Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Allen & Unwin

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

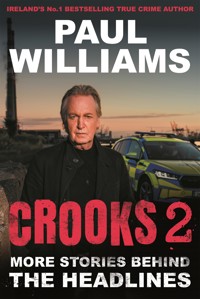

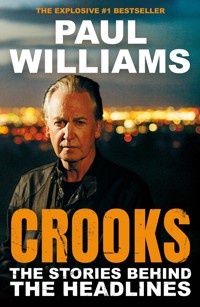

THE #1 IRISH TIMES BESTSELLER For almost forty years, Paul Williams has chronicled the life and crimes of some of Ireland's most notorious godfathers, killers and thieves. In Crooks he brings his readers for a ride-along, taking us behind the scenes of his most notorious scoops, describing the run-ins he's had with unsavoury, dangerous criminals and the high price of his line of work. From pursuing the General to death threats from PJ 'The Psycho' Judge, exposing the Westies and tracking the Kinahan cartel, Paul's extraordinary career doubles as an eyewitness account of the evolution of organized crime in Ireland.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 559

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

ALSO BY PAUL WILLIAMS

Gilligan

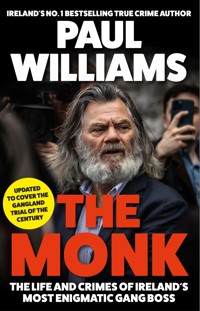

The Monk

Almost the Perfect Murder

Murder Inc.

Badfellas

Crime Wars

The Untouchables

Crimelords

Evil Empire

Gangland

Secret Love (ghostwriter)

The General

First published in Great Britain in 2024 by Allen & Unwin, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

This paperback edition published in 2025 by Allen & Unwin.

Copyright © 2024 by Paul Williams

The moral right of Paul Williams to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

Photographs (c) the author, Irish Independent, Sunday World, Charlie Collins and An Garda Siochana.

Every effort has been made to trace or contact all copyright-holders. The publishers will be pleased to make good any omissions or rectify any mistakes brought to their attention at the earliest opportunity.

No part of this book may be used in any manner in the learning, training or development of generative artificial intelligence technologies (including but not limited to machine learning models and large language models (LLMs)), whether by data scraping, data mining or use in any way to create or form a part of data sets or in any other way.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

E-book ISBN 978 1 80546 120 3

Allen & Unwin

An imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London WC1N 3JZ

Dedicated to my family, friends and colleagues who provided love, support and encouragement. And to the many unnamed gardai whose interventions saved my life and protected my loved ones on more than a few occasions.

CONTENTS

Prologue

CHAPTER ONE:

Crime Reporting

CHAPTER TWO:

Unmasking the General

CHAPTER THREE:

Publish and Be Damned

CHAPTER FOUR:

Shootouts and Death on the Streets

CHAPTER FIVE:

The Psycho

CHAPTER SIX:

The Battle for Gallanstown

CHAPTER SEVEN:

The Plague, The Godfather and The Junkie

CHAPTER EIGHT:

Exposing the Westies

CHAPTER NINE:

Finding Larry Murphy

CHAPTER TEN:

The FBI: A Hero, 9/11 & The Hunt for Whitey Bulger

CHAPTER ELEVEN:

The Era of the Narcos

CHAPTER TWELVE:

Living Dangerously

CHAPTER THIRTEEN:

Danger Looms

CHAPTER FOURTEEN:

The Bomb Scare

CHAPTER FIFTEEN:

The Cost of Fear

Epilogue

PROLOGUE

The memory of covering my first crime story forty years ago has not faded with time.

It was a cold afternoon on a bleak windswept mountainside in Leitrim in mid-December 1984. I was standing frozen to the spot, arms in the air, staring down the two long, shiny barrels of the old shotgun pointing straight at me from a few feet away.

My startled gaze met the owner’s razor-sharp eyes as they peered unblinking between the two silver hammers at the operational end of the ancient weapon.

‘I shot Black and Tans with this and I’ll do the same to you, ya tinker.’

The hard edge to the pensioner’s voice left no doubt that he and his trusted gun had indeed dispatched a few of the hated British paramilitaries over sixty years earlier.

The situation wasn’t helped by the fact that the stranger who’d called to his door was a dishevelled looking nineteen-year-old in faded jeans and an old combat jacket. I had no doubt that he could do it again. The veteran of the War of Independence assured me the weapon was loaded. I believed every syllable he uttered as he sat in a chair facing the door in the modest, white-washed cottage on Sliabh an Iarainn – the mountain of iron – in whose shadow I had grown up.

Fresh out of college and full of enthusiasm I was four months into my first staff job as a cub reporter with my local newspaper, the Leitrim Observer. I had come looking for a scoop, not expecting the prospect of getting a belly full of buckshot instead. In those unforgettable few moments of pure fear it looked like my career was about to end before it even got started. It was a baptism of fire in a job where threats of being shot would become an occupational hazard in the years ahead.

The antique shotgun and its owner John Bernard Keaney, the eighty-two-year-old warrior, were the reason I was there in the first place. My initial foray into crime reporting involved chronicling a terrifying phenomenon which suddenly emerged in the winter of 1984 and has haunted rural Ireland ever since. Four decades later it has effectively become normalized and is euphemistically categorized as ‘rural crime’.

It involved gangs, mostly from the Travelling community, who began specializing in targeting the most vulnerable people in society – elderly folk living in isolated areas in the north-west of rural Ireland. The counties worst hit were Leitrim, Roscommon, Sligo and Mayo. At the time the sudden upsurge in rural crime shocked the entire nation. Pensioners living alone were being robbed and beaten in their homes. I didn’t know it at the time but I was witnessing a watershed moment in our social history which shattered Ireland’s pastoral tranquillity and left people living in fear. A career in journalism is a constant learning curve and this was my stark introduction to a dark side of life I knew nothing about.

