16,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: John Wiley & Sons

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

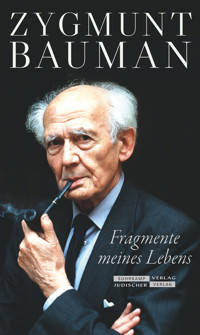

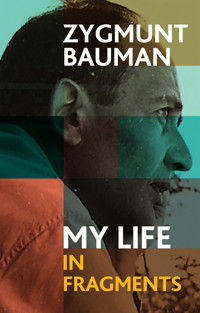

Shortly before his death, Zygmunt Bauman spent several days in conversation with the Swiss journalist Peter Haffner. Out of these conversations emerged this book in which Bauman shows himself to be the pre-eminent social thinker for which he became world renowned, a thinker who never shied away from addressing the great issues of our time and always strove to interrogate received wisdom and common sense, to make the familiar unfamiliar.

As in Bauman’s work more generally, the personal and the political are interwoven in this book. Bauman’s life, which followed the same trajectory as the social and political upheavals of the 20th century, left its trace on his thought. Bauman describes his upbringing in Poland, military service in the Red Army, working for the Polish Secret Service after the war and expulsion from Poland in 1968, providing personal accounts of the historical events on which he brings his social and political insights to bear. His reflections on history, identity, Jewishness, morality, happiness and love are rooted in his own personal journey through the turbulent events of the 20th century to which he bore witness.

These last conversations shed new light on one of the greatest social thinkers of our time, offering a more personal perspective on a man who changed our way of thinking about the modern world.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 210

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Ähnliche

Table of Contents

Title Page

Copyright Page

Editorial Note

Preface

Note

Love and GenderChoosing a partner: why we are losing the capacity to love

Experience and RemembranceFate: how we make the history that makes us

Notes

Jewishness and AmbivalenceAdaptation: why were Jews attracted to communism?

Note

Intellect and CommitmentSociology: why it should not separate objective from personal experience

Notes

Power and IdentityModernity: on the compulsion to be no one, or become someone else

Notes

Society and ResponsibilitySolidarity: why everyone becomes everyone else’s enemy

Notes

Religion and FundamentalismThe end of the world: why it is important to believe in (a non-existent) God

Notes

Utopia and HistoryTime travel: where is ‘the beyond’ today?

Present and FutureHuman waste: who are the witches of modern society?

Notes

Happiness and MoralityThe good life: what does it mean to take off shoes that are too tight?

Notes

Select bibliography

Zygmunt Bauman

Janina Bauman

End User License Agreement

Guide

Cover

Table of Contents

Begin Reading

Pages

iii

iv

vii

viii

ix

x

xi

xii

132

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

133

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

134

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

108

109

110

111

112

113

114

115

116

117

118

119

120

121

122

123

124

125

126

127

128

129

130

131

135

136

137

Making the Familiar Unfamiliar

A Conversation with Peter Haffner

Zygmunt Bauman

Translated by Daniel Steuer

polity

Copyright Page

Copyright © 2017 by Peter Haffner

Translated from the German language: ZYGMUNT BAUMAN, Das Vertraute unvertraut machen. Ein Gespräch mit Peter Haffner. First published in Germany by: Hoffmann & Campe

This English edition © 2020 by Polity Press

The translation of this work was supported by a grant from the Goethe-Institut.

Polity Press

65 Bridge Street

Cambridge CB2 1UR, UK

Polity Press

101 Station Landing

Suite 300

Medford, MA 02155, USA

All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purpose of criticism and review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher.

ISBN-13: 978-1-5095-4230-7

ISBN-13: 978-1-5095-4231-4 (paperback)

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Bauman, Zygmunt, 1925-2017, interviewee. | Haffner, Peter, 1953-interviewer.

Title: Making the familiar unfamiliar : a conversation with Peter Haffner / Zygmunt Bauman ; translated by Daniel Steuer.

Other titles: Vertraute unvertraut machen. English.

