Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Sprache: Englisch

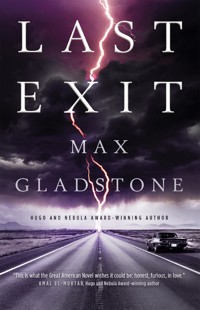

From the co-author of the bestselling This Is How You Lose the Time War. Gaiman's American Gods meets King's The Dark Tower in this electric, captivating road trip across America and alternate realities to stop the apocalypse, from a Hugo and Nebula Award-winning author. Imagine that the American highway system is a vast magical network binding city to city. By soaking up magic from intentionally directionless travel, initiates can slip into alternate realities. Stray too far from our America, though, and things get weird. And dangerous. And terrifying. When visionary mathematician Zelda Qiang was in college, she learned how to travel from one alternate reality to another. Her response was to take her friends on a road trip to strange new worlds. Six of them set out. Only five returned. Zelda's lover, Sal, betrayed them: she walked into the jags―sharp cutting shadows like cracks in space―and didn't come back. Now Zelda still walks the road alone, a wandering magus keeping the jags from breaking through. But now Sal is coming back―with Dark Things in tow.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 1001

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Leave us a Review

Copyright

Dedication

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-One

Chapter Twenty-Two

Chapter Twenty-Three

Chapter Twenty-Four

Chapter Twenty-Five

Chapter Twenty-Six

Chapter Twenty-Seven

Chapter Twenty-Eight

Chapter Twenty-Nine

Chapter Thirty

Chapter Thirty-One

Chapter Thirty-Two

Chapter Thirty-Three

Chapter Thirty-Four

Chapter Thirty-Five

Chapter Thirty-Six

Acknowledgments

About the Author

LEAVE US A REVIEW

We hope you enjoy this book – if you did we would really appreciate it if you can write a short review. Your ratings really make a difference for the authors, helping the books you love reach more people.

You can rate this book, or leave a short review here:

Amazon.co.uk,

Goodreads,

Waterstones,

or your preferred retailer.

Last Exit

Print edition ISBN: 9781803360300

E-book edition ISBN: 9781803360317

Published by Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd.

144 Southwark Street, London SE1 0UP.

www.titanbooks.com

First Titan edition: May 2022

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

© Max Gladstone 2022. All rights reserved.

Max Gladstone asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

This is a work of fiction. All of the characters, organizations, and events portrayed in this novel are either products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead (except for satirical purposes), is entirely coincidental.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

To S and C, as we walk

Alma mater floreatQuae nos educavit

CHAPTER ONE

When the worst of the bleeding stopped, Zelda hitchhiked back to the Bronx to say that she was sorry.

New York wasn’t safe for her even then. She crept in sideways, kept her head down, and did not think about possibilities, about spin or rot or all the other ways the skyline might have looked. Those thoughts were dangerous here. But she had to tell Sal’s mother she was gone.

Years ago, when Zelda and Sal and the others left to begin their time on the road, she had dreamed that one day she might come back to this city triumphant, to stride down her long boulevards as confetti rained from rooftops and bands played marches. They were young and proud, and they knew that if they tried, they could fix what was broken in the world. It was a stretching early summer then, the glass-walled streets casting the blue of the sky back up so they’d felt as if they were marching off to storm the gates of heaven. They were saviors. They were adventurers. They believed.

Zelda made her way back alone. The 138th Street subway station was a grungy straight tunnel tagged with graffiti in hard-to-reach places, a tired, worn station best used for homecoming, just as it had been when Sal first brought Zelda here to meet her mother, all smiles at her gawping, cornpone girlfriend. Zelda had never left South Carolina before she came north for college. She was used to backcountry roads and towns with two stoplights. More people crouched on New York’s few square miles than lived in her whole half of the state, all those lives weaving around and through one another.

She climbed the dirty stairs to a street that had not changed much since she had been what she’d then thought was young. Her mistakes climbed with her. Down on the platform, a girl cried, “Hey, wait!” Zelda almost did. She almost turned, and a nightmare voice suggested that if she had, she would have seen Sal.

She climbed instead, into the wet-dog heat of an August afternoon.

When she knocked on Ma Tempest’s door, she heard the old woman wailing upstairs. So, she knew. A premonition, a dream, or just word traveling fast. Ramón might have called her, or Sarah, or even Ish. Zelda knocked, and kept knocking, and no one came. She bruised her knuckles, broke the scabs on her fists, and left bloody prints on the olive-painted door. Her heart was a hairy, howling thing too large for the cage of her ribs. She had lost Sal. She had lost Ma’s girl, her favorite and firstborn.

She had gone off onto the road with her lover and their friends and ruined everything. She wanted to kneel at Ma Tempest’s feet, bow her head to those thick sandals, and let herself be beaten until blood flowed from her back and the white bones lay bare. The bloodletting might relieve the pressure in her chest and quiet the voice inside, repeating: It’s your fault.

It was her fault they’d left in the first place, and so was everything that came after, and the fact that Sal was gone. After all that, to need punishment or absolution from Sal’s mother, now, was a crime greater than any she’d committed in those road-bound years. Except, perhaps, for stepping out on the road in the first place.

But she had nowhere else to go.

So she stood there, a tired woman in her midtwenties, sobbing bloody-knuckled, slumped against a door on a sidewalk in the Bronx. The most natural fucking thing in the world. Dog walkers took no notice. Trucks rolled by on the Cross Bronx Expressway. A cop car blared its siren at her once and she jumped, turned, glared. They drove off snickering. A bodega cat sauntered out and sat across the street to watch.

She kept knocking. This had brought her across ten states, straining to outrun the shadows on her heels. After Montana, there had been nothing left for her in the world except for this olive door. If she could look Ma Tempest in the eye and say that she was sorry, that it was all her fault, if she could take the blow across her cheek, then she could go and find a cozy little hole to die in. Or she could leave—walk out into the Hudson and never, ever come back. There were pills she could take, needles she could slide into veins, and if all else failed, there was good old legal booze. She could rot her liver and die jaundiced, miserable, screaming. That would be worth it. That would be right.