In November and December 1984 the number of raids had reached epidemic proportions. Over a number of weeks the owner of the Leitrim Observer, Greg Dunne, and legendary photographer Willie Donnellan took turns driving me the length and breadth of the county to interview the growing number of victims. I found it truly shocking. I grew up in a close-knit, peaceful, law-abiding rural community where keys were left in the door and our elderly citizens were treated with the utmost respect. Crime was practically non-existent in lovely Leitrim.

It was deeply upsetting to see and hear the fear in the faces and voices of people like my beloved granny Ellie who had passed six years earlier. I will never forget the sense of despair in the people whose trust in the world had been shattered in their twilight years. The old folks who had lived through the worst and poorest of times didn’t trust banks and believed in keeping their savings under the mattress. The money was for the ‘rainy day’ and to ensure there was enough for a funeral so that they would not be a burden on anyone. Our proud older generation wanted dignity in death. For that they were robbed and, in some cases, beaten and terrorized. It left me with a lifelong detestation of so-called ‘Travelling gangs’.

But there was one good news story on the back of the crime surge which was why I was trembling in front of John Bernard’s shotgun. I had heard on the bush telegraph that two weeks earlier he had sent a gang of thieves running for their lives in much the same fashion as I was now experiencing. I wanted to tell his heroic story.

He had plenty of reason to be on high alert. The week before my visit the crime spree had claimed its first murder victim when an eighty-two-year-old woman was beaten to death in her home in neighbouring County Roscommon. Brigid Cummins was fatally attacked with a broken chair when she and her elderly sister Mary confronted a burglar who had entered their bedroom in the middle of the night.

When I knocked on the door of the isolated cottage it was answered by John Bernard’s charming seventy-one-year-old wife Bridget. I remember her smile as I asked to speak to her husband. She said something like ‘he is here’ before calmly standing to one side to reveal the same double-barrelled shotgun I came to talk about. I instinctively hoisted my arms in surrender realizing that I could not move either forward or backwards without being caught in the blast.

I excitedly explained that I was from a few miles down the road in Ballinamore ‘and there’s no tinkers there’. I also told him I was with the Observer although I looked nothing like a reporter. I could hear Willie Donnellan’s car starting up as if he was about to leave. I have slagged my old friend about that ever since. I told John Bernard that Willie was – I hoped – with me. Willie has always been a household name in Leitrim.

After a few tense moments the mood suddenly changed and John Bernard and his wife broke into smiles. The reliable old gun was placed to one side and I was invited to ‘pull up close to the fire, son’ as they told their story over cups of piping hot tea. The thieves’ modus operandi was to arrive pretending to sell blankets and other goods. Then they either stole the money surreptitiously or terrorized their victims to hand it over. The gardaí later confirmed to me that the men who called to the Keaney’s isolated home were suspected of carrying out dozens of similar burglaries over the previous months.

They had arrived after dark. Two men approached the front door while the third remained in the car with the engine running. They were offering to sell blankets and were attempting to move into the house when John went on the defensive.

‘I got suspicious because it was the first time anyone came to sell blankets to me on a Sunday night,’ he recalled. It was then he introduced them to his reliable old war companion. Facing the double-barrel shotgun, the thugs vanished in seconds.

‘We weren’t afraid of the “Tans” and we’ll surely not be afraid of a bunch of boyos,’ said the former guerrilla soldier.

When I asked if he would have used the lethal weapon the veteran didn’t hesitate. ‘I haven’t got the gun for fun,’ he smiled.

John and Bridget posed for pictures after the tea, with him brandishing the fearsome weapon of war.

I was so proud as I watched the front-page story trundle off the ancient printing press on 15 December 1984. I felt that it would do some good, which is what it’s about for all journalists.

In the story the local garda superintendent warned of the result if people were prepared to protect themselves with guns. In a message clearly intended for the bad guys he told me: ‘At present we have an explosive situation if someone is forced to use a gun. It could have tragic consequences.’

In the days before the politically correct era of bullshit we now live in, the superintendent had no intention of depriving John Bernard Keaney of his shotgun. He wanted to inform the ruthless thugs – labelled ‘granny bashers’ by the rest of the Travelling community – of what might happen if they kept up their activities. Today, if a farmer or elderly person uses a gun to protect themselves it is automatically confiscated by the police.

Forty years later I am still highlighting the problem of rural crime. The more things change the more they stay the same. I have written many stories about innocent, decent people like John Bernard Keaney who have been murdered or left seriously injured when predatory monsters entered their homes.

Whenever I hear of another brutal crime committed against vulnerable rural dwellers I always get damned angry – and think of a gutsy old veteran who fought for a free Ireland and stood up for himself.

That experience on the side of the mountain coloured my view of the world. It launched my career writing about crime, criminals and their despicable acts.

CHAPTER ONE

CRIME REPORTING

It has been said that if journalism is the first rough draft of history then crime journalism has a habit of being rougher than most. I have spent the past forty years chronicling the roughest draft of history in the making – the evolution of organized crime in Ireland. From the front seat of what was often a white knuckle ride I have witnessed firsthand a lot of the seminal events which changed the face of the gangland that first absorbed me as a junior reporter. When I moved from the much more tranquil world of provincial journalism to the big city I realized that rural crime was only a small part of the complex picture.

My journey in crime reporting began while I was studying for the Leaving Cert. As an idealistic youngster looking for adventure I wanted to become a war correspondent. In 1983 I was accepted onto a two-year course in the School of Journalism at the College of Commerce in Rathmines, then part of the Dublin Institute of Technology, now known as Technical University of Dublin. It was the only journalism course in the country at the time and each year twenty-five candidates were selected out of about 300 applicants. To qualify for a place students had to get at least two honours in their Leaving Cert subjects, including English, and be successful at an interview in front of a three-person panel, consisting of the course supervisor David Rice, the then editor of the Irish Times Douglas Gageby and, appropriately enough for the profession concerned, a psychologist. When compared to other occupations journalism tends to attract a disproportionate number of eccentric people.

