19,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: John Wiley & Sons

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

The sociological imagination and the artistic imagination have been historically intertwined, at once reciprocal and conflicting, complementary and tensional. This connection is nowhere more apparent than in the work of Zygmunt Bauman. His conception and practice of sociology were always infused with a literary and artistic sensibility. He wrote extensively on the relationship between sociology and the arts, and especially on sociology and literature; he frequently drew on literary writers in his exploration and elucidation of sociological problems; and he was an avid and passionate consumer and practitioner of art, especially film and photography.

This volume brings together hitherto unknown or rare pieces by Bauman on the themes of culture and art, including previously unpublished material from the Bauman Archive at the University of Leeds. A substantial introduction by the editors provides readers with a lucid guide through this material and develops connections to Bauman’s other works.

The first volume in a series of books that will make available the lesser-known writings of one of the most influential social thinkers of our time, Culture and Art will be of interest to students and scholars across the arts, humanities and social sciences, and to a wider readership.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 586

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

Table of Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright Page

Series Introduction

Translator’s Note

Editors’ Introduction: Culture and Art in the Sociological Imagination of Zygmunt Bauman

NOTES

BIBLIOGRAPHY

1 Culture and Society: Semantic and Genetic Connections (1966)

‘CULTURE’ OR ‘CULTURES’

CULTURE – COLLECTION OR SYSTEM

GENETIC AND EXISTENTIAL RELATIONS

THE MECHANISM OF THE AUTONOMIZATION OF CULTURE

Notes

2 Notes Beyond Time (1967)

I

II

III

IV

V

VI

VII

VIII

Notes

3 Marx and the Contemporary Theory of Culture (1968)

Note

4 Culture, Values and Science of Society (1972)

Notes

5 Jorge Luis Borges, or Why Understanding Is Not What It Seems to Be (1976)

Note

6 Thinking Photographically (1983–1985)

I

II

III

IV

V

VI

7 Einstein Meets Magritte: Postmodernity Is Born (1995)

Notes

8 Assimilation into Exile: The Jew as a Polish Writer (1996)

THE AFTERLIFE OF ASSIMILATION

THE HAUNTED LANDS

LANGUAGE AS SHELTER

ADOLF RUDNICKI OR, POLES LIKE JEWS

JULIAN STRYJKOWSKI, OR THE DUTY TO REMEMBER

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Notes

9 Beyond the Limits of Interpretive Anarchy (1997)

Notes

10 On Art, Death and Postmodernity – and What They Do To Each Other (1998)

11 Actors and Spectators (2004)

Notes

12 Listening to the Past, Talking to the Past … (2008)

13 The Spectre of Barbarism – Then and Now (2008)

Notes

14 A Few (Erratic) Thoughts on the Morganatic Liaison of Theory and Literature (2010)

Notes

15 On Love and Hate … In the Footsteps of Barbara Skarga (2015)

Notes

Acknowledgements

Index

End User License Agreement

Guide

Cover

Table of Contents

Begin Reading

Pages

iii

iv

vii

viii

ix

x

xi

xii

xiii

xiv

xv

xvi

xvii

xviii

xix

xx

xxi

xxii

xxiii

xxiv

xxv

xxvi

xxvii

xxviii

xxix

xxx

xxxi

xxxii

xxxiii

xxxiv

xxxv

xxxvi

xxxvii

xxxviii

xxxix

xl

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

29

28

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

108

109

110

111

112

113

114

115

116

117

118

119

120

121

122

123

124

125

126

127

128

129

130

131

132

133

134

135

136

137

138

139

140

141

142

143

144

145

146

147

148

149

150

151

152

153

154

155

156

157

158

159

160

161

162

163

164

165

166

167

168

169

170

171

172

173

174

175

176

177

178

179

180

181

182

183

184

185

186

187

188

189

190

191

192

193

194

195

196

197

198

199

200

201

202

203

204

205

206

207

208

209

210

211

212

213

214

215

216

217

218

219

220

221

222

223

234

235

236

237

238

239

240

241

242

243

244

245

246

247

248

249

Culture and Art

Selected Writings, Volume 1

Zygmunt Bauman

Edited and with an Introduction by

Dariusz Brzeziński, Mark Davis, Jack Palmer and Tom Campbell

Translated by

Katarzyna Bartoszyńska

polity

Copyright Page

Copyright © Zygmunt Bauman 2021

Editors’ Introduction © Dariusz Brzeziński, Mark Davis, Jack Palmer, Tom Campbell 2021

English translations of pieces translated from Polish © Polity Press 2021

Polity Press

65 Bridge Street

Cambridge CB2 1UR, UK

Polity Press

101 Station Landing

Suite 300

Medford, MA 02155, USA

All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purpose of criticism and review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher.

ISBN-13: 978-1-5095-4544-5 – hardback

ISBN-13: 978-1-5095-4545-2 – paperback

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

by Fakenham Prepress Solutions, Fakenham, Norfolk NR21 8NL

The publisher has used its best endeavours to ensure that the URLs for external websites referred to in this book are correct and active at the time of going to press. However, the publisher has no responsibility for the websites and can make no guarantee that a site will remain live or that the content is or will remain appropriate.

Every effort has been made to trace all copyright holders, but if any have been overlooked the publisher will be pleased to include any necessary credits in any subsequent reprint or edition.

For further information on Polity, visit our website: politybooks.com

Series IntroductionMark Davis, Dariusz Brzeziński, Jack Palmer, Tom Campbell

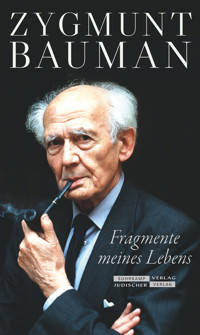

The author of over seventy books and several hundred articles across a career spanning sixty-three years, Zygmunt Bauman (1925–2017) was one of the world’s most original and influential sociologists. In both his native Poland and his adopted home of England, Bauman produced an astonishing body of work that continues to inspire generations of students and scholars, as well as an engaged and global public. Their encounter with Bauman is shaped above all by two books that have acquired the status of modern classics: Modernity and the Holocaust (1989) and Liquid Modernity (2000). While this is understandable, it also means that many readers will be unfamiliar with the great range and diversity of Bauman’s work and with the course of its development over time. Moreover, as Keith Tester argued, an in-depth understanding of Bauman’s contribution must engage seriously with his foundational work of the 1970s, which builds upon his earlier writings in Poland, before his enforced exile in 1968. The importance of this broader and longer-term perspective on Bauman’s work has shaped the thinking behind this series, which makes available for the first time some of Bauman’s previously unpublished or lesser-known papers from the full range of his career.

