Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

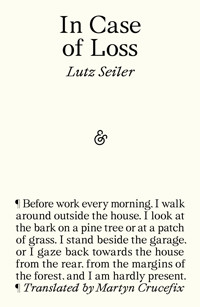

- Herausgeber: And Other Stories

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

- Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

November 1989. The Berlin Wall has just fallen when the East German couple Inge und Walter set out for life in the West. Their son Carl heads to Berlin where he discovers anarchy, love and poetry. Musical and incantatory, Seiler's novel Star 111 tells of the search for authentic existence and also of a family which must find its way back together.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 740

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

First published in English in 2023 by And Other StoriesSheffield – London – New Yorkwww.andotherstories.org

Copyright © Suhrkamp Verlag Berlin 2020. Originally published in German as Stern 111 in 2020.All rights reserved by and controlled through Suhrkamp Verlag Berlin.

Translation and afterword copyright © Tess Lewis, 2023

All rights reserved. The rights of Lutz Seiler to be identified as the author of this work and of Tess Lewis to be identified as the translator of this work have been asserted.

ISBN: 9781913505745eBook ISBN: 9781913505752

Editor: Stefan Tobler; Copy-editor: Robina Pelham Burn; Proofreader: Madeleine Rogers; Typesetter: Tetragon, London; Series Cover Design: Elisa von Randow, Alles Blau Studio, Brazil, after a concept by And Other Stories; Author Photo: Andreas Münstermann.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

And Other Stories gratefully acknowledge that our work is supported using public funding by Arts Council England and that the translation of this book was supported by grants from the Goethe-Institut and English PEN’s PEN Translates programme, which is supported by Arts Council England.

For my parents

I am twenty-eight, and practically nothing has happened.

Rainer Maria RilkeThe Notebooks of Malte Laurids Brigge

The Cable Address

Carl’s train stopped well before the station, accompanied by a metallic stuttering and juddering as if his journey’s heart had suddenly stopped beating just before arrival. Outside, a sea of crisscrossing tracks and behind them, the Wailing Wall. The Wailing Wall was a kilometer-long brick facade that demarcated the Leipzig station grounds from the city, pierced by strange, honeycomb-like openings through which a street, buildings, and sometimes even people were visible. For some reason, it was not uncommon for trains to stop here, outside the station, the destination in view, for minutes or hours; it was like an old complaint, a familiar song. The travelers’ gaze inevitably fell on this wall—hence the name.

The morning after the telegram arrived, Carl had set out for Gera. He wore a clean pair of jeans and his old black motorcycle jacket with the diagonal zipper across the chest over a freshly washed shirt. He owned three of these collarless work shirts, identical shirts with thin, pale blue stripes from his time as an apprentice bricklayer before he began his studies. He’d even trimmed his hair a bit, laboriously, with dull nail scissors—shoulder-length would have to do. He was returning home like someone long-lost, at least that’s how he saw it for a moment. Most castaways were stranded only after their return—that’s the saddest part of those stories. Once home, they could not adapt to life on the mainland. The many obstacles, storms, years—all the loneliness, which, ultimately, turned out to have been best. Often, they were unable to tolerate mainland food or they died because of their excessively long hair, which they had to display at local fairs to make money, and which, one night, when they were asleep, would wrap itself around their necks like a noose …

Outside, the conductor walked the length of the train, swearing and knocking on the windows of each car: “Off the train, everyone off!”

They were on an old outer track with a temporary wooden platform. Technically, it was not a platform, but a ramp through which grass grew and a few young birch trees protruded sideways, apparently impervious to waste oil and excrement. The birch leaves glowed yellow. Carl saw this glow and heard the rap of his steps on the wooden ramp. Like convicts, they trudged single file toward the station on a narrow walkway between the tracks.

The dimly lit concourse surged with people, a billowing motion, shouting and braying. Again and again, the loudspeakers, which transformed every word into a muffled, hollow dream language, a single, completely incomprehensible call, repeated: “Uh-uck!”

The object of their siege was the express train to Berlin, a string of eight or nine grime-encrusted carriages with nicotine-yellow windowpanes. On the evening news the day before, there had been talk of additional trains and further provisional border crossings, along with repeated formulaic appeals for calm. A few of the Berlin-bound managed to scale the greasy carriages and launch themselves headfirst into the overcrowded compartments through the skylights. A scene out of Bombay or Calcutta—in the Leipzig train station it appeared excessive, like part of an overblown choreography, out of place and on a large scale.

Carl slowly pushed his way through the crowd. His bag kept getting caught. The strap cut into his shoulder and seemed about to tear. He immediately regretted having dragged all his papers and books along—how stupid, how thoughtless of him. Several expletives rang out, his face was pressed into the coarse felt of a jacket that promptly made a feral sound—then something rammed him in the chest. He fell, dragged down and twisted by the weight of his bag. Someone who surely was just trying to catch him hit Carl’s face hard with the flat of his hand; Carl tasted sweat and lost his bearings.

“Uh-uck! Uh-uck!”

The cry now came from on high. It was the voice of a drunken giant babbling down at them from the soot-blackened cathedral of the station, but his dwarves no longer obeyed.

“My bag!” Carl shouted when he came to.

“Which bag, young man? Do you mean this one?”

The bag was still there; more precisely, he was lying on it. For a moment Carl saw nothing but faces bending over him, tense but controlled. It’s joy, Carl thought, pure joy. But he couldn’t actually tell what emotion was controlling them, if it was, in fact, still joy or already hatred.

“Do you need help?”

A girl, sixteen at most, was offering him a handkerchief. As always, Carl was surprised by the gleaming red, that fresh, slightly unctuous substance that couldn’t possibly have come from him: blood.

“Will you be alright?” The girl touched Carl’s arm. He saw her round face and in it, her eyes, very light and watery, as if blind.

“No, you have to stay with me. Forever.”

“Thanks. You’ll survive.”

He made his way outside along an empty platform. He tried not to pay too much attention to the blind girl (she wasn’t actually blind), but she stayed with him, holding his arm. They were a couple, at least until Carl collapsed onto a bench.

“Are you also going to Berlin?”