One conversation, and then she could go away forever.

So she knocked, and sobbed, and felt the steel in her spine bend.

The door took her weight.

It opened. She stumbled, caught herself.

A girl waited inside. Skin Sal’s own deep brown, hair in puff balls. Cheekbones that with another ten years’ growth could mirror Sal’s, and big, dark eyes blinking behind glasses mended with masking tape, lenses thick enough for Zelda to see herself in the reflection. Not a sister but close to it—a cousin Ma had the raising of. June. Zelda had met her when she first came to visit during college. She was barely walking then.

June stood straight, silent, with the uncanny stillness of a child watching an adult (which Zelda had never, before this moment, felt herself to be) lose her shit.

Zelda trembled to see her, this girl who might have been her Sal long before it all went wrong.

Just say it, she told herself, just say, She’s gone, or I’m sorry, or anything with an ounce of blood in it.

But before Zelda found her voice, June said: “She doesn’t want to see you.” Precise and clipped. Zelda reached for her—just to touch her arm or the black hand-me-down Wu-Tang T-shirt—and the door closed in her face and left her out there on the sidewalk alone, with tears stinging her eyes and snot running down her nose and blood on her knuckles where the scabs had opened, and the sky uncaring and perfect blue, solid as a dome overhead.

She forced herself away from the closed olive door, away from Ma Tempest, as untouchable as the past.

Since she had not apologized, she could not now disappear to die.

So she took her first step away.

* * *

Every year she came back.

Every year she’d failed a little more. Every year she’d gained a scar or two. Road dirt worked into her skin. Every year the country grew a little darker.

She’d been told, back in college, that she and her friends were going to save the world. She’d been told they would seize its reins and turn it toward truth and light. No one said it in quite those words, no one would be so gauche, but the intent was there. You, they said, are special. You will help the planet, you will guide the nation.

They’d been out in the world a decade now or nearly, those bright young things—the fuckups like Zelda and the ones who got it right, the polished and prepared debate-team children, the masters of the college political union. They’d been out there in the world for ten years, and somehow there was less truth each year than the last, and the light was dying.

Even in the years of hope, she’d seen it. In the great cities of the coasts, there was a sidelong wariness, glancing out of the corner of the eye at something not quite there, a high-pitched laugh of desperation, almost a scream.

And in the heart—on the long open roads—the tension grew. Small-town cops dressed in black now and sported rifles like the ones they might have used before they got kicked out of the army, in one of the smaller stupid fucking wars. She got their sidelong glances—head to foot and back up, lingering along the way—a woman traveling alone, ratty and ragged. Their fingers twitched when they looked at her. The small-town diners and truck stops got hard, and they’d been no easy places before, America always quicker to call itself friendly than to make friends. The smiles, when she found them, seemed shallow and fragile. She felt hated there, in the dark that seeped through the fault lines in those lips.

Heat lightning flashed, silent in the gathering air.

The world moved on. Or had it always been this bad, and she just never noticed before? Facebookless, lacking mobile phone, and with no internet but the public library, she was left to feel out the moment on her own. Those false smiles soured and became the baring of teeth. Cop cars on grim city streets slowed when they passed her—the eyes behind the windows covered in dark glasses, reflective like the nighttime eyes of monsters.

Every year she came back and knocked on Ma Tempest’s door until her knuckles bled. The door never opened. The Bronx changed with the years: coffee shops opened and the young rich, or at least the young not-quite-poor, filtered in. But the important details did not change at all: the blood, the olive door, her memory of June’s dark eyes.

* * *

The tenth year after she’d lost Sal, Zelda was living in the back seat of a hard-used Subaru in a small town in Middle Tennessee, waiting for the end of the world.

It might happen any day. She worked as a checkout clerk at the local Walmart and slept in the parking lot with the other losers and retired mobile home people, and every day she felt the rot gather, the wet foul heat of it, the summer heavy as a guillotine in this time of change. She had followed the rot here across three states, guided by the hackles on the back of her neck, by yarrow stalks and the faces of upturned tarot cards. This was the place. There was a mystery here, and she would solve it, or she would die—which would solve one mystery at least.

A boy—eighteen, nineteen, in a black T-shirt, with a homemade tattoo of Thor’s hammer on his wrist, always staring at his phone—wandered up and down the fishing aisle. She’d pass him sometimes as she restocked. While she was around, he never, ever looked at the guns one aisle over.

Sometimes he’d glance at her, though. Never quite brave enough to match her eyes.

It might be him.

Or: Mona, her sometimes partner in the checkout line, her eyes deep-set and red, her shoulders down, her face bruised sometimes, or her wrist. She offered Zelda weed, and they smoked out on someone’s back forty under the stars, and Zelda coughed because it had been a while since she last smoked and when she remembered just how long and whom she’d been with, she began to weep and passed it off as more coughing. Mona wasn’t from around here either, she said, by which she meant she was from East Tennessee, Smoky Mountain country, not used to flatlands or the local flavor of dirty strip mall. When she worked her lighter, the spark caught reflections of something jagged in the depths of her eyes.

Mona’s husband drank and stayed up late into the night, typing on the internet and watching videos about how she was the root of his problems. He’d been a good man, she said, when they met, and he still was, just confused. Zelda said she didn’t care what was in people’s hearts. You only had to watch their hands.

Mona said that she had a secret place, a clearing in the woods out back of their small house, where she’d go when it got too much. She’d pretend that no one could find her there, and she’d lean against the rough bark of one tree and talk into a cleft, tell the dark space her fears, and sometimes, she said, she thought it whispered back.

It might be her.

You had to be lost to let the darkness in. You had to lie awake turning and churning around a coal in your stomach, body aching and mind alert to the whispers behind the door. You had to need something you couldn’t imagine, need it more than life or sanity, you had to pray not to some airy aftermath god of smoke and cloud and resurrection but to a grotesque wriggling belly-deep god of Now. No one comfortable could muster that razor need. But you never knew who was hungry. Or sick. Or curled around a fishhook of what he thought, or the TV said, the world denied him, or gave to someone less deserving. Everyone else was less deserving.