The panel picked the applicants who they reckoned were suited to the job of a hack. What many journalists of a certain age refer to as ‘Rathmines’ was the bedrock of Irish journalism. Amongst its alumni are several of the top names in Irish broadcasting and print media, international bestselling authors and several well known newspaper editors. My class included long-time friends John Burns and Stephen Rae. As deputy editor of the Sunday Times Burns made it one of Ireland’s biggest selling papers, and Stephen became the editor-in-chief of the entire Independent News and Media (INM) group. Another classmate was Orla Guerin, the BBC’s intrepid and much respected international correspondent. Then there was me, the guy who wanted to go to war.

I didn’t think that I had much of a chance of getting a place, especially when I had to explain why I had three secondary schools on my CV – as a rebellious kid I was expelled from two and finally settled down in the third, Carrigallen Vocational School, which, my long suffering parents reminded me, was my last chance of a formal education. The principal was Mick Duignan, an old family friend who decided to take a risk. Having to cycle ten miles a day to get there certainly focused me on my studies. I told the panel the unvarnished truth. One of the principles I always stuck by in my life and career is to tell the truth whatever the consequences. As a journalist the people you deal with must have trust in you. I said that my parents were both relieved and surprised that I had actually managed to do my Leaving and had then come out with good results.

Then there was my explanation to the panel as to how I came by the still bandaged nasty head wound. I had sustained it a few weeks earlier when I stole my mother’s new car and went for a joyride one night with a group of friends. My reckless escapade came to an abrupt end when I wrote it off after ploughing into a telegraph pole. We had a miraculous escape from what criminologists would describe as my primary act of law-breaking deviance.

To cap it all off when the interviewers asked me what kind of journalism I fancied I remember the look on their faces when I said war correspondent: This kid is mad.

My dad Benny drove me up to Dublin in the dusty pick-up truck he used in the family business which was quarry drilling. We looked a right pair of local yokels from the bog. Thanks to me the pick-up had become our primary mode of transport. Dad asked how I did. I said I had done shite and as we drove back to Leitrim we discussed what I was going to do next. I had already decided on a strategy in the likely event that I was rejected – I was determined to get a start in journalism. I had compiled a list of the names and telephone numbers of every provincial newspaper editor in the country. I planned to start at the top and work my way down. I was certain one of them would have a job for an enthusiastic rookie. Provincial newspapers have always provided the best training ground for journalists, before they can look to joining the nationals.

The telegram informing me that I had been successful was one of the most momentous experiences and biggest surprises of my life – there were no texts or emails in those archaic times.

After my first year I spent the summer on work experience at the Longford News but before I was due to go back to college I was offered a job on my local newspaper, the Leitrim Observer, by the owner Greg Dunne. The Observer had been the starting ground for David Walsh of the Sunday Times, the journalist who exposed Lance Armstrong as a doping cheat. I dropped out of my second year and my graduation. The summer months had convinced me that I could learn more on the actual job than in a classroom. In those days of high unemployment even David Rice advised that I should take the job when it presented itself.

I found myself in the strange position of reporting the news from my home town of Ballinamore. The Observer was one of the oldest papers in the country and one of the last still using the hot metal system. I loved the smells of the molten lead and the printing ink and the sound of the big very old printing press. I was witnessing a piece of publishing history which would shortly give way to new technology.

Rural crime was my first big story. However, I left the Leitrim Observer six months later when Derek Cobbe, the colourful owner of the Longford News, offered me a staff position. It was no reflection on the Observer – the News, based in a big town, was more exciting. It was one of the only full-colour newspapers in Ireland at the time. Derek Cobbe was an amazing, inspiring boss. A magician, hypnotist and artist, he was – and still is – a legendary figure in Irish newspaper history. His extraordinary flair for presentation and layout made him a pioneer. His deputy was another journalistic titan, John Donlon, a Rathmines alumnus, whose writing first attracted me to the paper. Four decades later he lives close by and still reminds me, ‘I taught you everything you know gosson, not everything I know’. In 1988 Donlon was appointed the first news editor of the Irish Star newspaper which was based close to the Sunday World, so he could keep an eye on me. Sixteen years later he became my news editor in the Sunday World where the sports editor, the late and much loved Pat Quigley, acknowledged his role in my career with the nickname ‘Bram’, as in Bram Stoker who also created a monster!

Donlon had previously trained another journalist – my future partner in life, Anne Sweeney – who was also from Ballinamore and a few years ahead of me in the business. She went on to earn numerous awards for her work and later worked for a time with the Irish Press. We met when she joined the Longford News. The paper was also the training ground of a number of renowned journalists who had departed for the bright lights of Dublin – Alan O’Keefe and Liam Collins. I always wanted to follow in their footsteps.

I had two wonderful years in the Longford News. We had a great editorial team, Donlon, Anne, me, the late Joe Donlon and photographer Willie Farrell, under the leadership of Derek Cobbe. The weekly routine included covering the local district courts and meetings of the county council, the urban council, the VEC, the agriculture committee and even local parish committees. Ciaran Mullooly was a junior reporter in the Longford Leader at the time, and would help me navigate the bewildering maze of EU-imposed agricultural acronyms. In 2024 Ciaran, who spent thirty years as an RTÉ correspondent, was elected as an independent Irish MEP.

In those years if there was a meeting the junior hack was dispatched to cover it. A lot of them were boring and it challenged our reporting skills to eke out the newsworthy angles and produce readable copy for the public. In summer there were agricultural shows, ploughing matches and festivals. I liked the festivals the best. I also did plenty of human interest stories about ordinary people’s lives. My first campaign, apart from covering rural crime in the Leitrim Observer, was highlighting the appalling living conditions of Travellers on the halting site at the edge of Longford town.

