Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Allen & Unwin

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

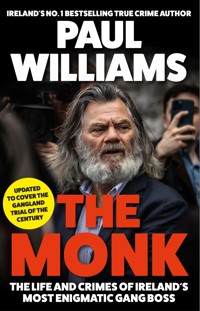

On the streets of the tough Dublin inner-city neighbourhood where he grew up, Gerry Hutch was perceived as an ordinary decent criminal, a quintessential Robin Hood figure who fought the law - and won. To the rest of the world he was an elusive criminal godfather called the Monk: an enigmatic criminal mastermind and the hunted leader of one side in the deadliest gangland feud in Irish criminal history. The latest book from Ireland's leading crime writer Paul Williams reveals the inside story of Hutch's war with former allies the Kinahan cartel, and how the once untouchable crime boss became a fugitive on the run from the law and the mob - with a ?1 million bounty on his head. The Monk is an enthralling account of the rise and fall of a modern-day gangster, charting the violent journey of an impoverished kid from the ghetto to the top tier of gangland - until it all went wrong.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 682

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

______

ALSO BY PAUL WILLIAMS

Gilligan

Almost the Perfect Murder

Murder Inc.

Badfellas

Crime Wars

The Untouchables

Crimelords

Evil Empire

Gangland

Secret Love (ghostwriter)

The General

In memory of Lawrence ‘Larry’ Williams10 August 1937–8 June 2019

First published in Great Britain and Ireland in 2020 by Allen & Unwin

This updated paperback edition published in Great Britain and Ireland in 2023 by Allen & Unwin

Copyright © Paul Williams, 2020, 2023

The moral right of Paul Williams to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

Picture credits: images 1, 2, 10 and 15 © Derek Speirs; 6, 17 and 36 © Charlie Collins/Collins Photographic Agency; 8 and 11 © Irish Independent. The remaining photographs have been sourced by the author.

Every effort has been made to trace or contact all copyright holders. The publishers will be pleased to make good any omissions or rectify any mistakes brought to their attention at the earliest opportunity.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Paperback ISBN 978 1 80546 031 2

E-Book ISBN 978 1 76087 425 4

______

CONTENTS

Prologue

CHAPTER ONE: Clash of the Clans

CHAPTER TWO: Carnival of Crime

CHAPTER THREE: Learning the Trade

CHAPTER FOUR: Power Base

CHAPTER FIVE: First Blood

CHAPTER SIX: The First Big Job

CHAPTER SEVEN: Dirty Money and Murder

CHAPTER EIGHT: A Man of Property

CHAPTER NINE: A New Record

CHAPTER TEN: The Brinks-Allied Job

CHAPTER ELEVEN: Family Business

CHAPTER TWELVE: Operation Alpha

CHAPTER THIRTEEN: The Nephews

CHAPTER FOURTEEN: Stepping into the Limelight

CHAPTER FIFTEEN:A Threat to National Security

CHAPTER SIXTEEN:Dangerous World

CHAPTER SEVENTEEN: Operation Shovel

CHAPTER EIGHTEEN: Treachery and Betrayal

CHAPTER NINETEEN: Countdown to War

CHAPTER TWENTY: The Dogs of War

CHAPTER TWENTY-ONE: The Tapes

CHAPTER TWENTY-TWO: Breakthroughs, Betrayal and Bloodshed

CHAPTER TWENTY-THREE: The Gangland Trial of the Century

Epilogue

Acknowledgments

Index

______

PROLOGUE

The couple and their two children blended seamlessly in the throng of high-spirited passengers disembarking the packed flight from Dublin in César Manrique Airport, Lanzarote on 28 December 2015. They were there as part of the seasonal invasion of Irish folk seeking a sunny post-Christmas respite from the cold and the darkness back home.

The family teamed up with a friend who had arrived on the island the previous day with his girlfriend. Just before Christmas the two men had presented their respective partners with an unexpected gift of an all-expenses paid holiday to ring in the New Year on the Spanish island. As the women looked forward to a week’s fun in the sun, their dangerous partners had a more pressing objective – and it didn’t involve lying by the pool sipping sangria.

The women were blissfully unaware that their seasonal escape had been paid for by the men’s boss, Daniel Kinahan, the leader of one of Europe’s biggest crime cartels, and that this was to be a busman’s holiday.

Kinahan had dispatched the experienced hit men – what Colombians call sicarios – on a high-risk, top-secret mission. The enormity of this decision would be remembered as a seminal event in the history of organized crime back home in Ireland.

The two killers from the north side of Dublin had already proved their ability as cold-blooded, fearless professionals who were prepared to kill anyone just as long as the price was right. And this particular hit held out the promise of a very substantial bounty because it was to be, in gangland terms, a premier league job.

Their target was Gerard ‘Gerry’ Hutch, aka the Monk, one of the most infamous and powerful godfathers in Irish organized crime: in Mafioso parlance, a man of ‘respect’ who no one dared to cross. The relatively few who had foolishly stepped over the line in the past had ended up on mortuary slabs.

Hutch was one of the country’s best-known criminals who had earned celebrity gangster status after masterminding some of the biggest cash heists in Irish history – and getting away scot-free with millions in used, untraceable bank notes.

In the eyes of the law the clever crime boss was not so much untouchable as uncatchable. The people in his old inner-city neighbourhood saw him as a Robin Hood figure while to the wider public, who watched his portrayal in a Hollywood blockbuster and read about his exploits in the media, he was the object of morbid curiosity and fascination.

To Daniel Kinahan, however, Hutch was nothing more than a pre-cancerous spot that required excision before it developed into a terminal tumour. Hutch was a threat to his continued survival and the cartel boss had decided that the Monk was a dead man walking.

By 2015 Ireland’s most successful armed robber had retired from his extensive criminal activities, spending most of the year in Lanzarote where he owned a villa in Puerto del Carmen in the south of the island. After a festive visit back to Dublin Hutch had returned to Lanzarote on 28 December with his wife. The gang boss had a lot on his mind. Dramatic unforeseen events during the year had pulled Hutch reluctantly into the midst of a simmering feud that was not of his making and beyond his ability to control. Unwavering loyalty to family and the transgressions of the younger hot-headed generation had propelled the head of the crime family into the firing line of an increasingly inevitable confrontation with one of Europe’s most powerful gangs.