So where would the end begin? Where would the rot break through, and who would call it?

She never knew. She envied movie detectives the clarity of their cases. In real life, you never know what your problem is, unless someone loves you enough to tell you. Philip Marlowe just had to drink and wait and not even hope—sooner or later, a beautiful blonde with legs long and bright and curved as the swell of swift water over rocks would stride through his door, of all the doors in the world, with a mission. Zelda would never be half so lucky, with the mission or the blonde. And she was running out of time.

Every morning she crossed off another day on the calendar hanging in the Subaru, one day closer to Sal’s birthday, one day closer to her date with that olive door. One week left, and the drive would eat most of that if she wanted to do it safely.

She could give up. She didn’t have to sneak a third of the way across America and through the black hole orbit of Manhattan to stand on Sal’s mother’s doorstep and knock and fail for another year. This was her life now, had been for the better part of a decade: wandering alone, haunting back lots, shoring up the sandcastles of the country as they crumbled. Give up what was gone. Take the L.

She considered it, drunk, for the better part of an hour. Then she went hunting.

It was harder to do things this way than to wait for the rot to manifest. First she had to build spin. She circled the small town in her Subaru, to the extent there was a town to circle. There was a town square, at least, a city hall in red brick and a movie theater built in 1950, where she’d spent some of her spare cash to watch a forgettable action picture starring a guy named Chris. The other buildings on the square were shuttered and empty, except for the attorney’s office, and there the curtains were drawn. Vacant storefronts sported peeling decals: COLE’S HARDWARE, a liquor store, a pharmacy with a punning name, all gone now.

The buildings in the town square had been built to last three hundred years. They would stand while the stick-and-board houses she drove past rotted to dust. But they would stand three centuries empty. Why build anything to last when the whole country lived on borrowed time?

She drove circles around the city hall, drinking the strangeness of the shuttered place. The sun glanced off windows as haunted as Mona’s eyes. Turn and turn and watch it, feel it—suck the spin of the wheel and the suchness of the passing world down into the pit in your heart, where it gathers like cotton candy around a carny’s wand. She listened to the wheels of the Subaru on the seams of the road. And when the spin churned inside her, she popped the glove compartment without taking her eyes off the road, withdrew a handful of yarrow stalks, and tossed them onto the empty passenger’s seat.

The yarrow stalks told her that she’d almost missed the turn.

She heeled the car hard right, felt it tip, and slid through a narrow gap in the wide-open gulf of the two-lane road, onto the right track. Hunting.

She had worked out how to do all of this way back in college, had perfected it on the road with the others, and with Sal. Driving by yarrow stalks and by the transformations in her head, Zelda remembered other cars and other worlds, lifetimes ago: Ramón’s black Challenger with the red racing stripe, Sal in the passenger seat, the two of them blissed out and talking math as they slipped from streetlight to streetlight and all the darkness of the world rolled over Sal Tempest’s skin. They had dared each other out into the deep, like girls at summer camp, not realizing just how far either of them would go to please the other, until the lake’s depths yawned bottomless beneath and they’d both lost the strength to swim for shore.

Just a little further.

* * *

That’s what Sal had said every time Zelda balked—those full lips parted slightly as they curled into a smile. Just a little further, her hand on Zelda’s wrist, cheek, thigh, drawing her after.

Zelda had never known anyone like her when they met. It had been orientation week of Zelda’s freshman year, at, of all the absurdities in retrospect, a Christian Fellowship mixer, one of those ploys the campus evangelicals used to rope in faithful who might otherwise hear the siren song of the convulsive drunken rest of the campus. Zelda went because she’d promised her mom she would—Zelda, who’d come to campus book-smart and quiet and careful, a little South Carolina Lancelot, armored with purity and hair clip and sensible skirt against the corruptions of the northern school to which her parents couldn’t bear not to send her.

To the collar of her unremarkable blouse she’d clipped the enamel rainbow flag pin she took from the alphabet soup alliance table at the activities fair that afternoon when she’d thought no one else was looking. She went to the mixer because she’d promised Mom, and she wore the pin because she’d promised herself.

Surely, she thought, heart in her throat as she walked down York Street to the events space where the Fellowship met, one gothic pile down from the campus newspaper, surely it would be different here, surely the Fellowship would get it, at least the other kids would—she still thought of herself as a kid then. Surely this was a small concession, set beside her willingness to come here at all, to keep her feet on this particular path when she’d left North Bend and family and church behind.

And yet.

One thing to tell herself this, and a whole different thing to grip the wrought iron handle of the great, heavy wooden door and pull with her legs and back until it begrudged her entry. To stride into the brightly lit room with the yellow walls and the punch bowl on the table in the rear right corner and all the kids in polo shirts. That heavy-bellied man with the bouncing step would be the pastor, turning toward her like an artillery battery. She already felt as if she’d walked in naked with a fanfare. How could she have been so dumb? She knew the rules. You never showed anyone else your soul, not even a piece of it, or you would give them something to pray against. Of course it wouldn’t be different here. The rules didn’t change in adulthood, no matter what anyone said. You kept your surface clean and tidy, made yourself look like everybody thought everybody else was supposed to look. You mowed your lawn so no one thought to look in your toolshed. And now here she was, exposed to the withering heat of the pastor’s kind smile. She might have run, but there were other kids between her and the door already, the congregation extending amoebic pseudopods to draw her in, digest her.

Anyway, she’d promised Mom.

The pastor knew his job. He welcomed her, offered her punch, a name tag—made a joke about the princess being in another castle that confused her too much for her even to pretend to laugh. Pastor Steve was his name, but of course he wanted everyone to call him Steve.

“And where are you from, Zelda?” Pastor Steve asked.

