22,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: John Wiley & Sons

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

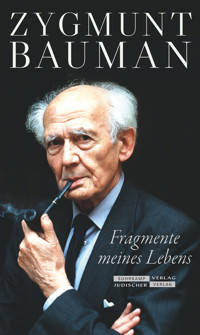

Zygmunt Bauman was one of the great social thinkers of our time: inventor of the idea of liquid modernity, he transformed our way of thinking about the social conditions shaping our lives today. His own life was shaped by the great social forces that scarred the second half of the twentieth century – war, communism, antisemitism, forced migration. His work bears the traces of an outsider who knew all too well the enormous impact that social and political forces can have on personal lives.

Bauman never wrote a full biography, but he wrote extended letters to his daughters in which he recounted the details of his life – his childhood and schooling; his experiences during the war and its aftermath; his forced emigration from Poland in 1968 and his subsequent life in exile, first in Israel and then in the UK, where he eventually settled at the University of Leeds. This book makes available for the first time these fragments of a life recounted, woven into a compelling autobiographical narrative that is laced with the broader reflections of a master thinker on some of the great issues of our time: identity, antisemitism and totalitarianism.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 398

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Ähnliche

CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Introduction

Notes

1 The Story of Just Another Life?

3 January 1997

4 January

5 January

6 January

9 January

11 January

12 January

16 January

28 January

30 January

31 January

7 February

Notes

2 Where I Came From

Notes

3 The Fate of a Refugee and Soldier

Notes

4 Maturation

Notes

5 Who Am I?

Notes

6 Before Dusk Falls

Notes

7 Looking Back – for the Last Time

Notes

Appendix: Source Material

End User License Agreement

Guide

Cover

Table of Contents

Title Page

Copyright

Introduction

Begin Reading

Appendix: Source Material

End User License Agreement

Pages

iii

iv

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

108

109

110

111

112

113

114

115

116

117

118

119

120

121

122

123

124

125

126

127

128

129

130

131

132

133

134

135

136

137

138

139

140

141

142

143

144

145

146

147

148

149

150

151

152

153

154

155

156

157

158

159

160

161

162

163

164

165

166

167

168

169

170

171

172

173

174

175

176

177

178

179

180

181

182

183

184

185

186

187

188

189

190

191

192

193

194

195

196

197

198

233

My Life in Fragments

Zygmunt Bauman

Edited by Izabela Wagner

With translations by Katarzyna Bartoszyńska

polity

Copyright © Zygmunt Bauman 2023

Introduction © Izabela Wagner 2023

English translations of material translated from Polish © Polity Press 2023

The right of Zygmunt Bauman to be identified as Author of this Work has been asserted in accordance with the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

First published in 2023 by Polity Press

Polity Press65 Bridge StreetCambridge CB2 1UR, UK

Polity Press111 River StreetHoboken, NJ 07030, USA

All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purpose of criticism and review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher.

ISBN-13: 978-1-5095-5131-6

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2023934250

The publisher has used its best endeavours to ensure that the URLs for external websites referred to in this book are correct and active at the time of going to press. However, the publisher has no responsibility for the websites and can make no guarantee that a site will remain live or that the content is or will remain appropriate.

Every effort has been made to trace all copyright holders, but if any have been overlooked the publisher will be pleased to include any necessary credits in any subsequent reprint or edition.

For further information on Polity, visit our website:politybooks.com

Introduction

Izabela Wagner

My Life in Fragments is a book that was created as a patchwork – from very different pieces. Not only, as the title suggests, because Zygmunt Bauman is telling stories about his life in a nonlinear way. This is not his autobiography, even if some chapters are autobiographical. This volume is composed of different texts written by Zygmunt Bauman across a span of thirty years. The lengthy diary entries and stories were written in Polish and English – two languages that Bauman mastered and used in both his work and his private life. The status of these pieces also varies. While one part, devoted to his childhood and teenage years, is private, written for his daughters and grandchildren, another part is public. Some pages were never published, while other pages were published in Polish as chapters in a book or press articles several years ago.1 Constructing a book from such varied writings was highly challenging.

The core of the book is Bauman’s typescript dated 1987, which contains fifty-four pages, with the first title page as follows:

The Poles, The Jews, and I

An Investigation into Whatever Made Me

What I am

The Memory of My father

Entrusted to the Memory

of My Children –

sixty two years and three months

after my birth.

