Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: And Other Stories

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

In Case of Loss reveals Seiler's essays to be different to, but on a par with, his fiction and poetry. Beautifully anecdotal and associative, they throw a light on literature and his East German background, including the Soviet-era mining community he grew up in, and are full of insight, humanity and an attention to overlooked objects and lives.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 291

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

First published in English in 2023 by And Other StoriesSheffield – London – New Yorkwww.andotherstories.org

Originally published in German in the following books, for which copyright is as follows:Sonntags dachte ich an Gott, © Suhrkamp Verlag Frankfurt am Main 2004. Die Anrufung, © Lutz Seiler 2005Am Kap des guten Abends,©Insel Verlag Berlin 2018Laubsäge und Scheinbrücke, © Lutz Seiler 2020

For details of the source publications of the German texts of the essays and non-fiction pieces collected in In Case of Loss, please consult the Editorial Note after the texts.

All rights reserved by and controlled through Suhrkamp Verlag AG Berlin.

Translation copyright © Martyn Crucefix, 2023

All rights reserved. The rights of Lutz Seiler to be identified as the author of this work and of Martyn Crucefix to be identified as the translator of this work have been asserted.

Print ISBN: 9781913505783eBook ISBN: 9781913505790

Editor: Stefan Tobler; Copy-editor: Robina Pelham Burn; Proofreader: Madeleine Rogers; Typesetting and eBook by Tetragon, London; Series Cover Design: Elisa von Randow, Alles Blau Studio, Brazil, after a concept by And Other Stories; Author Photo: Heike Steinweg.

And Other Stories gratefully acknowledges that its work is supported using public funding by Arts Council England and the translation of this book was supported by a grant from the Goethe-Institut.

Contents

Under the Pine Vault Huchel and the Dummy Bridge ‘The post-war era never ends’: On Jürgen Becker In Case of Loss Aurora: An attempt to answer the question ‘Where is the poem going today?’ Illegal Exit, Gera (East) The Tired Territory Babelsberg: Brief Thoughts on Ernst Meister In the Anchor Jar Sundays I Thought of God The Flute Player The Invocation In the Movie Bunker The Soggy Hems of His Soviet Trousers: Image as a way into the narration of the past NotesEditorial NoteUnder the Pine Vault

1.

The house stands on the western edge of the village. The woods begin on a level with the house, the garden extending into the woods to be completely surrounded by the woods. Guests, stepping out of the house onto the terrace, exclaim, ‘Oh, there isn’t even a fence here.’ The fence is deep in the forest, invisible. Coming south down the narrow, paved road, you have the impression of heading straight towards the house, then the road changes direction. To begin with, I did not notice that the property lies in a depression. The snow lingers here for so long, even in a time of thaw, that it is hard to believe it is snow and you feel the need to step outside and check.

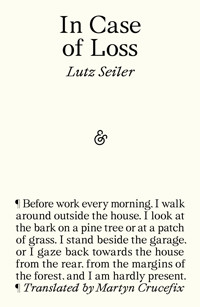

Before work every morning, I walk around outside the house. I look at the bark on a pine tree or at a patch of grass. I stand beside the garage, or I gaze back towards the house from the rear, from the margins of the forest, and I am hardly present. With its pointed roof and square base, the house resembles a pyramid. The tall pine trees stretch above it; they dominate it. When the wind blows, the branches beat on the roof beneath which we sleep. On those occasions, we do not get much rest and we lie there thinking it is about time the forest was taken in hand. The pine trees form a vault that seems to close over the house at night. Francis Ponge once described a pine forest as a ‘factory of dead wood’. The branches that wither on the tall trees, then break off, lie scattered like dark limbs about the garden. I collect them up and pile them in the corner of our woodland plot. For a long time, this was all the gardening I ever did.