Carl tilted his head back and felt it in his throat—a warm thread that unspooled from somewhere on the roof of his mouth and, strangely enough, burned a little. He had to swallow, again and again, but it still hung there. Since he was a child, he often had nosebleeds. Back when these things mattered, he used to impress his friends by being able to stop the bleeding with a single blow of his fist to his forehead. It was a boxing trick. He rammed the ball of his hand against his forehead, or the blow glanced off it. The impact had to be forceful, making the head jerk backward. It was all in the jolt. If you were too timid it didn’t work.

“No, I’m going …” He shook his head gingerly to stop the spinning before his eyes. The girl remained standing next to him for a while. Carl considered what he could ask her but then, suddenly, she was gone, and he murmured his answer: “Home. I’m going home.”

Centimeter by centimeter, the express train to Berlin pulled away from the platform. The overcrowded carriages slid past. Someone hollered, “Arrivederci, you bum!” and a spontaneous chorus struck up the song that Carl only knew in his grandmother’s melancholy rendition: “I’d love to stay a bit longer …” Carl watched the train leave. The departing chorus passed the ramp with the glowing birch trees, which began waving shyly and tremulously.

The word bum was still buzzing in his skull. A bum was someone with a bloody nose, squatting on a train platform that no trains left from. Someone who has no idea where the journey is headed, thought Carl.

He pulled the telegram from his bag. It was just a note, handwritten, with a stamp below the writing. In the lower right-hand corner, the operator had noted the date and time: 10 November, 9:20 a.m. “we need help please do come immediately your parents.” No reproach, no mention of his months of silence, only this, a cry for help. Just that weak little word do. Carl could hear it, in his mother’s voice: “do come.” He pictured her hurrying downhill into town, with short, brisk steps, he pictured her dictating the address, filling out the telegram form, meticulous but also tense, nervous, which is why she forgot the salutation, and he pictured Mrs. Bethmann, the woman at the counter, counting the syllables. Even these days, when the most unimaginable things were happening, the “cable address”—as those behind the post office counter called it—still worked.

Carl had to admit that he hadn’t been particularly worried—parents were solid ground, unassailable, the home turf you could retreat to in times of need. Missed, yes, it was odd, he missed his parents and not just this past year when he’d only seen them one single time, no, even before then, always, actually, he had always, always missed them.

He looked for the track on which the southbound trains usually ran, to the region on the border between Thuringia and Saxony from which his family came—“where the fox and the hare bid each other goodnight,” his father’s favorite expression for “in the middle of nowhere.” When he was a child, every night before he went to sleep, Carl had imagined foxes and hares slowly gathering at the forest’s edge to say goodnight. Sometimes there were other animals in the mix, all different kinds of animals, and sometimes a few humans who were good friends of the animals. All these gentle, clever creatures gathered in one particular, moonlit spot at the end of the day—a silhouette of raised muzzles, raised heads and a single chorus: “Goodnight, you hares from Gera, you foxes from Altenburg, you ravens from Meuselwitz, goodnight!”

Part I

Bewilderment

Carl couldn’t remember who’d first suggested “going out for a few steps,” his father or his mother. It wasn’t unusual. He followed behind, his parents in front, as always. His father had just turned fifty, his mother forty-nine. His father had become slender, the brown leather jacket, the drooping shoulders, gray hair thinning on the back of his head—Carl had never seen him this way. They walked along the Elsterdamm from Langenberg to the Franzosen Bridge, their traditional walk along the river. There were hundreds of photographs of it in the family album, neatly glued and meticulously captioned by his mother: the six-year-old in a collared shirt and bow tie, his eager smile and large, eager teeth—Carl on his first day of school. Then the fourteen-year-old with a pageboy haircut and a serious, dismissive air. Next to him, his mother, her hair in a chignon, wearing a Corfam coat, autumn ’77. And so on, along the timeline through all the years and seasons until today, which no one photographed. On their right, the lazy flow of the Elster, its moldy bank and the Langenberg meadows. His father stopped, turned and said, “Carl.”

It would be nice to relate that a wind suddenly rose in the Elster Valley, blowing along the river, or that there was a peculiar sound, maybe a kind of whistling, a thin, soft whistle from the meadows that is heard only once every fifty or one hundred years: “Carl …”

His parents wanted to go. To leave the country, in short.

A soft whistling, for example. Carl looked around and it was suddenly as if this (their) world of river and path had only been set up provisionally (not for eternity) and as if it now (like everything else) (obviously) had to be dismantled and stashed away, as if it had (from one moment to the next) become irrelevant and worthless. “That’s not how we meant it,” Carl’s mother would have interjected if there had been the opportunity but there was no pause in the sequence, just bewilderment. Carl’s single sentence, bumbling, stammering, like that of a helpless, frightened child whose parents are suddenly no longer adults: “I think you’re underrating the whole, the whole—I mean, the whole homeland thing.” It was strange for him to say it, he wasn’t used to talking to his parents like this; something had been turned upside down. They walked on upriver in silence—mother, father, child amid all the shams of their abruptly obsolete, discontinued life.

There was no conversation at supper, either. The mood was tense, and Carl started to consider it all the result of a bad hypnosis and he didn’t want to be drawn in any further. First, they had to eat, then clear the table and wheel everything back into the kitchen on the serving trolley, a small, two-tiered cart with a chrome frame. The muffled rolling sound it made on the carpet, long familiar, the soft clatter of the dishes as always, as if things could only stay this way forever—after all, that’s what everything here had been set up for. The cart was lifted over the doorsill in the hallway, this was his father’s job, but today Carl leaped up to help him, carefully, so that nothing slipped off. “Now there’s someone who sees what work needs to be done,” was his father’s highest compliment.

Like two children, they pushed the trolley together down the hallway and into the kitchen. Carl felt helpless but he lent a hand and was suddenly overcome with a feeling of homesickness, with a longing for homecoming, for rest, sleep, the return of the prodigal son, something along those lines. Longing for that exhaustion that descends like a seizure, which only ever struck him here, at home, on his childhood sofa: “Oh Carl, why don’t you stretch out for a bit? And here, take the pillow. Do you need a blanket? Here, take the blanket …” First the pillow, then the blanket, which meant: defense against all self-doubt, the obliteration of all distress.

