudes, and digs in deep, well beyond just the city’s music industry in that fateful year . . . All of this is written about with precision, empathy, and a great, deep love for the city of Detroit’

Detroit Metro Times

‘Big daddy of soul books . . . Over twelve month-by-month chapters, the author – a TV executive and northern soul fanatic – weaves a thoroughly researched, epic tale of musical intrigues and escalating social violence’

TeamRock

‘Detroit 67 is full of detailed information about music, politics and society that engages you from beginning to end. You finish the book with a real sense of a city in crisis and of how some artists reflected events. It is also the first in a trilogy by Cosgrove (Memphis 68 and Harlem 69). By the time you finish this, you’ll be eagerly awaiting the next book’

Socialist Review

‘A gritty portrait of the year Motown unravelled . . . a wonderful book and a welcome contribution to both the history of soul music and the history of Detroit’

Spiked

‘A fine telling of a pivotal year in soul music’

Words and Guitars

CONTENTS

Heart and Soul

January: Snow

February: Crime

March: Home

April: Love

May: Strike

June: War

July: Riot

August: Ordeal

September: Surveillance

October: Collapse

November: Law

December: Flight

Bibliography

Author

Index

HEART AND SOUL

I want to acknowledge the help of those people who influenced Detroit 67 knowingly or otherwise: most of all my gratitude to the singers, songwriters, musicians and activists who shaped the highpoint of sixties soul. Over many years as a journalist frequently writing about soul music, I have met and interviewed many of the central characters in this book but would like to single out two. Mary Wilson of the Supremes, who I had the pleasure to interview at length live on stage at the Victorian and Albert Museum in London, and the late Jimmy Ruffin who shared with me his personal family perspectives about his father and brother; his accounts of his early life in the Deep South were moving in the extreme. I have tried to be as objective as possible about an era of music that has been the subject of wild myth-making and have tried throughout to see the complex events of 1967 in their context, rather than as a battle of good versus evil. Strange as it may seem there are very few books that touch on the story of Motown that have not tried to take sides in the premature death of Florence Ballard. I have resisted taking sides and try wherever possible to see merit in all the key characters, even when their young emotions were driving them forward.

In researching this book, I have been able to mine a wealth of primary resources. I acknowledge several academic institutions, including the Walter P. Reuther Library at Wayne State University in Detroit, which has a world reputation for labour affairs and industrial history. My thanks to the staff of my local library at the University of Glasgow in Scotland, who always made me warmly welcome. I drew heavily on the support of the staff and the primary sources of the Hatcher Graduate Library who provided most of the newspapers of the time and the Bentley Historical Library at the University of Michigan campus in Ann Arbor, Michigan, a specialist historical library which holds the Gordy Family papers, the personal papers of Motown publicist Al Abrams, and the private papers of Detroit radical John Sinclair. It also holds an inestimable collection of Detroit police files and photographs covering the riots of 1967.

I’d also like to acknowledge the influence and support of those underground ‘seats of learning’ that have formed such an important part of my life – my friends and contacts within the northern rare soul scene. I have had the lifetime privilege to be attached to a subculture which is not only engaged in a passionate love affair with black American music but has defied every attempt to tame that passion over several decades. My thanks therefore to the Universities of Soul that have helped me along the way: Perth City Soul Club, Wigan Casino, Blackpool Mecca, Top of the World, Stafford, and the 100 Club, London. It is impossible to convey to people outwith the scene how informed and analytical collectors on the northern scene are – they are the popular historians of soul music. This imprint of the book is what is known in the rare soul scene as the issue copy. In 2015, to test the potential for the book, it was self-published, or as record collectors would say it was released as a ‘private pressing’. But it had its faults, and by contrast, the quality of the book you have in your hand is more professional and the global distribution is of a different class to its predecessor. So, my sincere thanks to the phenomenal team at Polygon who made this version happen, including publisher Neville Moir, the passionate and relentless editor Alison Rae, and designer Chris Hannah.

Finally, I’d like to thank my colleagues at Channel 4 in London and Glasgow, and my colleagues at BBC Scotland for their support. Most of all I want to thank my close friends and family for their encouragement, their good humour and the hope that drives our lives.

© Gilles Petard/Redferns

The Whole World in His Hands. Berry Gordy, the owner of the Motown Corporation, poses in his Detroit home in 1966. At the time he was one of the richest African-Americans in the USA and the entrepreneurial figurehead of sixties soul. The photo was taken by a visiting French soul collector Gilles Petard.

JANUARY

Snow

Berry Gordy’s townhouse on the exposed corner of Outer Drive and Monica was trapped in a furious wind tunnel. A steep porcelain wall of drifting snow blocked the road outside, and two frozen trees hung heavy like sentries over the doorway. Gordy was reduced to the routine of a prisoner: pacing the room, speaking solemnly to himself, and looking out through the frosted windows at the white prison yards of his hometown.

A deathly silence had descended on the Motor City. Snow had fallen for three consecutive days, and it came with such fury that it smothered the life out of America’s busiest city. Suddenly, a city synonymous with the clamour of industry had grown eerily quiet. Most people hid indoors, guarding themselves from the cold and unable to dig a path to their cars, and those few brave souls who did try to get to work were left stranded on street corners, shrouded in military-surplus overcoats and blowing into woollen mittens. Others smoked to stay warm and huddled together, waiting for buses that never came. Cars were left abandoned in side streets, and the scene on Highland Park looked like something from a different decade, where wandering ghosts from the Great Depression stumbled across intersections to the old Ford assembly plant. Over 100,000 automobile workers reported absent from work, Dodge Main in Hamtramck was closed, Chrysler’s Eldon Avenue Gear and Axle Plant ground to a halt, and Ford’s giant River Rouge plant was on short time. A layer of dense smog hung over the stranded trains at Dequindre Cut, where rusting freight containers lay half hidden beneath the drifts. The newly installed furnaces at Huber Avenue Foundry had more than enough power to smelt steel, but the temperature stayed stubbornly below zero, and nothing could melt the snow. Schools were closed, flights disrupted, and the few reckless freighters that tried to navigate the frozen waters of the Detroit River or made only glacial progress to the lakes were impacted in ice.