The series has been made possible thanks to the generosity of the Bauman family, especially his three daughters Anna, Irena and Lydia. Following Bauman’s death on 9 January 2017, they kindly donated 156 large boxes of papers and almost 500 digital storage devices as a gift to the University of Leeds. Anyone privileged enough to have visited Bauman at his home in Leeds, perhaps arguing with him long into the night whilst surrounded by looming towers of dusty books and folders, will appreciate the magnitude of their task. With the support of the University of Leeds, the Institute of Philosophy and Sociology of the Polish Academy of Sciences, Polity, and the Bauman Estate, we have studied this material and selected texts with a view to making them available to a wide readership through the volumes of this series. In partnership with professional archivists and data management experts, we have read, collated and indexed this vast and unique body of material written in both Polish and English since the 1950s. Through this research, we discovered many unpublished or lesser-known articles and essays, lecture notes and module summaries, contributions to obscure publications no longer in print, and partially completed drafts of papers. It quickly became clear that no commentary on Bauman’s life and work to date has been able to grasp fully the multi-faceted and multi-lingual character of his writings.

This series begins to correct that. As well as including many of his lesser-known English-language papers, we have started to tackle the multi-lingual dimension of Bauman’s sociology by working with the translator Katarzyna Bartoszyńska to ensure each of the volumes in this series includes Polish-language material previously unknown to English-speaking readers. This includes more contemporary Polish-language material, with a view to emphasizing Bauman’s continued engagement in European intellectual life following exile.

Each volume in the series is organized thematically, in order to provide some necessary structure for the reader. In seeking to respect both the form and content of Bauman’s documents, we have kept editorial changes to a minimum, only making grammatical or typographical corrections where necessary to make the meaning of his words clear. A substantial introduction by the editors offers a guide through the material, developing connections to Bauman’s other works, and helping to paint a picture of the entanglement between his biographical and intellectual trajectories. This series will facilitate a far richer understanding of the breadth and depth of Bauman’s legacy and provide a vital reference point for students and scholars across the arts, humanities and social sciences, and for his wider global readership.

Translator’s NoteKatarzyna Bartoszyńska

As I have once again found myself translating the work of Zygmunt Bauman, having already translated two shorter works (Of God and Man and Bauman/Bałka) during his lifetime, and one earlier book (Sketches in the Theory of Culture) after his death, I thought I might, at last, allow myself to say something about the way I have approached my task.

Translator’s Notes are relatively uncommon in academic writing, and when they do exist, it is usually to clarify a particular term that is not quite translatable – Heidegger’s Dasein, or Freud’s unheimlich – rather than to defend stylistic choices. But, like so many of the great theorists of culture, Zygmunt Bauman cared deeply about the style of his prose. Although a prolific writer, he was also a careful one, who devoted a lot of attention to crafting his sentences in a particular way. Thus, the work of rendering some texts of his into English is an intimidating prospect, no less so because he wrote the majority of his work in English, and had developed his own approach to the language. I have attempted, in my translation, to cleave as closely to this style as possible – even, occasionally, at the cost of clarity, and thus, some explanation is in order (and a big thank-you to Leigh Mueller, our copy-editor, for helping me to find the right balance).

One of the curious features of the Polish language is that it is grammatically structured in such a way that word order does not determine meaning. Because nouns and verbs are both marked, you can move the words around without creating confusion: pies zjadł kota, kota zjadł pies, zjadł pies kota, zjadł kota pies, kota pies zjadł, pies kota zjadł – though some of these sentences sound distinctly odd, they all clearly state that a dog ate a cat. English is not so permissive, and convention restricts the choices even further, rendering the passive voice, for instance, less common. One of the distinctive features of Bauman’s writing, even in English, is a word order that may seem slightly unfamiliar to English-language readers. Often, this is a consequence of his proclivity for lengthy sentences with multiple subordinate clauses. I have tried to keep these sentences as they are, breaking them into smaller ones only when it seemed absolutely necessary to avoid confusion. I believe that he felt that readers should expend some effort in making their way through longer sentences – that to do so was to participate in a process of unfolding meaning that contributed to understanding it.

I have also chosen to make sentences mostly gender-neutral, using ‘they’ instead of the more cumbersome ‘she or he’. In Polish, human, person and similar such words are gendered masculine, which leads to a de facto use of male pronouns. In his later, English-language writings, Bauman tended to use gender-neutral terms, and I believe he would appreciate that I did the same in this translation. Occasionally, however, the sentence was simply too convoluted without a singular pronoun, so I flipped a coin. And I did preserve some moments when he specifically used female pronouns – a sign that gender inclusivity was on his mind even in the 1960s.

On a more personal note, I translated these texts while living under quarantine during the beginnings of the COVID-19 outbreak. It was the perfect task for such an occasion, and I appreciated the opportunity to work on something that engaged a very specific part of my brain at a time when certain kinds of focus seemed impossible. But, especially, I relished being able to spend time with Zygmunt during this uncertain moment of history, to witness the brilliant creativity and agility of his thought as he returned to various questions throughout the years, and to observe the shifts in his prose style over time. When I hit upon an English phrase that seemed like an especially felicitous rendering of his words, it gave me pleasure to think how he would have enjoyed it. It is hard to believe that it has been over three years since his passing. I miss him. I am glad that this book will give readers an opportunity to get to know him better.

Editors’ Introduction: Culture and Art in the Sociological Imagination of Zygmunt BaumanDariusz Brzeziński, Mark Davis, Jack Palmer, Tom Campbell

In Hermeneutics and Social Science, Zygmunt Bauman (1978) illustrated the multitude of factors that affect human understanding by referring to a visualization technique developed by Gustav Ichheiser, the Polish-born Austrian psychologist. Ichheiser drew an illustration of a windowless room with three doors, each equipped with a light switch that illuminated the room with a different colour: green, red or blue. Ichheiser’s point was that, if three different people entered this same room but through three different doors, they would each flick a switch and hold very different convictions as to the colour of the room. ‘All three reason rationally’, Bauman (1978: 70) stressed, ‘and on the ground of reliable empirical evidence. However, as each is spatially situated in his peculiar way, they arrive at irreconcilable conclusions.’ Bauman recalled this simile almost twenty years later when he was invited by the Polish philosopher Adam Chmielewski to reflect upon his sociological investigations. Bauman stated:

I try to combine the experiences of all these three people; I try to enter the same room each time through a different door. This room is my current society. I entered it once through the door with the inscription ‘the Holocaust’, the other time through ‘ambivalence’, then through the issue of ‘mortality and immortality’, then through ‘moral issues’. Each time it is the same room, but as the light of a different colour turns on each time, its interior changes colour. (Bauman and Chmielewski 1995: 19)

We introduce this volume of selected writings by Bauman on the themes of culture and art – many of which are here published for the first time – by reference to this simile because it illustrates the hermeneutic methodology that sustained his sociological imagination across sixty-three years of writing on almost every aspect of the human condition (Davis 2020; Palmer et al. 2020). Simply put, Bauman steadfastly held to the conviction that ‘Human experience … is richer than any of its interpretations’ (Bauman 2008a: 240).