Where, indeed. The world was small, smaller still with a name like hers, and in that moment as she met his eyes, the part of her brain that calculated fast but figured people slow churned away. There were only so many churches in North Bend, South Carolina. One might without trouble call them all, if one were a youth pastor wondering whether the new girl with the rainbow pin might have worn one at home or whether her family knew, or cared. She had meant to contain this small experiment, this small moment of rebellion—to test herself, to masquerade as the kind of person who would wear the pin not just on trips to bars in town but to church. And now the mask might glue itself to her face. She imagined the phone call soon to follow, and Mom on the other end of the line.

Her mouth went dry and her tongue was too large to fit her mouth. The room with the punch bowl seemed too bright and inhuman and close. Cheery faces pressed in to crush her as the floors and ceiling opened out to infinity and down forever. She felt herself begin to fall.

“Zelda!” A voice from out of sight, and then a girl dawned through the crowd—tall, sharp, and dark, her hair in tight braids back from her face. Her arms flung wide and she embraced Zelda, firm and warm, and Zelda’s own indrawn breath caught her speechless. The girl smelled of sandalwood.

“Sal,” Pastor Steve said without a trace of chill.

“Zelda’s a friend from back home,” Sal said, turning around to face the pastor, arm still around Zelda’s shoulders. “Grew up down the block. Ma asked her to meet me here—that’s okay, right? All who are hungry, let them come and eat.” She had a brownie from the snack table in her free hand. She took a bite. “Though I guess that’s the other guys.”

“Will we see you at youth group?”

“Expect me when you do.” She saluted with her brownie hand, two fingers to the temple like a Girl Scout. “We’ll get gone, Pastor. I’m sure you have fishes to multiply.”

And, arm still around Zelda’s shoulders, Sal drew her from the room into the dark, down York Street with the tall castle walls of the residential colleges to their right. Loping beside her, Sal chewed, swallowed. Zelda watched the muscles of her jaw and neck. Sal tore off the part of the brownie she’d bitten into, offered Zelda the rest, and asked questions. “First week’s rough, but you’ll get used to it. Where are you from, really? What’s your roommate like? Don’t worry, at first it seems like half the kids here are from Westchester, but they’re just, you know, different. And there’s plenty of the rest of us around. We just don’t talk about high school as much. You learn the patterns, anyway. I’m still getting used to the guys who wear their shirt collars popped.”

The voice that had frozen in Zelda’s throat when she faced Pastor Steve babbled now like a spring brook, answering, and Zelda felt herself melt to Sal’s side, though she had to stretch her legs to keep pace.

Cars rolled along Elm past the Au Bon Pain where the woman stood selling roses, and somewhere some orientation group raised a cheer loud enough to make Zelda flinch. Sal pulled away, looked at her. Zelda felt her departure as if a magnet pulled them together.

“Thank you,” Zelda said.

“You can’t leave everything behind,” Sal said, as if she hadn’t. “I made the same mistake when I showed up. Spent half the year wrestling with people who wanted to save my soul.”

“Did they call your church?”

“They tried. Turns out my pastor’s cooler than I thought.”

“Why did you come back?”

“Brownies.” She finished her half. “And to rescue young ingenues.” Gesturing with her chin to Zelda, grinning.

She’d learned that word her second day at college. Her roommate was into musical theater. “I’m hardly.”

“Oh.” Sal appraised Zelda: her sensible blouse, her skirt past the knee, her long hair gathered back. “I must have been mistaken. You’re clearly piratical. Scourge of the seven seas. I came back,” she said, “to spike the punch bowl.”

When Zelda laughed, she realized it was the first time she’d really laughed since she came to town, a laugh untainted by confusion. “You didn’t.”

She took a flask from her inner jacket pocket, unscrewed it, upended the last drop into her mouth. “Either it was me or the miracle at Cana.”

“So—what now?”

“I thought I might show you around. But with you being so piratical and all, you obviously don’t need my help.” She grinned, mocking, inviting. The light did interesting things to her silhouette. She must have noticed Zelda’s sway toward her as she drew back; she turned away slow enough to torture.

“Wait.”

Sal stopped at her word, one eyebrow raised.

“What if I’m a pirate,” Zelda said, “in disguise?”

“A ruthless killer, faking innocence. A murderer in a french braid.” She flicked Zelda’s hair.

“I’m here on a mission. I feel naked without my cutlass. I spent hours staring into a mirror, practicing how to flutter my eyelashes.” She demonstrated, and got the hoped-for laugh. Sal took her arm again.

“Come on, Captain Kidd. Let me show you around.”

All night Zelda followed Sal from courtyard to courtyard, skimming the edge of parties—peering through astronomy club telescopes on Old Campus at the moon when it peeked through orange sherbet clouds—a pitch-perfect mock ingenue. Playing that role, she had the freedom to ask the questions she’d not felt comfortable asking before—where people came from and what it meant, what Westchester was and what Stuyvesant might be, where power lived on campus, how that power worked. Zelda had never been around class before, not this flavor of class, anyway, which the kids (she wasn’t thinking of them as men and women yet) pretended didn’t exist, even though it was obvious that some people, like Zelda, were working in the library, and some people, like her roommate, would spend Thanksgiving break in Switzerland. Sal knew it all, and liked sharing what she knew, with cutting asides that made Zelda laugh. Zelda wondered, while they walked, at the depth of Sal’s insight, and wondered also if this girl was lonely: watching, judging a world with little place for her. After a year of study, in self-defense, it must feel good to share what she’d found with someone else.

After hours of wandering, Sal led her up the stairs of the A & A Building, floor by floor to the rooftop deck and then to the fence that separated the lower deck from the true roof. Just a little further. Sal’s eyes sparkled with reflected streetlights and the few stars that pierced the orange shell of New Haven sky.

Zelda lay beside Sal on the pebbly roof and pointed up into the swirls of yellow, purple, pink. “A comet!”

The warm length of Sal twisted against her as she raised her arm to point at another patch of weird and mottled sky. “Spaceship. Aliens.”

“Looks like a plane to me.” She nestled into the hollow of Sal’s arm. Where Sal pointed, Zelda could almost see the ship—curves of crystal and translucent metal, impossible to build, a gross affront to aerodynamics, useless to imagine anything like that leaving a planet’s surface, a perfect rose in the sky trailed by—

“Rainbows,” Sal said. “That’s how you know they’re aliens. Like in E.T.”