‘Feb. 1987’ was added in pencil by a family member and was the result of an arithmetic calculation carried out much later: 19 November 1925 (the date of Bauman’s birth) plus 62 years and 3 months. Except that the author of the note erred in the calculation, and the year in which the text was being composed was in fact 1988. This text was written for the family. There are no references; it contains private family secrets and has never before been published in its entirety. Now, his family has decided to share with his readers this unique piece of Bauman scholarship. I read it for the first time in mid-December 2017, when, almost a year after Zygmunt Bauman passed away, the family sent me the text as a PDF file, along with the permission for quotations to be used in Bauman: A Biography – the book I was then working on, published over two years later. I am grateful to Bauman’s family for their trust, and I am relieved now – thanks to their decision – that this precious text is available to all English-speaking readers. I confess that it was challenging to choose which parts of the manuscript to quote in my book, since the entire account is fascinating.

Not only was the story captivating, but it was the first time that Bauman wrote about his life and focused on it. In these pages, it is not an intellectual speaking about the world, but a person making a confession in a way typical for people in the later stages of their lives. People tell their life stories to preserve them from oblivion. The purpose here is intergenerational transmission within a family, and the preservation of family history. I felt privileged, and tried to include in my book Bauman: A Biography as many quotations as possible. In the biography, Bauman’s voice was intertwined with analysis of the historical and political contexts, which helped with understanding his situation and life choices. In this volume, his account is not cut but completed by his other writings, which focus on his life experiences. ‘The Poles, The Jews, and I’ is the only material published in this book written in English. This may be surprising if we consider that all these souvenirs concern childhood, youth and family history, and that his childhood and youth were spent in contexts where Polish was spoken. Then Bauman reflects on his identity (ethnic identity), asking himself the question: why write in English? And he responds convincingly – indeed, this is the main topic of his reflection.

The second part of the material included in this book is from twenty-four pages written in 1997, entitled ‘Historia jeszcze jednego życia?’ (‘The story of just another life?’), and is in the form of a diary. Thanks to the dates clearly stated each time Bauman started a new note, we can conclude that keeping a journal was not his daily habit or routine. As his daughters remember, it was a typical New Year’s resolution, which was abandoned after a couple of weeks. This diary started probably on 1 or 2 January,2 and ended on 7 February in the same year.

The third, lengthiest part of the text was edited at the end of his life and contained 136 pages, starting with a chapter entitled ‘Dlaczego nie powinienem tego pisać’ (‘Why I should not write this’). This text, written in Polish, has the form of a manuscript almost ready for the process of publication. The same family stories were told in the English typescript; however, the text contains some changes, mainly developments of the same topics. Bauman here provides more details in order better to explain events that are described in a different way in the other available sources.3 We should remember that Bauman was a scapegoat for Polish extreme-right and nationalist movements. He was accused of being an active supporter of communism, which is virtually a sin in contemporary Poland. It was often mentioned that Bauman never ‘explained himself’ about his participation in the construction of communism. It was expected that he would present an apology for what he supposedly did (he was never charged with any crime). He was the target of a ‘witch hunt’, an extreme example of the treatment left-leaning individuals with a communist past could experience in Poland after 1989. This Polish text is partially a response to these attacks, and Bauman devotes ample space to his political engagements and the recent political situation in Poland. The text from the English manuscript in chapters 2 and 3 is written in a different style. Another type of narrative appears when Bauman is speaking about his identity – the core question of his reflection being ‘Who am I?’ In English, Bauman is more direct, using the form ‘I’ when speaking about being a Jew – ‘I am a Polish Jew.’ In Polish, he is more distanced and becomes part of a collective – he is a part of a group. The English text is more private, which is only to be expected as his audience was his family; but also, in English, he seems to feel safe, as though the Polish language cannot provide the same security when confronting antisemitism.

The three sources that make up this book were written over the span of thirty years. It is not surprising that Bauman started writing about his parents and childhood in 1987. A couple of months before he wrote the first pages of his memoirs, his wife Janina Bauman published her autobiographical book Winter in the Morning, which became a significant turning point in his life.4 That book – partially based on Janina’s diary, which was miraculously preserved during and after World War II – recalls the life of a young teenage girl in the Warsaw Ghetto. Janina Bauman is telling her story, a story of a Holocaust survivor. From this substantial testimony for Holocaust studies, Bauman’s family learned about Janina’s tragic past. Zygmunt’s reaction to that painful and astonishing history, of which he was previously unaware, was to write. He did it in two ways: academically – he published in 1989 his groundbreaking book Modernity and the Holocaust; and privately. All of that deeply personal writing appears in this volume.5

While the long Polish text contains similar material to that in the English manuscript, the latter took priority in assembling this text. Because of the style of writing (direct and personal, which is unusual in Bauman’s work) and the fact that it was the original,6 it seemed more appropriate to keep this English version and complete it, if needed, with fragments of text translated from the Polish. However, the composition of the successive chapters, their titles and structure mainly follow Bauman’s organization, which can be seen in the third text (the long Polish manuscript). While this book is made up of different texts that were written at different times in both Polish and English, and that overlap in various ways, the material has been integrated here into a single coherent text of seven chapters, following the logic that was evident in the material itself.

