Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Istros Books

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

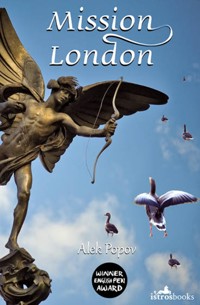

The new Bulgarian ambassador to London is determined to satisfy the whims of his bosses at all costs. Putting himself at the mercy of a shady PR-agency, he is promised direct access to the very highest social circles. Meanwhile, on the lower levels of the embassy, things are not as they should be. With criminal gangs operating in the kitchens, police on the trail of missing ducks from Hyde Park and a sexy Princess Diana impersonator employed as the cleaner, how is an ambassador supposed to do his job? Combining the themes of corruption, confusion and outright incompetence, Popov masterly brings together the multiple plot lines in a sumptuous carnival of frenzy and futile vanity, allowing the illusions and delusions of the post-communist society to be reflected in their glorious absurdity! "A big European novel… his humour is the weapon of a merciless social critic, such as we have seen in the works of Jaroslav Hashec and Ilf and Petrov…" Miljenko Jergović "This is a true European comic novel in the best tradition of P.G. Wodehouse, Roald Dahl and Tom Sharp. An excellent narrative; a great awareness for detail; a fresh sense of humour and most importantly – a sense of moderation. The situations are typically Bulgarian, yet the irony brings a taste of Englishness." 24 Hours This book is also available as a eBook. Buy it from Amazon here.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 352

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

MISSION LONDON

MISSION LONDON

Alek Popov

Translated from the Bulgarian by Daniella and Charles Gill de Mayol de Lupe

First published in 2014 by

Istros Books

London, United Kingdomwww.istrosbooks.com

© Alek Popov, 2001, 2014First edition in Bulgarian: Zvezdan Press, Sofia, 2001

Artwork & Design@Milos Miljkovich, 2013Graphic Designer/Web Developer – [email protected] photo @Anthony GeorgieffTypeset by Octavo Smith Publishing Services

The right of Alek Popov to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988

Edited by Christopher Buxton http://christopherbuxton.com

ISBN: 9781908236-18-0 (print edition)ISBN: 978-1-908236-99-9 (eBook)

Printed in England byCMP (UK), Poole, Dorsetwww.cmp-uk.com

This book has been selected to receive financial assistance from English PEN’s “PEN Translates!” programme, supported by Arts Council England. English PEN exists to promote literature and our understanding of it, to uphold writers’ freedoms around the world, to campaign against the persecution and imprisonment of writers for stating their views, and to promote the friendly co-operation of writers and the free exchange of ideas. www.englishpen.org

“Even if we achieve tremendous successes in our work, there is no reason to be complacent and arrogant. Modesty helps people to advance, while vanity pulls them back. This is a truth we must always have in mind!”

– Mao Ze Dung, Greeting to the delegates of the 8th National Conference of the Chinese Communist Party

1

Kosta Pastricheff was counting the aeroplanes flying over South Kensington. It was a delicate spring morning only slightly overcast. The forsythia in the corner of the garden was covered in bright blooms. Kosta was sitting on the stairs, barefoot, in just jeans and a jumper. An empty bottle of Becks lay at his feet and between his fingers a forgotten cigarette still burned. Planes were flying overhead about every two minutes. The drone of each lingered until it merged with the noise of the next flight. He had counted over twenty. The sound reminded him of the wash of the sea. The windows of the house were wide open and a strong breeze carried with it the fragrance of old fags, swirling the thin curtains around like the veils of a drunken actress. In the dining room on the ground floor, there remained the detritus of the previous night’s party. It was getting on for eleven but Kosta was in no hurry to tidy up. He had the whole afternoon at his disposal.

Meanwhile, another three planes flew over.

A persistent ringing brought him out of his blissful equanimity. At first, Kosta told himself that there was no power that could make him open the door. Then he softened, realizing that such moods are bad for one’s curriculum vitae. He pushed the fag-butt into a gap between the tiles and unwillingly dragged himself to his feet. As he trundled across the foyer, the enormous crystal mirror balefully reflected his figure as if hurrying to expel his scrawny reflection from its gold-plated frame. The ringing began anew – this time shorter and faster.

“Coming, coming…” muttered Kosta and thought to himself, Fuck you!

A tall gloomy gentleman, wearing a greenish raincoat, suitcase in hand, jutted from the doorstep. Behind him, a black-cab was executing complicated manoeuvres to get out of the narrow little street. For a few seconds they inspected each other suspiciously.

“Who you are looking for?” asked Kosta in Bulgarian.