Description: Cambridge, UK ; Medford, MA : Polity Press, 2020. | Includes bibliographical references. | Summary: “The last interview of one of the greatest social thinkers of our time”-- Provided by publisher.

Identifiers: LCCN 2020012868 (print) | LCCN 2020012869 (ebook) | ISBN 9781509542307 (hardback) | ISBN 9781509542314 (paperback) | ISBN 9781509542321 (epub)

Subjects: LCSH: Bauman, Zygmunt, 1925-2017--Interviews. | Sociologists--Poland-- Interviews. | Civilization, Modern--20th century. | Sociology--Philosophy.

Classification: LCC HM479.B39 A5 2020 (print) | LCC HM479.B39 (ebook) | DDC 301.092--dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020012868

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020012869

by Fakenham Prepress Solutions, Fakenham, N orfolk NR21 8NL

The publisher has used its best endeavours to ensure that the URLs for external websites referred to in this book are correct and active at the time of going to press. However, the publisher has no responsibility for the websites and can make no guarantee that a site will remain live or that the content is or will remain appropriate.

Every effort has been made to trace all copyright holders, but if any have been overlooked the publisher will be pleased to include any necessary credits in any subsequent reprint or edition.

For further information on Polity, visit our website: politybooks.com

Editorial Note

The conversations with Zygmunt Bauman that form the basis of this book took place on 10 February 2014 and 21–23 April 2016 at his home in Leeds, England. In addition, Bauman provided me with notes containing biographical information and thoughts on various topics, as well as with excerpts from his then forthcoming book Retrotopia, and he asked me to make use of certain passages of these written sources as answers to some of my questions, so that he would not need to repeat himself in conversation. He also asked me to make use, at one point, of his answers to two questions that had been put to him in an interview conducted by Efrain Kristal and Arne De Boever and published under the title ‘Disconnecting Acts’ in the Los Angeles Review of Books of 11/12 November 2014. In total, the passages based on all these written sources amount to about a dozen pages of the text.

My 2014 interview appeared on 4 July 2015 under the title ‘Die Welt, in der wir leben’ [The world we live in] in Das Magazin (the Saturday supplement of Tages-Anzeiger, Basler Zeitung, Berner Zeitung and Der Bund).

Peter Haffner

Preface

When I visited Zygmunt Bauman for the first time, I was astonished by what seemed a contradiction between the person and his work. Arguably the most influential European sociologist, someone whose anger about the state of the world can be felt in his every line, Bauman enchanted me with his wry sense of humour. His charm was disarming, his joie de vivre infectious.

Following his retirement from the University of Leeds in 1990, Zygmunt Bauman had published book after book at an almost alarming pace. The themes of these books stretch from intimacy to globalization, from reality TV to the Holocaust, from consumerism to cyberspace. He has been called the ‘head of the anti-globalization movement’, the ‘leader of the Occupy movement’ and the ‘prophet of postmodernism’. He is read the world over and considered a truly exceptional scholar in the field of the humanities, whose fragmentation into separate, sharply delineated and jealously protected areas of research he ignored with the insatiable curiosity of a Renaissance man. His reflections do not distinguish between the political and the personal. Why we have lost the capacity to love, why we find it hard to make moral judgements: he investigates the social and personal aspects of these questions with the same thoroughness.

It was this epic view of the world that fascinated me when I began to read his books. It is impossible to remain indifferent to what Zygmunt Bauman writes, even if one does not agree with one or other of the points he makes – or, indeed, even if one disagrees with him altogether. Whoever engages with his work comes away viewing the world, and him- or herself, differently. Zygmunt Bauman described his task as that of making the familiar unfamiliar and the unfamiliar familiar. This, he said, is the task of sociology as such.