The book starts with a general reflection on autobiographical writing. Here, Bauman’s readers will be at home, finding an unpublished text written in a typical Bauman style and discussing with writers and intellectuals the subjectivity of memory and the influence of time on the content of stored memories. Bauman is guiding his readers through the fascinating labyrinth of the mystery of human memory, the interpretation of facts, and the complexity of a life recalled later – all this contributing to the construction of the author’s persona. After this sketch of the theoretical frame, we jump into Bauman’s life – his family history, interwar Poland and, despite antisemitic discrimination, quite a happy childhood. The third chapter is the story of the war years – Bauman is a teenage refugee, then a soldier liberating his homeland from the Nazi occupation. These prewar and wartime chapters are full of personal details and almost without references to other authors. It is Bauman’s life, as he remembers it now (in 1987). The chapter entitled ‘Maturation’ is different, as the author focuses on the beginning of his leftist engagement and discusses the post-war period as an intellectual. The voice of a former refugee and soldier is replaced by the voice of the sociologist Zygmunt Bauman, who, with mastery, is conversing about human choices with many authors – historians, sociologists, writers and poets. This is a very important chapter that directly responds to the claims of Bauman’s opponents in Poland, who complained about his silence regarding his political engagement and post-war experiences.

The following chapter is devoted to a reflection on Bauman’s ethnic identity. It is an important piece that may join today’s other classical reflections on Polish-Jewish and/or Jewish-Polish identities. His non-contested Jewishness meets contested Polishness. Bauman refuses a simple categorization (into ‘tribes’) and the imposition of choice, claiming the rights of each individual to choose their way of belonging and living on our planet. This powerful chapter will surely be discussed mainly in light of current political changes and the revival of nationalistic, simplistic, black-and-white perceptions of the world. After this personal reflection, in the sixth chapter, Bauman returns to his role as a public intellectual.

Focusing on Polish political changes, this chapter was written in Polish for a Polish audience; however, thanks to the notes, the text is accessible to readers unfamiliar with Polish politics. Despite being closely connected to current affairs (the first decade of the twenty-first century), this chapter contains a precious reflection on authoritarianism and dictatorships. These phenomena destroy fragile democracy not only in Poland but also elsewhere in the world. Unfortunately, this topic, so dramatically experienced and deeply researched by Bauman, is becoming more and more part of life because of the developments that we are witnessing now. The last chapter concludes the book beautifully with Bauman’s acceptance of his life’s experiences. Bauman is making peace with his past and a difficult history (not particularly because of his individual experiences, but because of history itself) and takes full responsibility for his choices. This is the last message in this posthumous book, which, I hope, will be no different from the one that Zygmunt Bauman would have published.

Zygmunt Bauman’s Polish texts are incredibly challenging, even though his erudition and language skills are outstanding. He was the best student at the best school in Poznań, and also in other schools that he attended. A voracious and ‘addicted’ reader throughout his life, he had an extraordinary memory with the capacity to incorporate into his writing many different vocabularies (specific terms from medicine, chemistry, biology and physics), along with classical – but also unusual – references to poetry, movies, theatre and literature, not only from the world of Polish culture but also from other languages and cultures. He added to this treasure many current, popular expressions, or even the occasional vernacular or slang term – not always from the present day, sometimes from the nineteenth century. This is why translation and incorporation into English and Western culture were very challenging – an impossible task for one person, so successive collaboration was needed. The collective effort started with Katarzyna Bartoszyńska, who did the first translation, including of citations from Polish, derived from books which were not published in English. Then, Paulina Bożek helped me to preserve Bauman’s wealth of language. In the final stage, Leigh Mueller brought the translated text as close as possible to the English style of Bauman’s writing. Then, the last significant corrections were made by Anna Sfard. We focused on preserving Bauman’s extremely erudite way of expressing himself, with some elements of humour and hidden and double meanings. It was a long process in which it felt like I was discussing and discovering Bauman all over again. After many years of study devoted to his life’s trajectory, I was back into a direct conversation, which invited me one more time to reflect on our human condition today.