A bitter smile lit up he gentleman’s worn face.

“I am the new Ambassador,” he said, gazing at the bare feet. “And who are you?”

“Umm, me, well…” stuttered Kosta. “I’m the cook”. (The ex-cook – the painful premonition transfixed him.)

“Very well,” nodded the Ambassador. “Might I come in?”

Kosta mechanically moved out of the way; he felt an inexplicable chill as the man passed him. His faint hope that this was a practical joke arranged by the Bulgarian immigrants he had been hanging out with recently, slowly started to evaporate. The man put his suitcase on the floor, looked around and raised his eyebrows in disgust. The cook felt he had better say something first.

“We weren’t expecting you for another two days.” There was just a hint of reproach in his voice.

“It shows.” The Ambassador’s response was cutting and followed a glance into the dining room.

“If we’d known you were coming today…”

“I changed my plans.”

Then blame yourself thought Kosta.

From all those many years spent around the dining-tables of his so-called superiors, the cook had developed a special psychological intuition. Instinctively he knew that his new boss belonged to that extensive and many-branched cretinous family of jobsworths. Yet, there was something else, something behind this man’s idiotic glassy look, which made him unpredictable and dangerous. Suddenly, Kosta realized that this guy intended to settle here. Even more, this was his home now and he – Kosta – was about to become his servant. And that seemed infinitely unjust to him.

At that moment Kosta’s little son crawled up the stairs from the basement, which was occupied by the cook’s family. The child had escaped his mother’s attention and he was jubilant. Mumbling his baby talk, the child stood up and waddled adroitly towards the little table beneath the vast mirror. A frail object on the table had been annoying his primitive instincts for a long time. Kosta had unfortunately lost his former agility, gained through the practice of various sports in his youth. The little one grasped the table’s corner and quickly tilted it, whereupon the little porcelain basket, inventory number 73, crashed to the floor with an apocalyptic tinkle.

“Ding-ding” mumbled the little one happily.

“I’ll give you a ding-ding!” Kosta growled, suppressing his instinctive urge to bash him on the head.

The Ambassador looked on with a poisoned face.

“Child’s play,” muttered the cook unconvincingly. He grabbed the child with one arm and leaned over the balustrade. “Nora!” he shouted. There was no answer. “Norraaaa!” he repeated. “Come here at once!”

“Get stuffed up your shitty ass!” a harsh voice replied.

2

The Mayor of Provadia energetically turned on the hot and cold taps and let the shower pour over him from head to toe. The water slapped his wide Tartar face, smacked his massive, hairy chest and bounced over his titanic belly. The Mayor of Provadia was in a tiptop mood, despite the slight hangover-haze wrapped around his brain. With the completion of his mission his self importance was in full flood. He had visited that mystic, faraway island that had once controlled a third of the world. He had done the museums and the shops. He had seen how the people over there lived. He had drawn the necessary conclusions and could bravely declare that he now had an idea of how the reforms were progressing in that developed western country. He was pleased that he had not lost his mind amidst the splendour and vanity of Oxford Street.

But what made him even happier was the fact that today he was going back to his hometown, Provadia – a town with a glorious history and fertile land.

“Ola-la-la,” he sang full throatedly. “La-la-laaaa.”

The water gushed from all directions like a waterfall, and a feeling of satisfaction and calm suffused the Mayor’s soul. “Lalaa-lala-lalalalaaa!”he continued his little singsong, while thoroughly soaping his short hair.

He did not notice, could not have noticed, the slim tongue of water that had begun to slide under the door and soak the carpet.

Meanwhile, the Ambassador took his suitcase and headed for the first floor without a word. Judging by the greenish hue of his face, Kosta concluded that the magic of love at first sight had failed. The prospects looked ever grimmer.

Halfway up the stairs, the Ambassador stopped and listened.

“There is somebody up there.” The Ambassador pointed up the stairs.

“Ah, the Mayor…” From the tone of the cook’s voice one might presume that this was some sort of pet who had been in the residence for as long as anyone could remember.

The child, twisting in his hands with unexpected strength, started tearing and biting. The cook squeezed him tightly and hissed through his teeth, “You shitty little good for nothing, you’re just like your mother!”

“Mayor?!” asked the Ambassador anxiously.

“The Mayor of Provadia.” The cook elaborated with a hint of condolence.

“And how does he happen to be here this … man from Provadia?” asked the Ambassador queasily.

“They accommodated him. There was no space in the hotel.”