In 1986 I answered an advert looking for two junior reporters with the Sunday World. I jumped at the chance of joining the country’s most exciting tabloid. In many ways the broadsheet Longford News was as close to a tabloid as a provincial newspaper could get. I was told that a few hundred aspirant hacks had applied but in the end, much to my surprise, I got one of the jobs. I joined the paper in February 1987 with Cathy Kelly, a dear friend, who went on to become an international bestselling author. Under the guidance of our news editor, Sean Boyne, it was where I started the reporting on crime which has dominated my life ever since.

One of the unique features of working as a reporter is that you witness all human life in its most unvarnished form. It is a constant learning curve. Unlike any other area of the media crime reporters get close up and personal with the dark side of human nature. At the rough edge of history we see humanity at its rawest and most evil, reporting on violence, murder, tragedy, atrocity, greed and betrayal. Through the decades I investigated and exposed a fascinating and fearsome cast of characters – killers, paedophiles, rapists, armed robbers, drug traffickers, money launderers, fraudsters, extortionists and terrorists. To get around legal hurdles I started the tradition of giving them exotic sobriquets which contained a strong hint to their actual identities. In the process I made the criminals household names much to their often extreme annoyance.

I spent much of that time recording dramatic changes and seminal events as the underworld morphed from a motley collection of armed robbery gangs into a vast, multi-billion euro drug trafficking industry. Irish Crime Inc. is now a thriving international entity, with Irish narcos now dealing directly with the leaders of the most notorious cartels in the world, including those in Colombia and Mexico. When I joined the Sunday World in 1987 armed robbery was the stock and trade of organized crime. Within a decade it was exclusively narcotics, particularly cocaine, the Devil’s Dandruff, which continues to be the fastest growing commodity on the market – either illicit or otherwise.

In the process I observed the old gangland ethics of the so-called ‘ordinary decent criminal’ being swept aside by a much more violent and treacherous breed of gangster for whom life was as cheap as a bag of cocaine. With so much money at stake, greed, treachery and betrayal replaced the concept of honour amongst thieves. All gangsters by their nature tend to be social Darwinists who believe that only the fittest, strongest and most ruthless get to survive and prosper.

When I started out there were three main Irish criminal gangs led by the General, the Monk and ‘Factory John’ Gilligan. Today there are at least thirty large narco groups at the apex of a hierarchy consisting of scores of smaller outfits in a sophisticated and well organized international distribution network. At the top of the pyramid are the cartels run by Irish ex-pats Christy Kinahan and his sons, and George Mitchell, the Penguin. In the process the narco virus has seeped out beyond the cities and poisoned the countryside. Drug dealers now sell their wares in every village and town across Ireland. Crime has become part of the fabric of society.

I discovered early on that the lynchpin of organized crime is the symbiotic relationship that exists between civil society and the underworld. The dangerous latter could not prosper without the ambivalent former. Law-abiding citizens’ insatiable love of cocaine has generated an alternative economy and a new criminal subculture that has brought carnage and savagery in its wake. The drug dealer’s customers, who comprise a large cohort from all walks of life, are cognitively detached from their inadvertent role in the rise of the godfathers and the violence that they abhor and fear. The problem has created another disturbing social phenomenon whereby the families of drug takers are intimidated into paying their children’s debts.

The transition to the era of the narcos can be quantified in blood and misery. It created the new phenomenon of the gang war as the gun became the corporate tool of choice for the entrepreneurs vying for a share of the spoils.

In 1987 I covered my first gangland murder, that of a scrap dealer called Mel Cox who crossed swords with the family of Gerry Hutch, the Monk, whose life and crimes I have chronicled in articles and books. The criminal mastermind’s rise to gangland infamy coincided with the start of my career in national journalism. He and his gang pulled the biggest armed robbery in the history of the State a few days before I was given a desk in the Sunday World. They hit a cash-in-transit security van and made off with the equivalent of €3.3 million today. From that point on I developed an enduring interest in the enigmatic godfather and his crimes.

Of the cast of characters I encountered through my journey covering crime, Gerry Hutch stands out as being the nearest thing to being honourable and decent you can get in the underworld. It doesn’t mean he is clean as he has been connected to three gangland murders spanning forty years. Then there are the victims, mostly security staff, who were terrorized at gunpoint in the various heists. But I like to describe him as the least worst of them all.

The Cox murder, which had nothing to do with drugs, was the only gangland killing recorded in 1987. At the time I had no contacts to speak of as I was only finding my feet in a new world of cops and robbers. But from then on I gradually got to know gardai on the frontline, the people who knew better than anyone else what was actually going on. I met them in the courts and at conferences. In 1990 I was granted exclusive access to spend a fascinating day with the gardaí based at Store Street Station. I rode along in their squad cars as they raced between reports of robberies and assaults in and around O’Connell Street. When darkness fell I was in the local garda van as it was pelted with stones and bricks from the now demolished Sheriff Street flats. Some of the most remarkable and decent people I have met are members of An Garda Síochána. It helped get me hooked.

I also got to know criminals at the various levels of the gangland hierarchy. As I got better known on the crime beat, sources would make contact with information. People came forward for myriad reasons, from jilted lovers to gang members bearing grievances against their fellow mobsters. People would also come forward after reading a particular story to reveal other details.

In journalism protecting sources is sacrosanct. In crime journalism the responsibility is the difference between life and death. One of the criminals in this book, P. J. Judge, the Psycho, once plotted to have me kidnapped and tortured in order to identify who amongst his mob had been giving me inside information. Sources involved with gangsters put their lives and the security of their families at risk by telling what they know. The new murderous era of gangland has made it more hazardous than ever.

A decade after the Cox murder there was an average of twenty murders per year. By then I was immersed in the world of crime. Over that period I noticed a predictable pattern emerge in the life cycles of the average hoodlum. Ambitious low-level gang members who shoot their way to the top of the pile and become major players don’t often retire at the top or die in their sleep. If they don’t get busted by the police and sent to jail, they stay at the top for five or six years before falling foul of an even more violent and ambitious pretender to the throne. It is a paradigm for the dynamics of succession in a world where the only rule is that of survival.