The hermeneutic method seems to be most appropriate when analysing his own work too. His extraordinary productivity, together with the heterogeneous and multi-thematic nature of his writing, means that we each encounter Bauman for the first time by entering through a different door. Like the character Daniel Sempere in Carlos Ruiz Zafón’s Cemetery of Forgotten Books novels, the requirement to choose a single book to take away and cherish forever has led many to select Modernity and the Holocaust (1989) or Liquid Modernity (2000) as the light by which to illuminate the entire room of Bauman’s sociology. Thus, Zygmunt Bauman becomes the theorist of genocidal modernity, the postmodern thinker, the interpreter of liquid societies (see, e.g., Jacobsen 2017; Rattansi 2017; Davis and Tester 2010; Davis 2008; Jacobsen and Poder 2008; Elliott 2007; Blackshaw 2005; Tester 2004; Beilharz 2000; Smith 1999). Each perspective is valid; but each is partial (Campbell et al. 2018). Each cherished book in Bauman’s vast library provides a snapshot of his sociological imagination, but only in combination and constellation with all of the others might we truly engage in the never-ending process of its interpretation.

As editors of Bauman’s selected writings, in this volume we have decided to ‘enter’ Bauman’s library through a door marked ‘Culture and Art’, two interrelated issues that were very much present in his analyses throughout his sociological career. Bauman stressed many times their significance to his sociological imagination, stating in conversation with Richard Kilminster and Ian Varcoe that culture (along with human suffering) had been one of the two most important subjects of his research (Bauman 1992a: 206), seen also in his better-known reflections on the postmodern and liquid modern conditions (Bauman 2011b, 1997b). With respect to art, Bauman stated:

I’m interested in art for as long as I remember. I was fascinated primarily by visual art. It is related to music and poetry, which differ from visual arts, in my opinion, in the material they process, while the goal is still the same … Art was not a separate field of interest for me, an addition to, or rest from, sociological prose. They were rather two ways of practicing the same profession, differing in the choice of raw material, but not products. (Bauman and Wasilewski 2013: 9)

Bauman’s reflections on culture and art were the inspiration – sometimes the foundation – for his analyses of morality and ethics (Bauman 2009), social and economic challenges (Bauman 2011a) and the condition of social theory (Bauman 2000).

In what follows, we survey the selected writings on culture and art contained within this volume in order to reveal how the evolution of Bauman’s theory of culture and his reflections on art informed his sociological imagination. In introducing these unknown, or lesser-known, pieces of his writing – recently discovered as part of the archival Papers of Janina and Zygmunt Bauman project at the University of Leeds – we begin the process of integrating them into his wider sociology, in the hope of both aiding the reader and encouraging others to assist in this task.

THEORIZING CULTURE

Bauman’s systematic studies on culture began in Poland in the 1960s (Bauman 1965a, 1964), building upon his earliest writings in sociology of politics (Tester and Jacobsen 2005; Bauman 1972a [1960], 1959). Increasingly disillusioned with Soviet-style communism, as well as the politics of the Polish United Workers’ Party and what he lamented as a growing conservative inertia amongst Polish youth (Bauman 1966c; 1965b), Bauman began to play a significant role in the development of ‘humanist’ or ‘revisionist Marxism’ that preoccupied Eastern European intellectuals throughout the 1950s and into the 1960s (Wagner 2020; Brzeziński 2017; Satterwhite 1992; Bauman 1967a). Inspired in particular by the work of Antonio Gramsci (1971), this turn towards the more humanistic elements of the so-called ‘young Marx’ was to have a profound impact upon Bauman’s theory of culture. In rejecting the dogmas that had developed out of the Soviet form of ‘Scientific Marxism’, there began an intellectual search for the truly humanist values of ‘genuine socialism’ which resisted the idea that culture was merely part of wider socio-economic formations. Before his enforced exile from Poland in 1968,1 these developments led Bauman to write two significant books on the theme of culture – namely, Culture and Society: Preliminaries (1966a) and Sketches in the Theory of Culture (2018 [1968]).2 Despite his formal Marxist training, his studies on culture in these two books were inspired by many different sociological orientations: functionalism (Parsons 1951; Malinowski 1944), the school of culture and personality (Linton 1945; Benedict 1934), neo-evolutionism (White 1959; Steward 1955) and structuralism (Lévi-Strauss 1963). From this work, two main interpretations of culture were firmly established, and endured to shape his better-known writings throughout his English-language career (Brzeziński 2020a, 2018b).

First, Bauman defines culture as the sphere of meanings, goals, values and behavioural patterns that are external to the members of a particular group and that exert a compelling influence upon them.3 This idea is expressed in his Polish paper ‘Culture and Society: Semantic and Genetic Connections’ (Bauman 1966b),4 republished in this volume in English for the first time. Here, Bauman distinguishes between ‘attributive’ and ‘distributive’ understandings of culture. In the former, culture is an attribute of human beings that distinguishes them from other species; and in the latter, Bauman stresses the role of culture in establishing differences between groups of various scales. He writes: ‘Culture is the collection of information that is created or borrowed, but always possessed by a given group of humans, transmitted reciprocally among members by means of symbols with meanings that are fixed for that group’ (p. 31). In this paper, Bauman analyses the roles and functions that culture, in its distributive sense, plays in relation to social structure. In curious sympathy with a more functionalist paradigm (Parsons 1951; Malinowski 1944), considering his own vehement critique of this form of sociology (Bauman 1976c), Bauman pointed out that culture is necessary for the harmonious cooperation of members of each society as it serves to unite them, define their identity, and establish common meanings.5 In a manner more multi-dimensional than the classical functionalist approach, however, Bauman argued that culture may fulfil its integrative role for a society only if that society provides conditions for the possibility of achieving such culturally motivated aspirations. As such, one of his main concerns at this time was the genesis, evolution and consequences of a progressive disjuncture between culture and society. He argued that this process reached its peak in modern industrial societies, in which both spheres become autonomous (Bauman 1966a), and he argued strongly for the need to reunite them both (Bauman 1966a, 1965a, 1964).