“I think that’s a dragon over there.”

“Dragons don’t come north of Pennsylvania,” Sal said. “Everybody knows that.”

“Not me.” Zelda didn’t have an accent, but she could put one on for effect. “I’m just a plain, simple country girl, on mah own here in the big city.”

“This isn’t a city.”

“I can’t see but three stars. That makes a city.”

“You forgot the comet. And the spaceship.”

“And the dragon.”

“I said, no dragons this far north. They don’t like the winters.”

“What about Viking dragons?”

“European varietal. Hardier. Your American dragon is temperate.”

The colors turned in the sky above, and on the street below, the Christian Fellowship stumbled from their orientation mixer, warbling hymns, drunk on the Holy Spirit and the contents of Sal’s flask. Zelda found herself on her side. Sal’s chest rose beneath her tank top, and fell. Her hoodie’s wings spread out beside her on the roof. She wore a gloss that gave her lips the shine of still water, a pool where a big cat might kneel to drink.

If you’d asked Zelda hours ago, she would have said that of course she’d kissed people before. But now, searching back and comparing each of those moments to this one, she found only memories of being kissed, moments where kissing had happened to her. And this, what she thought this might be—there was nothing passive in it, nothing of the pawing pro forma junior prom date with Billy Klobbard or the deeply uncomfortable truth-or-dare with John Domino. She wanted to do fierce things to this woman, and that need, owned fully for once in this strange place, scared her.

Sal was watching. “It’s okay to ask, you know. If you want something.”

“May I?” Zelda’s lips pursed around the m.

“Have you ever done this before?”

She would not lie. “Not . . . as such. Not exactly. No.” The shame was real. She felt it color her cheeks.

“I should not take advantage of an innocent.” A dare, an invitation. Sal’s hand on her side, on her hip.

She had a vision then of the two of them perfectly alone in the center of a vast and hostile universe, these few square feet of pebbly rooftop the heart, the city and that sickly melted-candy sky just a shell, and beyond that shell an immense and profound darkness, a writhing night full of blades and fangs and needles pointing in, the cosmos a trap and her the mouse creeping, whiskers atwitch, toward the trigger. And she prayed to a god she was no longer certain she believed would listen: Let me have this.

“I’m not an innocent, remember? I’m a pirate. In disguise.”

Sal’s face eclipsed the trap of the world. She was smiling. “Come on, then, Captain Kidd.” Her breath warm. “Just a little further.”

* * *

Zelda drove Tennessee back roads, following the yarrow-stalk map.

There was more witchiness to her current lifestyle than Zelda liked to admit. She’d worked it all out on paper from first principles back at school, theorems building on other theorems. First you gathered spin, accumulated history and memory, possibility, strangeness, dredged the depths of your soul for everything you did not know was true. Then you held it inside, let it charge you and change you. You gathered uncertainty until what might be bloomed into what is. There was mathematics under the magic, and stranger parts of physics, but every time she practiced her art like this, she felt the math give way to a deeper dream logic of chance, memory, and regret.

It never should have come to this: her, alone, on the road. She should be driving with Sal right now. Instead of this beat old Subaru, she should be driving the Challenger Ramón had built in his uncle’s garage, she should be trading barbs and theories with Ish, bobbing her head while Sarah made up lyrics to sing over radio jazz. They should be young and unafraid. Somewhere back up the road, they still were, and even though in all of Zelda’s travels she’d never been able to turn back time, when she was on the hunt like this, charged with spin and open to every possibility, she sometimes thought, knew, that if she only turned the next corner, she’d find them all there beside the parked Challenger, Ish cooking while Sarah picked out a song on the guitar, and she could warn them all. Or, if causal laws forbade her from changing the past, she could at least pause at the foot of the gravel path to watch them, an older woman they might barely recognize, weeping before she went away.

She would never hurt her friends again. That’s what she told herself, every time. If she had a second chance, a third, a ninth, she’d do it right.

The Subaru slipped into a long gravel driveway. Her hand found the parking brake on its own. At the top of the hill squatted a small yellow house. The sun was setting and the porch lights flickered on. A screen’s uncanny blue flickered through the living room windows. This was the place.

She knew this driveway, this hill, those squinting angry windows. When she picked Mona up for a late-night rendezvous, she stopped at the foot of the driveway so Alan would not hear the engine.

So, the rot was here after all.

She wanted to leave. Sometimes the detective knows the answer to the case, but turns away. Lets the crook go. Works on anything else. But the yarrow stalks had drawn her. And that olive door was waiting.

Wind blew an earthy scent from the trees—green and growth and rot and behind those, a silver ozone smell of sour moonlight.

She stepped easy, left the gravel for wet grass. She took no weapons with her, save the spin coiled around her heart. If she lost control, there was nothing a knife or gun could do to save her.

The rot felt her approach. It curled back and drew the forest around itself like a quilt. Hiding, yes, but also daring her. I have made this place my own. Come after me. Step out into the dark.

There were ways to hunt carefully, to approach sidelong and slantwise, so even spiders would not feel you drawing near. But those ways took weeks, and she had to leave tomorrow. Which meant ending this tonight.

She entered the forest.

She walked slowly, on the balls of her feet, testing the ground as if it might break. There was a chance she’d not be noticed crossing the lawn, so she spent a little of her spin to make that chance the truth. Soft breeze ruffled tall grass around a rusted lawn mower propped up to show its blades.

The sun vanished. The sky grew deep and orange. Sal used to sing “Mood Indigo” at sunset when they camped. But she had lost Sal and now she was alone.

The forest, seen from the driveway, had been simple Tennessee scrub, dense with brambles and young trees. Now, as she stood at its mouth, on its lower lip, she stared into a gullet lined with teeth. The rot on the breeze had deepened. She smelled carrion, spilled meat, and opened guts.