The primal instincts of treachery and betrayal tend to be the root of most gang wars. Those same instincts sparked two of the worst gangland conflagrations I witnessed in all my years as a crime reporter.

The most recent was the mismatched Kinahan/Hutch feud in Dublin which claimed a total of eighteen lives, including two innocent bystanders. The vast majority of the killings, sixteen, were the work of the Kinahan cartel and their allies, in their attempt to wipe out the Hutch clan. It began in 2014 when Gary Hutch, the Monk’s nephew, double-crossed his boss Daniel Kinahan by trying to have him whacked. When the assassination attempt failed a peace deal was hammered out between the cartel and Gerry Hutch so that his nephew’s life was spared.

A year later Daniel Kinahan reneged on the agreement when he had Gary Hutch shot dead in Spain. The same day his sicarios went to kill Gary’s gangster father, Patsy Hutch, but failed. Then Kinahan stepped over the line when he sent his hit men to execute the Monk. Cops and crime reporters knew that a seismic eruption of violence was inevitable. When it came, however, everyone was stunned by the ferocity of the unprecedented attack on the Kinahan cartel at the Regency Hotel, north Dublin, in February 2016. It included a five-man hit team, three of whom were dressed as Emergency Response Unit (ERU) cops brandishing AK-47 military assault rifles.

The equivalent of a terrorist spectacular was intended to wipe out the entire top tier of the cartel. However, the planned massacre turned out to be a failure when Daniel Kinahan and his top lieutenants escaped. One gang member, David Byrne, was shot dead. Equally unprecedented and shocking was the bloodbath that followed over the next two years. Kinahan and David Byrne’s brother Liam – the gang leader in Dublin – unleashed a small army of hit men who murdered fourteen people. The people living in Dublin’s north inner-city community where the Hutch family came from were terrorized in the process and the real ERU were deployed on the streets to keep the peace.

The Monk was acquitted in 2023 of involvement in the Regency attack and David Byrne’s murder. He has resumed his carefree life in retirement which the row with the Kinahans had interrupted so violently but the madness has cost him dearly. He lost his brother, three nephews and his two closest friends.

The ongoing savagery of the Kinahans has proved another defining feature of the story of crime, which seems to get lost on even the cleverer godfathers: murders are bad for business. Gangland violence attracts more heat from the police than any other crime because it terrifies society and undermines the public’s faith in the State’s ability to protect them. The extraordinary garda response during the feud led to the imprisonment of over eighty members of the cartel in Ireland. Many of them were convicted on their own words as secret garda bugs recorded them plotting murders. The leadership of the gang’s UK operations were also busted and locked away. Ultimately it focused international attention on the Kinahans’ billion euro operation and their corrupt influence over international professional boxing.

They became pariahs confined to their desert bolthole in Dubai after the US authorities offered a bounty for information leading to the arrests and apprehension of Christy Kinahan and his two sons. It placed them at the top of the world’s most wanted list of narcos. In September 2024 the Irish State was using diplomatic and police connections to secure the extradition of Daniel Kinahan and at least one other member of the cartel. I look forward to writing the end of that story when it inevitably arrives.

The war that raged for over ten years between the sadistic McCarthy/Dundon mob and the Keane/Collopys in Limerick was even more horrendous than the Kinahan/Hutch feud. I spent a lot of time in Limerick over the years and at one point the wry joke in the Sunday World newsroom was that I had achieved my initial ambition of becoming a war correspondent.

In the midst of the mayhem the Dundons earned the deserved distinction of being the most savage creatures in gangland history. I labelled them Murder Inc., and wrote a book of the same name. As part of their campaign of terror they deliberately murdered five innocent people either because they got in their way or, with the shocking execution of young mother Baiba Saulite, simply as a personal favour for another gangster pal. I was covering a real life horror show. The murder spree claimed over twenty lives. In both cases whole communities were terrorized and scores more adults and children were left injured and psychologically traumatized. The war also produced an accidental hero in Steve Collins, the extraordinarily brave father of Roy Collins, another innocent victim who was murdered by the Dundons in 2009. The murder was revenge for Steve testifying in court against Wayne Dundon, jailed for seven years for threatening to kill Steve’s nephew in the family pub in 2004. Steve galvanized the people of Limerick when he organized a huge march, demanding an end to the mobsters’ grip on the city. His actions forced the Government to introduce a raft of hard-hitting anti-gang legislation and moved gangland cases into the non-jury Special Criminal Court to avoid the intimidation of jurors. I was honoured to have been able to help Steve by highlighting his campaign. He and his family remain dear friends.

The murder of entirely innocent, decent people was the starkest example of how the new breed no longer observed behavioural boundaries and didn’t care who they hit. The gangs are no longer afraid of the public being part of the collateral damage.

The journey through the evolving crime world has been fascinating and rewarding. It could also be emotionally disturbing, depressing and angering, especially to hear the harrowing stories of the innumerable, often forgotten, victims whose lives were irrevocably devastated by evil deeds inflicted by bad people. I also got to shine a light into the other dark recesses of society where evil hides, through the experiences of victims of domestic abuse, rape and child abuse.

The most disturbing story I ever covered about child sex abuse happened in 1992. A private investigator, Liam Brady, had been hired by a company to secretly record phone calls made by an employee, a seemingly respectable man, that they suspected of being involved in fraud. What the tapes revealed was much more disturbing – the man was part of a paedophile ring. In the recorded conversations he could be heard talking to another man as they discussed abusing children as young as two and three years of age. The subject matter was the most vile and depraved that I have ever encountered.

