9,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Allen & Unwin

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

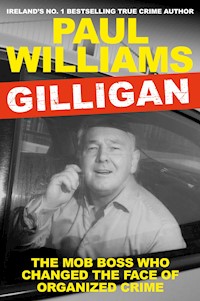

John Gilligan is one of the most notorious and hated criminal figures in Irish history. His name is indelibly etched in the national psyche a quarter of a century after he crossed the line to organise the execution of the fearless, high-profile journalist Veronica Guerin. Gilligan's motive for the assassination was, in the words of the prosecution at a subsequent murder trial, 'the necessity of having to protect an evil empire'. At the time Gilligan was one of the most powerful and feared godfathers in the country who controlled a colossal drugs empire and the underworld's most dangerous mob. Gilligan tells the story of a young man's rise through the ranks of gangland following his journey from petty thief to public enemy number one. He was part of the generation of young criminals - like the General, the Cahills, the Hutches - who ushered in the phenomenon of organised crime in Ireland and became household names in the process. This close-up look at a criminal mastermind contains new details including a graphic account of the planning of the Guerin murder, drawn from a sealed statement which was never used, and the prison time and criminal activity which have occupied Gilligan since, up to his recent arrest in Spain on drug trafficking charges.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

ALSO BY PAUL WILLIAMS

The Monk

Almost the Perfect Murder

Murder Inc.

Badfellas

Crime Wars

The Untouchables

Crimelords

Evil Empire

Gangland

Secret Love (ghostwriter)

The General

First published in Great Britain and Ireland in 2021 by Allen & Unwin

Copyright © Paul Williams, 2021

The moral right of Paul Williams to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

Every effort has been made to trace or contact all copyright holders. The publishers will be pleased to make good any omissions or rectify any mistakes brought to their attention at the earliest opportunity.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Trade paperback ISBN 978 1 83895 489 5

E-Book ISBN 978 1 83895 490 1

Designed and typeset by www.benstudios.co.uk

Printed in

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

CONTENTS

PROLOGUE

CHAPTER ONE:

THE MAKING OF A MOBSTER

CHAPTER TWO:

FACTORY JOHN

CHAPTER THREE:

HEISTS

CHAPTER FOUR:

A GODFATHER OF CRIME

CHAPTER FIVE:

A DEADLY ALLIANCE

CHAPTER SIX:

THE MASTER PLAN

CHAPTER SEVEN:

GETTING STARTED

CHAPTER EIGHT:

THE SOLDIER AND THE GENERAL

CHAPTER NINE:

VICTORY OVER THE LAW

CHAPTER TEN:

GREED

CHAPTER ELEVEN:

THE GAMBLER AND THE MISTRESS

CHAPTER TWELVE:

THE INQUISITIVE CRIME JOURNALIST

CHAPTER THIRTEEN:

PARADISE LOST

CHAPTER FOURTEEN:

UNWANTED ATTENTION

CHAPTER FIFTEEN:

PRELUDE TO MURDER

CHAPTER SIXTEEN:

THE HIT

CHAPTER SEVENTEEN:

PRIME SUSPECT

CHAPTER EIGHTEEN:

THE INVESTIGATION BEGINS

CHAPTER NINETEEN:

BLACKMAIL AND DIRTY TRICKS

CHAPTER TWENTY:

LOOSE ENDS

CHAPTER TWENTY-ONE:

GANG BUSTERS

CHAPTER TWENTY-TWO:

CLOSING IN

CHAPTER TWENTY-THREE:

BATTLELINES

CHAPTER TWENTY-FOUR:

SUPERGRASSES

CHAPTER TWENTY-FIVE:

FACING JUSTICE

CHAPTER TWENTY-SIX:

GILLIGAN’S LAST STAND

CHAPTER TWENTY-SEVEN:

BACK INSIDE

CHAPTER TWENTY-EIGHT:

FREEDOM AND PAIN

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

INDEX

Dedicated to the memory of Veronica Guerinand journalists everywhere who have paidthe ultimate price for doing their jobs

PROLOGUE

20 October 2020, Alicante, Costa Brava, Spain

The grandfather of organized crime had no intention of retiring from what criminals call ‘the life’ on his release from prison. Despite the fact that the sixty-eight-year-old pensioner had spent over seventeen years behind bars and had survived a near-fatal assassination attempt, it was clear that Ireland’s Public Enemy Number One had not yet seen the error of his ways. The brutal mobster, who ordered the murder of a journalist to protect his once powerful criminal organization, was about to hit the international headlines again for all the wrong reasons.

The Spanish National Police like to put on a show when they swoop to arrest what they consider to be a major league godfather – to reassure the public that the good guys are cracking down on the scourge of organized crime. The cameras were all set when they stormed a villa in Torrevieja and busted the leader of a new Spanishbased Irish international drug and gun trafficking operation.

The most notorious and reviled gang boss in Irish criminal history was caught red-handed preparing a consignment of drugs. The raid was the culmination of several months of a joint international investigation, involving the Irish, UK and Spanish police, into the activities of a gang using the postal service to transport cannabis, prescription drugs and guns to the UK and Irish markets.

On the official Twitter account of the Policía Nacional the dramatic images show members of a heavily armed specialist weapons and tactics team (SWAT) piling through the front door after breaking it down. In the kitchen the camera zooms in on their elderly, white-haired target. He has been ordered at gunpoint to lie face down on the floor with his hands cuffed behind his back.

With his face covered with a Covid mask, he is then led to a seat by an officer while the search of the premises continues. He is in shock, looking down at the ground as he comes to terms with his latest predicament which is just about to get a whole lot worse.

On the video the action switches outside as the police make a dramatic discovery that will bring back memories of a shocking crime that took place almost a quarter of a century earlier – and increase the mobster’s chances of getting an even longer stint behind bars this time.

In the garden of the house officers are shown digging up a gleaming silver .357 Magnum revolver. At a later press conference the Spanish police announce to the world that the handgun, an unusual Colt Python, is the same make and model as the weapon used in the execution of Veronica Guerin in 1996. They confirm: ‘Spanish officers are working with the Irish police to determine if it’s the same gun used to end her life.’