The personal character of the writings was also the source of additional work, which was needed to locate missing references. Bauman included some notes, but not many, and these are preceded below by his initials, ‘ZB’. This is also the case for notes added by Katarzyna, the translator (preceded by ‘TN’). The notes without attribution are mine. In this challenging task (for example, citing poems published in a Polish journal seventy years ago, by an excellent poet who, unfortunately, is not widely known), I was helped by my friends and colleagues, for whose contribution I am most grateful. I wish to thank, for their invaluable responses: Natalia Aleksiun, Alicja Badowska-Wójcik, Izabela Barry, Michael Barry, Agnieszka Bielska, Dariusz Brzeziński, Beata Chmiel, Mariusz Finkielsztein, Andrzej Franaszek, Jan Tomasz Gross, Irena Grudzińska-Gross, Roma Kolarzowa, Adam Kopciowski, Katarzyna Kwiatkowska-Moskalewicz, Joanna Beata Michlic, Jack Palmer, Krzysztof Persak, Adam Puławski, Michał Rusinek, Leszek Szaruga and Natalia Woroszylska.

Last, but not least, I would like to express my gratitude again to the Bauman family for their willingness to allow publication of the private manuscript and for giving me the chance to work on this exceptional book. I also wish to thank John Thompson, who not only supported me in this process, but took an active part in the organization and design of the book as well. Thanks to everyone who collaborated on this project; I hope we can meet the challenge. I am convinced this volume will contribute to the re-reading and better understanding of Bauman’s work. It is one more step, after Bauman: A Biography, that will bring Bauman closer to his readers. They have a chance to do what was only partly possible until now: to enter his private life, and share his most personal memories and reflections.

Enjoy this fascinating journey!

Notes

1.

Z. Bauman, R. Kubicki and A. Zeidler-Janiszewska,

Humanista w ponowoczesnym świecie – rozmowy o sztuce życia, nauce, życiu sztuki i innych sprawach

(‘A Humanist in the Postmodern World – Conversations on the Art of Life, Science, the Life of Art and Other Matters’), Poznań: Zyska i s-ka, 1997.

2.

The first entry is not dated but the second note was written on 3 January.

3.

The analysis of the differences between the English and Polish versions of his memories deserves more space and will be the subject of an academic paper.

4.

J. Bauman,

Winter in the Morning: A Young Girl’s Life in the Warsaw Ghetto and Beyond 1939–1945.

Bath: Chivers Press, 1986–7.

5.

For more about the influence of Janina Bauman’s book on Zygmunt Bauman’s work and life, see I. Wagner,

Bauman: A Biography

, Cambridge: Polity, 2020; and I. Wagner, ‘Janina and Zygmunt Bauman: a case study of inspiring collaboration’ in

Revisiting Modernity and the Holocaust: Heritage, Dilemmas, Extensions

, ed. J. Palmer and D. Brzeziński, Routledge, 2022, pp. 156–76.

6.

Janina Bauman beautifully translated this text into Polish – the text is conserved in the Papers of Janina and Zygmunt Bauman in the Special Collections at the University of Leeds.

1The Story of Just Another Life?

Who needs it? And what for? One life is like another, one life is not like another …

You look at someone else’s life – at the story of someone else’s life – as you do into a mirror, but only in order to confirm that your pimples are on a different side of the nose from theirs; that there are more, or fewer, wrinkles under your eyes; that the eyebrows are thicker, and the nostrils hairier … In order to uncover, in the clutter of the features, the logic of the face. Or also perhaps the comfort – if, in those features as in your own, no order is to be found. Is this what the stories of a life are needed for?

To narrate a life; to turn a life into a story; to become convinced that it is possible to do this, and therefore to calm fears all the more terrible because they are so rarely spoken – that your life cannot be told, because there is no main thread, even if there are many twists. What can be told ‘has a point’. As much of a point as plots do. Stringing the beads onto a necklace, making coloured shards into a mosaic; the necklace is the point of the beads, the mosaic the point of the shards. This point is a supplement, an addition – that ‘something more’ that the beads acquire when you string them all together. But, first, they are smooth balls and uneven blocks, fragments large and small, unwieldy, strangely shaped. Necklaces and mosaics come later. We live twice. Once, breaking and flattening; the second time, gathering the pieces and arranging them in patterns. First, living; second, narrating the experience. This second life, for whatever reason, seems more important than the first. It’s only in the second one that the ‘point’1 appears.

The first is only the preface to the second, the transportation of bricks to the construction site. It is a strange construction – life. First you bring the bricks and gather them into a pile; only later, when you’ve run out of bricks, when the kilns have gone dark and the brickmakers are approaching bankruptcy, do you sit down at the drawing board to sketch out an architectural plan. The promotion from builder to architect comes after you have finished construction – but, in distinction from the law, retro agit … Is it for this promotion that you tell your life story?