The seeds of conflict took root over a year earlier when the Monk’s volatile nephew, Gary Hutch, had organized a hit on his one-time close pal and boss Daniel Kinahan in Marbella in August 2014.

The attempt was an unmitigated disaster with the would-be assassin shooting an innocent man by mistake. The finger of suspicion quickly landed on Gary Hutch and he was held prisoner while the crime boss investigated his near miss.

At the insistence of Daniel Kinahan and his father, Christy Senior, the Dapper Don, Gerry Hutch was dragged into the negotiations to save his nephew’s life. A peace deal was hammered out which, in return for Gary’s life, included a payment of compensation and the punishment shooting of the suspected gunman. Pragmatism and reason seemed to have prevailed as both sides withdrew from the brink – or so thought the Monk.

In the end the agreement was nothing more than a ruse to buy time as far as Daniel Kinahan was concerned. He was just waiting for the best moment to take his revenge and it came in September 2015 when Gary Hutch was executed at his apartment complex in Estepona, Spain.

In the months since the murder Kinahan had made a number of approaches to Hutch requesting a parley and further sit downs but the Monk had ignored them. Hutch’s silence had rattled Daniel Kinahan who knew he had awakened a very deadly foe and there was only one way to neutralize the threat – a hit man’s bullet. And that was what brought two of the most effective contract killers in Dublin to Lanzarote on what was supposedly a festive break.

Darkness had fallen on New Year’s Eve when Hutch and his wife arrived in the bar in Puerto del Carmen where he had celebrated his fiftieth birthday two years earlier. The bar was full of revellers partying through the last remaining hours of what had been the Monk’s annus horribilis.

The hit men had already reconnoitred the popular Irish pub, situated just off the main strip on the seafront, where they had the best chance of cornering their wily target when he least expected it. By nature Gerry Hutch was cautious and alert even when at his most relaxed, and the gradual escalation of hostilities between the two sides since the murder had him on his guard. Although he felt relatively safe on the island he knew his enemies had contacts everywhere.

As the Monk scanned the crowd, his eyes locked onto two guys who had just walked in and were ordering a drink at the bar. His body tensed when he recognized the pair. The Monk knew one of them to be a former friend of his nephews and a member of the republican crime gang, the INLA. He had a reputation as a contract killer and a Kinahan loyalist. The pair at the bar pretended not to see their target but a momentary glance in his direction confirmed Hutch’s suspicions – they had come to kill him.

Satisfied that they had their target housed, the hit men promptly left the pub to pick up the murder weapons. They would have plenty to celebrate by the time the clock struck midnight and 2016 arrived.

A few minutes later the killers returned wearing balaclavas and, clutching the automatic weapons under their jackets, made for the spot where Hutch had just been sitting. But the seats were empty and there was no sign of the Monk or his wife. For a moment the killers seemed confused and looked around distractedly, before they fled to the street and vanished.

As the killers left the pub Hutch was already being informed about the drama he had narrowly avoided. His legendary feral street instinct had paid off.

The following day Hutch returned to view the pub’s CCTV footage to get a look at his would-be assassins. It wasn’t difficult to work out who they were – the two men in balaclavas were wearing the same clothing as when they entered the pub looking for their target.

Looking at the CCTV images Hutch realized that a line had been crossed that changed everything and proved beyond all doubt just how perfidious and treacherous the Kinahans were. He knew they would not stop until they had killed him. To get his revenge there was only one law for Gerry Hutch to follow – the gangland law of meeting fire with fire.

The Monk phoned a close confidante to tell him of the events of the previous night and of his next move: ‘Fuck them … if that’s what they want, then that’s what they’re going to get.’

CHAPTER ONE

______

CLASH OF THE CLANS

On New Year’s Day 2016 veteran criminal Gerry Hutch was facing the biggest single crisis of his fifty-two years. The two most powerful family-based gangs in Ireland – led by Irish godfathers Christopher Kinahan Senior and Gerard Hutch – were on a one-way collision course with disaster. The murder of the Monk’s nephew Gary Hutch in September 2015 and the New Year’s Eve attempt against Gerry Hutch himself had ruled out any prospect of reasoning with his one-time close allies. A line had been crossed and they were now deadly enemies.

Hutch, however, had no intention of breaking with his code of omerta to seek help from his old foes, the gardaí, or of instructing his lawyers to threaten legal action. He had no interest in the way disputes are settled in the civilized world beyond gangland’s cultural boundaries. The only law he would invoke was the primal law of vengeance: an eye for an eye. In the immediate aftermath of the failed execution attempt, he disappeared into the shadows to plot the manner and timing of his revenge, beyond the reach of the assassins the Kinahan cartel would surely keep sending until they finally succeeded in closing his eyes – permanently. He knew that when it came to the strike back it would have to be executed with the same meticulous planning and ruthless efficiency of his celebrated heists.

The sensational story of the Monk’s close call in Lanzarote was widely reported in the media back in Ireland. The news was greeted with genuine astonishment by experienced cops, criminals and reporters alike. As crime stories go it could not get any more sensational than that – or so we thought. If someone twelve months earlier had predicted such a confrontation they would, to paraphrase the comedian Billy Connolly, have been sent to the funny farm without getting home for their pyjamas.

Hutch and Kinahan Senior were two of the most devious and intelligent godfathers in Irish organized crime; traits which had helped them to prosper and survive. They had known each other since the early 1980s when they embarked on their respective career paths: Hutch as a street thief turned professional armed robber; Kinahan as a suave petty fraudster turned drug trafficker. Both criminals had been clever enough to learn from the mistakes of their contemporaries who had ended up dead or in prison.

One of the secrets to the Monk’s successful criminal career lay in his talent for self-preservation which involved strategically manipulating circumstances to ensure that he always maintained total control over events. These skills had been the hallmark of his multiple robberies. Losing control inevitably meant failure and the prospect of a long stint behind bars or worse – losing control was not an option. Another secret to his success was that Hutch adopted a pragmatic, methodical approach to solving problems, commenting: ‘When you are in trouble your first priority is to get out of it. Once you have done that you can worry about other things.’ On 1 January 2016 his priority was to regain control of the febrile situation before it was too late.

