11,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: John Wiley & Sons

- Kategorie: Religion und Spiritualität

- Sprache: Englisch

‘When your grandpa was in hospital, he asked me one night to promise him that, when he had gone from us, I would teach you Islam – our Islam: the Islam I grew up with … In that dark, impersonal room, he was thinking of you.’

This is why one father began to teach his daughter night after night not only about his own religion, but about that which unites all believers, about God and death, about love and the infinity that surrounds us. This highly personal book is not only a magical literary masterpiece, but also a rich resource of knowledge, and this because Navid Kermani dares to venture into the darkness in order to give expression to our confusion. And because his way of talking, his openness, his knowledge which derives from his immersion in two cultures, are so unique, so light and so deep.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 351

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Ähnliche

CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

The Endlessness that Surrounds Us

And in Our Selves

Extra Section on Spirit and Quantum Physics!

End of the Extra Section on Spirit and Quantum Physics!

Yes, I Testify

In a Relationship

Something Bigger than Us

Black Light

Short and Sweet

Extra Section for Everyone Who Wants to Learn a Little Arabic!

End of the Extra Section for Everyone Who Wants to Learn a Little Arabic!

From Gods to God

To God Belongs the Orient, to God Belongs the Occident

The Tail Wags

He, It – or Maybe She After All?

The Dark God

If You Doubt, You Think

Extra Advance Section on Tradition!

Everyone Is a Caliphess

Jesus’ Wisdom

End of the Discussion of Sacrifice, for Now!

Extra Section on the Difference between Christian and Islamic Architecture!

End of the Extra Section on the Difference between Christian and Islamic Architecture!

Will and Knowledge

Beginning of the Chapter Proper!

Extra Afternoon Section on Johann Wolfgang von Goethe!

Reblochon, Pecorino and Appenzeller

Sudden End of the Ingenious Ground-breaking Theory!

The Centre of the Universe

A Brief Supplement about Equality!

End of the Extra Section on Equality!

Life Itself

The Big Maybe

Epilogue

How This Book Came to Be

End User License Agreement

Guide

Cover

Table of Contents

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Begin Reading

End User License Agreement

Pages

iii

iv

v

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

108

109

110

111

112

113

114

115

116

117

118

119

120

121

122

123

124

125

126

127

128

129

130

131

132

133

134

135

136

137

138

139

140

141

142

143

144

145

146

147

148

149

150

151

152

153

154

155

156

157

158

159

160

161

162

163

164

165

166

167

168

169

170

171

172

173

174

175

176

177

178

179

180

181

182

183

184

185

186

187

188

189

190

191

192

193

194

195

196

197

198

199

200

201

202

203

204

205

206

207

208

209

210

211

212

213

214

215

216

217

218

219

220

221

222

223

224

225

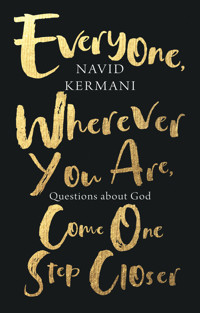

Everyone, Wherever You Are, Come One Step Closer

Questions about God

NAVID KERMANI

Translated by Tony Crawford

polity

Originally published in German as Jeder soll von da, wo er ist, einen Schritt näher kommen: Fragen nach Gott © 2022 Carl Hanser Verlag GmbH & Co. KG, Munich

This English edition © Polity Press, 2023

The translation of this book was supported by a grant from the Goethe-Institut.

Polity Press65 Bridge StreetCambridge CB2 1UR, UK

Polity Press111 River StreetHoboken, NJ 07030, USA

All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purpose of criticism and review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher.

ISBN-13: 978-1-5095-5628-1

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2022948538

The publisher has used its best endeavours to ensure that the URLs for external websites referred to in this book are correct and active at the time of going to press. However, the publisher has no responsibility for the websites and can make no guarantee that a site will remain live or that the content is or will remain appropriate.

Every effort has been made to trace all copyright holders, but if any have been overlooked the publisher will be pleased to include any necessary credits in any subsequent reprint or edition.

For further information on Polity, visit our website:politybooks.com

Dedication

With Raha for Ayda

The Endlessness that Surrounds Us

When your grandpa was in hospital, he asked me one night to promise him that, when he had gone from us, I would teach you Islam – our Islam: the Islam I grew up with, the Islam he too had experienced as a child in Isfahan; the Islam of our ancestors. In that dark, impersonal room, he was thinking of you.