Second, before his exile in 1968, Bauman also analysed culture in a manner somewhat contrary to the one outlined above. Contra functionalism, Bauman argued that culture is not concerned with the realization of social order, but rather its progressive transformation. In this, we begin to see the significant influence of Gramsci (1971) on Bauman’s theory of culture.6 Reflecting on the formative character of this influence, Bauman later remarked: ‘From Gramsci I learned about culture being a thorn in the side of “society” rather than a handmaiden of its monotonous order-reproducing routine; an adamantly and indefatigably mutinous agent, culture as propulsion to oppose and disrupt, a sharp edge pressed obstinately against what-already-is’ (Tester and Jacobsen 2005: 147). Like Gramsci, Bauman began to perceive of cultural emancipation as the foundation for social and political transformation (Bauman 1967a; see also Brzeziński 2017).7 The development of this second vision of culture was also accompanied by a critique of the positivist vision of human personalities and adopted a more humanistic approach, inspired by Abraham Maslow (1962; see also Bauman 1965a). This theme emerges in Bauman’s article ‘Notes Beyond Time’ (Bauman 1967b), first published in the Polish literary journal Twórczość and reproduced here in English translation. Bauman departs from the formal analytical language of mainstream sociology and develops a more literary voice (a stylistic shift more common in his later ‘liquid modern’ writings) in his criticisms of the ‘reductionist’ portrayal of the human individual in mainstream sociological theories, who emerges from their pages somehow devoid of morality, emotions and the ability to make choices. He writes: ‘Today for the majority of academics, academia is a terrain of escape from choice and risk, a protective fortress against human emotions and impulses, the terrain of monastic escapism from the multiplicity of meaning of human existence’ (pp. 38–9). As a result, Bauman not only emphasizes the need to rethink the sociological relationship between culture and personality, but also presents in embryo some of the ideas that would find their fuller expression in his later works on the commodification of human emotions (Bauman 2003), postmodern ethics (Bauman 1993) and the role of ambivalence (Bauman 1991).

Bauman made several attempts to reconcile these two competing interpretations of culture in his own work, primarily through his encounter with the anthropology of Claude Lévi-Strauss. The impact of these works upon Bauman’s sociology between his exile in 1968 and his arrival in Leeds in 1971 was so significant that he would later label this period ‘Lévi-Straussian’ (Bauman 2018 [1968]: 251),8 stating: ‘The biggest shock for me was … discovering culture as a process rather than as a body of material that was constant, or a set-up for self-stabilization and permanence … The obsessive, compulsive rush to structurization (organizing, ordering, rendering intelligible) of human ways of being-in-the-world appeared to be, from then on, a way of being for cultural phenomena’ (Bauman 2018 [1968]: 252–3; see also Beilharz 2000). Inspired by Lévi-Strauss, Bauman began to theorize culture in the context of the process of ‘structurization’, arguing that culture is a collection of behavioural, axiological and semantic references that provide a certain predictability to human action. He also stressed, however, that these structures do not limit human creativity, but are instead established, modified and shaped by it. Bauman’s dynamic vision of culture as process was thus inspired (and corrected) by Gramsci’s (1971) concept of praxis (Bauman 1973a; see also Kilminster 1979). This relationship between Marxism and structuralism is explored in ‘Marx and the Contemporary Theory of Culture’ (Bauman 1968), also included in this volume. This paper was originally prepared for a Paris symposium taking place on 8–10 May 1968 to consider Marx’s significance for social sciences and the humanities, and which coincided with the first wave of student revolts in the city.9 It is an important piece of writing because the core tension in Bauman’s theory of culture at that time emerges through a criticism of Lévi-Strauss’s conviction that it is the structure of human thinking, rather than the material conditions of human societies, which should provide the basis for the sociological imagination. Remaining true to his Marxist-humanist beliefs, Bauman writes: ‘without renouncing any of Lévi-Strauss’s methodological discoveries, we must try to avoid the blind alley into which he was led by his philosophy. We must designate the reality in relation to which culture – that specifically human aspect of active existence – functions as a sign’ (p. 61).

This affinity towards structuralism endured after his arrival in Leeds. For example, in his Inaugural Lecture titled ‘Culture, Values and Science of Society’ (1972b), republished here, Bauman presents structuralism as the promising way between the Scylla of positivism and the Charybdis of ethnomethodology. Bauman argues that a positivist approach failed to reflect the creative capacity of human beings and, in stressing the structural, institutional and axiological conditioning of social life, led only to the further entrenchment and legitimacy of the status quo. Such an approach was contrary to the transformative potential of culture, which Bauman learned from Gramsci. Ethnomethodology, on the other hand, presented for Bauman only the illusory portrait of human beings as somehow free to shape social reality without restraint. Since both approaches concentrated on a value-free analysis of the rules of interaction constituted within a society, Bauman found no fertile soil in which the seeds of social criticism could grow.10 It was in seeking a way forward beyond both approaches that Bauman developed his well-known theory of culture as praxis (Bauman 1973a). He wrote that human beings ‘overcome their own antinomy only by recreating it and re-building the setting from which it is generated. The agony of culture is therefore doomed to eternal continuation; by the same token, man, since endowed with the capacity of culture, is doomed to explore, to be dissatisfied with his world, to destroy and create’ (Bauman 1973a: 57). Bauman’s approach was highly innovative, pre-figuring the later celebrated work of Pierre Bourdieu’s (1984) structural constructivism and Anthony Giddens’s (1984) theory of structuration,11 as well as proving to be significant for the development of critical cultural studies.

The theory of culture that Bauman developed in the second half of the 1970s was both a study of social transformations and the method best positioned to shape their direction. Influenced by Ernst Bloch (1986), Karl Mannheim (1991) and Herbert Marcuse (1972), Bauman’s (1976b) study of social transformations led him to develop a vision of socialism as ‘the active utopia’, with ‘aspects of culture’ enabling both a constant relativization of the status quo and critical reflections on its possible alternatives. In this context, he wrote: ‘Utopia shares with the totality of culture the quality – to paraphrase Santayana – of a knife with the edge pressed against the future. They constantly cause the reaction of the future with the present, and thereby produce the compound known as human history’ (Bauman 1976b: 12). His Gramscian view of culture is still further revealed by the idea of an ‘active’ utopia standing in opposition to any ‘blueprint’ of the future (Jacoby 2005).12 An ‘active’ utopia is a continuously moving horizon, which shapes the courses of actions driving social transformation but that is never to be reached (Bauman and Tester 2001: 49).13 This is why Bauman’s theory of culture is best captured by the idea of it as ‘a thorn in the side of society’. As he explains: ‘Culture is a permanent revolution of sorts. To say “culture” is to make another attempt to account for the fact that the human world (the world moulded by the humans and the worlds which mould the humans) is perpetually, unavoidably and unremediably noch nicht geworden (not-yet-accomplished), as Ernst Bloch beautifully put it’ (Bauman and Tester 2001: 32).