The gardaí launched a major investigation after Brady reported his findings to them. In one particularly creepy recording the man was talking to his teenage daughter. And while there was nothing explicitly said in the conversation I still recall instantly thinking that he was also abusing her. It was sickening. A file on the case was later sent to the DPP by gardaí attached to a special unit in Garda HQ but it was decided that there wasn’t enough evidence to sustain a criminal charge. The secret recordings could not be used in the case.

A few days after we published the story I was a guest on a popular late-night radio phone-in show with Chris Barry on FM104 where we ran a few clips from the tapes but with the voices disguised. The lines to the show were jammed as hundreds of men and women called to relate their own horrific stories of being abused as children. It was a steep learning experience for me. I remember standing in a queue in the bank a week later when it suddenly dawned that any one of the respectable looking men in front of me could also be child abusers hiding in plain sight. As a parent the experience made me very protective of my kids.

Another investigation which I am most proud of was exposing as a serial paedophile a major godfather called Stephen ‘Rossi’ Walsh in 2006 by telling the stories of his terrified female victims who he raped as children. Walsh was a dangerous criminal who had been a member of the General’s gang. He had also been involved in arson, extortion and accident fraud. Everyone was terrified of him. The publicity gave the victims the courage to testify against him. He was subsequently convicted and sentenced to over twenty years in prison. Writing about the stories of such cruelty and desolation made it hard to remain impartial or detached. And there were other reasons why it became more personal than business.

Since the mid-1990s Irish crime journalism has become a hazardous profession, following the gangland murders of two colleagues and friends, Veronica Guerin and Martin O’Hagan. In 2019 the name of journalist Lyra McKee was added to the list. The threat of violence, intimidation and death became the popular course of action for criminals like John Gilligan who sought to silence the messengers.

The crime beat is the only area of the media where journalists run the risk of being targeted by dangerous people as a result of what they write. On more than a few occasions the menace of gangland violence came too close for comfort to my own door, as it has done to other crime reporters. I had a few close shaves but thanks to a combination of survival instincts, luck and timely interventions and protection from the gardaí, I lived to tell the story. I hold the rather dubious distinction of being the only journalist in the country to receive permanent police protection for over a decade. (See Chapter 14.)

Crime journalists, myself included, have also come in for more criticism than any other area of the trade: from politicians, academics, other (begrudging) journalists and, of course, the criminals themselves. Vincent Browne once wrote: ‘crime journalism is the lowest form of the species.’ At the time he was upset by the fact that we’d accused Patrick ‘Dutchy’ Holland of being the hit man who murdered Veronica Guerin without any evidence. Holland was the assassin. The only reason there was no evidence was that witnesses were too scared to testify.

The most common quibble is that we glamorize the mobsters and the mobs. It is nothing new. In 1837 Charles Dickens, one of the first journalists to write about crime, was castigated when he published Oliver Twist. The critics accused the greatest literary genius in history of glorifying crime. It’s nice company to be in.

Criminals by their nature prefer to reside in the shadows, well out of the spotlight of media attention. One of the lessons I first learned in the years spent covering the story of the General, Martin Cahill, is that gangsters will do anything to preserve their anonymity and avoid exposure in the media. Cahill never went anywhere without his mask.

Being unidentifiable and anonymous provides a layer of protection to the gangster. Like vampires being caught in the sunlight, media coverage can be potentially disastrous. Exposing crime and criminals has an important role in a free society. Public attention on a criminal and their exploits makes life difficult and gives the police greater impetus to come down hard on them. By and large most of the leaders of the gangs are men. There are no known godmothers in Ireland. Testosterone is an important ingredient in the criminal psyche.

When intimidation doesn’t work they resort to their lawyers or complain to the Press Council about some perceived infringement of the codes of ethics. I’ve lost count of the number of threatened legal actions and complaints I’ve received. The vast majority of them went nowhere. Over the years a number of major criminals applied unsuccessfully to the High Court seeking gagging orders against me. They attacked me on websites, in poster campaigns and even on RTÉ’s Liveline. (See Chapter 15.)

These days criminals mostly scurry around like rats in the sewers of social media from where they spew lies and attack the credibility of their accusers. When they go on the offensive you know that you have done something right. As a crime journalist I have always believed the old adage: you only get flak when you’re over the target.

Daniel Kinahan was a prime example of using the social media platforms to spout lies. He even made a ludicrous YouTube ‘movie’ to claim that the 2016 attack on the Regency Hotel by the Hutch gang was the product of a grand conspiracy involving the Irish Government, the gardaí and the media to keep the Kinahans’ favourite political party, Sinn Féin, out of power. Sinn Féin has always wanted to abolish the Special Criminal Court because over the years it was the State’s main weapon against their terrorism. Kinahan even commissioned an online ‘book’, written by some anonymous individual, in which amongst others, I was named as being one of the conspirators. At the time he was particularly exercised by a story I had written for the Sunday Independent. It came from the Hutch clan and outlined Gary Hutch’s knowledge of how Kinahan had double crossed and murdered former business associates in Europe. Daniel had tried to cover up the killings as the work of Russian mobsters.

I have also learned a lot about the psychology of gangsters over the years. One of the things that always fascinated me is how men who control criminal organizations through fear and violence can be terribly thin-skinned when it comes to media coverage. It is a trait shared by every villain I ever encountered, regardless of whether he is a street-level thug or a clever international crime lord. If they can’t lash out physically or issue death threats the vast majority of criminals will instinctively play the victim. Criminal psychologists would describe it as the process of rationalizing their behaviour and the classic defence mechanism of a narcissist.

Daniel Kinahan’s father Christy Kinahan was, like his son, a self-pitying mobster. But even the imperious, well-educated, self-styled gangland sophisticate who speaks several languages proved to be a sensitive soul. I bestowed him with the sobriquet the Dapper Don, in recognition of his dress sense and elevated position in the hierarchy of mobsters. For several years I tracked his trajectory as he became one of the top drug traffickers in the world, highlighting the cartel’s controlling role in organized crime and its international operations.