The master thief’s adherence to a reasoned, non-confrontational approach in business had successfully shielded him from the endemic volatility and treachery that characterized the psyche of the new breed of criminal on Dublin’s streets. It was a tragic irony that it was these same capricious traits in his hot-headed nephew which had ultimately engulfed the Monk’s peaceful world in flames.

It may seem counter-intuitive in the eyes of law-abiding civilians, but Gerry Hutch was an ethical villain who observed a certain code of honour. He exemplified the qualities of a so-called Ordinary Decent Criminal (ODC) – an all but extinct criminal type these days – who played a straight game and kept his word. The ruthless capacity that lurked behind the benign, conciliatory image burnished his reputation as an ODC and a man of ‘respect’. But it was well-known this brutal reaction was only ever deployed when all other avenues of common sense and reason had failed. As a result, the elusive Monk straddled the razor wire fence between gangland and civilized society; he could walk freely on either side and never have to look over his shoulder.

Gardaí who have been trying to catch Gerard Hutch for decades share that view of his character. One veteran cop remarked: ‘He is undoubtedly a villain and one who is capable of vicious violence. But he is also honest, and I think that he was wise enough never to make the mistake of considering himself as being invincible. He is also very focused. He has always been able to compartmentalize problems, dealing with them separately, one at a time.’

In Hutch’s bible treachery was an unforgivable, mortal sin. It breached his strongly-held moral code, an approach he once explained in an interview with crime journalist Veronica Guerin: ‘My philosophy in life is simple enough. No betrayal. That means you don’t talk about others, you don’t grass and you never let people down.’

As far as the Monk was concerned the Kinahan gang had broken this code. Five months earlier, Christy Senior, the Dapper Don, and his son, Daniel, had made a solemn, inviolate pact with Gerry Hutch that in return for financial compensation and a promise of no further retaliation, his nephew Gary’s safety was guaranteed and there would be peace between the two families. The two godfathers had reportedly agreed that they would each keep control on the younger generation to avoid unnecessary bloodshed. It was easy to see why Gerry Hutch was confident that he had a deal and afterwards, according to a friend, warned Gary to stay out of trouble before his impetuous nephew returned to the Kinahan’s stronghold in Puerto Banus in Spain’s Costa del Sol.

And so, when the Kinahans broke the accord by executing Gary and then turning their hit men on the Monk, it was an unconscionable, devastating act of betrayal from which there was no going back. From Gerry Hutch’s point of view, extreme violence was the only option left open to him, with all the unavoidable bloody consequences that would surely follow.

A close friend of the Monk who spoke to him after the failed execution commented:

Gerard was not a guy to come out all guns blazing like the other hotheads because his instinct was to sort out potentially dangerous situations peacefully, talking the problem through with both sides in a calm collective way, a bit like a real-life Don Corleone. He didn’t want people blowing one another up because he was wise enough to know that one killing just leads to another and then another. That’s why he has only ever been connected to a few killings in his time and they were ones that couldn’t be avoided. Gerard always believed that there’s a way of solving problems other than ending up in a casket. But this situation changed everything.

After that [assassination bid] and Gary’s murder he knew he couldn’t trust the Kinahans and everyone around him all agreed with that. The Kinahans are treacherous vipers, especially Daniel, and he got that from his father Christy. Gary had told Gerard of all the people who had been double-crossed by Daniel and his father. Gerard said Christy was ‘a cheap, fuckin’ fraud man who’d do his own mother… you can’t trust him or any of his clan’. In the weeks after the thing in Spain Daniel and Christy denied that they had anything to do with the attempt on his life and they kept trying to arrange meetings with him to talk peace but he knew they only wanted to set him up. He was the one man they feared most because they knew what he was capable of. For Gerard there was no going back. He was in a corner and to protect himself and his family it was a case of kill or be killed. His old way of doing things wouldn’t help him this time. He had a big crew of very able lads around who were more than willing to back him up.

In the first weeks of the New Year, in the midst of much media speculation about the escalating tensions between the two tribes, an eerie calm descended. The Monk had ordered his gang to maintain a low profile while he plotted the next move. This total silence made Daniel Kinahan and his father nervous. Hutch escaping a bullet in Lanzarote was a disaster. They were well aware that he made for a lethal enemy. The wily gangster would never allow them to come so close to killing him again. The Kinahans continued to make overtures to Hutch but they had more immediate concerns.

In a joint venture with UK boxing promoter Frank Warren, Daniel was involved in organizing the WBO European Lightweight title fight which was scheduled to take place in Dublin in early February. Over the years Daniel had been using his dirty money to pursue an ambition of becoming a legitimate international boxing promoter. He had entered a partnership with British-Irish champion boxer Matthew Macklin and set up the MGM gym – Macklin Gym Marbella – from his base in Puerto Banus. Kinahan also managed a stable of boxers. The last thing Daniel wanted was for the highly lucrative venture to be marred by a member of the Hutch gang taking a pot shot at him. There had been much coverage and speculation in the media that the expected escalation in the feud might coincide with the timing of the big fight when the cartel leadership would be together in one place.

In the weeks before the event Kinahan sent two of his closest associates, who had once been close friends of Gary Hutch, to talk with Eddie, the Monk’s elder brother. Eddie ‘Neddie’ Hutch was six years older than the Monk and had been one of his criminal mentors growing up. He brought his younger brother on his first armed robberies when he was still a teenager. Although long since retired, and no longer involved in organized crime, Neddie was still his infamous brother’s eyes and ears. He was the only line of communication the Kinahans had to Gerry who had gone to ground. The young boxing promoter wanted to convince Gerry Hutch that the cartel had nothing to do with the attempt on his life and that they were seeking a truce. Christy and Daniel Kinahan also spoke to Eddie on the phone in an effort to de-escalate the situation and seek assurances that there would be no trouble at the forthcoming boxing title fight. Eddie Hutch agreed to pass the message on to his younger brother who rebuffed the offer because he said the Kinahans could not be trusted. At the same time, the Monk was secretly preparing for vengeance.