The Ambassador said nothing. He stared at the carpet, which was malignantly soaking up water, as though on board the Titanic. He heard the slap of feet and swearing overhead. The Mayor of Provadia sprang out onto the upper landing, wrapped nonchalantly in a small towel beneath which his Herculean attributes bulged.

“Look at those stupid English!” he started shouting. “They forgot to make one little hole in the bathroom floor! One simple little hole! What’s the big deal? A hole! A drain!”

He rolled up his fingers to make a little hole and looked though it to demonstrate the obviousness of that idiotic omission. Immediately his eyes lit upon the gloomy gentleman, who was inspecting the wet path on the carpet with a pained look on his face.

“Good morning,” said the Mayor and threw a quick glance at Kosta.

“This is the new Ambassador,” said the cook without too much enthusiasm.

“Brilliant!” boomed the Mayor in his loud voice. “Congratulations!”

The gentleman visibly jumped.

“I am very pleased to meet you!” shouted the big man with the Tartar face. “Excuse my appearance. It’s really good we’ve met. It’s a shame I’m going back today, otherwise I could tell you more about these hypocrites. But, I want you to remember one thing: there is no democracy in England! This is not a real democracy!”

Signs of real panic appeared on the Ambassador’s face.

“There is no need for me to explain that to you, of course,” continued the Mayor brusquely. “You’re going to see it for yourself. And don’t forget to remind them about the bathroom. They put in a carpet and forgot the pipe! You must tell them at the first official meeting! And about the W.C.: Did you know that the ancient Bulgarians invented the water closet? I didn’t know myself but, recently, some archaeologists came to report to me. They found it in the dig. A whole 600 years before the Europeans! In the town of Provadia!”

Happy with the effect that his words had visibly had on the important man, the Mayor of Provadia leaned over the banister and shouted to Kosta, “Mate, is there any more of that tasty pig’strotter jelly?”

“There is,” said the cook. “Do you want me to reheat it?”

“Will you have some pig’s-trotter jelly for breakfast with a nice ice-cold beer?” The Mayor turned affably to the Ambassador. “A very healthy way to start the day.”

“Hardly,” the man nodded his head stiffly. The corner of his mouth trembled malevolently. His last words were to Kosta, “I intend to go for a walk. Do not expect me for dinner. And clean out this pigsty!”

He turned sharply and hurried to the doorway, leaving his suitcase on the stairs. Just in front of the doorstep, he stopped, stood rigidly in the entrance and shouted in a squeaky voice, “93!”

“What’s wrong with that lad…?” The Mayor of Provadia shrugged.

3

Varadin Dimitrov left the residence under the influence of a volatile cocktail of contradictory feelings – anger, ecstasy, disdain, and shame. Half in a daze, he crossed the two hundred yards that separated him from the bustle of High Street Kensington and froze in front of the rivers of cars and buses running in both directions. Opposite him, the grass of Kensington Gardens was a tender green. People were roller-blading quietly along the paths like creatures from some distant utopia. Varadin Dimitrov headed to the nearest traffic lights. Leaning on the railings, an elderly English lady was waiting to cross. Without even looking at her Varadin hissed through his teeth, “74!”

The woman looked at him speechless and then quickly looked away, pretending she had not noticed him, as if strictly following the instructions of the famous pocket guide How to avoid troublesome acquaintances. The pedestrian light went green. The traffic had stopped and Varadin Dimitrov crossed the road with long, slow strides like a pair of dividers. The old lady followed him at a careful distance.

The park was full of running dogs and small children. The day wasdry, people from all parts of the world were scattered across the grass, some of them already chewing their lunchtime sandwiches. Varadin Dimitrov took the main path past Kensington Palace – home of the late Princess Diana. Here and there on the railings dangled bouquets of flowers or postcards with messages from the endless stream of the princess’ fans. He walked indifferently around those touching signs of people’s love and stopped for a second in front of the Queen Victoria memorial. It seemed to him that the late Queen bore an astonishing resemblance to one of his relatives who had given him many a drubbing in the past. Then he turned towards the duck pond and followed the water’s edge, sown with bird droppings. He found a free bench and sat down. A goose browsing nearby stretched its neck towards his leg and screeched piercingly.

“55,” he said out loud.

Varadin Dimitrov stayed on the bench for nearly half an hour, without any particular thoughts in his head, gazing at the flat surface of the pond, on which white down floated. The geese and the ducks slowly lost interest in him. Then, totally unexpectedly, he mumbled, “One.”

And smiled, relieved.