When Carl and his father returned from the kitchen, his mother was on the sofa. She seemed nervous and fitfully crossed her legs. These days she wore her hair short and smooth like a young boy’s, which made her look even smaller than she was. Still, it was easy to see how much strength there was in her, how much determination. His father held him by the arm.

For a moment, it looked like they were only play-acting: sudden departure, parting, escape—and the papers on the flat surface of the secretary, lined up parallel to the edge. They reflected the light from the small fluorescent tube covered by a shade and Carl had to close his eyes for a moment—land certificates, deeds of transfer, a gift deed form certifying that all this would now belong to him. Carl Bischoff, the only child of Inge and Walter Bischoff, born 1963 in Gera, Thuringia, “currently a student”; “student” was only written faintly and in pencil.

“It would be nice if you could look after the place, that’s to say, we’re asking you to.” Or: “Could you look after the place, that’s to say, we’d like to ask you to.”

Later, Carl couldn’t remember the exact wording, just “ask” and “look after” and that he had allowed the handover, which in the moment had a solemn aspect to it, to happen without resistance, at least without any mention of his own plans. The brute force of incomprehension left him at a loss for words and eclipsed everything else.

That little word “why?” presented itself but was not admitted, on the contrary, “why?” and any answer, Carl sensed, would only lead deeper into that state of unreality that, it turned out, became absolute when he learned that his parents planned to attempt their departure (that’s how they referred to it) separately after Giessen. From the central transit camp on, they would initially each try on their own, in order to “double our chances.” That’s how his mother had put it and that was the name: “Central Transit Camp.” She was trying to keep her voice steady, but Carl could hear that separately after Giessen had not been her idea.

“We’ve thought it over carefully.”

And then: “Your mother always wanted to leave.”

Carl didn’t have the slightest doubt that Inge and Walter (since adolescence he was in the habit of calling his parents by their first names) belonged in this house, in this life and no other, which is why he started in on the dangers and risks, of which he only had vague notions. His mother looked at him.

“And you, Carl? Where have you been all this time—without a single word? Do you have any idea how worried …”

Then the handover.

A tour of all the rooms, the new oven’s features, the electrical wiring and the fuses, their farewell to it all. An envelope lay on the secretary. “Five hundred marks,” his father said.

“Any other questions?”

It was already late evening when they returned once more to the garage, down in the valley, next to the railway embankment. For a while, they stood next to each other, their hands in the cone of light cast by the workbench lamp while Walter explained how the tools were organized. That summer, a few important and rare pieces had been added to his collection, including an ignition timing mechanism and a distance gauge with twenty tabs (0.05 to 1 millimeter), priceless tools. There were larger, cruder tools on the metal shelves, but the valuable ones were hung on the wall over the workbench with rubber straps made from preserving-jar rings or mounted on brackets Walter had made himself from narrow slats rubbed with recycled oil: tools of various sizes, ordered in increasing and decreasing sizes that, together, created a kind of landscape (a homeland), gleaming and cool.

Carl’s father wasn’t wearing his overalls, which he usually put on when he was in the garage, just an apron, the gray, knee-length apron that was reserved for work on the house. He picked up one of the new socket wrenches and simulated its use. The raised voice, the pauses, the “so” and the “then,” the tone of his detailed explanations and the message that hadn’t changed since Carl’s childhood: the world demanded concentration—and patience; the world was rickety, fragile, in a questionable state, but it could be repaired.

“Do you know how long it takes to set up a collection like this?”

“Quite a few years,” Carl replied.

“A lifetime,” his father said.

As a sign that he understood, Carl fingered the tabs on the new distance gauge. The thin steel was slightly flexible and rather greasy. The grease smelled sweetish, edible … Here in the garage’s dim light, with a tool in his hand, Carl could have begun speaking, confiding in his father, suddenly it seemed possible, this was the opening made only for that. He could have recounted what had happened to him in the past year (befallen him was the old, more precise word). The breakup with H. and why he’d stopped going to class and why he had hidden himself away from the world.

He wouldn’t have told his father everything, of course. His attempt with the pills. The Kröllwitz Clinic. The empty days.

He pictured it: his father’s worried expression, but no reproach; a nod, a pause—

“Finally, one more thing about the car.”

Carl put down the tool. His father asked him to get behind the wheel of the Zhiguli. He turned on the ignition and pointed to a small light below the tachometer that lit up or not depending on the motor oil, but Carl had already stopped listening to what his father was explaining.

They sat next to each other in silence for a while, in the semi-darkness of the narrow precast concrete garage, and Carl was unable to imagine his father’s life. Walter’s hand lay on the black imitation leather dashboard, right in front of Carl’s eyes. As if he wanted to show Carl his hand one last time in farewell, how his hand looked exactly like his son’s and not only in its shape, the lines on their palms were identical; the same history was written in their hands.

“You don’t drive up to the gates of a refugee camp in your own car, I expect,” his father said, then fell silent. The tool landscape shimmered in the rearview mirror. Carl realized that the distance that usually stood between them was suspended.

“No, I … I know,” Carl stammered. That was all.

His father seemed to still be pondering, but then he got out of the car and Carl rested his arms on the steering wheel.

As a child, he would sit for hours behind the wheel of the Zhiguli, making rumbling sounds; clutch, shift, gas. A light went on in the apartment building across the way. Effi lived there—Effi Kalász, with whom Carl had been in love since eighth grade without ever telling her.

A Story

Carl slept in his childhood room, on the so-called teen bed, an orange and green striped sofa bed. Back then, just before his fourteenth birthday, his parents had redecorated his room. He’d been surprised by the unannounced disappearance of his fold-down bed, which could be turned into a cabinet during the day very easily, and that his mother never missed an opportunity to call “very practical and, most importantly, space-saving.” In fact, the new furniture left only a narrow path from the door to the window, under which stood Carl’s desk. The disappearance of the fold-down bed and the appearance of the teen bed signaled (still) the end of his childhood.