When Zelda was eight, she had lost her dog. They had five or six depending on how you counted—but Goof was hers, the one who ran to her when she came home from school. The Tuesday he didn’t come, she thought little of it, but when two more days passed and no one had seen him, she packed herself a bag and set off up the mountain, looking. Maybe he was hurt, or stuck. Maybe he’d taken something down up there and was dragging it home inch by inch. She thought, in the simple way she had that made her so good at math, the trick of thinking not in gulps but step by step, that to find him, all she had to do was climb the mountain behind their house and come down in a spiral, covering each foot of ground. She took salami from the fridge, and a flashlight.

The sun set while she was on the mountain. Her parents and her brother climbed up to look for her, but they did not have her careful mind and she hid when she heard them coming. If they took her down the mountain, she’d lose her place and have to start her search all over. She crouched in the hollow of a rotting log, breathing low, and when a grub fell from the pulped wood onto her cheek and bounced off, leaving a wet smear behind, she did not squeak.

Her family gave up the search. She did not.

When the moon set, she heard something else looking for her. Quiet steps in the dark, a rustle of leaves, a caustic ammonia stink. Kids at school said there were mountain lions in the hills, but kids at school said a lot of things. Whatever it was, the silence came closer. Her hands slipped on the heavy flashlight. She imagined how teeth would feel in her arm.

What would it feel like to be swallowed? Could some part of you be aware?

The smell and silence neared.

She found the flashlight switch, swept its beam through the dark, and saw—movement, a nothingness departing, perhaps a wake of wind.

There, between a tree and a rock, she saw a swollen mound that she knew was Goof.

His belly was puffed up with decay and his tan fur was torn where scavengers had found him, and there was blood. Grubs churned in his wounds. Her clearest memory was of that flop of ear inverted, trailing in the mulched leaves. He hates when I do that; he shakes his head and yowls until the ear sets right again. And in Zelda’s mind as she looked, hates became hated.

Her life was different now. So was his. Every moment they’d shared, rolling together in the grass, her hands trailing over his head in her lap as she worked out sums or puzzled over the whirling shapes of helicopter seeds, was infiltrated, overturned, by this ending in the trees. It led here—this weight of skin and bones, this smear on the rocks, this churning stench. All of it inevitable. He’d run out here, smelling a challenge, and in the dark he found it, and made an end.

She could not change that. She felt baptized by the putrid flesh, by the needle tooth marks on bare bone where his meat had been gnawed away. They crept in, even into her moments of joy, and changed her life so it was not what she had thought.

But kneeling there with her dead friend’s head staining the knees of her overalls, she felt something tear-hot and firm as a blade inside her. It did not form. It had been there always, and only now did she reach for it. This would not be her story. The carrion eaters did not own what they devoured.

She took off her jacket. Her hands squelched into his fur when she lifted him, and muck and shit came out. In her backpack of supplies, she’d brought a spool of parachute cord because of what Sam Gamgee in The Lord of the Rings said about rope. We’ll want it if we haven’t got it. With the rope and two sticks and a knife and her jacket, she made a sling, and used her backpack straps for a harness, and together they started down.

At first down was all she had to go on, since the moon was set and the stars confused. The small sounds of the forest bowed when she passed by, out of respect, perhaps, or fear. When first light threatened in the east she knew what direction east was, and shifted course. Goof’s stink filled those hours of descent. In school later she’d read Karamazov, read about the monks trying to hold vigil over their great Elder Zosima and deny that the man’s corpse smelled, because he was so holy, and she’d know what they were about.

What she was doing was right. That rightness should have made it okay. But still she gasped him, rotting, into her.

Her parents found her at dawn in the backyard beside the chicken coop and a mound of fresh-turned earth, two sticks at its head tied with paracord as best she could into a slanting cross. Dry-eyed, though there were tracks of tears down her cheeks. Her hands black with gore and a spade between her knees.

They hugged her—gingerly, she noticed, around the stains. Made the sounds she expected, love, dear, don’t you dare, rarely congealing into sentences. She’d buried her jacket with him. She said she’d lost it. Father commented on the cost of getting a new one. She stayed in the shower for what felt like days, scrubbed herself red and raw with every soap she could reach, even Mom’s special one that looked like a seashell and was never used. Scrubbed beneath her fingernails, and the pads of her hands and feet.

When she stepped out of the shower that first time and stood wrapped chin to shin in one of the good fluffy towels that smelled of chemicals that smelled like lavender, and stared into her own large and open black eyes in the mirror, home and safe, she drew a breath and smelled the faintest hint, the slightest airborne suggestion, of the body cavity of her dead dog.

The next thing she remembered, she was bent over the toilet, retching because there was nothing left in her to come up.

In more than twenty years, she had not forgotten that smell, and it was that same stench exactly that blew from the wood behind Mona’s house, through the darkness and past the trees like broken teeth.

She drew a staggered breath and stepped, hunter soft, into the shadows.

Her sneakers sank into the mulch, came out wet and stained. Cold wet wind bearing that same old rot whipped her jacket around her, raised dust devils of powdered leaves, then, on her next step, stilled. She walked through the cloying stink. She breathed it.

A branch snapped behind her.

Even though she knew better, she looked over her shoulder.

The trees went on forever. There was no driveway, no small yellow house. This was no scrubland forest. What if the old primal wood, the wall of green that European explorers found after their illnesses scoured the continent, had not vanished, had not been burned or cut clean but curled into a tight ball and hid, a vastness of forest lurking hungry as a tiger in shadows, waiting for a moment’s inattention in its prey to spring? That old forest, Zelda knew, would hate her.

In the black halls of the trees, something moved. A suggestion in the shadows, and large.

The rot was hiding, playing off her fears. Move on.

Soft feet padded near. Branches rustled in the still night. Her breath crept up from her belly to her chest, until she panted, in and out, in and out, through her open mouth. Goof had climbed his mountain alone and found something sickle-clawed and silent in the depth of night. He thought he was ready. So did she. Now at the end, they were both alone.

The silence gained a new depth. That rasp might have been two branches struck together—or fur bristling against bark. Was that the click of a claw?