Since then I’ve read aloud to you from this book and that, but none of them was what your grandpa wanted. You’ve learned a great deal about the Prophet and the country he was born in; about commandments and prohibitions; about scriptures, prayers, feasts and customs; about the difference between Sunnis and Shiites; you even know now about the four schools of law, and you have an idea of the problems that the Islamic world faces today. But what Islam is really about, and not just Islam, but all religions, when you get to the bottom of it – why we say we believe in God – you’ve learned hardly anything about that. It’s as if the books were describing a person’s clothes without saying a word about the person wearing them – their face, their character; not even whether it’s a man or a woman, young or old; where they come from, what their dreams are, and why they love us. If religion had any deeper meaning at all in those books, it was in bringing us up to be decent people – to be just, kind, helpful and so on. But can’t a person figure that out just as well, you asked, without God?

At that I stammered something about loving your neighbour, compassion, the Ten Commandments. But later, lying in bed, I thought: of course you can figure that out without God. After all, atheists are not murderers, thieves or swindlers just because they don’t believe in God. And at the same time, there are so many people who do believe in God and yet are unjust, hard-hearted and cruel. So the religions must be about something more besides how we shape our lives and how we behave towards our fellow human beings. Maybe they’re also, and most of all, about life itself: about what this life that we have is, and whether it consists of something more than what we see.

Some people say life is what it is: the result of chemical, molecular and genetic processes, a kind of supercomputer that is constantly developing itself by trial and error, adaptation and selection, cause and effect. Grandpa always pointed out that someone must have built and programmed this computer that makes everything tick. And when others insisted, no, there is no one who builds and programs life; it comes about by itself and disappears again like a drop of water that evaporates and dissolves into thin air – then Grandpa always said something that is cannot simply become nothing: neither a drop of water nor a human being nor the fact that we exist. And he claimed, furthermore, that the idea that something could become nothing is almost impossible for children to conceive of. And do you know what? I think your grandpa was right about that.

It is interesting, after all, that children, if I’m not mistaken, practically never question the meaning of life – don’t even dwell on it much, while adults certainly do. Oh yes, and how they question and dwell! So there must be something between being a child and being an adult that shakes our belief that everything is just as it should be. Try to remember when you were a little child: did you use to think a lot, about death for example, when you were younger? I don’t think you did, really. You knew that we all die someday, but it wasn’t something you thought about; to you it seemed as though life would just go on somehow. You weren’t afraid at all; on the contrary – when I talked about the afterlife, about Heaven, angels and eternal life, it was the most natural thing in the world to you. You simply couldn’t imagine that something that is could suddenly not be, from one breath to the next.

Only now that your own grandpa has died, and you’ve grown older yourself – at twelve you’re almost a teenager – have you met death face to face. You wept at his grave. You noticed something was wrong; Grandpa is gone; he’ll never tell you a story again; you’ll never go visit him by the seaside in summer. Maybe you’ve thought for the first time about the fact that you too will lie in the ground one day, in one of those cold, clammy graves. That we all will turn to dust: your mother, your father, your sister. And I think this conscious confrontation with death is one of the things that happens between being a child and being an adult. It doesn’t have to be a certain person who dies; what I mean is simply the clear realization that someday we won’t be around any more, none of us. And two, three or at most four generations after us, there won’t be anyone left around who remembers us either.

Know that earthly life is but a game

And an amusement and a frippery and a contest,

Who is the richest, who has the most children.

It is as rain that makes the plants sprout,

And makes the whole village glad.

Then they wither, and you see them turn yellow and dry.

And everything decays.

Of course, our great- or great-great- or great-great-great- grandchildren will know we existed – otherwise they wouldn’t exist. But who we are, what we think, feel, dream, what makes us feel concerned, angry, glad, afraid or excited: they won’t have the slightest clue about that. We’ll just be gone, as if erased; not even our names will be known; even the inscription on our tombstone will weather and become illegible, no more recognizable than our faces in old photos. All the people we loved, and we ourselves too, will evaporate like a drop of water – into nothing, it seems.

Sooner or later each of us realizes with a chill that nothing of us will last. Then we begin to doubt: does life really go on somehow when a person dies, as our parents always said? And where was I before I was born? Sooner or later, every human being wonders about questions like these, and their answers differ vastly. But perhaps it is not the adults who know best with their long and their short explanations, but the children, who trust that life will go on somehow and everything is as it should be. And the Quran – and all revelations, for that matter – confirm what children think. They say, just look around you – do you really think all this can be just by chance?