Carl looked around. The only books in his parents’ house (aside from his father’s reference books on computers and programming languages) were now kept on the shelf above the teen bed: the Meyers encyclopedia in nine volumes with the one-volume supplement, a Duden dictionary, a dictionary of foreign words and two small encyclopedias (one of nature and one of history). Everything else was unchanged. Also unchanged was the play of light and shadows on the room’s ceiling, the street noise and the voices from the entrance lobby. Someone had spray-painted “The revolution will prevail” in red on the base of the apartment block across the street.

Before he fell asleep, Carl heard footsteps overhead, heavy steps, not the steps of a girl: Kerstin Schenkendorff, the daughter of the man who kept the Hausbuch, a log of all the building’s tenants and their guests. He lived in the apartment above them, she was a few significant years older than Carl; what had become of her? He remembered the night of the story. Inge and Walter had gone out, which rarely happened. Carl counted as one of those children parents proudly call “sound sleepers,” but this time there had been a monster, a dragon chasing him unrelentingly and with an enormous appetite. Carl screamed and woke, drenched in sweat. He ran into his parents’ bedroom, but it was empty. He ran through the apartment: no one there. Only the dragon, still hiding somewhere, so Carl had to escape but the apartment door was locked. He’d pounded on the door and called, maybe even screamed, and then, at some point, he heard Kerstin Schenkendorff’s voice outside on the stairs. She spoke to him soothingly, calmed him down, and asked “if a story wouldn’t be nice?” Carl crouched in his pajamas, he pressed his ear to the door, snuggled up to it (dear door) and heard the soft rustling of the house, then, behind the door, the story that Kerstin started telling him, and kept on telling until he fell asleep.

The next morning, Carl drove his parents to the border. Even before the sun rose, his father had brought the car up from the garage and set the keys next to Carl’s plate. Carl saw the keys and he felt a certain pride although he knew that what was happening could only be wrong. Weren’t they his parents? With their quiet, daily life organized down to the smallest detail along with a particular love of order and repetition? A few platitudes from his schooldays drifted by: “the historic situation, the historic moment …” The historic moment has turned your heads, was Carl’s view, but he didn’t say it. He did not feel superior, but rather at a loss.

One possibility was to keep thinking of himself as their child. Parents knew what they were doing and sooner or later the wisdom of their decisions would become clear. It would emerge, just as it always had. And after all, you could look at it in a completely different way: in their own way, Inge and Walter were contributing to the revolution that was taking place everywhere. They stopped showing up at work, they left their positions and prepared their escape, if you wanted to call it that. His parents! They were the unlikeliest refugees Carl could imagine.

The matter of the accordion was upsetting. His father had dragged the old, black case with the instrument up from the basement. He had attached straps that enabled him to carry the bulky monstrosity on his back. He wanted to take it with him, that much was clear, but what for? Carl knew that the instrument belonged to his father, but he’d never seen him play it. Like so much that was stored in the basement, it came from a distant past that was shrouded in darkness.

“Why do you want to schlep that thing along, Walter?” Having to ask this question was unpleasant for Carl. It was as if he were holding a mirror up to a child and running the risk of making him unhappy in a single blow.

“To play now and then,” his father replied. “I think I’ll take it up again.”

It was the usual breakfast: fresh butter, sliced cheese and warmed rolls from the Gera bakery cooperative, where his mother had worked (until the day before) in a four-person department that was responsible for creating new recipes. Four gourmets, as his mother emphasized, including two pastry chefs (the way she pronounced Konditoren sounded like Doktoren), masters of the trade with decades of experience. Her job was to save costly ingredients by calculating an “ersatz.” Apple seeds instead of almonds, for example. Green tomatoes instead of candied lemon peel, and so on. Over the past years, the term “substitute” had been substituted for “ersatz.” When the small group sat together, racking their brains over what could be substituted for what, Inge took notes. Carl’s mother was the secretary, and she wrote everything down, even the most far-fetched suggestions. They often held very long and serious discussions before finally drawing up the “substitution calculation.” On the day of the tasting, they would meet again. Naturally, they didn’t have enormous expectations (as his mother put it), but they did harbor a certain hope (utopian, not easily justified, perhaps the kind fostered by alchemists at the end of their experiments when they’re about to lift the lid). Each of them had, nonetheless, gone to great trouble, thought long and hard, and taken a risk.

“Then you look away and chew,” according to Inge’s rendition. “You chew and can’t bear to look each other in the eye, and no one wants to say anything.”

Carl’s mother found it painful. She had learned her skills from her mother on the farm. Even as a girl she had enjoyed baking and did it often—twenty kinds of cake for each celebration, which were then set out on cake boards as big as cartwheels in the vaulted cellar, on what they called the cake rack. Carl remembered it well—the peculiar Huckelkuchen (“bumpy cake,” which was also called “camel cake”), the legendary cheesecake (a legend they all rehashed every single time) and the search for the shelf with the chocolate streusel cake, which was the most important for the child Carl.

In his father’s opinion, it was a matter of crossing the border as fast as possible. Walter talked about Willy Brandt’s speech in front of the Schöneberg town hall. It was in all the papers. Something in the speech had revealed to him that the border would only stay open for a short time. He explained it to Carl with the laws of fluid mechanics, “all you need is a little bit of physics, a simple trick, to relieve pressure.” And the Russians are still here, too, after all. That was his strongest argument.

He had chosen Herleshausen for the border crossing. That’s where buses would be leaving from and there was also a train station nearby. Rain had started to fall during the night and was now streaming down. Carl’s mother said, “The sky is weeping.” She saw it as a sign—of what exactly remained her secret.

They spoke little during the drive, the discipline of flight and concentration on what was most essential prevailed. Carl was the driver of the getaway car and in the car were two refugees who had to be smuggled westward. Strange: it was his father who was sitting in the passenger seat. And the woman in the back seat was his mother, who was checking the documents one more time, all stowed away in a plastic bag and secured with a rubber band.

“You’re driving too far to the right. You’re driving in the middle of the road again, Carl. Not so fast, please …” Nothing, not a single remark. Carl waited for one, after the Hermsdorfer interchange, he even wished his father would make a remark.

The gentle pull of the Thuringian hills on the left and right of the highway. The view of the road, with the spidery tar-patched cracks in the concrete. The Zhiguli ran over large black spiders along with the gaps between the slabs, the rhythmic beat of the tires—a jungle noise and a strange thought: maybe what he had done in his life so far wasn’t so wrong and pointless after all. It was just my own way of driving, Carl thought, to put it very broadly and simply.