The hypothesis is that somehow the mobster has retained the weapon as a memento of the most egregious crime in his fifty-year career. Although he was not named in the police statement about the drug bust or gun find it was obvious who they were talking about.

In custody again, the investigation marked the opening of the latest chapter in the life of Ireland’s most notorious gang boss – an evil criminal known as ‘Gilligan’.

CHAPTER ONE

______

THE MAKING OF A MOBSTER

Special Criminal Court, Dublin, 15 March 2001

The old courthouse building in the centre of Dublin had been the venue for many noteworthy trials in Irish history since it opened its doors in 1797, including those of Irish freedom fighters Robert Emmet and Wolfe Tone. John Gilligan’s trial on charges of murder, possession of firearms and running a multi-million-euro drugs empire was another landmark case. It had been one of the most high-profile trials in the history of organized crime. The three judges of the non-jury, anti-mafia and anti-terrorist court had sat through forty-three days of evidence.

John Gilligan sat in the raised dock looking down into the court chamber with his customary smirk on his face. He was the last member of his once powerful gang to face justice. The mobster, whose rapid ascent as the country’s most powerful godfather ushered in a new era of violent organized crime in Ireland, had been tried in the special criminal court to prevent jury tampering.

On 15 March the judges returned to deliver their landmark verdict before a courtroom filled to capacity with police officers and the media. The judgment had been eagerly awaited as the trial gripped the nation. The courtroom was silent as the chairman, Mr Justice Diarmuid O’Donovan, stated:

While this court has grave suspicions that John Gilligan was complicit in the murder of the late Veronica Guerin, the court has not been persuaded beyond all reasonable doubt by the evidence which has been adduced by the prosecution that that is so and, therefore, the court is required by law to acquit the accused on that charge.

Gilligan had successfully used his favourite weapons of intimidation and fear to beat the rap for the murder of investigative journalist Veronica Guerin. For the same reasons he had also been acquitted of importing large amounts of firearms and ammunition.

The gang boss looked jubilant as he was acquitted of one of the most shocking murders in Irish history. But the three judges wiped the smile off his face when he was convicted of running the biggest drug trafficking operation ever seen in Ireland.

Gilligan had to wait until after lunch to hear his fate on the eleven drug charges. He wasn’t worried. He was confident that with the years he’d already served in prison awaiting trial he would be set free. The court, however, ensured that he would not be resuming his business anytime soon.

The diminutive mobster stood dumbfounded and ashen-faced in the dock as he was sentenced to twenty-eight years behind bars – the longest prison stretch ever handed down to a dope dealer.

Gilligan was taken into custody, leaving the court with a life sentence similar to the one he would have received had he been convicted of murder. The Irish State had shown its determination to put the country’s most notorious and hated criminal out of circulation once and for all.

The conviction marked the denouement of a vast criminal conspiracy that had culminated in the journalist’s murder in 1996 in an act of narco-terrorism which shocked the world. The assassination of the courageous young mother by a professional hit man had an unprecedented effect on the Irish public and caused a universal outpouring of revulsion, fear and anger. The national sentiment was symbolized by the wall of flowers in her memory which the ordinary citizens spontaneously erected at the gates of Dáil Éireann, expressing their outrage and demanding the government take action against mob bosses who considered themselves to be untouchable.

Gilligan had thrown down the gauntlet to the State with the implicit threat that anyone who interfered in his business was fair game regardless of who or what they were: politician, judge, cop, public servant or law-abiding citizen. He had gone far beyond the unofficial rules of engagement traditionally observed in the underworld.

The vast majority of criminals disapproved of the outrage, primarily because they could see it was bad for business and would have negative repercussions for all of them. They were right. The man who had brought a new level of organization to the business of crime would precipitate a fundamental reappraisal of the way international law enforcement and governments tackled the crime lords. The fightback would be spearheaded by the establishment of a revolutionary new body, the Criminal Assets Bureau (CAB), a unique innovation which became a template for similar units worldwide. The CAB would be given draconian powers to strike at the root of what criminality is all about – money.

In Gilligan’s homeland in Ballyfermot, west Dublin, an elderly man watched the TV news report on the gangland trial which had captivated the nation. Gilligan’s trial shone a rare light on the treacherous secret world of organized crime. It had laid bare a story that was both fascinating and shocking, involving intrigue, guns, drugs, violence, murder and money – eye-watering amounts of money. In just over two years Gilligan and his mob had conservatively profited to the tune of over €50 million in today’s values, through the importation of cannabis worth over €250 million on the streets. And those figures did not include money from the sale and supply of other drugs including heroin, ecstasy and cocaine, or firearms. The prosecution had argued that Gilligan’s motive for the murder of Veronica Guerin was ‘the necessity of having to protect an evil empire’.

The TV footage showed a convoy of police and military vehicles whisking Gilligan off to Portlaoise Prison, the State’s maximum-security detention centre. It was a scene that was more reminiscent of the aftermath of an Italian Mafia trial than an Irish one, reflecting the level of threat that he posed to civilized society. Against a cacophony of blaring sirens and clattering rotor blades from a police helicopter, several garda motorbike outriders, prison vans and jeeps carrying heavily armed soldiers raced through the streets of Dublin with the convoy’s VIP – very important prisoner. Watching the spectacle on the TV screen the old man’s mind wandered back in time to the Ballyfermot of 1960 and one of his first meetings with little John Gilligan.

He recalled being out for an evening stroll one night when he spotted a gaggle of excited little kids scurrying from cover at the edge of the golden wheat field that marked the border between the suburban sprawl and the countryside. It didn’t take much deduction to work out that the little terrors were up to no good. They giggled and nervously glanced back into the vast field of wheat that was ready for harvesting.

The man shouted as he saw a single pillar of smoke rising up from the crop about 500 feet into the field. Within minutes the clouds of black smoke were blocking out the sun as flames destroyed the wheat. He recalled:

I will never forget that day. Ever since the kids had moved out to the new council houses they were always messing in that field lighting fires, but this was the worst I ever saw. It was pure devastation.

One of the watching children, eight-year-old John Gilligan, lived on his road and the old man remembers that the boy’s face was full of excitement as fire engines rushed from the city to quell the inferno. When the fire threatened to spread to the nearby houses the boy laughed until tears streamed down his cheeks. This would not be the last time the eight-year-old caused panic and mayhem in his lifetime.