Look at the water you drink –

Did you send it down from the clouds, or did We?

If We wanted, We could make it bitter.

Why then do you not give thanks?

Look at the fire you have kindled –

Did you create the wood, or did We?

We created it as a reminder

And to serve those who cross the desert.

Therefore praise the name of your Lord Who is almighty.

And yesterday, as my gaze strayed out of the window while we were reading another book about Islam, I suddenly thought there is more to learn about God out there, or at least more important things than the fact that the Quran contains 114 surahs and what the first, second, third, fourth and fifth pillars of Islam are. After all, Islam and Christianity and Judaism and all the other religions were not created in offices, in libraries or in classrooms. The religions came into being wherever people looked around at nature, or worried about their loved ones when they themselves were sick, hungry or feeling lost, when their children were born or when their parents died – at the most important events there are in a person’s life. And why? Because they noticed they were surrounded by endlessness. Yes, endlessness. The sky, for example, up there, if you look out of the window right now – not the Earth’s atmosphere, I mean, but the universe, space – does it have an end? No, of course not. But can you imagine that something just goes on, goes on and on forever? Think about what that means. You’ll find that you can’t imagine endlessness.

Or take the chestnut tree in the yard – yes, that one: can you conceive that out of trillions and quadrillions of leaves that have sprouted since the world began, not a single one is the same as another? I mean, not only each one of that tree’s leaves is different from every other, even if you could lay every leaf the tree ever grew side by side – but all the leaves of all the trees of all time: not a single leaf that ever grew or ever will grow is the same as any other. And there you have another endlessness, an endless diversity this time – one that you can see but can’t explain, much less produce yourself. But this amazement, the amazement at all the things, occurrences and phenomena in the world, which you can see but can’t explain because they exceed our limited understanding – some of them frightening, many amazingly beautiful – precisely this amazement is the origin of Islam, and of all religions. Because all of us, your grandparents, your parents, you, your sister, and one day your children and grandchildren, all of us are born and eventually die. Just like the leaves of the chestnut tree in the courtyard, and like every creature on Earth, we flourish and wilt. Not even the stones, the lifeless, unremarkable pebbles lying around in the yard, have always existed, nor will they always exist. Something must have existed before the stones, before the buildings, streets, churches of our city, before the huts and the paths, before the people who settled here; some kind of field I suppose, a ploughed field, and before the fields, the riverbank was lined with meadows and bushes, or the land was covered with primeval forests. But the meadows and forests weren’t always there either, nor even the river. Before that, perhaps there was ice, or maybe just rocks; maybe this was all a sea at one time. In any case, even the rocks came into being only gradually; they formed over thousands or millions of years, and in thousands or millions of years more, there will be nothing left of them. Not even the rocks! In other words, everything that exists is finite; it begins, and at some point it ends. But the sky – the sky never ends.

When the Earth no longer exists, there will still be the sky, whether there are stars in it then or not. And there is no limit to the diversity of shapes that a leaf can take either. Even if the world were to go on existing for millions and millions of years, Nature would still find a new shape for every single leaf of every single tree – just as it does for the face, the hands, the toes, the fingertips and the eyelashes, if you like, of every single person who ever lived or ever will live. Nothing is the same as anything else, absolutely nothing – not even eyelashes! That’s what I meant when I said we are surrounded by endlessness.

And that is where religion arises: it is a relationship between the finite beings that we are and the infinite, which is also called God. And that is the subject of the book I want to write – no, I have to write: the book I promised your grandpa shortly before he died. We’ll write it together, rather: every evening I’ll read you the notes I’ve made while you’re in school, and the next day I’ll start with your questions and objections. And maybe it won’t be a book just about Islam, but about what’s common to all religions. We’ll see where you lead us.

And in Our Selves

Okay, you’re right: if no hand is the same as another, you said yesterday, then we’re endless too. Or, to put it more precisely, although we are mortal, we too are part of an infinite diversity. On the spur of the moment I couldn’t think of a rebuttal, but this morning, while I was brushing my teeth, I thought: each of us, every living thing, carries something endless in ourselves. You could also say that is the divine in us. But, at the same time, every one of us, and likewise every leaf on the chestnut tree in the courtyard, has a beginning and an end: we are born and we die, we grow and decay. This finiteness is the terrestrial in us. That means every person, and every creature of any kind, carries in itself the relationship between the infinite and the finite. Or, in other words, the divine is not something external, but lies in ourselves. We are mortal and hence human, but in our uniqueness – yes, precisely by the fact that we are unique and unmistakable and unrepeatable – we are part of an endless diversity, and hence divine.