When Gerry Hutch made his move a few weeks later, it was unprecedented and ferocious. Just before 2.30 p.m. on a stormlashed, gloomy Friday afternoon on 5 February 2016 – thirty-six days after the botched hit in Lanzarote – a five-man assassination squad stormed the Regency Hotel in Dublin’s northside. In the ballroom about 200 spectators had gathered to attend the much publicized weigh-in for the big fight, billed as the ‘Clash of the Clans’, which was due to take place the following night in the National Stadium, in Dublin’s south inner city. Kinahan and his top lieutenants, including Liam Byrne who ran the cartel’s Irish operation, were there for the big event. The Monk, however, had orchestrated an alternative clash of the clans which wouldn’t conform to boxing’s Queensberry rules.

Three of the killers were kitted out as members of the Garda Emergency Response Unit (ERU), complete with paramilitary-style fatigues, balaclavas, Kevlar helmets and bullet-proof vests emblazoned with the word ‘Garda’. The only difference was that these guys were brandishing AK-47 military assault rifles, the weapon of choice of the IRA. The other two hit men were armed with handguns and posed as a couple, with one of them dressed as a woman.

The ‘Garda’ squad burst into the front lobby of the busy hotel while the ‘couple’ came through a back door into the ballroom. The plan was to trap Daniel Kinahan and his sidekicks by forcing them to flee from the ballroom straight into the path of the waiting ‘ERU’ team who would riddle them with high velocity bullets. Gerry Hutch intended it to be the Irish equivalent of Al Capone’s infamous St Valentine’s Day massacre. Like the fictional Don Corleone in The Godfather, a movie Daniel Kinahan was obsessed with, Gerry Hutch was determined to sort ‘all family business’ in a single devastating blow.

The attack was designed to cause maximum shock and use brutal, overwhelming force to wipe out the cartel’s top management tier in Ireland. With them out of the way the organization would be left powerless and in complete disarray. The Kinahan cartel would be no more. Equilibrium could be restored and peace would prevail.

The ‘couple’ fired a series of shots in the air, creating pandemonium in the ballroom as panicked men, women and children scrambled for the exit doors. On the other side of them, the sight of the fake ‘ERU’ team added to the confusion, giving the spectators the impression that the gardaí had arrived to restore order. But even the best laid plans by successful criminal brains are susceptible to going awry. Daniel Kinahan and his associates fled through an emergency door and got away as the gunman in drag could be heard shouting: ‘He’s not fuckin’ here…I can’t fuckin’ find him.’

The hit team did find David Byrne, the younger brother of Liam Byrne, who was a major player in the cartel. One of the ‘Garda’ team shot David Byrne as he ran with the panicked crowd through the reception area in the lobby. He fell to the ground and tried to crawl for cover. Two of Byrne’s associates were also shot and injured. A second fake ‘Garda’ fired more rounds into Byrne as the other gunmen could be seen on CCTV searching the bar, adjoining rooms and the rear exits for their targets amongst the chaos of the terrified crowd. Reviewing the footage afterwards the shooters seemed calm and completely focused on their task – it was clear they knew who they were looking for.

One of the garda imposters was shown jumping onto the reception desk and pointing his rifle at a journalist who had sought refuge behind it. Satisfied that the terrified man wasn’t a member of the cartel, the gunman casually turned and fired again into David Byrne’s prone body. The thirty-three-year-old criminal was shot a total of six times in the face, stomach, hand and legs. He was so badly disfigured that his family were unable to have an open casket at his funeral.

Realizing that the main targets had escaped, and time had run out, the killing squad retreated to a waiting van outside the front entrance and sped away. The blitz attack was over in six minutes.

Gerry Hutch had established a new inauspicious record for the most audacious attack ever seen in Irish gangland history. His terrorist-style offensive elevated him to a higher level of notoriety. The killers had avoided shooting or injuring any innocent people which illustrated their level of focus and discipline. When examined from the cold-blooded perspective of a terrorist or hired assassin, the attack had been a top-notch professional job.

But after the chaos had subsided and the cordite fumes had dissipated from the lobby of the Regency Hotel, the Monk had to face the realization that it had been a spectacular failure. The senior members of the Kinahan cartel had been left untouched and were already gearing up for a merciless backlash. And Gerry Hutch knew that they had the money, weaponry and soldiers to wage war. He had lost the biggest gamble of his life and the world as he knew it was about to implode.

The attack seemed a reckless escapade given the fact that the links between the pre-fight weigh-in and the Kinahan organization had been so widely publicized. The Monk and his crew would have had to factor in the distinct possibility that armed gardaí would be monitoring the patrons at the Regency Hotel, heightening the risk of a shoot-out. Strangely, however, despite being an obvious public security risk, no gardaí were assigned to monitor the event. It was later deemed an embarrassing and inexplicable oversight. Garda chiefs had planned a major security operation around the National Stadium for the big fight but had not considered the weigh-in a likely flashpoint. It was the only bit of luck the Hutch gang had that day.

While garda management had not considered it necessary to keep an eye on the country’s biggest drug trafficking gang at a major public spectacle in the midst of a simmering feud, photographers and reporters from the Irish Independent and the Sunday World certainly did. They had intended snapping pictures of Daniel Kinahan and his henchmen but what they got instead was a sensational – and terrifying – scoop. As they left, the killers pointed their weapons at the journalists but did not open fire.

The shocking and dramatic images captured by the courageous photographers of the ‘Garda’ team storming the entrance with AK-47s at the ready and the ‘couple’ running from the building with automatic pistols clearly in sight flashed around the world. Such pictures were normally associated with narco-terrorism in Mexico or Colombia but not on the streets of a civilized EU democracy.

The publication of the stark iconic images caused a major public outcry. The uproar could not have come at a more inconvenient time for government politicians who were in the middle of a keenly-contested general election campaign. As questions were asked, it became clear that in the eight years since the economic collapse An Garda Síochána had been starved of resources and one of the consequences was that criminal intelligence gathering had fallen between the cracks. The outgoing government got the blame for plunging Ireland into a policing crisis as outrage grew that criminals were prepared to carry out such brazen, violent acts on the streets of Dublin in full public view.

The government’s immediate response was to open the purse strings and give gardaí whatever resources they required to launch a counter-offensive and bring the offenders to justice. The embarrassment over events at the Regency Hotel also stiffened the resolve of the gardaí to regain public confidence by launching a large-scale assault on the feuding mobs. The Kinahan/Hutch feud, as it became known, would be a three-sided conflagration involving the two gangs and the State. Having enjoyed a long absence, Gerry Hutch was now back at the top of Ireland’s ‘Most Wanted’ list.