Already a teenager when the Second World War broke out, Gordy had grown up in a restless and self-confident city driven by arms manufacturing and the automobile industry. In the years between 1940 and 1943, half a million people migrated to Detroit, and like the Gordy clan over 350,000 of those were African-Americans, mostly from the southern states. But all of that was history now.

Berry Gordy Jr was cut off from his world. He was thirty-eight years old, with a closely cropped afro that had infinitesimal specks of grey settling on the hairline, as if he had been momentarily caught in the blizzards outside. In January 1967 he was one of the richest black entrepreneurs in America and the driving force behind the Motown Record Corporation, the black-owned company that had defied the rules of the recording industry to become the powerhouse of sixties soul from an unfashionable base in the heart of the Rust Belt. In the previous fiscal year alone, over seventy-five per cent of the company’s releases had been hits, and Motown’s major acts – the Supremes, the Four Tops, the Temptations and Marvin Gaye – were international household names. It seemed to those who had watched his success that Gordy had discovered a modern form of alchemy on turning gospel into gold. By the time the Motown Corporation was incorporated on 12 January 1959, Detroit’s image as a boomtown was wearing thin, and the first corrosive signs of decline were beginning to show. Unemployment was rising, particularly among unskilled black males, many of whom were dependent on irregular shifts and low-paid labour in the car plants and armament factories. The underlying realities were plain to see, but the powerful myth of Detroit as ‘the arsenal of democracy’ overshadowed everything, and immigrants from the South still flocked northward to the city, believing that it was a placed paved with limitless opportunity.

Gordy had just returned home from Miami Beach, where the Supremes were in residency at the Deauville Hotel; he’d caught one of the last flights to land at a bitterly cold Metro Airport. The central heating in his Outer Drive home was turned up full blast, but it had next to no impact, and the cold was so fierce he had draped himself in layers of clothes: a poplin shirt, neat slacks with hip slit pockets, and a scruffy hooded sweater over his suit jacket. Two paintings of exotic palm trees hung on the wall above his piano. He had put them there to bring a touch of exotica to his home, but they looked forlorn and out of place.

Gordy was unaccustomed to silence. He had worked on the Detroit assembly lines, upholstering new cars, and had grown up with the endless percussion of the automobile plants. He had even trained himself to beat out tunes in his head, scribbling them in his mind and then recording them on paper when his shift ended. Gordy tried to fight the snowy silence at first by playing the piano, listening to acetate copies of newly recorded Motown songs, and flipping through the latest release sheets. His life had been shaped by vinyl. Records were stacked casually in the backseat of his car, piles of them lay scattered around his office, and those he really liked were stored in alcoves in his home. He had grown up surrounded by the sounds of the Motor City – the atonal journeys of jazz, the wholesome divinity of gospel, the hard-drinking coarseness of R&B, and the sweet choral repetitions of sixties soul.

To his friends and family, Gordy was a difficult man to fathom. He hid behind a contradictory personality, preferring the thrill of creativity to the managerial machinations of his wealthy business. He was a proud family man yet he played fast and loose with family values, playing poker, chasing other women and drinking hard liquor. From a young age he had come to romanticise the word ‘family’ – and used it promiscuously to describe Motown as if it were a timeless and impregnable virtue – but as 1967 unfolded it was a term that was shattered under the weight of over-use. He had grown up in a bustling post-war home, the second youngest child in a family of ten. He had been married three times, had four children, and racked up numerous love affairs. Those who knew of his past as a local boxer described him as at times pugnacious, a man who jabbed at problems, but when the fight hardened and the gloves came off, he often weaved away from direct confrontation. Despite his skill in the ring, Gordy spent most of 1967 trying to avoid fights and when Motown’s most talented stars reached a point where they wanted to know more about his business and its worth, Gordy often withdrew and took animosity like a punch-bag.

In the freezing early hours of the new year, Detroit had claimed its first victim. Kenneth Biel, a fourteen-year-old boy from Oak Park, lay dead in the snow, his face resting on a pillow of solid ice beneath a row of elm trees. When his body was first examined at the Wayne County morgue, his death was attributed to intentional carbon monoxide poisoning, but his parents reacted badly to the news and resisted any suggestion of suicide. A subsequent investigation determined that the teenager had been drinking cheap whisky and then slumped down drunk by a tree not far from his home. Still hunting for dignity in his death, the family denied that their son had ever drunk alcohol, but the police confirmed that buried beer bottles had been found nestled in the snow and patches of spilled liquor had burned into the rock-hard Michigan soil below. Biel was from Detroit’s Motown generation, a young white teenager discovering girls, music and cheap thrills, and growing up in a city witnessing change on a massive scale. But like most of the events that were to unfold in 1967, his death was shrouded in doubt and his funeral mired in dispute. His friends disagreed with his parents, who disagreed with the police, who in turn were not wholly convinced of their own version of events. It was a tragedy that proved to be prescient of the twelve months ahead – a year that was destined to become one of unexplained deaths and conflicting narratives, a time in which friendships would fracture into ugly and irreconcilable shapes. Even the morgue where Biel’s body was taken was destined to become an unlikely character in the year ahead, embroiled in cases of missing bodies as Detroit’s death toll mounted and the city’s budget came under unprecedented pressure.