The first life passes. The second – the narrated one – lasts; and that existence is a ticket to eternity. In the first one, you can’t redo anything; in the second – everything. Eternity is an extension of existence (this is why it is easier to imagine eternity than nothingness; one doesn’t have the experience that could serve as the point of departure, to say about nothingness: ‘the same, only more’). In every experience, there is something: the subject experiencing. Nothingness would have to be the absence of the subject. Non-existence carries the stigma of absurdity; there is nothing absurd in eternity – eternal being has a whiff of the empirical. And in eternity, anything can happen, everything can happen an infinite number of times – everything can be experienced many times and in infinitely many ways. In eternity, nothing ever ends, and certainly nothing ever ends irrevocably. In eternity, there are no foolproof locks, and you can enter every river twice. This is probably why we long for existence. Existence as the one more chance, the chance to reclaim lost chances. A repeated experience – this time knowing how it will turn out. A happy ending instead of a tragedy. Prudence instead of naivety, wisdom instead of stupidity. ‘This or that could have turned out entirely different, if only …’ But that which could have been only becomes apparent when it is no longer possible. Possibilities that are still open give you a headache; those that are foreclosed – a guilty conscience.

Narrating life as a compensation for the life you lived. This is probably what leads to the dream of immortality. Immortality tempts you with the opportunity to tell everything anew – telling it anew again, as many times as needed, until nothing has to be compensated for. Immortality allows you to redeem everything that needs redemption (this cannot be done in a less-than-infinite time). Is it in hopes of a second chance that you tell your life story?

Kundera wrote of exile that it is a state of alienation. Not from the country you have arrived in – that country, on the contrary, you tame by being tamed by it: what is distant today becomes close tomorrow; the foreign, domestic. In exile, you are alienated from the country that you have abandoned: ‘That, which was familiar, by degrees becomes strange.’ ‘Only returning to the native land after a long absence can reveal the substantial strangeness of the world and of existence.’2 But all of life is an exile: exile out of every present moment, from every ‘now’, from every ‘here’. Life is a journey from the familiar to the strange. Its ‘substantial strangeness’ is revealed by the world in every passing moment, immediately after the movement which cannot be retreated from, and the moves in the game of life cannot be taken back. The futile hope for the persistence of familiarity is sparked by the past imperfect – but, after a second, the past moment mercilessly unmasks the ‘substantial strangeness’ of existence. It is hard not to notice this strange, stubborn, unfavourable, hostile inertia of the world. With the passing of time, you speak ever more in the past tense, ever less in the past imperfect, and the future imperfect disappears practically without a trace. Is it possible to restore that which has been alienated, to make it familiar? You can try – by telling your life story …

The subject of the story is not the old, once free but now ossified, movements – but the memories of them. In this second remembered life of theirs, one can mark out a boundary line that separates possibility from being; can restore, in this way, the present of those moments of ‘now’ (‘now’ is characterized by the fact that in it the boundary between what could be and what irreversibly is cannot be seen – the first time because you do not notice it, and the second because you eliminate it). In the first life, you trespassed this boundary line unknowingly, and in the second, you can cross back and forth repeatedly. It is like throwing hardened events into a crucible, where they become soft again, susceptible to moulding, obedient to a newly wise wisdom. Narrating one’s life is the same as going to war with alienation, as boldly proclaiming that exile never happened. It is the same as seeking the recovery of time. Is that why you tell your life story? And is it a confirmation of the delusion that the goal we seek can be reached in stories of other people’s lives?

3 January 1997

This was an introduction to something I wasn’t sure would ever exist. Even a few days ago, I did not know that this introduction would come into being. Even today, I have no idea what will come after, as, against my habits as a writer, this time I am starting without the slightest idea of what to do next. I have no plan beyond the desire to sit, day by day, in my usual habit from 6 a.m. to noon, in front of the keyboard and screen of an obsolete – by today’s standard – Amstrad,3 counting on each new sentence to summon forth another one …

It is all because of the New Year … I am a superstitious person – that is, I have my favourite superstitions, matters in which I like to be superstitious; superstition is the best way I know of to have some ersatz control over one’s own fate, so it is worthwhile playing Blindman’s Bluff with it: so I try to organize the New Year period in accordance with the shape that I hope that the coming year will take, and then treat the results of my efforts as an omen. Thus, it was necessary to take as an omen the fact that, this time, my plans came to nothing, and instead I found myself confronted with ‘the thing itself’ – that is, fate. A blizzard prevented friends from dropping in for a glass of champagne on their way to a New Year’s party; the snowdrifts it left behind made impossible the arrival of a few kind hearts – those friends helpless now, and doomed to loneliness and no New Year’s chat; a final phone call before midnight brought news of which it can only be said that it was a bolt out of a blue sky or a downpour on a sunny day. New Year’s Day was thus preceded and followed in the same style, passed in the company of two ladies, by all measures worthy of respect and kindness, but of the category of those who ask questions only to have the opportunity to provide the most lengthy answer to them; ladies who, for reasons entirely understandable and not at all exclusive to them (a lack of regular listeners), did not even trouble themselves this time to ask questions. It is hard to be surprised that the New Year did not leave me feeling optimistic. Instead of the annual ‘May it continue this way!’, it informed me that ‘Things cannot go on like this.’ Something must be done. Something must change. It must be otherwise – but how?