‘When you look back you never think that an innocent kid like that would turn out to be such a gangster,’ the elderly man reflected sombrely. ‘I always thought that he was a grand kid who just dabbled in a bit of ducking and diving...but don’t use my name, I wouldn’t like the trouble,’ he added cautiously.

The insistence on anonymity said a lot about little John Gilligan, the kid who had progressed from childish vandal and petty thief to international drug trafficker and boss of a dangerous criminal empire. Even old neighbours who had always liked and got on well with him and his family feared him. Despite being universally reviled by fellow criminals and law-abiding citizens alike, and safely locked away, a lot of people in ‘Ballyer’ still considered it safer to exercise discretion when it came to expressing their views on the mobster.

It was hardly surprising. Gilligan built his empire and fierce reputation through the use of fear and intimidation. It was how he had managed to escape a murder conviction. But the courts had ensured it was only a partial victory. He would have plenty of time to reflect on how he had ended up facing a rent-free, long-term stay at the pleasure of the State when he had gone to extraordinary lengths to avoid that exact outcome.

_________

John Joseph Gilligan was born on 29 March 1952 in a rundown tenement in Dublin’s north inner city. He was the fifth of eleven children, four boys and seven girls, born to Sally and John Gilligan, who both came from the area. Sally had been a factory worker until 1945 when it was her misfortune to marry John, a petty thief who also worked as a labourer at Dublin docks. John junior’s arrival coincided with a period of mass migration in the 1950s as families were transplanted from the squalor of the inner-city slums to new sprawling corporation estates on the edge of the capital.

The governments of the day had done commendable work in accelerating slum clearance schemes to alleviate the hardship experienced by impoverished Dubliners for centuries. Unfortunately the new public housing projects that gobbled up the countryside in Ballyfermot, Cabra, Crumlin, Inchicore, Donnycarney, Glasnevin and Marino would sow the seeds of a whole new set of social problems.

Despite providing more living space, privacy and decent sanitation, the new peripheral estates had little else by way of social infrastructure. For many of the tenants this was a lonely, alien world, far removed from the cramped streets of Dublin’s inner city. In the move to better living conditions, whole communities were uprooted and broken up.

The overall effect was a breakdown in social cohesion and an unravelling of the close bonds that had characterized the old neighbourhoods. The grinding poverty had also made the journey with them, with the new estates becoming unemployment black spots.

While the vast majority of people adapted and made decent lives for themselves, the gloomy estates also created criminogenic environments which would produce the armed robbers and drug traffickers of the future. It was on the streets of the inner city and the new suburban ghettos where the story of organized crime in Ireland began.

A new generation of young ruthless hoodlums emerged from the social ferment of the late 1960s and early 1970s and pioneered a new world called gangland. In the decades ahead the alumni of this underworld milieu would become household names – for all the wrong reasons.

John Gilligan was one of them.

__________

Gilligan was a baby when his family was allocated number 5, Lough Conn Road, Ballyfermot, in 1952. It was a modest three-bedroom house with running water and toilet facilities. Although a vast improvement on the slums, the new homes were still relatively small for the large families sent to colonize them. In a society dominated by Catholic doctrine, contraception was both illegal and a mortal sin. It was better to create too many mouths to feed among the poorer classes than offend against the moral law.

Lough Conn Road was on the edge of the maze of concrete streets and lines of houses that marked the newly established border between the rural and urban. A few hundred feet away were wheat fields, stretching as far as the eye could see. The open fields were dubbed the ‘Hollywood Hills’ by the newcomers. A kid could ramble across the rustic expanses of Clondalkin, Palmerstown and Ronanstown, which, over the following decades, would also be gobbled up for homes in the voracious urban expansion around the capital.

Like most of their neighbours, the Gilligans arrived in Ballyfermot carrying all their worldly possessions in prams and carts. When the residents began moving in, the infrastructure was still incomplete and the bus service did not go as far as the estates, forcing them to walk the final part of the journey.

Sally Gilligan had a tough life and was left to make the move alone with her five children under the age of seven. Faced with her husband’s indifference and abuse Sally had applied for one of the new houses in Ballyfermot herself. Unusually, she signed the paperwork, which, in a patriarchal era, was seen as the exclusive duty of the man.

John senior had little interest in the welfare of his young family. He was an alcoholic gambler and a professional thief with a penchant for violence. Small in physical stature, like his namesake son, he was regularly absent from home for long periods either because he was in jail or enjoying the life of a ‘bachelor’ crook in the inner city. He squandered his money on booze and racehorses, leaving his wife and children dependent on the charity of others.

Life in the Gilligans’ new home was characterized by deprivation and physical abuse. When John senior turned up, he regularly beat his wife and children in drunken rages. A family member later described how the crook would send John junior down to the bookies to place bets on horses and wait for the results. When his son invariably returned home with bad news, his father rewarded him with a beating. The children didn’t have toys like the other kids on the road and their father’s self-centred profligacy meant they often went hungry.

Gilligan senior was despised as a bully and a thug who, whenever he was broke, had no compunction about breaking into his neighbours’ homes to steal what little they had. The hallmark of his robberies was kicking in a lower door panel with the heel of his boot. One older detective who arrested him recalled how Gilligan couldn’t understand how the police knew so much about him.

Gilligan senior was one of our habitual thieves and he couldn’t work out why we kept catching him. He often gave us information in return for dropping charges. His son obviously picked up a lot of his characteristics. He was a nasty, evil little man.

While the neighbours reviled John senior, his wife and children were popular in the area. A common theme running through the ethnographies of criminal figures is the perception of the mother as the only source of stability in their otherwise dysfunctional and chaotic lives. Sally Gilligan, like many of the mothers in their neighbourhood, was left to raise a gaggle of hungry children, often alone and penniless, while desperately trying to keep them out of criminality.

Locals would recall how Sally Gilligan insisted that her children were turned out clean and tidy in the best clothes they possessed. They were considered good, helpful neighbours. Gilligan junior’s sisters were hard-working girls who helped babysit local children. One time when an elderly neighbour’s wife died, Sally Gilligan ensured that her kids helped out the widower. A former resident recalled, ‘You couldn’t ask for better neighbours than the Gilligans.’