No path lay beneath her feet. The sour moonlight smell was gone. She walked alone beneath mad stars, pursued by something she dared not turn to see. If she did turn and look, she’d make it certain, make it real, that beast in the trees. But if she did not look, she could walk, and spend the spin she’d gathered in her chest into the soil, to will this forest otherwise.

The branches grew so close above that she lost the sky. In that unsure, step-by-step dark, she saw the mountain lion in her mind, as vividly with her eyes open as she would have if they’d been closed: no healthy beast but a rot-mad one, smearing foul black blood on the branches it passed, claws finger-long and curved, its shoulders bunched with muscle and its maw spittle-flecked. A bright pink tongue tested air between the spire teeth.

It reached for her now. It had been waiting in this memory forest for her all these years, knowing one day she’d return without the protection of Goof’s sacrifice. Two paws, each the size of her face, stretched down, down, from the dense branches, hooked claws turned inward, and they would catch her cheeks like fishhooks and drag her up by her jaw into the trees and teeth.

Something brushed a lock of loose hair by her left eye and she almost looked. But with a cry and a final burst of will—this was not happening, the lion was not there, she was not about to die—she spent her spin in warding, and staggered through.

She stood, blinking, in a sunset grove.

Her shirt was soaked with sweat. Her knees shook and her heart throbbed in her ears. Her hands found her thighs. She gasped like a deep-sea diver surfaced on scant air, tears hot in her eyes, too scared to let them fall.

Details of the clearing filtered in slowly: purple sky, few stars, sun declining, and far off to the north, the contrails of a passenger jet. To her left, through a football field’s worth of scrub trees, slouched that mean yellow house. The smell: burnt meat from a neighbor’s bad time with a backyard grill. Beneath that: ozone and sour silver. Spoiled moonlight. She had come through. The rot was here.

It wasn’t much of a grove, all things considered. Just a roundish gap in the trees. You’d have to have a powerful need to use it as a gateway, as a door.

Mona’s need was powerful. Zelda felt the rot here: the hurricane weight of the ending world. There stood the cleft tree, the darkness inside razor-edged, untouched by sun. The rot was small, but Mona fed it secrets, and it grew.

Zelda padded toward the tree.

Within the crack in its bark she glimpsed something breathing, small and fierce as a cornered rat. It shrank back into its hole, its final refuge now that she’d breached all its other walls. She reached into the crack.

“Zelda. Don’t.”

Mona stood at the clearing’s edge, flour on her hands, hair frizzed out. The door to the yellow house was open behind her. She reached for Zelda, trembling.

“You can’t,” she said. “Please. Zelda, it listens to me.” Such hunger around that word, listens. She’d known Mona for less than two months. Long enough to tell how rare that was in her life. How long had she been drowning here?

“It’s young now,” Zelda said. “The first crack in the wall. Your need calls it. But it will grow, and listening won’t be enough for it anymore. It will eat you up and then you’ll be gone, as if you never were.”

“Is this what you do?” Her cheeks were wet. “You go around and take away the last thing people need?”

“It will eat you, Mona. It will carve you open and wear you out and eat other people too. It can’t live in our world. Not like you want. It can’t help you. But I can save you.”

“Zelda, no—Zelda, please—goddamn it, Zelda, stop!” Shrieking, she ran for her, clawed at her arms, her face, too late.

Zelda reached into the crack in the tree.

Needle teeth pierced her palm, and whiplike barbed-wire limbs circled her fingers. The rot-thing bucked and writhed. She hissed from the pain, felt her grip go slick with blood. Her stomach churned. Mona’s nail scraped her eyelid, gouged her cheek. But Mona worked the checkout line, and ten years on the road had left Zelda hard and strong.

Once, she had not been used to being hit. Once, the feeling of something alive burrowing into her hand would have done more than hurt—it would have sickened her, made her scream. But she had been walking in the dark for a long time now.

Once, a friend screaming, begging her to stop, would have made her open her hand and fall to her knees.

She remembered: on her knees on the black-flower road, her hand around Sal’s, as dark limbs pulled them apart and a mad smile played across Sal’s face. It’s beautiful.

Zelda tightened her grip on the rotten thing in the tree. It cut her, but she held it, this alien that Mona’s need had invited in, this monster that would consume her from the inside out. All the spin she’d built observing, wandering this stretch of country, remembering, turning and turning around that town square—all the possibility of the road—she spent it in one fierce breath.

I deny you, she told the rot that was eating her hand. I deny your power. You are not a thing. What reality you’ve clawed for yourself already, from my friend—I take it back.

It wasn’t hard. Like breaking a heart, or a rabbit’s neck.

She closed her hand—a killing grip—felt a squeal, a pop—and then she held nothing at all.

The clearing was still. Stars emerged from a darkening sky.

Mona knelt, weeping. She clutched Zelda’s thigh like a tree in a flood. She always had a spine, an inner rebar that showed only when she was so tired she forgot to hide it. Most days she was all smiles and bright teeth and self-effacing humor, a master of the tricks you used to hide integrity and self-regard when the people you called friends and family would tear you apart for having any. But let a dirty old man in line spit in her face—one had, once—and the steel showed.

Mona had known, whatever happened, that there was this grove, and this crack in this tree, where a growing monster waited, swelling with her need of him.

And then came Zelda. Her friend.

“He listened.”

“I’m sorry.”

“Go away.”

“I just—”

“I don’t care!” She pushed back from Zelda, scrambled to her feet—slapped Zelda across the face. Her hand came away smeared with the blood her nails had drawn. There were deserts in her eyes. “Just go. Now. I can’t look at you anymore.”

She’d heard those words enough to know when they were meant.

Zelda’s hand slid out of the crack in the tree. Liquid shadow dripped from her fingers, smoked beneath her gaze—an impossible substance, a bit of elsewhere. Soon it was gone. Blood remained. Her wounds were painful but shallow. She’d not lose much feeling in the hand. The thin oozing lines and the puncture in her palm would heal, and the scars they left would be thin and pale on her tanned skin, like all the others. People assumed she had a cutting problem, when she let them close. They were not altogether wrong.