Kinahan had proved to be an elusive target over the years as he went to great lengths to avoid reporters. I was the first journalist to doorstep the international mob boss when I finally caught up with him in Belgium in 2009. I was waiting for him with a photographer as he emerged from a court in Antwerp. He had just been released on bail after being held in custody for a year while the authorities investigated money laundering offences. A year earlier I had gone to Antwerp to exclusively cover the story of his arrest. The conspiracy included a football club and a number of Belgian police officers. The court had found him guilty and sentenced him to four years. We had been tipped off that he was going to be released because, in the strange Belgian justice system, a felon only has to serve a third of his sentence and Kinahan had served most of that already. The deal was that the authorities would contact him when it was time for him to go in and finish the final months of the sentence.

As he walked with his lawyer on the street I sidled up and introduced myself. The Dapper Don went white in the face but showed no other emotion. He was much taller than me and a known expert in judo so, in the event that he knocked me unconscious, I warned photographer Padraig O’Reilly to ‘get the picture, then call the ambulance’.

As I walked alongside I asked Kinahan what he thought of being classified as one of Europe’s biggest cocaine dealers. Clearly angry at the unwarranted intrusion, he sullenly replied in a cultured European accent: ‘You do not tell the truth. You take information from the police and then write false stories based on that information about me. Therefore I will not be giving you an interview.’

Then he began accusing me of being a drug abuser and hiring prostitutes in some part of Spain I had never heard of. Criminals have a narrow imagination when it comes to hurling abuse and project their own moral code. In a spontaneous reaction, and a moment of madness, I shoved the godfather of international crime with my shoulder to see how he’d take it. I was recording him on my phone as I said: ‘Christy, for all your sophistication you’re no different from all the other scumbags... can you not come up with something more original?’ My life has been punctuated with reckless moments.

I said I wasn’t there to hear about my imagined bad habits, I was there for his side of the story, asking him: ‘Isn’t it time that you put the record straight?’

The Dapper Don said nothing more and walked off. I was delighted that I got what I came for. His pictures were plastered all over the front page of the Sunday World the following weekend.

Eamon Dunne, the serial gangland killer I dubbed the Don was another mobster who felt terribly sorry for himself. Over a period of four years Dunne waded through a river of blood to become one of the most feared figures in gangland. The Don was directly responsible for fifteen murders during his strike for power, including that of his former boss Martin ‘Marlo’ Hyland and of innocent trainee plumber Anthony Campbell, who was in the wrong place at the wrong time. Dunne had also been involved in the organization of the murder of Baiba Saulite.

On 20 January 2009 the paranoiac murdered his best friend and fellow gangster Graham McNally. It was the third murder in the space of a few weeks that he had either ordered or done in person. By that stage he had slain ten former associates and enemies. As gangland’s most prolific killer he was certainly worth an interview. The following day I phoned him to ask about his role in McNally’s killing and the other murders. I’d got his number from a source and decided to chance my arm.

The Don was furious at the intrusion into his privacy and demanded to know where I got his number. I glibly explained that I couldn’t reveal my sources lest they suffer the same fate as his other victims which of course was perfectly true.

Surprisingly he opted to stay on the line as I recorded his every word. Dunne’s responses were typically defensive and evasive. He denied any involvement in the murders and diverted to complain bitterly about the media coverage of his activities, especially the stuff that had appeared in the Sunday World.

Dunne, the serial killer and most feared gangster in the country at the time, put on a human mask and accused me of putting his life at risk. I got a very illuminating interview which bordered on parody. ‘I feel that I am now a target over all of this. I feel unsafe. I don’t know anything about anyone getting clipped,’ Dunne moaned, as he blamed the media and the cops for his predicament.

When I asked if he was aware that his name had been linked to the various murders Dunne angrily replied in a self-pitying rant:

I didn’t murder anyone. What do you mean my name is coming up everywhere as a suspect? I am aware that I am hurt and upset over my friend being killed. I think it is very insensitive of you to be ringing me today after my friend has been killed. I am fearful for myself and my family. I don’t want my friends or his [McNally’s] family to think that I had something to do with it. No one has come to me and said to my face: ‘I am accusing you.’ I didn’t clip [shoot] anyone. I did not murder my friend Mr McNally. He was a good personal friend of mine. How did you get my number and where did you get all the information about me?

Dunne eventually agreed to a face-to-face meeting with me but he wouldn’t take any other calls. A few days later he went to the courts seeking an injunction to stop the gardaí leaking stories about him to the media. Dunne, who fancied himself as a barrack room lawyer, claimed that there was a conspiracy between the press and the police to damage his ‘safety and integrity’. I ran our interview with Dunne on the front page and catalogued his astonishing death toll in the same week. I gave him the nickname the Don and was glad to have contributed to his woes.

In the months following the call the Don ordered the murder of another five associates. The dead included Christy Gilroy, one of his own hit men who vanished in Spain in February 2009 after carrying out the double murders of Dunne’s rival Michael ‘Roly’ Cronin and his friend James Maloney on 7 January. I broke the story of how Gilroy was shot dead and buried in an unmarked grave on the Costa del Sol. He had been killed by another notorious hit man I later exposed, Eric ‘Lucky’ Wilson.

In the stories I revealed how the Don was becoming more unhinged and unpredictable. When he took the macabre, prophetic step of ordering his own casket and grave I got the tip off and shared the news with the readers. Some of my information came from garda sources and also from lower ranking criminals in Dunne’s orbit who were frightened and sick of him. Even criminals like to use the media sometimes to get the story out. My experience told me the Don was running out of road.

