16,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

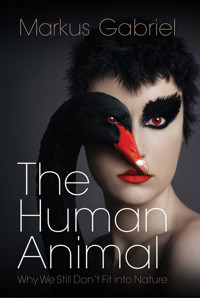

- Herausgeber: John Wiley & Sons

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

Many consider the nature of human consciousness to be one of the last great unsolved mysteries. Why should the light turn on, so to speak, in human beings at all? And how is the electrical storm of neurons under our skull connected with our consciousness? Is the self only our brain’s user interface, a kind of stage on which a show is performed that we cannot freely direct?

In this book, philosopher Markus Gabriel challenges an increasing trend in the sciences towards neurocentrism, a notion which rests on the assumption that the self is identical to the brain. Gabriel raises serious doubts as to whether we can know ourselves in this way. In a sharp critique of this approach, he presents a new defense of the free will and provides a timely introduction to philosophical thought about the self – all with verve, humor, and surprising insights.

Gabriel criticizes the scientific image of the world and takes us on an eclectic journey of self-reflection by way of such concepts as self, consciousness, and freedom, with the aid of Kant, Schopenhauer, and Nagel but also Dr. Who, The Walking Dead, and Fargo.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 540

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Ähnliche

Contents

Cover

Table of Contents

Dedication

Title Page

Copyright

Epigraph

Introduction

Mind and Geist

Elementary particles and conscious organisms

The decade of the brain

Can the mind be free in a brain scan?

The self as a USB stick

Neuromania and Darwinitis – the example of Fargo

Mind – brain – ideology

The cartography of self-interpretation

Notes

1 What is at Stake in the Philosophy of Mind?

Mind in the universe?

In the spirit of Hegel

The historical animal on the social stage

Why not everything, but at least something, is teleological

Notes

2 Consciousness

I see something that you do not see!

Neuronal thunderstorms and the arena of consciousness

Buddha, the snake and the bat – again

Surfing on the wave of neuro-Kantianism

Nothing is beyond our experience – or is it?

Faith, love, hope – are they all just illusions?

An altruist is lodged in every ego

Davidson’s dog and Derrida’s cat

Tasty consciousness

The intelligence of the robot vacuum cleaner

Strange Days – the noise of consciousness

What Mary still doesn’t know

The discovery of the universe in a monastery

Sensations are not subtitles to a Chinese movie

God’s-eye view

Notes

3 Self-Consciousness

How history can expand our consciousness

Monads in the mill

Bio is not always better than techno

How the clown attempted to get rid of omnipotence Self-consciousness in a circle

Notes

4 Who or What is This Thing We Call the Self?

The reality of illusions

Puberty-reductionism and the toilet theory

Self is god

Fichte: the almost forgotten grandmaster of the self

The three pillars of the science of knowledge

In the human being nature opens her eyes and sees that she exists

“Let Daddy take care of this”: Freud and Stromberg

Drives meet hard facts

Oedipus and the milk carton

Notes

5 Freedom

Can I will not to will what I will?

The self is not a one-armed bandit

Why cause and reason are not the same thing and what that has to do with tomato sauce

Friendly smites meanie and defeats metaphysical pessimism

Human dignity is inviolable

On the same level as God or nature?

PS: There are no savages

Man is not a face drawn in the sand

Notes

Index

End User License Agreement

Guide

Cover

Table of Contents

Dedication

Title Page

Copyright

Epigraph

Introduction

Begin Reading

Index

End User License Agreement

Pages

ii

iii

iv

vii

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

108

109

110

111

112

113

114

115

116

117

118

119

120

121

122

123

124

125

126

127

128

129

130

131

132

133

134

135

136

137

138

139

140

141

142

143

144

145

146

147

148

149

150

151

152

153

154

155

156

157

158

159

160

161

162

163

164

165

166

167

168

169

170

171

172

173

174

175

176

177

178

179

180

181

182

183

184

185

186

187

188

189

190

191

192

193

194

195

196

197

198

199

200

201

202

203

204

205

206

207

208

209

210

211

212

213

214

215

216

217

218

219

220

233

234

235

236

237

238

239

240

241

242

243

244

245

Dedication

For Marisa LuxBecome who you are!

I am Not a Brain

Philosophy of Mind for the Twenty-First Century

Markus Gabriel

Translated by Christopher Turner

polity

First published in German as Ich ist nicht Gehirn. Philosophie des Geistes für das 21. Jahrhundert © by Ullstein Buchverlage GmbH, Berlin. Published in 2015 by Ullstein Verlag.

This English edition © Polity Press, 2017

Polity Press65 Bridge StreetCambridge CB2 1UR, UK

Polity Press111 River StreetHoboken, NJ 07030, USA

All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purpose of criticism and review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher.

ISBN-13: 978-1-5095-1478-6

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication DataNames: Gabriel, Markus, 1980- author.Title: I am not a brain : philosophy of mind for the 21st century / Markus Gabriel.Description: Malden, MA : Polity, 2017. | Includes bibliographical references and index.Identifiers: LCCN 2017010106 (print) | LCCN 2017030527 (ebook) | ISBN 9781509514779 (Mobi) | ISBN 9781509514786 (Epub) | ISBN 9781509514755 (hardback)Subjects: LCSH: Philosophy of mind. | Consciousness.Classification: LCC BD418.3 (ebook) | LCC BD418.3 .G33 2017 (print) | DOC 128/.2--dc23LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017010106

The publisher has used its best endeavours to ensure that the URLs for external websites referred to in this book are correct and active at the time of going to press. However, the publisher has no responsibility for the websites and can make no guarantee that a site will remain live or that the content is or will remain appropriate.

Every effort has been made to trace all copyright holders, but if any have been inadvertently overlooked the publisher will be pleased to include any necessary credits in any subsequent reprint or edition.