The only good news was soul music. Detroit’s conveyor belt of black music had triggered a creative Klondike and small four-track recording studios were crammed into suburban homes and basement cellars. More than 400 independent music labels had sprung up in the city in less than five years. The vast majority of these local enterprises were undercapitalised and destined for obscurity, but it proved to be one of the most creative moments in the history of pop music, and for those who found success, it was the era that defined their lives. The sudden influx of cash into predominantly poor households overturned the natural order: rivalries were intense, egos went unchecked, and the city crackled with the energetic sound of black America. ‘The stream of hits was endless,’ Gordy said in his autobiography To Be Loved. ‘The whole world was fast becoming aware of our artists, our songs, our sound. I was being called a star-maker, the magic man.’ Gordy’s magic was in many respects predicated on a compromise. He had softened the rough edges of rhythm and blues, draped the music in the familiar cadences of teenage love, and his girl groups – borrowing from predecessors like the Ronettes and the Crystals – pioneered a highly addictive form of ‘bubblegum soul’ that lent itself perfectly to the still-segregated radio stations of America. Phil Spector, a major influence on the Motown Sound, described it as ‘little symphonies for the kids’. It was in every respect an art of repetition: familiar backing tracks were refashioned, everyday phrases repackaged and the anxieties of young love were played out as memorable drama.

Gordy’s sorcery was founded on talent and circumstance. Detroit had an enlightened public-school system that brought classical music, choral training and jazz into ghetto classrooms. The city had hundreds of churches dotted along its main boulevards, and the gospel choirs were among the most competitive in black America. More importantly, Detroit had a magnetic force that drew talent towards it. It had been a hub of inward migration for over 200 years dating back to the Underground Railroad network that helped fugitive slaves escape north to Detroit and then over the river to freedom in Canada. For decades it was the southern states that provided Detroit’s human capital. All three members of the Supremes could trace their family’s roots back to the Deep South; Eddie Kendricks and Paul Williams of the Temptations had been part of a more recent migration and came north from Birmingham, Alabama; Marvin Gaye had relocated from his native Washington DC, via jazz and doo-wop; and an eccentric barber named George Clinton had moved from New Jersey to join the local Revilot label and to lead yet another emergent group, the Parliaments. Most came prospecting for gold discs and found themselves in a city of unrestrained rivalry, vocal brilliance and bitter feuding.

Motown was based in a converted house at 2648 West Grand Boulevard on Detroit’s West Side. It was an unremarkable shambles of a place with only the most basic facilities. Situated on a street that had only recently been reclassified to allow commercial businesses, it sat among local homes and other hopeful businesses, including a doctor’s office, a funeral parlour, the Your Fair Lady Boutique and Wig Room, and Mr Sykes’s Hernia Clinic. The Motown neighbourhood near General Motors headquarters had once been prosperous, but the shingled walls, polite porches and wooden window frames had all decayed with the passage of time. Mary Wilson, in her book My Life as a Supreme, described it as ‘a small nondescript two-storey house that had been converted to a photography studio’. Stevie Wonder’s mother, Lula Hardaway, remembered an office that was ‘brimming with people and noise – the entire house was teeming, chaotic, always, as if in the middle of an air raid’. Smokey Robinson’s staccato description painted a picture of cramped efficiency: ‘Downstairs became headquarters. Kitchen became the control room. Garage became the studio. The living room was bookkeeping. The dining room [was] sales. Berry stuck a funky sign in the front window – “Hitsville USA” – and we were in business.’

America was changing, too slowly for some, but nonetheless this small row of unremarkable houses had become the fulcrum of the most dynamic music business in the world. Soul had made Gordy phenomenally rich. Although he dressed fashionably in slick suits, he was always one of the more understated members of the family. His sisters Anna and Gwen, who had preceded him as label owners in the local independent music scene, were among Detroit’s black demi-monde and stepped out at night in ermine and mink. Gordy’s second wife, Raynoma, described the sisters as being bigger than the music itself. ‘Show business was Gwen Gordy’s middle name . . . She was exquisite from head to toe, with an assortment of gorgeous black wigs and dyed shoes to match all her outfits. Her face was flawless, and her figure was so stunning that later she would become a fashion model.’ By contrast, Gordy’s suits were off the rack. He had a half-hearted moustache and close-cropped hair in a vaguely military style that had changed little since he had served in the Korean War. And while the big stars of Motown travelled with monogrammed luggage, Gordy’s bags usually carried the imprimatur of BOAC-Cunard, the airline that ran weekly flights from Detroit to Europe.

Diana Ross, the regal lead singer of the Supremes, once described Gordy as ‘a genius open to abundant possibilities’. ‘He never thought small,’ Ross claimed. ‘No matter how difficult the challenge, he could envision and hold on to the big picture, and he had little time or patience for anyone who wouldn’t go there with him.’ Ross first fell in love with him in 1965 as they travelled together from venue to venue, and she soon began to speak of him as both a father figure and a lover, ‘an incomparable visionary, a dynamite character’. Even in the face of hostile criticism, she remained devoted to Gordy. She reorganised his virtues as a leader while others denounced him as a control freak, womaniser and a reckless gambler.

Gordy was years ahead of his time. He was obsessed with sales charts and publishing data, and how music was perceived by the different ages and demographics across America. His curiosity was instinctive and it anticipated major changes yet to come in the recording industry. At times his passion for music tipped into an autistic-like control. He was able to identify faults in a recording within seconds, and he worried away at recording takes as if he were counting on an abacus. Although he was wealthy enough to own the most up-to-date sound systems in America, he preferred to listen to his songs the way real people did – on box record players, on transistor radios, and in cars. Gordy often went against the acoustic grain of his studio engineers and turned the volume down, reckoning that many people listened to music in the background, not at its highest volume. He would sometimes drive around the block to listen to a song on his car radio rather than at the studio desk and he preferred voices that were pleasing but distinctive: singers like Tammi Terrell, Levi Stubbs of the Four Tops, and the tempestuous David Ruffin of the Temptations. One of his favourite voices belonged to his eccentric and emotionally unpredictable brother-in-law Marvin Gaye, who had married Gordy’s sister, Anna, in 1963. But Gordy was also deeply judgemental and often consigned new songs to the scrap heap on the basis of the first few incriminating beats. Careers had been cut short in those few decisive opening bars, and so artists across Detroit had come to respect and resent him in equal measure.