Part of their preliminaries, as Carl’s mother described it, involved getting new and better glasses from Wunderlich Opticians on the Sorge (the main boulevard in Gera), for the fine print in the masses of forms she believed they’d be required to fill out over there. “Bärbel, I’m taking a cure and need a pair of glasses,” was Inge’s explanation to her optician, who had filled her request almost overnight. Inge had also bought two sturdy backpacks, the ones called hunter’s rucksacks, “because, and this is important, you always need a hand free on the go, you understand Carl?” She was agitated and kept repeating the sentence: “You always need a hand free.” She had drawn up lists and imagined various situations. One of these was that “in the camp” she would wear pajamas at night instead of a nightgown as she usually did; the toilets were surely out in the hallway, at the end of some corridor, maybe even in a courtyard you’d have to cross at night, perhaps under the eyes of a camp guard or other refugees drawn outside by the dozen simply out of excitement. And yes: there would be queues for everything, to get food, to get passes, for every stamp and every certificate. “But now we have to see it through, one way or another, you understand, Carl?”

Her self-confident demeanor, her way with words. Carl knew that nothing held his mother back once she had set her sights on something. The neighbors all liked her, even Schenkendorff. Oh, all the friends, colleagues and neighbors who now, after decades of tried and tested fellowship, had to be left behind without a word, no goodbyes, no farewells, no notes with homemade biscuits wrapped in a napkin that his mother had always gladly left on doorsteps and work desks as “a little token,” as she put it.

Giving everything up, leaving.

Although what was happening was weighty and life-changing, Carl later had only vague memories of their conversations; maybe he was in shock. He accepted their decision, he respected it, what else could he do? And finally: who could know what would prove right or wrong in the end?

On the evening before they had chatted about this and that, but not about anything that would have made things clear to Carl. There were a few useful phrases at the ready—“imprisoned an entire lifetime” and so on, which was generally accurate, but his parents did not use them, that wasn’t the reason. Carl understood that there had to be more to it, something that could blow it all up (and did blow it up), even though they had long ago worked out a plan for the rest of their lives. It was surely stored away safely somewhere with their documents, on the bottom of the box in the secretary or some other such spot.

It became ever clearer to Carl that he basically knew very little about his parents and only carried around a few faded, childish images from the album of his schooldays and adolescence. Had he ever really thought about them? Was it children’s obligation to think about their parents when they became adults? And if so, when should they start? Were the mid-twenties already too late?

He stared ahead at the roadway. The Thuringian hills to the left and right. My parents are leaving the family home—a very odd and sad sentence at this moment. Before, leaving was reserved for the children. Children went out into the world, not parents. And then the parents worried about their children, and so on.

The border crossing was crowded: passersby, the curious, lines of cars and streams of pedestrians—the country seemed to be dispersing in a giant migration. Among the crowd there were more than a few with rucksacks and suitcases, strong, young travelers who seemed to have met here by agreement and be supporting each other. There was no one his parents’ age. With the large, black accordion case on his back, Carl’s father looked like a displaced person trying to save one of his household effects. Fittingly, the ruins of an unfinished highway overpass rose from the valley. “They can keep building now,” his father murmured. It was an odd remark, since he assumed the border would be closed again soon. In the background, at the foot of the watchtower, soldiers stood holding their machine guns nonchalantly in front of their chests and Carl secretly agreed with his father: the whole apparatus could be put back into operation at any time.

Once more, Carl offered to drive all the way to Giessen, to the central refugee transit camp. His father looked at him as if through a tunnel. Spontaneous alterations were out of the question—on this point, at least, the course was familiar. His parents’ lives would change, forever, that much was certain, but the upheaval was following the old rules. And it wasn’t clear that they would ever see each other again.

Then the goodbye. A temporary parking lot, actually it was just part of a field, muddy pastureland, dark, gloomy soil. His parents wore their green plastic rain ponchos from their mountain holiday in the High Tatras, which covered their rucksacks and made them look like cosmonauts preparing to set foot on a strange new planet despite adverse conditions. “What wonderful trips we’ve taken!” This exclamation followed every holiday. His mother also wore her Tatra hiking boots made of brown buckskin (the thick soles, the jagged tread), and only then did Carl notice that under her gray sweater vest, she was also wearing the checked hiking shirt she had bought in Tatranská Lomnica, not far from the Slovakian mountain hut they rented for many years, settling in with a trunk full of soup packets, canned cheese, and homemade liverwurst. His parents had always been very frugal. Now they were leaving everything behind and taking on the West. Like one of their hiking tours.

Finally, they hugged Carl: stiffly and somewhat reserved, their cool, damp rain ponchos like a final rejection, entirely unintended, and maybe that’s why he had to fight back tears. When he started the car, the waving began. His parents waved and when he drove away, they were still waving, and in the rearview mirror, Carl could see them, still waving, and he waved, too, his arm stretched out of the window, letting his sleeve get drenched in the rain. Waving until the one leaving has disappeared and then a bit longer for good measure—that was the family tradition. Later, in a dream, Carl saw them all standing there, waving, his parents in their place and he in his, at great distances from each other, and each in their own lives: I’m here, that was me, goodbye my dears.

“Our parents should have a better life.” Something was wrong with this sentence.

The Child Carl

The short hallway, the wardrobe’s dull sheen, and in the dim light his mother’s summer coat, watching him mutely. For a while, Carl padded from room to room and sank into the absence: walk, don’t think. He breathed in his parents’ smell. He tried to be as quiet as possible.

In front of the television, the two chairs upholstered in black and red bouclé. To the right of the television, the cabinet with the record player, the anti-static cloth folded neatly next to the unit. The replacement cloth, unused, in a plastic bag behind it. Strangely, all these things were still there, stoically continuing their existence.

The bedroom was basically taboo, the parental zone. Carl sat on the bed (on his father’s side) and pulled out the drawer of his nightstand. He was a child again, home after school, looking for the Polish playing cards with the four aces (four women), who were topless as soon as the card was tilted slightly.