The New Year period, for both rational reasons and the superstitious ones that sprout from them, and the predictions one seeks in them, is also an occasion for summarizing and planning. At such a time, one does not make discoveries and rarely has new ideas. It is, rather, the thoughts that have long been tumbling around in one’s mind – or in that secret, no more clearly defined seat of the subconscious – that drift to the surface decked out in words, and take on clear contours. That is certainly what happened this New Year. Except that, at the surface, two thoughts collided – both long present, but so far repressed; and their meeting led to something like a chemical reaction, as if two gaseous substances, colourless and volatile, merged into a solid body, hard, with loud colours, but undissolvable …

4 January

This first thought is about death. Not so much about it being close (though it came closer by a ferocious leap in the moment when I outlived my father: he died on the day of his seventieth birthday), as about how to behave in regard to it, and how to arrange things, so as to act in the way that was decided upon. I know that I am not lying to myself when I tell myself that what is important is not how long one lives, but, rather, to live out the time one has in a dignified and meaningful way. The nightmare is not so much death, as the kind of meaningless vegetation that modern medicine inserts between the moment when a person was supposed to die and the moment when doctors decide that they are allowed to die – between human death and clinical death. With such a set of options, a sensible person should choose to ‘leave at their own demand’. The catch is that, alongside good sense, one also needs a stroke of luck. I love life: the people among whom that life is spent, and that which my – conscious, active – presence contributes or can contribute; I do not want to leave life prematurely. But how to grasp that moment in which ‘prematurely’ is transformed into ‘too late’? And, once grasped, how to admit to oneself that it has been grasped, or even to enter into the Pascalian wager with oneself and stick to it? Koestler succeeded in doing it, Kotarbiński did not.4 So the best solution is not one that can really be counted on. There remains the second: not to cooperate with doctors, and, especially, not to help them – and certainly not to invite them – to demonstrate the artistry that they strive to perfect: cultivating cabbages. When a so-called ‘fatal illness’ arrives (the very concept is already the exanthema of medical technology: the point is mainly to conceal the fact that the only truly fatal, incurable illness is life), not to oppose it – if anything, to give it a leg up. For a long time now, I have had various disorders, some of which, according to textbooks, testify to something ‘serious’ – but as long as they do not disturb my work or interrupt my everyday routine, it is better not to confess to doctors about them.

But, if so, then it is necessary to reckon with the finitude of time, which we have known about since birth but which, for the longest part of our life, we do not have to consider, because the tasks we set ourselves are cut to such a measure as to fit comfortably within a ‘foreseeable phase of life’. Nothing in a life so organized will prepare us for turning the abstraction that is human mortality into a practical problem – we learn to select among matters to be dealt with, but this selection is free from the pungent sense of an ultimate decision: it is not so much that we resign, as that we delay. If not today, tomorrow … Tomorrow seems like an eternity, because every task that demands our efforts can be fitted into some number of tomorrows and day-after-tomorrows. But what happens when we start to see the bottom of the bag of tomorrows? Then it is an entirely different kind of ‘selection’, and there was no time to learn that other kind. When the doctors told Stanisław Ossowski5 that he had a few months left to live, this worldly man, whose gaze could penetrate to the depths of fate and bravely face his opponents, confessed to a hitherto unknown feeling of loss and powerlessness. ‘I had always considered which issues to take up first, which later, what to write first, what later, which books to read right away, which to set aside for later … And now suddenly there is no more later, instead of “later” there is never.’6 The experience of even the most reasoned choices between ‘now’ and ‘later’ does not produce any lessons in how to choose between ‘now’ and ‘never’.

But at some age – such as mine – a thinking person should not wait for a reminder from doctors to begin to live as if confronted by the choice between ‘now’ and ‘never’. It is necessary to get rid of the comforting belief that what is put off will not escape, and if life without it seems like a nightmare, at least break the nightmare’s fangs and clip its claws by striving to arrange your days so that ‘delaying’ weighs as little on your conscience as possible: in other words, only do things that are important, the most important.