In the previous few days Gordy had experienced extremes of weather – the dry heat of Miami and the brutal cold of Detroit. The Supremes were performing at the Casanova Room at the fashionable Deauville Hotel on Miami Beach and had been contracted to do two shows daily using a local pick-up band, the Les Rohde Orchestra. They sang ‘Baby Love’ in Santa hats and posed for photographs on the bench beneath the sweltering Christmas sun. The stick-thin lead singer, Diane Ross, had by now glamorised her name to Diana Ross. Her friend, the stockier Florence Ballard, had shortened her name to Flo, while the third Supreme, the coquettish and fashionable Mary Wilson, was content just to be Mary. They sang happy holiday songs, signed autographs, flirted with the cameras, blew kisses to high-rollers, and smiled at staff in the hotel lobby. Fans gave them the ‘stop’ sign wherever they went. It had become the trademark opening of their worldwide hit ‘Stop In The Name of Love’, a rush of adrenaline that the rock magazine Rolling Stone described as quixotic: ‘The sound mixes with your bloodstream and heartbeat even before you begin to listen to it.’ By 1967, the Supremes had sung the song so often and performed the actions so many times, onstage, at industry conventions, and for fans’ photographs, that it had become an everyday obligation they all in different ways had come to resent.

In reality, the Supremes’ outwardly cheery and enthusiastic personas had become a carefully controlled deceit. Their friendship was under severe strain, they had travelled extensively for three years without a break, and they were exhausted – to the point of breakdown – by damaging disputes over workload and hierarchy. Although Christmas had thrown superficial glitter across the surfaces of their lives, back in their Miami hotel rooms the girls brooded alone, often phoning home for advice and emotional support. It was an unholy and unpleasant mess, poisonous venom had bored into the heart of the group, and friendships that had been forged during excited teenage years were cracking.

Gordy had made a short round trip to Florida in the last days of December 1966, ostensibly to choreograph the Deauville residency and supervise network television coverage of the annual King Orange Jamboree Parade. But his real motive was to act as a peacemaker and try yet again to bring a semblance of harmony back to the group. He had spent the last six months calming disputes and had become anxious that the in-fighting and bitching were about to go public. Hostile journalists were hovering around looking for a story, and although Motown had always counselled the girls to behave in public that too brought pressure. Gordy was not naive about the dynamics within the Supremes and had frequently chastised his girlfriend, Diana, about her role in provoking disputes. He instructed the road crew to enforce corporation policy at all times, reminding the Supremes that Motown had a family image and the last thing he needed was bad press, tantrums or empty bottles of alcohol in hotel bedrooms. He told them things would improve and that within a few days they would be on a flight back to Metro Airport, and then they could take a short break, hand out gifts to their families back in Detroit, and bicker in the comfort of their own homes. For now they were to look happy, wave to the crowds, and blow kisses to the cameras.

By the Christmas of 1966, American television networks were at their competitive height, and sales of colour TV sets had taken off. Gordy had been an early convert to the promotional potential of television and was convinced that the networks were the next logical phase of Motown’s success. He had mapped out TV as a priority for the company in 1967 and instructed Motown staff in Detroit to make a strategic shift of focus from radio to television and from small-scale live shows to television spectaculars. Gordy’s aim was to make musical history by taking black music into the living rooms of white America, which until then had been culturally resistant to soul music. Network television was by now a priority over everything, including family, friends and even concert engagements. Throughout the year, the Supremes appeared on all the major network television shows – The Ed Sullivan Show, The Andy Williams Show and The Tonight Show starring Johnny Carson – but their vibrancy onscreen masked a bitter, self-destructive war behind the scenes, one that would erupt into public view as the year unfolded.

The most popular girl group in the world were being pushed to the point of exhaustion, and all of them were on prescription drugs, trying to shake off a catalogue of illnesses. On the first day of the year, as Detroit lay engulfed in snow, the Supremes led a parade of marching bands and carnival floats down Biscayne Boulevard under a humid afternoon sun. They recorded two promotional shows. One was an NBC telecast from the Orange Bowl, broadcast on the morning of 2 January and presented by Lorne Green, best known as Ben Cartwright, the quintessential father figure from the TV series Bonanza. Lorne joked with the girls and acted as if he was the caring father of a multiracial family. The second show was a pre-recording of the Ice Capades, a variety show on ice starring American ice-skating champion Donald Knight and life-size characters from the cartoon series The Flintstones. It was scheduled for broadcast in February.

On the third day of January, Gordy received a series of frantic phone calls from Miami. There had been a car accident and two of the Supremes had been rushed to hospital; there were fears that one or more of them were on life-support. Information was sketchy, and neither the police nor hospital staff could give a full account of what had actually happened. An officer with the Miami police had tried to reach Gordy but failed to get through, and so Motown were forced to respond to questions from local reporters without being in full possession of the facts. Eventually it emerged that a car crash involving three vehicles had taken place at the junction of Sixty-Fifth and Collins, just south of the Deauville Hotel, and that various passengers – including two of the Supremes, Diana Ross and Florence Ballard – had been rushed to the hospital. Police had already charged a Motown security guard named Barry Don Oberg with dangerous driving. By the time the patchy news reached Detroit, the girls were in separate rooms at Miami’s St Francis Hospital. Shows were hurriedly cancelled and audiences turned away disappointed. When the full picture began to emerge, however, it was significantly less dramatic than Gordy had been led to believe. The girls had been on their way to an afternoon fishing trip when the accident happened, and although they were kept in the hospital overnight, Ross and Ballard were released with only superficial wounds. Mary Wilson had stayed back at the hotel to relax by the pool – possibly an act of personal respite. She had become increasingly caught up in persistent disputes between Ross and Ballard, and rather than take sides often simply avoided their company.