For further information on Polity, visit our website:politybooks.com

… as we remind ourselves that no age has been more skillful than our own in producing myths of the understanding, an age that produces myths and at the same time wants to eradicate all myths.

Søren Kierkegaard, The Concept of Anxiety

Introduction

We are awake and thus conscious; we have thoughts, feelings, worries and hopes. We speak with each other, found states, choose parties, conduct research, produce artworks, fall in love, deceive ourselves and are able to know the truth. In short: we humans are minded animals. Thanks to neuroscience we know, to some extent, which areas of the brain are active when someone shows us a picture, for instance, or prompts us to think of something in particular. We also know something about the neurochemistry of emotional states and disorders. But does the neurochemistry of our brain ultimately guide our entire conscious mental life and relations? Is our conscious self only our brain’s user interface, so to speak, which in reality does not contribute at all to our behavior but only accompanies what actually happens, as if it were an unimportant spectator? Is our conscious life thus only a stage upon which a show is performed, in which we cannot really – that is, freely and consciously – intervene?

Nothing is more obvious than the fact that we are minded animals who lead a conscious life. And yet, this most evident fact about ourselves gives rise to countless puzzles. Philosophy has occupied itself with these puzzles for millennia. The branch of philosophy that is concerned with human beings as minded animals, these days, is called philosophy of mind. It is more relevant today than ever before, as consciousness and the mind in general are at the center of a whole variety of questions for which we currently have nothing that even comes close to a full explanation in terms of our best natural sciences.

Many consider the nature of consciousness to be one of the last great unsolved puzzles. Why, anyway, should the light turn on, so to speak, in some product of nature? And how is the electrical storming of neurons in our skull connected to our consciousness? Questions such as these are treated in subfields of the philosophy of mind, such as the philosophy of consciousness, and in neurophilosophy.

Thus it is here a question of our very selves. I first present a few of the main thoughts of the philosophy of mind with reference to central concepts such as consciousness, self-consciousness and self. In the wider public and in various disciplines outside of philosophy, there is much talk about these concepts, mostly without awareness of the philosophical background, which leads to confusion. Hence, to start out with, I discuss this background with as few philosophical assumptions as possible.

My sketch of the philosophical background of many of the conceptual building blocks of our self-understanding as minded animals forms the foundation of the second main goal of this book: the defense of our freedom (our free will) against the common idea that someone or something deprives us of our freedom unbeknown to us – whether it be God, the universe, nature, the brain or society. We are free through and through, precisely because we are minded animals of a particular kind. The particularity of our mind consists in the fact that we constantly work out a historically shifting and culturally varying account of what exactly it takes to be the kind of minded animal we are. Whereas some believe that we have an immortal soul which accounts for the various mental processes we constantly experience, at the other extreme end of possibilities, many are happy to accept that all their mental processes are ultimately identical to brain states.

In this book, I argue that the truth indeed lies between these untenable extremes (and their more sophisticated versions spelled out by contemporary philosophers and mind scientists of various stripes). Here, the main idea is that what we call “the mind” is really the capacity to produce an open-ended list of self-descriptions which have consequences for how humans act. Humans act in light of their self-understanding, in light of what they believe to be constitutive of a human being. For instance, if you believe that your capacity to act morally presupposes that your soul has an immortal nature, you will live differently from someone who (like me) is convinced that they will live only once and this is the source for our ethical claims. Given that nothing would matter to us at all if we weren’t conscious, sentient creatures with beliefs about what that very fact means, anything which matters to us, anything of any importance hinges on our self-conception as minded. However, there is a vast plurality of such self-conceptions spread out through human history as we know it from the writings and cultural artifacts of our ancestors as well as from the cultural variation across humanity as we find it on our planet right now.

It will turn out that we are neither pure genetic copying machines, in which a brain is implanted giving rise to the illusion of consciousness, nor angels who have strayed into a body but, in fact, the free-minded animals whom we have considered ourselves to be for millennia, animals who also stand up for their political freedoms. Yet, this fact about ourselves is obscured if we ignore the variation built into the capacity to conceive of oneself as minded.

Mind andGeist

Let me give you an example of the variation we need to explore. Remarkably, there is no real equivalent of the English word “mind” in German. Likewise, the German word Geist, which plays a similar role as mind in English, cannot be translated in a literal way – that is, without further explanation. Here are more elements in a list of terms that have a whole variety of meanings even within English and which cannot easily be translated into every language: consciousness, the self, awareness, intuition, belief, cognition, thinking, opinion. Let us call the vocabulary in which our self-conception as minded animals is couched our mentalistic vocabulary. This vocabulary has different rules in different languages, and even within a given natural language, such as English or German, there is really a variety of usages tied to specific local ways of understanding ourselves as minded. Depending on the kind of vocabulary to which you explicitly and implicitly subscribe as privileged over alternatives, you will, for example, think of your mind as extended into your computer, as locked in your brain, as spread out over the entire cosmos, or as connected to a divine spiritual realm in principle inaccessible to any modern scientific investigation. However, in order to make sense of this very variation, we have to assume that there is a core concept defining human self-understanding as minded. For simplicity’s sake, my choice for the central term here is “mind.”

I am aware that this might be more misleading than in the German context in which I started to work out my views about the topic at hand. For, in the German philosophical tradition, we rather speak of Geist as the relevant invariant. However, the notion behind the somewhat mysterious term Geist can be summarized in roughly the following way: what it is to be a minded (geistig) animal is to conceive of oneself in such a variety of ways. Human beings essentially respond to the question of what it means for them to be at the center of their own lives in different ways. What does not vary is the capacity, nay, the necessity, to respond differently to this question. Our response to the question of what it means to be a human minded animal in part shapes what it is to be such an animal. We turn ourselves into the creatures we are in each case by developing a mentalistic vocabulary.