Bauman’s study of the methods best positioned to direct social transformations was undertaken principally via his exploration of different hermeneutic traditions (Bauman 1978). At that time, and in subsequent writings on the matter (Bauman 1997a, 1989, 1987), Bauman argued that the aim of the process of understanding is not to reach an indisputable, invariable truth. Like an ‘active’ utopia, understanding is also a horizon towards which we must continually strive, rather than a final destination to be reached (Davis 2020). In ‘Jorge Luis Borges, or Why Understanding Is Not What It Seems to Be’, published here for the first time,14 Bauman deploys Borges’s (2000) story Averroës’s Search to meditate on the problem of understanding. He wrote:

However powerful, the intellect enters its task neither innocent nor impartial; it sets about its work loaded with its own past, with some skills sharped [sic] up in the course of its previous jobs, and other faculties dormant or atrophied by the lack of use … Our past – our accumulated tradition – our assimilated experience – is our power and our burden. It must be both at the same time. We can get rid of the constraints it imposes only together with the very capacity of understanding, of acting, of living. (p. 91)

A very important aspect of Bauman’s reflections on hermeneutics was also his conviction that it is not only intellectuals, but all members of any given society, who ought to participate in the process of mutually exploring meaning and understanding. In this context, he praises Jürgen Habermas’s (1987, 1984) theory of communicative action and, partly inspired by the German philosopher, develops his own idea of ‘the culture of dialogue’. For Bauman, this was a general frame through which both communal understanding and patterns of solidarity and collaboration could be achieved. Bauman adhered to this polyvocal vision of culture and language many times throughout his work (Bauman 2016, 2004; see also Brzeziński 2020b; Dawson 2017), ultimately returning to its importance in his final book published shortly after his death (Bauman 2017).

From the early 1980s, Bauman’s theory of culture was interpreted through his wider analysis of modernity (Rattansi 2017; Elliott 2007; Beilharz 2000; Smith 1999). Simply put, culture became a prism through which he analysed the genesis and metamorphoses of modern societies. Inspired by Ernest Gellner’s (1983) distinction between ‘wild cultures’ and ‘garden cultures’,15 Bauman argued in Legislators and Interpreters (1987) that the origin of modernity was motivated by a desire to establish a new structural, institutional and axiological ‘will to order’ to meet criteria of rationality (Davis 2008; Beilharz 2000). For both Gellner and Bauman, modernity’s principal strategy for social transformation was to deploy culture for nation-state building. In ‘Assimilation into Exile: The Jew as a Polish Writer’ (Bauman 1996), included in this volume, Bauman describes this strategy as follows: ‘It encompassed a few generations spanning the stormy, short period needed for modern states to entrench themselves in their historically indispensable, yet transitory, nationalist forms’ (p. 120). Here, Bauman analyses the issue of the congruence between culture and the state through the prism of the rebirth of the Polish state, and the history of Polish–Jewish relations, in the beginning of the twentieth century (see Wagner 2020; Cheyette 2020; J. Bauman 1988). The issue of nationalism was, however, only one aspect of Bauman’s analysis of the modern desire to order the world according to the imperatives of objective rationality. Drawing variously upon the work of Michel Foucault (1977), Sigmund Freud (1962) and Max Horkheimer and Theodor Adorno (2002 [1944]), Bauman focused on the disciplinary and surveilling practices of modern states aimed at the subordination of individuals to a rational order. In his most well-known books of the period (Bauman 1991, 1989, 1987), described by Dennis Smith (1999) as his ‘modern trilogy’, Bauman argued that the modern interpretation of utopia as a blueprint for a perfectly ordered and rational society provided the ideological foundations for the horrors of totalitarian states. In his analysis of the Holocaust, Bauman (1989) showed how the idea of a ‘garden culture’ was realized in Nazi Germany by interpreting Jewish people, along with many other marginalized groups, as so many ‘weeds’ that needed to be dug out and disposed of in order to realize a vision for a perfectly planned and ordered Aryan society.

At the same time as reflecting on the traumas of modernity’s ‘will to order’,16 Bauman (1997b, 1993, 1992a) was ruminating upon the dramatic cultural changes under way in the second half of the twentieth century, which led to the emergence of an entirely new cultural condition: postmodernity.17 Initially enthused by the postmodern promise of transcending modern cultural categories and classifications in a riot of ambivalence and individual choice, over the course of the 1990s Bauman would become gradually disillusioned with a social transformation that seemed to be an apology for moral relativism and hedonistic consumerism. On the one hand, he was hopeful for the new opportunities that emerged for individuals after their (apparent) liberation from the structural and normative determinations of modernity. One of the most significant was a chance to develop autonomous moral responsibility in relation to what he called ‘postmodern ethics’ (Bauman 1995, 1993). On the other hand, he lamented what he saw as a loss of moral engagement with and responsibility for the Other, as postmodern consumerism appeared to be creating a culture of only self-regarding individuals (Bauman 1999c, 1998b, 1997b). In the Polish-language paper ‘Beyond the Limits of Interpretative Anarchy’ (Bauman 1997a), published here in English for the first time, Bauman engages with the fields of hermeneutics and literary theory to demonstrate his view on the postmodern moment: ‘The specifically late modern, or post-modern – and probably without precedent – aspect of the pluralism of today’s world lies in the frail and meagre, shallow and brittle institutional roots of differentiation – and thus the resulting blurring, fluidity and relative short-livedness of the identities associated with different ways of life’ (p. 155).18

Given this antinomy, Bauman ceased to identify with post-modernity and questioned its utility for sociological analysis, finally refuting the analytical grasp of any ‘post-X’ conceptualization for social transformations still unfolding (Bauman and Gane 2004).19 In postmodernity’s wake, as is well known, he preferred to describe our contemporary cultural condition by coining the term “liquid modernity” (Bauman 2000). Bauman used this analytical frame as a heuristic device that deployed the metaphor of ‘liquidity’ to develop further his analyses of society as characterized by constantly accelerating cultural change (Bauman 2011b, 2008c, 2005; Bauman and Leoncini 2018). For example, in ‘The Spectre of Barbarism – Then and Now’ (originally published in French (Bauman 2009), but republished here in English for the first time),20 Bauman writes:

Liquid modern culture has no ‘people’ to ‘cultivate’. It has instead clients to seduce. And unlike its solid modern predecessor, it no longer wishes to work itself, the sooner the better, out of a job by accomplishing that mission and bringing its task to conclusion. Its job now is to render its own survival permanent and infinite – through temporalizing all aspects of life of its former wards, now reborn as clients, and condemning them to eternal inconclusiveness. (p. 197)21

This quote neatly captures Bauman’s view that culture in liquid modernity is a constantly expanding smorgasbord of different norms, practices and beliefs. Across many publications in this ‘liquid’ period, Bauman analysed the ‘mosaic’ character of contemporary identities, and interpreted today’s world as ‘the archipelago of diasporas’ (Bauman 2011b, 2004; Bauman and Mauro 2016).22

What is often missed by those who encounter Bauman only in this later period of his writing – and what we hope to have signalled for the reader here – is the remarkable consistency that endures in his theory of culture across six decades of sociological thinking. Culture, at the same time both Promethean and reactionary, was capable of driving progressive social transformations and imposing order-building categories of ‘us and them’. It enabled the realization of, and the retreat from, cultural pluralism (Bauman 2017, 2016, 2004). Bauman has shown how such factors as the ‘migration panic’ intensifying from the mid-2010s (Bauman 2016), social inequalities (Bauman 2011a) and global economic crises (Bauman and Rovirosa-Madrazo 2010) have each negatively affected attitudes towards ‘cultural diversity’ and ‘cosmopolitan identities’. His last book – posthumously published – was a powerful statement on this very issue, as he described the immanent dangers of a return to the modernist vision of culture in his analysis of ‘retrotopia’ (Bauman 2017). By this, he means to capture the use of nostalgia as a mechanism for coping with the uncertainties of liquid life by seeking refuge in the quest to revive so many ‘imagined communities’ now seen to have been somehow lost along the way.

Throughout his career, Bauman returned time and again to the idea of culture as dialogue, even polylogue. He believed ardently that both interpersonal relations and new political instruments – which he always imagined as needing to be supranational entities – should be founded on this open and inclusive concept. His thoughts on this issue are expressed in a Polish-language paper ‘On Love and Hate … In the Footsteps of Barbara Skarga’23 (Bauman 2015,24 available here in English for the first time). Inspired by Boris Akunin’s (2012) novel Аристономия [Aristonomia], Bauman introduced a new concept: the ‘aretonomic personality’. He derives this term from the Greek words arête (meaning ‘moral excellence’) and nomos (meaning ‘law’ or ‘custom’) in order to describe a set of attitudes and dispositions that include: an awareness of the need to act, reliability, balanced self-assessment, honour, responsibility, and empathy for the Other. Bauman stresses, as he did many times in his post-2000 writings (Bauman and Raud 2015; Bauman and Donskis 2013), those factors that significantly hinder the development of such virtues. The more he concentrated on these obstacles, the more he emphasized the need to counteract them. In somewhat utilitarian liberal terms (Davis 2008), he states in that article: ‘A good society has many attributes, but among them I would grant primary place to ensuring that the greatest possible number of human beings that comprise it would want to be virtuous, and that the greatest possible number is given the opportunity to do so’ (p. 221).

As we hope to have shown, Bauman’s theory of culture has explored a multifarious range of social and political issues, whilst remaining faithful to core ideas and principles across six decades of sociological analysis.25 The most steadfast principle informing his theory of culture is its Gramscian nature, which – to repeat – he called ‘a sharp edge pressed obstinately against what-already-is’ (Tester and Jacobsen 2005: 147).26

ARTISTIC IMAGINATION

As Wolf Lepenies (1992: 1) put it, from its inception as a self-conscious pursuit in the nineteenth century, sociology constituted a ‘third culture’ that ‘has oscillated between a scientific orientation, which has led it to ape the natural sciences, and a hermeneutic attitude, which has shifted the discipline towards the realm of literature’. The sociological and artistic imaginations have been historically intertwined, at once reciprocal and conflicting, complementary and tensional (Davis 2013; Nisbet 1976). This intertwining is especially apparent in the work of Bauman (Jacobsen and Marshman 2008; Tester 2004), who understood sociology itself as inescapably embedded in the tension-laden process of culture. Sociology is not a neutral pursuit at a remove from its object, but is itself a cultural form in which human experience is interpreted and through which sociality is constituted. As Bauman (1992a: 216) put it, sociology is an expression of ‘the exercise of human spirituality, the constant reinterpreting of human activity in the course of activity itself’. It is in this way that sociology has an elective affinity with art.

For our purposes, we identify three principal ways in which Bauman engaged with an artistic imagination. First, he wrote extensively on the relationship between sociology and the arts, especially literature (Bauman and Mazzeo 2016). Second, art and literature serve a heuristic purpose for his sociological imagination, enabling him better to explore and to communicate a range of sociological problems. And third, for Bauman, sociology and art were invaluable in the discovery and opening up of human possibilities for a better life for all. In sum, Bauman shares a great deal with Griselda Pollock’s (2007) view that one cannot conceive of practising art history without the aids of sociology, just as sociology must try to grasp that ungraspable element of the human experience expressed by the objects of art, its affects and imagination. In what follows, we will elaborate upon these three points in reference to those selected writings included in this volume to show the multi-dimensionality of his interest in art, including literature, photography, painting, sculpture, theatre and performance.27

In Culture and Society: Preliminaries, published in Polish, Bauman (1966a: 30) states: ‘a scientist has the best chance to create things that are both essentially new and opening new cognitive perspectives when he/she goes beyond one discipline and thus frees himself from the institutionalized routine of sacrificing invention to methodological conformism’. Bauman was faithful to this approach throughout his career, deriving his ‘way of being’ a sociologist from a conviction that truly understanding the human experience ought not to be constrained by artificially erected barriers between academic disciplines. This crucial lesson was learned from his Polish tutors, Julian Hochfeld and Stanisław Ossowski, for whom he frequently expressed his gratitude. Literature, he was fond of saying, provides a useful model for practising sociological reflection (Bauman and Mazzeo 2016; Bauman et al. 2014; Bauman and Tester 2001: 22–4). In ‘A Few (Erratic) Thoughts on the Morganatic Liaison of Theory and Literature’ (Bauman 2010), published here in English for the first time, Bauman makes reference to Milan Kundera (2006, 1988) in pointing out that it is the novel that is able to capture both the irreducible complexity and ambiguity of the human experience. In a novel, depictions of macro social structures and processes may go hand in hand with intimate psychological portraits of individual characters, infused with philosophical and anthropological sensibilities. As Bauman states: ‘Novel-writing unveils before you the multiplicity of meaning of your world and your being-within-it, in order to give meta-freedom a chance, the only one among countless forms of freedom that you cannot surrender without surrendering your humanity: namely, the freedom of choice between self-fulfilment and self-destruction of warnings/prophecies/predictions’ (p. 211). There is no doubt that Bauman’s way of practising sociology as ‘an ongoing dialogue with human experience’ (Bauman and Tester 2001: 40) was aimed at achieving all these purposes. It is also worth noting that, when asked which books he wished to be marooned with upon a desert island, Bauman chose no canonical work of sociology, but rather selected novels by Georges Perec, Italo Calvino, Robert Musil and Jorge Luis Borges (Bauman and Tester 2001: 23–4).