The ‘Numerical Therapy’ of Doctor Pepolen was delivering astonishing results. As a man always exposed to nervous stress, Varadin Dimitrov could appreciate that. Doctor Pepolen’s system was based on a few very simple principles. He claimed that human emotions (similar to earthquakes) could be arranged on a scale from 1 to 100, according to their intensity. Registering your emotion – taught Pepolen – is a step towards overcoming it. He conducted specialised workshops, with unstable, easily excited individuals, in which he instructed them in how to measure the level of their emotions. The method comprised the following: when the patient felt he was losing control of his nerves, he had to shout the first number to come into his head, between 1 and 100. After a certain interval, he had to say a further random number, with the proviso that it be smaller than the first. The next time, the number should decrease again. And so on and so forth until the number reached one. At that particular moment, according to Doctor Pepolen, the emotions would be completely conquered, encapsulated and neutralized and the individual would have regained his psychological balance.

Varadin Dimitrov had the pleasure of meeting Dr Pepolen during his mandate in one of the Scandinavian countries. Under the influence of concerned relatives, he enrolled in the famous workshop and for almost three years had been practicing the ‘Numerical Therapy’ method. It works was the only thing he could say. The proof was that he was here now, and not being fried, so to speak, in the consular section of the Embassy in Lusaka. In his line of work, healthy nerves were like ropes for a mountaineer. If the rope does not hold, you fly briefly and then the Sherpas gather up your remains with a dustpan and brush. He had witnessed many such incidents. He had no intention of being one of them. There was only one path – upwards.

Now, when the murky stream of his overflowing emotions had drained away, only pure joy remained in his soul, sparkling like a mountain spring. He had achieved his goal. That moment of surprise. The usual mob that populates embassies the world over had been thrown into turmoil. With indescribable pleasure he imagined the feverish scurrying in the residence. The hysterical phone calls. The panic in the Embassy. They surely expected him to appear at any moment. They were already postponing planned meetings. They were tidying up their desks. He had managed to mess up everybody’s plans.

“Permission to report,” he hissed. “The first stage of Operation Arrival of the Boss, completed with success!”

4

To be, or not to be?

The question repeated itself obsessively in the mind of Second Secretary Kishev as he gazed at the letter on his desk. He dared not open it. The envelope was distinguished by the seal of the Royal Chancellery. The letter had arrived that morning and immediately found itself in his office correspondence drawer. He had no need to open it to guess what was written inside. There were only two possibilities. The first would bury him. The second make him a hero. He was not a gambling type and already cursed himself for taking on this engagement so light-heartedly. This was definitely more than he could handle.

The man who sits quietly by will miss the miracle as it passes, as they say. But how, how could he sit quietly by when his mandate was relentlessly running out; when the days were draining away, one after the other, like the grains of sand through the hourglass? Maybe that was the reason he had grabbed at that straw in the hope of gaining some brownie points and impressing the power-players of the day. He liked life on the Island. He had spent more than two years here and it seemed a cruel injustice to have to pack his bags just now, just when this life had worked its way under his skin. And what was waiting for him back home? That, no one could say. Much water had passed under many bridges during those two years. The government had changed; people he had done favours for and who had supported him had been thrown out of the Ministry; new and hungry people had replaced them and were certain to be making their own arrangements for him. Panicked by the potential results, he had ditched his healthy bureaucratic instinct (he who does nothing makes no mistakes) and thrown himself into feverish activity. He had taken on this delicate mission, which was obviously beyond his capabilities. He had imagined that as a reward they would allow him another mandate in London. Or a year. Even six months would be something! But what could a small Second Secretary do against an Imperial Establishment, centuries old? How could he influence it? From what position? With what means? Nobody would so much as ask. Quite the opposite in fact, they were bound to make him the guilty party – the worm.

You’re out-trumped, Kishev, you’ve out-trumped yourself, he thought to himself, staring gloomily at the envelope. But what if he hadn’t? He should be thinking positively. Positive thinking lies at the heart of every success. Negative thinking is the inheritance of socialism. He carefully opened the envelope and took out the piece of paper with trembling fingers.

Dear Mr. Kishev

Her Majesty thanks you for the kind invitation to attend the cultural festivities organized by your Embassy. Unfortunately, Her

Majesty’s official programme is fully booked and she will be unable to attend.

Yours sincerely,

Muriel Spark

Public Relations Officer.

On behalf of The Palace.

Kishev read the letter another ten times. In both directions. The content remained the same. Then he held the sheet up against the light to examine the watermark. He sniffed it; and he caught that scent of wealth and power given off by objects originating in the world of High Society. Deep metaphysical fear froze his heart.

The bearer of bad news is killed, isn’t he?