“What business of yours was it to look in the drawer, Carl, explain yourself.”

He stood up and tried to smooth the bedcover. Even moving a chair required overcoming resistance. He didn’t just drag it across the floor, he lifted it, carefully.

On the evening news they showed a map with the new border crossings. The trains of the German National Railway were said to be “at two hundred percent capacity” and photographs of the train stations were shown. For a second, Carl thought he saw himself in a crowd of people. In two rapid steps, he reached the window. The neighbor’s lights: they were still on. He closed the curtains and turned off the ceiling light. At midnight, a recap of the past days. He remembered the warning his father claimed he’d heard and had to admit that Willy Brandt had chosen his words very carefully, almost as if the speaker were secretly leaving open something pivotal. As if the whole thing could still turn out to have been a great bluff. At the end was a report of unrest in several units of the National People’s Army and the camera pensively panned along the walls of the border dog kennels at Potsdam-Wilhelmshorst. They were surrounded by tall pine trees on which lay the warm light of the setting sun. A primeval forest, for which Carl felt a brief longing.

He had to hold his position and “secure the hinterland,” that was the agreement in short. He would stand by in case help was needed; in any event, he would wait for word from over there, as his father called it. “You’re the rearguard, Carl, as it were.”

The rearguard. The word annoyed Carl, but he had ultimately agreed. What else could he do? He didn’t understand exactly what was happening to his parents, but the sincerity and gravity of their request was clear. It was the least that he, their only child, could do for them in these unfathomable days—the very least.

Carl found his mother’s old typewriter in one of the linen cupboards and he set it up on the writing desk. It was a Consul. He liked its heavy, semicircular casing. It was cool to the touch and gleamed in the light of the small neon lamp. Typing took effort, each letter a hammer blow—the sound of steps overhead, someone said something, muffled voices. He tried at half-strength and the writing faded.

It was a kind of a poem about a soldier who passed through the Straits of Gibraltar alone in his U-boat. There were five lines in it that Carl liked a lot—as if written by a stranger. He recited the lines again out loud, and the image of a completely different life flashed before his eyes: he had five lines that granted him permission. He stood and paced around the room; a warm feeling of happiness.

Next to the typewriter lay a few books he had brought with him: Anna Akhmatova, René Char, Gertrud Kolmar. He wrote down excerpts in his notebook. Copying was a way to get closer to the sacred. It was the American method. A kind of religious service. Afterwards, he read his own poem again. There he was, underwater, on the bottom of the sea, with his “Nautilus.” He was utterly alone. Solitary and silent, he passed the Moroccan roots of Africa. It was still good.

Two days later: “There will be no return to the prior state of affairs.” Carl wondered if his parents were following the news and if they might possibly (consequently) correct their plans and decide to turn around and return to Gera. He wished they would, then the doorbell rang.

He was in the hallway on the way to the kitchen. Alarmed, Carl stared into the semi-darkness over the door. The bell was old, electromechanical, a tiny clapper that beat rapidly against a bowl-shaped piece of metal, a kind of bell. After the clapper stopped, there was a lingering sound, the bell rang—and rang. It was this sound that hung in the air, swelled and gained an audible outline. An outline of the furniture and coats in the hallway and now even of Carl himself, he could feel it on the cold edges of his ears, he’d become audible.

“Carl, open up! I know you’re there.”

Schenkendorff’s asthmatic voice, like an avalanche of small, dusty gravel. Carl’s ears seemed frozen, seemed to have grown in the hallway and all of a sudden weren’t small anymore, but expansive and full of hidden corners. I know you’re there: suddenly he was the child Carl again, hiding because he had “neglected his homework,” the child who had caused trouble in school, “undisciplined” and “at risk of being held back,” as Mrs. Klotz, his homeroom teacher, had described him. One evening, she had shown up at suppertime …

“Carl! Is everything alright?”

Part of the “strategy” was that Carl (if possible) would not talk to anyone, at least not for the first few days. “We need the head start,” his father had said—or something to that effect. His job at the Gera data processing center (he programmed the large computers) was the reason for the secrecy. He was a person entrusted with secret information, that was the official designation. Carl did not believe that his father harbored concrete fears because of this. He just wanted some breathing room, to gain distance, Walter had said. All in all, it would simply be easier if their disappearance remained undiscovered in the building for as long as possible, easier for them and for Carl.

“I’ll be back, Carl!” Schenkendorff called.

The next morning, he slipped two sheets of paper under the door, like in a movie. It was a form for registering arrivals and departures in Gera-Langenberg and the district of Gera with the police. Carl wondered if Schenkendorff had known everything all along.

Later, that evening, Carl pushed the chairs and the table against the wall and laid out two long rows of pages on the orange-brown carpet. He left a path between them so he could walk up and down and inspect the writing.

He now saw that the poem about the soldier in the U-boat could be improved here and there. But the rhythm was good, and he had caught the underwater feeling. The right mix of longing and desolation, at least it seemed so to him. Not out of personal experience or because he was living through something similar (in a broad sense)—this thought would not have occurred to Carl. On the contrary: the man in the U-boat was poetry and if it was poetry, then it had nothing to do with his own (trivial) life. It was the other world, the one that was worth the trouble (none other was). Carl dreamed of the day when he would manage to write a great, authentic poem. Something as great as T. S. Eliot’s Four Quartets, for example.

The carpet was too soft a surface to write on. Here and there the tip of his pencil pierced the paper—tiny holes.

“Breathing holes,” whispered the child Carl who had been crouching next to him the entire time. “Breathing holes for your poems.”

“Do you think that’s good?”

“Yes.”

“And what do you think of the poems?”

The first days in Gera: no news, no letter.

Conscientious parents, always reliable.

Separately after Giessen.

He tried to picture it. Some camp, a sports hall maybe, or a defunct railway station, somewhere in the north. Camp beds and cotton blankets, near the sea, high and low tides. What would they live on? They didn’t have any relatives in the West, no acquaintances, none of the care packages that imported jeans, coffee and the bewitching odor of the West that so many people talked about. And no Western money either, of course, never. Only the provisions in the hunter’s rucksack. His father’s heart medicine, did they think of that? Many who left had some kind of address. Maybe they weren’t particularly welcome, but they had an initial goal, a name, a street—instead of a train station or a reception camp. He pictured his parents, side by side, diving into a thickening fog of confusion.