Whenever John senior was in prison the neighbours would warn their children against gossiping about it as an expression of respect and sympathy for his long-suffering wife. ‘I remember my Da saying that that woman was too good for John Gilligan. She was a very quiet, pleasant woman. People didn’t want to add to her misery,’ a former neighbour explained.

As the children grew into their teens, they no longer tolerated their father’s violent excesses, particularly him beating their mother. He was barred from the house until he had cleaned up his act. But by then the damage had already been done to the son who shared his name.

The backdrop of cruelty and turmoil experienced in childhood moulded the man John Gilligan would become. It taught him that violence and intimidation were the most effective tools in life. In his criminal career Gilligan was never known as someone who exercised pragmatism or reason to solve a dispute. He was widely regarded as a loud-mouthed bully, devoid of any class or style. With the subtlety of a bloodthirsty rottweiler marking his territory, his visceral response to any situation was to go on the attack, issuing sinister threats, and to never back down. However, the menacing side to his personality didn’t manifest itself until he had reached young adulthood.

Those who knew Gilligan growing up described him as a pleasant young guy but otherwise quite unremarkable. Some of his contemporaries thought he was not very bright. Gilligan certainly wasn’t a scholar. He attended the Mary Queen of Angels national school in Ballyfermot where his conduct was recorded as good. His teachers found him to be of low intelligence with learning difficulties. He spent more time ‘mitching’ (playing truant) than pursuing his education. He and his pals roamed around the wheat fields and rode the wild ponies and goats which wandered freely on the farms in the area.

Gilligan left school when he was twelve years old with no education and very few prospects for meaningful employment. But Gilligan’s feral instincts and attention to detail more than compensated for a low IQ. Throughout his criminal career garda background reports on Gilligan classed him as ‘cunning and violent’.

In 1966, at the age of fourteen, and at the insistence of his mother, Gilligan’s uncle secured John junior a job as an apprentice seaman. He started with the state-owned B&I Line which had a passenger ferry and freight service operating between Ireland and the UK. It was the only legitimate job he would ever hold. His father also worked for the shipping line, having been employed as a result of who he knew rather than his ability to do an honest day’s work. At this time in his life Gilligan junior had not yet come to the attention of the police and there are no indications that he had begun dabbling in crime. But that was about to change, thanks to his day job. Despite his mother’s best attempts he began to follow in his father’s footsteps.

Gilligan junior teamed up with one of his co-workers, John Traynor. Four years older than his diminutive pal, Traynor had been at sea since the age of fifteen and he helped to show his new friend the ropes. From Charlemont Street in the south inner city, and later nicknamed ‘the Coach’ by Veronica Guerin, Traynor was described as a clever, manipulative and duplicitous gangster who played on both sides of the tracks – with the criminals on one side and the cops on the other.

The Coach had a natural talent for organization and leadership. His smooth talk got him elected to the executive of the Seamen’s Union which effectively ran the shipping company. From behind the protection of this position, Traynor and Gilligan worked together organizing the theft and resale of goods from containers on the ships. The duo also smuggled guns and other contraband from the UK on behalf of their shore-bound associates. It was a partnership that would endure for many years, with deadly consequences.

During the 1970s the B&I Line was, as a consequence of this corruption and mismanagement, being run aground. Successive governments had kept the ailing company afloat with taxpayers’ money. They were told by management that nothing could be done as the company was in the grip of the unions. An internal investigation was launched which revealed that Traynor and the Gilligans, father and son, were part of a network of employees involved in a massive embezzlement racket on board.

A secret survey conducted among passengers illustrated the extent to which the company was being ripped off. On one sailing the manifest recorded 220 passengers, but a head count found that there were actually more than 700 people on board. The little cartel of corrupt workers had pocketed almost 500 fares in just one sailing.

In the early 1980s the then Minister for Transport, Jim Mitchell, reorganized the company and cleared out the fraudsters. By then Gilligan’s seaman’s record showed that he had been officially discharged in 1980 and that his conduct on the high seas had been rated ‘very good’ during thirty-six voyages around the world.

While on shore leave throughout the 1970s he began to get more deeply involved in crime. A year after joining B&I Gilligan had his first scrape with the law when he was convicted of larceny on 3 July 1967. Like many of his contemporaries his maiden crime was rather inauspicious – fifteen-year-old John was caught stealing a farmer’s chickens in Rathfarnham, south Dublin.

On that occasion the District Court judge decided to give the teenager the benefit of the doubt and applied the Probation of Offenders Act (POA). The Act is intended as a slap on the wrist to a first-time offender and an incentive to guide their return to a law-abiding life. Practically every gangster who ever made his mark in Ireland has the POA letters typed alongside their first convictions. Gilligan’s criminal record suggests that he may have actually heeded the warning for a while at least – or was just lucky and didn’t get caught again. It would be another seven years before he next came before a judge.

John Gilligan was eighteen when he met the woman who would one day be described in court as his able ‘partner in crime’. Geraldine Matilda Dunne from Kylemore Road in Lower Ballyfermot was fourteen when she first fell for the diminutive young thief in 1970. A former female friend recalled:

Everyone wondered what Geraldine saw in him – the size of him – but she was mad about him. Everyone thought he was a bit of a gobshite and she was the real brains of the operation.

One of six children, Geraldine was born on 29 September 1956. Like her boyfriend, she dropped out of school when she was twelve. She was described by an old friend as a ‘real live wire’. From the time she was a child she had a passion for horses. It wasn’t unusual to see the feisty teenager galloping bareback on a piebald pony up Lough Conn Road to pick up her boyfriend for a date.

Geraldine worked in a factory making belts and buckles, and later as a basic line operative in a ladies’ underwear factory in Ballyfermot. At lunchtime she would go with friends to see Gilligan, who invariably could be found lounging around the family home when on shore leave. She would ask her friends to tell her employer that she was sick and then spend the afternoon with John. After several sick days she lost her job, so she went to sea for three months with Gilligan, working in the kitchens of a merchant navy vessel.