Bauman also drew insightful comparisons between sociology and photography. This was the field of art that crossed into his personal life, and he spent the early 1980s as a semi-professional photographer. His photographic portraits,28 Yorkshire’s landscapes and the ‘palimpsest’ nature of the urban environment29 were exhibited in galleries. Bauman later reflected that his photography had been an artistic anticipation of his subsequent works on postmodernity: ‘Today, years later, I think that in photography I was looking for what was also in my “academic” reflection, not yet able to express it in words’ (Bauman et al. 2009: 91). Our research in the Papers of Janina and Zygmunt Bauman at the University of Leeds discovered scattered notes and short essays devoted to the relationship between photography and his sociological imagination. We have collated and edited these fragments into a single piece that we have called ‘Thinking Photographically’ in deference to one of his books (Bauman and May 2001). In his introductions to exhibitions and his correspondence with galleries, Bauman elaborates on the history of his engagement with photography, the way in which he perfected his technical skills, and his reflections on masters of the craft (amongst whom he includes Henri Cartier-Bresson, André Kertész and Bill Brandt). Consistent with his belief in the function of sociology, Bauman notes that photography too ought to ‘defamiliarize the familiar’, seeking to reveal the extraordinary in the ordinary, and vice versa. He writes: ‘In our daily bustle, we have rarely time, or strength, or will to stop, to look around, to think. We pass by things giving them no chance to puzzle, baffle or just amuse. Photography may make up for our daily neglect. It may sharpen our eyesight, bring into focus things previously unnoticed, transform our experiences into our knowledge’ (p. 106).

The second way in which the artistic imagination entangles with Bauman’s sociology is that products of the former serve as a heuristic device for the latter. There are numerous examples, especially in his ‘liquid’ writings, where a work of art has inspired a sociological discovery, and where a social process is best described through reference to specific works of art. For example, in a conversation with Izabela Wagner (2020: 341), Bauman offers the following explanation for the genesis of his book Modernity and Ambivalence (Bauman 1991):

I did not think about this book at all. I did not plan it at all. I went to a concert at Harrogate … and Yoyo Ma was playing Beethoven sonatas on the cello. Yoyo Ma is a great virtuoso, but what I thought [at that moment] had nothing to do with the sonatas he performed. I came out of this concert with a clear plan for a book about which I never thought deliberately. Of course, the elements were already in my head, but they connected at that concert.

Modernity and Ambivalence contains many examples from art and literature, chiefly the works of Franz Kafka,30 which are called upon to illustrate changing attitudes towards ambiguity. This issue, one of the major components of Bauman’s sociological imagination (Junge 2008), is also apparent in a 1995 essay ‘Einstein Meets Magritte: Postmodernity Is Born’, published here for the first time.31 Bauman has described René Magritte as ‘the greatest philosopher among painters and the greatest painter among philosophers’ (Bauman et al. 2009: 93), an artist whose works anticipated changes in European culture by foregrounding the contingent nature of understanding and reality. Bauman writes of Magritte’s paintings that

they invite the viewers to question the meaning of any ‘reality’, and force them to see into the precariousness of any existence, normally taken as unproblematic. Each object suggests the possibility of being something else than it is, or finding itself in a different place – and by the same token it reveals the uncertainty, ‘merely possible’ status of all others, even the most familiar and comfortingly ‘natural’ shape or location. (p. 115)

Given what we have learned about Bauman’s theory of culture – that the world we inhabit is but one possibility, and thus (qua Gramsci) can always be other than it is – this affinity with Magritte’s playful undermining of comfortable realities can be seen in a new light.

Bauman explored these ideas further in a paper titled ‘On Art, Death and Postmodernity – and What They Do To Each Other’,32 originally published in a book released by the Nordic Institute for Contemporary Art (Bauman 1998a). Referring to artworks by Piet Mondrian, Alexander Calder, Damien Hirst and Joanna Przybyła, Bauman analyses the way that twentieth-century art appears to struggle with ideas of death and infinity. Echoing his distinction between modes of intellectuals (Bauman 1987), he notes the significant difference between modern and postmodern artists. With regard to the former, he writes: ‘the modern (and particularly the modernist) artists presumed a demand for association with the extratemporal, and through it – with immortality itself. In this one respect at least their art was not revolutionary at all’ (p. 163). Mondrian’s rectangular compositions, whilst in other respects avant-garde and innovative, are seen by Bauman as an exemplar of this modernist strategy. In postmodern artworks, the idea of immortality is simply replaced with the idea of constant movement, contingency and the inevitable finiteness of life. On the one hand, this is an interesting essay on the evolution of styles in art; and, on the other, it illustrates the profound changes taking place within European culture at least since the early twentieth century, especially as related to the themes of transience and duration (Bauman 2011b, 2005, 1992a). The essay neatly captures, therefore, the entanglement of Bauman’s sociological and artistic imaginations.

The third expression of art and sociology in Bauman’s writing is that they both spring from the same well of existential determinants that generate the human-made world. They each relativize the present, pulling apart ‘commonsensical thinking’ (Bauman 1976c) and encouraging the search for alternatives to the status quo in the hope of enriching the world for all. For example, in the Afterword to Liquid Modernity, Bauman (2000: 203) points out what sociologists can learn from poets:

we need to pierce the walls of the obvious and self-evident, of that prevailing ideological fashion of the day whose commonality is taken for the proof of its sense. Demolishing such walls is as much the sociologist’s as the poet’s calling, and for the same reason: the walling-up of possibilities belies human potential while obstructing the disclosure of its bluff.33

Bauman also assigns a significant role to theatre in strengthening humanity’s self-reflexivity, creativity and agency.34 In ‘Actors and Spectators’, written in 2004 and published here for the first time, Bauman outlines four characteristics of theatre that enable it to fulfil this role. First, the stage is ‘an empty space’ where the process of creatio ex nihilo takes place thanks to the agency of actors. Second, theatrical plays reveal, on the one hand, the contingency of reality, and, on the other, its human origin. Third, theatrical events are watched live in all their immediacy, giving insight into the intense nature of social transformations. And fourth, theatrical plays reveal all of our continuous efforts at each and every moment just to construct (and hopefully reconstruct) the human world. ‘Such qualities’, he writes:

make of the theatre a laboratory in which realities of daily life may be scanned and scrutinized at close quarters and in which their inner mechanism may be torn wide open so that the intricate connections nowhere else visible as vividly may be brought into light; and such qualities are special privileges of the theatre nowhere else to be found in such concentration. (pp. 174–5)