At this point, the first thought has ripened enough to encounter the second thought …

I read yesterday in the third volume of Maria Dąbrowska’s diaries a sentence that glimmers in its sagacity, and faced with which the fat volumes on the topic by respected sociologists are dwarfed, seem worthy of laughter and a contemptuous shrug of the shoulders. (Did she just blurt it out? Did she realize the power of it?) On the occasion of a visit to Nieborów in the company of intellectuals ‘of a Jewish origin’7 in a hot, pre-October period,8 Dąbrowska notes that ‘justice demands that we acknowledge, that if there is any sort of free and creative thought circulating, it is among them. In this moment they are the bravest “destroyers of police-enforced order”. Even in social conversations they are more interesting than nativeborn Poles … Personally, as a writer, I must say, qu’ils ne m’embêtent jamais comme nos gens9.’10 And just after comes this major sentence: ‘With all of this, it irritates people; as if someone, who is not entirely us, wanted in all ways to live our lives instead of us.’11 Yes, that is what it is all about, here is the point – the rest is ideological beautification/justification. Not to be entirely one of us is not, in and of itself, a sin; wanting to live instead of us – also isn’t. The combination creates a combustible mixture.

Dąbrowska was better ‘positioned’ than many others to perceive this. Her allosemitism,12 typical of the gentry,13 granted Jews a prominent and uncontested place: Jewish tailors, peddlers, tenant farmers. In the context of such otherness, Jews were like everyone else. You can be an excellent tenant farmer just like you can be an excellent overseer or gardener; and you can be a good person even as a tenant farmer, and a forester – everyone in their own way. It is the Jew who deviates from their role who causes concern and outrage: not wanting to ‘live for himself’, at the same time he wants to ‘live instead of us’ – a life that is reserved for us. And what if he also succeeds in these ignoble efforts? If he is ‘excellent’ in the role that we are meant to play, but that we somehow are not eager for? Rubbing salt into the open wounds of the conscience …

The cursed vicious circle: that ‘our people’ cannot not feel as they feel, and ‘ethnics’ cannot not behave as they behave. On the one hand: to the same degree that the social position of Dąbrowska sharpened her gaze, the social position of ‘ethnics’ makes them natural ‘destroyers of order’, because it is to them that the now poisonous fumes of the rot reach, when others are still breathing an air that is admittedly stale, but still breathable. And, on the other hand: their room for manoeuvre is smaller than that of others. If they refuse to do what the nation in a state of war with the unwanted order considers proper, they will be accused of their foreignness or natural tendency to treachery; if they do the thing, they will have to try harder than others, because what is acceptable for a voivode …14 And if they succeed and are worthy of reward – it will be said that it was stolen.

And the second feeling, which it became increasingly harder for me to silence, and which it was increasingly harder for me to live with, was a feeling of disillusionment and discouragement, towards that ‘academic discipline’ which, for a great majority of my life – with enthusiasm or gritted teeth, but always as much as I was able to honestly afford – I served.

5 January

Sociology; ‘social science’; when did the hope that was its midwife transform into deceit? Did it become a deceit that was consciously practised, and if so, when?

A promise of certainty is deceit. A promise never fulfilled and with no chance of being fulfilled, but an ever-renewing, galvanizing illusion, which hinders humans from looking into the eyes of that which is the most human in their fates. The promise of exorcizing magic forces from human life, as was done for the revolutions of heavenly spheres or the transformations of matter. The promise of getting rid of, once and for all, secrets, doubts, ‘fear and trembling’. The promise of creating a world in which the path from action to consequences will be always and everywhere equally short and simple, as the one from pressing a button to lighting up a TV screen – a world without accidents and surprises, without disappointments and tragedies, but with a handyman available on call, ready to fix a loose button and exchange a telescopic lamp. A promise of transforming human life into a collection of problems to be solved. A promise of recipes, tools, specifications to solve every problem.

I am too much of a sociologist to accuse sociology of causing the ‘technological bias’ that deprives life of its human charm, along with its human, oh-so-human, torment and suffering. Accusing it of that is the same as directly or indirectly granting credence to its pretensions and mending the sagging pedestal on which it has placed itself (on which it has been placed?). Sociology is only a modest, secondary participant in the technological conspiracy – a messenger, an errand-boy, occasionally a minute-taker, sometimes an author of propaganda leaflets. But it is a participant in this conspiracy – even when it enters into conflict with other participants, in the name of better, more effective methods of collective action.