In January 1974, at the age of seventeen, Geraldine discovered that she was pregnant. On 27 March, two days before Gilligan’s twenty-second birthday, the couple got married in the Church of Our Lady of the Assumption in Ballyfermot. They later moved to live in a flat at the North Strand in Dublin. In September Geraldine gave birth to a daughter, Tracey. A month later Gilligan received his second ever conviction for which he received a six-month suspended sentence for larceny. A year later, in September 1975, the Gilligans had their second child, a son, Darren.

Unlike his father John Gilligan was very protective of his family and took his responsibilities seriously. He decided to knuckle down at his work and provide for them – he more or less gave up going to sea and began robbing full-time. The future drug baron made no secret of his belief that the only way to make money was through crime.

By the mid-seventies he was running with a group of other young criminals who would also make their mark in gangland history. Between them the brat pack ushered in a new era of violence as they became the first generation of organized crime in Ireland.

Among his associates were the Cunningham brothers, Michael, John and Fran, from Le Fanu Road in Ballyfermot. John and Michael were career armed robbers who gained notoriety when they kidnapped Jennifer Guinness, the wife of John Guinness, the millionaire chairman of the Guinness Mahon Bank. John Cunningham later became one of Europe’s top drug traffickers working in partnership with another brat pack member, Christy Kinahan, the Dapper Don. Fran Cunningham, who was nicknamed the Lamb, preferred to spend his time in the fraud game, robbing banks with dud cheques and dodgy bank drafts. Also in the underworld brat pack was up-andcoming underworld heavy-hitter George Mitchell, who was destined to become a major international drug dealer known as the Penguin.

John Traynor introduced Gilligan to his closest friend from childhood, Martin Cahill. The former burglar from Hollyfield Buildings in Rathmines was in the process of becoming one of the most prolific blaggers or armed robbers in the new gangland. His ability to mastermind some of the biggest heists in the history of the State would earn him the nickname ‘the General’.

Gilligan was also associated with members of the Dunne family from Crumlin, the first truly professional armed robbery outfit in Dublin, who in turn introduced Martin Cahill and several other young hoods to the business.

This was the melting pot that produced hard cases like John Gilligan. Such was the homogeneous nature of the nascent organized crime scene that everyone worked together. Associates formed temporary collaborations and provided logistical backup for specific jobs. In the era before the underworld embraced the narcotics trade and wholesale greed and treachery poisoned relationships, there were no murderous gang feuds like those which became the norm from the 1990s onwards.

Disputes were generally settled with a fist fight – a ‘straightener’ – and the villains, despite their enmities, tended to respect each other’s right to life. Murder was not such a casual affair when Gilligan started out in the age of the ODC – ordinary decent criminal.

________

The same year that Gilligan became a seaman, 1966, was to be the end of an age of innocence in a country where crime rates were still among the lowest in the world. The garda crime report for the year recorded that there had been six murders and seven cases of manslaughter which tended to be the result of crimes of passion, domestic disputes or rows over land. There were no armed robberies, with criminal activity confined to burglary, larceny and safe cracking. The Garda Commissioner of the day noted that ‘no organized crimes of violence’ had been recorded and the government was giving serious consideration to closing down prisons, where the daily average population was 300 inmates.

A few years later, however, a new era of violent crime had been declared. In April 1970 an unarmed garda, Dick Fallon, was shot dead during a robbery in Dublin. The killing was the work of the country’s first armed robbery gang, a reckless quasi-republican collection of misfits called Saor Eire. Their inaugural operations took place in 1967 when the young Gilligan was still stealing chickens.

At the same time crimes related to the Troubles, which had flared up in Northern Ireland in 1969, were spilling over into the Republic where the Provisional IRA embarked on a deliberate campaign to destabilise the State and undermine its growing economy. From 1970 onwards the Provos unleashed mayhem, robbing banks, post offices and pay rolls throughout the country to fund their war with apparent impunity. They also carried out murders, kidnappings and bombings.

The sudden surge in serious crime threatened to overwhelm An Garda Síochána, a force which was untrained and ill-equipped to deal with it. On the streets uniformed and plainclothes officers were literally being outgunned by the robbers – the majority of detectives remained unarmed until the early eighties. Being held at gunpoint, pistol-whipped and shot at had become an occupational hazard for gardaí. Over the following years another eleven officers were murdered by Irish Republican Army (IRA) and Irish National Liberation Army (INLA) robbers. As a result the State poured most of its security resources into fighting subversion at the expense of other areas of policing.

And from the shadow of the shadow of the republican gunmen, Gilligan and his peers were watching and learning. The terrorists had opened their eyes to a whole new world of opportunity.

Commensurate with the unfolding law and order crisis was a dramatic upsurge in what gardaí classify as ‘crime ordinary’, or non-political crime, as the former burglars and petty thieves joined in the chaos. The era of the armed robber was firmly established between 1972 and 1978. In that six-year period the number of recorded heists rocketed to over 200 per year and the amount of cash stolen increased fifteen-fold. In a society that operated primarily in cash there were plenty of easy pickings for everyone to get their share. Every Thursday and Friday – the traditional pay days – businesses, financial institutions and the gardaí across Ireland braced themselves for another wave of hold-ups by the terrorist and ‘crime ordinary’ gangs.

There were so many heists taking place that it became something of a joke. In contemporary TV comedy sketches a working-class newsreader character presented a robbery report in the form of a weather forecast. Gilligan later recalled how it was an exciting time to be a young gangster.

At weekends he and the rest of the criminal community would meet on the beach at Portmarnock, north Dublin, for horse trotting races, where they gambled and planned various jobs to recoup their losses. Gilligan was gaining a reputation for violence and was fond of handling firearms. Like his father, he also had a serious gambling problem. Sometimes he combined both vices. In September 1976 he was arrested and charged with an attempted robbery of a bookmaker’s shop on Capel Street in Dublin’s north inner city.

The following year Gilligan and his young family moved to a local authority house in Corduff Estate, in Blanchardstown, west Dublin – one of many such new estates to be built during the decade as the urban sprawl continued. But he wasn’t going to be around to settle in. In July 1977 he received his first custodial sentence, eighteen months, after being convicted of receiving a van load of stolen goods from a shop in Ballyfermot. The following September he got another three months for larceny and a year for the attempted robbery at the bookmaker’s.