Let me give you another example. We all believe that there are pressing moral issues having to do with, say, abortion, economic equality, warfare, love, education, etc. At the same time, we all have beliefs about why we are even open to these issues. Again, here are two possible extremes. A social Darwinist will believe that morality is nothing but a question of altruistic cooperation, a behavioral pattern whose existence can be explained in terms of evolutionary biology/psychology. By contrast, a Christian fundamentalist maintains that morality is a divine challenge to humans, whose nature is corrupted by sin. This has consequences for their actions and for their answers to pressing moral questions, as we all know. In both cases, the divergence of opinion results from the way in which the social Darwinist and the Christian fundamentalist think about their mental lives. I suggest that the social Darwinist will turn herself into the kind of altruistically inclined animal she takes herself to be, whereas the Christian fundamentalist will literally have a different mindset, one in which her mind will be shaped in light of her conception of the divine. The Christian fundamentalist might be much more obsessed with the idea that God is watching and judging her every deed (and even her intimate thoughts), which will give rise to thought processes utterly absent in the social Darwinist, and vice versa.

In my view, there is no neutral ground to settle the issue, no pure standpoint from which we can start to answer the question of what human mindedness really is. For human mindedness actually exists only in the plurality of self-conceptions. If we strip it from its differentiation into a plurality of self-conceptions, we wind up with an almost empty, formal core: the capacity to create self-conceptions.

However, this formal core matters a lot, as I will also argue in what follows that this formal core necessarily gives rise to an irreducible variety of self-conceptions, and that this fact about us as minded animals is also at the center of morality in general.

Elementary particles and conscious organisms

A major challenge of our times is the attempt to come up with a scientific image of the human being. We would like to obtain objective knowledge finally of who or what the human being really is. However, the human mind still stands in the way of achieving a purely scientific story, since the knowledge obtainable only from a subjective point of view has eluded scientific research to this point. To address this problem, future neuroscience is decreed as the final science of the human mind.

How plausible is the assumption that neuroscience can finally give us a fully objective, scientific understanding of the human mind? Until recently, one would hardly have thought that a neurologist or a neurobiologist, for example, should be the specialist for the human mind. Can we really trust neuroscience in general, or brain science in particular, to provide us with the relevant information about ourselves? Do they hold the key to the secret which has haunted philosophy and humanity ever since the Delphic oracle told us to know ourselves?

To what extent should we align our image of the human being with technological progress? In order to address central questions such as this in a sensible manner, we should scrutinize concepts of our self-portrait such as consciousness, mind, self, thinking or freedom more carefully than we are accustomed to do in an everyday sense. Only then can we figure out where we are being led up the garden path, if someone were to claim, for instance, that there is really no such thing as free will or that the human mind (consciousness) is a kind of surface tension of the brain, as Francis Crick and Christof Koch at some point supposed: synchronized neural firing in the 40-Hertz range – a conjecture which they have since qualified.1

In contrast to the mainstream of contemporary philosophy of mind, the proposal introduced in this book is an antinaturalistic one. Naturalism2 proceeds on the basis that everything which really exists can ultimately be investigated in a purely naturalscientific manner, be it by physics alone or by the ensemble of the natural sciences. In addition, naturalism at the same time typically assumes that materialism is correct – i.e., the thesis that it is only material objects that really exist, only things which belong to a reality that is exhaustively composed of matter/energy. But what then is the status of consciousness, which until now has not been explained scientifically – and in the case of which it cannot even be foreseen how this is supposed to be at all possible?

Remarkably, the German word for the humanities is Geisteswissenschaften – that is, the sciences which deal with the mind in the sense of the invariant structure which is constituted via historically and culturally shifting self-conceptions. The point of dividing academic labor into the natural sciences and the mind sciences corresponds to the fact that it is hard to see how the Federal Republic of Germany, the worlds of Houellebecq’s novels, dreams about the deceased, thoughts and feelings in general, as well as the number π could really turn out to be material objects. Do they not exist, perhaps, or are they not real? Naturalists attempt to establish precisely the latter claim by clearing up the impression that there are immaterial realities, which according to them is deceptive. I will have more to say about this in what is to come.

As previously mentioned, I adopt the stance of antinaturalism, according to which not everything which exists can be investigated by the natural sciences. I thus contend that there are immaterial realities which I consider essential for any accessible insight of sound human understanding. When I consider someone a friend, and consequently have corresponding feelings for him and adjust my behavior accordingly, I do not suppose that the friendship between him and me is a material thing. I also do not consider myself to be only a material thing, although I would obviously not be who I am if I had no proper body, which in turn I could not have if the laws of nature of our universe had been very different or if biological evolution had taken another course. Antinaturalism does, therefore, not deny the obvious fact that there are necessary material conditions for the existence of many immaterial realities. The immaterial does not belong to another world. Rather, both the material and the immaterial can be parts of objects and processes such as the Brexit, Mahler’s symphonies, or my wish to finish this sentence while I am writing it.

The question of whether naturalism or antinaturalism is ultimately right is not merely important for the academic discipline of philosophy or simply for the academic division of labor between the natural sciences and the humanities, say. It concerns all of us, insofar as we are humans – that is, insofar as who we are in part depends on our self-conception. The philosophical question of naturalism vs. antinaturalism also plays an important historical role in our era of religious revival, since religion is quite rightly considered to be the bastion of the immaterial. If one overhastily ignores immaterial realities, one ends up not even being able to understand the rational core of the phenomenon of religion, since one views it from the start as a kind of superstition or cognitively empty ghost story. There are shortcomings in the idea that we could understand human subjectivity by way of scientific, technological and economic advances and bring them under our control by means of such an understanding. If we simply ignore this and pretend that naturalism in the form of futuristic science will solve all existential issues by showing that the mind is identical to the brain and that therefore nothing immaterial really exists, we will achieve the opposite of the process of enlightenment. For religion will simply retreat to the stance of irrational faith assigned to it by a misguided foundation of modernity. Modernity is ill-advised to define itself in terms of an all-encompassing science yet to come. In other words, as the case of scientology proves: we should not base our overall conception of who we are and how absolutely everything hangs together on science fiction. Science fiction is not science, even though it often enables actual science to make progress. But so does religion.