But the reaction from the State was the least of his worries. The Monk had factored in an inevitable visit from the gardaí after the shooting. That didn’t bother him; he was adept at picking out a spot on the wall and saying nothing for days on end while in custody. It was the expected backlash from the Kinahans and Byrnes that most concerned him and his associates.

The ferocity of the Regency attack had shocked the Kinahans and their associates. They knew Hutch was dangerous but had never dreamt that he would launch such an audacious paramilitary-style strike. It took them 24 hours to regroup and assess their next move. The Byrne gang, made up of close family relations, was traumatized by the murder of David and was baying for blood. The night after the murder a female relative of the dead man, in her quest for someone to blame, settled on the media and demanded that two journalists be shot. But cool heads prevailed after the threat leaked back to gardaí and they reminded the Byrnes of what had happened to the Gilligan gang after they murdered journalist Veronica Guerin twenty years earlier. In any event there were plenty of others to hold accountable.

Apart from his own anger and upset at the murder of his friend, not to mention the attempt to kill him, Daniel Kinahan was also counting the financial cost of the attack. Within hours of the incident senior gardaí ordered the cancellation of the big fight. The young mob boss had lost out on an event which would have given him a big pay day and a lot of prestige in the boxing game. The presence of the hated media had also led to another negative repercussion. The dramatic images of the attack at the pre-fight weigh-in made headlines around the world focusing an uncomfortable spotlight on the contamination of the sport by an organized crime boss.

Daniel Kinahan and Liam Byrne wanted immediate and implacable vengeance. They issued orders to wipe out Gerry Hutch and everyone belonging to him. The cartel was about to unleash a small army of contract killers in an unprecedented cycle of bloodletting and violence that would turn Hutch’s north inner-city home turf into a war zone. Anyone bearing the name Hutch, or those aligned to them, was fair game in the hostilities that were about to erupt – and they wasted no time getting started.

Just three days after the attack, Gerry’s brother Eddie was gunned down at his apartment at Poplar Row in the heart of the Hutch stronghold in Dublin’s north inner city. The killer showed no mercy as the fifty-eight-year-old taxi driver was shot several times in the head. His murder was greeted with shock and revulsion by local people and gardaí. Eddie Hutch was described by those who knew him as a friendly, harmless individual; he was a soft target who bore the Hutch name. It would later transpire that Eddie was not quite as uninvolved as everybody thought.

It wasn’t that surprising the cartel went after Eddie as he had been acting as an intermediary between his younger brother and the Kinahans. Detectives described the killing as ‘very personal’, highlighting the fact that the assassin deliberately tried to inflict similar horrific facial injuries to those suffered by David Byrne. It was intended as a grotesque reciprocal gesture so that the Hutches, like the Byrnes, could not have an open casket at Eddie’s funeral.

The murder was a shattering blow for Gerry Hutch who had been very close to his brother. Eddie and another older brother, Patsy, Gary Hutch’s father, had been role models for the Monk when they were kids. They were well established as local thieves when eight-year-old Gerry came of age and got caught for the first time by the police.

The night after Eddie’s shooting the Monk sat alone in total darkness in the front room of his home in the seaside suburb of Clontarf, in north-east Dublin. He was watching for his enemies as he tried to work out his next move. Although he did not show any emotion, he was in turmoil. A friend who spoke to him that evening said: ‘Gerard didn’t show emotion because he was programmed that way, but you knew he was on fire inside. It was probably the only time in his life that he seemed to be losing control of things.’

The murders of his nephew and brother had swept away the old assumptions – Gerry Hutch was no longer untouchable. He was still a man to be feared and respected but the protective screen that his standing in the criminal hierarchy had provided to his family and friends lay shattered in smithereens. Now every wannabe gangster who could handle a gun would be lining up to have a pop at the gangland legend. To borrow from the observations of W. B. Yeats on the fallout of a more honourable conflict, all had ‘changed, changed utterly’.

CHAPTER TWO

______

CARNIVAL OF CRIME

The streets where Gerry Hutch grew up in north inner-city Dublin were swarming with police as hundreds turned out for the funeral of his brother Eddie on 19 February 2016. It was probably the first time in the Monk’s criminal career that he was glad to see the gardaí.

Before the funeral, garda sniffer dogs had swept Our Lady of Lourdes Church on Seán McDermott Street for explosives. A similar search had been carried out in Glasnevin cemetery. Officers from the real Emergency Response Unit, whom Hutch’s gang had dramatically imitated exactly two weeks earlier, toted machine guns and automatic pistols as they manned checkpoints in an outer protective ring. A public order unit was parked offside on a side street. Dozens of uniformed gardaí and armed detectives were positioned close to the mourners for fear of another attack.

A garda helicopter clattered above as the Hutch family, neighbours and friends walked behind the coffin on the short journey to the church from his sister’s home on Portland Place, where Eddie had been waked the night before. The gardaí were determined that there would not be another murderous gangland spectacle at the ceremony.

A similar security operation had been put in place for the funeral of David Byrne – ‘Happy Harry’ as he was known – four days earlier. Garda sniffer dogs had searched the St Nicholas of Myra Church on Frances Street across the River Liffey in Dublin’s south inner city. It was the heartland of the Kinahan operation in Ireland and was where Christy Kinahan’s two sons – Daniel and Christy Junior – had grown up in the Oliver Bond corporation flats. But the heavy police presence and the brutality of the two deaths, along with the intensive media scrutiny, were the only similarities between the two high-profile funerals.

In a tacky, vulgar display of wealth, the Kinahan and Byrne gang members, decked out in expensive matching suits, strode defiantly through the streets behind the €18,000 sky-blue casket. Among them were some of the most dangerous and experienced killers in gangland. They had been well-blooded in a previous Dublin gang war, the Crumlin/Drimnagh feud, which claimed over a dozen lives. Afterwards a convoy of eleven stretch limos had followed the hearse from the church, escorted by a bikers’ club.