Last winter, one of the branches that had blown off in a storm crashed through the roof of the bicycle shed which stands near the writing shed. In the writing shed are kept all those things that have not managed to find a place in the house: books, a suitcase of letters, photographs, discarded toys, a terrarium with two shrivelled-up blindworms, plus other bits and pieces, including a desk. On the shelves, there are manuscripts and, for reasons I have never really explained to myself, my notes from university lectures on topics such as ‘Aspects of Indus Culture’ or ‘History of the German-Italian Crusades’. I thought, perhaps, there would be something in them I might find useful. What that will be, only time can tell. Sometimes I stand there, in the shed, taking a look at something, though as if from a distance, the way I stand looking back at the house from the edge of the forest, or the way I stare at the bark of a tree. What is familiar enables me to absent myself. It is then things begin to come to mind.

2.

Beside the writing shed is the oldest of the three sheds, the ur-shed, the others being additions from later periods. The poet Peter Huchel used this as his cats’ quarters, but also for tools and for parts of his Sinn und Form journal archive, which included correspondence and submitted work. The cat flap in the shed door is broken. Apart from a few stray items, the archive vanished after the death of the poet Erich Arendt, who lived in this house on Hubertusweg after Huchel. It is said that Arendt never once set foot in Huchel’s tool shed. He was not a man much interested in tools and not especially drawn to the idea of life in a rural setting. But Huchel was, and this was, in part, to sustain a closeness to the materials and matters of village life, and it was from his memory of these things that much of his writing arose. In a radio programme in 1932, Huchel followed St Augustine in laying claim to that ‘great estate of memory, where heaven, earth and sea are present’. Huchel wrote in 1963 (in a letter of thanks to the West Berlin Academy, which had just awarded him the Fontane Prize) that the fact it turned out to be an estate in Brandenburg did not make it any less broad or limitless. Others, such as William Faulkner, Seamus Heaney and Les Murray, have also later moved back to the land which had already been cultivated in their writing. When Huchel bought the house and garden on Hubertusweg in the early 1950s, he had long sacralised the land, a process which, according to Joseph Campbell, is about recognising mythic symbols in the forms of the local landscape. Bertolt Brecht, who acted as real estate consultant on the purchase of the property, advised not paying any more than 6,000 marks for it. In the end, the purchase price was four times as much.

Firewood used to be cut in front of the shed: ‘Looking up from the chopping-block / under a light rain, / with axe in hand…’ The woodyard is bordered on the garden side by a couple of felled robinias, the so-called ‘sitting logs’, the best place to pass the time out of doors. Though a small table had been set up – nailed to a fallen acacia at the far end, closest to the forest – to let the poet work outside undisturbed, it is said he only rarely used it. At the time, the tool shed abutted another flimsy wooden shed and a sturdy fence behind which horses or sheep could be kept, something that was perhaps done in the pre-war years when the land still belonged to the novelist and scholar Bernhard Hoeft. But in Huchel’s time, the gate would stand wide open and the fenced area was used as a coal store. Last summer, my son found ‘black stones with writing on them’ as he was digging in the garden, and he proudly filled his rucksack with these treasures. Buried beneath the sand, from the era of the coal store, there are still coal briquettes bearing the fragmentary lettering of the REKORD brand.

3.

In 1993 we moved from Berlin to Wilhelmshorst, initially to a house at the other end of the village. I hardly knew anything of the circumstances in which Huchel had lived in Wilhelmshorst. The sandy soil on the paths around the house and the pine trees spoke of ‘the North’ to me. When we used to go on holiday from Thuringia to the Baltic Sea, the coastal region began for us in this area and beyond it lay the sea.

As an initial image of our new home, Cape Cod Evening by Edward Hopper seemed about right. Hopper owned a house in Truro, on the North American Atlantic coast. The picture, painted in 1939, shows a man sitting on the steps of a house and a woman standing beside him, leaning against the wall. A dog, in tall, browning grass, is looking for something the man has thrown, or perhaps has yet to throw. The gesture the man is making with his hand is not clear; perhaps he is just brushing the tips of the grass, while the woman, whose dress is dark like the forest beyond the house, is gazing towards the dog. The forest behind the house did not remind me of our forest, yet the image still reminded me of our new home, of a kind of easeful absence that I recognised in the man and that gesture he is making by reaching out his hand. That attentive, abstracted look, which can bring poems into being, turned ‘Cape Cod’ into ‘Cape Good’ and that became ‘good evening Cape’, the title of the first poem I wrote while living ‘out’ in Wilhelmshorst. In this unfamiliar Brandenburg landscape, among people who were strangers to me and who did not greet each other on the street, I was able to write in a way that I had never managed in the city. I felt at home from the very first day. My short poem ends, as the daylight is fading off the tops of the trees, with the strange utterance of a dog, or more precisely the shadow of a dog, standing at the gate, saying: ‘out here, I’m loved, you know, I’m loved’.