At that moment someone knocked at the door. A curly head appeared for a second and then fired the news with the precision of a professional killer.

“The new Ambassador has arrived!”

Varadin Dimitrov turned out to be a very bad psychologist. Contrary to his expectations, the news of his arrival had not hit the Embassy immediately, but had travelled by an overly long and meandering route, following human laws as opposed to nature’s.

Kosta Pastricheff was a lonely and desperate soul, to whom the mere idea of solidarity and mutual aid was foreign. It did not so much as cross his mind to grab the phone and warn his colleagues of their imminent danger. In reality, a cook cannot have colleagues. There is no position in the world lonelier than his. Beneath him there is the assistant-cook. Above him there is God or, according to ones beliefs, an even more frightening Nothing. And Kosta was an atheist.

He served the Mayor a plateful of trotter jelly, opened two ice-cold beers and sat down to keep him company. There was less than two hours left before his flight, but the Mayor was not especially worried: on the contrary, he could not believe that the plane would take off without its most important passenger. They chatted indifferently in the brief pauses between some of the Mayor’s mouthfuls. Kosta had no doubts that the new Ambassador had run directly to the Embassy, and the thought of that made him pull gently at the corners of his greying whiskery moustache. At 15.30 the driver, Miladin, rang the front-doorbell. The Mayor and the cook shook hands.

“If ever you find yourself unemployed,” exclaimed the Mayor, “you are more than welcome in Provadia. With those trotters you’ll not fail, my man!”

The driver, of course, had not the slightest suspicion regarding the dramatic turn of events. He first heard about it from his chatty interlocutor, who did not fail to congratulate him on his new boss. Miladin, who was also a less than outgoing individual of stunted social instincts, decided to keep the news to himself. There was a mobile phone in his pocket, which he deliberately switched off. After he dropped the Mayor at Heathrow, Miladin headed towards one of London’s famed car-boot sales.

Left to his own devices, Kosta dropped the mask of arrogance and indifference, which he always put on in front of other people, and became as gloomy as a peasant watching thunderclouds looming above the harvest fields. He let his wife’s bitching drift past his ears unheeded – she was, as per usual, railing against the social position fate had decreed for her.

“They come here, the dregs of society, stuff their faces, screw everything up, and then guess who gets to clean up after them!” she complained, carrying a stack of dishes to the kitchen. “They all became big-shots! There’s no life left for common folk!”

She was a tiny, thick-set woman with big, workers hands and a bitter mouth. Through eyes that were forever screwed up, she regarded reality around her with mistrust and reproach. As the wife of an international cook, she had ‘done’ a fair chunk of the world, but deep-down she believed that only one patch of her homeland truly mattered – somewhere between the river Iskar and Mount Vitosha. No matter where she stayed – in Paris, Berlin or London – she arranged the family’s way of life according to her pre-Columbian image of the world, slowly reclaiming from the Western jungle a small clearing for her domestic civilization.

Of late, Kosta had frequently asked himself, why the hell had he married her? Or more precisely, why, for fuck’s sake, did he continue to be married to her? Out of laziness, that was the truth of the matter. He had been too lazy to search for the woman of his dreams and instead had opted for the closest one available. He had been too lazy to divorce her afterwards and here they were, already a good twenty years trundling around together. Sex not working. Quarrelling all day. She despised him. He despised her. They had managed two children with a long interval in between. They had some small savings, but too little to be divided up.

After lunch, Chavdar Tolomanov put in a call to the residence. He had been living in London for some years and presented himself sometimes as a salesman, sometimes as a man of the arts, but in reality he made his living some third way, which he avoided ever having to explain. From time to time, Kosta supplied him with cheap cigarettes from the Embassy’s diplomatic quota, and they had gradually become friends. Chavdar had come up with an extremely brash scenario, even judged by the cook’s low standards.

“I wanted to tell you that I’ve pulled a really great chick! Would you believe it? Real Latin American! Do you want her to phone you? Her name is Juliet. It’s just that she doesn’t speak any Bulgarian, ha-ha…”

Loud music was blasting down the earpiece and Kosta concluded that Chavdar was calling from a pub. He was tipsy and obviously having a good time.

“Listen, mate, lets arrange some business…” continued Chavdar. “Is the Mayor gone? Good. Look, I’m making out to this Juliet that I’m the Bulgarian Ambassador. Is it all right if I bring her to the residence? Just for one night, yeah?”

“No way! The new Ambassador’s already arrived.”

“What?!” Chavdar was surprised “How come so suddenly?”