The sense of menace and intimidation was palpable at the mafia-style funeral – and it was clearly intentional. Daniel Kinahan and his mob had used the event to demonstrate to the world that they were the top tier of organized crime in Ireland. They saw themselves as the meanest, most glamorous bastards on the streets. It represented a contemptuous two-fingered gesture to the media, the police, the public and, of course, the Hutch gang. The cartel relished the huge police presence and the media attention. It was a prime example of the theatrics to be found in what cultural criminologists describe as the ‘carnival of crime’ – David Byrne’s funeral was a ritualized celebration of the gang’s oppositional value system.

By comparison there was no display of self-indulgent hubris at the second high-profile gangland funeral of the week. Eddie Hutch’s send-off was a traditional north inner-city affair. It was a dignified expression of genuine grief as a close-knit community wrapped its collective arm around his family. The only street theatre was the large police presence. Over the coming months there would be many more such funeral processions through the same streets.

In stark contrast to his enemies, the Monk adopted a low profile at his brother’s funeral. The head of the Hutch family was conspicuously absent from the cortege walking behind Eddie’s remains. He wore a black baseball hat, pulled down tight over his face to avoid being spotted by the media. When photographers found him in the crowd he was walking in the company of an old childhood friend and criminal associate, Noel ‘Duck Egg’ Kirwan. Hutch had allowed his once distinctive mop of raven hair to grow so bushy and unkempt that it looked like he was wearing a wig. His dishevelled appearance added to the sense of his dramatic downfall. During the requiem mass he remained in the background, staying away from his family, as his brothers and nephews carried the coffin into the church. Some of them only realized Gerry had been there when they watched the news later that day.

Many there must have wondered what went through Gerry’s mind as Fr Richard Ebejer told the congregation that murder ‘only degrades the humanity of those who carry it out’ and asked, on behalf of the family, that there be no retribution. The priest had made a similar plea at the funeral of Gary Hutch four months earlier. As Fr Ebejer acknowledged it had fallen on deaf ears: ‘It was a request that unfortunately has not been respected, with the result that now more families are in bereavement. They [Hutch family] now call on everybody for this cycle of violence to stop, and to stop now.’

Perhaps if he had had time, Gerry Hutch would have pointed out to Fr Ebejer that the Kinahans were the ones who had ignored the plea for peace when they sent their murderers to assassinate him in Lanzarote. The Monk might have told the priest and the community present that he had been left with no choice – retaliation was the only way he could protect his family.

The attempted massacre at the Regency Hotel had the full support of members of the clan, some of whom also took part in the audacious attack. Gerry Hutch might have been tempted to get up on the altar and apologize for the spectacular miscalculation that had brought so much grief to his family’s door and the shadow of fear and danger it had cast over his beloved home turf. But Hutch, a man who preferred silence over eloquence, had more pressing matters to hand. After the funeral he slipped back into the shadows and would later go into hiding outside the jurisdiction, moving between bases and safe houses across the UK and Europe.

The image of Gerry Hutch at the funeral became a metaphor for his catastrophic change in fortune. The once feared godfather had the demeanour of a man on the run, a hunted fugitive with a bounty on his head. The young criminals who had once admired him were now queuing up to take the murder contracts being offered by the Kinahan gang to wipe out his family. A close associate or Hutch family member was worth a reported €10,000 and all the cocaine the killer could shove up his nose. But the biggest prize was reserved for the elusive Monk. Liam Byrne and the Kinahans subsequently offered €1 million to any criminal gang in Europe who could catch the fugitive gangster. The conditions for payment were that the Monk be taken alive and delivered to Byrne who wanted to personally give him a long, slow and agonizing death.

Less than a year earlier Gerry Hutch held an impressive record that bucked the trend in the criminal underworld. His rigid self-discipline and innate cleverness had helped him to navigate into the safe harbour of a comfortable retirement. During his life he had lost a lot of friends and associates, people who had been mentors or business partners at various stages in his career. Some of them had been assassinated, either by rivals or shot by the police during botched robberies. Hutch had attended a lot of funerals in his time and reckoned he had learned from others’ mistakes. And now here he was reduced to hiding out, in a nightmare that he could never have dreamt up. As the Monk faced an uncertain, perilous future he must have wondered where it all went wrong.

________

‘As a kid, like I mean, me first conviction was for stealing a bottle of red lemonade. I got a fine and then I was involved in other crime as a kid stealing and breakin’ into shops,’ Gerry Hutch commented in March 2008. He was being interrogated by RTÉ crime correspondent Paul Reynolds in the only interview the gang boss ever gave for TV.

In the interview the Monk was uncharacteristically open about the criminological roots of his life which ultimately saw him steal his way out of the grinding poverty of the Dublin ghetto that was his birthright. He was recalling his inaugural criminal conviction for larceny on 30 November 1971 when he was a mere eight years old. As he stood beside his mother Julia in the Children’s Court, having pleaded guilty, the judge fined him £1 and applied the Probation of Offenders Act which was meant as a caution. It was supposed to encourage young first-time offenders to mend their ways. But the initial warning, and the many others Hutch subsequently received in the same courtroom over the years, did nothing to deflect him from his path. By the time he was eighteen he had amassed another thirty convictions for assault, larceny, car theft, joy riding and malicious damage. He served a total of ten custodial sentences in St Patrick’s Institution for young offenders and Mountjoy Prison.

Having had little formal education, prison became the source of his primary, secondary and third-level education. ‘I taught myself to read and write, firstly by reading comics and then books,’ he once recalled. Prison also completed his criminal education which he passed with flying colours.

The young criminal was born on 12 April 1963, the sixth of eight children – five boys and three girls. Patrick and Julia Hutch and their children, like the majority of their neighbours, were forced to live in squalid poverty. Their home was Corporation Buildings on Foley Street in Dublin’s tightly-knit north inner city. The area was bordered on one side by the once thriving docks and on the other by O’Connell Street, the capital’s premier boulevard. The area had been blighted by poverty, deprivation and neglect since the poor first colonized the zone in the early nineteenth century. Families were crammed into crumbling tenement hovels that had once been the grand homes of the social elite of the British Empire’s second city. By 1936, Dublin was described as having the worst slums in Europe.