In Hopper’s work, the individual brushstrokes remain visible, though they subordinate themselves to the overall impact of the image and what it intends to convey. An ideal model for a poem: every one of the means used is to be taken to the limits of perceptibility, where it remains visible and invisible at the same time and, without imposing itself, contributes to the story the poem wants to tell.

4.

On 8 October 1995, I wrote in my notebook: ‘Broke into Huchel.’ There had been difficulties with the local housing authorities, who worked from a couple of dilapidated buildings on the outskirts of Beelitz and had refused to hand over the keys to the house. Beside the house, in the sand, lay a corrugated-iron sheet. Beneath this was the opening to the coal bunker through which we gained access to the cellar and from there into a bathroom with flower-patterned tiles. A dead pine marten lay in the basement bathtub covered in coal dust. Peter Huchel’s widow, Monica Huchel, who had, from a distance, instigated and legitimised this break-in, later explained over the phone how to work the National Boiler in the basement: a cast-iron marvel that not only required coal but coke as well, for which coal merchants in the 1950s had to be bribed. Back then, under cover of darkness, the black consignments would be dropped at the gate or lugged to the coal-hole: ‘from their filthy baskets they pour / the lumpen black grief / of earth into my cellar’. Huchel called verses like this ‘occasional poems’ in the Goethean sense. He wrote directly from the things that surrounded him. These were the objects of the house, the garden, the everyday and, above all, the landscape. There is no doubt, the poems go far beyond the visible and the concrete but, for their author, it remained important that they were firmly ‘of the earth’.

Before we broke open the front door from the inside, I wandered round the locked house for a while. The bathroom was the former laundry room for the ‘maid’, who until 1957 lived in a room between the kitchen and the dining room. Wastewater and sewage were pumped from the cellar out along a pipe into the pines. The cellar stairs led up to the kitchen and, from there, a small hallway led into the ‘vestibule’, as Monica Huchel called the hallway. From this vestibule, doors led off into the dining room and the ‘editorial office’, and from the centre of it the large, dark-stained staircase swept upwards. Also in the vestibule stood the ‘classics shelf’, in front of which Huchel once had his picture taken. In the photograph, you can see editions of the works of Chekhov, Schiller and Hauptmann, and, above them, sits a volume by Hermann Brockhaus which has holes in its spine; in its previous location, in Berlin, it had been damaged by shrapnel.

It actually felt colder inside the house than out, my breath condensing. I was sure there would be too many voices in this place. Too many, at any rate, for someone who tends to talk to himself, to the room at large, while engaged in writing. As I listened to the sound of my own footsteps through the vacant rooms, I was sure I ought to be treading and speaking more softly. As if the sound coming off the linoleum nailed onto the floorboards would be enough to dislodge from the walls the voices of previous inhabitants. Though that is not exactly what I wrote in my notebook on that first inspection of the house. There it says simply: ‘replace heating, refurbish doors, wiring, windows, etc’.

5.