Once a day, Carl crept down three flights of stairs to the mailbox and often a flight further down to the cellar where the preserves and cider were stored, hundreds of jars and bottles on metal shelves, provisions for the rest of his life.

When darkness fell, he would go out on the balcony to smoke. From the balcony, there was a view far into the Elster Valley. To the left was his old school. He just had to lean over the railing slightly to see it: two stories, long, brightly lit corridors between the rooms, the physics lab, the chemistry lab, Bunsen burners. Class started at ten minutes to seven. First the short warning bell, then the long final ring. At six thirty, breakfast—his parents had already left for work. Two rolls, already spread with jam, coffee substitute and milk from the blue thermos (the blue thermos from his childhood, he suddenly saw it, alarmingly distinct, with the small dent, the chipped enamel, the slightly loose, unevenly stained seal on the screw top) and next to his plate, his mother’s daily note:

“Dear Carl, Good luck with your physics assignment. Concentrate hard and avoid careless mistakes! Please light a fire when you get home, and don’t forget the ashes …”

No letter, no news, day after day. When Carl was tired and distracted, he occasionally thought: they’ll never leave. But they had left. Parents, to whom nothing really serious could happen. Separately after Giessen.

The refrigerator and the freezer were well stocked, the provisions from their old life, enough for weeks, months maybe. His mother had divided everything into servings, in milk cartons she had cut open neatly and washed thoroughly. From the faded blue script, Carl recognized that the cartons had been reused several times. He deciphered the words “Milking Parlor,” words he liked. The combination of milk and parlor—now that was clear and powerful poetry. Each carton was sealed with a small rubber band. A small strip of cardboard with the contents and date was inserted under the elastic. He contemplated the frenetic handwriting slanting into the word’s progression. Refugee script, Carl whispered into the freezer compartment and with a jolt the refrigerator sprang to life. In the appliance’s drone he could hear his father’s admonition to keep the door open as briefly as possible, not longer than two or three seconds: “You should know what you want beforehand. Concentrate.”

After three weeks in Gera, he had to admit that he was no longer fit for anything. He could only manage to read for a few minutes, then he had to get up, to move. Because he didn’t want to meet anyone or speak to anyone (especially not about his parents having disappeared without a trace), he only left the apartment at night, like an animal leaving its den under the cover of darkness. Sometimes he roamed the Gebind, that was the name of their neighborhood, seven Altneubauten apartment blocks, four stories tall as always, plus a few other buildings, rising in tiers on the hillside toward the forest. And sometimes he walked along the river, following their old walk to the Franzosen Bridge. He saw the shimmering black water of the Elster and up ahead the silhouettes of his parents, the leading man and lady of family traditions. He saw how his mother put her arm around his father’s waist, laughed and pulled him close. Even as a child, he had not only felt boredom on their Sunday walks along the river, but also a certain sadness, about which he knew nothing specific. Maybe it was that he only ever followed the unit his parents formed from a certain distance, he slunk after them (so to speak) and so was left alone with the river, in which his fantasies drifted, whirled around, and, in the rapids, went under like an overloaded raft … When the stream of his thoughts grew too frenzied, he stood, rooted to the ground, and had to breathe, breathe, until it all calmed down again. Meanwhile, his parents drew ever farther away with the confident, perfectly matched steps of a thousand walks together.

He drank too much and talked to himself. He went to seed and did not write a single, serviceable line. Instead, he watched television all day and all night. The headlines and reports were always new, always more incredible: a call for a general strike and former government officials put under house arrest, some already in prison. The old order was falling apart with breathtaking speed. Accompanied by hard cider and preserved plums. The border dog kennels with the golden pines were still worth a report. In the kitchen, dirty dishes piled up, rubbish littered the floor, the smell of rot. At night, Carl tiptoed down to the cellar in his socks and noiselessly returned upstairs with fresh plunder. The cider was extremely sweet and gave him a heavy, piercing headache; maybe he drank too quickly.

Now and then, Carl lingered a bit downstairs. He felt listless and needed a rest before climbing the stairs. It was as if his parents’ sudden departure had sucked all the available strength from him. Separately after Giessen. The missing persons reports increased: people from the East who had disappeared into the West without a trace, gone underground. People from the East who left their mothers, fathers, husbands and wives (and, yes, their children, too), crossed the border westward and vanished. This was the opportunity to change their lives. First the Iron Curtain, now a golden bridge. How easy it must be to do away with a few of these adventurers and freedom seekers, to bury them if some advantage could be drawn from it …

Should he drive to Giessen? Request an inquiry with the refugee registry? Or just start by filing a missing persons report? A hundred thousand people were underway, allegedly. A hundred thousand since the border was opened.

“You don’t drive up to the gate of a refugee camp in your own car,”—that’s just not proper, is how Carl had understood his father. It was in keeping with his respect for the process of escape in uncertain conditions. But above all, as Carl saw it, it accorded with his trusting nature—his confidence that a certain (good, proper) conduct would elicit a certain (good, proper) reaction. And maybe he was right. Maybe this kind of humility and penance was necessary for a refugee from the East. As extraordinary as the step they had taken was, and as chaotic and audacious as it all seemed, they wanted to do it respectably. They wanted to be good refugees, which made Carl’s heart constrict. His poor parents. They would never make it. They weren’t callous enough, their elbows not sharp enough. They weren’t familiar with the worst things, they were too old, too fragile, too vulnerable, and they were schlepping a large, black case around with them.

Only now, down in the cellar, standing in front of the shelves of cider, did fear reach Carl. That is, it had been there for a while, the whole time, in fact. It squatted in the Anchor-brand canning jars, in the canned blood sausage, the pears and plums, it crouched in the dark corners and smelled of rat. It gnawed at the piles of old newspapers, chewing the paper into tiny shreds and spitting them out. It devoured the cyanide lures and didn’t die, on the contrary, it grew.