That sounds a little bit like inspirational Sunday radio, I’m afraid. And yet it’s actually physics – quantum physics, in fact. Quantum physics studies the tiniest building blocks of matter – molecules, atoms and much smaller elementary particles, millions of times smaller than anything we can see with the naked eye. So small it makes even physicists woozy.

Because, actually, physics is the study of what we call reality. The word ‘reality’ comes from the Latin res, which means ‘a matter’ or ‘a thing’. I can take a thing in my hand – an apple, let’s say – and that’s reality. The apple in my hand is real. God, on the other hand, would be an assertion that you either believe in or don’t: in other words, religion.

But it’s not as simple as that; at least, not in Islam. And not in physics either. Because physics has discovered that these tiniest building blocks of existence don’t exist – not in the ordinary sense of the word at least, as something with clear boundaries, much less something you could put your finger on. In other words, not only in outer space or on other planets, not only in science fiction or religion – no, in each one of us, too, there is a reality that is different from everything we know.

On Earth are signs for the sure in faith

And in yourselves – do you not see?

That other, inner reality obeys other laws; it has a different structure from our reality; we can’t call it what it is with the words we have. In that reality, particles are in different places at the same time; they react to each other no matter how far apart they are; they can jump from one place to another without passing through the space in between. And nothing can be predicted by exact calculations, because the principle of cause and effect doesn’t always apply. It’s a reality without ‘matter’ or ‘things’.

God, as your grandpa explained Him to me, is not so very different. Strictly speaking, Grandpa didn’t believe in God at all: he saw God, he grasped God – really, the way you grasp something with your hand; he smelled God – the way you see, grasp, smell an apple. Indeed, by saying ‘God’, Grandpa created Him, in a sense: that is, he gave an expression to that which exists only for itself, just as the apple only becomes ‘an apple’ in your mind. The apple is already there, but it has no name; it doesn’t belong to any category of fruits; it just exists – no, it ‘functions’; it grows from a bud, ripens in the sun, becomes food for an animal or falls to the earth, to which it returns as it gradually decomposes. It is human beings who give this reality a name which is distinct from those of other realities: apple. Not tree, not pear, not hand. And, in Islam, God – this is perhaps the most important thing of all that your grandpa tried to teach me, and my grandparents thought the same – in Islam, God is just as real as an apple, or a breath of wind or, you could also say, a feeling such as love or fear. Only different from all the things we know. Not a person, not an animal, not a fantasy.

Okay, what then? you will probably ask. What is He like, this God, and where, and how come? And yet, you yourself phrased it very similarly yesterday evening – all right, you didn’t talk about quantum physics, but you did mention an essential principle of it when you said we too, although we are finite, are nonetheless part of infinity. I’ll try to explain that – but I’m warning you, it’s going to get a bit complicated. If you’ve had enough of physics already, just bring back your mind at the end of the ‘Extra Section’.

Extra Section on Spirit and Quantum Physics!

Imagine you’re looking closer and closer at an object – let’s say one of the leaves of the chestnut tree – up close first, then with a magnifying glass, then under a microscope, and so on: you divide the leaf into tiny parts and split one of those parts again, and again; first a cell, then a molecule, until you get to the atoms, but then you split one of the atoms into its parts, and then you come to the subatomic particles, the electrons, neutrons and protons.

And, for every particle, there is an anti-particle with the opposite charge, and they can change into one another or release energy when they collide. Then they cancel each other out, and emit two light particles, photons, in their place. If you keep on looking closer, you’ll find that the subatomic particles are made of quarks, which are connected to other quarks as if by an invisible thread, and between them … is nothing: no body, only an oscillation, energy, interaction or potential.

Those are fuzzy words, I know, but not even quantum physics, the most precise of all the sciences, has unambiguous words for it – because the phenomenon itself is ambiguous. For quantum physics has discovered – and this was perhaps the greatest scientific revolution of the twentieth century, on which all of today’s technologies are based, not only atomic energy, but also computers, lasers, magnetic resonance tomography, solar energy and the Internet, down to your smartphone – quantum physics has discovered that our existence, at its core, is not matter, something material, but something else, something unnameable which is actually not ‘matter’ and not a ‘thing’ – a reality without a res. Because words refer to concepts, which means something that you can grasp, or feel, or at least circumscribe. Words work in a world of either–or: either it’s the apple, or it’s the hand holding the apple.