The garden – basically a clearing covered with forest grass, hemmed in and half roofed over by the surrounding pine trees – has a remarkable feature that only became visible to us in the spring, when we had already been living in the house on Hubertusweg for six months. In the back third of the garden, close to the forest, along with the new growth of tall grass, geometrical outlines emerged from the ground: smaller and larger square shapes and others that were completed on one side with a semicircle. Viewed from the house, these outlines, gently swaying in the breeze, appeared to hover above the ground among the pale green tips of the new forest grass. The idea of an overgrown, abandoned graveyard (like one we had passed in a neighbouring village), now only preserved in the sketchwork of the vegetation, was reinforced when we walked among the outlines in the grass. In places, beneath the soles of our feet, we thought we could trace the firmer edges of graves in the soft forest floor. Even when I started in with a spade and began to uncover an edging of old Brandenburg bricks, I was still reluctant to accept what could hardly now be denied. My archaeological research had brought to light not graves, but pre-war flower beds. I consoled myself with the thought that T. S. Eliot must have already sensed the remarkable similarities between flower beds and graves when, in The Waste Land, he asks if the corpse that had been buried the previous year has begun to bud: ‘Will it bloom this year?’ However, despite resolving the mystery, something of the idea remained floating over the outlines preserved in the grasses. Since then, at any rate, this back third of the garden has been for me the kind of place Eliot might have had in mind in ‘The Burial of the Dead’. As some people visit cemeteries to reflect, to stop a moment, to connect with the past, or simply go in search of peace and quiet, whenever I feel so inclined, I walk among these outlines. Sometimes I squat down in one of the softly overgrown squares and look up into the ancient crowns of the pine forest. It is as if I, myself, had sprouted in that place and possessed some deep connection to the earth like the grass which, while I crouch down, comes up to my ears. No one sees me; the clearing is closed off on all sides.

6.

The clearing is a space: of creatures, of noises, of deceleration, a dwelling place in the open air. Sounds come from the two railway lines that run nearby. At night, you hear the clanking of freight wagons and the thump-thump of the rails on their sleepers. In the morning, the birds’ terrorising in the trees. From where we sleep, under the roof tiles, we can hear the beating of pigeons’ wings. In the morning, as the dew rises, voices come from the moraines: skinny guys playing football with their dogs’ chewed-up rubber balls. At 10 a.m. an out-of-work neighbour starts cutting timber: the muffled thumping of his axe reaches beneath the house. Then noises from the tennis court a few hundred metres away, beyond a stretch of woods: the serves, the brief calls, the pleasant plopping of the rallies. At any time of day: the singsong of a circular saw, rhythmic, quick; firewood being trimmed to stove length. Apart from keeping dogs, this is the favourite pastime of people living round here. As well as their gas or oil heating, there is hardly anyone who does not still have their old stove, for economic reasons partly, but more than that: who knows what the future holds? Also familiar is a prolonged, steady thrumming until one of the small, single-engine aircraft appears over the treetops, on clear days towing gliders into the air from the nearby airfield. From the ‘gliders hill’, near Saarmund, a bald-headed terminal moraine, the brave can achieve lift-off in the oldest fashion, hurling themselves down the incline. In the 1980s, when one of these would-be Otto Lilienthals had managed to reach West Berlin, twenty kilometres away, the moraine hill was swiftly cordoned off.

7.

At the end of spring, when the forest grasses begin to mature and they bow and blend into waves that begin to brown in the sunshine, the outlines of my grave beds disappear. They were laid out in the very early days: ‘Villa Hoeft’ and ‘1923’, the year the house was constructed, are inscribed on a small marble plaque to the left of the front door. In 1984, Arendt died in one of the smaller upstairs rooms, which had been a children’s room, then it was a study, then a death room and now it is being used as a children’s room again. After Arendt’s death, during the renovation of the house, the crumbling ‘Schönbrunn Palace’ yellow of the facade, which at the rear of the house was overgrown with ivy, was removed and the original marble plaque was hidden beneath the new render. Not much is known about Dr Bernhard Hoeft, whose year of death is recorded as 1945 though even the circumstances of his dying remain unclear. He was an academic in Berlin and wrote novels with such titles as There Went a Sower and Father and Son. In retirement, he devoted himself entirely to his passion, namely Leopold von Ranke. Hoeft’s estate, now kept in the Prussian Privy State Archives, consists of a number of boxes filled with thousands of handwritten pages, all of them Hoeft’s copying out of minutes of meetings, doctoral vivas and correspondence featuring Ranke: ‘Concerning the Magna Carta, the Cd. likewise supplied good answers; less satisfactory were his replies on the English Revolution…’ – for a moment on 25 February 1847 it seemed the candidate, Theodor Neumann from Görlitz, might not pass, but Ranke and the faculty extended their mercy. One of the boxes contains copies of letters variously to Mrs Klara Ranke, to the publishing house Hoffmann und Campe and even to King Friedrich Wilhelm IV, to whom Ranke, ‘in deepest devotion’, presented the third volume of his History of France. Apart from a few tiny exclamation marks in the margins and an inscrutable system of pencil crosses, Hoeft himself remains invisible in these pages. His handwriting is controlled, compact, orderly. However, the excessive copying of all this material with the least connection to Ranke’s affairs was not without its impact on Dr Hoeft’s own writing style. The last of his books, on Ranke’s Appointment to Munich, begins with a graceful: ‘It was not, really, in the least surprising that…’ This was published in 1940. In 1945, the Red Army rolls into Wilhelmshorst with a couple of tanks, one from each direction. The Willmann dairy is hit and has to be demolished. The victorious forces establish an ammunition depot on the central Goetheplatz. What would become known as the Huchel House, the comparatively remote ‘Villa Hoeft’, becomes the officers’ HQ. All trace of Hoeft himself disappears at this point. Even his daughter cannot provide information as to her father’s whereabouts; her mother never spoke of it, nor about why, very soon after, the house was auctioned off to become the property of the local savings bank. After the occupying forces move in, the daughter, then a fifteen-year-old girl, spends several days beneath the rabbit hutch of a neighbouring house. The Russian commander known as Curly Johnny, or ‘Syphilis for All’, is roaming the pine woods beyond the house and on the lookout for women in hiding.