“He dragged his sorry ass in here two hours ago,” the cook replied dryly. “Anyway, I’ve cleaning to be getting on with…” Try making out you’re the Ambassador to me! he thought and slammed down the receiver.

The news, however, had now leaked out. Chavdar Tolomanov did not have the same habits as Embassy people. Without so much as putting down his mobile phone, of which he was inordinately proud, he dialled the first number he came across. At the other end of the line a woman named Dafinka Zaks answered. Zaks lived off her late-husband’s rent and had a reputation as a happy widow. She thirstily soaked up the fresh gossip and delicately declined Chavdar’s proposition that she play the role of the rich, old auntie who lavishly provides space for the intimate adventures of her nephew. Dafinka Zaks shot off the news in several directions and the news spread like wildfire, along the approaches of the entirely unsuspecting Embassy, where the working day was winding towards its natural end.

At 4.30 p.m. the secretary’s telephone rang and an oily voice said, “Could you put me through to the Ambassador, please?”

The secretary, Tania Vandova, flinched as though scalded. She was familiar with that voice and in no way found it congenial.

“The new Ambassador has not yet arrived,” she declared in icy tones.

“Don’t hide him! Don’t hide him!” the voice at other end sang sweetly. “I know from a perfectly well-informed source, that he arrived this very afternoon. I only want to congratulate and welcome him.”

“Your source must have misinformed you,” the secretary attempted a nonchalant tone. “There is nobody here. Goodbye.”

In reality, Tania Vandova was not quite so sure and decided to trust to her well-honed secretarial instincts. A short conversation with the residence followed and Kosta was forced to spit out the truth (a big black mark for the cook!). The news whipped round the offices at the speed of light. At 5.30pm the Embassy emptied as though stricken by the Plague.

5

The eyes of the diplomats were filled with melancholy. They were sat fidgeting around the long empty table in the meeting-room beneath the map of Bulgaria, with its cold pink and yellow colouring. Malicious tongues had it that the map had been put there not so much to arouse patriotic spasms in the employees, but to serve as a reminder of where they came from and where they could be returning if they were not sufficiently careful. In practice, that was the only thing that could truly make them feel anxious. The ghost of going back! This ghost was a constant, inexorable presence around them. It sniggered maliciously in every corner and poisoned their lives with the memory of the finely scented black earth of their birthplace, from the very first to the very last day of their mandates. The subject of ‘going back’ was taboo, shrouded in painful silence. To ask somebody when he thought he might make the return journey (a blatant euphemism) was considered an act of bad taste, base manners and even hostility. Nobody talked about going back, nobody dared to say it out loud for fear of catching the attention of the evil powers that slumbered somewhere deep in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Despite the fact that everyone, down to the last telephonist, knew that this was their irrevocable destiny, as inevitable as winter or death, deep in their hearts they still sheltered the hope that that dolorous hour might pass them by, that they might be missed or forgotten in the overall mass of people and that the awful notice might never reach them. But the notice invariably arrived, along with its sinister title: Permanent Return – the creation of a vengeful bureaucrat from the distant past, the title had remained unchanged throughout the decades. And then began the time of the great retreat, the slow ebb. The condemned soul took to the road, watered with the tears of their predecessors, back to Heathrow Terminal 2, through Gate 7 or 9, and into the gloomy vessel of the national airline ‘Balkan’, after which the door slammed behind their back permanently.

It was soon after 10 p.m. The presidential chair was still empty. At a reasonable distance of a few empty chairs, the diplomats were sat with open pads, pens at the ready. The technical staff had crammed themselves at the other end of the table – the driver, the accountant, the radioman, the cook and the housekeeper. Very few things bonded those people together as did mutual dislike, slowly built up, layer on layer, over the course of all those years of enforced co-existence, resigned to financial and cultural restriction. Nevertheless, it could be said that for some time they had been leading relatively bearable and even carefree lives. They had all had their little pleasures, and they had all had one big, unifying one: they had had no boss. Several months had already passed whilst Sofia dithered over the appointment of a person to this important and sought-after posting. The interests of several lobbies intertwined and hindered one another. So many favours and counter-favours had been called in, so many obstacles found, so many traps laid, that the path to the UK began to look like a cross between an assault course and a mine-field. During that time, while it enjoyed a relative lack of authority, the life of the Embassy reorganized itself independently, on the principles of reason and progress, far from the chaos of administrative orders. The tensions between the employees had eased, some vague spirit of goodwill and mutual aid had been born, which had had a beneficial influence on the actions of the whole collective. Not that the denunciations had stopped entirely, but there was nobody to read them. There was nobody to give red or black marks – Sofia was far removed. But now the bell tolled the end of that calm and natural existence. The boss had arrived. He had arrived suddenly, without prior notice, which made his hostile intentions clear. The life of the diplomats had become messy again.