Already in the last century thinkers from different orientations pointed out the limitations of a misguided Enlightenment project based on the notion that we can extend scientific rationality to all spheres of human existence. For instance, the first generation of critical theorists, most notably Theodor W. Adorno (1903–1969) and Max Horkheimer (1895–1973) in their influential book Dialectic of Enlightenment, went so far as to claim that modernity was ultimately a misfortune that had to end in totalitarianism. I disagree. But I do believe that modernity will remain deficient for as long as it props up the fundamental materialist conviction that there are ultimately only particles dispersed in an enormous worldcontainer structured according to natural laws, in which only after billions of years organisms emerged for the first time, of which by now quite a few are conscious – which then poses the riddle as to how to fit the obviously immaterial reality of the mind into the assumption that it should not exist according to the materialist’s lights. We will never understand the human mind in this way! Arguably, this very insight led the ancient Greeks to the invention of philosophy, which at least holds for Plato and Aristotle, who both resisted naturalism with arguments still valid today.

To reclaim the standpoint of an antinaturalist philosophy of mind, we must give up the idea that we have to choose between a scientific and a religious image of the world, since both are fundamentally mistaken. There are today a group of critics of religion, poorly informed both historically and theologically, who are gathered together under the name of a “New Atheism,” among whom are counted prominent thinkers such as Sam Harris (b. 1967), Richard Dawkins (b. 1941), Michel Onfray (b. 1959) and Daniel Dennett (b. 1942). These thinkers believe that it is necessary to choose between religion – that is, superstition – and science – that is, clinical, unvarnished truth. I have already rebutted at length the idea that our modern democratic societies have to stage a constitutive conflict of world images in Why the World Does Not Exist. My thesis there was that, in any case, there are no coherent world pictures, and that religion is no more identical to superstition than science is to enlightenment.3 Both science and religion fail insofar as they are supposed to provide us with complete world pictures, ways of making sense of absolutely everything that exists, or reality as a whole if you like. There simply is no such thing as reality as a whole.

Yet, even if I am right about this (as I still believe after several waves of criticism and polemics against my no-world-view), it still leaves open the question to be dealt with here of how to conceive of the relation between the mind and its non-mental natural environment. It is now a matter of developing an antinaturalist perspective vis-à-vis ourselves as conscious living beings, a perspective happy to join in the great traditions of self-knowledge that were developed in the history of ideas – and not just in the West. These traditions will not disappear because a small technological and economic elite profit from the progress of natural science and now believe that they must drive out ostensible and real religious superstitions and, along with them, expel mind from the human sciences. Truth is not limited to natural science; one also finds it in the social and human sciences, in art, in religion, and under the most mundane circumstances, such as when one notices that someone is sad without theorizing about her mental state in any more complicated, scientific manner.

The decade of the brain

The recent history of the idea that neuroscience is the leading discipline for our research into the self is noteworthy and telling. Usually, this political background story is not mentioned in the set-up of the metaphysical riddle of finding a place for mind in nature. In 1989, the United States Congress decided to begin a decade of research into the brain. On July 17, 1990, the then president, George H. W. Bush (that is, Bush senior), officially proclaimed the “Decade of the Brain.”4 Bush’s proclamation ends solemnly and grandiosely – as is customary in this genre: “Now, therefore, I, George Bush, President of the United States of America, do hereby proclaim the decade beginning January 1, 1990, as the Decade of the Brain. I call upon all public officials and the people of the United States to observe that decade with appropriate programs, ceremonies, and activities.” A decade later, a similar initiative in Germany, with the title “Dekade des menschlichen Gehirns” [“The Decade of the Human Brain”] was launched at the University of Bonn under the auspices of the governor of North Rhine-Westphalia, Wolfgang Clement.

It is irritating that the press release for this very initiative began with a statement that is not acceptable as it stands: “As recently as ten years ago the idea that it could ever be possible to see the brain as it thinks was pure speculation.”5 This statement implies that it is now supposed to be possible “to see the brain as it thinks,”6 which, however, looked at more closely, is quite an astounding assertion, since it is ultimately a preposterous idea that one could see an act of thinking. Acts of thinking are not visible. One can at best see areas of the brain (or images thereof) which one might consider to be necessary prerequisites for acts of thinking. Is the expression “to see the brain as it thinks” supposed to mean that one can literally see how the brain processes thoughts? Does that mean that now one no longer merely has or understands thoughts but can also see them in a single glance? Or is it just associated with the modest claim of seeing the brain at work, without already implying as a consequence that one can somehow literally see or even read thoughts?

As far as I know, George Bush senior is not a brain scientist (let alone a philosopher), which means that his declaration of a decade of the brain can at best be a political gesture performed in order to funnel more government resources into brain research. But what would need to happen for one to be able to “see” the brain as it thinks?

Neuroimaging techniques such as functional magnetic resonance imaging, to which the German declaration alludes with its claim, constitute progress in medicine. Unlike earlier attempts to understand the living brain, they are not invasive. Thus, we can visualize the living brain with computer-generated models (but not directly!) without serious medical interventions in the actual organ. However, in this case, medical progress is associated with a further promise, the promise to make thinking visible. And this promise cannot be honored. In the strict sense, it is quite absurd. That is to say, if one understands by “thinking” the conscious having of thoughts, much more is involved than brain processes that one could make visible by means of neuroimaging techniques. To be sure, one can make brain processes visible in a certain sense, but not thinking.