Ross and Ballard cuddled and consoled each other on their way back to the hotel, and it momentarily appeared as if the trauma of the car crash had allowed peace to break out. Hearing it all second-hand, Gordy had a good feeling about the incident and told his sister Esther that it was a wake-up call that might just shake the girls out of their constant bickering. But it was wishful thinking. Back at the hotel, another argument erupted, and each of the Supremes returned to their separate rooms in rancorous silence. Divisions within Motown’s biggest-selling group were already deeper than the Detroit snow.

Deep snow drifts had stacked up alongside a stretch of old converted stores by the John Lodge Freeway. Inside the ramshackle buildings were the headquarters of the Detroit Artists Workshop, the Committee to End the War in Vietnam, and the offices of a group of political subversives who were known by the mysteriously bureaucratic name ‘the Steering Committee’. They had launched the year with a mission statement that threatened social unrest: ‘This is truly a new year. We have been preparing for 1967 all our lives, and we are ready for it now.’ Trapped by the snow, they passed their time playing jazz, planning disruption, and plotting the downfall of America. Over the next few years, they would become notorious across the city. There was John Sinclair, a jazz-obsessed journalist from Flint, Michigan, Gary Grimshaw, a graphic artist from Lincoln Park, Jim Semark, a poet and student at nearby Wayne State University, and Rob Tyner, a local singer whose real name was Robert ‘Bob’ Derminer but who had adopted the surname of jazz musician McCoy Tyner. Tyner was the lead singer of a then unknown Detroit guitar band, the Motor City Five, which by the end of 1967 were rechristened MC5 and destined to become the vanguard of Detroit’s other great musical subculture: insurrectionary garage rock.

The Steering Committee was plotting social change, borrowing promiscuously from cool jazz, the American beat poets, and Detroit’s black Muslim firebrand, Malcolm X. In one audacious manifesto, they threatened to disrupt Detroit with rock music, declaring ‘a total assault on the culture by any means necessary, including rock and roll, dope, and fucking in the streets’. They had fashioned numerous half-secret identities, sometimes working under the name Trans-Love Energies, sharing office space with LEMAR (LEgalize MARijuana), and hosted fundraisers for the anti-war movement. But unknown to the storefront radicals of the Steering Committee, they had already been infiltrated by undercover police officers working for the Detroit narcotics squad, and their lives were about to turn upside down. The Steering Committee was on a growing list of underground groups whom the FBI’s counterintelligence network had identified as a threat to American security, but within a matter of a few years, despite being monitored almost daily, they delivered on their bombastic promise. MC5 became a self-styled ‘guitar army’ and one of the most controversial rock cadres in the kaleidoscopic history of rock counterculture.

Detroit was divided by race and social class, and although the hives of creativity that grew up around Motown and MC5 developed only a few miles apart, the racial characteristics of the city meant that they occupied profoundly different worlds. Berry Gordy was the undisputed boss of Motown; if the Steering Committee had anything as conventional as a leader, then it was affable jazz freak John Sinclair, who wrote passionate diatribes for the jazz magazine Downbeat and had recently been released from DeHoCo, the Detroit House of Corrections, where he had served a short sentence for possessing marijuana.

The bearded Sinclair was a giant of a man. His writings were a hybrid of gonzo journalism, revolutionary rhetoric and jazz homage, and his musical tastes shifted eclectically from day to day, jumping restlessly from free-form jazz to gutbucket R&B and onward to the nascent noise of garage rock. Music and drugs fused in his mind, and he vowed in his prison writings to change America ‘by the magic eye of LSD and the pounding heartbeat of music’. Within a matter of a few months in early 1967, he became the mentor and then the manager of MC5, who were destined to become the demonic fathers of punk rock. The band’s name was deliberately vague, designed to sound like a car component. Although technically short for Motor City Five, the band sometimes claimed that MC5 stood for the Morally Corrupt Five or the Much Cock Five – whatever the band members made up in the presence of gullible journalists. Sinclair added to the hyperbole, describing the group as ‘a raggedy horde of holy barbarians, marching into the future’. It was not just posturing. Within two years they would be the most notorious band in America, and Sinclair would be back in jail, this time as an international cause célèbre accused of conspiring to blow up the Michigan headquarters of the CIA.

Sinclair despised Motown. He was suspicious of Gordy and the grip he had over young artists, and believed that Motown was peddling an anodyne, compromised and saccharine style of R&B that did not deserve the name soul and had fatally compromised a rougher and more honest form of black expression. Periodically, he used his Downbeat column to comment on Detroit’s local black music scene, and he did it with unrestrained passion, often by disparaging Gordy’s burgeoning empire. It was a one-way rivalry. Gordy never replied, and it is not even clear whether he knew he was under attack. Sinclair, like many others of his generation, felt that Motown had diluted the burning liquor of R&B and turned it into a soft drink. In one near libellous attack, he described Motown as an ‘exploitation creep scene’ and accused Gordy of ripping off naïve and impressionable young ghetto singers, or ‘spade groups’, as he routinely called them.

It was not the first time Gordy had been accused of exploitation. His own musicians whispered behind his back, and the term ‘exploitation’ was to pursue him – often unfairly – for the rest of his working life. Gordy was not a particularly litigious man, nor was he easily wounded. He tended to brush off criticism with a shrug. He had a work schedule stacked higher than the snow and precious little free time and was not about to waste time pursuing a bickering jazz critic or the half-chewed polemic of local hippies. Gordy treated the Steering Committee with the ultimate disdain: he didn’t appear to even know they existed.