But if you keep splitting an object into its component parts (better the apple than the hand!), and keep splitting and splitting, in the end there is no object left, only something that you can’t explain, define, grasp with your mind; at most you can only observe it, describe it, and be amazed at it.

For example, physicists discovered that the same subatomic particle – something much smaller than an atom – behaves like an object, and at the same time like a wave. That’s not possible, the quantum physicist’s brain thought. But the measurements showed that something can be its opposite at the same time: an object and a non-object. It is beyond our words and concepts – but it exists. Yes, and what’s more: ultimately, only this One, Indivisible, Immaterial exists, and all life develops from it, just as a single cell becomes many by cell division – except that this One isn’t a cell, but something more airy, more of the nature of a process.

Airy, I said just now. The word is not so poorly chosen, since even rigorous quantum physics sometimes can’t find a better word for this One Thing than ‘spirit’. One of the founders of quantum theory, Werner Heisenberg, even said once that the Greek philosopher Plato was quite right: the real world is that of forms, and we can see only shadows of it. And Heisenberg’s daughter Christine reported that her father’s eyes glowed with joy as he spoke, like the eyes of a child receiving a huge present. This world, Heisenberg attested time after time, this inner world that holds all the outwardly graspable things together is so unbelievably beautiful that it takes your breath away.

Beauty – I thought that was something you can see or hear or smell. Not something abstract, something thought up; not just empty space. And spirit is first of all formless, and thus unbounded, but at the same time it is associated with a certain being, or sometimes with a group or an era. The Arabic and Persian languages, and also Greek, English and the Indian languages, frame this contrast clearly: for ruḥ, nafs, pneuma, spirit and atman all go back to the sense of ‘breath’ or ‘puff of wind’. This seems to be a general awareness among humanity: that breathing is not just the most elementary activity of every person, but the fundamental principle of life itself. You still have some of this knowledge in the biblical German word Odem, which is related to the modern word Atem: God breathed His Odem into Man, that is, He breathed His spirit into him, He breathed life into him.

‘Spirit’ in this sense is thus not only something spiritual, immaterial, but at the same time something physically perceptible, tangible, like air. And the critical thing is – you brought it to my attention yesterday – that all of us are part of this same One that contains so many possibilities. Whenever you draw a breath, you’re connected with the whole world. Every time you breathe out, the world receives part of you.

End of the Extra Section on Spirit and Quantum Physics!

So ‘spirit’ or ‘breath’ would be a second metaphor for God, after endlessness which I talked about yesterday. After all, human beings didn’t always have microscopes, much less the ability to split atoms. But they have always felt the air filling up their chest, rising and falling, invisible, inexplicable, and yet real. The most important thing of all in life, the most personal, and at the same time something that exists in every creature – and you have no power over it! You can hold your breath if you want, but afterwards you’ll exhale all the more vigorously. Neither were you able to control your first breath, nor will you have any power over your last breath. You are completely dependent on an external power, a ‘spirit’, that awakens you with your first breath, and sustains you a long time, I hope, before it takes your life back again. And this principle – that human beings must gasp for air because by nature they want to live, no matter how unpleasant and difficult their existence may be – this principle is present everywhere in nature.

People saw the plants and animals all around growing and decaying, the sun and the moon, the earth and the seas giving them food and taking all the bodies after their death, and they felt – from the beginning of time people felt that the world is not put together out of independent parts, but that there is a common fundamental principle at work in everything: ‘the breath of the All-merciful’, as the world is called in Islam. Yes, the whole of Creation is the ‘breath of the All-merciful’. For Grandpa, this fundamental principle existed, this oneness, the tawḥīd, just as undoubtedly as in physics something exists beyond or before or between our world of objects. Except that, in religion, you don’t need a laboratory; a look out the window or a single breath tells you enough. God is not something you just believe in; God is something you see if you look closely.

Don’t pursue what you know nothing about;

For it is the ears, eyes, heart

Which shall be called to account.