The two decades of the brain, which officially came to an end on December 31, 2010, were not intended to be restricted to medical progress but offered hope for progress in self-knowledge. In this context, neuroscience has for a while been charged with the task of serving as the lead discipline for the human being’s research into itself, since it is believed that human thinking, consciousness, the self, indeed our mind as such can be located in and identified with a spatio-temporally observable thing: the brain or central nervous system. This idea, which I criticize in this book and would like to refute, I call for brevity’s sake neurocentrism. With the rise of other superpowers, Eurocentrism – that is, the old colonialist view of Europe’s cultural superiority over the rest of the world – is no longer taken seriously. One must now fight against a new ideological monster, neurocentrism, which is no less a misguided fantasy of omnipotence (and, incidentally, not very scientific either). While Eurocentrism mistakenly thought that human thinking at its peak was bound to a continent (Europe) or a cardinal point (the West), neurocentrism now locates human thinking in the brain. This spurs the hope that, in this way, thinking can be better examined, by mapping it, as Barack Obama’s more recent initiative of a “Brain Activity Map” suggests. As if the brain was the continent of thinking such that we could literally draw a map with the structure of neuroimaging models on which we could locate, for instance, the (false) thought that naturalism is true.

The basic idea of neurocentrism is that to be a minded animal consists in nothing more than the presence of a suitable brain. In a nutshell, neurocentrism thus preaches: the self is a brain. To understand the meaning of “self,” “consciousness,” “will,” “freedom” or “mind,” neurocentrism advises us against turning to philosophy, religion or common sense and instead recommends investigating the brain with neuroscientific methods – preferably paired with evolutionary biology. I deny this and thus arrive at the critical main thesis of this book: the self is not a brain.

In what follows, I will take a look at some core concepts of our self-understanding as minded, such as consciousness, self-consciousness and the self. I will do so from an antinaturalistic perspective. In this context, I will sketch some of the absurd consequences and extreme views that came out of naturalism, such as epiphenomenalism – that is, the view that the mind does not causally interfere with anything which really happens. Along with taking stock of some conceptual bits and pieces of our mentalistic vocabulary, I will scrutinize the troublesome issue of free will. Are we free at all, or are there good reasons to doubt this and to conceive ourselves to be biological machines that are driven by the hunger for life and that really strive for nothing other than passing on our genes? I believe that we are in fact free and that this is connected to the fact that we are minded animals of the sort which necessarily work out conceptions of what this means in light of which people become who they are. We are creative thinkers, thinkers of thoughts which in turn change the thinkers. It really matters how you think of yourself, a fact well known to psychologists and to human subjects in general, as we constantly during our conscious life engage with the realm of thoughts about ourselves and others.

Mainstream philosophy of mind for quite a while has sought to provide a theoretical basis for neurocentrism. This seemed necessary given that neurocentrism cannot yet claim to be based on empirical results, as neuroscience is infinitely far away from having solved even “minor” problems, such as finding a physical/neural correlate for consciousness, not to mention finding a location in the brain which correlates with insight into some complicated quantum-mechanical truth or the concept of justice. It has participated, sometimes even enthusiastically, in the decade of the brain. Yet, in the course of the unfolding of mainstream philosophy of mind it has become apparent to many that it is anything but obvious that the self is a brain.

Many reflections and key results of the last two centuries of the philosophy of mind already speak against the basic idea of neurocentrism. I will thus also refer to long-dead thinkers, since in philosophy one should almost never assume that someone was wrong simply because they lived in the past. Plato’s philosophy of mind loses nothing through the circumstance that it emerged in ancient Athens – and thus, incidentally, in the context of an advanced culture to which we owe some of the most profound insights concerning ourselves. Of course, Plato was wrong if he believed that we had an immortal soul somehow invisibly governing the actions of the human body. However, if you actually carefully read Plato, let alone Aristotle, it is far from clear that he believed in what the British philosopher Gilbert Ryle famously derided as “the ghost in the machine.”

Homer, Sophocles, Shakespeare, Tom Stoppard or Elfriede Jelinek can teach us more about ourselves than neuroscience. Neuroscience attends to our brain or central nervous system and its mode of functioning. Without the brain there can be no mind. The brain is a necessary precondition for human mindedness. Without it we would not lead a conscious life but simply be dead and gone. But it is not identical with our conscious life. A necessary condition for human mindedness is nowhere near a sufficient condition. Having legs is a necessary condition for riding my bicycle. But it is not a sufficient one, since I have to master the art of riding a bicycle and must be present in the same place as my bicycle, and so forth. To believe that we completely understand our mind as soon as the brain is understood would be as though we believed that we would completely understand bicycle riding as soon as our knees are understood.

Let us call the idea that we are our brains the crude identity thesis. A major weakness of the crude identity thesis is that it immediately threatens to encapsulate us within our skull as minded, thinking, perceiving creatures. It becomes all too tempting to associate the thesis with the view that our entire mental life could be or even is a kind of illusion or hallucination. I have already criticized this thesis in Why the World Does Not Exist, under the heading of constructivism.7 This view, coupled with neurocentrism, supposes that our mental faculties can be entirely identified with regions of the brain whose function consists in constructing mental images of reality. We cannot disengage ourselves from these images in order to compare them with reality itself. Rainer Maria Rilke gets to the heart of this idea in his famous poem “The Panther”: “To him, there seem to be a thousand bars / and back behind those thousand bars no world.”8

A recent German radio series called Philosophie im Hirnscan [Philosophy in the Brain Scan] asked the question whether it is “not the human mind but rather the brain” that “governs decisions.” “Free will is demonstrably an illusion.”9 What is worse, it claimed that neuroscience finally provides support for a thesis allegedly held by Immanuel Kant, namely that we cannot know the world as it is in itself.10 The German philosopher of consciousness Thomas Metzinger (b. 1958), a prime representative of neurocentrism, is reported to claim that