A purpose-built flat complex, Corporation Buildings had been constructed in 1900 as part of a slum clearance programme but by the 1960s it had degenerated into a semi-derelict, over-crowded tenement on the brink of being condemned. The eight Hutch children slept in one room in a damp, poky flat that was falling down around them. The electrical supply worked intermittently, and the residents had to share a primitive toilet and water tap in the back yard. Patrick Hutch, who was known as ‘Masher’, worked as a labourer on the docks unloading coal and slack from the ships. The backbreaking work involved shovelling up to 50 tons of slack or coal in a single shift. For hours of hard graft the labourers who were classified as ‘non-button coalies’ were paid a meagre wage that was barely enough to feed and clothe the families of workers. Going without the basic essentials of life was common in the neglected socio-economic wasteland of the north inner city.

Long before Gerry Hutch or his siblings were born a criminal subculture had developed in the area which could be traced back to the first tenements in the previous century. The neighbourhood around Corporation Buildings, encompassing the backstreets of Corporation Place, Foley Street and Railway Street, was once the centre of the infamous Monto area, the biggest red light district in Europe. The new Irish Free State with its rigorous adherence to Roman Catholic doctrine shut it down in 1925, forcing the prostitutes out of the brothels and onto the streets. According to a contemporaneous newspaper report, crime ‘and all manner of evilness’ remained rife in the ghetto. But its geographical location meant it could be kept out of sight of the rest of Dublin society, reinforcing the sense of exclusion felt by its inmates.

The same neighbourhood that was Gerry Hutch’s childhood playground also witnessed the era of the notorious Animal gangs. These mobs of unemployed, bored young men, organized along street lines, earned their fearsome name from the bloody street battles fought against rivals from other neighbourhoods. One of the toughest of the gangs came from Corporation Buildings. Knives, potatoes laced with razor blades, knuckledusters and lead-filled batons were the weapons of choice. They wore peaky caps with blades sewn into the brims which they used with devastating effect to slice up their foes – making them the first ‘peaky blinders’. But despite their horrendous reputation for violence most of the Animal gangs observed a strict ethos whereby they did not victimize their own people and often came to the aid of their neighbours by distributing stolen food or preventing evictions. To the locals they were Robin Hood figures in an imperfect world, and the community reciprocated by tolerating the gangs’ violent behaviour.

In his book Dublin Tenement Life Kevin Kearns observed:

Tenement folk, however, regarded these activities as ‘unfortunate’ rather than ‘evil’ realities of life in the impoverished slums. An examination from within the tenement community reveals that these practices were sociologically understandable and socially tolerated under the circumstances of the time… animal gangs were hailed as heroes for their defense of the downtrodden.

The Animal gangs never established lasting criminal empires because in the hungry, jobless thirties, forties and fifties there wasn’t very much to rob or extort, and anyone who did was quickly caught and jailed. The last of the street gangs had faded away ten years before the birth of Gerry Hutch but their exploits had gained legendary status in the rich folklore of the area. The former ‘Animals’ who were still around were objects of fascination for the young Hutch and his friends. They had grown up on a diet of stories about the gangs’ violent antics. He was no doubt impressed by the tales of the violent young men protecting the community and not targeting their own, as a means of creating a secure home base from which to operate. In time the community would also view Gerry Hutch through a similarly ambiguous lens – as an iconic Robin Hood figure whose criminality was understood and tolerated.

When Hutch was born Corporation Buildings still carried its criminogenic label. It was seen as the epicentre of criminal activity in the area by the officers attached to the local Garda C District at Store Street garda station, which had the busiest beat in Ireland. The gardaí were a regular sight on the balconies of the dreary flats as they visited the homes of young and not so young offenders.

Gerry Hutch’s childhood streets also continued to be the focal point of some of the worst levels of unemployment and poverty in the country. Since the early 1960s the indigenous industries in the inner city, such as brewing, glass works, iron works, textiles and the docks, which traditionally relied on the ready supply of unskilled labour in the area, began closing down. Capital investment in the city centre dropped dramatically as industrial imperatives shifted. In the twenty-year period from 1971 to 1991 when Hutch was growing up the inner city experienced a 50 per cent drop in the availability of industrial jobs which exacerbated an already bleak economic situation. The physical environment turned into a wasteland of dereliction adding to the pervading sense of despair. By the early 1980s the process of disinvestment and urban decay had left Dublin’s inner-city landscape pock-marked and scarred, with over 600 derelict sites and buildings.

Outsiders didn’t venture into Railway Street and Foley Street for fear of being mugged and the police officers, as the only symbol of State authority, were seen as the enemy. The Hutch family was deeply rooted in the community and they never left. The area was all they knew – the neighbourhood was their world. Michael Finn was assigned as a rookie garda to the C District in the early 1960s. Over the next three decades he developed a strong bond with the local community and understood why some kids got swallowed up in a cycle of crime. He once explained to this writer:

People who initially got involved in crime did so out of need, running into shops and stealing bits and pieces, sometimes out of hunger. As they grew up, they became a part of different gangs and some were fortunate enough to be weaned away from it. One of the main factors for young people falling into crime was their family conditions. In a lot of cases circumstances were not good, families were dysfunctional, and they had nobody to show them the way. It is an accepted fact that deprived areas will produce criminals. And it is always those areas that the police will concentrate on because criminals live there. Crime is a consequence of how they were reared, where they were reared and what was available to them during their early times.

Gerry Hutch echoed these sentiments in his interview with RTÉ years later. He rationalized why he and his peers began thieving, his words echoing the motives of the generations who preceded him on the same cobbled streets: ‘There was nothin’ around, I mean, first up best dressed, I had no choice. You had to go into crime to feed yourself, never mind dress yourself.’

In 1971, the same year that the young Gerry recorded his first scrape with the law, Corporation Buildings were demolished. The Hutch family moved to Liberty House on Railway Street which was a slight improvement in their living standards. As the State stepped up its well-meaning efforts to resolve the housing crisis one of the unintended consequences was to uproot the bonds that had defined the inner-city communities. Families were separated from friends and neighbours and scattered to sprawling new estates on the periphery of the city. The overall effect of the great migration was a breakdown in social cohesion. The new working-class suburbs had little to offer apart from improved accommodation and quickly became unemployment black spots. Poverty and crime had made the move with the people.