This task can only be approached by someone who has the whole human being in view and who moves beyond his or her particular discipline and into philosophy, psychology, anthropology and history, art and literature. Zygmunt Bauman is not someone for minute details, statistical analyses and polls, figures, facts or projections. He draws his pictures with a broad brush on a large canvas, formulates claims, introduces new theses into discussions and provokes disputes. In terms of Isaiah Berlin’s famous typology of thinkers and writers – based on the dictum of the Greek poet Archilochos that ‘The fox knows many things, but the hedgehog knows one big thing’ – Zygmunt Bauman is both hedgehog and fox.1 He introduced the concept of ‘liquid modernity’ to describe our present times, wherein all aspects of life – love, friendship, work, leisure, family, community, society, religion, politics and power – are transformed at unprecedented speed. ‘My life is spent recycling information’, he once said. That sounds modest until one appreciates the amount of material involved.

In a time marked by fear and insecurity, when many people are being taken in by the simple solutions offered by populism, critical analysis of the problems and contradictions in society and the world is needed more than ever. Such analysis is an essential precondition if we are to be able to think about alternatives, even if these are not within easy reach. Zygmunt Bauman, erstwhile communist, never stopped believing in the possibility of a better society, despite all the dreams that have failed. His interest was never in the winners, but in the losers, the uprooted and disenfranchised, the growing numbers of the underprivileged – not only poor people of colour in the Global South, but also members of the Western workforce. The fear that the ground that seemed rock solid during the good old post-war years is giving way is today a global phenomenon, and the middle classes are not spared from it. In a climate that asks you to accept the given and to understand the world, following Leibniz, as the best of all possible worlds, Zygmunt Bauman defends the moment of utopia – not as a blueprint for some future castle in the air but as a motivation to improve the conditions under which we live here and now.

Zygmunt Bauman welcomed me to his house in Leeds, England, for four long conversations on his life’s work. The enchanting front garden, with its moss-covered chairs and its table overgrown by shrubs, borders on a busy road, as if to illustrate that it is only through contradiction that things become fully clear. At 90 years of age, Zygmunt Bauman was tall, slim and as lively and perspicacious as ever. He accompanied his deliberations with extensive gesticulation, as if he were a conductor; in order to emphasize a point, he slammed his fist down on his armrest. When talking about the prospect of dying, he did so with the composure of someone who, as a soldier in the Second World War, a Polish Jew, a refugee in Soviet Russia and a victim of the anti-Semitic purge of Poland in 1968, had experienced at first hand the dark side of the ‘liquid modernity’ whose theoretician he had become.

On each occasion, the coffee table was overloaded with croissants and biscuits, canapés and fruit tarts, cookies and crab mousse, accompanied by hot and cold drinks, juices and Polish ‘kompot’. While my host shared his thoughts with me, he also never forgot to remind me to help myself to all the delights that had been set out in front of me.

Zygmunt Bauman talked about life and the attempts to shape it that are consistently thwarted by fate; he spoke also about the effort to remain, amid all this, someone who can look at himself in the mirror. His hope for me, he said, grasping both my hands as he bade me farewell, was that I would live to be as old as him, because every age, despite all its tribulations, has its beauty.

Zygmunt Bauman died on 9 January 2017 at his home in Leeds.

These final conversations with Bauman will, I hope, be taken up and continued by the reader with other people and in other places.

Peter Haffner, January 2017

Note

1

Isaiah Berlin,

The Hedgehog and the Fox: An Essay on Tolstoy’s View of History

(London: Orion Books, 1992), p. 3.

Love and GenderChoosing a partner: why we are losing the capacity to love

Let us begin with the most important thing: love. You say that we are losing the capacity to love. What brings you to that conclusion?

The trend of looking for partners on the internet follows the trend towards internet shopping. I myself do not like to go to shops; most things, such as books, films, clothes, I buy online. If you want a new jacket, the website of the online shop shows you a catalogue. If you are looking for a new partner, the dating website also shows you a catalogue. The pattern of relationships between customer and commodity becomes the pattern of relationships between human beings.

How is this different from earlier times, when you met your future life companion at the village fete or, if you lived in a city, at a ball? There were personal preferences involved in that as well, weren’t there?