Philosophy and neuroscience agree: perception does not reveal the world, but a model of the world. A tiny snippet, highly processed, adjusted to the needs of the organism. Even space and time, as well as cause and effect, are created by the brain. Nevertheless, there is a reality, of course. It cannot be directly experienced, but it can be isolated by considering it from various vantage points.11

Fortunately, many philosophers who work in epistemology and the theory of perception would not accept this statement today. The theory that we do not directly experience reality but can only isolate it by considering it from various vantage points proves on closer inspection to be incoherent. For one thing, it presupposes that one can directly experience a model of the world, as the quotation indicates. If one had to isolate this model itself indirectly by considering reality from various vantage points on one’s own, one would not even know that, on the one hand, there exists a model and, on the other, a world of which we construct internal models. To know that one constructs or even has to construct a model of reality implies knowing something about reality outright, such as that we can only know anything about it indirectly for some reason or other. Thus one does not always need models and is not trapped within them, so to speak. And why then, pray tell, does the model not belong to reality? Why should, for instance, my thought that it is raining in London, which indeed I do not first need to isolate by considering reality from various vantage points in order to have it, not belong to reality? If my thought that it is raining in London right now does not belong to reality (as I can know it without first having to construct a model of mental reality), then where exactly does it take place? With this in mind, new realism in philosophy claims that our thoughts are no less real than what we are thinking about, and thus that we can know reality directly and need not make do with mere models.12

My own view, New Realism, is a version of the idea that we can actually grasp reality as it is in itself by way of our mental faculties. We are not stuck in our brains and affected by an external world only via our nerve endings such that our mental life is basically a useful illusion, an interface or computational platform with a basic evolutionary survival value.

After the failures of the loudmouthed exaggerated promises of the decades of the brain, the Süddeutsche Zeitung, one of the biggest German newspapers, pithily reported:“The human being remains indecipherable.”13 It is thus time for a reconsideration of who or what the human mind really is. Against this background, in this book I sketch the outlines of a philosophy of mind for the twenty-first century.

Many people are interested in philosophical questions, in particular those pertaining to their own minds. Human beings care about what it means for them to be minded, suffering, enjoying, thinking and dreaming animals. Readers who are interested in philosophy but do not spend the whole day going through philosophical literature often have the reasonable impression that one can only understand a philosophical work if one has read countless other books first. In contrast, the present work should be accessible without such assumptions, insofar as it also provides information about the relevant basic ideas lurking in the background. Unfortunately, many generally accessible books about the human mind in our time either simply assume a naturalistic framework or are driven by the equally misguided idea that we have immortal souls on top of our bodies. My own stance is thoroughly antinaturalistic in that I do not believe that nature or the universe (or any other domain of inquiry or objects) is the sole domain there is. We do not have to fit everything into a single frame. This is an age-old metaphysical illusion. However, there is a further question concerning the structure of human mindedness, as the human mind certainly has neurobiological preconditions (no mind without a suitable brain) but also goes beyond these conditions by having a genuinely immaterial side which we will explore.

Can the mind be free in a brain scan?

My overall goal is the defense of a concept of the mind’s freedom. This includes the fact that we can deceive ourselves and be irrational. But it also includes the fact that we are able to discover many truths. Like any other science or discipline, philosophy formulates theories, gives reasons for them, appeals to facts that are supposed to be acceptable without further ado, and so forth. A theory consists of propositions – claims that can be true or false. No one is infallible, certainly not in the area of self-knowledge. Sophocles portrayed this harshly in Oedipus the King, but hopefully things will not unfold so tragically here.

My main targets in this book, neurocentrism and its pioneering precursors – the scientific image of the world, structuralism and poststructuralism – are all philosophical theories. Sometimes it seems as if the empirical findings of brain research entail that the self and the brain are identical. Advocates of what I critically call “neurocentrism” act as though they could appeal to scientific discoveries that should not be doubted by reasonable modern citizens and thus to alleged facts recognized by experts. Yet, with its sweeping assumptions, neurocentrism formulates genuinely philosophical claims, which here means claims that one cannot delegate to some other branch of learning. Science itself does not solve philosophy’s problems unaided by philosophy’s interpretation of its results. Neurocentrism is ultimately just bad philosophy trying to immunize itself against philosophical critique by claiming to be justified not by philosophy, but by actual neuroscientific discoveries. Notice, though, that no neuroscientific discovery, no fact about our neurobiological equipment without further interpretation, entails anything about human mindedness.

In particular, for its interpretation of neuroscientific knowledge, neurocentrism brings to bear philosophical concepts such as consciousness, cognition, representation, thinking, self, mind, free will, and so forth. Our understanding of those concepts by means of which we describe ourselves as minded animals is stamped by a millennia-long intellectual, cultural and linguistic history. There is no possibility for us simply to sidestep this fact and take, as it were, a neutral or fresh look at the human mind, as if from nowhere or from a God’s-eye point of view. Our ways of thinking about ourselves as thinkers are mediated by the language we speak and by the manifold cultural assumptions which govern our self-conception, as well as by a huge range of affective predispositions. Our self-conception as minded always also reflects our value system and our personal experience with mindedness. It has developed in complex ways, in the tension between our understanding of nature, literature, legal systems, values of justice, our arts, religions, socio-historical and personal experience. There just is no way to describe these developments in the language of neuroscience that would be superior or even equal to the vocabulary already at hand. Disciplines such as neurotheology or neuroaesthetics are “terrifying theory-golems,” as Thomas E. Schmidt sharply puts it in an article on new realism for Die Zeit.14 If a discipline only gains legitimacy by being able to observe the brain while the brain engages with a given topic or object, we would ultimately need a neuro-neuroscience. Whether we then would also still have to come up with a neuro-neuro-neuroscience, time will tell …

There is also a suspicious political motivation associated with neurocentrism. Is it really an accident that the decade of the brain was proclaimed by George H. W. Bush shortly after the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 and thus with the end of the Cold War looming? Is this just a matter of political support for medical research? Does the idea of being able to watch the brain – and thereby the citizen – while thinking not also imply a new possibility for controlling social surveillance (and the military-industrial complex)? It has long been well known that possibilities for controlling consumers are expected from a better understanding of the brain: think of neuro-economics, another theory-golem out there.