A young garda called Tony Sourke had arrested Gilligan on the charge of receiving stolen goods. When Sourke took the thief into the local station to be charged with the offence, the diminutive would-be gang boss warned him: ‘I’ll blow your fucking head off for this.’

John Gilligan was making a name for himself.

CHAPTER TWO

______

FACTORY JOHN

Gilligan adapted to life in Mountjoy Prison once he got over the initial shock of his eighteen-month sentence. His first sojourn behind bars was made bearable in the company of friends from around Dublin who could teach him new tricks. He was also busy planning his future career and how to beat the system.

In November 1977 Martin Cahill, who was already seen as a major player on the gangland scene, arrived. He had been jailed for four years on a charge of receiving a stolen car and two motorbikes which were intended for use in a robbery. His brother Eddie joined them on the same rap.

The following month Gilligan’s old friend John Traynor was also granted a long stay in Mountjoy after he was convicted of possession of a firearm with intent to endanger life. Years later the Coach recalled the incident with typical bravado:

Most of my convictions were for stupid things I did when I was drunk. I was in a pub in Newcastle, outside Dublin and had a .22 pistol which I had bought for £100. I got in a row with a cop who was there. I hit him with the gun and swung it around threatening the people in the bar. It was more of a joke than anything else.

On 14 December 1977 Traynor’s ‘joke’ turned sour when he was sentenced to five years for possession of a firearm, assault, burglary and larceny charges. A few days later he was given another five-year stretch, to run concurrently with the others, for assault causing harm.

Cahill and Traynor were well-seasoned villains compared to Gilligan. They instructed the relative novice on how to play what Cahill referred to as the ‘game’ – his war of wits against the police and the law. Gilligan admired how the psychotic Cahill had no scruples about using intimidation and violence against his enemies, and it didn’t matter who they were. The two criminals had a lot in common. His older mentors taught Gilligan that there were many loopholes in the law which could be exploited using a clever lawyer to fight every step of the prosecutorial process. Trials could also be scuppered by scaring off potential witnesses or simply shooting them.

Gilligan was anything but a slow learner when it came to his criminal enterprise. His record of sixteen convictions, mostly for relatively short jail terms, over a thirty-year period of intense criminal activity demonstrates how he used both legal and criminal means to thwart the law. During the same period he was charged over thirty times with larceny, burglary and robbery. Over half of the cases collapsed when victims and witnesses suddenly developed amnesia.

When he was released from prison in 1978, after serving less than a year of his combined three sentences, Gilligan had decided to focus on a particular area of expertise which had nothing to do with pulling bank heists. He would later declare: ‘I wasn’t into armed robberies because that involved firearms and I could get shot.’

The criminal entrepreneur saw an opening in the market for stolen goods. Working in B&I he’d realized that the container ships were veritable floating Aladdin’s caves, with every conceivable type of resaleable consumer product rolling off their ramps into Dublin. Security was lax and he had solid, corrupt contacts in the shipping business.

Gilligan saw a comfortable niche for himself in the burgeoning Irish crime industry. He would have no problem selling a container load of goods in the working-class estates across west Dublin. The punters would appreciate a bargain and he would turn a tidy profit in a short time.

After his release he established a team of local criminals around him and went to work. Shortly afterwards, one night in November 1978, Gilligan hijacked a truckload of frozen bacon as it left a storage depot at Grand Canal Harbour off James Street in central Dublin. Gilligan produced a .45 pistol and dragged the driver from his cab. He chained the terrified man by the neck to a lamp post and left him there in freezing temperatures.

A few days later Detective Garda Tony Sourke, the young policeman who had arrested him four years earlier, got information that Gilligan was behind the robbery. His informant led him to where Gilligan had hidden part of the haul, behind a ditch in a field near Ballyfermot. The rest of the haul was hidden in a shed. Gilligan had been paying the husband and wife for the use of the shed for several months to hide various truckloads of goods that contained everything from frozen bacon to sheets of galvanized metal, and even nuts and bolts.

The couple were arrested and taken in for questioning. The wife was the first to crack. She described John Gilligan, as ‘a small, little man who wears a big Crombie overcoat’ who had paid them for the use of the shed. Gilligan was arrested and the woman identified him in a line-up in Kevin Street garda station. On 17 November 1978 Gilligan was charged with the crime and released on bail.

Three months later Gilligan was again arrested. This time he was charged with taking part in an armed robbery at the Allied Irish Bank branch on the Naas Road in Bluebell, west Dublin. Cash to the value of €39,000 had been taken in the heist by a team of three armed men.

When Gilligan was questioned he swore on his children’s lives that he hadn’t been involved. His wife, Geraldine, then arrived at the station in tears, pleading her husband’s innocence. She told detectives that Gilligan had been with her at the time of the robbery.

He was subsequently not convicted on either the hijacking or armed robbery charges. In the hijacking case the woman who’d identified him withdrew her statement after Gilligan threatened to harm her and her husband if she testified. In the armed robbery case forensic evidence was not strong enough to sustain the charge and the State bowed out. Before that, however, Gilligan had the audacity to offer a policeman in Ballyfermot a substantial bribe, equivalent to almost €20,000, for the name of the person who had informed on him and his cronies in the AIB robbery. The officer declined the offer.

The detectives were particularly interested in the .45 pistol that Gilligan carried with him on his various jobs. Sometime later they got another tip that he and his team were planning a major heist on Bluebell Avenue near Ballyfermot. Gilligan had arranged the theft of a getaway truck and was to be the driver. As usual a night watchman was to be tied up, the truck loaded, and the cargo taken to a safe warehouse Gilligan had rented in the country.

While a team of detectives from Kevin Street garda station was keeping the area under surveillance, they spotted another group of men hiding in the shadows some distance away. They turned out to be gardaí from Ballyfermot who had received the same information. The informant had been double jobbing. Both teams were after the prize – John Gilligan, his team, the stolen goods and his .45 pistol.

On the second night of the operation the Kevin Street team was about to abandon the job when they spotted the stolen truck pull up outside a flat in Bluebell, not far from the factory. Gilligan was behind the wheel with two members of his mob. They got out and went into the flat. At this stage the backup team for the arrest had moved off.