A few years earlier a television programme, The Flower Pot Society, examined the movement of the slum generation and the commentator had accurately predicted the problems of the future: ‘Dublin Corporation are dealing with people all of whom are the same class. It’s much easier to treat them like an army and to transplant them from A to B. They have very little choice in the matter. If a child is to improve it will be in spite of their environment – and not because of it.’

Patrick ‘Masher’ Hutch and his wife had opted to stay put, which would have a profound influence on the young Monk. Anyone who knows him will say that in order to understand the enigmatic gangster you need to understand his attachment to the neighbourhood. He has always expressed a deep affection for the place where he grew up, commenting: ‘I love this area. It’s my home. My heart is here.’ It was a sentiment shared by Ireland’s most infamous crime boss, Martin Cahill, the General, who grew up in corporation flats on the southside of Dublin. He always counselled his henchmen and friends: ‘Never forget where you come from.’

By the time Gerry Hutch was born in the 1960s, successive generations had developed coping mechanisms to counteract the ingrained misery and constant adversity of life in the slums. They had become a remarkably resilient and cohesive community complete with its own rich and complex customs, traditions, survival strategies and urban folklore. People looked out for one another, sharing their own scarce resources with neighbours when their need was more desperate. The hard-pressed mothers such as Julia Hutch were the real heroes who held it all together and did the best they could for their children. When the boys, Gerry, Eddie, John, Patrick and the youngest Derek, started to get into trouble with the law their mother would go to the garda stations, the holding cells and the court to stand by them. Over the years she spent a lot of time in such places. Her three daughters, Margaret, Tina and Sandra, managed to steer clear of trouble.

Early on Gerry Hutch began hanging out with a gang of tough young tearaways from his neighbourhood – ranging in age from ten up to eighteen – who terrorized businesses in the city centre. The group included his older brothers Patrick, John and Eddie. Of the three, Patrick, who was born in November 1960, was almost as prolific an offender as Gerry. Better known as Patsy, by the time he was twenty-one he had amassed twenty-five criminal convictions with the last one in 1982. After that, as far as his criminal record went, Patsy had gone straight.

In 1972 when Gerry turned nine, he appeared on four separate occasions before the Children’s Court on charges of larceny and burglary. While his mother stood alongside him, he was either bound over to the peace or given the benefit of the Probation Act. The following year he was convicted of another three burglaries and was cautioned in each incidence. The young criminal and his associates were making a name for themselves.

On 14 June 1976 Gerry was back in the Children’s Court. He pleaded guilty to a burglary and was sent home with his mother. Gardaí who dealt with the youngster would later recall how he was never particularly cheeky or abrasive when they arrested him. Even at the age of thirteen they recalled how he demonstrated a level of astuteness and intelligence that distinguished him from the other kids he hung around with.

Two weeks after his court appearance in June a gangster movie for kids called Bugsy Malone was released in Irish and UK cinemas and became an instant hit. Child actors played the adult roles in the spoof about Chicago gangster Al Capone, with the bad guys armed with machine guns that fired cream cakes. The movie release coincided with the increasing notoriety of Hutch and his fellow desperados whose prolific crime rate had made them a regular feature at the Children’s Court. A media report compared them to the gang in the movie and the name stuck. The young offenders had found fame and loved it.

Hutch and the other ‘Bugsy Malones’ became prolific burglars and car thieves, before eventually progressing to armed robberies. Hutch dropped out of school as he was busy acquiring a different type of education. The athletic teenagers would rob banks by doing jump overs where they’d race inside, jump over the counter and grab cash from the tills and dart out before anyone could react. They could be in and out of a bank or post office in minutes before vanishing into the warren of inner-city streets that were their natural habitat. In an interview with journalist Veronica Guerin in 1996 Hutch saw nothing abnormal about his teenage exploits: ‘We were kids then, doing jump overs, shoplifting, robberies, burglaries, anything that was going, we did it. That was normal for any inner-city kid then.’

A regular occurrence for the Bugsy Malones was to smash the windows of cars stopped at traffic lights and grab handbags or briefcases from the passenger seats. They were also the first generation of so-called joy riders, dangerously racing stolen cars and jousting with the police during chases. At one stage the joy-riding problem in the north inner city became so acute that officers in the C District were directed not to chase joy riders because of the number of squad cars being rammed and written off. Gardaí were instructed to only give hot pursuit in cases of armed robberies or shootings. Apart from ramming police cars the Bugsy Malones liked to taunt the local officers by sending postcards from sun holidays paid for with stolen money. They would address them to individual officers based in the local garda stations at Store Street and Fitzgibbon Street in central Dublin.

As the Bugsy Malones attracted more media attention a RTÉ radio news programme focused on the gang in a report on the growing problem of juvenile delinquency in Dublin. In a rare display of bravado, the teenage Gerry Hutch bragged about his exploits after leaving the Children’s Court. He bragged: ‘I can’t give up robbin’. If I see money in a car I’m takin’ it. I just can’t leave it there. If I see a handbag on a seat I’ll smash the window and be away before anyone knows what’s goin’ on. I don’t go near people walking along the street… they don’t have any money on them. They’re not worth robbin’.’ And when he was asked what he wanted to be when he grew up, he laughed and replied: ‘I’d like to be serving behind the bank – just fill up the bags and jump over the counter.’

The gang became so notorious that in the mid-1970s it prompted the Department of Justice to open a controversial new prison facility at Loughan House in County Cavan to stem the upsurge of juvenile crime. One of the first inmates to be sent there was Hutch’s best friend Thomas O’Driscoll, who was seven months younger and from St Mary’s Mansions on Railway Street. Another close friend and fellow Bugsy Malone was Eamon Byrne from Sheriff Street.

Gerry Hutch and his compatriots would tell people that they only robbed because living in the north inner-city ghetto they had no job prospects. They weren’t lying. In 1978 the communities within the borders of Sean McDermott Street and Sheriff Street had a youth unemployment rate of 50 per cent, which was the worst in Ireland. It was the same year Hutch turned fifteen – but instead of looking for a job he got his first taste of an adult prison. On 11 May 1978 the Children’s Court sentenced him to twelve months in Mountjoy Prison in the north inner city, for two counts of attempted burglary and possession of house-breaking implements. Established in 1850, Mountjoy has remained Ireland’s