In ‘Listening to the Past, Talking to the Past’, first published in a catalogue for the White Cube Gallery in London, Bauman (2008b) again emphasizes the urgent need to go beyond the routines of everyday life in order to question its meaning. He writes:

Occasionally … by design or by default, visiting a gallery brings rewards greater than those routinely bargained for: suddenly, we are confronted with a great work of art, the creation of a great artist … The work of an artist who has managed to give visible and tangible shape to our hopes – and to our suspicion of their futility and our fear of their being dashed. (pp. 180–1)

Mirosław Bałka, the internationally celebrated Polish sculptor, is cited by Bauman (2007) as one such artist.35 For his 2003 exhibition ‘Lebensraum’, held at the Foksal Gallery in Warsaw, Bałka presented two objects in the form of gravestones: one protruded from a window, intended to evoke associations with a trampoline; the second was turned upside down and placed on the ceiling. The ambiguous meaning of these objects was deepened further by their illumination as sources of light. In this way, Bałka engaged the audience in a dialogue on the relationship between the past and the future, life and death, as well as with everyday life and festivities. Bauman later analysed Bałka’s 2009 exhibition, ‘How It Is’, presented at the Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall in London. The famous installation took the form of a 13-metre high and 30-metre long black container, creating total darkness inside. Bauman (2011a: 69) writes of his experience within the installation as follows: ‘When you are sunk in the void of the great unknown, freezing mind and senses, shared humanity is your lifeboat; that warmth of human togetherness is your salvation. This is at any rate what Mirosław Bałka’s oeuvre told me and taught me, and for which I am grateful.’

Bauman not only devoted a great deal of content to his reflections on the mutual dependencies between sociological and artistic imaginations, but also gave many of his writings the form of a ‘blurred genre’ (Geertz 1980) between scientific and artistic discourse.36 On the one hand, the essayistic and conversational style that he developed in his postmodern and liquid modern periods helped to reflect the contingent nature of our contemporary condition. On the other hand, this way of writing also grew out of his literary ambitions, which accompanied him throughout all of his life and are apparent in the selected writings collated here. Bauman’s reflections on art and literature, we might say, are themselves works of art.

SUMMARY

This introduction has synthesized Bauman’s reflections on culture and art with reference to those unknown or lesser-known papers selected for this volume. Bauman defined culture throughout most of his long sociological career not only as a system, or as a repository of values, norms and symbols that differentiate one society from another, but also as a thorn in the side of society. His theory of culture as praxis, coupled with his advocacy for ‘active’ utopias, stressed the continuous – essentially endless – process of striving to reduce the gap between the ‘is’ and the ‘ought’ (Bauman 1976b, 1973a). In so striving, Bauman frequently highlighted the invaluable role of art in relativizing present reality in order to open up new spheres of possibility for social transformation. In this, he shared Kundera’s (1988: 160) belief that art is ‘like Penelope, it undoes each night the tapestry that the theologians, philosophers, and learned men have woven the day before’. We hope that readers of this volume of selected writings will see how some of his more celebrated concepts and ideas, as well as the stylistic features characteristic of his writing about ‘liquid modernity’, were already pregnant within papers published far earlier, including in his Polish-language writing. With great insight, Bauman wrote for over six decades both on theories of culture and on great works of art across a number of different crafts and disciplines. What is more, he interpreted these artworks in the context of dramatic cultural and social transformations that took place within both the twentieth and twenty-first centuries.

To close, we return to Gustav Ichheiser’s simile with which we opened our Introduction, in order to acknowledge that, if all we have achieved here is to offer another new door, perhaps previously hidden from view, through which to enter the vast library of Bauman’s writing, then we hope at least that the pages which now follow will flick a different switch and shine a new light upon a once familiar room.

NOTES

1

For more on this traumatic period for Zygmunt and his family, see J. Bauman (1988) and Wagner (2020).

2

Sketches in the Theory of Culture

(2018) was originally to be released in 1968. Its print run was, however, destroyed by Polish authorities as part of a series of repressions against Bauman during the ‘March events’ (Głuchowski and Polonsky 2009). For almost five decades, the book was considered to be irreversibly lost. But, remarkably, one copy survived in the form of an uncorrected set of proofs, which had been secretly hidden in one of Warsaw’s libraries (see Brzeziński 2018a: viii–x).

3

It is worth noting that, in many respects, this particular understanding of culture resembled Émile Durkheim’s concept of ‘social fact’ (Durkheim 1982), which would be strongly criticized by Bauman in subsequent years (Bauman 1976c).

4

This paper is a shorter version of the first chapter of Bauman’s book

Kultura i spoleczenstwo: preliminaria

[

Culture and Society: Preliminaries

] (1966a).

5

In

Sketches in the Theory of Culture

, Bauman (2018 [1968]: 58) wrote: ‘Culture transforms amorphous chaos into a system of probabilities that simultaneously is predictable and can be manipulated – predictable precisely because it can be manipulated. The chaos of experience transforms into a consistent system of meanings, and the collection of individuals into a social system with a stable structure. Culture is the liquidation of the indeterminacy of the human situation (or, at the very least, its reduction) by eliminating some possibilities for the sake of others.’

6

Bauman stated that it was encountering Gramsci’s

Prison Notebooks

(Gramsci 1971) that enabled him to save the ethical core of Marxism despite the deepening disappointment of the communist regime (Bauman and Tester 2001: 25–6), and that allowed him to change his view on the role of culture too (Tester and Jacobsen 2005: 147–8). Bauman’s essay on Gramsci (Bauman 1963) will appear in English for the first time in a forthcoming volume in this series.

7

Bauman revealed his affinity for Gramsci’s philosophy in an earlier lecture on Camus’s

The Rebel

(1956). Bauman commented on this issue about fifty years later, stating: ‘I suppose it was from Gramsci’s Prison Notebooks which I read a year or two after absorbing Camus’s cogito “I rebel, therefore I am”, that I learned how to rebel armed with sociological tools and how to make sociological vocation into a life of rebellion. Gramsci translated to me Camus’s philosophy of human condition into a philosophy of human practice’ (Bauman 2008a: 233). See also Tester (2002).

8