8.

Rain soothes the forest, and the forest soothes the house. The dampened woods grow softer, heavier. The rain stirs a growing murmur in the vaulting pines, a sound that envelops us while, up above, the breeze passes. Every year the dampness pushes a few exotic growths up through the moss and the rippling forest grass: the grave beds open up. Tufts of seeded alyssum, blue poppies and two rhubarb stems spring up – the old, overgrown beds make a show of what they still harbour. Snails congregate on the rhubarb stems and around strawberry plants. The strawberries are vestiges of a later, smaller-scale cultivation from the time of the poet Arendt, something his young wife is said to have established in the year before his death. I had once before noticed how snails are associated with graves in a cemetery in the west of Ireland, at the foot of Mount Brandon. In the pouring rain, we visited a coastal graveyard behind the village of Fahamore. As with every plot of ground there, the cemetery is enclosed by a stone wall, beyond which, in this case, the rolling surf began immediately. There were recent graves and older, dilapidated tombs, caved in, revealing a glimpse of bones. The rain eased off, but a stiff wind blew up, so the children had to cling on to the tall, narrow gravestones. As I was wandering around, I spotted a few black snails in the grass, a rare cluster, or so I thought. Then I looked more closely and saw the grass was overrun with processions of snails crawling out of the gaping tombs. Evidently, the weather suited them, or perhaps it gave them an opportunity to wash, to mate, to get some fresh air, or simply to relocate from an older to a more recent grave. Then gulls began to circle over the cemetery and we headed off.

Even sheltered beneath the vault of the pines, the snails are at the mercy of the birds. There are birds that move with such speed between the trees you wonder how they manage not to collide with them. Their shadowy flight seems to set the foliage in motion. Suddenly they appear in the clearing: first, a soft, almost inaudible rustling of flight, then the shadow of a small, fist-sized body in the air, and, before you actually glimpse them, they have already vanished into the far side of the wood. In the garden, if no one disturbs them, they use the brick surface of the terrace to break open the snails’ shells. They hurl them from their beaks onto the bricks until they shatter or gape wide enough for them to extract the soft body from its socket. Flies and ants mop up the sticky remains. When we sit outside in the evening, the shards of snail shells crunch under our feet.

Before the war, people would sit to the side of the house, beneath a huge pine tree. A bench and a table, large enough for meals, are said to have stood there. But since that time, the forest has washed over the spot and advanced right up to the house. Hardly any of the old trees remain unscathed: galvanised hooks, a pulley with a porcelain insert for a washing line, a white scar in the beech bark where it will not close over a nail. In amongst it all can be found the scribbling of insects, the thin, clear lines on the inside of fragments of bark that we read the moment they drop from dead trees into the undergrowth, where they add to the land register of this forest plot.