Motown and the Steering Committee lived in different versions of Detroit, a city where housing was still largely segregated, where communities existed incommunicado, and where suspicion had crept into everyday life. Gordy and Sinclair were both hard-core jazz fans who bought records from the same makeshift shops, but they heard radically different things in music. Sinclair was the son of a teacher, and heard a revolutionary zeal in jazz and thought it angry, disruptive and challenging. Gordy had grown up under the stewardship of an immensely aspirational black family who had already escaped the ghetto. He had come to resent the way that African-American music was marginalised. Gordy was determined to occupy the mainstream; to him anyone who wanted music to change the world through disruption was speaking a different language.

A growing number of people in Detroit did want to change the world. The war in Vietnam was escalating, and by the evening of 2 January, Detroit had lost another victim, but this time the death was far from home. In Vietnam, dense wet fog and swollen rice paddies had bogged down US patrols around the Hoa Basin in South Vietnam, and in a brief flurry of confusion, eighteen-year-old George Scanlan of the Eleventh Military Transport Battalion, an Irish-Catholic boy with twelve siblings from the northeast side of Detroit, was shot in the stomach. It was less than a week since Scanlan had landed at Da Nang Harbor, and a close friend told the local press that his death was ‘a call to reality’. Scanlan was the first of several hundred young men from Detroit who would be killed or seriously injured in 1967. Unlike Scanlan, most were black and many had been recruited from the ranks of the city’s unemployed. Gordy had served in Korea and was predisposed to the military effort. He viewed everything through the prism of music sales and rarely talked about politics. The Steering Committee was less reticent. It was already at the vanguard of a restless Detroit underground that was willing to mobilise against American militarism and stop the war.

Although their paths never crossed, Berry Gordy and John Sinclair both owed a debt of gratitude to the irrepressible ‘Frantic’ Ernie Durham. Frantic Ernie rocked Detroit. He was a famous R&B DJ on WJLB and had a custom-built studio in the Gold Room of a local nightclub called the 20 Grand, a bowling alley, jazz lounge and soul venue which sat astride a corner on Fourteenth and Warren. Ernie was just one of the formidable cast of characters drawn there. A master self-promoter, he came after bebop but before hip-hop and spoke in rhyming couplets in the demonstrative language of cool: ‘Cut the chatter and roll a platter, it’s “Treasure Of Love”, by Clyde McPhatter.’

You had to hand it to Ernie Durham – he had never been restrained by shyness. He once sold pots and pans around the streets of Harlem, hustled a job as a news anchorman, and then moved to Detroit, where his frantic delivery style made him one the most popular DJs in the Midwest. Frantic Ernie was in such demand that he had two shows on the same night, one in the blue-collar town of Flint, where Sinclair grew up, and the other deep in the heart of the Motor City. He drove frantically from one show to the other, come rain or snow, with an entertainer’s contempt for speed limits, never missing a beat and never missing a show.

Gordy owed Durham. He hand-delivered the DJ newly pressed Motown records as soon as they saw light of day. Whether it was Stevie Wonder or Hattie Littles, the stars who shone brightest or those who simply disappeared, Ernie Durham played them all, and his influence was all pervasive. John Sinclair of the Steering Committee saw him as a sort of shaman and singled him out as an influence in his memoirs: ‘I just turned the radio dial one day, sitting in my little bedroom in Davison, Michigan, and boom! There it was – the music that would turn my whole life around and shoot all of us into a totally new future.’ Sinclair had grown up smitten with R&B, and the music had left an indelible mark on him. ‘It was incredible,’ he once wrote in Guitar Army, a series of collected essays, where he paid bombastic homage to artists like Little Richard, James Brown and Detroit’s Little Willie John: ‘These dudes opened their mouths to sing, and a whole new race of mutants leaped out dancing and screaming into the future, driving fast cars and drinking beer and bouncing around half naked in the backseats, getting to march through the sixties and soar into the seventies like nothing else that ever existed before.’

As a sixteen-year-old high-school student, Sinclair had become so besotted by the new R&B he cast himself as Durham’s acolyte. As a disc jockey at high-school hops in the Flint area, he even used the moniker ‘Frantic John’, playing records by Little Richard until the lights went out. By 1967 his schoolboy nickname was long gone, and the local press now dubbed him ‘the high priest of Detroit’s hippies’. As the winds of change circled round Detroit he remained loyal to the subversive power of R&B: ‘These black singers and magic music makers were the real “freedom fighters” of America, but nobody even knew it. They walked right into the bedrooms of middle-class Euro-Amerika and took over, whispering their super sensual maniac drivel into the ears and orifices of the daughters of Amerika, turning its sons into lust-crazed madmen and fools.’

By 1967 Frantic Ernie Durham’s power was in decline and the old R&B radio-station era he had come to personify was hanging on for dear life. The executive team at Motown believed that the R&B of their youth was trapped in a ghetto of its own making and was stuck in the past. They still kept the old-style DJs onside, but time was passing them by and the tastes and infrastructure of the city had changed around them. The freeways through Detroit had wiped away many of the ageing R&B haunts. Hastings Street, in the old Black Bottom ghetto on the near East Side where Gordy had grown up when his family migrated north from Georgia, had been bulldozed to make way for the Chrysler Freeway. New supper clubs were springing up, and network television was a direct route to bringing pop music into American homes. The radio personalities that had inspired Gordy as a teenager – Frantic Ernie Durham, Joltin’ Joe Howard, Long Lean Larry Dean and Martha Jean ‘the Queen’ Steinberg – were losing their grip on power. They had been transistor gods in the late fifties and had helped out when he’d hawked his first Tamla releases around town, but with each passing year the new FM stations and the growth of television eroded their relevance. Even Frantic Ernie was slowing down.