Shortly, the secretary Tania Vandova came in carrying a big diary-notebook under her arm. “He’s coming,” she said succinctly

Unperturbed, she installed herself in the chair to the right of the presidential seat, opened her pad and also started waiting. Silence reigned supreme in the room.

As he made his way down the stairs, Varadin Dimitrov was imagining the dispirited faces of his underlings and a smile slid across his face. Let them wait, let them tremble! He found no cause to doubt what he had always known: he had in front of him a gang of good-for-nothings, parasites living on the back of the state. At first, their indifference and self-satisfaction amazed him, then made him angry. He started planning ways to poison their existence more efficiently – in order to remind them that this job was not a winning lottery ticket. He liked to observe how they returned to their habitual forms of frightened little beasties. And that was only the beginning.

“Hello to you all,” Varadin greeted them dryly and took his place at the head of the table.

The pens clicked alertly, ready to take note of his immortal instructions. Reflexes die last, he thought happily to himself.

Then, suddenly, he frowned. “Where is Mr. Kishev?”

The diplomats looked at each other and shrugged. The Ambassador shook his head reproachfully.

“I’ll tell you something unpleasant,” he started, as though it was possible that he would announce something different. Long speeches were not to his taste. Speaking frightened him, because it betrayed the chaotic nature of his mind. His thoughts jumped to and fro like grasshoppers that have just crawled out of a closed jar. He found it difficult to gather them back together. For that reason he preferred to open his mouth as little as possible. “In Sofia they think that anarchy reigns here.” Carefully, he gathered the bugs back into his head and continued, “The Embassy is not actively engaged in building Bulgaria’s new image. We are lacking contacts at a high level.”

Silence. Looks, overflowing with devotion.

“As you all know, the European conference opens on Monday,” he continued. “The Prime Minister himself will be participating, along with various members of the Cabinet. It is expected that the EU will announce a new integration strategy. I assume that you are all up to speed on this.”

The diplomats nodded energetically. For just that reason, a dozen faxes had been exchanged between the Embassy and the Ministry. The details of the program had been approved, and speeches and memoranda regarding the intentions of the Cabinet, on any subject, frenziedly translated. The program and the speeches, however, were constantly undergoing some change or other and thus needed to be approved and translated again and again. It was hell on earth, lavishly spiced with hysteria that wafted in clouds from the kitchens of power.

“I am warning you that from now on…” he raised his finger. “I will tolerate no gaffes!”

Gaffes – everyone lived with that nightmare, which often assumed reality. The diplomats were so frightened and overburdened by the system, that they dared not make any independent decisions. The tension often degenerated into apathy, bordering on catatonic stupor at its most decisive. It was at such moments that the nightmares came true.

“What is happening with Mrs. Pezantova’s concert?” asked the Ambassador suddenly, once he was convinced that the previous subject had run its course.

“We are working on it,” called out Counsellor Danailov with the agitated tone of an electrical engineer working on a hopelessly damaged cable. “We are doing everything that’s possible at our end!”

“Then why has it already been postponed twice?” Varadin played the severe inquisitor, narrowing his eyes.

Panic appeared on the faces of the diplomats.

The technical staff observed the inquisition maliciously. Fortunately Tania Vandova was able to explain, “We still cannot ensure a representative from the Palace.”

“Are you inviting them at all?”

“Naturally,” Tania Vandova responded calmly.

Her mandate was coming to an end during the summer, so she did not have much to lose.

“Who is dealing with this?” he enquired coldly.

“Kishev!” they all chorused.

“Does he so much as know that we are here?” asked the Ambassador sharply.

“I don’t know,” shrugged Tania Vandova, “I haven’t seen him since this morning.”

“Go and find him!” he ordered.

This doesn’t look good for Kishev, she thought and quickly left the room.

Oppressive silence reigned.

“The post office workers’ union promised to buy 50 tickets,” the Consul, Mavrodiev, broke in totally inappropriately and at exactly the wrong moment, though probably with the secret hope of gaining the boss’s goodwill.

Big mistake. The Ambassador threw him a look full of hostility.

“As it seems, you are not entirely up to speed!” he spat bitterly, “The idea is not to gather a bunch of riff-raff. We want only the most select audience – aristocrats, world celebrities – the cream of society.”