9.

Perhaps Hoeft, the Ranke researcher, also provided drawings for the layout of his house. If so, it is ‘not, really, in the least surprising’ that the interior and exterior, as well as the individual rooms, do not properly fit together. More confusion arises as a result of the various partition walls installed after the time of the officers’ HQ which created additional rooms for the accommodation of relocated people. Each room is misshapen, full of corners and alcoves. A load-bearing wall runs towards a window, swerves at the last moment and an alcove emerges in which the radio had its place in Huchel’s time. In front of it, there are two armchairs and a small table, the top of which is made of ceramic tiles. Here, on the upper floor, beside the radio, Huchel would gather with his guests for cognac and coffee after dinner. It was a sort of smoking room, although smoking was pursued throughout the house, regardless of location. Cigarettes always had to be available and, if they ran out, one of the children would take the train through the woods to Wannsee to buy a new pack of Gold Dollar. The photographer Roger Melis’s images have recorded and preserved the radio’s position and some of the guests too: Huchel with Böll, Huchel with Frisch, Huchel with Kundera, etc. Huchel later suspected that there were ‘bugs’ in the ceiling and in the telephone. To make surveillance more difficult, the radio was turned on during conversations.

‘Today I remember the dead in my house’. So begins a marvellous elegy by Octavio Paz that speaks of the dead, but also of time running out:

Between door and death there’s little space

and hardly time enough to sit,

to lift your head, to look at the clock

and to discover: a quarter past eight.

Bearing witness to things handed down from the past, and to the house itself, is an ambivalent business. Which of us wants to be continually reminded of the past, or to be made so aware that the time we are given will vanish in a moment: ‘a quarter past eight’? Perhaps, as a glance at the history of the genre suggests, it is the kind of people who engage in the writing of poetry. In a house that has itself become a kind of ancestral shrine to literature, you find yourself talking to the dead whose work is already integral to any such conversation. This leads to a strange sort of interference. Paz’s poem states:

Your silence is the mirror of my life,

in my life your dying persists:

I am the last error in your erring.

The ‘last error’? Should there be some sort of comfort to be found in that? Perhaps, in the end, you might prefer to ‘pass away’ in the proper sense of the phrase and be the ‘last’. Then, suddenly, it is ‘a quarter past eight’ and the door has closed. And the party goes on noisily in some other room.

10.

‘Why, Antaeus, this place, all day long / speaking through the forks of branches?’ begins a poem I started, and later abandoned, about living under the pine vault. Since the renovation work on the house, the roof has been broken up by a row of windows. Under them stands the desk; you sit there, in the topmost third of the forest.

The movement of the treetops before your eyes is dizzying and the house starts to sway. During storms, the timber joints crack ominously, and you say to yourself: the roof-tree is buckling. When it rains, we sit here as if under canvas, in a place of shelter, yet everything is enveloped in the noise of the downpour. In among the oaks that face the road, the rain falls more noisily than in the pines – the pines hold steady beneath the downpour. In summer, when the weather is better, the quality of light in the branches shifts endlessly. Light falls through budding leaves in a palimpsest that towers over us and around us, slowly shifting with the sun through the course of the day. In the evening, the lit-up flanks of the trees show a dark yellow colour, of the kind you might find in a painting by Bonnard. Later still, the tops of the pines redden and, in the last moments (so briefly you are not sure if you imagined it), they glow blood-red, then are dark to their very tips.

Huchel wrote in a room under this same roof. At midday, the poet would come down the ‘decrepit stairs’, as he says in the poem ‘Hubertusweg’, and mutter lines to himself at the table, lines his wife immediately wrote down and then turned into typescript. With this draft, the master disappeared back up to his room for the afternoon. With more completed drafts, he would continue on down to the editorial office, located on the ground floor. There he would dictate the text to his secretary, Frau Narr, who, as Huchel’s editorial colleague from Potsdam Fritz Erpel reports, even insisted on using the Duden dictionary’s spelling for poems. When Huchel worked in the editorial office on Sinn und Form, he would jot down lines of poetry or individual words on scraps of paper. When visitors arrived, these scraps – that had over time become scattered here and there – had to be gathered up for safekeeping. In the post-war period, Huchel was upset when he discovered lines and images from his poems had been plagiarised in a book by Karl Krolow. The theft came from poems that had already been published, at the start of the 1930s, in Die literarische Welt and the magazine Die Kolonne. Since that period, Huchel had been known as a poet, even though his first collection – called simply Poems (Gedichte) – did not make an appearance until 1948, when he was already forty-six years old.