When Mary Wilson of the Supremes first met the Gordys, they had left the Hastings Street ghetto behind and become a ‘prominent middle-class Detroit family’. She witnessed Gordy’s success close-up. ‘There were lots of young entrepreneurs like Berry around in the fifties,’ she wrote. ‘In those days some of these men were looked on as hustlers, and to some degree, I guess they were. The music business was tough, unlike any other hustle. Smooth talk went only so far; sooner or later you had to deliver the goods.’ Gordy had absorbed a more resilient sense of business at the Booker T. Washington store, his father’s small neighbourhood grocery at Farnsworth and St Antoine. The store was named after the nineteenth-century Negro educator Booker T. Washington, whose philosophy of self-help had shaped three generations of ambitious African-Americans since slavery. Even in childhood, Gordy had been taught to challenge discrimination and seize success. His second wife, Raynoma Liles, described the early years of Motown as living in a tornado, and she felt swept along by unpredictable energy. In a score-settling book Berry, Me and Motown, she described Gordy as ‘a born leader’ with ‘an unquenchable gift for infusing a group with such spirit that they’d come out of a meeting fired up and raring to go’. But those who described his success as meteoric or unbridled were only telling part of the truth. Gordy’s first music venture, running a local jazz store, failed ignominiously. His fascination with jazz was not universally shared, and he naïvely invested in racks of obscure records that remained undiscovered and unsold. One periodic customer was John Sinclair but the shop was not open long enough for anything close to recognition. Pops Gordy, the family’s sage, frequently recited an enduring family motto: ‘A smart man profits from his mistakes.’ It was a lesson his second-youngest son learned the hard way. For a period of time in 1964, Motown itself teetered on the brink of bankruptcy, and there was widespread anxiety within the family that he was staring another catastrophic failure in the face. It was Gordy’s more financially savvy sister Loucye who rescued the business by implementing improved management systems and changing the terms of recoupment in order to improve liquidity and cash flow. She was of the view that raw talent was meaningless unless you could claw in revenues quickly from national distributors.

Despite these early setbacks, by January 1967 the great-grandson of a dirt-farm slave from Milledgeville, Georgia, had broken the mould of American music. He had taken the Supremes into the mainstream of America’s white pop market. When it came to understanding and exploiting the music market, Gordy had few rivals. He was an instinctive entrepreneur who had absorbed business acumen around the kitchen table or behind the counter at the grocery store. He knew that the music business was different, but he was wise enough to know it wasn’t that different, and that what he didn’t know could be learned from his sisters or his father. Pops Gordy was a wire-thin man with a pointed grey beard that seemed to accentuate his long skinny face. A product of the Great Migration north, on his arrival in Detroit in the twenties he had been the unwitting victim of a property scam. He’d lost the family’s life savings when he tried to secure a lease on a dilapidated slum from a rogue landlord. It was a humiliating setback that dented his self-esteem and left the family in dire straits, but wounded pride was to breed an even greater desire to succeed and a lifelong hatred of low-level cheats and criminals. Within a matter of another ten years, Gordy Sr owned several small businesses: a plastering company, a printing shop, and the jewel in the crown, the Booker T. Washington grocery store.

Hard work, social enterprise and lifelong learning were to become a Gordy family trait and the underlying reason that Motown ultimately succeeded. While raising her seven children, Gordy’s mother, Bertha, had carved out her own career. She was an agent for Western Mutual Insurance, studied retail management at Wayne State University, and ran several local initiatives. She eventually set up one of Detroit’s first mutual insurance companies aimed at low-income black families and was an activist in the Detroit chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). For a period of time in the early sixties, she was a branch member of the Housewives League of Detroit, a group led by the visionary community activist Fannie B. Peck. It was a social enterprise that sought to convince black housewives that they could influence the economy by targeting their household spending at stores owned by African-Americans. Under the galvanising motto ‘Stabilize the economic status of the Negro through directed spending’, the Housewives League turned their purses into a political force. This spirit of self-help became the Gordy family’s core value, and it was in the new year of 1959 that Berry Gordy applied for a business loan to set up the Motown Record Corporation.

While many aspiring black businesses were locked out of start-up funding by discriminatory banks or by restrictive commercial contracts, Gordy had the option of applying to his family’s own bank, the Ber-Berry Co-op, a family fund established by his mother. The headquarters of the Gordys’ mutual fund was around the family dinner table at 5139 St Antoine. It was a tense meeting at which his usually loyal sister Esther voiced significant doubts about the music distribution industry and its inherent racial bias. Despite her interventions Gordy was loaned $800 to launch Motown. It proved to be one of the most spectacularly successful start-up investments in the corporate history of America. Gordy’s sisters already ran a network of small businesses across the city, from cigarette franchises to record labels. Preeminent among them was the cautious Esther, who founded the Gordy Printing Company, and Loucye, who became the first black administrator at the Michigan Army Reserve at Fort Wayne. Both were eventually recruited to Motown in senior positions, and although they were among Gordy’s most trusted allies, there was an underlying sense that they had been put there to protect the family’s investment. When the company faced any major problems, it was to his sisters that Gordy instinctively turned.

Snow fell persistently throughout January. For those raised in Detroit, extremes of weather triggered personal memories of childhood long into adult life. For Motown’s first solo star, Mary Wells, snow signified the crushing poverty of her early years. She was the daughter of a single mother and an absentee father, and worked punishing hours through a series of childhood illnesses cleaning apartment corridors in the fierce cold of winter. ‘Day work, they called it, and it was damn cold on hallway linoleum,’ she said many years later. ‘Misery is Detroit linoleum in January with a half-froze bucket of Spic and Span.’ For Florence Ballard of the Supremes, snow also provoked memories of a hand-to-mouth upbringing in ghetto neighbourhoods across the city. ‘I remember singing,’ she once said. ‘My favourite song was “Silent Night”. It seemed like every winter I was pulling up the window and singing that.’ The more privileged Aretha Franklin, who was the daughter of the charismatic preacher C. L. Franklin and had grown up in a mansion not far from Motown, remembered snow creating a carpet of poetic ‘beauty’ with giant flakes ‘falling softly across the city’, so deep that ‘life just stopped’. For the original members of the Temptations, it meant cold keys on a battered piano as they sat huddled in woollen winter coats in the basement of Hitsville as the snow fell relentlessly outside.