For people who are shy, the internet is certainly helpful. They do not have to worry about blushing when they approach a woman. It is easier for them to make a connection; they are less inhibited. But online dating is about attempting to define the partner’s properties in accordance with one’s own desires. The partner is chosen according to hair colour, height, build, chest measurement, age, and their interests, hobbies, preferences and aversions. This is based on the idea that the object of love can be assembled out of a number of measurable physical and social properties. We lose sight of the decisive factor: the human person.

But even if one defines one’s ‘type’ in this way, isn’t it the case that everything changes as soon as one meets the actual person? That person, after all, is much more than the sum of such external properties.

The danger is that the form of human relationships assumes the form of the relationship one has towards the objects of daily use. I do not vow to be faithful to a chair – why should I vow that I shall keep this as my chair until my dying day? If I do not like it any longer, I buy a new one. This is not a conscious process, but we learn to see the world and human beings in this way. What happens when we meet someone who is more attractive? It is like the case of the Barbie doll: once a new version is on the market, the old one is exchanged for it.

You mean, we separate prematurely?

We enter into a relationship because we expect satisfaction from it. If we feel that another person will give us more satisfaction, we end the current relationship and begin a new one. The beginning of a relationship requires an agreement between two people; ending it only takes one person. This means that both partners live in constant fear of being abandoned, of being discarded like a jacket that has fallen out of fashion.

Well, that is part of the nature of any agreement.

Sure. But in earlier times it was almost impossible to break off a relationship, even if it was not satisfying. Divorce was difficult, and alternatives to marriage practically non-existent. You suffered, yet you stayed together.

And why would the freedom to separate be worse than the compulsion to stay together and be unhappy?

You gain something but also lose something. You have more freedom, but you suffer from the fact that your partner also has more freedom. This leads to a life in which relationships and partnerships are formed on the model of hire purchase. Someone who can leave ties behind does not need to make an effort to preserve them. Human beings are only considered valuable as long as they provide satisfaction. This is based on the belief that lasting ties get in the way of the quest for happiness.

And that, as you say in Liquid Love, your book on friendship and relationships, is erroneous.

It is the problem of ‘liquid love’. In turbulent times, you need friends and partners who do not let you down, who are there for you when you need them. The desire for stability is important in life. The 16-billion-dollar valuation for Facebook is based on that need not to be alone. But, at the same time, we dread the commitment of becoming involved with someone and getting tied down. The fear is that of missing out on something. You want a safe harbour, but at the same time you want to have a free hand.

For sixty-one years you were married to Janina Lewinson, who died in 2009. In her memoir, A Dream of Belonging, she writes that, after your first encounter, you never left her side. Each time, you exclaimed ‘what a happy coincidence’ it was that you had to go where she wanted to go! And when she told you that she was pregnant, you danced in the street and kissed her – while wearing your Polish Army captain’s uniform, which caused something of a stir. Even after decades of marriage, Janina writes, you still sent her love letters. What constitutes true love?

When I saw Janina, I knew at once that I did not need to look further. It was love at first sight. Within nine days I had proposed to her. True love is that elusive but overwhelming joy of the ‘I and thou’, being there for one another, becoming one, the joy of making a difference in something that is important not only to you. To be needed, or even perhaps irreplaceable, is an exhilarating feeling. It is difficult to achieve. And it is unattainable if you remain in the solitude of the egotist who is only interested in himself.

Love demands sacrifice, then.

If the nature of love consists in the inclination always to stand by the object of your love, to support it, to encourage and praise it, then a lover must be prepared to put self-interest in second place, behind the loved one – must be prepared to consider his or her own happiness as a side-issue, a side-effect of the happiness of the other. To use the Greek poet Lucian’s words, the beloved is the one to whom one ‘pledges one’s fate’. Contrary to the prevailing wisdom, within a loving relationship, altruism and egotism are not irreconcilable opposites. They unite, amalgamate and finally can no longer be distinguished or separated from each other.

The American writer Colette Dowling dubbed women’s fear of independence the ‘Cinderella complex’. She calls the yearning for security, warmth and being-cared-for a ‘dangerous emotion’ and urges her fellow women not to deprive themselves of their freedom. Where do you disagree with this admonition?