By the way, about your smartphone: how do you explain the fact that you just have to press a couple of buttons and you’re connected with Aunt Jaleh in Iran? Telephones used to be connected by wires, sure, and I once read you a story about the first cable being laid between Europe and America in the nineteenth century, by two ships sailing towards each other – what a sensation that was in those days. Maybe I’m a bit old-fashioned, but I always thought that today, instead of a cable, there was some kind of antenna, and this antenna sends out some kind of vibrations, and they cause another vibration, and so the vibrations go out across the ether to a satellite, and from the satellite back down again to Aunt Jaleh’s phone, something like waves on the ocean. Only recently I learned that there is no ether. That is, the waves have no material medium; there’s nothing there to vibrate, not even the thinnest air. It’s as if waves rolled across an ocean although there was no water. And yet Aunt Jaleh’s phone rings in Isfahan. Would God then be the ocean that isn’t there, or the wave that nonetheless travels from one shore to the other? Or both, or nothing? Think about that.

Your grandpa was not a physicist, but as a doctor he had a scientific view of the human body, and likewise of nature in general. I’m sure he himself treated many people in the hospital who were beyond curing: he knew the constantly growing capabilities of medicine, and the limits that it will never overcome. There is a strange sentence he always said, and that his grandpa had probably said too, and his grandpa and his grandpa, and all our grandmas and great-grandmas too: ‘Hold on tight to God’s rope.’ God is everything, and hence eternal and unlimited. But His breath is very specific. God is both.

Yes, I Testify

Oh my God – if I’d known you were going to get so enthusiastic about quantum physics, I wouldn’t have said anything about it. Because now you’re pestering me with questions about force fields, probability waves and the quantization of energy. Am I Stephen Hawking? If only I’d stuck to the Quran! Then you wouldn’t be asking me about the miracles; you would have accepted them as natural, as in any other story. You’re right: a smartphone is a technical device that can be explained and built. But for Jesus to be born with-out a biological father, walk on water or wake the dead will always be inexplicable – if it really happened at all.

Now I could make the excuse that that’s the Christians’ problem: after all, Jesus is their Messiah, not ours. Fortunately for your common sense, and my parental duty, Muhammad never performed any supernatural feats. But that wouldn’t get me far, because you would rightly point out that Islam explicitly recognizes Jesus’ miracles.

All right, I could still say those miracle stories were meant only metaphorically. The virgin birth, for example, would be the Bible’s way of saying that Jesus was sent by God, and not the product of a man’s semen. But that might be taking an easy way out; in any case, your next objection would inevitably be: then why is Jesus the product of a woman’s egg?

Well, instead of pursuing what I know nothing about (Surah 17:36 from yesterday!), let’s read Surah 19, starting at verse 16, where the Quran tells about Mary’s pregnancy.

And in the Book recall Mary

When she went away from her people

Towards the East

And hid herself.

We sent to her Our spirit [literally, ‘breath’, ‘puff of air’!]

Which appeared before her as a well-formed human being.

‘I take refuge before you in the All-merciful’, she cried,

‘Maybe you fear Him.’

‘I am a messenger of your Lord’, he said,

‘To bestow on you a good son.’

‘How can I have a boy’, she asked,

‘When no man has touched me,

And I am not a whore?’

The spirit said, ‘Thus says your Lord to you:

“That is easy for Me;

And so We will make the child a sign to the people,

And a mercy from Us.

The matter is decided.”’

She conceived him

And went with him to a place far away.

Now don’t shout right away that the whole thing about the virgin birth is complete nonsense. Try at least to understand the difference between this version and the Christian story. There will still be time to tell me I’m off my rocker. The difference is that, in an Islamic concept of the world, Mary’s pregnancy is not a miracle in the way we think of miracles today – as something supernatural. In the Quran, Mary’s pregnancy is no more unusual than nature itself. That’s why your grandpa, who otherwise saw everything so rationally and scientifically, was never much amazed at Jesus not having a biological father. Why should he be? he said, when he heard how Christians today discuss the idea; he was much more amazed at the discussion! Because the sense of the Quran is, rather, that if we look only for superficial causes and effects, and don’t take the spiritual world into account, our understanding of reality just isn’t deep enough. The universe too is an indisputable physical fact, and we can investigate it scientifically and trace it back to the Big Bang. But we will never understand why the world began if we search for the reasons only within the world.

See, to God, Jesus is the same as Adam:

He created him from earth, and then He said to him,

‘Be!’ and he was.