For Berry Gordy, snow was a reminder of the day he nearly died. He was driving through a blizzard in 1959 with his best friend Smokey Robinson. They were on their way to the American Record Pressing plant in Owosso, Michigan, at the height of one of the area’s worst-ever winter storms. Ten inches of snow fell in a single day. Although logic said they should turn back, Gordy and Robinson continued to drive towards musical history. They were on their way to pick up a batch of newly pressed copies of Marv Johnson’s ‘Come To Me’, the debut release on their cherished Tamla label and one of the first releases of the Motown empire. Driven on by reckless enthusiasm and desperate to lay their hands on the first box of newly minted records, they battled through the snow. The plan was to return to Detroit that night and distribute promotional copies to radio DJs across the city. Then Gordy’s ’57 Pontiac skidded off the state highway and into a field. An emergency tow truck was summoned to drag them from a snowbound ditch. Battered and bruised, the men were pulled out of the wreckage and escorted home in the tow truck through the snow-packed suburbs of Detroit. They survived, but Motown itself was nearly stillborn.

Gordy made several calls to Florida and spoke at length to Diana Ross. She was recuperating from the road accident and spending her time by the pool at the Deauville Hotel. The Supremes had been slow starters, and Gordy had seriously considered scrapping their contracts back in 1963. Four years before, they couldn’t deliver a hit song for love nor money, but when success did come, it was sudden and transformational. By January 1967 the Supremes were bigger than any act that had ever emerged from Detroit – bigger than Jackie Wilson, bigger than Mitch Ryder and the Detroit Wheels, and significantly more profitable than Motown’s leading male groups, the Four Tops and the Temptations. Their effervescent black-girl-next-door style had struck a chord in a society where attitudes towards race and segregation were evolving. But Gordy had sensed that the Supremes could go further still and that their journey to the mainstream, breaking down the invisible barriers to acceptance, was not yet complete. One-hit wonders would come and go, but a group that could achieve global success was something he strove for.

Working with his sister Esther, Gordy had mapped out a punishing schedule designed to maximise every opportunity that came the way of the Supremes. It was a gruelling plan, at times verging on sadistic, but everyone had signed up for it, knowing that global success was well within their reach. 1967 marked their third successive year of travelling during which all three of the Supremes had faced periods of exhaustion, illness and mental breakdown. The relatively relaxed residency in Miami only disguised the relentlessness of their normal workload – the public engagements, twice-nightly concerts and red-eye flight itineraries. Insiders worried that one of the Supremes might collapse onstage or be hospitalised with fatigue. It had happened before. Between 1965 and 1967, all three members of the Supremes had spent time in hospital. Gordy had been generous with gifts but showed no inclination to reduce their workloads. Nor was he willing to compromise on quality control. The Supremes were frequently sent back to the studios together or individually to re-record songs or improve on tracks; those that fell short, like the song ‘Deep Inside’, were simply shelved as sub-standard. Gordy knew that pop music was quixotic and to take time out or entertain a more reasonable schedule risked their place in pop history. By January of 1967, the strain on the Supremes had reached breaking point. They had begun to hate the sight of each other.

Gordy had wrestled with internal dissent before and had managed disputes within other Motown acts, but what was different about the three Supremes was that their disputes had become increasingly bitter and threatened to drive them apart. There had been several incidents on the road, mostly in private or backstage, but well known to Motown staff. On a couple of occasions, disputes between Diana Ross and Florence Ballard had spilled over onto the stage. It was not always clear what really lay behind the dispute. Jealousy, petty hierarchies and misunderstandings were part of it, but familiarity had also begun to breed a corrosive contempt. Simply being together day in and day out was the root of the problem. The mood backstage could change on the weakest of jokes or a perceived slight. None of this reflected well on Motown, which, for all its sophistication in artist management, was still viewed by many in the industry as an outsider, a black-owned company on the outer edges of American society.

Like many people facing an apparently insurmountable problem, Gordy chose to ignore it in the vain hope it would go away. But after months of agonising, he had come to the conclusion that the fights would never end. Ballard was a founding member of the Supremes and had been the lead singer and de facto leader of the group when they were known by a previous name, the Primettes, but she seemed increasingly isolated and detached. Her light reddish hair had given her the teenage nickname ‘Blondie’, and Motown mythology claimed that it was Ballard who had originally come up with the Supremes’ name. Her attitude towards Gordy had once been flirtatious and even devoted, but by 1967 it had changed completely. She had become sullen and resentful, portraying Gordy as an uncaring boss and his girlfriend, Diana, as a self-centred and scheming manipulator. The demands of fame, extensive travel and Gordy’s intimacy with Ross had exacerbated the bad feeling and turned the once loyal Ballard into someone who seemed ungrateful and insubordinate. Initially Gordy had dismissed Ballard’s attitude as a passing storm and waved the problem away when others mentioned it, but time was not a healer, and her feisty insolence refused to recede. Gordy had realised that ignoring the disputes at the heart of the Supremes would risk Motown’s greatest opportunity. Over a few soul-searching months, towards the end of 1966, he had made the decision to stand up to Ballard’s outbursts or what he increasingly described as her ‘crazy behaviour’. He had been discreet about his views and only really discussed his plans in any detail with his sister Esther.

By 1967 Motown was a fully-fledged international corporation with targets, a sales force, and a well-oiled distribution chain. Reaching the top of Billboard