Dunne had been an important business partner of the Kinahan cartel and their large Dublin network. But gardaí were clamping down hard on the drug trafficking operation as a result of his murder rampage. Dunne was becoming a pariah in the underworld. His mentor at the time, Eamon Kelly, stood away from him. The veteran gangster, who was one of the pioneers of the original gangland and also a mentor to the Monk as he started out, knew that his protégé was running out of friends. I had been covering the story of Kelly’s life ever since I first began reporting crime. He was the first Irish gangster to be convicted of importing a large quantity of cocaine in the early nineties, long before the drug became universally popular. Around the same time I tried to get an interview with him but he walked away. When I became crime editor of the News of the World in 2010 I had Kelly photographed in the street and named him as the Don’s top advisor.

It was only a matter of who got to Dunne first: the cops or his own ilk. I later revealed how the Don crossed the line when he began threatening people like Gerry Hutch’s best friend Noel Duggan, a likeable rogue who was the top tobacco smuggler in the country, suitably dubbed Mr Kingsize. The Kinahans and their associates, including Gary Hutch, had resolved that Dunne would have to be stopped before he tried to kill one of them. In the traditions of gangland people like Eamon Dunne don’t get sacked, locked away or banished. To borrow a phrase often used by Gerry Hutch, Dunne ‘had to go’. On 23 April 2010 a hit man shot him three times in the face and head as he sat with friends in a pub in Cabra, north Dublin. In a completely separate set of circumstances his mentor Eamon Kelly was gunned down by a dissident republican gang two years later.

The deaths of the veteran villain and his savage protégé exemplified the predictable nature of life and death in gangland in the roughest draft of history, especially the one that has evolved since the start of the twenty-first century. Gangland has an alternative ecosystem where there is no governance or central authority. Although it did not exist in the seventeenth century, the writings of Thomas Hobbes, the father of modern political philosophy, can be interpreted through the prism of modern gangland. In his book Leviathan, published in 1651, Hobbes postulated that in the absence of a lawful authority, where each person would have the right to everything they wanted, civil society would descend into a ‘war of all against all’. In such a world life would be one of ‘continual fear and danger of violent death’ where the life of man would be ‘nasty, brutish and short’.

Over the decades I have chronicled the nasty, brutish and short lives of many criminals who lived outside the realms of civil society. The most infamous anarchist of them all was also the one who confirmed my chosen route in journalism.

His name was Martin Cahill, the crime boss they called the General.

CHAPTER TWO

UNMASKING THE GENERAL

We had been sitting in the van for what felt like an eternity: watching and waiting, poised for action. Several hours had dragged by since the commencement of the secret surveillance operation at 4 a.m. on a chilly October morning. As dawn broke and the south Dublin suburb came to life, its citizens were oblivious to our presence as they hurried past, distracted by the cold and the humdrum routine of life.

Being unobtrusive was central to the plan. Attracting unwanted attention would blow our cover, especially if someone called the cops to report two men lurking suspiciously in a van for hours on a quiet leafy side street. Since taking up position on Oxford Road in Ranelagh close to the target’s home, neither of us had dared move even for a coffee or a toilet break – it wasn’t an option. To mitigate the basic necessities we had come equipped – with a hot flask and a plastic bottle.

Experience had taught us that a momentary lapse in focus could result in missing the most elusive of targets – one who possessed an uncanny sixth sense for secret watchers. The self-inflicted privations and the monotonous hours spent sitting in the same cramp-inducing positions would be worthwhile if we bagged the one scoop that had eluded the Irish media for years – to unmask the hooded bogeyman of organized crime.

That was exactly what I planned to do that day along with my colleague and long-time friend Liam O’Connor – aka the Loc. O’Connor was a tough, experienced snapper who had been working for the Sunday World since shortly after the country’s home-grown cheeky tabloid rolled off the presses to shake up the stuffy Irish newspaper industry.

Liam’s first ever assignment was to capture the horrific carnage and devastation left in the immediate wake of the Dublin bombings of 1974 that left twenty-three dead and hundreds injured and maimed. O’Connor had no compunction doing tricky, dangerous jobs or spending long hours on surveillance which was why we partnered together throughout my career with the paper. Photographer Padraig O’Reilly would also become an integral part of our small, three-member team. Over the decades we unmasked many godfathers.

The target of our clandestine escapade this time was one Martin Joseph Cahill, the undisputed godfather of the Irish criminal underworld, public enemy number one, better known by his sobriquet, the General – and one of the reasons why I became immersed in crime reporting.

It was two years since Cahill had first become a household name after a groundbreaking TV documentary on RTÉ’s Today Tonight introduced the Irish public to the General. It exposed him as the ruthless boss of the most prolific armed crime gang yet to exist in Ireland. The programme was the first time that organized crime had been placed so dramatically front and centre in the public spotlight. Cahill and his associates were filmed in the streets being followed by the masked cops from a special overt surveillance unit called the Tango Squad. The criminals all wore masks too. The scenes were unprecedented on Irish TV. It was watched by over a million people, turning the hooded gangster into a household name overnight – and I was hooked on the story.

When he was confronted by reporter Brendan O’Brien, Cahill was surprisingly loquacious and mischievous. He denied he was the General. When O’Brien asked who he thought the General was, the eponymous anti-hero replied: ‘Some army officer maybe… sure the way the country is these days ya wouldn’t know.’ From then on he was referred to as ‘Martin Cahill, who denies he is the crime boss known as the General’.

The documentary’s release coincided with an unprecedented high-profile police surveillance operation by the Tango Squad that had played out on the streets of Dublin’s southside over several months in 1988.

In January 1988 Cahill and six of his top lieutenants – Eamon Daly, Martin Foley, Seamus ‘Shavo’ Hogan, Noel Lynch, Christy Dutton and John Foy – had been targeted by the new Tango Squad. The unit derived its name from the radio phonetics for T (target). Cahill was Tango One. The maverick garda unit consisted of young enthusiastic cops with orders to antagonize and harass the mobsters around the clock. Everywhere the General and his men went, each one was closely followed by up to six hooded cops. When the seven targeted villains were on the move at the same time over forty cops went with them. Any time Cahill was at home the Tango Squad members would sit outside while others would loiter on the walls at the back.