Mona’s back was a wall, a cliff. She was safe, she was broken, and Zelda had broken her. She was shaking, and if Zelda were a decent person—the kind of person who would not do what she had just done—she might have tried to touch her one more time, to reach across the gulf and offer some comfort to the woman she’d sat and stared at stars with, give up all pretense of justification and try, for once, to help.

But she had set off on the road ten years before, like she had set off up that mountain chasing Goof. When you began a work like that, you had to take the answers you found: the bodies, the pain, the long-gone friends. You lived with what you found.

She limped away as Mona wept behind her. Steeled herself with memories of why she was here, of what she walked the road to do. There was a wall to the world, a wall made of thorns, and someone had to guard that wall.

She’d dreamed otherwise once. She’d dreamed of changing things. She’d dreamed of the crossroads. But all those dreams went smash.

She flexed her hand. Blood stuck to blood in her palm, tracing the scars across the lines of her life and heart.

The weight began to lift—the summer storm pressure, the suffocation. Air cleared, cleaned with every step she took. She felt lighter and more sure. This, at least, she let herself enjoy. She was guilty of so much, but this was why, the moment when her road sense told her that, for now, the world’s end was paused. For now, the red clock on someone’s wall stopped ticking down. And for a few weeks—maybe even a month—she could find a quiet park somewhere to camp, or a shit job that paid on time in cash, and just survive, without hurting anyone.

With every step down the twisting driveway to her car the sense of doom would ebb. It always did.

But it ebbed slower this time.

Surely, she told herself, this is an illusion. I can still hear Mona crying. This town, this job, got its hooks in me and I’m holding on to the feeling like a cold woman holds on to a blanket as it’s slowly pulled away. By the time I reach the car, it will be gone, and I’ll feel fine.

She reached the car. Fished for her keys.

She did not feel fine.

The weight was not so heavy or immediate as it had been in the clearing. She had won, if you called this winning. But there was something else wrong here, something vast and pervasive, a distant cataclysm that had been obscured behind that small, eager bit of rot in the trees.

Focused on her hunt and the Xs on her calendar, she’d mistaken a sun-shower for the oncoming storm.

Zelda settled behind the Subaru’s wheel. She was so tired, on a level NoDoz and coffee could not touch. Once she’d had the will to change the world, with her friends at her side and her lover at their head. For ten years she’d been drawing from that well. Now, when she threw the bucket in, it struck and scraped the bottom, came up mucky. But still—go on. One step at a time. What else could she do? What else was left?

The sky was a star-dotted shell. Sunset underlit the clouds in blood and fire.

All that endless space, she knew, was the painted backdrop of a stage, billowing, crinkling, tearing as an immense jagged Thing pressed against the cloth. A giant monster prop from another play, it seemed at first, until you realized it was not a prop at all. The world that seemed so still and sure was not.

Zelda gunned the engine, squealed out onto the narrow road, and drove hard north for New York City, ahead of the storm.

* * *

Zelda scuttled into the city like a rat.

Sal told her, on their first visit, that Penn Station had been a palace once, a rival for Grand Central, towering vaults and high windows, cathedral architecture. Then the world moved on. By the time they tore it down, the walls were coated in pigeon shit and the windows tarred with nicotine smoke, and with the rise of the automobile, no one used rail anyway. (Except, of course, for the trains of food that kept the city alive day to day, and for the people who could not afford to drive or park, and and and.) The old Penn Station was a place for gods to saunter in, but when it died it died, and no gaggle of nostalgic protesters could save it. Like the country, the city killed what it thought it didn’t need, fast, and mourned in self-indulgent leisure.

Now Penn Station was a labyrinth. Zelda’s first computer game, on a machine old even when she inherited it from a kid who’d moved away, was a text-only thing where you tried to guide yourself through a maze. If you entered the maze without a map and other tools, the computer would describe every room with the same sentence: “You are in a maze of twisty little passages, all alike.” Zelda used to have nightmares about that maze, about turning and turning deeper underground, the road ahead looking just like the road behind, her torch guttering low. Penn Station was that, only with fluorescent lights and thousands of other people who were all lost too.

Posters on the walls advertised the City’s plans to rebuild the old Penn Station, a new palace; those posters had been there for a while.

She’d hated Penn at first sight, but these days she found it comforting. Here she was lost like everyone else. She could pretend she’d come from anywhere and was bound anywhere else—a poor poet maybe, back from abroad; a graduate student on her way to a conference where she’d meet a lover she saw only at these sorts of things; someone dangerous and desirable with a fencer’s grace and the eyes you got doing hard work under the sun. Someone who hadn’t stepped off the path into the dark.

Someone who wasn’t back in New York for her girlfriend’s birthday to try, again, to apologize.

She climbed the stairs and left the garish twisting paths behind and found herself, for all her fantasies, in Manhattan again, pinned to reality like a butterfly to a board.

Ads everywhere. Fifteen-story musical ads, ads in white for the latest piece of pocket glass to solve all your problems and tell whoever cared to ask exactly where you were at all times, ads for television shows she didn’t watch and clothes she didn’t wear. Full-length ads in bus stop awnings featured a man in a thin black suit cautioning citizens to do their part “to protect the safety of our region,” whatever that meant. Two men in fatigues with automatic rifles flanked the station’s exit. Zelda wasn’t sure how the rifles helped protect the safety of our region, exactly. The men watched the crowd with lidded eyes and the dry contempt of the heavily armed. Zelda recognized that look. She saw it in the mirror.

A briefcase man jostled her. Two women in bright pants cut across her field of vision, talking loudly in Portuguese. Three teenage girls, short buzzed hair, one of them dyed rainbow, another with heavy gauges in her ear, marched past bearing protest signs scattered with glitter. Zelda felt a stab of wonder at the rainbow girl’s laugh, so pure, so unbruised. One of the men with the rifles studied the teenagers as if they might have bombs hidden in their bras. Christ.

There were too many eyes on her, too many cameras, this ground too known. The city in its millions crushed in. This was not her place.