As the German neuroscientist Felix Hasler (b. 1965) plausibly argued in his book Neuromythology, the decade of the brain also goes along with various lobbying efforts. By now, more students at American research universities take psychotropic drugs than smoke cigarettes.15 The higher resolution and more detailed knowledge of our images of the brain promise to contribute to social transformation in the context of what the German sociologist Christoph Kucklick aptly summarizes as a “control-revolution.” He observes that we live in a “granular society,” where we are no longer merely exploited but are also put in a position to interpret ourselves as objects of medical knowledge.16 The crude identity thesis corresponds to the fantasy that our self, our entire human mind, turns out to be a physical object among others, no longer hidden from view.

The question, of who or what the ominous self really is, is thus revealed to be significant not merely for the discipline of philosophy but rather in political terms as well, and it concerns each one of us on an everyday level. Just think about the popular idea that love can be defined as a specific “neurococktail” or our bonding behavior be reduced to patterns trained in prehistoric times in which our evolutionary ancestors acquired now hard-wired circuits of chemical flows. In my opinion, these attempts are really relief fantasies, as they defer responsibility to an in itself irresponsible and nonpsychological machinery which runs the show of our lives behind our backs. It is quite burdensome to be free and to thus figure that others are free, too. It would be nice if we were relieved of decisions and if our life played out like a serenely beautiful film in our mind’s eye. As the American philosopher Stanley Cavell puts it: “Nothing is more human than the wish to deny one’s humanity.”17

I reject this wish, and in this book I argue for the idea that the concept of mind be brought into connection with a concept of freedom, as it is used in the political context. Freedom is not merely a very abstract word that we defend without knowing what we actually mean by it. It is not merely the freedom guaranteed by a market-based economy, the freedom of choice of consumers confronted with different products. On closer inspection, it turns out that human freedom is grounded in the fact that we are minded animals who cannot be completely understood in terms of any natural-scientific model or any combination of them, be it present or futuristic. Natural science will never figure us out, not just because the brain is too complex (which might be a sufficient ground to be skeptical about the big claims of neurocentrism), but also because the human mind is an open-ended process of creation of self-conceptions of itself. The core of the human mind, the capacity to create said images, is itself empty. Without the variation in self-images, no one is at home in our minds, as it were. We really exist in thought about ourselves, which does not mean that we are infallible or illusions.

And thus we come to the heart of the matter. We exist precisely in the process of reflecting on ourselves. This is the lot of our form of life. We are not merely conscious of many things in our environment, and we do not merely have conscious sensations and experiences (including feelings); rather, we even have consciousness of consciousness. In philosophy we call this self-consciousness, which has little to do with the everyday sense of a self-conscious person. Self-consciousness is consciousness of consciousness; it is the kind of state you are in right now as I instruct you to think about your own thought processes, to relate mentally to your own minds.

The concept of mental freedom that I develop in this book is connected to the so-called existentialism of Jean-Paul Sartre (1905–1980). In his philosophical and literary works, Sartre sketched an image of freedom whose origins lie in antiquity and whose traces are to be found in the French Enlightenment, in Immanuel Kant, in German Idealism (Johann Gottlieb Fichte, Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph Schelling, Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel), Karl Marx, Søren Kierkegaard, Friedrich Nietzsche, Sigmund Freud and beyond. In contemporary philosophy this tradition is carried on in the United States primarily on behalf of Kant and Hegel, although Kierkegaard and Nietzsche are also assigned a role. So far, Albert Camus and Sartre have played a minor role in the revival of the existentialist tradition in the philosophy of mind.

I mention these names only in order to remind us of an important strand of human thought about ourselves. The philosophical tenet I take over from that tradition I call neo-existentialism, which claims that human beings are free insofar as we must form an image of ourselves in order to be individuals. To have a human mind is to be in a position in which one constantly creates self-conceptions in light of which we exist. We project self-portraits of ourselves, who we are and who we want to be, as well as who we should be, and via our self-portraits we relate to norms, values, laws, institutions, and rules of various kinds. We have to interpret ourselves in order to have any idea of what to do. We thus inevitably develop values as reference points for our behavior.

Another decisive factor at this point is that we often project false and distorted self-images onto social reality and even make them politically effective. The human being is that being which forms an idea of how it is included in realities that go far beyond it. Hence, we project visions of society, images of the world, and even metaphysical belief-systems that are supposed to make everything which exists part of a gigantic panorama. As far as we know, we are the only animals who do this. In my view, however, it does not diminish other animals or elevate us morally in any sense over the rest of the animal kingdom which would justify the current destruction of the flora and fauna of our planet, the only home to creatures who are able to orient their actions in light of a conception of a reality that goes beyond them. It is not that we human beings should be triumphantly intoxicated on our freedom and should now, as masters of the planet, propose a toast to a successful Anthropocene, as the epoch of human terrestrial dominance is called today.

Many of the main findings arrived at by the philosophy of mind in the twentieth and twenty-first century to this point are still relatively little known to a wider public. One reason for this certainly lies in the fact that both the methods and the arguments that are employed in contemporary philosophy typically rest on complicated assumptions and are carried out in a quite refined specialized language. In this respect, philosophy is of course also a specialized discipline like psychology, botany, astrophysics, French studies or statistical social research. That is a good thing. Philosophy often works out detailed thought patterns about particular matters in a technical language out of sheer intellectual curiosity. This is an important training and discipline.