Detective Gardaí Tony Sourke and Gary Kavanagh decided to move in anyway and arrest the trio in the flat. When they burst in, Gilligan and his two pals were relaxing on a couch. They were arrested and searched, but the woman who lived there was left behind. Outside the detectives found that the truck was empty.

Unfortunately for the police, the thieves had been on their way to do the job. There was no sign of the gun. They later discovered that Gilligan had wanted to open fire when the detectives first banged on the apartment door. He quickly changed his mind and handed the weapon to the woman, who shoved it down her trousers.

Gilligan learned valuable lessons from the close calls and thereafter meticulously planned his future ‘strokes’. He sorted out an impressive network of fences to receive and sell on the stolen goods and sourced hiding places for his loot around Ireland. He made a point of acquainting himself with truckers in a Ballyfermot pub frequented by drivers. They would tip him off about the various cargoes coming in and he would pay them for the privilege of hijacking their loads.

The young criminals soon branched out and began hitting large warehouses and factories in the sprawling industrial estates across Dublin. The Robin Hood Estate in Tallaght, south Dublin, was one of his favourite targets. By now he had earned such a reputation for violence that other criminals would not encroach on certain industrial estates because they were known to be ‘Gilligan’s turf’.

He became expert at short-circuiting alarm systems. Another modus operandi involved lighting a large fire at the exterior wall of a factory or warehouse. The heat from the fire would weaken the wall by drying out the mortar and blocks. The gang would return the next night and easily knock a hole in the wall separating them from the loot.

Gilligan’s robberies during the 1980s were so frequent that alarm and security companies had to develop more sophisticated systems to prevent the heists. But just in case the security system was too elaborate for him, Gilligan had a few security men on the payroll to ensure that things went smoothly.

He planned every aspect of a robbery with painstaking precision and supervised his crew like a military commander. Gilligan knew the layout of every industrial estate he targeted: entry points, escape routes and what each warehouse had inside its doors. He carried out surveillance on each premises and knew the response times of both security staff and the police.

On robberies Gilligan used scanners to pick up garda radio traffic and his teams communicated with two-way radios. Lookouts would be positioned on the approach roads while the other gang members went about cleaning the place out. He became known in the underworld as Factory John. He later bragged:

It was great fun and I got a buzz out of it. Sometimes we got stuff and other times nothing. We were chased by the cops now and again and we had plenty of near misses. There were a lot of times when we were in and out of a place and no one knew a thing for ages afterwards. The strokes [crimes] were a win-win situation for everyone. The owners of the truck or the factory got the insurance money...and me and the lads got a few bob. It was the perfect crime and doing no harm to anyone.

Gilligan’s favourite time of year was winter. The long, dark nights provided excellent cover for a thief. As the evenings grew shorter each year the police in stations covering the big industrial estates braced themselves for a string of burglaries. In November 1981 members of the crime task force attached to Ballyfermot garda station had a lucky break when they spotted Gilligan and two of his pals driving his van near Greenhills Industrial Estate in Walkinstown, south-west Dublin. They stopped the van and found almost €20,000 worth of chocolates which had been stolen from a warehouse. Factory John was stocking up for the Christmas market.

The three crooks were arrested, taken to Ballyfermot and charged with burglary. Gilligan’s van was impounded, and the men were charged and released on station bail pending a hearing in the lower District Court. But Factory John was not giving up the chocolates that easily. The following night an eagle-eyed officer spotted the three hoods in the process of trying to steal the van from the police station yard. The audacious thieves were arrested and charged for a second time.

The following March Gilligan was given a twelve-month prison sentence and banned from driving for fifteen years for using his van to commit a crime and then trying to steal it back from the police. Two months earlier he had been given another twelve-month sentence for burglary.

But Gilligan didn’t mind. The two sentences would run concurrently and he would be out in a few months. He was beginning to play the system. In the course of 1981 Factory John was arrested and charged a total of nine times for larceny and burglary offences. He was convicted of only two crimes.

________

It wasn’t cunning or luck alone that kept Factory John in business. He utilized his favourite ‘get out of jail free’ card – terror and intimidation. Gilligan left his gang members in no doubt of the deadly fate that lay in store for anyone who talked to the police about him.

Standing at just five feet five inches tall Gilligan demonstrated the classic traits of the condition known as ‘small man’ syndrome or Napoleon complex. It occurs where the individual holds a deep-rooted sense of inadequacy about their height and overcompensates with aggressive behaviour. Gilligan did a lot of overcompensating. He would threaten anyone who annoyed him or didn’t give him what he wanted – and it didn’t matter who they were. Gardaí, revenue officials and lawyers were just as eligible for his wrath as an errant gang member.

The aura around Gilligan crackled with menace and volatility. It was a defence mechanism to persuade those that he was meeting for the first time – criminal and law-abiding alike – that size didn’t matter and he could do as much damage as a man twice his height. In street terms he exuded an air of ‘don’t fuck with me or else’. Striking out and dispensing pain were second nature.

According to some of those who worked with Gilligan, he would conduct his own ‘court-martial’ to see if there was an informant in the gang. Once when a member of his gang was arrested for the offence of buggery Gilligan saw him as a potential weak link. In that unenlightened time homosexuality was still a criminal offence and homophobia was embedded in the culture. The police used the law to put pressure on various gangsters who were known to be closet gays. In testosterone-charged gangland, calling a hard man a ‘queer’ was as bad as calling him a tout or informer. The gang member they nicknamed ‘Jeremy Thorpe’, after the British politician who had been at the centre of a gay scandal, was exiled from Gilligan’s inner sanctum. At one stage members of the gang feared he was going to be murdered.

Gilligan was never afraid of the police. When they sat outside his house monitoring his various underworld visitors or searched the place, Factory John would confront them, hurling abuse and threats. His confident aggression was based on the fact that he never brought stolen goods home. After a search he would complain that he was being unfairly victimized by the cops. Often when he was arrested he threatened to murder officers and burn down their homes.

The gardaí wanted the violent armed robber off the streets. In the early 1980s a factory involved in making Atari computer games was burgled in Tallaght. The night before the burglary Gilligan and his crew had set a large fire causing the mortar in the rear wall to crumble. The next night the gang used sledgehammers and a truck to break a hole in it to get into the premises and bypass the security system.