What am I doing sitting here explaining to this savage?! he said to himself angrily. He imagined Mrs. Pezantova’s address: Dear Ladies and Gentlemen, in front of a crowd of postmen and drivers – unthinkable! It immediately struck him that lying beneath this seemingly well-intentioned proposal lurked a deeper plot: to discredit him in the eyes of those presently in power. From that moment onwards, in his eyes, the good-hearted, clumsy Consul was transformed into Enemy Number One, whose destruction was not to be delayed. With their delicate receptors the others immediately sensed that something bad was happening (danger, danger!) and did not utter another word.

The name of Mrs. Pezantova was a source of worry and agitation for everyone, including Varadin Dimitrov. In fact especially for him. Devorina Pezantova was the wife of an influential Bulgarian politician. She could not possibly accept the secondary role handed to her by history and hungered for her own aura as a woman of social significance. As often happens with such simple folk, lifted suddenly by some twist of fate to the very peak of the social hierarchy, her head was a murky vortex of boundless ambition and grandiose plans. Mrs. Pezantova frantically aimed to join the exclusive club of the world elite, without sparing resources – above all state resources. She dreamed of seeing herself amongst the shiny entourage of celebrities, who filled the chronicles of those fat western publications. In this unequal battle for prestige, Devorina Pezantova had stubborn and ubiquitous opponents – her own compatriots, who inhabited the hopeless space between hunger and darkness. It seemed they could not, or would not, comprehend how important it was that they look good (comme il faut!) at this decisive moment. They failed her at every step and did it energetically too, in a typical Balkan way. Ungrateful tribe! The lady did not give in easily, though. The misery of the masses at large was a good reason for the fine people from all over Europe to gather together, listen to some music, and eat some canapés. Proceeding in the light of that noble logic, she started with great élan to organize charitable events in all those European capitals which sported Bulgarian embassies. This was a heavy task for the missions concerned. The lady was rigorous and was not prepared to acknowledge the limited social effect of her humanitarian activity. She saw treachery, sabotage and conspiracy everywhere. The diplomats were not up to the job and did not take her work to heart; they wanted, more or less, to get the whole thing out of the way and withdraw once more into the swamp of their pitiful existence. Varadin Dimitrov had perspicaciously caught on to her trials and tribulations and managed to persuade her that he was not indifferent to them. For months he was constantly at her side suggesting that he was just the man to bring her dreams to fruition in this Mecca of all snobbery. She had played a more than significant role in his appointment. He owed her.

His gaze slid across the faces of the staff, but it only found downcast eyes. A good sign. He was doing well. A guilty employee was a good employee. Who had said that…?

Carried away by his triumph over those crushed souls, he permitted himself some distraction and his thoughts crawled off in different directions. Dr Pepolen did not have a cure for that ailment. Maybe the only salvation would be to put down poison in all the nooks and crannies of his brain. But there was the risk that the leading thought might die. Which one was it? They were looking frighteningly similar. Which one to choose…?

After a while he said, “The windows are not clean,” with a deep sigh.

The faces of the diplomats showed some relief at the expense of those of the technical staff. Several long, sticky seconds passed. The accountant, Bianca Mashinska, struggled to come up with some sensible explanation, but could not find anything.

Tania Vandova appeared and informed them that Kishev had not come to work at all. She had spoken with his wife: he had heart problems and had been taken into hospital for tests.

Helpless fury overcame the new Ambassador’s heart; he blinked quickly several times and snapped, “You may go!”

6

During that day, many of the employees tried to contact him, but he resolutely refused to see anyone. He wanted to play with their nerves; to leave them with the impression that he knew everything about them and their doings, and that he had no intention of listening to their pitiful explanations. Let them tremble in expectation of his call!

Varadin threw himself into the thorough exploration of the multitudinous drawers and cupboards in his office; the cashbox, the wardrobe and all the other little places where he supposed the spirit of his predecessor might be hiding. Not much was left. People in his profession were secretive and erased all traces behind them, where possible. In the library, the Encyclopaedia Britannica and the ‘Who’s Who’ of 1986 feigned an air of dusty importance. In the draw of the desk lay three lonely paperclips and one used marker. In the safe he found a half-disintegrated washing-up sponge. That looked to be everything. He examined the toilet, tested it and sat behind the big boss’s desk, twisted around this way and that in the armchair to get used to the feel of it. He was almost feeling at home when the red phone rang.

He stared fearfully at it and picked up the receiver.

“Hello!” said a serene female voice. “Already in your workplace, eh? Bravo! Well done!”

“Thank you!” his ingratiating response conveyed little enthusiasm.