However, philosophy has the additional and almost equally important task of what Kant called “enlightenment,” which means that philosophy also plays a role in the public sphere. Given that all human beings in full possession of their mental powers constantly construct self-images which play out in social and political contexts, philosophy can teach everybody something about the very structure of that activity. Precisely because we are nowhere close to infallible with respect to our mindedness, we often create misguided self-conceptions and even support them financially, such as the erroneous but widespread conception that we are identical with our brains or that consciousness and free will are illusions.

Kant explicitly distinguishes between a “scholastic concept” [Schulbegriff] and a “cosmopolitan concept” [Weltbegriff]18 of philosophy. By this he meant that philosophers do not only exchange rigorous, logically proficient arguments and on this basis develop a specialized language. That is the “scholastic concept” of academic philosophy. Beyond this, in Kant’s view, we are obligated to provide the public with as extensive an insight as possible into the consequences of our reflections for our image of the human being. That is the “cosmopolitan concept” of philosophy. The two concepts go hand in hand, such that they can reciprocally critique each other. This corresponds to the fundamental idea of Kantian enlightenment – a role that philosophy already played in ancient Greece. The word “politics” itself, together with the set of concepts which still structure our overall relation to the public sphere, the polity, derives from ancient Greek philosophy. The idea made prominent by Plato’s Socrates is that philosophy, among other things, serves the function of critically investigating our self-conception as minded, rational animals. For many central concepts, including justice, morality, freedom, friendship, and so forth, have been forged in light of our capacity to create an image of ourselves as a guide to human action. Again, we can only act as human beings in light of an implicit or explicit account of what it is to be the kind of minded creature we happen to be. Given that I believe that neurocentrism is a distorted self-conception of the human mind, full of mistakes and based on bad philosophy, it is time to attack in the name of enlightenment.

The self as a USB stick

The Human Brain Project, which was endowed with more than a billion euros by the European Commission, has come under heavy criticism. Originally, its aim was to consolidate current knowledge of the human brain by producing computer-based models and simulations of it. The harmless idea was to accumulate all the knowledge there is about the brain, to store it and to make it readily available for future research.

Corresponding to the idea of medical progress based on knowledge acquisition are wildly exaggerated ideas of the capability of artificial intelligence which permeate the zeitgeist. In films such as Spike Jonze’s Her, Luc Besson’s Lucy, Wally Pfister’s Transcendence, Neill Blomkamp’s Chappie or Alex Garland’s Ex Machina, mind, brain and computer are confused so as to give rise to the illusion that we could somehow (and soon) upload our mental profiles on non-biological hardware in order to overcome the limitations of biologically realized mental life. In order to convince us that there is no harm in such fantasies, in Her we are shown a protagonist who falls in love with his apparently highly intelligent software, “who” happens to develop a personality with existential problems so that the program decides to break up with its human lover. In Transcendence, the protagonist becomes immortal and omnipotent by uploading his self onto a computer platform in order to disseminate himself on the internet. In Lucy, the female protagonist, after she is able consciously to control 100 percent of her brain activity under the influence of a new drug from Asia, succeeds in transferring herself onto a USB stick. She becomes immortal by transforming herself into a pure mass of data on a data carrier. This is a rampantly materialist form of pseudo-Buddhist fantasy represented by the idea that such a mind/ brain-changing drug has to come from Asia, of course …

Along with the imaginary relief that we get in wishing to identify our self with the grey matter in our skull, our wish for immortality and invulnerability also plays a decisive role in the current world picture. The internet is presented as a platform of imperishability, onto which one can someday upload one’s mind purified of the body in order to surf through infinite binary space forever as an information ghost.

Somewhat more soberly, the scientists of the Human Brain Project anticipate medical progress through a better understanding of the brain. At the same time, this project also proclaimed on its homepage, under the tab “Vision,” that an artificial neuroscience based on computer models, which no longer has to work with actual brains (which among other things resolves ethical problems), “has the potential to reveal the detailed mechanisms leading from genes to cells and circuits, and ultimately to cognition and behaviour – the biology that makes us human.”19

Scientific and technological progress are welcome, without question. It would be irrational to condemn actual progress merely on the ground that science over the last couple of hundred years has led to problems such as nuclear bombs, global warming, and ever more pervasive surveillance of citizens through data collection. We can only counter the problems caused by modern humanity with further progress directed by enhanced value systems based on the idea of an ethically acceptable sustainability of human life on earth. Whether we resolve them or whether humanity will obliterate itself sometime in the foreseeable future cannot be predicted. This depends on whether we will even recognize the problems and identify them adequately. It is in our hands to implement our insights into the threatened survival conditions of human animals. We underestimate many difficulties, such as, for instance, the overproduction of plastic or the devastating air pollution in China, which already afflicts hundreds of millions. Other problems are hardly understood at all at this point, such as, for example, the complex socioeconomic situation in the Middle East. These problems cannot be dealt with by outsourcing human self-conceptions to objective representations, maps and models of the brain. It is not only that we do not have enough time left to wait for neuroscience to translate everything we know about the human mind into a neurochemically respectable vocabulary. Rather, there is no need to do this, as we are already equipped to deal with the problems, but underfinanced and understaffed in the relevant fields of inquiry.

We certainly do not want to return to the Stone Age, indeed not even to technological conditions in the nineteenth century. A lamenting critique of modernity does not lead anywhere except for those who long for the end of civilization, which more likely than not reflects their own fears of civilization, their “discontent with civilization” (Freud).20 It is already almost unthinkable for us digital natives to write someone a letter via snail mail. If there were no email, how would we organize our workplace? As always, technological progress is accompanied by technophobia and the potential for ideological exploitation, which govern the debates over the digital revolution and the misuse, as well as the monitoring, of data on the internet.