Carl had lit a candle (the light hadn’t worked for years) and leaned his back against the coal shelter. His gaze fell on his grandmother’s armoire, which at some point had been brought down to the cellar and stowed between the potato clamp and the storage shelves. One corner of the armoire was charred. As a child, he had tried to set it on fire, dreamily and with great patience: Carl-the-stupid-child liked to stare into small fires, absently, without a single thought. On the wall facing him hung the large panel of his model train set, shrouded in ancient sheets. Through a gap you could see a landscape, a train station, little plastic people with their feet glued to the surface. All these things were composed of fear. Somewhere out there, history was raging, and his parents were roaming around in the middle of the turbulence.

Maghrib al-Aqsa

Sayings were in the air: “One after another.” Or: “A fool takes on too much at once.” And again and again, in his mother’s warning tone: “You can’t have everything. You can’t have everything.”

Carl let the apartment deteriorate, maybe that’s why it started to exert pressure on him. It demanded of him, simply put, that he maintain the old life, as a stand-in. Afternoon coffee at the table in the front room at 4:30, bath day, garage day, and so on, the only possible sequence in this place. “We’re abandoned, too, understand?” The television armchair by the window had spoken (his father’s chair) and it wouldn’t calm down, so Carl began talking to it: “Why it happened this way, I mean, what they really have in mind—we don’t know. It’s a kind of secret, you see, their life-secret.”

Schenkendorff had slipped new forms under the door. On these, Carl’s name was already filled in, the address, too, very neatly, in capital letters with a ballpoint pen. A fourteen-day registration deadline.

What was the point? It would have been easier to take the forms, exchange a few trivial words, and make something up. Carl realized that he was ashamed. He was ashamed that his parents had left “under the cover of darkness,” as the neighbors would put it. After a few decades in the community, they’d simply disappeared without a word.

Because he refused to live according to the apartment’s customs, there were mishaps. In the kitchen at night, in the dim light: he held the spoon upside down and the chalky liquid of a medication he’d wanted to take dripped from the dome of the spoon onto his shirt. Nothing serious, but the little accidents accumulated, creating a hostile atmosphere. A glass shattered and right away Carl stepped on a shard with his bare foot. He was seized with anger. Out there, borders were falling and he was stuck in Gera-Langenberg. Abandoned by God and the world, and above all by Walter and Inge. It was the first time that he felt the seed of offense.

He went into the kitchen, pulled aside the curtain and peered down the street. In the entire building (three staircases, four stories), only one family had a telephone line—the Schulers, who received the emergency calls. “Only for true emergencies, please,” was the stipulation. If Mrs. Schuler appeared at your door, you knew that something had happened, and over the years it became impossible to see this neighbor from the next staircase without picturing some misfortune coming (or remembering a past misfortune). When Mrs. Schuler left her apartment, she usually had her dog with her, a wearied terrier mix whose head always sagged and who never barked. His entire life long, Carl would picture misfortune every time he saw one of those shaggy dogs—mute and with drooping ears. But snuffling and shameless, too.

The street was empty, and no phone call was good, very good actually. He had to learn to control his feelings; he shouldn’t be so sensitive. Next to the sink stood an open bottle of cider. Carl finished it off, quickly, as if there were something he finally had to finish, then went to bed. It was late afternoon. He pulled the Meyers encyclopedia off the shelf and read. Morocco: Maghrib al-Aqsa (Arabic, “the western place”). Officially al-mamlaka al-ma¯gribiyya, kingdom in northwestern Africa. History, geography, Middle and High Atlas Mountains and “beyond the Atlas range, past a fringe of oases, the transition to the Sahara.” There was a small map indicating natural resources, climate zones and the largest cities. Carl read the names out loud. Agadir, Tangier, Marrakesh, Fez, and then he repeated again and again: Fez, Fez. “Everyone has only one song,” Paul Bowles, who lived in Tangiers, once said. Café Hafa, Pension L’Amour, tin roofs, cats, the Maghribi sun—his dreamed-of life, it was happening there. “That’s where it will be,” Carl whispered and fell asleep.

He dreamed of Corporal Bade, who counted seconds in the voice of a talking horse. A good thirty seconds and the guard had mustered in full uniform—field packs, steel helmets and weapons. Carl reported for duty and the horse began to whinny: “Eeeeefffffiiiii—the only woman Soldier Bischoff eeehhver loved, or whaa-aat? Riiiiight, soldier? A good fuuuuck? Did you fuuuck Eeeff-fi?”

When Carl woke, bathed in sweat, it was midnight. Why did he dream of the army? As so often, in situations in which he felt confused and disoriented, stories from his past resurfaced: on the one hand, the perpetual longing for solace and redemption; on the other, bad decisions, missed opportunities, magical moments wasted—all those promising occasions before they had passed.

In his socks, Carl padded down to the cellar and returned with two fresh bottles. He was on the third floor (the Koberski family to the left, the Dix family to the right), when the door above sprang open—Schenkendorff! This time, he was waiting for Carl. Carl began to sprint, three steps at a time, but he slipped just before his goal. He threw the bottles into the air; it was a reflex. He tumbled into the apartment, kicked the door shut with his heels and hit his head on the wooden coatrack—all in a single movement.

For a moment, there was complete silence. Carl’s ears became ice-cold.

From somewhere above his head, the doorbell’s ringing rippled out over him. It carefully outlined his motionless body on the hallway floor. Effi knelt down on the other side of the door and asked “if a story wouldn’t be nice.”

“Yes, a story, please,” Carl whispered.

“You do understand that things can’t go on like this, Carl.”

“No, Effi, not like this.”

“Now listen.”

Zhiguli

First Carl drove to the post office on Zeitzer Strasse and explained to Mrs. Bethmann that all mail sent to his parents’ address should be held at the branch to be collected: poste restante was the word. He filled out the relevant application, a short form.

“Poste restante,” Mrs. Bethmann repeated, revealing a strip of her large white incisors.

“And for how long, Carl?” She was a beautiful woman about his mother’s age, maybe a bit younger, her jet-black hair in a ponytail. When he was a child, she reminded Carl of Mireille Mathieu, who at the time was called the “sparrow of Avignon.”

“Two months, maybe? Until the end of January? And I’ll call regularly, here at the post office, I mean, to find out if anything has been received. Would that be possible, Mrs. Bethmann?”