The history of my discouragement is lengthy and comprises many chapters. In the years of my Marxist youth, I could not digest the idea of ‘scientific ideology’; I think that this was the reason I broke out of the obediently lined-up ranks, from an idea of straightening the winding routes of history; and using unambiguous rules for doing so had a stench of corpses about it. But a rebellious nature did not allow me to seek shelter in the opposite camp; both camps pitched their tents in the graveyard of human freedom. Learned Marxist critics accused it of not being scientific enough – that its predictions did not come true; that, despite the predictions, it did not guarantee control over human actions; that the bridle which it placed on the bucking bronco of history was frayed and did not restrict the horse’s movements enough. Some wanted to ‘scientize’ Marxism; others, doubting the possibilities for success in this approach, to reject it – not because of the idea of scientific ideology, but for an insufficient, or even an entirely invented, scientificity of the ideology. From my conflicts with the Marxism of the barracks, the road led not to another camp, but to a desert, to a hermitage. Gramsci, who had dug the tunnel that I escaped through, would lead the escape committee in every one of the sociological camps of that time.

And today? I am where I began. My critics say: people need hard, strong principles – and you undermine them. People want certainty, and you sow doubt. They are right. ‘Hard, strong principles’ – coming from the revelation, or the interpretation of the secrets of history, or from a private audience in the court of Reason – are to me, in the best case, lies, and in the worst, another version of, and a functional equivalent to, Auschwitz’s ‘Arbeit macht frei.’ I repeat this as a profession of faith with a maniacal stubbornness, year after year, book after book. In various ways, expressed with various words.

I am tired. I have ridden my Rocinante almost to death; but my peregrinations were not especially picturesque. They were rather too monotonous to merit a Cervantesque smile, though they were just as successful as Don Quixote’s mission.

I cannot find the energy within myself to seek out yet another way, to find new words. And what’s worse, there is the nagging suspicion that the owners of windmills need Don Quixotes to confirm the windmill-ness of windmills and thereby to handily get rid of the unfaithful. Again, a vicious circle: using the academic mode of duelling, one can only join the academic duel, and by playing the academic game you guarantee its rules. ‘[I]t makes no sense to transgress a game’s rules’, warns Baudrillard, ‘within a cycle’s recurrence, there is no line one can jump (instead, one simply leaves the game).’15 A paradox: this is why they are merely conventions, they are ‘only’ provisional – outside of the game taking place they have no other premises, the rules of the game are invincible as long as the game continues. Those who play are players only thanks to the rules; those who refuse to play do not count. Do you want to change the rules? First you must play the game. But as soon as you join the game, you endorse the rules … The choice is between contributing to the galvanization of illusion, or silence.

Each of my successive books was – it couldn’t not be – a recreation of the academic ritual; and a protest against the ritual can be understood in the temple where the ritual takes place only as a deviation from the liturgy – and the notion of ‘deviation’ upholds the ritual in the same way as the notion of an ‘exception’ proves the rule. Just as a protest against ritual must take place in accordance with the liturgical codex. A protest against the insane grievances of the humanities regarding ‘scientificity’ must take the form dictated by academic canons and decked in all of the caricatures of academic argument required of the adepts of ‘academic humanities’.

If the knot cannot be untangled, it must be cut. That is how scissors think. At least those that, supposedly, Alexander the Great armed himself with. But knots, at least the Gordian ones, are an impossibility for scissors – just as, according to Kafka, heaven is an impossibility for crows.

Kundera – wise after reading Nietzsche, but also after his own losses and those of his countrymen – writes:

a person who thinks should not try to persuade others of his belief; that is what puts him on the road to a system; on the lamentable road of the ‘man of conviction’; politicians like to call themselves that; but what is a conviction? It is a thought that has come to a stop, that has congealed, and the ‘man of conviction’ is a man restricted; experimental thought seeks not to persuade but to inspire; to inspire another thought, to set thought moving.

Kundera calls for ‘systematically desystematiz[ing] […] thought, kick[ing] at the barricade’.16 This call, nothing strange, is directed to novelists. Whoever answers this call can only be a ‘novelist’. A teller of tales. With a wink, half-serious, half-joking. Mocking seriousness, and serious in mockery. A poet, Szymborska:

but what is poetry anyway? More than one rickety answer

has tumbled since that question first was raised.

But I just keep on not knowing and I cling to that

like a redemptive handrail.17

Cling to it! So that Maria Dąbrowska’s terrible prophecy is not fulfilled: ‘The present is like a complicated piece played on a piano with many mute, silent keys. And there will be ever more mute keys, and no one will know what piece history is playing, though there will be many words, but it will be a false tongue, like the ears of the deafmutes.’18

A paradox. A pun. A figurative expression – absorbent and porous. Self-contradiction. A substance containing its opposite, gathering and dissolving it. Such elements would comprise the logic of the humanities, cut to the size of its own subject. Or a net, which could contain the experience of being human. Other logics are simpler and more harmonious; other nets are thicker and have more tightly tied knots. So what – if those other logics fall apart when used, and those other nets return from fishing half empty?