Dowling warned against the impulse to care for others and thus to lose the possibility of jumping, at will, on the latest bandwagon. It is typical of the private utopias of the cowboys and cowgirls of the consumer age that they demand an enormous degree of freedom for themselves. They think the world revolves around them, and the performances they aim for are solo acts. They can never get enough of that.

The Switzerland in which I grew up was not a democracy. Until 1971, women – that is, half of the population – did not have the vote. The principle of equal pay for equal work is still not established, and women are under-represented in boardrooms. Are there not any number of good reasons for women to get rid of their dependencies?

Equal rights in these areas are important. But there are two movements within feminism that must be distinguished. One of them wants to make women indistinguishable from men. Women are meant to serve in the army and go to war, and they ask: why are we not allowed to shoot other people dead when men are permitted to do so? The other movement wants to make the world more feminine. The military, politics, everything that has been created, was created by men for men. A lot of what is wrong today is the result of that fact. Equal rights – of course. But should women simply pursue the values that have been created by men?

Is this not a decision that, in a democracy, must be left to women themselves?

Well, in any case, I do not expect that the world would be very much better if women functioned the same way that men did and do.

In the early years of your marriage you were a house-husband avant la lettre. You did the cooking and looked after two little children while your wife worked in an office. That was rather unusual in the Poland of those days, wasn’t it?

It wasn’t all that unusual, even though Poland was a conservative country. In that respect, the communists were revolutionary, because they considered men and women to be equal as workers. The novelty about communist Poland was that a large number of women worked in factories or offices. You needed two incomes at the time in order to provide for a family.

That led to a change in the position of women and thus to a change in relations between the sexes.

It was an interesting phenomenon. The women tried to understand themselves as economic agents. In the old Poland, the husband had been the sole provider, responsible for the whole family. In fact, however, women made an enormous contribution to the economy. Women took care of a lot of the work, but it did not count and was not translated into economic value. Just to give an example, when the first laundrette opened in Poland, making it possible to have someone else wash one’s dirty laundry, this saved people an enormous amount of time. I remember that my mother spent two days a week doing the washing, drying and ironing for the whole family. But women were reluctant to make use of the new service. Journalists wanted to know why. They told the women that having someone else do their laundry was much cheaper than them doing it themselves. ‘How come?’, the women exclaimed, presenting the journalists with a calculation showing that the overall cost of washing powder, soap and fuel for the stoves used for heating up the water was lower than that of having everything washed at the laundrette. But they had not included their labour in the calculation. The idea that their labour also had its price did not occur to them.

That was no different in the West.

It took several years before society got used to the fact that the household work done by women also had a price tag attached. But by the time people had become aware of this, there were soon only very few families with traditional housewives.

In her memoirs, Janina writes that you took care of everything when she fell ill with puerperal fever after the birth of your twin daughters. You got up at night when the babies, Lydia and Irena, were crying, gave them a bottle; you changed nappies, washed them in the morning and hung them up to dry in the backyard. You took Anna, your oldest daughter, to the nursery, fetched her again. You waited in the long queues in front of the shops when doing the errands. And you did all this while also fulfilling your duties as a lecturer, supervising your students, writing your own dissertation and attending political meetings. How did you manage to do that?

As was the norm in academic life back then, I was more or less able to dispose of my time as I chose. I went to the university when I had to, to give a seminar or a lecture. Apart from that, I was a free man. I could stay in my office or go home, go for walks, dance, do whatever I liked. Janina, by comparison, worked in an office. She reviewed screenplays; she was a translator and editor at the Polish state-run film company. There was a time clock there, and it was thus clear that I had to be there for the children and the housework whenever she was at the office or ill. That did not lead to any tension; it was taken for granted.

Janina and you grew up in different circumstances. She came from a wealthy family of physicians; in your family, money was always tight. And Janina was probably not prepared for being a housewife, for cooking, cleaning, doing all the work that in her parents’ home had been done by servants.