The method was Factory John’s signature and he became the top suspect. A few weeks later the police got a tip-off that Geraldine Gilligan was selling the Atari games to unsuspecting workmates in a factory in Blanchardstown, west Dublin. Detectives from Tallaght identified a woman who had bought one of the games. She made a statement and Geraldine was charged with receiving stolen goods.

Gilligan took over the handling of his wife’s case instructing her lawyers to seek depositions. This is a form of pretrial hearing during which the various witnesses for the prosecution relate the testimony that they intend giving in the actual trial. It was a tactic Gilligan used many times to delay trials. It also gave him an opportunity to convince people that appearing in the witness box would be bad for their health.

On the Friday before the depositions hearing John Gilligan arrived at the home of the woman who had made the statement against his wife. He pushed his way inside and threatened to have her fourteen-year-old son shot if she gave evidence. The woman was deeply disturbed and withdrew her statement the following Monday.

Similarly a nineteen-year-old youth who had bought one of the games pulled out of the case after Gilligan threatened him on the morning of the hearing. The police informed the court of the intimidation but no action could be taken because the victims would not testify.

The case eventually foundered and Geraldine was off the hook. Gilligan openly scoffed at the detectives when his wife walked free. In the meantime Geraldine was fired from her job but her husband made it pay. She successfully sued the company for unfair dismissal and received compensation to the value of €35,000. Then Geraldine went on disability benefit for the stress which she claimed had been caused by the regular police raids on her home. She never worked again.

By the mid-1980s John Gilligan and the Factory Gang were among the top three organized crime gangs on garda intelligence files. Gilligan ranked next to Martin Cahill, the General. The third was the northside-based robbery gang led by a clever young villain called Gerry Hutch, the ‘Monk’.

Intelligence reports describing Gilligan as the most prolific large-scale burglar in Ireland were circulated to detectives in every police division in the State. Gilligan and his associates were being spotted by garda units throughout the country and at one stage it was estimated that he was responsible for one major ‘job’ every week. At any one time Factory John was plotting up to a dozen robberies.

A detective who took a particular interest in Gilligan and would remain his nemesis for over twenty years was Felix McKenna. In 1978 McKenna, originally from County Monaghan, was appointed a detective garda and sent to the Tallaght garda M District. This was the area where Gilligan was committing most of his crimes and he treated the industrial estates as his exclusive turf.

As an investigator McKenna earned a formidable reputation for his abilities and tenacity in pursuing serious crime. He spent practically all of his career involved in the investigation of organized crime and would be one of the founding officers, and later chief, of the Criminal Assets Bureau (CAB).

Shortly after he arrived in the M District, McKenna had his first encounter with Gilligan when he caught him in possession of a stolen lorry and charged him with larceny. The case was dropped when the owner of the truck refused to give evidence after Gilligan threatened him.

On St Patrick’s Day 1981, McKenna and his colleagues thought that they had at last nabbed Factory John. Gilligan and his team stole a truckload of colour TVs from an electrical engineering warehouse in the Cookstown Industrial Estate, Tallaght. At the time the haul was worth over €580,000. Gilligan broke in and disabled the alarm. He reversed a full-length transport lorry, stolen especially for the job, into the factory. After Gilligan and another criminal figure from Ballyfermot loaded it up, they drove the truck to Sligo. It had been arranged that the TVs would be sold to a local businessman who specialized in the sale of smuggled goods – and was a fence for stolen merchandise.

Within a few weeks of the heist McKenna and his colleagues, Detective Sergeant John McLoughlin and Detective Garda Noel Whyte, received intelligence about who had carried out the crime and the name of the fence. By the time the three detectives arrived in Sligo most of the TVs had already taken pride of place in dozens of living rooms.

The unsuspecting customers thought they were getting a bargain smuggled from the North. McKenna and McLoughlin raided the fence’s house and recovered thirty sets. The list of customers included some of the most respected people in the town. Over the following days word filtered out that detectives from Dublin were tracing stolen TVs. For weeks local people were handing in their cherished sets to the local garda station or hiding them in attics. In at least one case, a TV was broken up and dumped.

The Dublin detectives recovered seventy per cent of the haul and charged four people with receiving stolen goods. The fence identified Gilligan as the man who had offered him the TVs and who had actually delivered them. In the end, despite the opportunity of making a deal with the State, the fence opted to take the rap. He had come to the decision after Gilligan and one of his cronies visited him in Sligo, produced a gun and threatened to blow his head off.

Like Gilligan’s other erstwhile ‘clients’, the fence was terrified. The risk of a stretch in prison was better than a spell in intensive care or worse, the grave, he told the frustrated investigators.

It was business as usual for the factory thieves. Demand was booming and the money was flowing in.

Factory John was beginning to believe that he was invincible.

CHAPTER THREE

______

HEISTS

The same year that Gilligan formed his Factory Gang, 1978, also saw the appointment of Dr James Donovan as the head of the State’s forensic science laboratory at Garda HQ, Phoenix Park. The committed scientist spearheaded the advancement and modernization of forensic science so that, by the early 1980s, it had become a crucial component of every major criminal investigation in the country.

John Gilligan was well aware that Donovan’s expert forensic evidence had proved pivotal in securing several high-profile convictions. These included the conviction of the IRA’s top bomb-maker, Thomas McMahon, for the blast in 1979 which killed Lord Louis Mountbatten, his fourteen-year-old grandson, Nicholas, Lady Doreen Brabourne and fifteen-year-old Paul Maxwell. Dr Donovan’s evidence had also helped to convict IRA and INLA members of the murder of three gardaí in 1980.

The scientist was also a crucial witness in several trials involving the ‘crime ordinary’ gangs, like Gilligan’s mob. What the forensic scientist found under the lens of his microscope was often more hazardous to a gangster or a terrorist than the business end of a cop’s .38 revolver. Gilligan and the other mobs had a new enemy and, inevitably, Dr Donovan began to draw unwanted attention.

On the morning of 6 January 1982 Dr Donovan was driving to his workplace in Garda Headquarters when a bomb ripped his car apart. Miraculously the scientist survived the murder attempt. However, Dr Donovan suffered horrific leg injuries which would blight the rest of his life. The motive for the attack was obvious from the outset – some organization or individual didn’t want the forensic expert testifying in court.