Opposite the writing room is the so-called ‘eye’, a small window, arched over by a gentle curve of the roof and hence slightly rounded at the top; through it, you look down onto the front of the property. Quite hidden, you can see who is passing, who stops, or who is at the gate. When I climb the steep, ‘decrepit’ stairs up to the attic, there is a stone that can be seen through the eye window – though only from a particular spot, on the last but one step – an erratic that Huchel had picked out on a walk as his gravestone and brought back into the garden. Then the view framed by the tiny window reminds me of Robert Frost’s poem ‘Home Burial’: ‘The little graveyard where my people are! / So small the window frames the whole of it. / Not so much larger than a bedroom, is it?’ Anyone who reads Frost’s ‘pastoral’, along with Joseph Brodsky’s commentary on it, will learn just about everything there is to know about movement, dramatic impact and the handling of perspective within a poem. And although there are frequent references to the characteristically American in Frost’s poetry, his book, North of Boston, does not seem to me to be far removed from this locality.

To the right of the erratic, on the right-hand edge of the picture framed by the eye, lies the manhole cover over the water meter; to the left is the gate and the driveway. In the middle of the picture, at the front of the house, stands the column of a single pine tree like the big hand of a clock, at an angle, a little after the hour. At midday and then again in the evening, bells automatically ring out from the little church on the Goetheplatz, built during the Nazi era. At the ringing of the bells, the dogs also strike up. First, there is a single, short burst from across the street, or perhaps one street further over, then neighbouring dogs follow suit; finally, a great chorus envelops the village which might as well be coming from a pack of wolves. It is said the wolves are set to return to the woods in this area. They are following the exact same routes as their ancestors. But not much really happens in ‘the eye’. Twice a day, sometimes as early as eight o’clock in the morning, a dog-owning couple pass, walking their two white poodles. Then, at noon, the post arrives. In the evening, the lights come on along the street, the twilight shift.

11.

Once, perhaps, there really was something about this place that lay beyond time and its events, in other words – ‘outside’. ‘Out in the woods of Wilhelmshorst, never travelling and seemingly immoveable,’ writes Hans Mayer of Huchel, he was still ‘a decade ahead of his far busier literary contemporaries.’ The apparent contradiction between being ‘ahead’ and being ‘on the outside’ brings to mind a marvellous observation made by Hermann Lenz: ‘Whoever stands still, leaps far ahead in time.’ While Mayer’s remark recalls the timeline we used to have at school, with its implied obligation to make progress, in Lenz’s comment you can also see the possibility of taking your time, while standing still, time to consider your own direction of travel. ‘The transformations of the self are the essence of time,’ wrote Günter Eich in his Remarks on Poetry (Bemerkungen uber Lyrik) in 1932, and he went on: ‘The transformations of the self are the business of the lyric poet.’ Even if later Eich did not foreground such ideas, they nevertheless appear, towards the end of the 1950s, as the basis of what he calls ‘the anarchist’s instinctive feeling of resentment’. Eich, too, had tried to settle ‘outside’. Of course, this ‘outside’ had nothing to do with ‘escaping the world’, nothing to do with an idyll beyond the metropolitan. The poet friends Huchel, Eich and Martin Raschke had distanced themselves from the late Expressionist mainstream and the New Objectivity and also from the presumed association of modernity with the city. But not out of any traditionalism. Eich was a technophile and had a passion for cars; Huchel and Eich were among the first to make use of the new medium of radio for their work. Conscious of the formal possibilities, they were concerned with a modernity without the obvious trappings of modernism used by other new poets who wanted to prove themselves as being ‘on the cutting edge’.