Still not convinced? Just wait; you’ll live to see much bigger miracles. No, you already have: starting with your own birth. You could retrace every effect to every possible cause, back to the beginning of time theoretically, and never find the reason why there exists something rather than nothing. Maybe the virgin birth is really only a picture, a story, a metaphor; but you yourself, your eyes, your nose, your belly, your laugh that makes me laugh too every time, no matter how sad I may be – you exist. In Islam, both the virgin birth and life itself stand for this same inexplicability: we see something and can’t possibly deny it, and although our rational mind is not sufficient to discover its cause, that doesn’t imply at all that the cause doesn’t exist.

Now maybe you’ll say people didn’t yet understand the cause in those days, but today we’re further along; we can explain why a person comes into being, from fertilization to mitosis – cell division – to birth. In that case, I’ll ask you: but why is there cell division; why are there cells; why are there atoms? If I keep on asking, I always come to a point where even science runs out of answers. Science, I would claim, can’t even explain the love that draws two people together to conceive a child like you.

It’s no wonder that the proportion of people who believe in God is much higher among physicists and mathematicians, who deal with unimaginable things day in and day out in the course of their research, than among sociologists or psychologists. Yes, there are studies! And if you doubt me again, google it yourself. Almost all of the pioneers of quantum physics in particular found their way to religion sooner or later, although it wasn’t always Christianity, Judaism or any specific denomination. ‘That deeply emotional conviction of the presence of a superior reasoning power, which is revealed in the incomprehensible universe, forms my idea of God’, said Albert Einstein. Einstein believed in God, not although he was a scientist, but because he was a scientist. In other words, to him, science and faith, rationality and spirituality, complemented each other. ‘The cosmic religious experience is the strongest and noblest mainspring of scientific research.’

I know it is still unusual, eighty years after Einstein, to think of science and religion together. In your school, the two subjects are kept strictly separate, I assume – Religious Education being classified, rather, under ethics or philosophy. And a miracle, colloquially, is something you believe, or don’t as the case may be: a miracle violates the laws of physics. In Islam, on the other hand, those laws that you perceive behind all phenomena are themselves the miracle. There is a reason for everything in this Creation, absolutely everything, however tiny and insignificant every single living thing may be individually, and even for the most unusual, arbitrary, randomly acting, astounding thing. For every single one of us.

And the mountains that you think are immovable,

You shall see passing as the clouds:

The work of God, Who has ordered every thing.

And He is aware of what you do.

Why do you suppose I’m a Muslim? Sure, I’m a Muslim because my parents and my ancestors were Muslims and set me an example, encouraged me, trained me in Islam. If I had been born in a Christian household, I would very probably be a Christian today. When you look at it that way, it was by chance that I became a Muslim. Just as it is by chance that your father isn’t encouraging you to become a Buddhist, for example.

I could have decided against Islam at some point, however. The Quran emphasizes over and over again that faith must be based on your own experience, your own thinking, your own insight. Among the five roots or principles of faith, the uṣūl, which are much more important to us than the famous five pillars, arkān, that your school’s explanation of Islam makes so much of – among the five principles, many Muslims count Reason (ʿaql) third, right after the Unity of God (tawḥīd) and the Prophecy (nubūwa), but before Justice (ʿadl) and belief in the Resurrection (maʿād). That’s why in Islam a person is supposed to choose the religion consciously only when they are 13, 14 years old – that is, when they reach the age of consent. Surah 2, verse 170, goes as far as to explicitly criticize people who blindly follow the belief of their fathers: ‘But what if their fathers didn’t understand anything?’

Every day there are stories in the news that reflect poorly on Islam. In Iran, where we come from, the people are oppressed in the name of Islam. In the Quran itself, I come across verses that alarm me. Why then have I not turned away from Islam? Why am I – although I have travelled so much and visited countries where the conception of Islam is narrow-minded and even violent, although I have read so many books, on other religions as well as Islam – why have I, in full knowledge of the facts, remained a Muslim?

This part is going to be more complicated – or, come to think of it, maybe not. I am a Muslim because I can say the profession of faith, the shahāda: There is no God but God, and Muhammad is His prophet. If you agree with these two statements, you are a Muslim, and no one may cast doubt on your faith; no one has the right to ask you anything else about it, or to contend that you’re a bad Muslim. Everything else, the five principles of faith, the five pillars, the prohibitions and commandments – they are important; they are recommended; but they do not determine whether you are a Muslim or not.